|

Big Bend

Administrative History |

|

CHAPTER 7:

Clouds of War, Pleas for Help: The Big Bend Land-Acquisition Campaign, 1939

From the invasion of Poland in September 1939 by the armed forces of Adolf Hitler's Germany, to the fall of France and the humiliation of British troops at the Battle of Dunkirk the following spring, news of war and death overshadowed all other matters in the public's mind. At home, the transition from a peacetime economy to military preparedness moved awkwardly, complicated by the election in November 1938 of a conservative Congress eager to reduce or eliminate New Deal social-welfare programs and their perceived wastefulness. All of this portended failure for Texas's first national park, especially given the Lone Star state's dislike of taxation and government regulation. Yet prospects for funding the purchase of nearly 800,000 acres of land in the Big Bend, while dismal throughout much of this period, nonetheless remained alive and received a boost oddly enough from the very forces of war that threatened the lives of millions in Europe. By the close of the decade, then, park promoters stood ready for a final assault on the Austin capitol, with the strategies of this 12-month period both a continuation of and a break from the efforts employed for nearly a decade by sponsors of Big Bend National Park. [1]

Of utmost importance to NPS officials in Santa Fe was the 1939 session of the Texas legislature. Herbert Maier assigned W.F. Ayres, a park service inspector from the regional office, to monitor events in Austin. In addition, Ayres kept close watch on the intentions of the Fort Worth Star Telegram to initiate the multi-million dollar fundraising campaign for purchase of private lands. Ayres had gained experience with the Texas situation during his frequent trips to CCC camps in the Lone Star state. While conducting an inspection tour of sites in Brownwood and Cleburne, Ayres learned from James Record that "of the $25000. which [the statewide committee] had agreed to raise, $17000. was in hand and the remaining $8000 due from the Dallas contingent would be received in a day or two." Record also confided in Ayres that "a contract had been made with a national advertising company (Wychgell) to put the campaign on for $25000. and this would be started just as soon as the money was all received." State parks board president Wendell Mayes further advised Ayres that "bills had been drawn and were ready to be introduced by Senator [H.L.] Winfield." As far as Mayes knew, "it seems that [the bills] were only for the purpose of facilitating transfer of the land to the Federal Government for national park purposes, and not appropriation bills for purchase of land." The issue of mineral rights and school lands continued to endanger the future park, as Horace Morelock had informed Ayres of the reaction he had received when he spoke to the annual meeting of the Texas State Teachers Association. "Over his protest," Ayres told Maier, "the Assn. passed a resolution favoring the creation of a National Park in the Big Bend, but reserving all mineral rights on school lands for the State of Texas." Of major concern to Morelock and Ayres was the fact that "one of the principal sponsors of the resolution was Dean Shelby, of the University of Texas." "You know," Ayres warned Maier, "the story of oil on University lands." Given the fact that the parks board director, William Lawson, "expects a fight with economy minded legislators over appropriations for the Parks Board," Ayres agreed with Record that park sponsors should "do nothing about legislation at that time." [2]

Once Ayres reached Fort Worth, he met with the Star Telegram's James Record to coordinate the work of the park service and private interests. Record indicated that fundraising had not moved as expeditiously as Ayres had thought. Dallas and Houston had not sent in their equal shares of $4,000, forcing Record "to raise this part from other towns." The statewide committee had agreed with Adrian Wychgell to pay his New York firm $10,000 as salary for the campaign, with expenses controlled by the committee. Ayres then learned that "Wychgell's original proposition was to put on the entire campaign for $82,000." While the committee would not sign Wychgell's contract until the $25,000 had been raised, Ayres reported that "Record expects this to be within a very short time, and he feels that now is an auspicious time for the campaign to go on." At the moment, Record could claim to have "about $16000 on hand in Ft. Worth, and there are sizeable sums deposited in local banks in San Angelo, El Paso, etc." Record also believed that "the $1,500,000. can be raised in four months time." Ayres then inquired about the status of park measures in the upcoming session of the Texas legislature. Senator Winfield had collaborated with Lieutenant Governor Coke Stevenson to "amplify the bill passed at the last session [1937] authorizing the Texas State Parks Board to buy land in the Big Bend with money raised by the campaign." In addition, Winfield and Stevenson wished to "establish the procedure for transferring the land to the Federal Government for National Park purposes." Record suggested that the park service join in an aggressive publicity effort to "push the campaign now and complete it while the legislature is still in session." Should "any deficiency" result, this could "be met by the legislature . . . (Or possibly by Rockefeller Foundation)." This strategy included review of the measure by NPS officials, and a personal appearance in Austin by Maier to lobby on behalf of Big Bend. [3]

While these details were under negotiation in Austin, Maier learned from Earl A. Trager, chief of the NPS's naturalist division in Washington, that the most famous scientist of the Big Bend country wished to support the park bill in the Lone Star legislature. Robert T. Hill, whose 1899 river trip and subsequent article in Century Magazine had defined the otherworldliness of the Rio Grande canyons for the state and nation, met with Trager at the annual conference of the Geological Society of America to discuss the park initiative. Not only was Hill eager to assist the NPS in its plans for a national park, Trager told Maier, but he "is a bit impatient that things are not moving faster." Trager identified Hill as "one of the earliest geologists who worked in the Southwest and has an enviable reputation in the geological profession." Hill had since retired from teaching, said Trager, "and writes a weekly article for the DALLAS NEWS on matters pertaining to geology." When Hill offered "to do anything he could in his column to promote the project," Trager responded that "we would have you [Maier] advise him of the present status of land acquisition and of the tack he should follow in presenting the project in a feature article." Hill had suggested that "someone should extend the topography from the Big Bend into Mexico because by this method the history of the area is more easily understood." Trager's office had "just completed an attempt along this line," he told Maier, and sent Hill "a set of blue prints for critical review." He then remarked that "Dr. Hill is almost 80 years old and I am sure you will find him an ardent supporter and possessed of a vitality which is not anticipated in a man of his age." Trager closed by noting the degree to which the geological profession respected the work of Hill: "He was one of the five men honored at the 50th anniversary celebration of the Geological Society of America on December 30 [1938]." [4]

As the legislative session commenced in mid-January, NPS attention shifted from publicity to lobbying in the halls of the state capitol. Horace Morelock had asked Everett Townsend to return to Austin to represent the Alpine park promoters. Townsend wasted little time in contacting Senator Winfield and Scott Gaines, whom W.F. Ayres identified as "a former [state] Assistant Attorney General, now connected with the legal department of the University of Texas handling land matters." Gaines "had a good deal to do with preparing the [land-acquisition] bill two years ago," Ayres told Maier; a critical feature since "Senator Winfield is not a lawyer (He is president of the bank at Ft. Stockton)." Winfield had corresponded with Amon Carter regarding the language of the legislation, and Ayres hoped that Maier could join the team of Winfield, Carter, Morelock, Townsend, Gaines, and himself in Austin to prepare the final draft. One reason for organizing such a work session was Ayres's recent conversation with William Lawson of the state parks board. The latter informed Ayres that his agency "would take no part in [the] present legislative effort along Big Bend lines." Ayres admitted that "it is difficult to get at the true feeling of the Board, as Lawson is very jealous of any contact with them other than through him." For his part, Lawson "is not going to do anything that might jeopardize his own Park Board bill;" a phenomenon triggered by the fact that "the Board of Control has already cut it down to [the] approximate level with [Lawson's] present budget, about $40,000." In addition, said Ayres, "the legislature is in a very economical frame of mine." He also noted that "as a rule the Park Board has a more liberal view of things than its secretary." As if these clouds on the legislative horizon were not enough, Ayres heard rumors that "there also appears to be the beginning of a feud between Gov. O'Daniel and Lieut. Gov. Coke Stevenson." Since the latter had championed the Big Bend measure two years earlier, the NPS inspector advised Maier: "It might be well to let Senator Winfield be the principal sponsor this time." [5]

Heightening the sense of urgency facing park sponsors was the inquiry of John N. Harris, Jr., a Dallas attorney representing H.A. Woodruff, a landowner in the future Big Bend National Park. Harris's client had received some 40 acres in Brewster County as a gift from his father-in-law, J.M. Smith. When Woodruff inquired of the county clerk's office about the property taxes for 1939, said Harris, "he was informed that the land was now owned by the state park board." Thus Harris wanted the board to explain "the procedure used in condemning this land, and if possible, the consideration that our client will receive." Chief clerk Will Mann Richardson wrote back to inform Harris that "several years ago when the Big Bend Park was first begun a law was passed conveying to the State Parks Board all lands in the area which were sold for taxes." While "a number of these tracts were foreclosed on and transferred to the State Parks Board," Richardson had to admit that "no accurate record can be found in this office as to what tracts were sold for taxes." Unfortunately, said the board's chief clerk, "we have had several letters from other parties claiming that they still own the land, and that they had never been delinquent in their tax payments." "To such persons," wrote Richardson, "we have replied that there is nothing that we can do at this time to remove the cloud on their title." Instead, "the land will have to be purchased if the Big Bend project goes through, and the Parks Board will probably take notice of their title when purchasing the tract." As an indication of the chaotic state of affairs awaiting NPS and Texas officials, Richardson had to ask Harris if his firm could "investigate and find out whether or not Mr. Woodruff has been delinquent in his taxes." Even if Woodruff had paid his bills, said Richardson, "the only remedy which we know of will be to settle with him at such time as funds are provided for the purchase of Big Bend Park." [6]

By late January the impetus for a new park bill had become clear. Herbert Maier corresponded with James Record to gain a sense of Amon Carter's position on the legislation, asking him to use the 1937 measure as a guide. One feature that local sponsors had suggested was "to call for an appropriation of one thousand dollars so that it may be definitely classed as an appropriation bill." This gave the measure more legitimacy among the Lone Star lawmakers. In addition, said Maier, "a contingency clause is to be included to the effect that the final amount which the State is to appropriate is to be equal to the total sum of money raised by the Big Bend National Park Committee in its forthcoming fund raising campaign." Maier then wrote to Senator Winfield to coordinate plans for introduction of this bill, saying that "it will obviously be best if Mr. Carter, as Chairman of the Committee, signifies his concurrence in the procedure in writing." Maier also commented on discussions had by Winfield and Carter in late December, in which "Mr. Carter was apparently afraid that you or some group might reintroduce last session's bill or rider which was passed by the House and Senate authorizing an appropriation of $750,000." Maier warned that "obviously, if this were to eventuate, it would upset the fund raising campaign." The acting Region III director then summarized the status of his conversations in a report to the NPS director, Arno Cammerer. "I found the matter stymied," wrote Maier, "due to the definite instructions from Amon Carter . . . to the effect that the bill should carry no appropriation." Carter's "insistence that no appropriation be requested of the Legislature is variously interpreted," said Maier. One version had it that Carter "does not wish to place himself under obligations to the new Governor." Others suspected that "he expects to get the money in one lump sum from some donor." Maier informed Cammerer that "Mr. Nelson Rockefeller was mentioned to me in this connection, but I doubt this very much." [7]

Because of the delicate nature of negotiations with state officials, Maier had come to Austin "to get some sort of bill in the hopper at once so as to insure an early number." To his chagrin the acting Region III director "found out that until yesterday, 250 bills had already been given priority." Maier reminded Cammerer that in the 1937 session, "the bill introduced Feb. 23rd could not win, place or show, and the appropriation had to be tacked on at the last minute as a rider to the regular appropriation for the State Parks Board." Hence Maier's screening of the new park bill through James Record. "Amon Carter," said Maier, "is the most powerful man in Texas, [and] must be reckoned with in every move." Maier told Cammerer that "unfortunately he is very busy and is usually inaccessible, and spends much of his time in travel." On a more hopeful note, Maier could state that "certainly this appears to be the most favorable set up we have had on Big Bend Legislation in 3 sessions." Governor O'Daniel, lieutenant governor Coke Stevenson, and Senator Winfield, now a member of the powerful Finance and Banking committees, also championed the legislation. "Rep. [Albert] Cauthorn from the same district [as Winfield] has maneuvered himself onto the House Appropriations Committee for this express purpose," said Maier, while "Chairman [Tom] Beauchamp of the State Parks Board has been named Secretary of State and told me last night he will use his influence to the fullest." Amon Carter had announced that he would invite Director Cammerer to the future park site later that spring, while Governor O'Daniel "has expressed himself likewise." The only caution that Maier had was that "there is nothing new on the fund campaign." He had learned that "there are contracts from three fund raising firms on Mr. Carter's desk, but he has not decided which one he will accept." This latter delay symbolized to Maier the problems facing the NPS in their efforts to create Big Bend National Park, and he concluded to Cammerer: "I do wish this angle of the thing were less of a mystery." [8]

The irony of Maier's remark was that "mystery" had defined the promotional literature supplied to local park promoters by NPS publicists for much of the 1930s. The most erudite voice of Big Bend's otherworldliness, Walter Prescott Webb, visited Fort Worth in January of 1939, and granted an interview to the Star Telegram. In a story syndicated statewide, Amon Carter's editors quoted Webb as saying: "The palpitating beauty and the varying effects of sunshine, rain, and passing clouds make the Big Bend a 'mysterious, wild country with a peculiar effect on those fortunate enough to visit there.'" Echoing much of his earlier writing about the future national park, Webb recalled for the Star Telegram's readers "his first visit to the Big Bend in a Model T Ford in the Summer of 1924." Webb asked rhetorically: "'I don't see why more people don't go there,'" as Big Bend offered "'something for everyone - the natural scientists, anthropologists, historians and especially the general public.'" This rendered Big Bend "'a veritable museum,'" said the dean of Texas historians, as "'the land has little economic value.'" Yet "'Mexico is ready to add an even larger parcel of land to the proposed park,'" Webb told the Star Telegram, and "'the resulting international park would be a strong factor for peace in a world where most countries feel they must maintain a strong guard around their borders.'" He recalled how he had looked at the sunset over the Sierra del Carmen, seeing in silhouette "a massive human form outstretched in perfect repose, feet 30 miles from head, hands folded over chest, good chin, straight nose and fine brow." This likeness the Texas Rangers had called "the War God of the Rio Grande." Now that global conflict loomed once more on the international horizon, Webb told readers of Texas newspapers carrying the Star Telegram interview: "'The whole effect, as we sat under a million stars, the silence broken by coyotes yip-yapping to each other from distant hills, was not that of war, but of tranquility and peace.'" The University of Texas scholar then concluded that "Texans should make every effort to acquire the land for the park." [9]

To the authors of Senate Bill 123, however, the quest for funding for Big Bend National Park was no mystery. They knew exactly the conditions of politics and economics that they faced when H.L. Winfield and Albert Cauthorn stood before their colleagues in the Austin state capitol on January 31 and asked them to endorse the plan for private purchase of the acreage needed. The NPS's W.F. Ayres and Ross Maxwell had read the bill, noting that boundary adjustments had been made to the 1937 measure. "You will notice," said Ayres in correspondence to Maier, that "the first 'call' runs straight to Sue Peaks from the monument we set two years ago." The state parks board would be "the agency to carry out the provisions of this act," while "school lands are to be withdrawn for sale, and the surface rights sold to the State for park purposes at $1.00 per acre." As for the hotly contested mineral rights, these "are to be sold to the State . . . at 50 [cents] per acre." Ayres predicted that "we will no doubt run into a battle with the Texas State Teachers Assn. on this; yet we must try to get these rights and let Legislature settle the question." Winfield and Cauthorn included a provision whereby "the Texas State Parks Board is authorized to exchange lands which they hold outside the park area for lands inside," while the board would offer "purchase limited to $2.00 per acre on voluntary sales paid from appropriated funds." Finally, the west Texas lawmakers asked their colleagues for the nominal sum of $1,000 to initiate this program, and granted to the governor the right to "convey to the United States" title to all lands purchased for the park. Perhaps the best news forwarded by Ayres to regional headquarters was that Amon Carter had read the contents of Herbert Maier's memorandum on the Winfield/Cauthorn bill, and "was in complete accord with it." Ayres concluded that Carter was "anxious to proceed as outlined," and saw hope for the champions of Big Bend as the legislature contemplated the park's destiny. [10]

Within days of the bill's introduction, park sponsors in Washington, Santa Fe, Austin and Alpine circulated press releases touting the benefits to accrue to Lone Star citizens once their elected representatives approved of the land-acquisition program. No less a personage than Elliott Roosevelt, son of the president, called in a national radio broadcast for passage of Texas Senate Bill 123. Reading from copy provided by the NPS, the younger Roosevelt claimed that Big Bend would be "commercially beneficial to every section of Texas." Reiterating the mathematical model of five days of travel within the Lone Star state by the average tourist, Elliott Roosevelt declared that "the State will profit by new, improved highways built with money derived from gasoline taxes which the tourists will pay." Texans also would gain, in the estimation of the president's son, "an advertising medium [that] alone would be worth thousands of dollars . . . in drawing new industries and permanent residents, as well as tourists, to the State." For Texans "with limited means and short vacation periods," Big Bend offered "the scenic wonders of a national park without having to journey out of state." Elliott Roosevelt also suggested that the new park "would provide a place near by for the Texas business man to enjoy weekend outings without the loss of time and money that it would take for him to go out of the State." He predicted easy passage of the legislation in the Texas senate, even with the opposition of the state's school teachers, as "the additional revenue which would go into the school fund from the sale of gasoline to state visitors who would come to see the park would more than equal the board's present income from the land." Roosevelt then concluded that "the popular subscription drive will be one of the most gigantic demonstrations of concerted effort ever seen in Texas." [11]

Another, more curious promotional angle about Big Bend came from J. Frank Dobie, whom the Pampa News said had "run out on English classes he teaches in the University of Texas to 'hole up' in the [Chisos] mountains here while he works on his next book, 'Texas Longhorns.'" Dobie told an interviewer that he had come to the abandoned CCC camp in the Chisos Mountains "to spend some six weeks working on his book, which is to be a comprehensive history of the development of the Longhorns from the time the first Spanish cattle were unloaded on the island of Sant[o] Domingo by Columbus on his second voyage to America." The Texas folklorist had sought in the Big Bend remnants of the longhorn breeds that he knew as a youth on his family's ranch in the Live Oak country. Those animals, Dobie told the Pampa News, "would lift sand upon their backs and necks with their fore feet, bellowing constantly." After "working themselves into the proper mood for battle," the longhorns "would lower their heads and charge, and acres of brush would be trampled before one bull succeeded in goring to death or whipping out the other." This Dobie called "'a grand spectacle,'" and one that he hoped to witness while in the future national park. He then remarked to the Pampa reporter on the distinctive features of life in the former CCC camp. "To clear his mind between working hours," said the reporter, "Dobie chops stove wood or explores the wild mountain peaks about him, sometimes accompanied by the only other occupant of the camp, Custodian Lloyd Wade." [12]

Yet a third news story spawned by the media campaign surrounding Senate Bill 123 was more worrisome to Herbert Maier and his NPS colleagues. The local newspaper in Fort Stockton reported that Senator Winfield had "announced that definite assurance had been received from a scientific foundation that it would donate $1,000,000 for the Big Bend National Park project." Maier quickly contacted Everett Townsend for advice, noting that "I do not think that Senator Winfield would give out such a statement in his home paper unless the statement had a sound basis in fact." "Naturally," Maier cautioned, "we are very much interested in this statement since we, like others, have wondered about the delay in getting the fund raising campaign under way." Maier realized that "Mr. Carter was flirting with various foundations," and asked if Townsend could "look into this and drop us a line at the earliest moment?" [13]

While Maier awaited word from Townsend about Winfield's claim of a million-dollar donor for Big Bend, the Texas state parks board registered some surprise late in February when the new Region III director, Hillory Tolson, wrote to William Lawson about other potential NPS sites in Texas. "We, of course," responded chief clerk Will Mann Richardson, "have no objection to Palo Duro Canyon becoming a National Park." Yet the parks board warned Tolson that "we should call to your attention one or two facts in regard to the area" south of Amarillo. "In the first place," said Richardson, "we do not believe it will be possible to get the Legislature to appropriate money to purchase this land now when we are trying to get the Big Bend area purchased for a National Park." Another concern for the parks board, said its chief clerk, was that "it would take an Act of the Legislature to transfer whatever interest the State may have in the area to the National Park Service." Even if the Lone Star lawmakers agreed, "we would hate to transfer to anyone the obligation, which we now have, to pay a grossly exorbitant price for the [Palo Duro] property." Richardson contended that "the indebtedness against the land at the present time is around one-half million dollars and out of all proportion to the value of the property." He then warned Tolson: "If the landowners are going to insist on such a valuation being placed on the property we feel that you should be aware of this fact before anything further is done." [14]

Within days of Tolson's inquiry about NPS status for Palo Duro Canyon, Will Mann Richardson contacted W.F. Ayres with news that Governor O'Daniel, in the words of Herbert Maier, "is planning to introduce a bill for conveying the Big Bend land to the Federal Government, and, apparently, will include in the bill a request for a large appropriation for land purchase." Maier worried that "this second bill, if introduced, will confuse the situation." He then advised Ayres "that apparently State Park Chairman Lawson, who is now Acting Secretary for the Governor, and Secretary of State Beauchamp may have advised the Governor to introduce his own bill so as to 'steal the show' from Amon Carter." Maier speculated that "the Governor may, however, be ignorant of the fact that a Big Bend bill was already introduced a month ago by Senator Winfield." Since "we do not know what has prompted the Governor's action," said Maier, "I advised Ayres that . . . he should not contact Lawson or the Governor, but should immediately contact Senator Winfield and Representative Cauthorn, and have them size up the situation and report to this Office by air mail." The associate regional director surmised that "if the Governor's bill calls for a large appropriation, and if it comes up about the time the fund-raising campaign is under way, the public may become confused and private subscriptions discouraged." This realization came just as the NPS had completed a "relief model of the Big Bend area made at Fort Hunt." Maier had received permission to display the model at the Texas state capitol, but complained that "the map was not painted in realistic colors but in a monotone, and this is certainly unfortunate," as well as the map itself being assembled in two pieces, "which is further unfortunate." [15]

O'Daniel's rumored intervention forced NPS officials and park sponsors to assemble in Austin, where they converged on the office of Secretary of State Tom Beauchamp. Once there, NPS inspector Ayres learned that the governor merely planned "to send up a message to the legislature endorsing the Big Bend Park movement in general." Senate Bill No. 123 had been reported out of the finance committee, but Senator Winfield still awaited the "action of Amon Carter and the executive committee." One concern for Ayres was "that the legislature is deadlocked on this old age pension business, and its attendant Transaction Tax." Yet Ayres could report to Maier that "both Winfield and Cauthorn feel confident that a substantial appropriation bill could be passed, and if the Carter faction don't act pretty soon they may introduce an amendment to this bill carrying a big appropriation." Winfield also indicated to Ayres that "the Senate at least will retain the 'mineral rights' clause, and convince the School Lobby that they will get more from their share of the gasoline tax (1 cent per gallon) on the increased travel than they ever would from developed minerals in the area." Ayres also had been able to inquire of Winfield the significance of his remarks to the San Angelo Times about the "'definite assurance'" of a million-dollar donation to the Big Bend campaign. Winfield had meant "merely a 'possibility,'" Ayres told Maier. Yet "of course this kind of publicity is bad for a public subscription campaign," said the NPS inspector, noting also that "there are a surprisingly large number of people who feel that it would be much better and easier to have the legislature appropriate the funds." [16]

True to his word, Governor O'Daniel sent to the state house and senate on March 1 his message in favor of the Big Bend land-acquisition program. He wished to point out "a few interesting facts concerning this great 'GIFT OF GOD' to Texas and to our Nation." O'Daniel further wanted to "declare that an emergency exists and that great loss may accrue to our people unless immediate action is taken on the pending bill." Speaking lyrically of the beauty and grandeur of the future national park, O'Daniel told the state's lawmakers that the Chisos Mountains "have been described as the most rugged mountains in the world, wherein we find deep gorges and cliffs and mile-high peaks dyed in deep mineral coloring and dressed with nature's most wonderful blanket of trees, vines and grasses." The governor, himself a visitor to the Chisos, claimed that "from many large peaks the gorgeous scenery is as impressive as a vast fairy land." Saving special praise for the South Rim, O'Daniel claimed that "from high mountain cliffs we may look down upon a landscape . . . which has been proclaimed by many as the most gorgeous on the continent." The Chisos in particular, said the governor, "have become the garden for a most unusual plant life comprising a variety of nearly one thousand species." They constituted what O'Daniel called "both a vegetable island and an animal island," as scientists "find here life of both in abundance which is strange to the country around for hundreds of miles away." Among these was an "oyster shell thirty six inches in diameter." Big Bend's cultural and historical resources also rendered the landscape worthy of NPS protection, said the governor. "The word Chisos means 'Ghost,'" O'Daniel intoned, "and it was believed that in the early days the ghost of many who ventured the climb into them constituted the strange inhabitants." He also spoke of the archaeological surveys undertaken by Harvard University and Sul Ross State Teachers College, with the conclusion of one "eminent geologist . . . that the grandsons of the geologist of today will not have completed the lesson which they are now studying in this great classroom." [17]

In order to convince the Texas legislators of the merits of Big Bend, O'Daniel recited the by-now familiar economic data of tourist expenditures and ancillary benefits from increased tax revenues. "I have been informed," said the governor, "that many parks have been offered to the National Government for National Parks, but this Big Bend areas is perhaps the last important area which the National Park Department so strongly desires." He then highlighted the "talk of Mexico setting aside one million acres directly across the Rio Grande." This gesture would make "an International Park, unequalled anywhere else on earth, and a strong influence toward the 'Good Neighbor' policy." O'Daniel closed his plea to the legislature by reading from a letter written by President Franklin Roosevelt. "'As you may know,'" said FDR, "'I am very much interested in the proposed Big Bend National Park in your State.'" The president had "been hoping that this Park could be dedicated during my Administration." Roosevelt thus requested of O'Daniel that "'this large and very interesting area could be bought for a comparatively small sum--a sum that would be insignificant in comparison with the economic return that would follow to the State of Texas and to the Nation, from every point of view.'" FDR then summarized his appeal to the Texas governor: "If the Texas legislature at this session should see fit to make an appropriation for the acquisition of this land, it would be very gratifying to me personally, and I am sure that it would win the general approval of people everywhere.'" [18]

With the endorsement of Franklin Roosevelt, and the enthusiastic support of the governor, park sponsors began to imagine a grander scenario in which they appealed to the Texas legislature for a substantial sum of money. Inspector Ayres filed daily reports with NPS officials in Santa Fe to offer them a sense of the momentum building among Lone Star lawmakers for the land-acquisition program. On March 4, Ayres informed his superiors that "there is the feeling, which I share, that now is a very good time to insert a clause raising the appropriation to $750,000." The more controversial measures awaiting legislative action had yet to be addressed, and "I am afraid if we wait too long," said the NPS inspector, "the bill may get involved in the general fight, and get slugged as an economy gesture by tax opponents." Ayres learned from capitol insiders that "the legislature could start the movement with this amount, and public subscription, private foundation[,] etc[.] could supplement the funds." Should park sponsors not prevail in their donation campaign, "this is all the money the [parks] board could spend for land in the next two years, and then they could get the balance from the next legislature." Most surprising was the consensus, as reported by Ayres, that "in any event it looks as though they may not wait for Amon Carter, since we are in the third month of a four month session, and pass the bill anyway." [19]

Sentiment for avoiding the dilatory tactics displayed by Amon Carter faded as the NPS realized the importance of the Fort Worth Star Telegram to their efforts at publicity for Big Bend. Thus Hillory Tolson wrote on March 7 to Carter to seek his advice on the language contained in the land-acquisition bill. The park service agreed in principle with the objectives of Winfield and Cauthorn, offering only two suggested changes. The first requested that the document read: "Which a sales tax is levied in this State, and to tax persons and corporations, their franchises and properties, on land or lands deeded . . . ." More substantial, in the minds of Tolson and his superiors, was the need to delete a sentence that "provides for the free admission of all school children under eighteen years of age." The NPS counsel ruled that "the inclusion of this sentence would present an administrative limitation by the State on the exercise of Federal authority over the area after it becomes a national park." Tolson reminded Carter that "an admission charge as such is not being charged nor is any contemplated in any of the national parks." He admitted: "It is true that a guide fee is charged at Carlsbad Caverns National Park, but groups of school children under 16 years of age are admitted without charge when accompanied by an adult teacher, upon payment of the regular fee by that teacher." Tolson suggested that Carter encourage the removal of the sentence on fees, in order that NPS officials not raise "a serious technical objection." [20]

Whatever the language of the Big Bend park bill, word circulated by mid-March of problems with its passage. Herbert Maier learned from Conrad Wirth that officials from the El Paso chamber of commerce had informed him that "Governor O'Daniel is having a great deal of difficulty in getting the Big Bend bill through the legislature." Maier indicated to NPS personnel in Austin that "some definite urging by way of a strong letter to the Governor, on the part of the Secretary of the Interior, appeared advisable at this time." Maier himself had no evidence of "any real difficulty" confronting the park bill, with both house and senate committees reporting favorably on its contents and "a great many newspaper clippings" generated by the publicity campaign. Nonetheless, Maier did acknowledge that "the Governor is having much opposition in getting many of his proposals through," and that "some legislators will call attention to the likelihood that the $1,000 appropriation called for may be many times increased before final action on the bill is consummated." Wirth's suggestion that Harold Ickes endorse the park measure concerned Maier, given the highly publicized letter from FDR. Some in the Texas capital might perceive this strategy "as excessive pressure on the part of the Government, since the acquiring of large blocks of land by the Federal Government is very much of a new idea in Texas." Thus Maier solicited the opinion of Amon Carter, asking James Record to "obtain information and advice from him as to the exact status of the bill, and its chances for passage, and as to whether the proposed letter from either the Secretary of the Interior or the Director of the National Park Service would be the advisable thing to do." [21]

Maier and the Big Bend sponsors expressed relief that Texas lawmakers had not singled out their measure for particular criticism. The park bill's advocates maintained their vigil in Austin, working with Senator Winfield and Representative Cauthorn to assess the temper of the legislature. The former told W.F. Ayres that "the Senate was in an ugly mood provoked by discussion of the very controversial budget bill." Lieutenant Governor Stevenson advised Winfield "to wait for the proper opening when the members were in a better frame of mind generally." Everett Townsend sought out the opinion of a former legislator, Judge Walter E. Jones, identified by Townsend as "probably the best informed man in Austin on just what is going on in the legislature." Jones dismissed fears about the lawmakers' state of mind, reminding Townsend that "no bill of importance has passed either house." He predicted "no serious trouble ahead," and "advised to leave well enough alone." All parties consulted by park sponsors counseled against intervention by NPS officials from Washington, yet the state parks board's Richardson noted that "the younger House members from East Texas . . . are for the Big Bend bill, but are going to try to hang on an amendment providing for establishment of the Big Thicket also as a National Park." Given the interest growing in the state for national park units, L.C. Fuller, state supervisor of recreation studies for the NPS, suggested to Maier that "a telegram from the Secretary or the Director should be prepared and held in readiness for dispatch to the Governor at the proper time." He then closed his "confidential" memorandum to Maier by noting the attitude expressed by Townsend, "who thinks the bill will pass but has recently placed added emphasis on the word 'dam' which always precedes the word 'schoolteachers' in his conversation." [22]

Despite these obstacles, sponsors of Big Bend National Park persevered in their lobbying efforts throughout the spring of 1939. By April 28, the Texas State Representatives had voted 23 to 2 in favor of the measure, and sent it over to the state senate. Conrad Wirth kept NPS director Cammerer apprised of the Big Bend legislation, informing him that "the bill calls for an appropriation of only $1,000." This Wirth believed "is included merely to give it the status of an appropriation bill," and "the amount can be increased indefinitely in committee in order to make up any deficit in the [fundraising] campaign." This latter initiative still concerned Wirth, who had asked Herbert Maier to "furnish a report on the progress." Wirth then reminded Cammerer of the significance of FDR's personal endorsement of Big Bend to Governor O'Daniel, and of Interior Secretary Ickes's request to Vice President John Nance Garner to do likewise, but "so far the Vice President has not indicated what action he will take." Yet the newspapers of Texas found the state house's actions reassuring, as the Dallas News of April 30 reminded its readers: "With many families already planning summer trips, it is not too early to point out some of the advantages of vacations in Texas." "If one is not hardy enough for the still undeveloped wilds of the Big Bend," said the News's editors, "there are attractive dude ranches in the Davis Mountains and fishing and bathing resorts on the Gulf coast." The Dallas News noted how "with help from the Civilian Conservation Corps, the state parks of Texas have undergone a surprising transformation in the last six years." The CCC had expanded recreational sites, "and accommodations have been provided for picnickers and overnight visitors." Big Bend National Park would become part of this outdoor experience, said the News, and "despite the lure of far-off places, it will pay to see Texas first." [23]

While Texans contemplated a visit to their future national park on the Rio Grande, and lawmakers in Austin prepared to pass a bill making that more of a reality than ever, the fundraising campaign continued to lag. A telling example of the caution exercised by Amon Carter and the park sponsors came on May 3, when Adrian Wychgel of New York City wrote to Arno Cammerer about receiving a copy of the NPS booklet promoting Big Bend. "It was awfully good of you to place my name on your mailing list," said Wychgel, "and I appreciate this courtesy." Whether Wychgel was sincere or cynical, he told Cammerer: "I am still urging the Committee in Texas to get started on the money-raising effort." Wychgel had been informed by "Mr. Carter and his associates . . . that when the time is right, that my services will be retained in connection with the fund-raising endeavor." Yet the New York consultant was "fearful, to speak very confidentially to you, that like all matters of this kind, the committee is just putting off from month to month." Wychgel had heard of the imminent passage of legislation in Austin, a move that he considered "in the right direction." Yet "the matter of interesting the public and engaging their attention should not be delayed any longer." Sounding as if he saw little chance for his firm to bid on the fundraising contract, Wychgel advised Cammerer: "Knowing how interested you are in seeing the Big Bend Project become a National Park, I am just wondering if there is anything you could do to urge the Committee to immediate action." [24]

Wychgel's anxiety had some basis in fact, even when the Texas state senate on May 12 passed and sent to the governor the Big Bend measure. The Houston Chronicle carried a statement from Amon Carter that "passage . . . of the Big Bend Park bill and signing of the same by Governor O'Daniel did not mean that the park is now an accomplished fact, or even near an accomplished fact." Carter told the Chronicle that "the real work is now before us," the raising of some $1.5 million to acquire land "which the bill gives us the authority to buy and to present to the National Park Service." The Star Telegram publisher noted that "this bill is only enabling legislation." He then outlined the steps to be taken by the "Texas Big Bend Park Association," with a "'working fund'" that still required "'that all subscribers . . . complete their quotas so that the state-wide campaign can begin.'" Carter declared that tourism in 1938 had generated some $45 million in Texas, and that "a national park will double and treble this sum the first year." He also cautioned readers of the Chronicle that "'the impression gained circulation that the recent action of the legislature in passing the enabling bill has been the final step toward establishment of the park.'" Carter instead declared that "the purpose of this statement . . . is to correct this wrong impression and to let the public know that the fate of the park is now in the hands of Texas as a whole.'" Once Lone Star citizens contributed to the fund, said Carter, "'we hope to complete the campaign in short order, as we want to dedicate the park during the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Vice President John N. Garner.'" [25]

As with so much of the promotion of Big Bend, NPS officials confided in each other of the challenges facing the private solicitation of funds in Texas. At the signing ceremony in the governor's office, O'Daniel broke precedent by using four pens of 42 inches in length each. "Anything as Big as Big Bend Calls for Use of Big Pen," read the headline of May 14 in the Fort Worth Star Telegram. Herbert Maier then provided Arno Cammerer with details of the bill's passage, and of the journey awaiting park sponsors as Amon Carter initiated the fundraising project. "The school fund must now part with its mineral rights," Maier told the NPS director, and that "it will be noted therefrom that all items requested by the Washington Office were incorporated." The original request for $1,000 "had to finally be stricken out to satisfy a group in the House who were pledged to vote against all appropriation bills." Maier then reported that "there are several reasons why this campaign has not gotten underway and some of these no doubt involve personal jealousies." "Certain committee members," said the associate regional director, "have not yet made good on their personal pledges for the initial $25,000 publicity fund." James Record had told Maier that delay resulted in part because "the European situation since last fall has kept big business in Texas so tightened that it would have been impossible to shake loose a million dollars." In addition, said Maier, "if the Bill had failed of passage, the fundraising campaign would have likewise failed with the result that the National Park Project would be a dead issue for years to come." Once the Texas lawmakers endorsed the concept of a national park, "the school land obstructions have now been removed and with the current improvement in business in the State, Mr. Carter feels the time is propitious." Maier acknowledged that "the campaign will apparently be carried on over a rather lengthy period," comprised of "a local committee in each of the 254 counties with a fixed quota for each." The fundraising venues included "a benefit football game next fall" that might raise a total of $250,000, "and there are other schemes for raising money." Should the campaign falter, said Maier, "the balance, it is planned, will be called for through State appropriation at a special session of the Legislature next spring." The committee also would begin the actual purchasing of land "as soon as $100,000 is at hand." Maier predicted that "it will require from two to three years to acquire all the land," but closed on a note of optimism not seen since mid-decade: "It would appear, however, [that] the development work in the area through the CCC can be safely resumed before that time." [26]

Simultaneous with the announcement of passage of the Big Bend legislation, the park service benefited from publicity generated by a river trip through the Rio Grande canyons by Milton F. Hill of Marfa, Texas. Much as in 1937, when Walter Prescott Webb navigated the rapids of Santa Elena Canyon, Hill and five others first ventured through the same canyon in mid-April. Aided by CCC camp custodian Lloyd Wade, the Hill party also had assistance from the U.S. Army post at Fort D.A. Russell. The NPS contacted the Associated Press news service in Texas with word of the Hill venture, resulting in what Herbert Maier told Hill were many news clips. "The descriptions of Fern Canyon," said Maier, "are particularly interesting and of value," and he requested that Hill inform the park service when the latter planned his voyage through Mariscal Canyon, "so that we may more successfully arrange the matter of supplying you with film on the basis of the arrangement discussed with you by the undersigned [Maier] at Marfa." Not until June did Milton Hill, his son Milton, Junior, and his son's friend Harvey Smith take the journey through Mariscal Canyon, but his description made headlines in newspapers throughout Texas. While "the walls here did not impress me as being quite as high as the S.H. [Santa Helena] walls," said the elder Hill, "the scenery is very beautiful in here, the walls gradually getting higher." He recalled that "some magnificent pinnacles and great rock towers are in here, and the final part of the gorge has very precipitous walls." [27]

As the Hill party neared their overnight destination of the Hot Springs, they encountered a swift channel but "had no trouble navigating it." Milton Hill judged Mariscal Canyon "not a difficult or dangerous trip at all in ordinary water, and has no place in it even approaching the Labrynth in difficulty." He estimated that "if there were a good place to get to the river and a place to get out good boatmen could take tourists through there with no trouble at all right now." Hill then remarked on the "fine scenery for several miles below the canyon." As they passed "the end of the San Vicente [Mountains] in Mexico," which Hill described as "a high and rugged range," they entered "the San Vicente Canyon, with vertical walls about 400 feet high." The Marfa minister declared that "it would have great fame east of the Mississippi [River] if the other canyons did not overtop it." A mile below San Vicente, Hill and his party encountered "a remarkable cream-colored cliff on the Texas side." There they saw "many sculptured hills of thin-bedded limestone, magnificent views of the Chisos and the [Sierra] Del Carmen." At this point they spotted "two beavers swimming in the high water, and in the Mariscal are numerous big blue herons." Hill remarked that "the main difficulty in making the [Mariscal] canyon now is getting to the river." The party had to carry their boats one-half mile over rough terrain. "However," said Hill, "it might be possible to get closer by going up-stream a little further," where "boats could be taken out at the Solis ranch . . . and thus avoid the long trip to Hot Springs." Hill extended his thanks to Lloyd Wade, as "the trip would have been impossible without his cooperation," as well as the hospitality of Mrs. J.O. Langford, who along with her husband managed the facilities at the Hot Springs. Hill then concluded that "if our people knew what they have in that Big Bend section in the way of scenery and health-giving wilderness they would surely make it a Park and visit it." [28]

The attention paid by the Texas media to Milton Hill's navigation of the canyons of the Rio Grande inspired others to attempt similar ventures. The most prominent of these involved Roy Swift, the youthful editor of the Robstown Record. The twenty-seven-year old Swift, joined by his 37-year old brother W.E. Swift, opted to swim the 20 miles from Lajitas through Santa Elena Canyon, a feat that had led in 1938 to the death of a Fort D.A. Russell soldier using an inner tube. The Swift brothers themselves had floated halfway through the canyon in 1931, and a year later had explored the large opening known as the "Great Cave," some 150 feet in diameter located high on the canyon walls. The Corpus Christi Caller-Times also reported that W.E. Swift had been "a member of a party that climbed the face of a cliff deep in the canyon to photograph the gorge from above." The Swifts' successful journey through Santa Elena Canyon had taken them thirteen hours, said the Albuquerque Journal, with the brothers "wearing swimming suits, heavy hats, knee pads and tennis shoes." Ten miles into the canyon they confronted walls that rose between 1,000 and 2,000 feet from the river's edge. Then two miles further downstream, said Roy Swift, "'we encountered the dangerous rapids where several boats and lives have been lost.'" They saw "'boulders strewn in the river [that] made it look to us impossible that any boat could get through.'" The Swifts also struggled with "places along this quarter-mile stretch in which no swimmer could live and we used ropes to get over and around the boulders.'" [29]

Publicity continued to emanate from the sponsors of Big Bend National Park in the spring and summer, as they sought to sustain the momentum of the 1939 Texas legislative session, and to create a sense of inevitability about the fundraising campaign. In late May, H.W. Kier, a filmmaker from San Antonio, met with Everett Townsend to plan a script for a newsreel on the Big Bend. Relying heavily on the dramatic themes made popular by Walter Prescott Webb, and lionized in Hollywood westerns of the 1930s, Kier claimed that "the frontier of half a century ago, still lingers untouched by the progress that has passed it by unheeding." Kier described Santiago Range as named for "a soldier of old Spain killed in an attack against the redskins on the northern slopes of the peak." He paid special attention to "the haze hidden peaks of the mighty [Chisos] Mountains," whose name "is Apache for Ghostly." The Chisos "in the distance," said the San Antonio filmmaker, "seem unreal, almost detached from the earth . . . grim . . . silent." Huarache Spring (spelled "Hurrache" by Kier) had earned its name as a place "where the first white man to enter this region found a pair of rawhide sandals [huaraches] left by some Indian." He identified "Dog Canyon" as "perpendicular cliffs . . . lined with caves that were once the homes of a pack of wild dogs that played havoc with the herds of the first settlers in this part of the 'Bend.'" Kier then came upon "an ex-college professor and the members of his family," whom the filmmaker claimed "used a loom that is an adaptation of the old Apache hand-loom." This permitted the unnamed professor to "weave Boquillos rugs from native mohair." Kier described this work as "skillfully and interestingly done," with "the pattern, designs and color, all original and done by hand beneath an outdoor arbor." [30]

Reaching the river's edge, Kier's film crew shot footage of the "ancient bathing place of Hot Springs," which he stated "serves the visiting whites as it once served the Warriors of the raiding Commanches." These Indians, "returning from their forays into Mexico," said Kier, "halted here long enough to bathe in the health-giving waters." "Today," Kier noted dryly, "semi modern conveniences await the visitors." Then the film crew came upon the village of Boquillas, Texas, where "Maria Sada and her family offer the hospitality of Old Spain . . . with a charm and courtesy that is distinctly of the old world." Maria Sada, known locally as "Chata," served "visitors with food prepared in the distinctive style of 'Big Bend,'" as Kier claimed that "her family has lived in this region for nearly 200 years." Across the river in Mexico, Kier found "the remains of Boquillos [sic], once a prosperous mining town . . . now almost deserted." The Mexican village known as Boquillas was "slowly crumbling from ruin and neglect." Further upstream the crew paused at San Vicente, which Kier described as "old . . . just how old no one knows." The site was "all that is left of the village that grew up beside the ancient Presidio de San Vicente, built in 1770 to guard the Commanche War Trail." Kier claimed that "some of the houses are the original ones and show the ancient hand-hewn beams and sills," while "the old methods of planting and harvesting still prevail in the little fields beside the river." He then recounted the story "that the monks of the mission that stood beside the Presidio worked a gold mine some where in the Chisos Mountains;" hence the famed "Lost Mine Peak," where "prospectors still search for the old shaft from which came the mission gold." [31]

Once the film crew had finished their shooting in Boquillas, they turned back west to Glenn Springs. This Kier described as "a green garden spot at the foothills of the pink and red parapets of the 10,000 foot Carmen Mountains . . . in Old Mexico." The crew passed "Johnson Ranch with hotel accommodations and landing field," eventually reaching Castolon, "lying in the shelter of the great pink mountain that is called Castolon Peak." There the crew filmed what they called "the Grand Canyon of the Rio Grande," where "many lives have been lost in attempting the passage of the wild rocky miles of twisted Canyon." The 2,000-feet-high barrier "almost shuts out the light of day," said Kier, and "the roar of the water fills the space between the narrow walls with a noise so constant, so profound . . . that [it] is almost a silence." Venturing northward from the Rio Grande, Kier's crew reached Terlingua, identified as a place where "primitive mining conditions prevail in one of the largest quicksilver mines in the country." The crew filmed a scene where "the homes and graveyards of the miners bespeak their frontier lack of anything that resembles modern comforts." Eastward the crew drove until they turned south through Green Gulch. There they found "CCC Camps that built the road and marked many of the trails into still more rugged vastness of the higher ridges." In the Basin Kier found "broad views sweeping for miles over a terrain as rugged and wild, as primitive and untouched as when white men first viewed it." Kier's crew then retraced their route northward to the base of the Chisos Mountains, and closed with the statement: "The mystery of the 'Big Bend' is a mystery no longer." "That which was once an impenetrable wilderness," said Kier, "is now the playground of the people of Texas and their friends and visitors from everywhere." Kier then left the potential viewer with the heartening thought: "Here, to-day meets yesterday in the heart of a mountain wonderland." [32]

Kier's script revealed once more the problem that the NPS faced in crafting a story that dramatized the otherworldliness of Big Bend, while assuring urban audiences that the ruggedness of the terrain meant them little harm. Katharine Seymour, a writer from San Antonio, had gone to the Big Bend area in late May to research a story on the future national park. Seymour had visited with Ross Maxwell at the NPS's Austin office, describing the park service geologist as "another Big Bend addict." Her use of NPS files led her to ask Herbert Maier: "I want to do a book on the whole International Park area. What do you think about it?" Seymour also noted the assistance given her by Lloyd Wade of the Chisos CCC camp. "Apparently he wanted me to get the real stuff," she told Maier, "for his complaint about writers in general is that 'they always write about the country like it used to be and it never was that way.'" Upon reflection, said Seymour, "I am inclined to agree with him." She was working on the West Texas section of a book on the State of Texas, a collaboration job with J.H. Plenn, author of Mexico Marches, published in March 1939 by Bobbs-Merrill Company. Seymour's exposure to the Big Bend had inspired her to write an in-depth study of the area, even though "the hitch is in being financially able to carry the Park book through [to publication]." Should the NPS agree to support her work, Seymour thought that "Mr. Wade's help would be the best we could possibly have in covering the park area, for I realized in talking over this west Texas material with him, that he has a more intelligent and intelligible slant on the country than anybody else who might be available to us for that service." Wade also "has the added quality of allowing people to think for themselves occasionally instead of distorting their vision and sickening their ears with picaresque anecdotes -- if you know what I mean." Seymour came away from her visit convinced that Big Bend was "my favorite subject," and she promised Maier to "be as honest as possible without making it too hot for the publisher to handle. After all this is the Big Bend we are talking about." [33]

Maier found Seymour's correspondence intriguing, given the need for as much good news as the NPS could generate. Thus he responded to her inquiry: "It is the policy of the National Park Service to assist wherever possible, to the extent permissible under regulations, in the writing of books and articles that will give favorable publicity to National Park Service areas." Unfortunately, said Maier: "With the exception of the CCC Camp, this Service at present has no jurisdiction over the area." He also cautioned Seymour about the ability of Lloyd Wade to assist her research. Wade, said Maier, "is the only one employed by the National Park Service now in this area." As caretaker, "the regulations require that he be on duty at the camp 24 hours each day;" a circumstance that was "largely in the interest of fire prevention." The NPS had "furnished [Wade] with a Government pick-up truck; however, regulations do not permit the use of a Government car for other than official transportation." Maier did agree that Wade could "assist you in any manner that does not conflict with the limitations that have been imposed on CCC camp caretakers." The acting Region III director had done so because "your plan for writing a book on the Big Bend area that will include archaeology, geology, fauna, flora, etc., we feel, will be a very worthwhile undertaking." Maier acknowledged that "National Park areas are made up of these scientific elements, and national park tourists are eager for a popular interpretation, especially in an area such as the Big Bend in which the visitor will always be conscious of the presence of these elements and eager for their interpretation." [34]

For readers of news stories about the future national park, little information appeared regarding the status of land sales and ownership in Brewster County; this a result of the uncertainty surrounding when (or if) the state parks board would commence acquisition proceedings. Nonetheless, A.M. Turney, county attorney for Brewster County, discovered in July what Everett Townsend had learned four years earlier when he surveyed land ownership patterns in the Big Bend area. Writing to Wendell Mayes, Turney reported that "the Tax Assessor and the County Clerk of this Brewster County, Texas, inform me that they do not have a list of the lands owned by the Park Board of Texas." Turney also had found that "there have been over 300 delinquent tax suits filed in this County and a great many of them in the lower end of the County, and the Deputy Tax Assessor and Collector tells me that he believes that the suits probably are on a good deal of lands owned by the Park Board." In order to prepare for potential land purchases, Turney asked Mayes: "I would like to have a list of all of the land owned by the Park Board situated in this County, . . . in order that I may not take judgment for taxes on this land." [35]

Little did A.M. Turney or anyone else involved with the promotion of Big Bend National Park realize how their lives (and the prospects for land acquisition) would change when on September 1 the armed forces of Germany instigated the Second World War. Within two weeks of the "blitzkrieg" strike of Hitler's "Wehrmact" against the helpless people of Poland, the Fort Worth Star Telegram carried an editorial with the curious title, "Tourist Opportunity." "Out of the wreckage of the tourist business in Europe," said the Fort Worth paper, "for the rebuilding of which years will be required, even after the crisis has passed, Texas like the rest of the country stands to gain if she takes advantage of the inevitable increase in travel in the United States that lies ahead." To the editors of the Star Telegram, "the principal project in Texas for attracting more visitors is the establishment of Big Bend National Park, for which $1,000,000 must be raised by popular subscription." The paper cited estimates that "the 90,000-odd tourists who are fleeing from Europe will be expected to travel in the United States next year." In addition, "there is another group known as Winter Tourists, on which Texas should have as much claim as California and Florida." With a vision that seems prophetic in hindsight, the Star Telegram predicted the future economy of leisure and travel that would shape the Lone Star state (and much of the nation as well) for the remainder of the twentieth century, when its editors concluded: "Texas should not fail to seize the opportunity to become a greater tourist State and to profit from the increased travel that is to be diverted from Europe to this country." [36]

The Star Telegram's wishful thinking, while accurate in the long term, did not prevail in the weeks following the onset of World War II. By mid-October, Herbert Maier would report to Director Cammerer that "this Office has had no recent word concerning the status of this matter [fundraising]." It had been five months since Maier had spoken with Amon Carter's representatives. "At that time," said the acting Region III director, "Mr. Carter was abroad; however, early action was promised upon his return which was to occur shortly." Carter's people had advised Maier that "business conditions in Texas did not warrant approaching the heads of the bigger industries for substantial donations." Maier now believed that "business in Texas . . . has increased tremendously during the last few months, due to the War, and the oil and cotton industries are in very sound positions." It was Maier's opinion that "the present, therefore, should be an opportune time for Mr. Carter to launch his appeal." [37]

As the European conflict escalated, and Amon Carter sent no word about the fundraising initiative, park sponsors in Alpine attempted to generate their own publicity with the printing of a bulletin praising the virtues of Big Bend. Horace Morelock confided to Maier that the chamber of commerce felt compelled to publish the bulletin "principally because the park movement did not shape up according to our ideas and hopes." This marked the first admission by Morelock, a tireless advocate for the park, that the effort might be in vain. Morelock thought "that it would be a fine thing if you would write to Mr. Record, indicating that you have had an inquiry from Washington on the subject of the bulletin, also showing the interest of the National Park Service in the Big Bend National Park." Morelock also thought "it imperative that the Parks Committee in Texas buy additional land immediately about the CCC camp in order that this group might do such things as will justify their staying in the Park area." Maier could assist park sponsors by soliciting a "good letter from [Texas CCC director] Mr. Robert Fechner as to the program of the CCC in the park area," as this might "stimulate some of our group to get busy in raising funds." Then he asked if "the National Park Service could not make a contribution, both in money and in service on this score?" This reflected the depths of Morelock's frustration with Amon Carter and the whole fundraising strategy: "I have been a little impatient at the slow progress we have been making in Texas, and I should like to get suggestions from you as to what we might do." Maier needed to know that "personally, I can see no reason for any further delay," and Morelock urged the NPS official: "I feel that some kind of a meeting must be held at an early date if we are to get things under way." [38]

Minus a strategy for raising monies for Big Bend, all parties involved in park planning (the NPS, the state parks board, and local sponsors) had little information to dispense to the news media, and less detail for potential donors or sellers of property. Frank D. Quinn, appointed executive secretary of the parks board in the fall of 1939, told Brewster Kenyon of Long Beach, California, that "the money for the purchase of this land has not yet been raised and we regret we are not now in position to indicate what [Kenyon's 320 acres] might be worth for park purposes." Wendell E. Little, planning coordinator for the NPS office in Washington, attended a meeting in the nation's capital "of ex-students of the University of Texas where the principal speaker was Major Parten of the Board of Regents." Parten's "chief subject of discussion," Little told his superiors, "was the management of the University lands." The NPS planning coordinator believed that "the establishment of the Big Bend National Park would be directly in line with certain stated objectives of the University." The Austin campus "is one of the chief centers of Latin American studies designed to foster goodwill and mutual understanding between the United States and South and Central America." This prompted Little to surmise that "the international aspects of the Big Bend area also tend in this same direction." Logistics also played a role in UT's involvement in the future of Big Bend, said Little, as "the establishment of the park would provide facilities for research by the University and other scientific institutions." He noted that "only recently the University has expanded its research activities and plans are being made for considerable further expansion, provided funds are made available." Thus Little suggested to the NPS that "when the matter of appropriating funds by the Texas Legislature is up for consideration, it may be desirable to discuss the proposed national park fully with officials of the University." He recognized that "a great many of the members of the Texas Legislature are ex-students of the University, and the support of that institution on behalf of the park would carry considerable weight." [39]

Little's correspondence marked the first time that anyone had suggested approaching the Austin campus for assistance in the Big Bend campaign. It also revealed how park sponsors needed to change direction in their quest for Texas's first NPS unit. On November 10, regional director Tolson reported to his Washington superiors that he had met with Governor O'Daniel. The latter "advised that little progress had been made to raise the necessary funds," attributing this to Amon Carter's lengthy stay in Europe, where he had "not given much time to raising funds for the above-mentioned purpose." Moreover, said Tolson, O'Daniel "gave me the impression that he wanted Mr. Carter to have an opportunity to see what he could do to raise funds for purchasing the privately owned areas within the proposed Big Bend National Park area." The governor also stated bluntly that "Mr. Carter would not be very successful in doing so," and that "it would be essential for the Texas legislature to appropriate all, or the major portion, of the funds necessary therefor." Without the promise of private monies, Herbert Maier then had to deny Horace Morelock's request for NPS support of the Big Bend promotional bulletin. The park service itself, said Maier, had printed some 5,000 copies of its own pamphlet on the future park, several of which the NPS had sent to Morelock and other local park sponsors. "It seems best," wrote Maier, "to not release these until a strategic time when [Amon Carter's] campaign actually gets under way." Maier also did not support the idea of Morelock to "contact CCC Director Fechner regarding the purchase of land immediately surrounding the [Chisos] camp." He believed that "easements can no doubt be obtained on such lands on which CCC work is indicated." Maier also hoped that "the State will be in a position to start purchasing some lands shortly from the $40,000 or more that is already at hand." [40]

Local sponsors and NPS personnel committed to the creation of Big Bend National Park had endured perhaps their most bleak period as the days of 1939 dwindled. The year had begun hopefully enough, when Governor W. Lee O'Daniel accepted the entreaties of President Franklin D. Roosevelt and championed the park with Lone Star lawmakers. Positive publicity for the first six months of 1939 (coinciding with the deliberations at the Austin capital) led to O'Daniel's signature on legislation committing the state of Texas to acceptance of lands purchased by private subscription; a process that looked promising because of the active role promised by Amon Carter. Yet the anxieties caused by war surrounded Big Bend, even though the future park site was 10,000 miles from the battlefields of eastern Europe. Thus it came as no surprise to park advocates when in December A.C. Jones of Dallas wrote to Governor O'Daniel, seeking guidance on the future of his property in south Brewster County. In 1928 Jones and Dr. William B. Phillips, director of the Bureau of Economic Geology at UT, had acquired one-eighth of a section (80 acres), with mineral rights, that Jones contended included four miles of the riverbank along the Rio Grande. Jones claimed that Phillips had examined the property and had determined that it contained deposits of "gold that would run over 30 dollars per ton and quick silver that is richer more than five time more than the producing mines near Terlingua City." Jones asked O'Daniel "if you have to take this section of land or mineral rights . . . at 50 cents per acre." If the state wanted Jones's property, "could you the state of Texas pay me in a compensation form for the land that has valuable minerals that is paying quantity." Jones declared that "the reason that [I] hate to lose this piece of land or mineral rights when it could be developed for these minerals" was that "I am [a] disabled soldier or veteran that got hurt in action on the front during the [first] World War." He thus joined hundreds of other property owners in wondering whether the dream of Everett Townsend for a park along the Rio Grande would become one more mystery shrouding the mountains and valleys of the Big Bend. [41]

| |

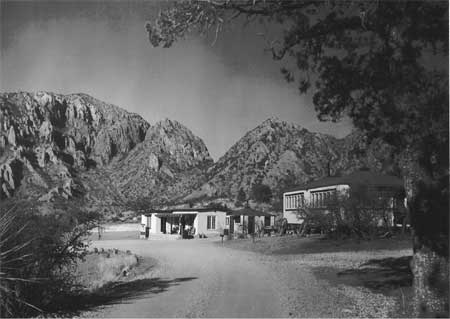

| Figure 12: Chisos Basin Store and Dining Room (c. 1950) | |

Endnotes

1 For a good discussion of the war in Texas and the West, see Gerald D. Nash, The American West Transformed: The Impact of the Second World War (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985).

2 Memorandum of W.F. Ayres to the Acting Regional Director, Region III, NPS, January 7, 1939, RG79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to National Parks, Monuments and Recreational Areas, 1927-1953, Box 11, Folder: 610:01 Purchasing of Lands #1 Big Bend, DEN NARA.

3 Memorandum of Ayres to the Acting Regional Director, Region III, NPS, January 9, 1939, RG79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to National Parks, Monuments and Recreational Areas, 1927-1953, Box 11, Folder: 610.01 Purchasing of Lands #1 Big Bend, DEN NARA.

4 Memorandum of Earl A. Trager, Chief, Naturalist Divison, NPS, Washington, DC, to Acting Regional Director, "Region 3," January 16, 1939; Trager to Dr. Robert T. Hill, Dallas, TX, January 16, 1939, RG79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to National Parks, Monuments and Recreational Areas, 1927-1953, Box 20, Folder: 731.02 Topography of Parks, DEN NARA.

5 Memorandum of Ayres to the Acting Regional Director, Region III, January 19 1939, RG79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to National Parks, Monuments and Recreational Areas, 1927-1953, Box 2, Folder: 120-07 (NPS) Proposed Legislation Big Bend, DEN NARA.

6 John N. Harris, Jr., Dallas, to The State Park Board, Austin, January 24, 1939; Will Mann Richardson, Chief Clerk, TSPB, to Harris, January 26, 1939, Townsend Collection, Folder 4, Archives of the Big Bend, SRSU.

7 Maier to Record, January 24, 1939; Maier to Winfield, January 24, 1939; Memorandum of Maier to the NPS Director, January 24, 1939, RG79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to National Parks, Monuments and Recreational Areas, 1927-1953, Box 2, Folder: 120-07 (NPS) Proposed Legislation Big Bend, DEN NARA.

8 Memorandum of Maier to the NPS Director, January 24, 1939.

9 "Park Area Described As ‘Mysterious, Wild Country With Peculiar Effect On Those Fortunate Enough To See It,'" Alpine Avalanche, January 27, 1939.

10 Memorandum of Ayres to the Acting Regional Director, Region III, NPS, January 31, 1939, RG79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to National Parks, Monuments and Recreational Areas, 1927-1953, Box 2, Folder: 120-07 (NPS) Proposed Legislation Big Bend, DEN NARA.

11 "Elliott Roosevelt Stresses Value of Park in Big Bend," Fort Worth Star Telegram, February 4, 1939.

12 "Bellow Bred Out Of Bulls, Complains J. Frank Dobie," Pampa (TX) News, February 10, 1939.

13 Maier to Townsend, Februrary 21, 1939, RG79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to National Parks, Monuments and Recreational Areas, 1927-1953, Box 11, Folder: 610.01 Purchasing of Lands #1 Big Bend, DEN NARA.

14 Richardson to Hillory A. Tolson, Regional Director, NPS Region Three, Santa Fe, February 23, 1939, RG79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to National Parks, Monuments and Recreational Areas, 1927-1953, Box 11, Folder: 610.01 Purchasing of Lands #1 Big Bend, DEN NARA.

15 Memorandum of Maier for Files, February 27, 1939, RG79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to National Parks, Monuments and Recreational Areas, 1927-1953, Box 11, Folder: 610.01 Purchasing of Lands #1 Big Bend, DEN NARA.

16 Memorandum of Ayres to the Acting Regional Director, Region III, NPS, February 28, 1939, RG79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to National Parks, Monuments and Recreational Areas, 1927-1953, Box 2, Folder: 120 (NPS) Legislation (General), DEN NARA.

17 Daily Report of Ayres to "Austin Headquarters," March 1, 1939, RG79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to National Parks, Monuments and Recreational Areas, 1927-1953, Box 2, Folder: 120-07 (NPS) Proposed Legislation Big Bend, DEN NARA.

19 Daily Report of Ayres, March 4, 1939, RG79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to National Parks, Monuments and Recreational Areas, 1927-1953, Box 2, Folder: 120-07 (NPS) Proposed Legislation Big Bend, DEN NARA.

20 Tolson to Carter, March 7, 1939, RG79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to National Parks, Monuments and Recreational Areas, 1927-1953, Box 2, Folder: 120-07 (NPS) Proposed Legislation Big Bend, DEN NARA.

21 Memorandum of Maier for State Supervisor Fuller, March 17, 1939; Maier to Record, March 17, 1939, RG79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to National Parks, Monuments and Recreational Areas, 1927-1953, Box 2, Folder: 120-07 (NPS) Proposed Legislation Big Bend, DEN NARA.

22 Memorandum of L.C. Fuller, State Supervisor, Recreation Study, NPS, Austin, to the Acting Regional Director, Region III, March 21, 1939, RG79, NPS, SWRO, Santa Fe, Correspondence Relating to National Parks, Monuments and Recreational Areas, 1927-1953, Box 2, Folder: 120-07 (NPS) Proposed Legislation Big Bend, DEN NARA.