|

Booker T. Washington National Monument Virginia |

|

NPS photo | |

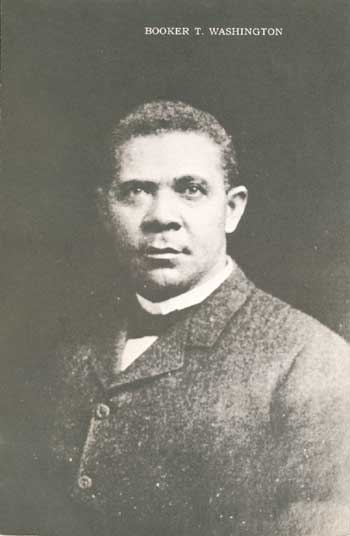

There was a time in America when human beings were bought and sold. A written inventory cataloged the slaves on the Burroughs farm in Virginia in 1861, their monetary worth calculated according to the work they could do. On this list was a little boy, named simply "Booker," valued at $400. Farmer James Burroughs never anticipated that one day his young slave would be remembered for his value in promoting education for all black Americans.

Up From Slavery

Booker T. Washington recalled his childhood in his autobiography, Up From Slavery. He was born in 1856 on the Burroughs tobacco farm, which, despite its small size, he always referred to as a "plantation." His mother was a cook, his father a white man from a nearby farm. "The early years of my life, which were spent in the little cabin," he wrote, "were not very different from those of thousands of other slaves."

He went to school in Franklin County—not as a student, but to carry books for one of James Burroughs's daughters. It was illegal to educate slaves. "I had the feeling that to get into a schoolhouse and study would be about the same as getting into paradise," he wrote. In April 1865 the Emancipation Proclamation was read to joyful slaves in front of the Burroughs home. Booker's family soon left to join his stepfather in Malden, W. Va. The young boy took a job in a salt mine that began at 4 a.m. so he could attend school later in the day. Within a few years, Booker was taken in as a houseboy by a wealthy townswoman who further encouraged his longing to learn. At age 15 he walked much of the 500 miles back to Virginia to enroll in a new school for black students. He knew that even poor students could get an education at Hampton Institute, paying their way by working. The head teacher was suspicious of his country ways and ragged clothes. She admitted him only after he had cleaned a room to her satisfaction.

In one respect he had come full circle, back to earning his living by menial tasks. Yet his entrance to Hampton led him away from a life of forced labor for good. He became an instructor there. Later, as principal and guiding force behind Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, which he founded in 1881, he became recognized as the nation's foremost black educator.

Washington the public figure often invoked his own past to illustrate his belief in the dignity of work. "There was no period of my life that was devoted to play," Washington once wrote. "From the time that I can remember anything, almost every day of my life has been occupied in some kind of labor." This concept of self-reliance born of hard work was the cornerstone of Washington's social philosophy.

As one of the most influential black men of his time, Washington was not without his critics. Many charged that his conservative approach undermined the quest for racial equality. "In all things purely social we can be as separate as the fingers," he proposed to a biracial audience in his 1895 Atlanta Compromise Address, "yet one as the hand in all things essential to mutual progress." In part, his methods arose from his need for support from powerful whites, some of them former slave owners. It is now known, however, that Washington secretly funded antisegregationist activities. He never wavered in defending his belief in freedom: "From some things that I have said one may get the idea that some of the slaves did not want freedom. This is not true. I have never seen one who did not want to be free, or one who would return to slavery."

By the last years of his life, Washington had moved away from many of his accommodationist policies. Speaking out with a new frankness, Washington attacked racism. In 1915 he joined ranks with former critics to protest the stereotypical portrayal of blacks in a new movie, Birth of a Nation. Some months later he died at age 59. A man who overcame near-impossible odds himself, Booker T. Washington is best remembered for helping black Americans rise up from the economic slavery that held them down long after they were legally free citizens.

1856 Born April 5 on the Burroughs farm.

1865 Moves with family to join stepfather in Malden, W. Va.

1872-75 Attends Hampton Institute. Becomes a teacher and returns to Hampton as instructor in 1879.

1881 Founds secondary school for blacks in Tuskegee, Ala. As first principal, builds school into respected institution.

1895 Delivers Atlanta Compromise Address on September 18; calls for interracial cooperation in economic matters without eliminating social segregation. Speech propels him to national prominence.

1895-1915 As leading black educator, continues to promote industrial education. Publishes autobiography Up From Slavery in 1901. Despite disagreements in philosophy with civil rights colleagues, is a powerful politica! force and acknowledged speaker for black Americans.

1915 Dies and is buried at Tuskegee. Survived by wife Margaret and children.

Tuskegee Institute

Putting into practice his philosophy that hard work builds character—land facing a severe funding shortage—Washington and his students constructed Tuskegee Institute themselves, brick by brick. They even manufactured their own bricks. The science building was completed in 1893.

With the founding of the school, the Wizard of Tuskegee launched an industrial and teaching curriculum that he proudly billed as "not for the select few, but for the masses."

Young Booker: Child-slave in Tobacco Country

"My master and his sons all worked together side by side with his slaves," Booker T. Washington explained about his boyhood home, in contrast to life on larger plantations. "In this way we all grew up together. ... There was no overseer, and we got to know our master and he to know us."

Like others in the region, the Burroughs farm was small, 207 acres, and as self-contained as possible. In the minds of these farmers, self-sufficiency meant owning slaves, since paid labor would have further diminished farm profits already marginal. James Burroughs had only about 10 slaves. There was always work to be done and young Booker was expected to do simple chores from the time he could walk. "I was not large enough to be of much service," he said in his autobiography, "still I was occupied most of the time in cleaning the yards. carrying water to the men in the fields, or going to the mill."

Reaping Cash and Crops from Rocky Soil

In the Deep South, cotton was king. In the Virginia Piedmont, tobacco ruled the economy from colonial times well into the 20th century. Here on small farms, slaves cultivated the dark-leaf variety of Nicotiana tabacum that was, according to an 1870 government report, of "the best descriptions, always commanding the highest prices." About half of the acreage was unimproved. The other half, divided up by zigzag, split-rail fencing, was planted with crops or provided grazing for livestock. Crops other than tobacco were grown for use on the farm. Women wove flax into rough cloth for garments. Corn, wheat, and oats were stored in open cribs and used as feed for livestock or ground into meal. The corn crib was elevated to discourage rodents.

For all its importance, tobacco took up only a small percentage of a farmer's land—probably no more than five acres on the Burroughs farm.

Its cultivation required intensive labor, though, far more than needed for any other crop. Early in February tobacco seeds were sown into a well-fertilized plant bed near a source of water. The field was prepared and divided into even rows of small hills into which the young shoots were later transplanted. Slaves tended the plants throughout the growing season. They cleared weeds; picked off insects; removed the bottom leaves, which sapped food and energy; and trimmed buds at the top to strengthen the leaves and prevent the plants from going to seed. In early September, when the leaves were mature, slaves harvested the plants and readied them for curing.

Hewn Logs for Plain Living

Booker T. Washington was born in a one-room log cabin on the Burroughs property. His mother was a cook and the little dwelling doubled as a kitchen. "The cabin was without glass windows," Washington wrote. "It had only openings in the side which let in the light and also the cold, chilly air of winter." Booker and his brother and sister slept on the dirt floor bundled in rags. Farm cats wandered in and out through a hole in a corner of the cabin. Booker remembered his mother "cooking a chicken late at night, and awakening her children for the purpose of feeding them." He presumed his mother wanted them to eat under the cover of darkness before the owners found out the chicken was stolen. James and Elizabeth Burroughs, along with several of their 14 children, lived in the "big house." Despite its name it had only five rooms. Like the kitchen cabin, the house was constructed of hewn logs chinked with clay. Booker recalled that when he had "grown to sufficient size, I was required to go to the 'big house' at mealtimes to fan the flies from the table by means of a large set of paper fans operated by a pulley." Listening to the family's dinnertable conversation on such occasions, young Booker picked up news of the outside world.

Curing and Storing Golden Leaves

Tobacco plants were harvested whole. In preparation for curing, they were split lengthwise from the top and hung upside down on five-foot-long oak sticks called laths. The laths, holding six to eight plants each, were suspended across poles in the tobacco barn. Every step of the process was undertaken with great care so as not to bruise or tear the valuable leaves.

The leaves were cured for several days over small wood fires built on the dirt floor of the barn. This phase was often overseen by itinerant curers who traveled from farm to farm in autumn. The following spring, when seasonal moisture had made the leaves less brittle, they were taken to a local tobacco factory. Planters hired out their slaves to these factories to stem, cut, and shape the tobacco into plugs and twists for chewing, the popu|ar form of tobacco consumption at the time.

Animals for Food and Farm Work

In the heart of tobacco country, little attention was paid to the science of raising livestock. Planters kept animals that provided food for themselves and their slaves or that otherwise earned their keep.

ln 1850 the Burroughses owned four horses, which they sheltered in a horse barn. Besides serving as the family's transportation, they pulled plows through fields and wagonloads of cured tobacco leaves to factory. Washington recalled taking sacks of corn on horseback to a local mill.

A few head of cattle, including "four milch cows," appeared under Burroughs's name in the 1860 county census. In warm weather milk and butter were cooled in a box through which the spring flowed. Sheep provided meat and wool. For food and bedding feathers, the Burroughses kept chickens, ducks, geese, and guinea fowl.

Salted pork, the main source of meat for slaves, came from hogs that roamed free most of the year. If the hogs wandered off their owner's lands, they often became the property of whoever found them. In late fall the hogs were fattened on corn—one of Booker's chores—and butchered. The salted meat was hung in the smokehouse to cure over a smokey fire.

An Acre of Fresh Fare

Female slaves tended the gardens. Enclosed by a picket fence, the vegetable garden took up about an acre, space sufficient "to supply a large family with an abundance of vegetables," according to a contemporary report.

Workers hoed, planted and weeded, kept plants free of insects, and ensured a steady supply of fresh peas, greens, and cucumbers in summer. Cabbages were wintered over in the ground and sweet potatoes were stored in a pit in the kitchen cabin. Beets and cucumbers were pickled and herbs and beans were dried.

Forging the Necessities of Farm Life

As essential as iron implements were to an agricultural enterprise, few farms in the area had full-time blacksmiths. Smiths at a nearby shop in Hales Ford shod horses, hammered out new tools, and constructed wagons and machinery. Itinerant blacksmiths were hired to make major repairs. Slaves undertook minor projects and small carpentry jobs in the blacksmith shed.

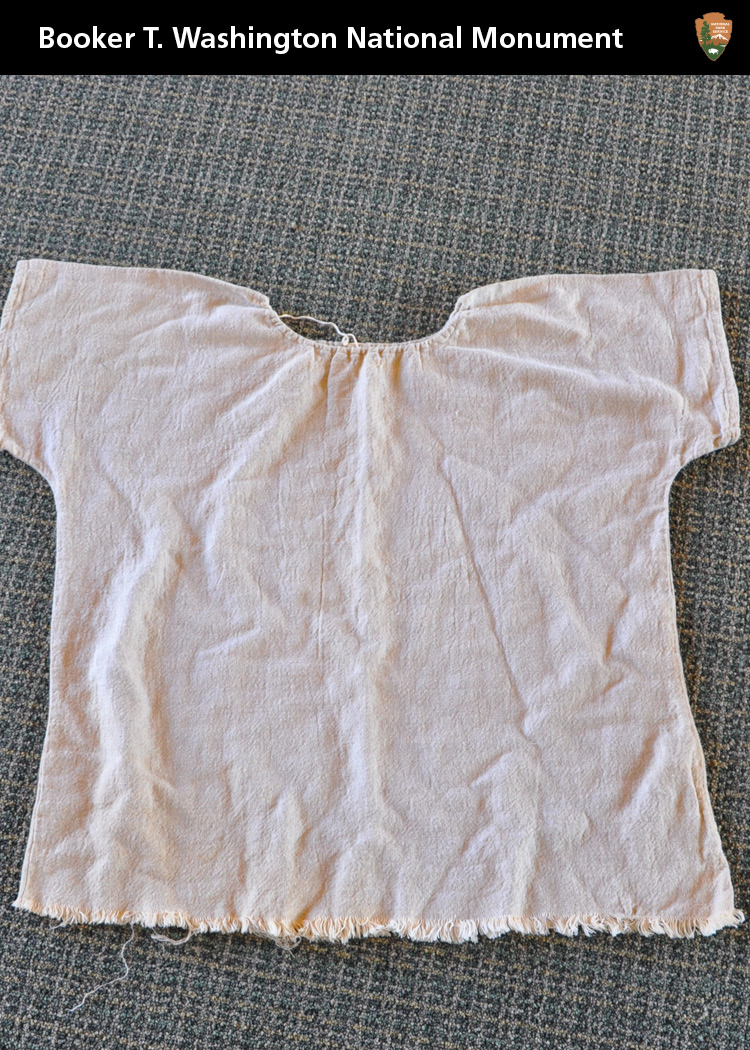

Farm workers also manufactured soap, candles, baskets, and shakes for shingles, which continually needed replacing. To produce clothing, flax was woven into rough, prickly linen cloth that Booker recalled vividly: "I can scarcely imagine any torture, except, perhaps, the pulling of a tooth, that is equal to that caused by putting on a new flax shirt for the first time."

Note The site is restored to its general appearance in the mid-19th century. All buildings standing today are reconstructions. The site of a slave cabin similar to the one in which Washington was born and the site of the Burroughs house have been outlined with stones and are shown as ghost images.

A white oak tree by the spring and a catalpa tree and juniper tree north of the Burroughs house site were growing here during the 1850s.

About Your Visit

(click for larger map) |

Booker T. Washington left the Burroughs farm in 1855 at age nine, poor, uneducated, and newly freed. When he returned for a visit in 1908, he was a college president and influential statesman. In 1957, 101 years after Washington was born, this national monument was established to commemorate his life and work. The park comprises 239 acres, including most of the Burroughs's original 2O7 acres, as well as reconstructed farm buildings. Demonstrations of farm life in Civil War Virginia help bring to life the setting of Washington's childhood.

Facilities There are no dining or camping facilities at the park. There is a picnic area near the parking lot. Nearby towns have restaurants and motels.

The visitor center building, restrooms, and emergency telephone are accessible to persons in wheelchairs. Along the Plantation Trail the terrain is hilly, and the path is unpaved in some places. Rangers will provide assistance if needed. For information about group tours and special events contact the park staff in advance.

Things to Do Begin your tour with the audiovisual program and exhibits at the visitor center. Park rangers are on duty to answer questions and provide information. A self-guiding tour along the Plantation Trail leads you through the historic section of the park. Guided tours and special events are scheduled in summer.

A Natural Setting Native plants and trees grow along the Jack-O-Lantern Branch Heritage Trail. The trail winds through many acres of the original Burroughs property. This wooded area is probably much like it was when Washington was growing up. There are several cemeteries on the park grounds. Near the picnic area is the cemetery where plantation owner James Burroughs and his son Billy, who was killed in the Civil War are buried.

Location The monument is located on Va. 122 (Booker T. Washington Highway), 22 miles southeast of Roanoke, Va. From I-81 take I-581, then U.S. 220 south from Roanoke to Va. 122. From the Blue Ridge Parkway take Va. 43 south to Va. 122. From Lynchburg take U.S. 450 west to Va. 122.

Related Sites Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site in Alabama is located on the campus of the industrial school that Washington founded in 1881 and which is still operating today. George Washington Carver noted botanist and Booker T. Washington's colleague at Tuskegee, is honored at his namesake national monument in Missouri.

Other National Park Service sites devoted to the lives and accomplishments of black Americans are Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site in Richmond, Va; Frederick Douglass National Historic Site in Washington, D.C.; Martin Luther King, Jr., National Historic Site in Atlanta, Ga; Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site near Tuskegee Institute, Ala.; and Boston African American National Historic Site in Boston, Mass.

Source: NPS Brochure (2010)

|

Establishment Booker T. Washington National Monument — April 2, 1956 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Brochures ◆ Site Bulletins ◆ Trading Cards

Documents

A Small Park With a Big Story: An Administrative History of the Booker T. Washington National Monument (Claudrena N. Harold, June 2021)

Abbreviated Final General Management Plan/Environmental Impact Statement, Booker T. Washington National Monument (January 2000)

Agriculture on the Burrough Plantation 1856-1865 (Barry Mackintosh, December 13, 1968)

Booker T. Washington National Monument: An Administrative History (Barry Mackintosh, June 18, 1969)

Booker T. Washington: An Appreciation of the Man and His Times (HTML edition) (Barry Mackintosh, 1972)

Booker T. Washington National Monument: An Assessment and Alternative Interpretation (Willie L. Barber, extract from High Plains Applied Anthropologist, Vol. 21 No. 2, Fall 2001)

Comprehensive Interpretive Plan, Booker T. Washington National Monument (March 1999)

Cultural Landscape Report for Booker T. Washington National Monument: Site History, Existing Conditions, Analysis, and Treatment (Lisa Nowak, H. Eliot Foulds and Phillip D. Troutman, February 15, 2013)

Draft General Management Plan/Environmental Impact Statement, Booker T. Washington National Monument (June 1999)

Ethnographic Overview and Assessment: Executive Summary, Booker T. Washington National Monument (Willie Baber, September 15, 1998)

Foundation Document, Booker T. Washington National Monument, Virginia (February 2018)

Foundation Document Overview, Booker T. Washington National Monument, Virginia (June 2018)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Booker T. Washington National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2010/234 (T.L. Thornberry-Ehrlich, August 2010)

Historic Resources Study: Booker T. Washington Elementary School and Segregated Education in Virginia, Booker T. Washington National Monument (Scot A. French, Craig Barton and Peter Flora, June 2007)

Historic Structures Report, Administrative and Historical Data, Part I: Reconstruction of Slave Cabin, Booker T. Washington National Monument (J.J. Kirkwood and Chester L. Brooks, June 1959)

Historical Research Management Plan, Booker T. Washington National Monument (Barry Mackintosh, June 1968)

Long-Range Interpretive Plan, Booker T. Washington National Monument (Date Unknown)

Interpretive Prospectus for Booker T. Washington National Monument (H. Gilbert Lusk, May 31, 1968)

Junior Ranger Program, Booker T. Washington National Monument (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Junior Ranger Program: The Pathway to Sucess, Booker T. Washington National Monument (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Booker T. Washington National Monument (Burroughs Plantation) (Diann L. Jacox, October 1989)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Booker T. Washington National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/BOWA/NRR-2017/1558 (Todd Lookingbill, Heather Courtenay, John Finn, Regan Gifford, Nadia Hatchel, Meghan Mulroy, Andrew Pericak and Matt Rouch, December 2017)

Park Newspaper (The Grapevine Telegraph): Summer 2011 • Fall 2011

Reconnaissance Report, Booker T. Washington Birthplace, Virginia (W.T. Ammerman, October 1953)

Studies in the Local History of Slavery (Roy Talbert, Jr., Gary Lee Cardwell and Andrew L. Basin, 1978)

The Hales Ford Community 1856-1865 (Barry Mackintosh, November 13, 1968)

Up From Slavery: An Autobiography (Booker T. Washington, 1902)

Inside the Outside — Booker T. Washington National Monument (New Moon Creative Media, LLC, 2014, Duration: 29:26)

Measure of a Man (National Park Service, Duration: 12:51)

What's A Heaven For? (National Park Service, 1966, Duration: 17:19)

Books

bowa/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Aug-2024