|

Rails East to Promontory The Utah Stations |

|

HISTORICAL SKETCH

A concept to link the nation by rail became a reality on May 10, 1869 and America's frontier was nearly history (Fig. 2). Construction of the first transcontinental railroad and the meeting of the Union and Central Pacific Railroads at Promontory Summit not only contributed to the development of the west but, in fact, pulled the west coast ito the continental mainstream. The "Iron Horse" opened the American West, traversed imposing mountain ranges, and made it possible to ship and travel the width of the country in days instead of weeks or months. A stage coach from Omaha to Sacramento required continuous travel for more than 20 days. Now with the railroad, the same passage was possible in less than a week.

|

| Figure 2: One of the last emigrant wagon trains heading west meets one of the first locomotives heading east at Monument Point, Utah, May 8, 1869. |

The building of a transcontinental railroad to link the potentially rich and opportunistic western lands to a prospering east where manufactured commodities were readily available was not totally an eastern concept. In 1852, two years after becoming a State, the California legislature resolved:

" . . . . the interest of this State, as well as those of the whole Union, require the immediate action of the Government of the United States for the construction of a national thoroughfare connecting the navigable waters of the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans for the purpose of national safety, in the event of war, and to promote the highest commercial interests of the Republic, and granting the right-of-way through the states of the United States for the purpose of constructing the road." (State of California in Kraus 1969a:7)

A potential route was selected and surveyed in 1853 and 1854 by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The Corps, led first by Captain J. Gunnison and replaced by Lieutenant E.G. Beckwith, surveyed through Utah in May 1854. The survey party suggested a route paralleling the Hastings road, south of the Great Salt Lake, through the Salt Lake Desert and over a low pass at the south end of the Pilot Range (Fig. 3). Unfortunately, Beckwith's survey concentrated primarily on flora, fauna, and native Americans rather than the practical aspects of building a railroad (Beckwith 1854:18-30).

|

| Figure 3: The Gunnison/Beckwith proposed railroad route through Utah in 1854. (click on image for a PDF version) |

In 1857, Californian, Theodore Dehone Judah, presented the shortcomings of the survey to Congress. Unsuccessful in acquiring support for another survey, Judah returned home. His perseverance paid off and within two years he had inspired the California legislature to organize the Pacific Railroad Convention. Judah, the chief spokesman and engineer, called for detailed surveys of potential railroad routes. Finally by 1861, the initiative of the Convention resulted in: (1) stock shares being sold in a private enterprise, the Central Pacific Railroad Company of California, and (2) a formal proposal being sent to Congress to enlist financial aid for the rail line. Judah approached Congress once again. With the country engaged in a civil war, Judah gained Congressional support stating that his railroad would "Unite the Nation". The Pacific Railroad Act was created, endorsed by the 37th Congress, and signed into law by President Lincoln on July 1, 1862 (Kraus 1969a:13-45). No single action changed the complexion of the vast trans-Mississippi west in a shorter period of time than the passage of this Act.

The Act called for the creation of the Union Pacific Railroad Company for construction of a railroad and telegraph westward from a point on the Missouri River near Omaha, Nebraska. (Note: construction actually began at the west bank of the River in December 1863. A bridge was installed to Council Bluffs, Iowa in 1872 [Barry Combs, Union Pacific Railroad Company, personal communication]). Likewise, the Central Pacific Railroad Company was to construct a railroad and telegraph eastward from the Pacific Coast at or near San Francisco or the navigable waters of the Sacramento River (Kraus 1969a:45, 37th Congress 1862:489).1 Other provisions allowed for a 200-foot right-of-way on either side of the track including ground as needed for construction of machine shops, stations, camps, and other essential facilities. It also granted the privilege to remove earth, stone, and timber materials necessary in construction. Three amendments, in following years, provided additional grants and aid (Kraus 1969a: 45).

1. The Union and Central Pacific Railroads received the first authority to build under the New Act. The Northern Pacific was chartered in 1864; The Atlantic and Pacific in 1868, and the Texas Pacific in 1871 (Department of the Interior, BLM 1962).

Dependent upon all manufactured material coming from the east, the Central Pacific waited. Work trains, tons of iron spikes, rails, and tools were required and had to be shipped by boat, around South America to San Francisco, then by steamer up the Sacramento River. Depending upon the terrain and construction difficulties, the Central Pacific, and Union Pacific, received loans of $16,000 to $48,000 for every mile of track laid. Additionally, to obtain revenue, both were allocated every alternate section of public land adjacent to the rail line (mineral lands exempt) (Kraus 1969a:45). This acreage, formed a basis of credit with which to secure financing.2

2. Central Pacific, 7,481,280 acres, Union Pacific 18,979,659 acres (Department of the Interior, BLM 1962).

Ceremonies, appropriate to the occasion, launched construction in Sacramento, January 8, 1863. It required five years of arduous manual labor, assisted only by hand tools and blasting powder to carve the route and lay rails through the Sierra Nevada. It was during this period that the principal ownership of the Central Pacific was consolidated by "The Big Four": Leland Stanford, company president and Governor of California, Collis P. Huntington, financial wizard and Central Pacific lobbyist in Washington, Mark Hopkins, Sacramento merchant and company treasurer, and Charles Crocker, chief contractor of construction.

The first train reached Reno on June 11, 1868. With the deep snow and precipitous mountains behind, the construction pace picked up and construction crews moved swiftly across the Nevada Desert (Fig. 4).

|

| Figure 4: A work train in the Nevada (Southern Pacific, Alfred A. Hart Photograph) |

However, in the Great Basin there were other problems. Coal deposits were unknown so timber was utilized for fuel. Often only sagebrush powered the locomotives (Griswold 1962:298). Timber for ties was also a problem. Redwood trees, hewn in California, were transported and laid into central Utah. After leaving the Humbolt River in central Nevada, surface water for the locomotives and construction crews was virtually nonexistent. Drilled wells were often found dry and when water was found, miles of redwood aqueduct transported the water to holding tanks along the track. Water trains were then filled and driven to the railhead (Fig. 5, Kraus 1969a:203).

|

| Figure 5: A water train on a siding during construction of the railroad. Note the Chinese laborers to the side of the track (Southern Pacific, Alfred A. Hart Photograph). |

At track's end, horse-drawn wagons were stationed to provide water, food, and materials to more than 10,000 workers moving east across the desert (Figs. 6, 7). A vast majority of the workers were Chinese (Figs. 8, 9), and their contribution to the railroad construction is immeasurable. Indians, indigenous to the area, also worked alongside the Chinese (George Kraus, Southern Pacific Railroad Company, personal communication).

|

| Figure 6: Telegraph Installation Accompanied Track-laying in the Great Basin Desert (Southern Pacific, Alfred A. Hart Photograph) |

|

| Figure 7: Railroad construction camp (Southern Pacific, Alfred A. Hart Photograph). |

|

| Figure 8: Chinese work gangs, horse-drawn carts, and hand tools accomplished much of the grading work (Southern Pacific, Alfred A. Hart Photograph). |

|

| Figure 9: A lithograph of Chinese railroad workers from Harper's Magazine 1869 (Golden Spike National Historic Site) |

Known as "Crocker's Pets," the Chinese each received wages of $30 to $35 a month and were divided into groups of 30 men. Each group selected a leader who received all wages and bought group provisions. The Chinese workers are credited for saving $20 a month. Every night before supper, the Chinese workmen enjoyed hot baths in used powder kegs. Warm tea was available at the work site (Kraus 1969b:41).

"Systematic workers these Chinese - competent and wonderfully effective because (they are) tireless and unremitting in their industry . . . their workday is from sunrise to sunset, six days a week. They spend Sunday washing and mending, gambling, and smoking." (Alta Californian in Kraus 1969a:217).

"They quickly picked up the necessary smattering of pidgin English. Otherwise they remained a segment of old Canton set down in Nevada, and remarkably unaffected by their change.

Their blue cotton smocks and trousers and their broad basket hats were ideal for the climate. When the felt-soled slippers of the new arrivals wore out, they purchased American boots at the company commissary, the price checked off against their wages due. The fit seems seldom to have been very good, for it remained a continuing joke among the superior whites that a Coolie always insisted on his full money's worth in the form of the biggest boots he could get. (McCague, 1964:104-105).

Survey crews from both companies advanced (Figs. 10, 11) far ahead of railroad construction. By the spring of 1868, Central Pacific surveyors staked a line east across Nevada and Utah into Wyoming. Union Pacific surveyed a line as far west as the California border (Kraus 1969a:126).

|

| Figure 10: Track laying in the Great Salt Lake Desert (Golden Spike National Historic Site) |

|

| Figure 11: Track laying in the Utah desert (Southern Pacific, Alfred A. Hart Photograph). |

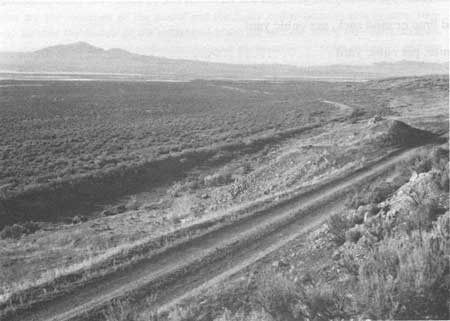

Grade construction followed the survey crews in advance of the track laying. Rivalry flared as both the Union Pacific and Central Pacific graders often worked side by side. This resulted in parallel grade construction between Monument Point and Ogden, Utah and possibly into southwestern Wyoming. Officials of both railroad companies were optimistic that their line would receive the final right-of-way and the contracts and benefits included (Kraus 1969a: 228-229). Today parallel railroad grades are obvious and can be seen between Corrine, Utah and Monument Point at the north end of the Great Salt Lake (Fig. 12).

"From what I can observe and hear from others, there is considerable opposition between the two railroad companies, both lines run near each other, so near that in one place the U.P. is taking a four foot cut out of the C.P. fill to finish their grade, leaving the C.P. to fill the cut thus made, in the formation of their grade.

"The two companies' blasters work very near each other, and when Sharp and Young's men first began work, the C.P. 'let her rip.' The explosion was terrific. The report was heard on the Dry Tortugas, and the foreman of the C.P. came down to confer with Mr. Livingston about the necessity of each party notifying the other when ready for a blast. The matter was speedily arranged to the satisfaction of both parties." (Deseret Evening News, March 31, 1869, in Kraus 1969a.238).

|

| Figure 12: Parallel railroad grades near Metataurus, Utah. Central Pacific, foreground, Union Pacific, middle ground (BLM Photograph) |

With limited grade construction remaining for both railroads, Leland Stanford awarded a construction contract to Mormon Church leader Brigham Young amounting to more than $2,000,000. Brigham subcontracted the work to prominent church members and ward bishops. Among them were Joseph Young, President Lorenzo Snow, Ezra T. Benson of Logan, Mayor Lorin Farr, and Chauncey W. West of Ogden. Although disappointed that the railroad would follow a northerly course and bypass the capitol, the Mormons were eager to see its completion (Reeder 1970:21).

The contract called for construction of 200 miles of grade west from Ogden (Reeder 1970:45). The various jobs entailed in a grading contract, for the Union Pacific in Echo Canyon, may be analogous to contracts along the Promontory Branch:

| Earth excavation, either borrowed for embankment, wasted from cuts, or hauled not exceeding 200 feet from cuts into embankment, per cubic yard | $ 0.27 |

| Earth excavation, hauled more than 200 feet from cuts into embankment, per cubic yard | $ 0.45 |

| Loose rock, per cubic yard | $ 1.57-1/2 |

| Solid lime or sand rock, per cubic yard | $ 2.70 |

| Granite, per cubic yard | $ 3.60 |

| Rubble masonry in box culverts, laid in lime or cement per cubic yard | $ 5.85 |

| Rubble masonry, laid dry, per cubic yard | $ 5. |

| Masonry in bridge abutments and piers, laid in lime mortar or cement, beds and joints dressed, drafts on corners, laid in courses, per cubic yard | $13.50 |

| Rubble masonry in bridge abutments and piers, laid dry, per cubic yard | $ 7.20 |

| Rubble masonry in bridge abutments and piers, laid in cement per cubic yard | $ 7.65 |

| Excavation and preparation of foundation for masonry at estimate of engineer. | |

| (Deseret Evening News, May 20, June 9, 1868 in Reeder 1970:31-32). | |

Virtually all the earth moving was accomplished with hand tools and horse-drawn carts. Nitroglycerin was limited and blasting powder was used for large rock cuts.

Records of Mormon construction camps are limited. Field investigations near Promontory Summit found architectural features diagnostic of grade and track laying camps (Anderson 1978 & 1980). The authors and Anderson identified tent platforms and dugouts, some with masonry walls and fireplaces. West of the Promontory Mountains, the authors failed to locate isolated grade construction and track laying camps other than those which later became railroad maintenance stations. This may be explained by the relatively flat terrain of the Great Salt Desert. Consequently grade construction moved rapidly (Appendix I) and housing became less permanent.

News accounts that describe Mormon grading in Echo Canyon for the Union Pacific, provide an impression of what camps may have been like in the Salt Desert:

Echo City, July 13, 1868

"BELOVED NEWS: - - We are here: and the railroad is coming. Already it is estimated, one half, if not more of the track down Echo Canyon is ready for the ties and rails.

"A birds-eye view of the railroad camps in Echo Canyon would disclose to the beholder a little world of concerted industry unparalleled, I feel safe to assert, in the history of railroad building. All classes of profession, art and avocation, almost, are represented. Here are the ministers of the gospel and the dusky collier laboring side by side. Here may be seen the Bishop on the embankment and his 'diocese' filling their carts, scrapers and shovels from the neighboring cut. Here are the measurer of tapes and calico and the homeopathic doctor in mud to their knees or necks turning the course of the serpentine torrents.

"Here the driver of the quill finds grace in propelling a pick. The man of literature deciphers hieroglyphics in prying into the seams of sand rock. 'Our Local,' when last seen, was itemizing on a granite point with sledge and drill to beat 300 yards or less into 'kingdom come,' or a big fill hard by; and 'Our Hired Man' had pitched into a dugway of loose rock high upon the mountain side, several fathoms above 'eternity's gulf stream' to carve out a new channel for the tide of travel, the track for the iron horse having absorbed the Pioneer road. Here the grey haired scissors-grinder and the editor returning to his wits, with a third party, supposed to be, had formed a co-partnership to run a cart without a horse on a hillside cut. One there was of the homogenus who 'plead' leave of absence to defend a contraband distillery. But such an illustrious corps of practical railroad makers must surely leave their mark. The above are real life pictures . . . (Deseret News, July 22, 1868 in Reeder 1970:33-34).

Clarence Reeder summarized the Mormon railroad construction efforts:

"A people working together in harmony under the guidance of their religious leaders to accomplish a temporal task which they treated as though it were divinely inspired." (Reeder 1970:35).

A Mormon railroad grader, James Crane from Sugarhouse, Utah penned this song which typifies the industrious gaiety of the Mormon workers:

"At the head of great Echo there's a railroad begun,

And the "Mormons "are cutting and grading like fun;

They say they'll stick to it, till it is complete

And friends and relations they long again to meet.CHORUS

Hurrah! Hurrah! for the railroad's begun!

Three cheers for our contractor, his name's Brigham Young!

Hurrah! Hurrah! we 'er honest and true,

For if we stick to it's bound to go through.Now there's Mr. Reed, he's a gentleman true,

He knows very well what the "Mormon" can do;

He knows in their work they are lively and gay,

And just the right boy's to build a railway.CHORUS - - - Hurrah! Hurrah! etc.

Our camp is united, we all labor hard;

And if we work faithfully we'll get our reward;

Our leader is wise and industrious too

And all the things he tells us we 'er willing to do.CHORUS - - - Hurrah! Hurrah! etc.

Hurrah! Hurrah! etc.

The boys in our camp are light-hearted and gay;

We work on the railroad ten hours a day;

We'er thinking of the good time we'll have in the fall,

When we'll take our ladies and off to the ball.CHORUS - - - Hurrah! Hurrah! etc.

We surely must live in a very fast age;

We've traveled by ox teams, and then took the stage;

But when such conveyance is all done away

We'll travel in steam cars upon the railway.CHORUS - - - Hurrah! Hurrah! etc.

The great locomotive next season will come

To gather the Saints from their far distance home;

And bring them to Utah in peace here to stay,

While the judgements of God sweep the wicked away.CHORUS - - - Hurrah! Hurrah! etc.

(Deseret News, August 12, 1868, in Reeder 1970:35-26)

During the final months of 1868, track-laying crews from the east and west began to converge on Utah. Officials from the Union and Central Pacific lobbied in Washington for approval of their rail line through Utah. Rivalry continued on both sides and as late as March of 1869, the approved route through Utah remained unclear. Finally on April 9, 1869, an agreement was reached. The Central Pacific and Union Pacific construction crews were to join rails at Promontory Summit. Ogden, Utah would serve as the common terminus and junction of the two roads. In agreement, the Union Pacific would continue construction but the Central Pacific would pay for and own the rail line from Ogden to Promontory Summit (Kraus 1969a:241-242).

Although the route and ownership of the railroads were resolved, the spirit of competition between the Union Pacific and Central Pacific continued. Both companies raced to reach Promontory first.

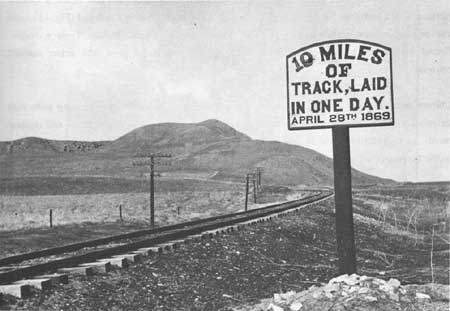

Earlier that year, Charles Crocker claimed that Central Pacific could lay ten miles of track in one day. Rival construction camps of the Union Pacific laughed at the boast. Legend states that Vice President Durant of the Union Pacific wagered $10,000 that it could not be done. Crocker covered the bet and on April 28, 1869, the Chinese and a handful of Irishmen accomplished a feat that still challenges engineers today (Kraus 1969a:248).

"The scene was an animated one (wrote the man from the Bulletin). From the first 'pioneer' to the last tamper, about two miles, there was a line of men advancing a mile an hour; iron cars with their load of rails and humans dashed up and down the newly-laid track; foremen on horseback were galloping back and forth. Keeping pace with the track layers was the telegraph construction party. Alongside the moving force, teams were hauling food and water wagons. Chinamen with pails dangling from poles balanced over their shoulders were moving among the men with water and tea."

(San Francisco Bulletin in Griswold 1962:309)

Wesly Griswold elaborates with a vivid account of the construction and day's events:

'At seven o 'clock, the Central Pacific's well-drilled construction forces began their greatest day's march. At this moment, the first of five supply trains was already panting at the railhead. When the whistle of its locomotive screamed for the contest to begin; a swarm of Chinese leaped onto the cars and began hurling down kegs of bolts and spikes, bundles of fish plates, and iron rails. 'In eight minutes, the six teen cars were cleared, with a noise like the bombardment of an army;' wrote the San Francisco Bulletin's correspondent.

"The train was then pulled back to a siding to make way for the next. As it chugged away, six-man gangs lifted small openwork flatcars onto the track and began loading each of them with sixteen rails plus kegs of the necessary hardware to bolt the rails together and fasten them to the ties. These little flatcars, called 'iron cars,' had rows of rollers along their outer edges, to make it easier to slide the rails forward and off when they were needed. Two horses, in single file, with riders on their backs, were then hitched to each car by a long rope.

"While this was being done, three men with shovels, who formed the army's advance guard and were called pioneers, moved out along the grade, aligning the ties. They did this by butting them to a rope stretched out parallel to a row of stakes that the railroad's surveyors had driven to mark the center line of the track.

"At rails end stood eight burly Irishmen, armed with heavy track tongs. Their names were Michael Shay, Patrick Joyce, Michael Kennedy, Thomas Dailey, George Elliott, Michael Sullivan, Edward Killeen, and Fred McNamara. They waited now beside a portable track gauge, a wooden framed measuring device for making sure that the rails they laid were always 4 feet, 8-1/2 inches apart. Two additional men handled the gauge, moving it just ahead of the tracklayers all day long.

"As soon as the first iron car had been hauled forward, with a Chinese gang aboard, its horses were released and led aside. The Chinese quickly stripped the car of its kegs of spikes, bolts and fish plates, and broke them open. They poured the spikes over the stack of rails, so that they would dribble onto the ground as the rails were removed. The bolts and fish plates were loaded into hand buckets to be carried where they were needed.

The Irish tracklaying team split in half, two men taking up positions at each end of the rail car on both sides. As each forward pair grabbed one end of a rail and quickstepped ahead of it, the rear pair guided the other end along the car's rollers and eased it to the ground with their tongs. Each rail, 30 feet long and weighing an average of 560 pounds, was in place within 30 seconds.

"Behind the rail handlers followed a gang that started the spikes - eight to a rail and attached fish plates to the rail joints by thrusting bolts through them. After them, came a crew that finished the spiking and tightened the bolts. In their rear moved the track levelers, who hoisted tie ends and shoveled dirt under them in order to keep the rails on an even level. They were guided by the gestures of a surveyor 'reverend looking old gentleman,' noted the Bulletin's reporter who kept sighting along the finished track. At the back of the line tramped the biggest contingent of all - 400 tampers, with shovels and tamping bars to give the track a firm seating.

"As each iron car was unloaded, it was lifted and turned around. The horses were rehitched to it and hauled it back to the supply dump at a run. It was lifted off the track whenever it got in the way of a full car headed for the front, and in time to prevent the latter from having to slow down.

"When the whistle blew for the midday meal, Crocker's 'pets,' as the Chinese were often called, and their Irish advance guard had built six miles of railroad. Strobridge insisted on fresh horses for the iron cars every 2-1/2 miles. He also had a second team of track-layers in reserve, but the proud gang that had laid six miles of rails before lunch insisted on keeping at it throughout the rest of the day.

"The better part of an hour was lost after lunch at the tedious job of bending rails, for the remainder of the 10-mile stretch was a steady climb and full of curves. This was done in a crude way; by placing each rail between blocks and hammering a bend into it.

"When the curved rails were ready, the construction army resumed its march. By seven o 'clock in the evening, the Central Pacific Railroad was 10 miles and 56 feet longer than it had been 12 hours earlier.

"Each man in Strobridge's (Central Pacific Construction Superintendent) astonishing team of tracklayers had lifted 125 tons of iron in the course of the day. The consumption of materials was even more impressive: 25,800 ties, 3,250 rails, 28,160 spikes, and 14,080 bolts.

As soon as the epic day's work was done, Jim Campbell, who later became a division superintendent for the Central Pacific, ran a locomotive over the new track at 40 m.p.h., to prove that the record breaking feat was a sound job as well. Then the last emptied supply train, pushed by two engines, was backed briskly down the long grade to the construction camp beside the lake, with 1,200 men riding on its flatcars."

(Griswold 1962:309-312).

A sign along the grade commemorates the race and laying of 10 miles of track in one day (Fig. 13).

|

| Figure 13: Ten Miles of Track Laid in One Day (Southern Pacific Photograph). |

On April 28, 1869, only four and eight miles respectively separated the Central and Union Pacific from their mutual goal. Considerable grade work remained, however, before the Union Pacific could lay tracks on in to Promontory. A newspaper of April 30, 1869 states:

The last blow was struck on the Central Pacific Railroad and the last tie and rail were placed in position today."

(Alta Californian in Kraus 1969a:256).

The Union Pacific met the Central Pacific on Promontory Summit, May 10, 1869 and the transcontinental railroad was completed (Fig. 1, 14). A Nation previously divided by a "region of savages and wild beasts, deserts of shifting sands, and whirlwinds of dust" (Webster in Kraus 1969a: 13) was now united. America obtained a network of communication and transportation that brought the Nation together. The industrial revolution was accelerated. New markets were opened in the West for finished eastern products. Vast deposits of minerals, timber resources, and agricultural lands became accessible; the country was truely united.

|

| Figure 14: The meeting of the Union Pacific and Central Pacific at Promontory Summit, May 10, 1869 (Charles Russell Photo). |

Accompanying the construction of the transcontinental railroad was the establishment of siding and section facilities. Each section station served a ten to twelve mile section of railway. The station housed work crews and equipment necessary to maintain and repair a specific portion of the railroad. An inventory of the Salt Lake Division of the railroad (Fig. 15) notes the original section stations built in 1869. These stations, Lucin, Bovine, Terrace, Matlin, Gravel Pit (Ombey), Kelton, Ten-Mile (Seco), Lake, and Rozel grew into active railroad centers.

|

| Figure 15: An 1869 inventory of buildings on the Salt Lake Division of the Transcontinental Railroad (Courtesy of Southern Pacific). (click on image for a PDF version) |

Chinese section gangs carried out maintenance work, and improvements to keep pace with deterioration and erosion. Culverts, bridges, and ties required constant attention and replacement. As locomotives grew in size and weight, section crews installed heavier rails. As rail traffic increased, water pipelines and holding tanks were installed, rebuilt or replaced.

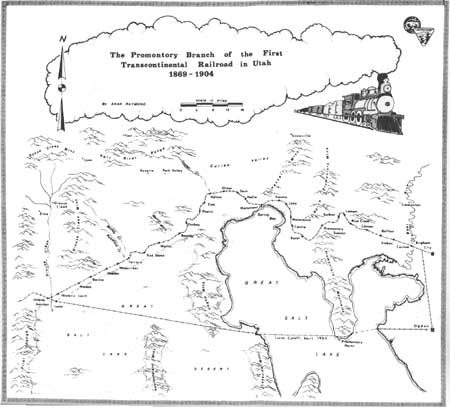

On March 17, 1884 the Central Pacific officially became the Southern Pacific Railroad3 Company (Southern Pacific Railroad Company, 1955:31). Soon 11 rail sidings were installed to keep pace with expanded settlement, commerce, and ranching. Sidings allowed trains to pass others that had stopped to load, unload, or take on water. By 1902 as many as ten trains per day (five each direction) travelled through northern Utah (Daily Train Schedule, Box Elder News, 1902). With completion of the Lucin Cutoff in 1904, most transcontinental traffic began crossing the Great Salt Lake by trestle and merged with the Promontory Branch at Lucin. The new line, built by the Southern Pacific, was 40 miles shorter and eliminated the difficult grades of the Promontory Branch (Fig. 16). Shortly after completion of the cutoff, the workmen, their families, and the support public, whose livelihood depended upon the railroad and the Promontory Branch, began leaving. Only a few trains a week passed through (Bebee 1963:120). In 1942, the rails were removed for steel in World War II and the ties scavenged for the fence posts (Golden Spike Oral History, Larsen 1979). Today, the few people who travel the route are hunters, recreationists, and railroad buffs.

3. The Southern Pacific Railroad Company was incorporated on Dec. 2, 1865 to build a rail line between San Francisco and San Diego, then east but was purchased by the Central Pacific prior to any construction. In 1870 the "Big Four" reorganized the Southern Pacific and used its name unofficially until 1884 (Heath and Campbell, 1926-30:54-55).

|

| Figure 16. The Promontory Branch of the Transcontinental Railroad, 1869-1904. (click on image for a PDF version) |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

ut/8/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 18-Jan-2008