|

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE

Appalachian Cultural Resources Workshop Papers |

|

CUMBERLAND HOMESTEADS, A RESETTLEMENT COMMUNITY OF THE DEPRESSION

LIZ STRAW

TENNESSEE HISTORICAL COMMISSION

Cumberland Homesteads Historic District which was listed in the National Register of Historic Places on September 30, 1988, is located in Cumberland County, Tennessee on approximately 10,250 acres near the county seat of Crossville, Tennessee. Built on a plateau of the Cumberland Mountains, the area is primarily rolling hills interspersed by hollows and deep ravines with several small creeks meandering through the colony. Cumberland Homesteads is an unincorporated area but retains a distinct community identity from its plan and the architectural style of the houses and outbuildings.

Cumberland Homesteads was established as a Subsistence Farm Community in 1934 by the Division of Subsistence Homesteads. To better understand the significance of Cumberland Homestead, background on the Subsistence Homestead Program is needed. In May 1933, the National Industrial Recovery Act established the Division of Subsistence Homesteads. The program was aimed at providing housing opportunities for either the under- or unemployed who were willing to work hard to form new communities based on a cooperative form of government and a back-to-the-land philosophy.

On October 14, 1933, the division announced they would concentrate on three types of homestead communities. These included communities for part-time farmers located near industrial employment, communities of resettled farmers from submarginal land, and communities for stranded miners.

The Division of Subsistence Homesteads established thirty-four homestead communities in 1933. Four of the communities, including Cumberland Homesteads, Tennessee, were stranded communities. The stranded communities, composed primarily of miners or timber workers who had been in and out of work since the 1920s, were the most controversial of the homestead communities. The communities brought about several protests from opponents of the "back-to-the-land" movement who did not believe that the communities would ever support themselves because they were located in rural areas where little or no job opportunities existed for the homesteaders.

The stranded communities represented the continuation of the relief work started by the American Friends Service Committee in the mining areas of West Virginia, Maryland, Kentucky, Tennessee, Illinois, and Pennsylvania. The American Friend's Service Committee provided relief for an estimated five hundred thousand unemployed or stranded workers with assistance from the Federal Council of Churches, U.S. Bureau of Education, and the Pennsylvania Bureau of Education. Assistant Director of the Division of Subsistence Homesteads, Clarence E. Pickett, had been the director of the American Friends Service Committee. Pickett's work, which included subsistence farms, part-time farms, part-time mining, garden clubs, and handicraft shops, had been admired by Eleanor Roosevelt. Mrs. Roosevelt's interest and support of Pickett's work probably guaranteed the subsistence homestead program additional support from the Administration.

The Subsistence Homesteading Program was based heavily on agrarian reverence for the land, the "back-to-the-land" philosophy and on the premise that rural living was healthier than city living for the country's poor, a premise that Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt both strongly endorsed. The Subsistence Homestead Program was meant to serve as a temporary relief measure and represent a return to the "simpler and healthier" agrarian past the country once knew. The premise behind the homestead villages was to provide families with the means to raise their own vegetables, chickens, cows, or hogs to supplement their income while working at other jobs. In addition to the subsistence farming, emphasis was placed on community cooperation and socialization, based on earlier communal living movements by the Shakers and the Amana Inspirationists. Homesteaders were expected to work for the good of the community as well as for their own families. The government supported and encouraged adult education and women's clubs. The goal was to educate the stranded families to a better and healthier way of life. In addition to developing homemaking skills, the women were strongly encouraged to work with crafts, especially weaving, as a method of providing additional support for their families. The majority of homesteads were intended, from the beginning, to be only part-time farms with outside employment as an essential part of the program.

|

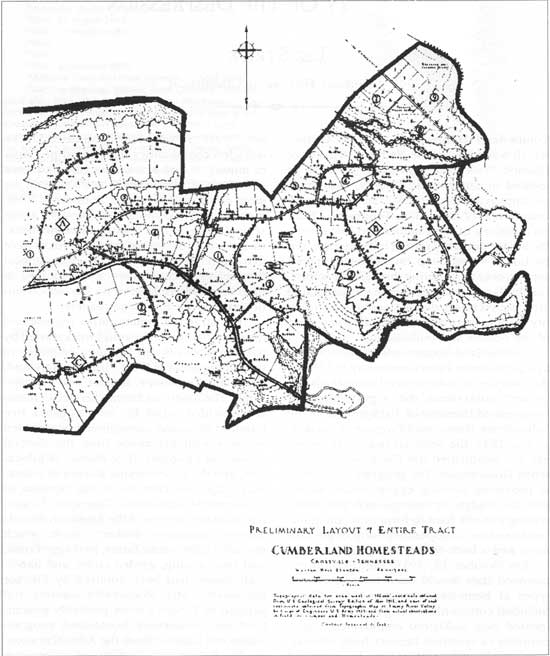

| Detail from William Stantion's Cumberland Homesteads map. |

The Division of Subsistence Homesteads was one of Roosevelt's numerous "alphabet agencies" that were challenged in the courts. As a result of its temporary status as part of the National Industrial Recovery Act, it was ruled that the Division of Subsistence Homesteads would expire on June 15, 1935. However, before its expiration, executive Order 7041, issued on May 15, 1935, transferred the homesteads program to the Resettlement Administration. In turn, in 1937 the Bankhead-Jones Farm Tenant Act, placed the Resettlement Administration (and the Homestead Communities) under the Farm Security Administration.

Cumberland Homesteads as a planned community is a nationally significant representative of this important, although relatively small, relief program under the New Deal. Of the twenty-five million dollars allotted for the Subsistence Homestead Program, $825,000 was earmarked for Cumberland Homesteads. In 1934 the Division of Subsistence Homesteads purchased 11,600 acres in Cumberland County from the Missouri Coal and Land Company. Of the 11,600 acres, 4,200 acres were to be left in forest to provide timber and firewood to the homesteaders. The original plan for the homesteads called for 350 farms to be built on tracts from four to thirty-five acres. Over twenty-five hundred applications were received for the planned 350 homesteads. Applicants from Cumberland County and the surrounding counties of Fentress, Putnam, and Morgan were carefully screened by government workers for abilities, desire to work, age, etc. The average homesteaders was thirty-four years old and married with three children.

Relief workers from the Civil Works Administration (CWA) did much of the initial clearing of the tract and some of the early construction on the homestead project. Some of the early CWA workers were later accepted as homesteaders. Most of the houses built in the Cumberland Homesteads were completed under a "self-help" program with the homesteaders being paid to build their own houses and outbuildings.

In 1934 twenty barns were completed and occupied by homesteaders, including ten families. Homesteaders first moved into "communal barns" until a "family barn" was completed. Upon completion of the "family barn" the homesteader's family moved into the barn while construction on their house progressed. By June 1934, two of the houses were completed and eight were under construction. In addition a planing mill was in operation, a dry kiln was being constructed, and 115 homesteaders were at work on the homestead project.

Both the plan and the buildings of Cumberland Homesteads were designed by architect, William Macy Stanton, who came to Cumberland Homesteads from Norris, Tennessee, a TVA-planned community where he had designed the houses. Stanton was responsible for the initial design involving street layout, location of the community center, and the design of all residences and outbuildings in Cumberland Homesteads.

|

| View of a sandstone faced house at Pigeon Ridge, architect William M. Stanton |

|

| View of homestead landscape, Cumberland Homesteads Historic District |

Homesteads were built on lots averaging from ten to 160 acres with the average homestead consisting of sixteen acres. Areas that were determined unsuitable for farming were left as timberland. Originally 8,903 acres were farm tracts, 1,245 acres were common land (grazing, woodland, cooperative enterprises), 11,200 acres were held for further development, and 5,055 were owned by the cooperative association. In 1938 land held by the government and by the cooperative association for Cumberland Homesteads totaled 27,802 acres.

There are approximately fifteen different house designs in Cumberland Homesteads, eleven of which are repeated. The other four houses were one-of-a-kind houses. All houses have indigenous Crab Orchard sandstone exteriors with wood paneled interiors. The materials for the construction of the houses came from the immediate area. The sandstone was quarried within the boundaries of the homestead community, and all lumber was cut and processed on the grounds. All houses were built with plumbing and wiring. Electricity was supplied to the homesteads by TVA in December 1937.

Houses were generally one to one and a half stories with sandstone walls and gable roofs. The Crab Orchard sandstone walls were constructed with either quarried stone or field stone. All houses originally had open shed roof entrance porches, some of which have been enclosed. Homeowners were allowed to make minor changes to the stock plans and several houses were built with reversed plans, different orientation to the road and variations to interior room design. Generally the houses were four to seven rooms, contain one or two fireplaces, and had paneled walls, built-in bookcases, and batten doors with "Z" braces and hardware made by the community blacksmith shop. The wood used in the construction of the houses was harvested from land immediately surrounding the homestead. The majority of the interior walls and woodwork in the houses were of white or yellow pine, with some poplar and oak.

A variety of outbuildings were constructed for each Farm Homestead. Outbuildings include barns, shed, chicken houses, smokehouses, root cellars and privies. Generally these outbuildings were placed in a standard pattern behind the houses. Also constructed were some larger commercial size poultry houses for the cooperative enterprise.

In addition to the Farm Homesteads, a number of community buildings were constructed as part of the original Cumberland Homesteads. At the intersection of Valley Road (or U.S. Highway 127) and Grassy Cove Road (or State Route 68) near the center of the project on a parcel of land set aside for the community center, is the Cumberland Homesteads Tower, an eight-story tall structure built to house the water tank with a cruciform base containing offices and meeting rooms. Built directly behind the Tower are the original Homestead Schools, both elementary and high school buildings. Built in a unique pod style, the schools have individual classrooms that are freestanding, but are connected by covered walkways. The high school also has two separate structures, a home economic lab and a craft building.

Also located near the center of the project is Cumberland Mountain State Park, a CCC project built in conjunction with the Homesteads. The park is approximately 1,300 acres, consists primarily of timberland and Byrd Lake, a man-made lake. Along with the large masonry arch dam to contain the waters of Byrd Creek, the CCC constructed cabins, a beach, bathhouse, boathouse, and two hiking trails.

Several cooperative buildings were also constructed in the community. Cooperative buildings included two factories (a canning factory and a hosiery mill), a cooperative store, a government garage, and a loom house. The loom house now serves as a back room to a church. Along with the loom house, the hosiery mill, garage, and the water towers for the cannery and hosiery mill are extant. However, all extant cooperative buildings, except for the water towers, have undergone major alterations and no longer contribute to the district.

A celebration was held on July 28, 1939, to mark the completion of Cumberland Homesteads although only 251 of the originally planned 350 houses were built. In 1939 the government began the transfer ownership of homes to the homesteaders who had been renting. The federal government left the community in 1947 with the house transfers completed and the donation of the twenty-seven acres of land that contained the administration building, waterworks, and schools to the county.

The landscape features of the community have remained relatively unchanged. Originally timberland cleared by homesteaders and CWA workers, the majority of the community still remains as open farm land with only minor changes to the road patterns, the farm fields, and timberland. The large homestead tract was designed around some of the existing roads and highways with new roads and bridges added in 1934 to facilitate travel through the area. Groups of farms and their fields were separated by wire fences. Many of these back fence lines and fences are still extant.

Landscaping of individual yards appears to have been a part of the overall planned design. Daily reports submitted to the Division Office in Richmond report that during the first year the hilly portions of the yards were seeded with grass, in some instances blue grass and clover. The daily reports also mentioned that two thousand raspberry plants were set out at Grassy Cove. Remnants of a fruit orchard are still visible from Highland Road. The daily reports from 1934 indicate that some form of plan was used for landscaping the individual farmsteads, but no specific plans have been located.

Other landscape features include the original Crab Orchard sandstone and sand quarry sites as well as the original cemetery. The cemetery, not included in the original plan was hastily laid out upon the death of an original homesteader's young daughter. The cemetery appears to have been used for only a short period of time and is now overgrown and inaccessible.

Modern subdivisions have been constructed within the boundaries of the community, which has included the addition of new roads. Areas of new development within the boundaries are highlighted in yellow. Most changes have occurred in areas that were originally undeveloped, or on the main roads in the community and at the outer boundaries of the area. Am this time the amount of development does not detract from the original plan of the Cumberland Homesteads Historic District. Many of the new houses built in the homestead community are interspersed between farmsteads.

However, while this development currently does not detract from the original plan of the district, the threat of additional development may have a major impact on the historic district. In 1989 Cumberland County was the fastest growing rural county in the state. In 1989 there was a 16.6 percent increase in population, or approximately an additional five thousand people from 1980. Preliminary figures from the 1990 census show the county population has continued to grow although at a slower rate than earlier figures indicated. One of the reasons for the county's rapid growth has to do with the fact that Crossville and Cumberland County have been named number four in the United States for retirement living by Rand McNally magazine. As a result, there are six growing retirement resort areas, one of which threatens the district, along with development of additional subdivisions on the southwest side. In fact, a recent call to a staff member in our office has indicated that additional subdivisions are planned for some of the open land located within the district.

While much of Cumberland Homesteads still retains it community identity through its open rural landscape and has had a interested historical group, there are no plans for any form of historical zoning to protect the community. As such, it provides an example of the problems faced by many of the rural districts and planned communities in Tennessee.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

appalachian/sec8.htm

Last Updated: 30-Sep-2008