|

Big Thicket National Preserve Texas |

|

NPS photo | |

Unusual Combinations of the Ordinary

People have called the Big Thicket an American ark and the biological crossroads of North America. The preserve was established to protect the remnant of its complex biological diversity. What is extraordinary is not the rarity or abundance of its life forms, but how many species coexist here. Once vast, this combination of pine and cypress forest, hardwood forest, meadow, and blackwater swamp is but a remnant. With such varied habitats, "Big Thicket" is a misnomer, but it seems appropriate. An exhausted settler wrote in 1835: "This day passed through the thickest woods I ever saw. It . . . surpasses any country for brush."

Major North American biological influences bump up against each other here: southeastern swamps, eastern forests, central plains, and southwest deserts. Bogs sit near arid sandhills. Eastern bluebirds nest near roadrunners. There are 85 tree species, more than 60 shrubs, and nearly 1,000 other flowering plants, including 26 ferns and allies, 20 orchids, and four of North America's five types of insect-eating plants. Nearly 186 kinds of birds live here or migrate through. Fifty reptile species include a small, rarely seen population of alligators. Amphibious frogs and toads abound.

Although Alabama-Coushatta Indians hunted the Big Thicket, they did not generally penetrate its deepest reaches, and the area was settled by whites relatively late. In the 1850s economic exploitation began with the cutting of pine and cypress. Sawmills followed, using railroads to move out large volumes of wood. Ancient forests were felled and replanted with non-native slash pine. Oil strikes around 1900 brought further forest encroachment. Nearby rice farmers flooded some forests; others were cleared for housing developments.

Designation of Big Thicket as a national preserve created a different management concept for the National Park Service. Preserve status prevents further timber harvesting but allows oil and gas exploration, hunting, and trapping to continue. In 2001 the American Bird Conservancy designated Big Thicket National Preserve a Globally Important Bird Area. The preserve is composed of 12 units comprising 97,550 acres It was designated an International Biosphere Reserve by the United Nations in 1981. The protected area will provide a standard for measuring human impact on the environment.

Ecotone, the Edge Effect

Plants and animals characteristic of many regions live together in the Big Thicket largely because of the Ice Age. Continental glaciers far to the north pushed many species southward. Conditions were varied enough that when the glaciers retreated, many species continued living here.

A change in elevation of just a few feet can produce a dramatic change in vegetation. Where habitats meet—called ecotones—life forms are most varied. The Big Thicket has such ecotones in abundance.

Big Thicket Legacies

As rich as its natural history is the area's human history. Caddo Indians from the north and Atakapas to the south knew it as the Big Woods. Much later, Alabama-Coushatta Indians, pushed westward, found shelter here before they finally relocated to a reservation.

Early Spanish settlers avoided this "impenetrable woods," as did early American settlers who named it the Big Thicket before the 1820s, when farms appeared around its perimeter.

Pioneers from Appalachia began to settle here in search of new land, and theirs is the Big Thicket legacy. During the Civil War many Big Thicket citizens went deeper into the woods to avoid conscription. Lumbering geared up when a narrow-gauge railroad was built in 1876. The original forest was doomed.

The Big Thicket—once spread over 3.5 million acres—is now less than 300,000 acres. There are some 97,550 acres authorized for protection within the national preserve.

Some noteworthy Big Thicket residents: Martha Jacobsen lived alone in the woods until she was nearly 100. Self-educated naturalist Lance Rosier was instrumental in preserving the Big Thicket. Bruce Jordan preferred mules or oxen to haul logs from the thicket—they "do better in mud and water ... and don't bog down so bad."

Plants That Eat Insects

Four of the five kinds of carnivorous plants found in the United States grow here: pitcher plant, bladderwort, butterwort and sundew. (The Venus fly trap does not.) Most commonly seen are the pitcher plant and the sundew. The sundew's sticky globules, which look like dew drops, attract and hold insects for the plant to digest.

Visiting the Preserve

Big Thicket National Preserve was established by Congress in 1974. It is managed by the National Park Service.

Visitor Center The visitor center is located at U.S. 69/287 and FM 420, eight miles north of Kountze. Hours are 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. daily.

Accommodations Food and lodging are available nearby in Kountze, Silsbee, Woodville, and Beaumont. There are no accommodations in the preserve.

Weather Expect rain, heat, and humidity. Summer daytime temperatures—from the mid-80s to the mid-90s°F—combined with the rain create a humid climate. Winter daytime temperatures average in the mid-50s°F.

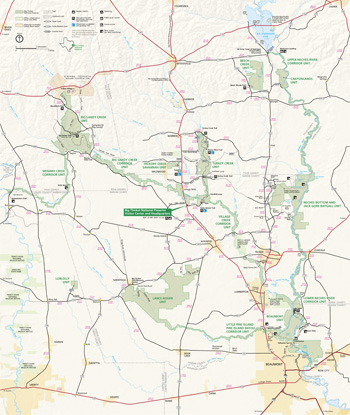

(click for larger map) |

For a Safe Visit

Register at the trailhead and stay on the trail.

• Detour around snakes; some are poisonous. Do not kill snakes;

they are protected as part of the natural scene. • Use insect

repellent and avoid disturbing bee, wasp, or fire ant nests. •

Carry drinking water and do not drink from creeks or ponds.

Protect the Preserve

All plants and animals are protected. Do not collect any specimens.

• Pack out whatever you pack in, and do not litter. • Pets

must be on a six-foot leash. • Vehicles and fires are not permitted

in the backcountry. • Personal watercraft (jet skis) are prohibited

in Big Thicket National Preserve pending legal rulings.

Seasonal Closures The Big Sandy Trail is closed during the Texas hunting season, generally from October 1 to late January each year.

What Is There to See and Do?

Turkey Creek Unit This area has wide plant diversity. A trail leads 15 miles north-south. On the northeast an accessible boardwalk explores the carnivorous pitcher plant area. Kirby Nature Trail leads you across Village Creek's floodplain, introducing you to a variety of plants.

Beech Creek Unit Take the one-mile loop trail to see a remarkably well preserved remnant of beech-magnolia-loblolly pine plant association. Such communities of northeastern and southeastern tree species occur almost exclusively in southeast Texas.

Hickory Creek Savannah Unit Dry, sandy uplands and wetter lowlands result in diverse flowers and grasses. Longleaf pine forest and wetlands mix here. Exposed to natural wildfires, this community will be largely a glade-like park. Without fire, dense shrubs will invade these grasslands. A one-mile trail loops through the unit's eastern part. The accessible boardwalk is 0.5 mile long.

Big Sandy Creek Unit A forest of beech, magnolia, and loblolly pine descends into dense stands of hardwoods in the Big Sandy Creek floodplain. Take the 5.4-mile Woodlands Trail loop through the sloping forest to the creek. The Beaver Slide Trail, a 1.5-mile loop, winds around a series of ponds formed by old beaver dams. Horse and all-terrain bicycle riding are permitted on the 18-mile Big Sandy Creek Trail.

Nature Study With its great diversity of plant and animal life the preserve is the ideal outdoor laboratory. Look, listen, and enjoy. Birding is a favorite activity, especially during spring and fall. From late March to early May hundreds of species pass through on their way north. You can observe fall migrations in October and November.

Naturalist Activities All programs are by reservation only. Call for information and reservations for guided hikes, talks, canoe trips, and educational field experiences.

Trail Hiking There are hiking and nature trails in four preserve units. There are no trails in the river corridors. Permits are not required for hiking, but please register at the trailheads. Stay on the trails; it is easy to become lost. Be prepared for rain and wet trails. If you find a submerged trail while streams are flooded, do not try to follow it; you could step into a deep waterhole. Horses and all-terrain bicycles are permitted only on the Big Sandy Trail. No motorized vehicles are permitted on preserve trails.

Boating and Canoeing Small watercraft may be launched at locations along the Neches River, Pine Island Bayou, and along Village and Turkey creeks. Choose your waters: broad alluvial river, sluggish bayou, or free-flowing creek. Access points have not been developed on creeks, but you can launch at most road crossings. Some boat ramps located on private property charge a launch fee.

Fishing Fishing is allowed in all waters. A Texas fishing license is required and state laws apply. Ask at the visitor center about types of fish and fishing conditions to expect.

Camping Backcountry camping is allowed by permit in certain parts of the preserve. There are no developed campgrounds. Several private and public campgrounds nearby offer tent and recreational vehicle sites. Call the preserve for permit information.

Picnicking There are picnic sites in many of the units. Refer to the map for locations. Some sites have barbecue grills; contained charcoal grills (hibachi-type) are also allowed. Open fires and the collecting of wood are prohibited.

Swimming In the Neches River swim in quiet areas, away from strong currents. The Lakeview Sandbar area in the Beaumont Unit is a popular spot. In summer it is designated a no-wake zone for boaters. Never dive unless you are certain of the depth of the water and that there are no underwater obstacles.

Hunting and Trapping These are allowed only in specific areas at certain dates and times. A permit from the superintendent is required. Please write or call preserve headquarters for details.

Source: NPS Brochure (2004)

Documents

A Socioeconomic Atlas for Big Thicket National Preserve and its Region (Jean E. McKendry, Cynthia A. Brewer, Steven D. Gardner and Joel M. Staub, 2004)

An Annotated Checklist of the Myxomycetes of the Big Thicket National Preserve, Texas (Katherine E. Winsett and Steven L. Stephenson, extract from Journal of the Botanical Research Institute of Texas, Vol. 6 No. 1, 2012)

Archeological Assessment of Big Thicket National Preserve (Harry J. Shafer, Edward P. Baxter, Thomas B. Stearns and James Phil Dering, October 1975)

Discovery of a Neches River Ferryboat: Big Thicket National Preserve (James E. Bradford, 1992)

Final General Management Plan/Environmental Impact Statement, Big Thicket National Preserve (August 2014)

Final Oil and Gas Management Plan Environmental Impact Statement, Big Thicket National Preserve (December 2005)

Fire Management Plan, Big Thicket National Preserve (2004)

Foundation Document, Big Thicket National Preserve, Texas (May 2014)

Foundation Document Overview, Big Thicket National Preserve, Texas (June 2014)

Geologic Resource Evaluation Report, Big Thicket National Preserve NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRR-2018/1779 (Trista L. Thornberry-Ehrlich, October 2018)

LANDSAT Remote Sensing Study of the National Park Service Big Thicket National Preserve NASA Information Bulletin No. 1 (undated)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Big Thicket National Preserve NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/BITH/NRR-2016/1355 (Andy J. Nadeau, Kathy Allen, Anna Davis, Kevin Benck, Lonnie Meinke, Sarah Gardner, Shannon Amberg and Andy Robertson, December 2016)

Natural Resources Foundation Report, Big Thicket National Preserve NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/WRD/NRR-2010/180 (Robert Sobczak, James C. Woods, Greg Eckert, Ellen Porter and David L. Vana-Miller, February 2010)

Protecting the National Parks in Texas Through Enforcement of Water Quality Standards: an Exploratory Analysis NPS Technical Report NPS/NRWRD/NRTR-94/18 (Ronald A. Kaiser, Steven E. Alexander and J. Porter Hammitt, November 1994)

Soil Survey for Big Thicket National Preserve, Texas (1978)

Vegetation of the Active Stream Flood Plain of the Neches River in the Upper, Mid-Corridor, Jack Gore Baygall and Neches Bottom Units (Jim C. Woods, 1985)

Epitaph: Saving the Big Thicket National Preserve - Texas Parks and Wildlife (Official)

bith/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025