|

BIG HOLE

Guidebook 1941 |

|

|

BIG HOLE BATTLEFIELD NATIONAL MONUMENT | ||

|

United States Department of the Interior Harold L. Ickes, Secretary National Park Service, Newton B. Drury, Director |

|

The Big Hole Battlefield National Monument, with its battle-scarred trees and grass grown ring of shallow trenches, marks the site of the outstanding battleground along the line of the famous retreat of Chief Joseph and his fleeing Nez Perce women, children, and warriors. Here occurred on August 9, 1877, one of the more dramatic and tragic episodes during the long struggle in the United States to confine the Indians to ever-diminishing reservations and to force them off land wanted by the whites. The flight of the Indians from Idaho had been marked with a desire to escape peaceably and reach Canada with as little trouble with the whites as possible. While the Indians recovered from the surprise attack of General Gibbon and his command, the loss of warriors, lodges, and supplies was a serious handicap. They were embittered with the realization that every man's hand was against them and for the remainder of their retreat until their capture within a few miles of the Canadian border on October 5, 1877, their action was more ferocious in all their contacts with the whites.

CAUSES OF THE NEZ PERCE WAR OF 1877

Gov. Isaac Stevens, of the Washington Territory, had concluded a treaty with the Nez Perce Indians in 1855 wherein their hereditary lands in the Willowa Valley in Oregon were to be theirs for all time. These lands were soon encroached upon by white settlers and in 1863 the Government concluded another treaty that took these lands from the Indians. All Indian groups did not concede to this treaty. Gen. Howard on May 4, 1877, met with the "Non-Treaty" Indians, or Chief Joseph's division of the tribe, and commanded them to move to their designated reservations. This would have been accomplished without bloodshed had it not been for the growing feeling on the part of the Indians that the whites failed to punish their own people for alleged misdeeds. Some of the young warriors, ignoring the authority of their chiefs, went forth on their own to punish the whites, thus precipitating the movements of troops against these "Non-Treaty" Indians.

General view of Big Hole Battle Site

THE CAMPAIGN OF 1877

Gen. O. O. Howard, June 15, 1877, sent two companies of cavalry to quell uprisings and return the Indians to the reservation. On the 17th a battle occurred at White Bird Canyon, Idaho. The troops were repulsed and the Nez Perce Indians then started their retreat. On July 11 they were overtaken by General Howard with a force of about 500 men at the Clearwater Crossing, Idaho. Here a battle occurred with small losses on both sides and the Indians continued their retreat over the Lo Lo Trail. On July 27, 1877, Capt. Charles C. Rawn met Chief Joseph at the mouth of Lo Lo Creek and demanded that the Indians submit to the authority of the Government. This the Indians refused to do, but they promised to pass through Montana peaceably and to molest no one. This appealed to the Volunteers, who disbanded and returned to their homes. Captain Rawn's force returned to Fort Missoula to await reinforcements. The Nez Perce Indians traveled leisurely, trading with the settlers, secure in the belief that the agreement they had concluded at Lo Lo Creek meant the cessation of hostilities. They arrived at their old camp-ground on the Big Hole River, August 7, 1877.

Gen. John Gibbon had been ordered from Fort Shaw to intercept and hold the Indians. As General Gibbon followed the Indians he added to his command from Fort Missoula and the Bitter Root Valley until his force numbered 17 officers, 146 regulars of the 7th Infantry, and 34 volunteers.

Museum, Big Hole Battlefield

THE BATTLE OF THE BIG HOLE

AUGUST 9, 1877

On the night of August 8, the Indian Camp slumbered while the smoldering fires sent a heavy haze of smoke down the valley on the cold, frosty air. No guard was posted to warn the sleeping Indians of the approaching white troops. More than 2,000 Indian ponies grazed upon the grassy slope above the valley. General Gibbon's command, preparing to attack the Indians, extended in a long line, working its way silently step by step through the willow flat toward the river and the Indian camp. The first grey-tinged streamers of dawn found the entire command within a few yards of the camp, only the shallow river separating them.

Natalekin, an old Indian, arose and started toward the horse herd and, unaware of their presence, approached to within a few yards of the advancing whites. He was shot, and this was the signal for the attack. The entire command charged the camp, pouring a deadly fire into the lodges. They endeavored to set fire to the camp, but many of the lodges would not burn. The confusion and rout of the Indians was complete. Many of the warriors ran out of the village without weapons of any kind.

The deadly fire of the troops and the terrific hand-to-hand fighting in the village drove the warriors to the protection of the willows, leaving the camp in possession of the whites. From fallen members of General Gibbon's command the unarmed Indians secured rifles and commenced firing at the troops in the village. General Gibbon had to retreat across the willow flats to higher ground and the Indians concealed in the willows kept up their effective fire until the whites reached a wooded flat above the river, where they hastily entrenched themselves.

Area where soldiers were beseiged

Leaving a force of their warriors to continue the siege, most of the Indians returned to the village. General Gibbon wrote: "Few of us will soon forget the wail of mingled grief, rage, and horror which came from the camp four or five hundred yards from us when the Indians returned to it and recognized their slaughtered warriors, women, and children. Above this wail of horror, we could hear the passionate appeal of the leaders urging their followers to fight and the war whoops in answer which boded us no good."

The attempt to bring up General Gibbon's howitzer was frustrated by the Indians. They captured the cannon and a pack mule carrying 2,000 rounds of ammunition which was sorely needed by the besieged whites.

Suffering from wounds, hunger, and thirst, the plight of General Gibbon's command was indeed serious. Exposed to the fire of sharpshooters stationed on higher ground to the west, the fight continued without respite throughout the day. One Indian stationed in the large bushy pine trees east of the trenches inflicted serious damage until he was finally located and killed.

The Indian women, children, and old men buried their dead, dismantled the camp, and retreated southward. The warriors continued the siege until 11 p.m., when they fired a farewell volley toward the soldiers and followed the trail of the tribe southward. Thinking that the ensuing quiet was a ruse to get them into the open, the troops kept to the protection of the trenches for the remainder of the night.

Site of Indian village where battle started

Dawn found the Indians gone from the area, leaving behind 83 dead. Of their number, there were 10 women and 21 children killed in the first attack on the village. Some wounded that were carried with them in the retreat died on the trail. General Gibbon reported 29 killed and 40 wounded, himself one of the latter. The Indians continued their march south and east, through what is now Yellowstone National Park, then swung northward and finally surrender ed in the Bearpaw Mountains in northern Montana. Thus ended one of the most spectacular "retreats" in American history and one of the more valiant, though futile, attempts of the Indians to escape from an imposed white-man's civilization.

Bighole Battlefield National Monument

(click on image for a PDF version)

ORIGIN AND PHYSICAL DEVELOPMENTS

The original national monument of 5 acres was created by Presidential Proclamation, June 23, 1910, and was enlarged June 29, 1939, to 200 acres. It does not include the Indians' campsites where the initial attack occurred.

At the national monument there is a small museum, headquarters building, and monuments to the memory of the soldiers, citizens, and Indians participating in the Battle.

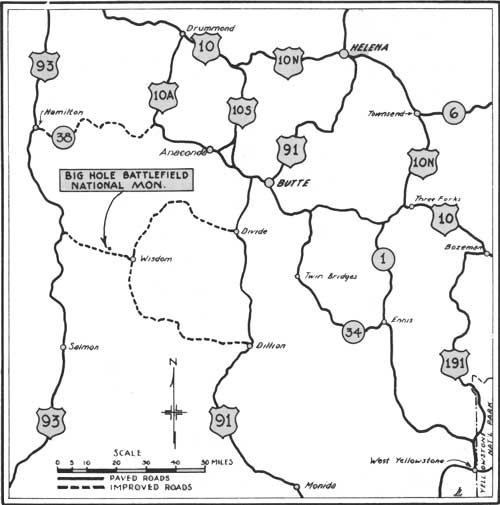

Vicinity Map — Bighole Battlefield National Monument

LOCATION AND ADMINISTRATION

The Big Hole Battlefield National Monument is located in western Montana, 12 miles west of the town of Wisdom. It is part of the National Park Service system and is administered by the Superintendent of Yellowstone National Park who has a representative at the monument from June 15 to September 15 each year. Communications should be addressed to The Superintendent, Yellowstone National Park, Yellowstone Park, Wyo.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> |

1941/biho/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 20-Jun-2010