|

Big Bend

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 13:

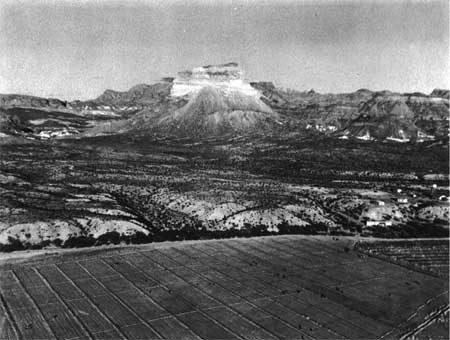

A Park at Last: Land Acquisition, Facilities Development, And Border Issues in Big Bend, 1940-1944

For promoters of Texas's first unit of the National Park Service, the dream of the 1930s came true when the state legislature agreed in 1941 to purchase the land identified for Big Bend National Park. A concentrated twelve-month campaign of survey and acquisition included reestablishment of the abandoned Civilian Conservation Corps facility in the Chisos Basin, this time to construct buildings for visitor services and administrative use. Park officials also continued their efforts to link Big Bend with Mexico, even though the press of the Second World War limited planning and implementation of the hopes of FDR and Lazaro Cardenas for a realization of the "Good Neighbor" policy. Finally, the NPS selected a staff in anticipation of the first visitors to southern Brewster County, with Ross Maxwell designated as the inaugural superintendent of the Lone Star State's "crown jewel" on the Rio Grande.

Changes in the political landscape of Austin in the winter of 1941 inspired Big Bend advocates. On January 23, Fort Stockton senator H.L. Winfield introduced Senate Bill 128, a measure to allocate $1.5 million from the state general fund to purchase land for the park. Soon thereafter, Eagle Pass state representative Calvin C. Huffman joined sixteen colleagues to introduce House Bill 63 for the same purpose. Local promoters then invited members of the state senate's appropriations committee to tour the future park site, with Frank D. Quinn, executive secretary of the Texas state parks board, Everett Townsend, and NPS representatives John C. Diggs and Ross Maxwell as guides. Then on March 5, 1941, regional director Minor Tillotson appeared before the appropriations panel to champion SB 128. Two months later, the Big Bend Park Association petitioned Amon Carter to form an eleven-member executive committee to promote the bill. Carter's decision not to release monies from the association's account for publicity led the Alpine chamber of commerce to undertake a frantic campaign to collect funds for this purpose, leading James Casner of Alpine to recall years later that this saved Big Bend. [1]

By June of that year, Winfield and Huffman had shepherded the Big Bend land-acquisition bill through the halls of the Austin legislature, achieving on June 17 the victory so long sought by west Texas park promoters. Two weeks later, Governor W. Lee O'Daniel signed into law the General Departmental Bill that included Big Bend's $1.5 million. Winfield recalled how delicate the negotiations and voting had been, and how the governor still had doubts about the wisdom of such an appropriation. The Fort Stockton lawmaker went to O'Daniel's office after passage of the measure to obtain his signature. James Anderson would write in 1965 that Winfield "told O'Daniel that he could not let him down, and tears streamed from Winfield's eyes as he pleaded for the park." Speaking with James Casner two decades after the creation of Big Bend, Anderson would note that "Casner believed that 'without Winfield, we would have never had a park,' because if O'Daniel had vetoed the bill, it would have died." [2]

No sooner had the governor approved of the bill than did opponents of excessive public spending initiate action to stop the land-acquisition process. State representative A.H. King of Throckmorton filed an injunction against the state comptroller, George H. Shepperd, prohibiting him from releasing any funds for Big Bend. This maneuver endangered the success of the campaign, in that the bill had given the state parks board only twelve months to complete all transactions. While NPS and state officials engaged in preliminary studies of land titles and conducted evaluation surveys, the Texas court system held the project in check until the state supreme court on February 4, 1942, denied King's appeal. Thus the appraisal team of Frank D. Quinn, Everett Townsend (associate administrator), Eugene "Shorty" Thompson (chief appraiser), A.T. Barrett (junior assistant appraiser), Robert L. Cartledge (auditor), and Frederick Isley (assistant attorney general), among others, could move forward with the massive task of securing the consent of over 5,000 landowners, the vast majority of whom lived out of state and owned less than ten acres each. [3]

With Thompson handling the negotiations, and Townsend serving as the liaison with local politicians, the Big Bend Land Department devoted the months of September through November to a complete survey of the southern portion of Brewster County. They agreed that 99 percent of the future park should be classified as grazing land, calculating payment on such features as the extent of grazing, proximity to water, lease agreements, and the value of improvements on the land. Office staff in Alpine prepared long lists of landowners, with their acreage, value, and taxation noted for use by Thompson and his surveyors. The staff also detailed the public school lands, with their mineral rights. They determined that some 2,353 individuals would be approached for sale of 1,154 sections of land (a total of 777,718.18 acres). With administrative costs included, Thompson and his colleagues believed that they could fulfill the legislature's mandate by August 1942 with expenditure of $1,486,315.24. [4]

As the surveyors fanned out across Brewster County, NPS officials reviewed the documentation needed to insure federal control of the land. On October 8, 1941, acting Interior secretary E.K. Burlew approved a clause in the draft agreement with the state of Texas stating that the federal government would give any purchased land back to the Lone Star state if Big Bend should ever cease operations. Soon thereafter, the Big Bend Land Department announced that it had inventoried nearly 5,000 parcels, with closure on the survey process targeted for November. In early December, Eugene Thompson and his staff outlined the procedure for payment. One dollar per acre would be offered for land considered "very poor," which James Anderson in 1965 called "the semi-rolling, eroded area with little feed and top soil." Adding to the modest value of this land, said Anderson, were the presence of "grave and greasewood, some areas of water retention, hills, and fair grazing." Next in value were lands considered "poor," and for which the state would pay $1.50 per acre. These Anderson defined as "accessible to distant water," and which had "some hillside grazing." Acreage worth $2.00 apiece the land department described as "areas which had fair grazing, access to a spring or tank, rolling topography, and fair top soil and more moisture." The best land that would fetch in excess of two dollars per acre included the Chisos Mountains, "where there was good year-round grazing." [5]

When the state parks board and Big Bend land department met on December 8 with officials of the NPS, the outline of purchasing had become clear. The largest landowner by far was the Texas and Pacific Railway, which held 41,500 acres (the equivalent of nearly 65 square miles). Three parcels ranged between 20,000 and 30,000 acres, with Homer Wilson's ranch in the Chisos Mountains at 28,804 acres, and Wayne R. Cartledge's 20,650 acres near Castolon among them. Twelve additional ranches had between 10,000 and 20,000 acres, while the remaining owners had modest to miniscule holdings in the future park area. Land department officials then told the park service and state parks board that the King case hampered their ability to make offers on these parcels, and that reluctant owners might require the application of condemnation procedures (something that the federal government had never done before in Brewster County). Finally, the surveyors were surprised to learn that, in the words of James Anderson, "much curative title work would be necessary because of the 'almost total' absence of abstracts from most of the owners." The state and federal officials thus approved the use of title insurance to expedite the search process, and also agreed to grant grazing permits of up to three years' duration to existing ranchers in exchange for their promises of sale. [6]

Armed with these gestures of support, Eugene Thompson and his staff drew boundary lines that conformed to the parcels defined in their surveys. With the exception of the Rio Grande, the land department preferred following section lines to simplify mapping. The NPS wanted "a land of contrasts," wrote Anderson, and thus reviewed the land department's maps to accommodate that concept. Ross Maxwell, even though he spent the year 1942 working as assistant superintendent of the Southwestern National Monuments office in Arizona, received copies of these reports, and noted that Tornillo Creek would be useful for its dinosaur fossils. Maxwell and other NPS officials also championed extending the CCC work out of the Chisos basin, so that the range of experiences for visitors would highlight the landscape of the Big Bend country. Thus the news that the King suit had been settled, and that land acquisition could advance, came as the NPS had a satisfactory inventory of natural resources and acreage for the future national park. [7]

Given less than 150 days to acquire over 700,000 acres of land, the land department began by purchasing from the state of Texas its portion of school lands (221,636.10 acres) for about two dollars per acre (with mineral rights constituting about half of the cost). Thereafter the land department secured commitments from 125 individuals with the largest holdings to sell (376,398.55 acres). Thompson had to initiate 57 condemnation proceedings against nearly 3,000 owners, with legal fees reducing the monies available to pay for the land. As the August 31, 1942, deadline approached, Thompson realized that his office had expended the entire $1.5 million state appropriation, leaving no monies for administrative tasks or purchase of the outstanding parcels. Amon Carter and the Texas Big Bend Park Association agreed to provide nearly $8,400 in donated funds, while local chapters of the organization advanced that total to $15,169.25. Thus the land department could operate until September 30, with some twenty parcels of land (13,316 acres) not acquired within the future park boundaries. With their valuation set at $64,000, the land office recommended that the association raise more private funds. [8]

The early success of the Big Bend land-acquisition program pleased park advocates from Alpine to Austin, and from Santa Fe to Washington. By the end of 1942, acting Interior secretary Abe Fortas approved of the boundaries that would comprise Big Bend National Park, while NPS director Newton Drury called the campaign "'a really great accomplishment.'" The efficiency of the land department staff appealed to Drury, who then asked the state parks board for copies of the procedures used, in the words of James Anderson, "to serve as a guide for the same type of programs in the future." Texas lawmakers especially praised the land department's overhead rate of merely four percent, which they described as "'in all probability an unparalleled record in itself.'" Texas Governor Coke Stevenson claimed that the land value exceeded $3 million, while Amon Carter estimated the Chisos acreage alone to be worth $1 million. All that remained was for Governor Stevenson to present the deed to the purchased lands to NPS regional director Minor Tillotson in a ceremony on the campus of Sul Ross State College. Joining the governor and Tillotson on September 5, 1943, were members of the land department, state senator H.L. Winfield, and Sul Ross president Howard Morelock. One last-minute detail remained: the acknowledgment by state officials that the federal government would have "exclusive jurisdiction" over Big Bend National Park. Governor Stevenson would accept this condition on December 20, 1943, when he signed the "deed of cession" requested by Interior secretary Harold Ickes. [9]

Concurrent with the land-acquisition strategy of the state of Texas, NPS officials pursued development and planning strategies from 1940-1944 that would ensure a smooth transition to park status for Big Bend. In February 1940, Conrad Wirth would advise the regional director of the plans of the CCC to expand upon the work of the camp undertaken from 1934 to 1937. When officials of the US Army, CCC, and NPS returned to the Chisos Basin, they would have in place some seven miles of truck trails, six miles of horse trails, one latrine, 2,000 feet of pipelines, ten acres of landscaping, and a parking area. Harvey Cornell, now the NPS's regional landscape architect, would comment in March 1940 on the master plan for Big Bend. Cornell could report that the state highway department had included the entrance route from Marathon to the state park in its system. The architect did note, however, that there existed a "general plan requiring that a major road closely parallel the Rio Grande River for military protection." Thus the NPS would be asked to provide a western park entrance near Terlingua; a condition that might satisfy Alpine boosters seeking road construction to the southern park of Brewster County. Cornell did not recommend any routes into the park from the east, as "it appears that the one important entrance will be located at Boquillas." [10]

Cornell's report also examined interior routes in the Big Bend area, with his recommendation of a road from Persimmon Gap southward to Boquillas, "and a connection between the Basin and the possible west entrance near Terlingua." The NPS could build secondary routes to Santa Elena Canyon, "and a road leading from Boquillas to Mariscal Canyon." Less important would be "a circulatory road on the American side of the Rio Grande," as he predicted a similar route on the Mexican side of the park. Cornell advocated that the lodge and visitor services center be placed in the Chisos basin, as "the series of Juniper flats above the originally proposed lodge site afford an excellent area for the construction of cabins." In addition, said the architect, "the view from these flats through the Window is most dramatic." Cornell disliked, however, NPS suggestions to place campgrounds in the basin. He preferred Pine Canyon, "referred to locally as Wade Canyon," where Ross Maxwell had identified a supply of water. Pine Canyon could be reached from the Boquillas road, but Cornell believed that "a much shorter alignment is possible as a direct connection between Pine Canyon and the main Park road just north of the Basin." [11]

In the matter of administrative facilities, Cornell anticipated "a large number of buildings, including residences for Park employees." He cautioned his superiors that "the various sites previously under consideration appear to be exposed to views from the main park road." Thus he recommended "a site north of the Basin and on the east side of the main park road," as this met "space requirements and was quite thoroughly screened from the main park road." He also opposed any facilities in the area of the South Rim, but did conceive of "a minor development affording overnight facilities adjacent to the South Rim," with access gained by a tramway from the Laguna area. Cornell further advised the NPS to plan for a longhorn cattle ranch, as "a large number of park visitors will be interested in the usual ranch activities common to West Texas." He believed that "if a Ranch is established in this area we doubt if local private interests would criticize the competitive nature of the development as the nearest 'Dude' Ranch would be many miles distant." He concluded his assessment of the planning of Big Bend by observing that "very little study was made of the possible park development in the adjoining area in Mexico." He surmised that "the most interesting portion of the proposed park is in the vicinity of the Sierra del Carmen and the Fronteriza Mountains ranges," and thus spent no time on the Chihuahua side of the Rio Grande. [12]

As the CCC camp undertook the task of preparing Big Bend for its inclusion in the NPS system, the park service in March 1941 sent a team of inspectors to review their work. John H. Veale, assistant regional engineer, accompanied Ross Maxwell and other staff members on a survey of the water-supply and sewage-disposal facilities in the Chisos Basin. They viewed the cabins under construction, and noted the work in adobe brick-making. Maxwell spoke at some length in a report to the regional director about the process of adobe construction. The NPS's regional geologist commented that CCC crew members "are using a weathered calcareous shale which is obtained from near Terlingua at the same site from where most of the adobes in the buildings at Terlingua were made." Maxwell conceded that "this clay is mixed with sand and the results appear excellent as compared with most adobes." Yet the geologist worried that the crew was "attempting what is almost 'the impossible,' an adobe brick with perfectly square corners, straight surfaces, and sharp edges that can be laid in a wall as perfectly as high-grade brick." John H. Diehl, the NPS regional engineer, offered a more optimistic report about the work on the sewage disposal unit. He told the regional director that "there is practically no possibility of contamination to the creek or Oak Springs, which are at elevations considerably lower than the development area." Diehl also believed that "the site . . . is far enough distant from the development area to avoid any odor nuisance, and can easily be screened for landscape purposes if this should become necessary." [13]

The comments of the review team, especially Maxwell's criticism of the adobe-brick process, prompted the Santa Fe regional office to consult with associate architect Lyle Bennett. J.E. Kell, acting regional chief of planning, reported to the director that Bennett considered Maxwell's assumptions "'entirely incorrect as it was intended that the adobes should have "sound" faces rather than "perfect" faces.'" Kell reminded his superior that "'the first adobes made showed disintegration of one-half inch or more of the faces and that many had lost the original faces entirely from disintegration and internal stresses.'" Bennett wanted adobe that had "'some chipping of edges and bulging, roughness, or irregularity of faces'" because "'that is the natural character of adobe brick.'" The associate architect noted to Kell that the NPS's southwestern region already had "'received criticism from various sources because of the "perfection" of masonry work and the amount of waste rock.'" Bennett contended that "'too much cutting of stones is going on in an attempt to arrive at some preconceived perfection of line and surface.'" Even though the NPS had instructed its CCC crews at Big Bend and elsewhere that "'a stone veneer was not sound construction because it produced a weak wall,'" and that "'this pattern is neither economical for natural stone nor does it bring out the most desirable natural qualities of real stone,'" Bennett had to admit that "'it is still evident that the square and chisel are being overworked in an effort to force a naturally irregular material into an unnatural regularity, thereby losing some of the best qualities of the material.'" Bennett wanted Kell to know that "'disregarding the fact that we are trying to reproduce . . . a Mexican hut of very honest construction," the NPS should remember that "'the people who will rent these cabins will be more pleased with a structure which has character, informality and softness in line and texture, and a general atmosphere inducing relaxation, in contrast to hard, precise, sharp, and perfect lines and contours of a more sophisticated structure.'" [16]

The thoughts of senior NPS engineer E.F. Preece, however, were more pointed and critical of the overall work of the CCC, and of the park service's plans. Preece spoke harshly in his report of April 28, 1941, of the NPS's strategy of "spraying the walls with a paint or preservative coating of some sort." This, said Preece, "has been proven so definitely unsatisfactory that it is difficult to understand why we continue to try to do something which we know will not work." Preece complained that "for years now this Service has been using every kind of material to preserve adobe ruins," only to realize that "there is not a single record of even mediocre success and an attempt to paint the adobe bricks at Big Bend will meet with no better success." The senior engineer thus recommended that "this proposal be completely abandoned." [17]

Preece further criticized the CCC's efforts to locate the visitors center and administrative headquarters below the Chisos basin. "This location," wrote the senior NPS engineer, "must be considerably hotter than the higher elevations in which the vegetation is much more varied and certainly more profuse." As the NPS needed to consider "the comfort of those who must eventually use the headquarters," he argued that their needs "should outweigh whatever indiscernible consideration dictated its presently proposed location." Preece then addressed the master plan's call for a cog railway to the South Rim. "I understand the reasons back of this suggestion," said Preece, "and certainly agree fully with them." He remarked rather sarcastically that "it must be possible for the obese lady from Iowa to visit the rim and a road scar is far too great a price to pay for this accessibility." The senior engineer then suggested replacing the cog railway with a monorail, which he believed "is completely practicable [and] will not require even the removal of vegetation in any important degree." Preece also thought that "the monorail will be simpler to operate than a cable car and should be much less expensive to maintain." [18]

Preece's remarks provoked substantial discussion among NPS architects, with Harvey Cornell responding to the NPS director's call for an explanation of the problems at the CCC camp in the Chisos Basin. Cornell disagreed with Preece's claim that the headquarters site could not support adequate vegetation, noting that "there are no other sites that would be easily accessible and still afford adequate space on reasonably adaptable terrain." He then challenged Preece on the issue of the cog railway to the South Rim. Cornell and other park designers realized that if "the usual pressure for a park road should become acute, then our preference would be for the cog railroad, but only on the assumption that one or the other would have to be provided." He preferred horse paths to the rim, and suggested that "if the bridle trails are of sufficient width, small mule carts might be adequate for those park visitors who absolutely refuse to use bridle and foot trails in the normal fashion." Cornell added that "at least this method of conveyance would be novel and would seem entirely in keeping with local precedent." As to the adobe brick controversy, Cornell told the NPS director that Lyle Bennett had offered more elaboration of his thoughts. Bennett admitted: "'I cannot defend a job which is so far from the results intended as regards appearance.'" Yet the associate architect contended that "'it is questionable whether more supervision by this office would have greatly improved results unless someone with the experience to understand and execute the kind of work desired were available to devote full time supervision to the job.'" Cornell concluded that future construction work at Big Bend needed "the continuous direction of a supervising architect," with an example being the "arrangement followed at the Painted Desert Inn, Petrified Forest National Monument." He also reminded the NPS director that "the successful adaptation of the provincial Mexican style of architecture, with the colorful blending of native materials into a natural setting, should not be too difficult to accomplish." [19]

The merits of adobe construction at Big Bend paled in significance for NPS officials when the US Army announced plans to close CCC camps deemed non-essential to the anticipated war effort. John C. Diggs, inspector of CCC camps in Texas for the park service, asked that "Big Bend NP-1" (the Chisos facility) remain open, and that it remain connected to his office "where easy and frequent contacts will be maintained with the Texas State Parks Board and the group of people who are raising at least part of the funds to make the land purchase." The camp was spared from the Army's budget cuts, and by October 1941 the military had asked the park service to construct four adobe dwellings for the contingent of Army management personnel in the Chisos basin. Raymond Higgins, NPS field supervisor for Big Bend and other Texas CCC camps, noted that the Army's request placed the park service in a bind. "To be eligible for consideration," said Higgins, "the structure involved should be a camp building appearing on the approved standard camp plan." The Army could not order the CCC to build facilities for them in the Chisos Basin, said the field supervisor, nor did the CCC have the authority to construct dwellings outside of the camp perimeter. Higgins suggested as a solution the building of permanent structures for the Army the NPS could acquire after the war. His agency's lack of funding also compelled the Army to use its own monies, and Higgins noted that without emergency conditions, the Army would have to follow standard procedure for design, ordering materials, and acquiring the services of the CCC crew then in the basin. [20]

Late in the evening of December 26, 1941, the CCC camp experienced its most traumatic moment when the museum building, which contained the artifacts, specimens, and records of the scientific research conducted at the future NPS site, burned to the ground. Built in the spring of 1936 as a "temporary laboratory," the structure had been renovated in the summer of 1941, as Lloyd Wade had used the building from 1937 to 1941 as his living quarters while the CCC camp sat abandoned. The facility had been maintained since then by the Army, with periodic checks by camp employees to guard against fire. Then about 3:00AM on the 26th, the night watchman, Manuel Leon, noted flames leaping from the north end. "Prompt efforts to check the spread of the fire," wrote Higgins, "or to extinguish it were unsuccessful and the building and contents were completely destroyed in 10 or 15 minutes after the first was first noticed." Higgins dismissed the usual causes of combustion (faulty wiring, defective stoves or heaters, chemical storage, waste, lightning, etc.). Instead he speculated that "the fire resulted from the actions of pack rats which virtually infest the camp." The NPS field supervisor thought that "a pack rat might have brought ordinary, or 'non-safety,' matches to a storage place or nest under the building." Friction might have ignited the structure, as there had been no rain for three weeks in the Chisos Basin. All that Higgins could recommend was for the CCC to "construct all frame buildings sufficiently high from the ground to permit periodic inspections to detect and remove [pack rats'] nests and storage places from below the floor." [21]

For Ross Maxwell, the destruction of the CCC museum had grave implications for the future of interpretative programs at Big Bend. He reported to the Santa Fe regional office that he had devoted three years to the collection and identification of the specimens and artifacts consumed in the December 26 fire, and especially regretted the loss of the materials used in compiling his geologic map of the park area. Maxwell noted that he had spent his days collecting specimens, with his "off-duty" evenings devoted to curatorial work. He had employed four student technicians, thus managing to process some 2,225 geological specimens. "A few of the larger rock specimens," wrote Maxwell, "are only slightly damaged, but virtually all fossils, including dinosaur bones, crumble when picked up to remove from the ashes and charcoal." CCC workers tried to salvage what rocks they could, but Maxwell surmised that "it is doubtful if 2% now have value for exhibit purposes." For these reasons the NPS geologist lamented that "to place a value on the specimens is virtually impossible." Beyond the staff time and money invested in the museum, the park service now would have to conduct another series of surveys to replace the rocks and artifacts, if such could be located again. Maxwell also dismissed most potential causes of the fire, with the possible exception of arson. "There are," said the geologist, "a few people in Brewster County who are not in sympathy with the park project." He speculated that "someone might have taken this method to slap at either the Park Service or the writer." Maxwell also did not discount the possibility that "one of the [CCC] enrollees might have started the fire because of a dislike for one of the personnel." Yet a third consideration, reported Maxwell, was that "one of the enrollees is a 'fire bug.'" [22]

The implications of the Big Bend museum fire prompted NPS officials in Santa Fe to issue recommendations for all work projects within Region III. Natt N. Dodge, acting regional naturalist, suggested that all structures used "for the housing, storage, or display of museum exhibits and collections or scientific specimens shall be of fireproof construction." If this meant temporary storage off-site, Dodge preferred that to the threat of fire like that witnessed at Big Bend. He also wanted CCC supervisors to redesign their camps with fire protection as a high priority. Dodge did not want to frighten away researchers with the potential for damage to their findings, as he believed that "research is essential both to an accurate and complete knowledge of the primary values of Service areas, and to a clear and accurate interpretation of those values to the public." Dodge contended that "scientific specimens and study collections constitute as much a portion of the natural values of these areas as the scenery, the plants and animals, and the other resources" that the NPS mandate required. Thus the provision of "fireproof, weatherproof, and verminproof structures for the protection of these invaluable public collections . . . is a recognized duty of the National Park Service which must not be neglected." [23]

Two months after Dodge released his findings on fire protection, the issue became moot for Big Bend. On March 21, 1942, the NPS announced the closure once again of Camp NP-1, with "Company 3856 White Juniors" transferred out of the Chisos basin. The regional office discovered, however, that word of the abandonment did not reach Big Bend for several days, as the facility lacked telephone or radio service. This did not stop Paul V. Brown, chief of the region's division of recreation land planning, from conducting his own inquiries about facility development in the future national park. One issue that concerned Brown early in the process was reference in the region's files to "a possibility of a selection of one of the canyons within the proposed park boundary for water storage." Writing on April 15, 1942, to Earl O. Mills, planning counselor for the National Resources Planning Board (NRPB) in Austin, Brown noted that a publication of the University of Texas for the International Boundary Commission referred to "a Big Bend Dam Site in Boquillas Canyon." Brown also found mention in the minutes of the first meeting in January 1940 of the "Lower Rio Grande Basin Committee" of a "Rio Grande Water Reservoir possibility" in the same location. Further confusing Brown was any reference in NPS files to a decision by Mill's office "recommending that the National Resources Planning Board undertake a fact finding study of the Lower Rio Grande Drainage Basin. [24]

Brown's work on the Big Bend master plan led regional director Minor Tillotson to praise his findings to the NPS director in Washington. On April 28, 1942, Tillotson sent to park service headquarters Brown's report, along with his own recommendations for the Texas NPS unit. Tillotson's first consideration was "promotion of the International aspect of the area." This should begin, said the regional director, with "early establishment of a contiguous National Park south of the Rio Grande." From there the NPS and Mexico should consider "the park area on each side of the river as a single unit without too much regard for the political boundary and, as Mr. Brown states, in such a way that the two areas will serve to complement rather than to compete with each other." This would lead, in Tillotson's estimation, to "free interchange of travel between the two sections of the International Park just so far as Customs and Immigration regulations can be modified to permit." Along with this would be "maintenance of the 'border' atmosphere of old Mexico," and "retention of certain typical Rio Grande trading posts and eating places." Then the regional director encouraged Washington officials to preserve "the spirit and atmosphere of early-day Texas" at Big Bend, with "the park to be essentially a saddle and pack horse area, rather than one through which the automobile will be the principal means of transportation." For Tillotson this meant "emphasis on the development of trails and camping places rather than on high standard roads and hotels," with accommodations akin to "ranch house and frontier days type." Finally, Tillotson suggested that the NPS plan accommodations for two seasons of visitation, with summer visitors in the Chisos Basin and "the Rio Grande for the winter visitors." [25]

Brown's own narrative about planning for the new national park revealed the power of the border, the need for better relations with Mexico, and the imperatives of World War II on the park service's imagination. The regional recreation-planning chief noted that "Mexican music and the colorful characteristics of Mexico definitely have influenced the music, the dance and the art of this country." In addition, "the economic and political relationship of the two nations as well as the blending of cultural sympathies is becoming more and more of vital importance." As Brown considered Big Bend to be "in the very heart of this land of romance and frontier lure," he hoped that the NPS would make it "the particular park of the National Park System where the Mexican and Texan scene may be experienced in reality by the vacationist." He believed that this interpretation of a shared cultural frontier was inevitable, as "the area will always reflect the Mexican and Spanish influence and will serve to introduce the two people to one another." Brown speculated that "when international highways connect at the park, as should be anticipated in our planning, the gateway function of the area will be greatly enhanced." The lure of the exotic for visitors, said Brown, required the NPS to "contemplate and encourage" development of accommodations south of the Rio Grande. "The planning theme," Brown continued, "must be towards retaining that unique atmosphere which is conducive to appreciation and understanding of the wide open spaces." He also suggested that NPS planners think of "the simple primitive relationship of man to rugged lonely landscape," of the "inter-dependence and friendship between a rider and his horse," and of the "ever-welcome mountain landmarks that keep the explorer from being 'lost.'" [26]

Turning to the realities of park design, Brown noted that "our planning premise should preclude the possibility of elaborate structures and architectural intrusions." For the regional official, "only an absolute minimum of essential park roads should disturb this vastness of unperturbed nature." Brown considered it "not possible to sense the lonely magnitude of such a country from the security of an automobile on a smooth highway having known terminals." He hoped that "on the dim bridle trails between overnight camps or rest stations, it is to be expected that in some spacious grandeur of unhurried nature the park visitor will regain some of that mental poise and perspective with which to better evaluate life's purposes and social objectives." Brown conceded that Big Bend would not attract "the sensation hunters, those restless thrill seekers rushing across the country from one exploited phenomena to other spectacles and sports arenas." Big Bend "is a country that needs no exploitation, nor man's superimposed attractions." Brown surmised that "many will come out of curiosity and in response to the prestige of a national park name." Yet "only a relatively small percentage will remain to experience a true appreciation of the fascination of the park and what it provides in the way of the proper use of leisure and recreation." [27]

The NPS planner also contemplated the visitation patterns of such a place as Big Bend, noting that "we may be influenced by [wishful] thinking in predicting that from the populous eastern seaboard a heavy winter traffic by way of New Orleans, Houston, and San Antonio will eventually flow into the Big Bend." Brown also estimated that "the Great Lakes States, including the Chicago district, will route winter tourist travel through St. Louis, Dallas, and Fort Worth into the Big Bend country in response to the appeal of such a park as planned." He hoped that "much of the winter travel will have Big Bend as its terminal objective or a scheduled stay of several days in the park." Then the NPS could anticipate that "the great population of Texas alone practically assures ample use of the cool mountains of the park during the summer months." For these reasons, Brown compiled a "travel analysis" that calculated "approximately 1000 visitors coming into the park daily during the peak of the summer tourist season." These visitors would arrive in 300 automobiles, with one out of six seeking camping facilities. "This would leave 250 families daily seeking cabin or lodge accommodations in the park," wrote Brown, "since we feel that only a very small percentage will attempt to loop through the park from the distant highways in one day without an overnight stop." Campgrounds should be built for an average stay of three nights, said Brown, with Pine Canyon "admirably suited, provided it can be connected by park roads with the Green Gulch entrance road at or near Moss Well, via Smugglers Gap." [28]

Brown's study of campgrounds in Big Bend emanated from his belief that "the average tourist has become accustomed to the use of auto camps." By recognizing this phenomenon, said the recreation land planner, "the introduction of auto camp facilities in Pine Canyon would relieve the pressure for DeLuxe cabins in the Basin and, in that event, we would reverse our estimates for campground capacity to read 250 cars per day into Pine Canyon and 50 cars per day into the Basin during the summer peak." This pattern of visitation would require "bridle trails out of Pine Canyon connecting with the South Rim trail, perhaps at Boot Springs." Brown also speculated that "visitors will desire to take auto trips to Santa Elena and Boquillas Canyons." There the NPS would need "ranch accommodations," which Brown described as "bunk house, mess hall, and sales room for local handicraft, short-orders, and drinks." He then offered as potential visitation an average of 600 to 800 in June, 800 to 1,200 in July, and 1,000 to 1,500 in August. After Labor Day, Brown anticipated a natural shift of emphasis down to the Rio Grande, leading him to suggest "that consideration be given to the locating of the center of activity in the vicinity of San Vicente and Boquillas." He believed that "the principal activity will be absorbing sunshine and the engaging in ranch type activities; such as horseback riding, plus boating and fishing." Brown looked for "some auto tours to the mountains, to Santa Elena Canyon and to the proposed Longhorn Ranch." NPS planners thus should prepare for "a daily population of 600 to 1000 during the winter." When added to his estimate of 12,000 visitors monthly in the summertime, Brown concluded that Big Bend "would have an annual attendance of at least 200,000." [29]

Once the Big Bend master plan reached Washington headquarters, NPS officials began to round out the contours of the future park site. By early June, NPS director Newton B. Drury advised Minor Tillotson that the regional office should plan for a series of roads that included a main route from Persimmon Gap to the Chisos basin by way of Grapevine Hills. Drury disliked the proposal for a main road across Smuggler's Gap to Pine Canyon, and on to Hot Springs and Boquillas. He did agree, however, that "a route be sought that passes around the eastern side of the mountains to Boquillas Crossing." These also would be "the only roads in the park built to PRA [Public Roads Administration] highway standards." Drury then wanted the regional office to remove from the park "the road from Santa Elena Canyon generally paralleling the Rio Grande to connect with the Boquillas Crossing road." The NPS director also believed that "the desert type road paralleling the eastern boundary near the proposed Longhorn Ranch location is satisfactory." [30]

In matters of facility construction, Drury believed that "we should avoid any attempt to locate headquarters within the mountain area and that a study should be made as to the possibility of developing an oasis for headquarters along the main road system." The NPS director considered "the Grapevine Ranch site . . . to be the most obvious and feasible location." If regional officials "thought that this is not centrally located enough," wrote Drury, "and that headquarters should be nearer to the junction of the road leading into the mountains, or to the junction of the road leading to Boquillas, such a location would be given favorable consideration if adequate water can be obtained." For Drury this meant "a location 3 or 4 miles west of the junction of the road leading into the mountains," with water piped from Oak Springs some three to five miles away. The NPS director then turned his attention to visitor accommodations, stating that "the cabin area will be the only facilities provided in the mountains." Drury was emphatic in declaring that "in no circumstances should anything be planned for the present CCC campsite, and the camp itself should be removed and the roads to it obliterated, in order that the area might, at an early date, begin to restore itself." Drury then referred to the upcoming visit to Big Bend by his associate director, Arthur Demaray, who would "review the first year's estimates for administration, maintenance and protection." Demaray also would "give particular study to the tourist facilities which may be operated by the National Park Concessions Inc. " The associate director hoped to identify "what can be provided in the way of tourist accommodations in existing facilities for the first year's operation," and then offer "proposals for the development of more permanent facilities." [31]

Reference to the National Park Concessions, Incorporated (NPCI), indicated the NPS decision upon a concessionaire for Big Bend. Minor Tillotson approved of Drury's decision, writing in July of 1942 to the Texas state parks board of his friendship with W.W. Thompson, president and general manager of the Kentucky firm of NPCI. "Not only is Bill Thompson a swell fellow and an old personal friend of mine," Tillotson informed the state parks board's Frank Quinn, but he had "many years experience in the operation of the hotel properties in Mammoth Cave National Park." The park service had worked with NPCI in the 1920s and 1930s to open concession facilities in smaller and more isolated parks, especially those which would not attract bids from the major concessionaires more interested in the profits to be had from parks like Yosemite, Glacier, and Yellowstone. NPCI had entered into an agreement with the park service as a "not-for-profit" operation, with all revenues generated beyond actual expenses reinvested into the plant and equipment of NPCI's facilities. [32]

W.W. Thompson's visit in 1942 to Big Bend did not eventuate in plans for concession facilities, as another potential occupant of the area, the U.S. Army, studied placement of a training facility in the Chisos Mountains. Bob Hamilton of the Big Bend Land Department in Alpine informed Ross Maxwell that "the Army has been after me to give them correct information about the water supply, as they have plans of placing a cavalry detachment in the CCC barracks." Hamilton knew that "Messrs. Drury and Wirth are very much against any army group moving into the old camp," but the land department was "behind the '8-ball' for reasons that I cannot place in writing." As Hamilton needed to file a water-supply statement with the Army, he asked Maxwell: "If you can gracefully give me another report that would not be so favorable it would be better for all concerned." Milton McColm, associate regional director, likewise warned Lloyd Wade "to protect the Service and your interests [as CCC camp caretaker] against any unauthorized salvage or removal of the property still under our custody and accountability." McColm had learned that the Albuquerque District of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, tasked with acquisition of wartime materials and structures for use in training centers, had targeted Fort D.A. Russell for such training, with supplies transferred to Marfa for use by the Army. [33]

Wartime exigencies also revived the issue of water-storage reservoirs on the Rio Grande within the boundaries of the future national park. Paul Brown and Minor Tillotson had traveled to El Paso in May to meet with Lawrence Lawson of the IBC. Among the topics discussed were "the possibilities of dam construction and power development on the Rio Grande in the Big Bend area." Although there originally had been a dam projected in or near Boquillas Canyon, the tentative plan now would place this farther downstream near Sanderson. In so doing, the IBC would "take advantage of the inflow to the river between Boquillas and Sanderson, to shorten the length of transmission lines necessary, and to locate the dam site at a point where it would be more accessible to rail and other transportation." Tillotson then received in late August a copy of Confidential Bulletin No. 112, issued by the National Resources Planning Board (NRPB). This contained what the regional director called "a description of a proposed dam 'on the Rio Grande at Big Bend Area south of Marathon, Texas.'" Tillotson thus inquired of Lawson whether "tentative plans have again been changed or if the description of the project mentioned in Bulletin No. 112 is erroneous." The IBC commissioner eased Tillotson's fears by reporting that his survey crews would work south of Sanderson to the juncture of the Rio Pecos and the Rio Grande, and noticed that the NRPB had sought a comparison in cost of a dam near Boquillas with the preferred site at Del Rio. [34]

Pressure for increased access to natural resources to support the war effort extended to criticism of NPS policies prohibiting production of candelilla. Drew Pearson, a nationally syndicated columnist for the Washington Post, wrote a column that appeared in the Dallas News of October 26 entitled, "Gas Masks or Parks?" Pearson, whose "Washington Merry-Go-Round" columns were read by millions weekly, noted that "'to make a scaling compound for gas masks, the War Department requires a certain wax obtained from the candelilla plant, found only in hot, arid regions.'" The columnist had learned from Charles T. Wilson, whom he described as a "'New York millionaire,'" that the latter had leased property in the Big Bend area "'for exploitation of the plant.'" This included construction of "'a factory near Marathon, Texas,'" with Wilson's employees sent out to "'gather the weeds which heretofore nobody had been interested in except the burros.'" Then Wilson claimed that "'officials of the State of Texas intervened saying the property was desired as part of the Big Bend National Park,'" with "'Wilson and his wax gatherers . . . ordered off the premises.'" Pearson complained that "'so now the deer and antelope, instead of gas-mask wearers, will have the benefit of the candelilla.'" [35]

Eugene Thompson responded to Pearson's column by noting in correspondence with Conrad Wirth that "since all newspapers had given the Park so much favorable publicity any controversy should be guarded against." The state parks board believed that "whatever harm the article would cause had already been done and that any correction or retraction that Mr. Pearson might make now would not reach the same people his original article reached." Yet the state parks board wanted Wirth and NPS officials to know that "Mr. Pearson's article left the impression that Mr. Wilson had discovered some valuable plant that could be used in the construction of gas-masks and built an expensive plant." Thompson disagreed, noting that candelilla "is plentiful and is used primarily for floor wax while the plant he built was cheap junk and as far as we know never paid for." [36]

Charles Wilson's complaint that Big Bend National Park denied him access to wartime resources had a more humorous counterpart in the rumor that the NPS would construct within the park an exact duplicate of the "Jersey Lily" saloon. Regional director Tillotson had learned of this story from E.R. Beck, of Fort Hancock, Texas, and asked the NPCI's W.W. Thompson his thoughts on the matter. "From your knowledge of the West," wrote Tillotson on December 22, 1942, "or from having seen Gary Cooper in 'The Westerner,' you probably know something of the self-styled 'Judge' Roy Bean who set himself up as 'the law West of the Pecos,' dispensing justice in his own peculiar style from behind the bar of his saloon known as the 'Jersey Lily.'" Tillotson noted that "this structure still stands in the little town of Langtry, Texas, where it has been preserved by the State as a historic site." The regional director wrote that "the Big Bend is 'West of the Pecos' and in the general region over which Judge Bean held judicial sway," and that "it is our hope to preserve in the Big Bend area the spirit of Texas frontier days." With that in mind, Tillotson wondered of Thompson if "it might not be altogether out of place to have, instead of a cocktail lounge that would go with the usual type of hotel concession, an old-time Texas frontier saloon built as a replica of the 'Jersey Lily.'" Tillotson knew that "under present legislation there are no open bars in Texas for the sale of hard liquor," and that "the sale of liquor in the original package and of beer over a bar is regulated by local option," although Brewster County allowed such sales. Tillotson told Thompson that he had not seen the saloon that Beck wanted to sell to the NPS, but promised in closing: "If this bar were properly stocked with some of your well-known Kentucky products, I would like to own it personally." [37]

Of all the suggestions for wartime use of Big Bend and its future NPS site, none had the emotional power of a haven for wounded veterans. Bert Clark of Houston, Texas, who identified himself to NPS director Drury as a park service "collaborator," or private citizen advising the service on matters of policy, suggested that Big Bend "be made an up to date natural playground, a resort in fact but entirely different from our present Parks." Clark wanted NPS planners to "eliminate the costly installations, the old mid-Victorian hostelers, [and] the COSTS of visiting the Park." Instead the Houston-based collaborator would "simplify it, use the salvaged materials from the war, set up a lot of comfortable, clean houses like an auto camp but more detached, a play ground for children, and landing fields for planes, radio telegraph with the outside." These unusual accommodations Clark would offer to "ex-service men and their families at costs which could be met from their pensions." Clark considered his plan "an outstanding thing, not entirely a philanthropy or a health resort from the military standpoint, but nevertheless a haven of refuge for these washed-out men who have given their all to our Nation." Beyond these permanent residents, Clark "would likewise make it attractive to the week-ender, the man who can put his family there for the entire summer and commute by plane back and forth." Clark believed that this "revolutionary" dream "would make this Texas park a model of inexpensive perfection." [38]

Though Clark's plan bordered on the absurd, several of his observations attracted the attention of NPS officials. "Thousands of our lads will fly planes after this war," he told Drury, and he would "expressly stipulate in any concession to air-lines that this field is open to all comers, no monopoly," with a "passenger fare so low it could be used." Clark argued that "there are nineteen cities in Texas that can contribute a summer population to this park that will fill it." To do so would allow Texans to "enjoy our God given out of doors even for a day or two without a long, costly, burdensome journey to the distant mountains, always overcrowded." Clark worried that "the cost of visiting our present Parks can in many instances, be indulged but once in a life-time by great masses of our people who should enjoy these National projects paid for out of the National Treasury." Big Bend would have "a commissary where a meal can be had, an Army meal, for fifty cents." This Clark believed would eliminate "the Old Faithful dining-rooms and linen, the El Tovar." Clark had observed this elitism in his travels throughout the West, leading him to warn Drury: "The fights for lunch-counter food in the 'quick & dirties' is a disgrace, not to be vouched for by a Federal agency." He preferred to mimic "the auto camps in Arizona, California and elsewhere," describing the arrangement as "just a comfortable camping out place in grand natural surroundings, a respite from cities and heat." [39]

In Clark's dream of a utilitarian Big Bend, he would "surround this park with a game preserve, too large for the park's accommodations to be used as a spring-board to slaughter that game lured by salt-licks or otherwise, to the edge of the park." His goal would be "to create a distance too great to permit of the installations and operations of brothels, honky-tonks, rackets, etc. such as at Jackson, Wyoming near Yellowstone, and those near Sun Valley - a private enterprise, glamour." Clark wanted to "blot out these incubators of disease and worse, [to] keep Big Bend clean." The Houston collaborator contended that "the motor tourist in many of our Western trips, is sunk if he fails to gain the inside of a National Park before nightfall." Then the unwary visitor "just becomes so much fodder for these racketeers; remote, no chance to escape unless he carries his own camp outfit and even then it cannot always be used." Clark acknowledged that "the elaborate installations such as those at Zion [National Park in Utah] are not available to masses of people." Its lodges "are grand of course," said Clark, "but built for the accommodation of a wealthy patronage." Similar problems awaited Big Bend if the railroads developed transportation links to the park. Clark concluded that "Big Bend to my mind, offers the thing for which there is a great demand - the availability of the open to the masses." He claimed that "horse back riding is craved by youngsters and it is healthy, in that environment." Clark reiterated his desire for inexpensive transportation by air, with similar economies in visitor accommodations. "I would make the costs so low that all could afford it," said the Houston collaborator, "still keeping it neat, sweet and clean but free of elaborate, monumental, outstanding luxuries to which the masses are not accustomed nor do they want it." Clark had "traveled much, observed, shared the great benefits which a grand Government has established for me." In return, he asked the NPS to "popularize Big Bend - that would be the target at which I would set my sights." [40]

Bert Clark's vision of a worker's paradise on the border with Mexico did not fit with the plans of the NPS as the opening of Big Bend neared. By June of 1943, the state parks board announced that enough deeds had been executed to permit local park promoters to hold a transfer ceremony with the Interior department. Isabelle Story, editor in chief of the NPS, drafted a press release recounting the wonders of Big Bend, and the benefits accruing to the state of Texas for its work in acquiring 697,684 acres of private land. The park service wanted it known that Secretary Ickes appreciated the Lone Star state's diligence in spite of "successive periods of financial stringency, tense defense preparations, and actual war conditions." Ickes was certain that the state parks board could acquire the 15,236 acres still outstanding "which the National Park Service considers vital to the project." Isabelle Story then outlined the attractions of the nation's 27th national park. To familiarize newspaper readers across the country, the NPS noted that "Boquillas, in the southeastern part of the park, lies in the latitude of Daytona Beach, Florida," a reference to the popular tourist attraction on the Atlantic Coast. Story reiterated the praise of Big Bend's natural beauty and wilderness that suffused NPS publications and reports of the 1930s. Yet the park service's chief editor had to caution William Warne, director of information for the Interior department, that the final press release reflected the realities of race relations on the border. "Since the State of Texas has expressed disapproval of statements concerning the 'Mexican atmosphere' of the area," wrote Story, "we have regretfully deleted a proposed paragraph on that phase of the park." [41]

This last remark by Story revealed the depth of feeling still echoing throughout Texas regarding Mexico's nationalization of oil late in the 1930s, and also the history of border relations since the Texas revolt of a century before. The park service also faced the rising tide of political conservatism that accompanied wartime mobilization. Regional director Tillotson discussed with the state parks board the need to "make the actual acceptance ceremony as simple as possible." Tillotson worried that "if we made a big 'to-do' over the acceptance ceremony and had the Secretary, the Director, members of their staffs, and others gone to Texas for this ceremony, we would all of us rightly have been subject to public criticism for expenditure of the time and money involved during war times." Tillotson also reminded the parks board's Frank Quinn that President Roosevelt could not have attended, but that "we are all of us anxious--as I know you are--to have him take a prominent part in the formal dedication of the park." Thus the "more informality we can have in connection with the acceptance ceremony, the greater will be our chances to have a real celebration at the dedication ceremony." Tillotson cautioned Quinn that this meant waiting until the close of the war, "at which time I believe under the approved plan there would be an excellent chance of getting the President of the United States, the President of Mexico and the Secretary of the Interior to be present in person somewhere in Texas, preferably in the Big Bend National Park, at a formal dedication ceremony." Then the regional director reminded Quinn of the prosaic reality of land acquisition. Congress, through the intervention of Texas representative Ewing Thomason and Senator Tom Connally, had approved funds for the "administration, protection and maintenance of the Big Bend National Park during the present fiscal year." Without all land parcels deeded to the federal government, the NPS could not expend these funds. Yet Tillotson promised the parks board secretary that he would "have established the positions involved and to secure approval of the appointment of those selected to fill such positions, so that they may been entered on duty without delay immediately the park is established." [42]

Those latter details became clearer in August as Tillotson prepared his operating budget for the coming fiscal year. In a memorandum to all park superintendents within the southwestern region, Tillotson noted that the staff of Big Bend (which likely would be recruited from Region III park units) "will consist of not more than five persons." Among these would be "a Park Ranger at $2040 and a Senior Clerk at $2000 per annum." The regional director cautioned his superintendents that "the one ranger will have a 'ranger district' of some 713,000 acres," and he believed that "anyone familiar with ranger duties in a national park will know what that would entail, especially when it is considered that this is a brand-new park, without adequate improvements or equipment of any kind." Tillotson warned that park headquarters "will be some eighty miles from the nearest town--Marathon, Texas--and consequently a like distance from the post office, railroad, telegraph and telephone service, paved highway, schools, stores and churches." Employees would find that "the living quarters will consist of old CCC barracks," wrote Tillotson, "but there are water and direct current electricity in the camp." [43]

Then the regional director defined the key feature of character for new hires at Big Bend. "These are no jobs for weaklings or for those seeking 'light out-of-door employment,'" said Tillotson. NPS personnel could expect instead "very difficult assignments entailing much hard work and requiring the services of experienced he-men who have the ingenuity to make the best of a situation with limited facilities and the intestinal fortitude to cope with conditions along an unsettled portion of the Mexican Border--one of our few remaining frontiers." A more positive dimension of employment at Big Bend was that "the assignments will be most interesting ones for those who wish to pioneer in a new National Park Service project." Park personnel would find "unusual opportunities for advancement in the Service by 'getting in on the ground floor' of our newest national park, the sixth largest in the national park system, and one for which I foresee a most brilliant future." Tillotson then canvassed his superintendents for interested applicants, warning that "no one should apply who is not fully aware of the situation, willing and able to live, work and take care of himself under primitive frontier conditions, and ambitious to advance in the Service." The regional director acknowledged that "if an applicant is married, equally careful consideration will be given his wife and to her ability and willingness to live under pioneer conditions." He then closed with the admonition: "A working knowledge of the Spanish language is desirable but not essential." [46]

These prescriptions for staffing at Big Bend would echo down through the twentieth century, with the park's isolation, distance, complex ecology, and proximity to Mexico affecting park operations and personnel decisions in ways not experienced in most NPS units. The fact that the regional director had to warn superintendents that Big Bend was unique, at a time when most park units were isolated from urban centers, and were understaffed and under-funded because of the war, said a great deal about the challenge of management. Tillotson's references to the "he-man" qualities of the ranger corps at the park, and the concerns for families, also could be seen over the next six decades. Issues of employee housing, schools, social services, community maintenance, and race relations touched every superintendent's watch from 1944 through the start of the new millennium, even as the more conventional policy issues of resource protection and interpretation, visitors services, and community relations occupied any superintendent's day.

To address this challenge, Tillotson announced on September 14 that Ross Maxwell would assume the duties of superintendent at Big Bend. The geologist had earned the coveted post, said the regional director, "because his first assignment with the service in 1936 was the making of a detailed geological map of that area." Tillotson believed "that there is probably no one in the service who knows more about the region than he," noting that Maxwell had earned a doctorate from Northwestern University, as well as having held several positions within the southwestern region of the park service. Response to Tillotson's announcement in Brewster County was uniformly positive, as Glenn Burgess, manager of the Alpine chamber of commerce, told his good friend "Tilly" that "we have heard nothing but praise of the appointment of Ross Maxwell as Superintendent of the Park and we are looking forward to the time when he will be a permanent citizen of the Big Bend country." As for Maxwell himself, he owed a debt to Hillory Tolson, by then assigned to the NPS headquarters in Chicago. "Naturally," wrote Maxwell on October 12, 1943, "I think that the Big Bend is a great area, and I shall thoroughly enjoy taking you around." Maxwell praised the former Region III director as someone who "had a great deal to do with my former appointment to the positions of Regional Geologist and Assistant Superintendent, Southwestern National Monuments." He hoped that Tolson "can stay at least a week for it will take about that long to see the 'highlights'" of Big Bend, and Maxwell concluded: "I shall need plenty of advice on this new assignment and am anxious to get started as soon as practical." To Glenn Burgess Maxwell offered similar thanks, telling the chamber manager: "You can rest assured that I'll see the 'Alpine gang' every chance I get," with park headquarters and residences to be located "at the old CCC camp in the Chisos Mountains." [47]

Naming a park superintendent also meant that regional officials needed to address visitor services, especially a contract with NPCI for management of concessions. By September 1943, Tillotson still had not heard from NPS headquarters about NPCI's involvement at Big Bend, which he realized in a letter to W.W. Thompson might not occur until after the war. "In the meantime and until definite arrangements can be made to provide suitable accommodations for the visiting public," said Tillotson, "there are a few parties who have lived and operated in the area for the past several years." It was the park service's intention to work with W.A. Cooper, "who operates a little store and gas station on the main highway, south of Persimmon Gap," Baylor Smith, whom Tillotson described as "still located at the only postoffice, Hot Springs, Texas," the Hannold store "on the back road between the Basin and Hot Springs," and "last but not least, our old friend Maria Sada (commonly known as Chata), who operates a little store and Mexican restaurant at Boquillas." Tillotson would seek approval from the NPS director to permit "some or all of these parties to continue operations under formal special use permits." The regional director hoped that "such an arrangement would be satisfactory with the National Park Concessions, Inc., even if you have already entered into a formal contract." [48]

Tillotson then explained to the NPCI president how the park service intended to use the CCC cabins in the Chisos Basin as the core of future visitor accommodations. "With the establishment of the national park," wrote Tillotson, "title to these cabins along with lands and other properties involved will vest in the United States." When the CCC abandoned the basin for the last time, "Lloyd Wade, formerly a CCC foreman, whom you will remember, has been employed by the State as a caretaker." Wade had been given authority to manage the rental of the cabins, while his wife "has on occasion furnished meals to visitors in cases of emergency." The NPS had made "definite arrangements" to hire Wade as a foreman at the new park, "after which time he could not, of course, continue to operate the cabins." Tillotson worried, however, that "it would put us in an embarrassing position if, with these nice cabins available and no other place for people to stay, we had to tell visitors that they could not occupy the cabins because we had no one to operate them." The regional director instead had "in mind some sort of a scheme by which Mrs. Wade could be made responsible for looking after the cabins, either as an employee, or subcontractor of [NPCI}, when you enter into a formal contract, or under some form of direct temporary permit until that time." [49]

Throughout the fall and winter of 1943-1944, the park service could only wait and plan as the federal government anticipated word on the final cession of land deeds for Big Bend. Regional officials, rather than Ross Maxwell, had to manage the park from the distance of Santa Fe, leaving no one in the Big Bend area available for consultation on matters of local or state interest. Use of water resources in the future NPS unit required attention, as A.M. Mead of San Benito, Texas, pressed the state's congressional delegation to build a dam and reservoir on the Rio Grande within the park's boundaries. ""Now, as the Big Bend is a State and Nations Park," wrote Mead, "wouldn't it be grand to have a Big Lake in it, for boating, bathing, hunting and fishing." Mead even suggested a means for constructing such a facility. "Listen," he told Congressman Milton West of Brownsville, "a big dam across the Santa Elena Canyon, on the Rio Grande River, would do this job and the lake would catch all the flood waters and hold them in storage for Mexico and this Valley." Mead also suggested that "we could work those Nazi prisoners on this job and get the job done, and would have plenty of water for this Valley at all times." C.E. Ainsworth, a consulting engineer for the IBC, worried more about the contracts that his agency had with local ranchers to measure rainfall and operate stream-gauging stations on the Rio Grande. "This office has need for all available rainfall records from the Big Bend Park area," Ainsworth informed Tillotson, and the IBC wondered when Elmo Johnson and Albert W. Dorgan would no longer be able to provide the stream commission with this data. [50]

More troubling to NPS officials was the decision by the Texas state board to water engineers to revoke the permit of J.O. Wedin for use of 780 acre feet of water from the Rio Grande. Wedin's property was part of the future Big Bend, and constituted a substantial portion of the park's water supply. Wedin had been informed in November 1927 that his use of the stream-flow was predicated upon construction of suitable irrigation facilities within 90 days of receipt of the permit, with completion scheduled for no later than one year (the fall of 1928). In addition, Wedin was to file annual reports with the state water board "showing, among other things, the quantity of water used and the purposes for which it was used." J.E. Sturlock, attorney for the water board, neither could find a record that Wedin had filed his reports, nor that he had constructed his irrigation works. The state then ordered Wedin to show cause why his permit should not be revoked; a condition made more difficult by the delay in transfer of title to the park service. Fortunately for the NPS, Sturlock advised the water board to "defer further action in the matter of forfeiting and canceling [the permit] until such time as you have completed your development plan for the Big Bend National Park area." [51]

Yet another management issue awaiting the new staff of Big Bend was congressional action to create the position of United States Commissioner for the new national park. C.M. Meadows, owner of the Meadows oil company of San Angelo (and a member of a prominent Texas family), had campaigned for the position with state officials. "I should like very much to have a part in the development of the park," Meadows informed Maxwell on October 30, 1943, "and would also enjoy living in the area." Yet the San Angelo businessman had learned that Everett Townsend also was being promoted for the position. "No other would be better qualified than he," Meadows wrote, "and I know of no one who has taken an keener interest in the development and promotion of the Park than Mr. Townsend." NPS officials reviewed Meadows' comments with some enthusiasm, but E.T. Scoyen, associate regional director, noted in the margin of Meadows' letter that "if there is any way to avoid it don't get a full time commissioner who will reside in the park." [52]

Meadows' endorsement of Townsend for the commissioner's post highlighted the regard that local officials and NPS personnel alike had for the "father of Big Bend." Tillotson wrote on November 10 to the NPS director to praise Townsend for "promoting and securing the passage of legislation providing for appropriation of funds by the State, and in the actual land acquisition program." The regional director believed that "I am safe in saying that there is no other individual who has taken such an active part in the entire program from its inception or who has been so helpful in every way throughout." Tillotson then advised the director of the need for a commissioner once the state ceded control of the land to the park service. "In spite of his years," Tillotson said of Townsend, "he is in excellent health and fully capable of carrying on the duties of such a position." Citing his service of more than 40 years with the Texas Rangers, the U.S. Customs Service, as sheriff of Brewster County, and in the state legislature, Tillotson suggested that "by experience and training he is well qualified for the position and he would certainly be most acceptable to Superintendent-designate Maxwell and to this office." The regional director then approached Townsend with the offer to "have you in such a position, " as he considered it "most appropriate and fitting as a climax to your long years of effort toward the establishment of the park." Tillotson's offer flattered Townsend greatly. "I shall be very glad to have it," said the longtime champion of Big Bend, as he had spent a good deal of time working with U.S. commissioners' courts. "I know that Maxwell and I can team it together," he concluded, and would "deeply feel the honor of being the first U.S. Commissioner in the Big Bend National Park." [53]

By the spring of 1944, the park service could envision an opening date for Big Bend that solved the problem of hiring a U.S. commissioner. On March 9, Assistant Secretary Oscar Chapman had awarded NPCI the concession for Big Bend. Tillotson then called upon the park service to locate the main visitors complex on the Rio Grande near Boquillas at the Daniels Ranch property. "Here there is ample room for development and expansion togethere with plenty of water for irrigation, operation of air conditioning system, etc." The regional director still held out for an architectural design "on the lines of an Old Mexican Hacienda and every effort should be made to maintain the Mexican atmosphere of the place." The Chisos basin, by comparison, would get only lodges for summer visitors. "This entire development," wrote Tillotson on March 29, "should maintain the general atmosphere of a typical old Texas ranch layout," with "corrals . . . provided as the starting point for saddle horse and pack trips." Campgrounds could be built in Pine Canyon, said the regional director, and at Castolon, Boquillas, Hot Springs, or San Vicente. When the NPS constructed its food-service facilities on the river, said Tillotson, they "should be in the form of a typical Mexican restaurant somewhat along the lines of that formerly operated at Boquillas by Maria Sada." Visitors also could avail themselves of souvenir shops within the park, said Tillotson, "especially those of Mexican manufacture," and "there should be no ban on the sale of such foreign made articles as are manufactured in Mexico." Presaging an idea promoted in the year 2000 by park superintendent Frank Deckert, Tillotson told NPS officials that "I can also foresee a large business to be done by the operator in articles of clothing typical of the country, such as cowboy boots, bright colored shirts and neckerchiefs, ten-gallon hats, Mexican sombreros, charro costumes, huarachos [sic], etc." [54]

Tillotson's admiration for the visitor services provided over the years by Maria Sada struck a chord among NPS officials designing concessions at Big Bend. One week after noting that Sada had left the area to run a restaurant in Del Rio, Texas, Tillotson reported to the NPS director that "she has now returned to the Big Bend in order to 'collect some accounts due her.'" Sada had taken up residence upriver at San Vicente, and wrote to Tillotson asking for permission "to reestablish her former location now owned by the Government at Boquillas." Tillotson told Drury that "since there is absolutely no other place in the area where a visitor can secure a meal, it seems to me that it would be a distinct advantage from our standpoint to have her provide such service." The regional director preferred Sada to be located on NPS property, and thus Tillotson advised her to reoccupy her old establishment. "Personally," wrote Tillotson to Drury, "I should like very much to see her remain in the area with her little store and eating place until such time as National Park Concessions takes over and thereafter have her remain as an employee of the company conducting a typical Mexican restaurant in keeping with the border atmosphere." Thus the regional director offered both Sada and W.A. Cooper special-use permits to allow them to provide visitor services when the park opened on July 1 to the public. [55]

Maria Sada's permit reflected one of the most enduring dichotomies of the creation of Big Bend: the NPS's desire to tell the border story accurately (along with the other features of natural and cultural resource management), and the pressures from local interests to avoid references to partnership with Mexico. The Women's International League for Peace and Freedom, based in Washington, DC, called upon NPS director Drury in December 1943 to invite Mexican officials to any ceremony opening the national park. Mrs. Josue Picon, chair of the U.S. Section, Committee on the Americas, told Drury that such a gesture might "encourage our Mexican friends to hasten plans for the giving of a tract of land on their side opposite the Big Bend." Then in May 1944, Zonia Barber of Chicago wrote to Harold Ickes "to ascertain whether the contemplated Mexican Park on the other side of the Rio Grande is ready and willing to join the Big Bend Park in forming an International Park." Barber reminded Ickes that, "realizing the influence Symbols have on human action, as Chairman of the Peace Symbol Committee of the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom, I am urging that the new International Park be named 'Big Bend - (name of the Mexican Park) International Peace Park." Ickes should recall also, said Barber, that "each of us who has spent much or little time in Mexico realizes the necessity of using every available opportunity of expressing through action the 'Good Neighbor' policy" of President Roosevelt. [56]