|

Bent's Old Fort National Historic Site Colorado |

|

NPS photo | |

At a distance it presents a handsome appearance, being castle-like with towers at its angles ... the design ... answering all purposes of protection, defense, and as a residence.

—George R. Gibson, a sold1er who visited the fort in 1846

In the decades after the 1803 Louisiana Purchase, even as the earliest explorers crossed the continent, America's economic frontier expanded westward. Trappers went into the Rockies for beaver, Plains Indians showed their willingness to trade buffalo robes, and the first wagons rolled between the Missouri River and Santa Fe, initiating regular commerce with Mexico. When traders Charles and William Bent and their partner Ceran St. Vrain sought to establish a base, they wanted to locate where they could take advantage of all these trades. In 1833 they built a fort (then called Fort William) on the north bank of the Arkansas River, the boundary between the United States and Mexico. It was close enough to the Rockies to draw trappers; near the hunting grounds of Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa, and other tribes; and on the Santa Fe Trail, near a ford across the river.

The fort was not the only sign of human life in the area—the high plains had long been home to thousands of Indians. But for travelers two months on the trail, it was a greatly anticipated haven, the sole place between Independence and Santa Fe where they could refresh themselves and their livestock, repair wagons, and replenish supplies.

The Bents' Mexican trade grew rapidly as their caravans plied the route from Independence and Westport to company stores in Santa Fe and Taos. There, goods like cloth, hardware, glass, and tobacco were exchanged for silver, furs, horses, and mules. Thousands of beaver pelts passed through the fort in the early years, but as the market for beaver declined in the 1830s, the Indian trade became a business mainstay. The fort's traders swapped American and Navajo blankets, axes, firearms, and other items for buffalo hides and horses taken in raids—no questions asked. The Bents' reputation made their traders welcome in most villages and drew growing numbers of Indians to the fort. Before long the company dominated the Indian trade on the southern plains. So effective as peacemakers were the Bents, especially with the Southern Cheyenne, that in 1846 the fort (by then called Bent's Fort) was used as headquarters for the Upper Platte and Arkansas Indian Agency.

That year military operations stepped up the pace of activity beyond that of the seasonal trade. America was going to war with Mexico, and the fort's strategic location on an established road made it the ideal staging point for the invasion of Mexico's northern province. Storerooms were filled with military supplies; soldiers were quartered at the fort; military livestock stripped the land. Later, a growing stream of settlers and gold-seekers disrupted the carefully nurtured Indian trade. In the face of polluted water holes, decimated cottonwood groves, and declining bison, the Cheyenne moved away. Escalating tensions between Indians and whites and a cholera epidemic finally killed the trade. After the death of Charles in 1847, St. Vrain tried unsuccessfully to sell the fort to the U.S. Army. It is thought that William Bent tried to burn the fort in 1849 before moving to his trading houses at Big Timbers, 40 miles downriver. He constructed Bent's New Fort there in 1853.

Bent's Old Fort was an instrument of Manifest Destiny and a catalyst for change. The company's influence with the Plains Indians and its political and social connections in Santa Fe helped pave the way for the occupation of the West and the annexation of Mexico's northern province. Its trade with the Indians introduced a level of technology that, for better and worse, irrevocably altered their culture. And the fort's immediate effects on the land and water were signs of wider environmental change to come.

Bent, St. Vrain & Company

Charles and William Bent, sons of a St. Louis judge, were drawn to the Upper Missouri fur trade as young men. Sensing greater opportunities in the Arkansas Valley, they led a caravan to Santa Fe in 1829. A year later they formed Bent, St. Vrain & Company with Ceran St. Vrain, ex-trapper and Taos trader. Charles directed the Santa Fe trade, living in Taos and taking seasonal trips back to St. Louis. He married into a prominent Taos family and used his influence to smooth the way for American trade. Shortly after being named Provisional Governor of New Mexico in 1846, Charles was killed in Taos during an uprising of Pueblo Indians and New Mexicans. William directed the Indian and trapping trade at the fort. He often lived with his Cheyenne wife Owl Woman in her village, where he was known as Little White Man. William was largely responsible for the company's excellent reputation among the Indians. St. Vrain ran the company's stores in Taos and Santa Fe. Like Charles he became a man of some importance in New Mexico, serving as American consul in Santa Fe in the 1830s.

Refuge on the High Plains

As a center of trade and an oasis in the Great American Desert, Bent's Fort was a magnet for the adventurous, scholarly, and the curious. Explorers, travelers, and journalists stopped here to observe the varied commerce and diverse cultures. The fort's known hospitality and the chance to meet mountain men and guides like Kit Carson and Thomas Fitzpatrick also drew travelers. One of the most articulate was George Ruxton, an English writer and ex-soldier who wrote of the fort's "leather-clad mountaineers" gambling away their pelts; of Indians wrapped in buffalo robes leaning against the outside walls; and of the fort's "striking appearance ... on the vast and lifeless prairie." Adolph Wislizenus, a German-born doctor who left his practice in Illinois to see the Rocky Mountains, called the fort the "finest and largest ... we have seen on this journey." Wislizenus knew the "character of the country" could not endure, foreseeing the time when the "present narratives of mountain life may sound like fairy tales."

A military presence at the fort became a fact of life in its last years. We owe much of our knowledge of its appearance to Lt. James W. Abert, a young topographical engineer. In two stays at the fort in 1845 and 1846, he made many sketches of the structure and of the Indians who came here to trade. Abert accompanied two of the fort's most famous visitors: Gen. Stephen Watts Kearny, who used the fort as an advance base for his invasion of New Mexico, and the explorer John Charles Frêmont. Frêmont once wrote of being greeted at the post with "repeated discharges from the guns of the fort." Gen. Henry Dodge stopped here in 1835 to organize a peace council between friendly Cheyenne and Arapaho and their old enemies, the Pawnee. This was the first of several intertribal councils at the fort. Because the Bents had won the confidence of the warring tribes, they were willing to sit down together at the fort to discuss peace. The Bents, of course, had a vested interest in these talks, knowing that a stable trading environment was good for business. The Cheyenne especially were frequent visitors. They often moved entire villages to the Arkansas River area because of the fort. The Bents had gained their trust by seeking out their villages, offering plentiful trade goods, and trying to keep alcohol out of the trade. William's marriage to Owl Woman helped cement good relations with the Cheyenne tribe.

Touring Bent's Old Fort

It is crowded with all kinds of persons: citizens, soldiers, traders to Santa Fe, Indians, Negroes, etc. The Indians were Arapaho, a fine-looking set of men, with mules to trade.

—George R. Gibson, account from his 1846 journal

Bent's Fort during the Fall trade season: The caravan from Independence has unloaded part of its goods before moving on to Santa Fe, and the fort population, normally 40 to 60 employees, swells with people drawn by the new merchandise. The place is a babel of tongues: English, Spanish, French, and two or three Indian languages. The buffalo hunt has begun, and the Indians are already bringing in tanned robes that will be baled in the fur press. Many are familiar figures, especially those who are wives of traders and trappers. The Cheyenne and Arapaho, on good terms with the Bents, are no longer required to use the trading window outside the fort's massive doors; they are allowed to enter the fort.

Company traders are packing their goods, preparing to move out into the Indian villages. Although the beaver trade has been declining, a few diehard French-Canadian and American trappers, freshly provisioned at the fort, are ready to head for the mountains.

Some, like Kit Carson, have abandoned the trade to become guides and hunters, supplying the fort with buffalo meat. In the corral, black and Mexican teamsters wrestle with unruly mules and oxen, while others break wild horses brought in by Plains Indians and parties of Americans.

Life at a Cultural Crossroads

When Bent, St. Vrain & Company planned a new trading fort in a region with limited timber, the traders turned to adobe, a building material long favored by Mexicans. Clay, water, and sand, with straw or wool as binders, were mixed in pits, formed into 18" by 9" by 4" bricks, and dried in the sun. Although Mexican laborers, usually women, had to regularly maintain the adobe plaster, the bricks proved reasonably durable in the dry climate.

What you see today is a reconstruction of Bent's Old Fort, built with similar materials and furnished mostly with reproductions. Because researchers relied on detailed drawings of the fort by visitors, contemporary descriptions, and archeological findings, the appearance is close to that of the original. The most valuable of the drawings were those done by Lt. James Abert in 1846.

The no-nonsense appearance befitting the fort's commercial function gave little indication of its role as a cultural crossroads. It was a stopping place for travelers from the East, an employer of Mexican laborers, a rest and relaxation site for trappers and hunters, and a neutral ground for Indian peace councils.

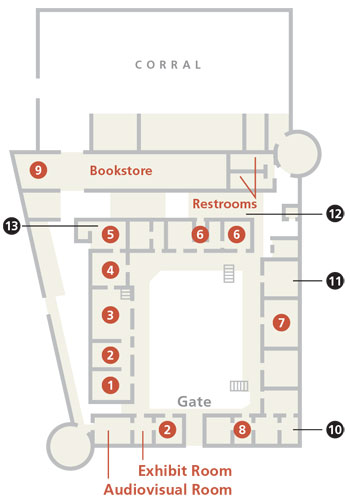

(click for larger map) |

Though the functions of some of the rooms reflect cultural and ethnic barriers, others were places where the groups could work and trade in relative harmony. By the 1840s, when the Cheyenne and Arapaho had open access to the fort, the trade rooms (2) were places where all intermixed freely. Here Mexicans, Indians, and trappers could trade their furs and hides for goods ranging from blankets, cloth, iron wares, and powder to luxuries such as coffee, tobacco, brass rings and bracelets, and beads. Sometimes the terms of trade were agreed upon in the council room (1), also used as a parlor and for peace talks between warring tribes.

Other community focal points were the blacksmith's and carpenter's shops (6). The blacksmiths and carpenters who worked and lived here were typically American traders from the East.

The casual attitudes that led to occasional intermarriage and easy mixing of groups in the workplace and at fandangos (dances) did not apply to all social relations. The dining room (3), the largest room in the fort, was used by the owners and their guests, including some traders, trappers, and hunters. Everyone else cooked in their quarters or ate from a community cooking pot.

One visitor marveled at the "regularly established billiard room (12)." In 1846 a Cheyenne named Bear Above posed for Lieutenant Abert, "seated upon the billiard table," but normally the drinking and gambling there did not include Indians or Mexican laborers.

Furs and barrels, boxes, and sacks of trade goods were stored in the warehouses (7) in the winter. Throughout the 1840s these rooms, which contained underground pits, were also used for temporary storage of military supplies.

At nightfall the social distinctions were most apparent: The owners had their own quarters, craftsmen ate and slept where they worked; Indians slept outside the fort; and trappers and hunters lived and ate together in the trappers' and hunters' quarters (11). Free trappers stayed only long enough to trade their goods and sample civilized life, while the company hunters remained in the area supplying the fort with buffalo meat and venison.

Mexican laborers from Santa Fe and Taos—those who built and maintained the fort—had their own rooms in the laborers' quarters (8) on the ground level. Mexican women also cooked for their families and helped the head cook prepare meals for the owners and guests.

The cook was a slave, Charlotte, brought from St. Louis along with her husband Dick and his brother Andrew. She lived in the cook's room (4) between the dining room and the kitchen (5). From here she could quickly supply food and drink while overseeing other domestic chores. The few white women visiting the fort enjoyed the best accommodations. Susan Magoffin's quarters (10) may normally have been used by the fort's resident physician. Magoffin, the wife of a prosperous trader, had a miscarriage and was confined to her room throughout her 12-day stay at the fort.

Visiting the Park

The National Park Service provides tours, programs, a short film, and other interpretive activities to help you understand Bent's Old Fort. Call for summer and winter visiting hours. Organized groups who want tours of the fort should call for reservations.

You can buy an entry pass and see exhibits at the information kiosk near the parking lot. There is a short walk to the fort. Transportation is provided for those who need assistance. The nonprofit Western National Parks Association sells books, postcards, and historical reproductions inside the fort.

For Your Safety

Beware of possible hazards. Watch your footing, and keep off walls Maintain a

safe distance from animals. Pets must be on a leash and are not allowed to enter

fort rooms. Report safety hazards or emergencies to park rangers.

Getting Here

The park is eight miles east of La Junta and 15 miles west of Las Animas on

Colo. 194. Buses serve both towns; Amtrak serves La Junta.

Source: NPS Brochure (2007)

|

Establishment Bent's Old Fort National Historic Site — June 3, 1960 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

1976 Archeological Investigations, Trash Dump Excavations, Area Surveys, and Monitoring of Fort Construction and Landscape: Bent's Old Fort National Historic Site, Colorado (Douglas C. Comer, June 1985)

Bent, St. Vrain & Co. among the Comanche and Kiowa (Janet Lecompte, The Colorado Magazine, Vol. 49 No. 4, Fall 1972)

"Bent's First Stockade — 1824-1826" (Charles W. Hurd, extract from The Denver Westerners Monthly Roundup, Vol.16 No. 4, April 1960; ©Denver Posse of Westerners, all rights reserved)

Bent's Fort: An Outpost for Cultural Exchange and Exploration of the West (Emma Perkins, c2017)

Bent's Fort: An Outpost for Cultural Exchange and Exploration of the West (Emma Perkins, extract from The Denver Westerners Roundup, Vol. 73 No. 1, January-February 2017; ©Denver Posse of Westerners, all rights reserved)

Bent's Fort in 1846 (Edgeley W. Todd, The Colorado Magazine, Vol. 34 No. 3, July 1957)

Bent's Old Fort (The Colorado Magazine, Vol. 54 No. 4, Fall 1977)

Life in an Adobe Castle, 1833-1849 (Enid Thompson)

From Trading Post to Melted Adobe, 1849-1920 (Louisa Ward Arps)

From Ruin to Reconstruction, 1920-1976 (Merrill J. Mattes)

The Architectural Challenge (George A. Thorson)

Furnishing a Frontier Outpost (Sarah M. Olson)

Bent's Old Fort: An Archeological Study (Jackson W. Moore, Jr., 1973)

Bent's Old Fort and Its Builders (George Bird Grinnell, Kansas State Historical Society, Vol. 15, 1923)

Bent's Old Fort National Historic Site Junior Ranger Guide (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Clean Water Act Water Quality Designated Uses and Impairments for Bent's Old Fort National Historic Site NPS Technical Report NPS/NRWRD/NRTR-2003/302 (March 2003)

Cultural Resource Management Plan, Bent's Old Fort National Historic Site (Susan A. Tenney, 1984)

Family Self-Guide Activity Book, Bent's Old Fort National Historic Site (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Foundation Document, Bent's Old Fort National Historic Site, Colorado (September 2013)

Furnishing Plan for Bent's Old Fort National Historic Site (Sarah Olson, 1974)

Furnishing & Exhibition Data Section, Bent's Old Fort National Historic Site (Nan V. Carson, undated)

Furs and Forts of the Rocky Mountain West (Arthur J. Fynn, The Colorado Magazine, Vol. 8 No. 6, November 1931 and Vol. 9 No. 2, March 1932)

Gathering War Clouds: George Bent's Memories of 1864 (Steven C. Haack, extract from Kansas History: The Journal of the Central Plains, Vol. 34 No. 2, Summer 2011)

Geologic Resource Evaluation Report, Bent's Old Fort National Historic Site NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2005/005 (K. KellerLynn, September 2005)

Geophysical Survey of Archaeological Site, Bent's Old Fort National Historic Site, Otero County, Colorado (Lewis E. Somers, March 1996)

Historic Furnishings Study, Bent's Old Fort National Historic Site, Colorado Draft (Enid T. Thompson and Sarah Olson, March 1974)

Historic Structures Report, Part I: Historic Reconstruction, Bent's Old Fort, La Junta, Colorado (Dwight E. Stinson, Jr., Jackson W. Moore, Jr., and Charles S. Pope, 1965)

Historic Structures Report, Part II: Reconstruction of Bent's Old Fort, Bent's Old Fort National Historic Site (Dwight E. Stinson, Jr. and Jackson W. Moore, Jr., June 1965)

Letters and Notes From or About Bent's Fort, 1844-45 (Copied from the St. Louis Reveille, The Colorado Magazine, Vol. 11 No. 6, November 1934)

Master Plan, Interpretive Prospectus, Development Concept, Bent's Old Fort National Historic Site, Colorado Draft (March 1975)

Master Plan, Interpretive Prospectus, Development Concept, Bent's Old Fort National Historic Site, Colorado Final (November 1975)

More About Bent's Old Fort (The Colorado Magazine, Vol. 34 No. 2, April 1957)

Meanderings of the Arkansas River Since 1833 Near Bent's Old Fort, Colorado USGS Professional Paper 700-B (Frank A. Swenson, 1970)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Bent's Old Fort National Historic Site (Carl McWilliams and Karen Johnson, April 20, 1984)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Bent's Old Fort National Historic Site NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SOPN/NRR-2015/998 (Kimberly Struthers, Robert E. Bennetts, Patricia Valentine-Darby, Nina Chambers and Tomye Folts-Zettner, July 2015)

Newsletter (Bent's Fort Ledger): Fall 2007 • Winter 2007 • Fall 2008 • Winter 2008 • Fall/Winter 2010

Sidelights on Bent's Old Fort (Arthur Woodward, extract from The Colorado Magazine, Vol. 33 No. 4, October 1956)

Statement for Management — Bent's Old Fort (September 1990)

The Chaos of Conquest: The Bents and the Problems of American Expansion, 1846-1849 (David Beyreis, extract from Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains, Vol. 41 No. 2, Summer 2018)

The Excavation of Bent's Fort, Otero County, Colorado (Herbert W. Dick, The Colorado Magazine, Vol. 33 No. 3, July 1956)

The Ladies of Bent's Fort (Enid T. Thompson, extract from The Denver Westerners Roundup, Vol. 30 No. 9, November-December 1974; ©Denver Posse of Westerners, all rights reserved)

When Was Bent's Fort Built? (LeRoy R. Hafen, The Colorado Magazine, Vol. 31 No. 2, April 1954)

beol/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025