|

Bryce Canyon

Historic Resource Study |

|

REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT

CONCEPT-ORIGINS

By the early 1920s four major parties recognized Bryce Canyon's scenic potential. These included: (1) the influential citizens of Salt Lake City, acting through Utah's State government; (2) the National Forest Service; (3) the National Park Service; and (4) the Union Pacific System. Each party was interested in the Canyon's development for different reasons, and each was thus apt to rate its importance differently. All parties, however, were unanimous on two issues. First, if Bryce Canyon's development was pursued, the cooperation of the remaining three groups was essential. Second, any meaningful physical plan for Bryce Canyon was inseparable from the more general economic development of southwestern Utah.

On paper the State of Utah stood to gain the most from nationally popularizing Bryce Canyon. In the summer of 1922, however, Salt Lake City's most important boosters had temporarily directed their attention elsewhere. They were captivated by the Wasatch summit drive project, and were convinced that this attraction near the capital would hold up westbound motorists for several days. A good chunk of the tourist auto traffic might not even bother going on to the coast. For the time being, substantial investments in southwestern Utah by the State would have to wait.

One high ranking Forest Service official, Acting Forester F. A. Sherman, considered that the Salt Lake people were on the "wrong tack." [46] In Sherman's opinion, Utah's version of an Alpine scenic highway was unlikely to hold up more than 25 percent of the westbound motorists. Even those who took the drive could tear through it in a day and continue westward. Sherman's contention was that tourists from east of Colorado were psychologically primed for California. These people were only inclined to stop in Salt Lake City to see the Mormon Tabernacle, maintenance their automobiles, gas up, and move on.

Sherman firmly stated where he thought the State should place its primary emphasis:

It is my feeling that Utah's best bet, which is also Salt Lake's best bet, is to emphasize and capitalize the very unique attractions in the southern part of the State, such as Bryce's Canyon, Cedar Breaks, Zion National Park, and the Grand Canyon. Their aim should be to divert the west-bound traffic south from Salt Lake through their State to Bryce Canyon, Grand Canyon, Zion Canyon, Cedar Brakes [sic], and then westward. Of course they (tourists) will not be spending their money in Salt Lake City, but you will see enough of Utah to realize that most of the money left in the State eventually finds its way into the capital city. [47]

The Forest Service realistically knew that leadership in the development of southwestern Utah was not going to come out of Salt Lake City. Nevertheless, whoever took charge would have to lend a sympathetic ear to public opinion emanating from the capital.

A report monitoring recreation problems in District 4 was presented to Forest Service officials in Washington, D. C., during the fall of 1922 by "collaborator" Frank A. Waugh. He noted the geographic unity of southwestern Utah, the acute need for better roads, and the assessment that Bryce Canyon presented the most urgent problems in the entire District. Waugh thought it incumbent on the Forest Service to take lead in making Bryce Canyon a national monument. By effecting an exchange of Forest Service lands, the agency was in a position to acquire Section 36 from the State with a minimum of delay. Waugh recommended the prompt appointment of a Forest Ranger for the area, a topographical survey, and careful reconnaissance for available water. [48] His well thought out report also presented the first known physical plan for Bryce Canyon.

I . . . recommend that, in order to avoid serious mistakes, a development plan for this area be worked out at the earliest possible opportunity. This plan should cover, amongst other features, the following:

1. Location of hotel and attached camps, with ground plan for the same.

2. Location and equipment of public camp-ground for automobile tourists.

3. Location, distribution and allocation of water supply.

4. General sanitary plans.

5. Suitable approach to camp and to rim view.

6. Trails along the rim of the Canyon.

7. Trails into the Canyon.

8. Location of store, post office and other services.

9. Location of public garage and service station.

10. Aeroplane landing. (Someone has already been at the Canyon looking for such a landing.)

11. All night camps in the Canyon. [49]

Steven Mather, the first Director of the National Park Service, was undoubtedly interested in the scenic region of southwestern Utah. He was, however, against including Bryce Canyon in the National Park System. [50] Mather preferred to have Bryce Canyon become Utah's first State park, and urged this course of action upon Governor Charles R. Mabey and the State Legislature. On December 19, 1921, a general meeting of all interested parties was convened in Salt Lake City to create a State Park Commission. In accordance with Mather's wishes, the "Committee on Legislation and Geographic Boundaries" recommended that Bryce Canyon be made the first of a series of State parks. [51] Only in 1924, when the State failed to do anything with Bryce, did Mather agree to Bryce Canyon's acquisition as a national monument. Given this status it would be provisionally administered by the Forest Service.

Because of its considerable financial resources and the company's willingness to invest in projects that promised to turn a tidy profit, the Union Pacific was probably the party most actively interested in Bryce Canyon. There were, however, formidable problems involved in the development of Bryce Canyon, and these the company had to carefully weight against future gains. The Union Pacific had two immediate problems. The first was to assess its relationship to the State of Utah, the Forest Service, and the National Park Service and determine how cooperative these agencies would be to one another. The second involved ascertaining the intentions of the Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad (D.& R.G.), whose existing track to Marysvale, Utah, positioned it to outflank a major developmental project by the Union Pacific.

Section 36 rightfully appeared to Union Pacific officials as the key to Bryce Canyon's future development. If the State refused to implement a conciliatory policy, the railroad's investment in Bryce Canyon was an unjustifiable risk. Major difficulties were not anticipated with the Forest Service. In fact, the Union Pacific would have preferred to deal exclusively with the Forest Service, in lieu of the National Park Service. [52] Mather's opinion of Bryce Canyon was probably known to Union Pacific officials, which implied that friction over Bryce Canyon between Federal agencies would be minimal.

Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad

J. W. Humphrey once made an effort to interest the Denver and Rio Grande (D. & R.G.) Western Railroad in Bryce Canyon, shortly after its "discovery" in the spring of 1916. He explained how tourist traffic could be easily linked to the North Rim of the Grand Canyon, and "other attractions down that way." [53] At about the same time the Union Pacific reputedly received the pictures and color movies shot in Bryce Canyon by Forest Service photographer George Goshen. [54] Why one railroad had its interest aroused and the other did not is an issue worth examining.

The growth of southern Utah's livestock industry and the promise offered by metallic ore deposits in the area prompted the D. & R.G. to extend its trackage from Thistle, Utah, to Marysvale. The first train entered Marysvale on August 7, 1890, [55] and construction of Marysvale's depot followed 9 years later. [56] In 1915 a big mining boon struck Marysvale. Gold was discovered in the mountains near town, although workable claims proved short lived. A more important resource proved to be nonmetallic alunite ore, from which alumina oxide and potash as a by-product were extracted. As long as the German embargo of potash lasted during World War I, an Armour subsidiary—Mineral Products Corporation—prospered. Three additional companies outside Marysvale concentrated exclusively on mining crushed potash ore for the manufacture of ammunition and fertilizer. [57]

Within a few short years Marysvale grew from a town of a few hundred to several thousand.

Horse drawn carriages and hacks met the train each morning to pick up the passengers and cart them off to either the Bullion Hotel, the Pines, the Grand Hotel, the Marysvale Hotel or the Straw Place. [58]

At this juncture the D. & R.G. supposedly executed plans to push its trackage all the way to Flagstaff. [59] Marysvale's economy again took a radical turn when the war's end dramatically braked the demand for high-cost aluminum. Potash could be imported more cheaply than mined in Utah. The town's economy began to slip into a steady decline. By the early 1920s both freight and passenger traffic were way off standards set during the teens.

During the clement months of 1922, however, some tourist traffic was still routed through Marysvale. Touring automobiles from three outfits eagerly met the morning Salt Lake City mail train. Arthur E. Hanks operated out of Marysvale. He conducted a 1-1/2 day tour to Bryce Canyon, as well as a 4-1/2 day junket to the North Rim via Bryce Canyon. H. I. Bowman headquartered his touring service out of the Highway Garage in Kanab, Utah. Given his location, it was necessary for him to base tours on the number of miles traveled:

50 cents per mile 5 passenger car (4 passengers and driver);

60 cents per mile 7 passenger car (6 passengers and driver); a minimum of 20 miles will be charged for each day. Two children under six years of age carried in lieu of one adult; 25 pounds baggage per capita carried free. [60]

Only Parry Brothers of Cedar City offered tours to Bryce Canyon, the North Rim, Zion National Park, and Cedar Breaks. Touring was expensive in the early 1920s. The Parry Brothers' North Rim-Bryce Canyon excursion, a 5-day affair, cost each adult $80; the 8-day Bryce, North Rim, Zion, Cedar Breaks loop $140. [61]

Notwithstanding the light volume of tourist traffic conducted through Marysvale, the Union Pacific (UP) was deeply concerned about the D. & R.G.'s future plans for Marysvale. On October 17, 1921, W. S. Basinger, Passenger Traffic Manager of the company, directed a brief report to H. M. Adams, Vice President in charge of traffic for U. P.; in it Basinger frankly expressed his uncertainty over the matter:

The construction of a railroad only a part of the way into the scenic territory would simplify very materially the problem of developing it in that respect, in that it would decrease the distance for auto transportation. The general impression exists that most of this territory is valueless except for its scenic attractions. The fact is quite the contrary and I feel sure that the opportunities for successful development, both from a freight and passenger standpoint, are large and are well worth careful consideration.

The D. & R.G. now have a line extending south from Thistle, Utah, to Marysvale, which is situated at the north end of the territory described. From time to time there are rumors that this line will be extended. Some of these rumors state that the extension will be on account of the large amount of lumber available. Others are based on oil development of which there are some indications. Whether, however, the D. & R.G. have ever given serious consideration to the extension of this line, I am unable to say. [62]

As early as 1916 J. W. Humphrey had gotten the distinct impression from D. & R.G. officials in Salt Lake City that any plans to build a tourist hotel at Marysvale, or to provide company bus service to scenic attractions, was out of its line. Humphrey inferred from his interview with unspecified personnel that "possibly financial difficulties of their H. H. System prevented them from undertaking a new project of that kind." [63] An examination of D. & R.G. archival materials does suggest that the company was in and out of financial trouble during the early 1920s. [64]

An intracorporate letter, dated August 22, 1922, proves that by this time the Union Pacific felt it could accurately ascertain the D. & R.G.'s position regarding the southern Utah tourist trade. This key piece of correspondence was directed from Union Pacific President Carl H. Gray to Judge H. S. Lovett, Chairman of the company's Executive Committee in New York City.

I have discussed the question of D. & R.G.W. competition with Mr. J. H. Young [unidentified]. He tells me they will be glad to enter into the same arrangement with us that they now have for Yellowstone Park excursions, establishing a line of rates which would permit passengers to go from Denver to Salt Lake City via the D. & R.G.W., to be delivered to our line at that point, in which event, they would not put in any excursion rates permitting a side trip to Marysvale. This would bring all excursion business which moves via either line, to one railroad from Salt Lake City to Cedar City. I would regard this as a satisfactory arrangement from both standpoints, because I cannot believe they can ever satisfactorily handle passengers over this long branch with the character of service which they could afford to provide. I think we can safely disregard Marysvale as an element of competition. [65]

UNION PACIFIC SYSTEM

The letter from Gray to Lovett, quoted above, is notable in other respects. In it the U. P.'s President explained along general lines how the company intended to develop the scenic attractions of southwestern Utah. Gray also illuminated the underlying justification for what would amount to a massive expenditure of approximately $5,000,000. [66] The more specific problem of Section 36 in what was soon to become Bryce Canyon National Monument was temporarily ignored.

Gray was convinced that Cedar City, Utah, should be made the hub of the U. P.'s proposed development. This could only be realized if a spur were constructed into Cedar City from the main line, which ran through Lund, Utah, 33 miles to the northwest. Cedar City would require a large, modern hotel. It would also be necessary to construct smaller hotels in Zion and Bryce and a luncheon pavilion in Cedar Breaks. For the time being Gray thought the Union Pacific should not involve itself in the development of the North Rim, given the extremely poor state of the road, via Kanab, which led into this attraction. Roads were also of uneven quality in southwestern Utah, but Gray felt that with the cooperation of State and Federal agencies the most pressing problems could be overcome. The railroad did not want to assume any direct responsibility for the construction or improvement of roads, but did want the exclusive right to transport tourists over them.

President Gray and his closest advisers were thinking big. They wanted to soon advertise a major tourist attraction, whose season lasted at least a month longer than Yellowstone's. They also saw no theoretical reason why a trinity of first-rate attractions, properly developed, managed and advertised, would not rival the annual volume of tourism to Yellowstone. [67] Gray appears to have based his position—in part at least—on earlier information which passed between Basinger and Adams.

This information was in Basinger's September 1921 report to Adams, which described the former's North Rim trip. It included a meaty section on the "Possibility of Tourist Travel" for North Rim and environs. At the time Basinger was convinced the Union Pacific System needed convention sites for Pacific Coast groups that could provide accommodations "early in June and as late as October, to which we are unable to offer Yellowstone Park and the members of which are induced for that reason to use the Santa Fe [to South Rim] or the Canadian Pacific." [68] Basinger also stressed his belief that with proper roads and hotel accommodations at North Rim the Union Pacific could put a dent in the Santa Fe Railroad's South Rim traffic. [69] As noted above, Gray's letter to Lovett, dated August 14, 1922, suggests he gave less credence to this part of Basinger's report.

Lund-Cedar City Spur

On October 24, 1921, President Gray instructed Vice President of Traffic H. N. Adams to direct "quiet investigations," on the part of the Traffic Department, for the purpose of ascertaining the feasibility of a rail line from Lund to Cedar City. Thereafter, the project moved forward quickly. On February 5, 1922, Gray wrote to H. V. Platt, Manager of the Oregon Short Line. He explained to Platt how Omaha planned to justify the Lund-Cedar City Spur to the company's Executive Committee in New York City. Basically, Gray thought the real potential lay in the excursion business; but, admittedly, this would only be a paying proposition for 3 or 4 months a year. [70] To convince the Executive Committee—and by extension, Union Pacific investors—it would be necessary to offer additional inducements for the spur's construction. These were readily available.

Gigantic deposits of iron ore were believed to exist just northwest of Cedar City. [71] Southwestern Utah had also gained a reputation for the fertility of its arable land. Agronomists had proven that anything, with the exception of citrus fruit, could be grown in this part of the State. [72] Therefore, the promise of a lucrative freight traffic in ore and fresh foodstuffs certainly abetted Gray's argument. The Columbia Steel Corporation, which operated three large plants—one at Ironton, Utah, and the other two in Pittsburg and Torrance, California—had, in fact, recently secured claims to iron ore in the Iron Springs District, 10 miles west of Cedar City. [73] Columbia had no efficient means of transporting its ore from iron Springs to Lund, and so proposed to construct a rail line. In August 1922, Columbia founded a subsidiary for the purpose, whose legal name was the Iron County Railroad Company. [74]

It is coincidental that two independent corporations should have developed a simultaneous interest in a spur from Lund to Cedar City or its environs. It is highly doubtful, however, that the Union Pacific found the situation at all amusing. Action was called for and the Union Pacific took the initiative as was its custom. Columbia wanted access to the main line at Lund, and the Union Pacific wanted to see this access realized, providing the track used was its own. Apparently, Columbia was approached late in the summer of 1922 by Union Pacific representatives and agreed to withdraw its application to the interstate Commerce Commission (I.C.C.) if the Union Pacific would build the Lund-Cedar City Spur, do it quickly, and provide the Iron Springs District ready access to it. During the last week of August 1922 the I.C.C. approved the Union Pacific's petition. [75] This cleared away the first major obstacle for the proposed development of the high plateau country.

The citizens of Cedar City were understandably eager to see the railroad come into their town. Consequently, they readily agreed to conditions imposed by the Union Pacific, which included the following. First, Cedar City was required to furnish the right-of-way from Lund, and guarantee fulfillment by posting a $50,000 bond, Second, the city was to sell two downtown blocks to the Union Pacific at a cost not to exceed $45,000. The Citizen's Committee of Cedar City agreed to absorb any amount in excess of this figure. [76] Local cooperation was all the railroad had a right to expect. On June 27, 1923, the first scheduled train into Cedar City from Lund arrived, bearing President Warren C. Harding and his entourage. A few weeks later, on September 12 the completion of the Lund-Cedar City Spur was officially celebrated by the laying of a "golden rail." [77]

Cedar City Complex

The third and final condition imposed on Cedar City by the Union Pacific involved what was to become the core building in the railroad's Cedar City Complex. [78] In 1918 the townspeople had begun the construction of a large hotel. From its onset the project was badly under-financed, and by the summer of 1922 the hotel was only half completed. [79] Omaha wanted to purchase the building for estimated costs expended on it, less interest. This sum amounted to $77,597.14, and the railroad assumed it would take another $100,000 to open the hotel. [80] Actually, this estimate was only about 50 percent of what the Union Pacific poured into the structure, but it was ready for business late in 1923. [81] The hotel was named "El Escalante" in honor of Friar Escalante who had traversed the region in 1776 (see Modern Discovery, Expeditions to the Bryce Canyon Region).

Construction of the Cedar City depot was accomplished during the first 6 months of 1923. George Albert "Bert" Wood, a Cedar City contractor, did the work. He was also responsible for completing the Escalante Hotel and later participated in building the Utah Parks Lodges. The depot was rounded out in 1929 when a patio and bus shelter were added to its south and east sides. [82] Between 1925-29 the completion of four buildings augmented the complex. These were the West Garage (1925), Chauffer's Lodge (1926), Machine Shop (1928), and Commissary Building (1929). [83]

Incorporation of Utah Parks Company

Omaha's decision to go ahead with the Cedar City Complex carried with it the realization that sooner or later the railroad would need to conclude long-term concession agreements with the National Park Service. Director Mather of the National Park Service made it clear to Union Pacific as early as March 1922 that he thought the railroad should operate in the Cedar City region as two separate companies. One should take the responsibility for transportation and related services, the other for hotels and camps. Mather suggested that transportation be handled as an extension of the railroad—and hotels and camps by "Utah people," with the financial backing of the railroads.

Mather knew well the political climate in Washington, D. C., and was particularly concerned about Enos Mills' agitation against what Mather called "so-called monopolies" in the national parks. [84] Members of the Appropriation Committee for the Interior Department who had visited the parks were generally pleased with cooperation between western railroads and the Park Service; but, Mather sensed that constant agitation could raise questions in the minds of constituents, and put unwanted pressure on friendly politicians. [85] Mather's message to the Union Pacific was clear: why needlessly antagonize these politicians? Omaha was essentially forced to concur with Mather's position.

There were also secondary reasons why the formation of a separate corporation for concessions made sense to the railroad. For one thing it would limit legal responsibility, and as Gray once remarked to Lovett "a great railroad is much more subject to attack in such matters than a smaller and independent corporation." Additionally, Gray felt a separate corporation, dealing on a day to day basis with a well-heeled, discriminating, carriage trade, would "avoid compromising [the] railroad in the thousand and one little elements of dissatisfaction arising in [the] operation of hotels." [86]

Articles of incorporation for the "Utah Parks Company" (UPC) were drawn up in Salt Lake City on March 26, 1923, antedating by several months the opening of the Escalante Hotel in Cedar City. Article V established the UPC's responsibility, not only for a wide range of tourist accommodations, but for transportation facilities as well:

The business of this corporation . . . shall be as follows to own, lease, operate and maintain automobiles, automobile busses, trucks and other self propelled vehicles and to establish, maintain, operate and conduct a general automobile, livery, and garage business and service including the hiring out of automobiles of any and all kinds, and the care, repair, maintenance supply thereof, together with the necessary buildings, shops, service stations, and other facilities necessary or incident thereto . . . [87]

The Railroad Securities Company of New Jersey, a Union Pacific subsidiary, subscribed 98 percent of the Utah Parks Company's capital stock. High officials of the railroad assumed key positions in the new company. Gray became the Utah Parks Company's President and H. M. Adams the Vice President. Both E. S. Calvin, Union Pacific's Vice President of Operations, and George H. Smith, General Counsel for the Union Pacific System, became Utah Parks Company Directors. [88]

Section 36, Bryce Canyon

In August 1922 Union Pacific's President, Carl B. Gray, was willing to temporarily ignore the problems posed by Section 36 in soon-to-be Bryce Canyon National Monument, but not for very long. Intensive negotiations with the State of Utah were opened in April 1923. Gray telegramed Governor Mabey on April 19 proposing that the railroad buy the 30 acres along the Plateau rim and sign a 25-year lease for the remainder of the section. Gray made it perfectly clear to Mabey that the Union Pacific was willing to agree to certain limitations on the lease. Gray emphasized that Section 36 would never be closed to the public. Areas for parking and camping would be set aside by the railroad for the State's use, at no charge to either the general public or State. [89]

Ten days later Gray telegramed George Smith, informing him precisely what it was the railroad wanted:

We want to acquire the southeast quarter of the southeast quarter of section thirty six, township thirty six south, range four west, and will want to lease the balance of this section for the term of twenty five years with right for an additional twenty five years as provided in special statute. You are authorized to make formal application in behalf of the corporation Utah Parks Company. Will want this transaction to include understanding that we may, presently or later, transfer this property and leasehold to Los Angeles & Salt Lake Railroad Company or Union Pacific Railroad Company if we desire. [90]

Smith did as he was instructed on May 3, 1923, making formal application in the name of the Utah Parks Company with John T. Oldroyd, the State Land Commissioner. [91] The next day Smith sent Gray a copy of the application to Oldroyd. He noted that the Land Board had classified the section as grazing land, appraised at $2.50 per acre with a lease value of 25 cents per acre. It was Smith's impression that Oldroyd was indifferent to the railroad's proposal. On the morning of May 4 Oldroyd told Smith that the State wanted a much larger sum for the land. Smith had inferred from this that the Land Board would immediately reclassify and reappraise Section 36, so as to conclude the most advantageous bargain. [92]

Subsequently, Gray and Smith began to learn that the State was not merely interested in money. About May 10, State Senator Lunt, a member of the State Road Commission, informed Smith that State authorities feared the railroad would eventually exclude the general, nonpaying public from Section 36. Lunt himself favored an outright sale of all or part of the section to the Union Pacific but indicated to Smith that his hands were tied. [93]

At this stage of the negotiations Gray became exasperated. On May 14 he wired Smith that the Union Pacific would not be forced in the matter:

We will neither pay an excessive price and rentals nor will we take any other land than that we have decided upon, and if the matter is delayed and the hotels not constructed, the responsibility will have to rest where it belongs, which would certainly not be with us... [94]

Arbitration between the two parties reached its lowest point on May 16, when Smith, accompanied by Union Pacific System Park Engineer S. L. Lancaster, met with Oldroyd. Smith first tried to schedule a meeting at Bryce Canyon between Governor Mabey, interested State officials, and representatives from the railroad. This meeting appears to have taken place about the beginning of June, but it was probably not because of any effort Oldroyd made. In fact, during the May 16 meeting Oldroyd became flippant and at one point laughingly remarked to Smith and Lancaster that he, Oldroyd, had received suggestions that land in Section 36 be sold for $500 an acre, or as much as $100,000 for a 40-acre tract. Even at this price Oldroyd was insistent the State would never relinquish title to the southeast corner of Section 36, but would want the railroad to take its 40 acres "farther back." [95] Smith must have left this meeting clenching his fists.

During the next few days several influential members of the Salt Lake Chamber of Commerce and Commercial Club actively came to the railroad's support. [96] On May 26 the Board of Governors of the Commercial Club met with Mabey and Oldroyd. [97] These businessmen do not appear to have completely carried the day, but were likely instrumental in scaling down the State's demands. Unfortunately, no record is known to exist of what transpired between June and September. Gray's September 27 correspondence to Lovett as well as a lease, deed, and patent from the State, dated September 8 and 10; however, do spell out the compromise solution reached between the State and railroad.

Omaha, in the name of the Utah Parks Company, was granted a lease on 618.39 acres of Section 36—said lease to begin on January 1, 1923, and run for 25 years at $2 per acre per year. An option for an extension of 25 years was written into the lease. Leased land comprised the following parcels: (1) W1/2; (2) NE1/4; (3) W1/2 of SE1/4; (4) NE1/4 of the SE1/4; and (5) beginning at the SE corner of the SE1/4 of the SE1/4, running W 1320 feet, then N 970 feet, then E 970 feet, then N 970 feet, then E 350 feet, then S 1320 feet to the SE corner (18.39 acres). [98] The 18.39 acre parcel in the SE1/4 of the SE1/4 was deeded back to the State "for the support of the common schools of the grantee." [99] The 21.69 actually sold to the railroad, cost $540.25, that is $25 per acres. [100]

Both parties could be justifiably satisfied with the settlement. For its part, the Union Pacific now effectively commanded the situation at Bryce Canyon. An outlay of several hundred dollars was indeed a modest price to pay for this first rate opportunity. The annual lease fee was negligible. On the other hand, the State of Utah could claim its servants had carefully considered the situation, and what was done had been done for the long-term welfare of the State's citizens. Numerous conditions attached to the settlement do make clear that Omaha did plenty of compromising. The Union Pacific was required to provide ample space (as much as 40 acres) for public camping, and relinquish a right of way for a public road to the campground. [101] No timber could be cut on leased land without the States permission. [102] The State retained all mineral rights on the 21.69 acre plot it sold to the railroad. [103]

Syrett Camp

A more informal condition imposed by Salt Lake obligated the Union Pacific to reach "an amicable settlement with B. Syrett." [104] Omaha viewed this as a necessity anyway, since Syrett had filed on the closest water supplies to the SE corner of Section 36. It was also apparent to Smith that Syrett was well regarded in Mormon settlements near Bryce Canyon. It would make no sense to incur Syrett's enmity, and risk poisoning relations with the local populace. Smith accordingly opened negotiations with Syrett during the first week of June 1923. The Union Pacific offered to loan Syrett $2,500 at 6 percent interest, for the purpose of paying off debts Syrett had incurred to improve Tourists' Rest. Syrett would be allowed to operate Tourists' Rest until the Bryce Lodge was ready for occupancy. He would then be moved, at the railroad's expense, to another location within the SE 1/4 of Section 36, and issued a 5-year lease—presumably for the purpose of catering to motorists. In return for Syrett's assignment of water rights in Section 16, T. 37 S., the Union Pacific agreed to furnish Syrett's camp with free water "for such period of the year as the water supply is available." No concessions, such as the saddle horse operation, were offered to Syrett. [105]

Smith's proposal was pretty tight-fisted and Syrett likely saw it that way. Ruby thus attempted to use the State Land Commission as an intermediary, for the purpose of securing a better deal. Land Commissioner Oldroyd was not a personal friend of Syrett, but was prone to side with a fellow Utahn, especially one pitted against a powerful out-of-State corporation. Syrett presented the State Land Commission an inventory of property, valued by himself, at $15,500, inclusive of water rights. Howard Mann, a Union Pacific engineer, valued Syrett's property at $7,360, exclusive of water rights. [106] Smith was reluctantly drawn in. He proposed the sum of $9,000 as a fair offer, subject to Gray's approval. [107] Syrett had successfully managed to raise the ante in his favor, and decided to horse-trade for all the situation was worth.

Late in September a series of offers and counter-offers resulted in the Union Pacific's willingness to pay Syrett $10,000 for the latter's property and water rights. [108] Actually, the company was under pressure. Oldroyd, backed by State law, was withholding patent to land the railroad had purchased until either the company settled with Syrett, or deposited an amount with the Land Commission equal to the value of Syrett's improvements, as assessed by the State. The Union Pacific could resort to the latter method of settlement, but this would take time, and—more importantly—would not solve the water rights question. [109] Gray also had information from an unnamed source that the National Park Service had made an attempt to discourage Governor Mabey from facilitating the sale to the Union Pacific of any property. [110] Gray inferred from this that the National Park Service assumed Section 36 might someday be incorporated into a national park.

Syrett, too, may have been under some pressure to conclude agreement. He was in debt for improvements to Tourists' Rest, and it may be that the Panguitch bank wanted the debt liquidated. At any rate, a Bill of Sale concluded on September 25, 1923, settled the issue. Ruby and Minnie Syrett received $10,000 for enumerated property situated in the SE1/4 of the SE1/4 of Section 36, and water rights they held outside the section. [111] The Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railroad Company (LA. & S.L. R.R.) acted on behalf of the Union Pacific System.

Water Supply for Section 35

Syrett's water rights, as assigned to the Union Pacific System on September 25, 1923, consisted of Hopkins Spring and Shaker Springs—sometimes referred to as Weather Springs. Syrett's application to the State Engineer for Hopkins Springs was approved on January 9, 1923, bearing registration No. 8888. [112] Union Pacific Attorney George Smith noted that Hopkins Spring was located adjacent to Syrett's Tourists' Rest complex and informed Gray the spring did not amount to much. [113] Syrett s application for Shaker Springs was approved on June 25, 1923, and bore registration No. 9221. [114] Shaker Springs was located approximately 4-1/2 miles northeast of the proposed site for Bryce Canyon Lodge in Section 16, T. 37 S. It was considerably larger than Hopkins Spring and was the main reason the railroad wanted to buy out Syrett's water rights. When Syrett applied for Shaker Springs he probably intended to cover another spring in the immediate vicinity. Nevertheless, his description was defective, and Omaha thought questions might arise as to the claim's validity. The L.A. & S.L. R.R. thus made an independent filing on the spring to avoid future complications. [115]

On October 18, 1923, Union Pacific Resident Engineer, H. C. Mann, informed the Los Angeles office of the L.A. & S.L. R.R. that it would be necessary "to do some work" before December 31, in order to hold the water filing at Bryce. It appears Mann was referring to Hopkins Spring alone. Smith and Mann conferred on this issue, which implies the improvements were for the purpose of conforming to State law. Smith recommended that excavations be made for a head box around the spring. It would then be necessary to build forms and fill them with concrete or stone mortared into place. Smith estimated the project to cost between $500 and $1,000. On account of Bryce Canyon's severe winter climate, Smith said work should begin as soon as possible. [116] It must be assumed the project was completed late in the fall of 1923.

There is every reason to believe Union Pacific employees directly involved with the Bryce Canyon Lodge project were uneasy with the water supply acquired from Syrett. Consequently, additional sources of potable water were energetically sought after. In June 1925 the Union Pacific System, in the name of the L.A. & S.L. R.R., concluded a 25 year lease with W. J. and Elizabeth W. Henderson. For $50 per annum, the railroad acquired the use of a spring in the W 1/2 of Section 34, T. 36 S., whose rate of flow was gauged at 0.16 second feet of water, i.e., over 100,000 gallons per day. The lessor agreed to permit the use of sufficient land in the W 1/2 of Section 34 for the construction and maintenance of a pumphouse and pipeline. [117] Having concluded the Henderson Lease, the Union Pacific probably evaluated its water supply as adequate for years to come.

Reconnaissance for Bryce Canyon Lodge

Union Pacific's intent to construct major buildings in Zion National Park, Bryce Canyon, and Cedar Breaks made it necessary for the company to secure the services of a competent architect. During the early spring of 1923 National Park Service Landscape Architect Daniel P. Hull worked closely with an architect named Gilbert Stanley Underwood on the Yosemite Village project. Notwithstanding Underwood's limited success on the project, Hull was impressed with Underwood, [118] and undoubtedly recommended him to the Union Pacific System for use of the development of the Utah parks. [119]

Underwood, who had opened an office in Los Angeles in January 1923, [120] was invited to cone to Omaha, On the morning of May 1, 1923, he met with S. S. Adams and J. L. Haugh, Executive Assistants to President Gray. Adams and Haugh hired Underwood to plan the Zion Lodge. [121] They also asked Underwood to go over to Bryce Canyon and "look it over and make some suggestions." [122] It was understood that it the railroad was pleased with the results of Underwood's Zion project, he would shortly receive similar commissions. The next day Underwood started for Utah, accompanied by Union Pacific Park Engineer S. L. Lancaster and Randall L. Jones, the Union Pacific System's key liaison man in the Cedar City area. Enroute, Daniel Hull joined the group in Cheyenne. [123]

Underwood and the others arrived in Cedar City on the afternoon of May 4. They spent the night in Cedar City, then went on to Zion and spent the entire day there. The next morning, Sunday, May 5, 1923, the group departed for Bryce, and in Lancaster's words arrived there "in time to see the effect of the beautiful Sun Set." [124] Architect Underwood's first involvement with Bryce Canyon then, was on the Monday morning of May 6, 1923. He confined his efforts to the selection of a suitable site for the lodge. It appears that Underwood was made aware of the fact the plateau rim would likely be off-limits as a construction site. For this and less well known reasons, a site was chosen back away from the rim, yet close enough to make it readily accessible to lodge guests.

Lancaster was scheduled to meet Underwood in Los Angeles on May 21, 1923. [125] At that time the two presumably went over Underwood's preliminary sketches for Zion Lodge, and may have exchanged a few words regarding the proposed structures for Bryce Canyon and Cedar Breaks. Underwood and Lancaster did not meet again until early in July. [126] This conference—involving Underwood, Lancaster, and Hull—centered on Zion Lodge. During the working season of 1923 Architect Underwood's work at Bryce Canyon can be characterized as nothing more than reconnaissance.

Construction Program's Organization

During May 1923, with everything in a state of flux, the Union Pacific began to assemble and organize key personnel in its ad hoc construction team for the Utah parks. Howard C. Mann, a veteran Resident Engineer in the Union Pacific System, was transferred from the Columbia River bridge project to an office in Cedar City. He assumed a role as the principal technical figure in the entire Utah parks construction program. Mann was expected to handle estimates and expenditures, construction routines, and individual project organization. Samuel C. Lancaster, Union Pacific's roving Park Engineer, reported to Mann. Lancaster was responsible for choosing building sites and for landscaping. It would he his additional task to work with the National Park Service, Forest Service, and County and State Road Commissions regarding road work. Randall L. Jones had two primary responsibilities. He would be depended upon to secure local laborers and craftsmen. He was also to assist Mann as a supervisory architect. Jones, like Lancaster, reported directly to Mann. [127] As a team Mann, Lancaster, and Jones were destined to successfully inaugurate Union Pacific's major construction program for the Utah parks. The erection of all buildings in Bryce Canyon's "initial" building phase, between 1924-29, can be attributed to their efforts.

Materials for Bryce Lodge

As early as March 27, 1923, Lancaster sent Randall Jones to Bryce Canyon to investigate the possibilities of using local timber and rock for the construction of Bryce Lodge. [128] On March 29 Lancaster returned to Cedar City from St. George and made arrangements with the Forest Service for cutting timber to be used in the lodge's framework. The Forest Service charged $475 for this privilege. [129] Two days earlier Jones had contacted Charles Church and Fred Worthen to quarry suitable stone. For the sum of $143.65, Church and Worthen furnished 12 men and the necessary teams to haul stone. These men would be split into two 6-man gangs, with Church and Worthen acting in a dual capacity as foremen and powdermen. A quarry site was selected within 1-1/2 miles of the lodge site. Men were paid $3.20 per day, the foremen $5. [130]

Lancaster planned to accumulate lumber by means of a contract with Ruby Syrett and Owen Orton, dated March 30, 1923. These men were to provide 200,000 board feet of lumber at $27.50 per 1,000 feet. The contract also stipulated that as many slabs as needed for the lodge's construction be provided at 5 cents per linear foot. Each side of an individual slab had to be 1 foot wide, with its sides and ends squared. Syrett and Orton were to harvest all trees on National Forest land and agreed to have lumber and slabs properly piled on the lodge construction site by July 15, 1923. [131]

Lancaster justified these preliminary expenditures to Gray by explaining that construction during the 1924 working season could not proceed without properly seasoned timber. [132] Naturally, no timber could be used until the basement and foundations had been laid in stone. Lancaster estimated that shipping timber from the Northwest would add $20,000 to $30,000 to the cost of buildings proposed for Bryce Canyon and Cedar Breaks. He insisted that the best way to save money was to employ local people. This labor force could erect the lodge up to the laying of floors, the installation of plumbing, and the application of finished work. [133]

For some time Union Pacific's Executive Committee in New York was at pains to understand why Lancaster proposed to use so much stone in the Lodge's construction. On June 21 Lovett remarked to Gray that:

. . . stone-cutters are among the highest paid class of workmen and, furthermore, are not very plentiful . . . I confess it is rather hard for me to believe that attractive hotels can be built with stone at less expense than with lumber grown in abundance on our own lines no matter where the stone is found . . . [134]

In subsequent correspondence Gray pointed out to Lovett, and the rest of the Executive Committee, that the Utah parks buildings would be built "in the interior, far from the railroad." [135] Hauling lumber into Bryce by truck from Cedar City would also entail large expenses. Perhaps Gray's most persuasive argument was that stone work could be done at Bryce Canyon for 40 cents an hour. [136] Lovett, at least, was convinced and on July 30 communicated to Gray: "There is, of course, no doubt under the facts stated by you that the stone should be used in building these hotels." [137]

A few days earlier, in a progress report, dated July 15, 1923, Gray had told Lovett the foundation stone for Bryce Lodge was in the process of being quarried:

The stone is of such a nature that it breaks out from the quarry in the shape required for laying in the walls and it will not be necessary in any case to use a stone cutter upon it. The stone is to be laid up in a rough rustic style in cement and mortar, and can be done with the same common labor that is used for quarrying it. [138]

Gray further explained that timber at Bryce Canyon had proven to be of inferior quality—not at all suitable for the lodge's exterior finishing. Milling the requisite amount of lumber was slow because of the trees' small size. Gray figured the lodge's walls would be built up to the snowline with stone, above that with timber. He concluded by stating that actual construction would not begin until the spring of 1924 principally because of the area's poor roads. [139]

During a meeting of the Executive Committee, held in the first week of October, F. A. Vanderlip took an extremely negative view of the entire Utah parks venture. Vanderlip centered his criticism on two issues: the expense of individual buildings, Bryce Lodge among them, and what he termed the wretched condition of regional roads. [140] Lovett, himself, could not dismiss this criticism and asked Gray to fully advise him of the situation. Gray's reply to Lovett on October 6 was masterful and shows the President intended to stand firm during this period of crisis over the Utah parks program.

Gray adequately justified expenditures for rough materials. He explained that it was necessary to take good advantage of weather conditions. If the railroad decided not to build the lodge, this material could be used for the construction of camps. Gray emphasized his disagreement with Vanderlip's objection to the construction of lodges in Zion and Bryce Canyon. Gray cited that Omaha's Traffic Department had assessed that with camps alone the Union Pacific would be restricted to a "secondary class of travel." [141] This implied the railroad would not be able to secure any of the convention traffic, which then represented a significant percentage of rail traffic to Yellowstone and Glacier National Parks. The proposed return on camps alone also failed to justify a major advertising campaign for the Utah parks—a campaign considered absolutely necessary if the Union Pacific hoped to effectively compete with the first-class hotel accommodations available at Yellowstone, Glacier, and the South Rim of the Grand Canyon. [142] Gray did not ignore Vanderlip's remark about roads. He assured Lovett that Omaha's final decision to go ahead with development in Zion, Bryce Canyon, and Cedar Breaks was predicated on proper roads "and our [i.e. Omaha's] determination in this last respect has been very emphatically stated." [143]

Transportation Franchise

From early on Union Pacific officials were eager to launch a concerted effort for better roads in southwestern Utah. Yet, logic dictated that Omaha first secure the exclusive right to transport tourists in the area, and this meant dealing with the Parry brothers. Chauncey and Gronway Parry pioneered the tourist transportation industry in southwestern Utah and northwestern Arizona. [144] At an unknown date, the brothers had secured a certificate of convenience and necessity from the Public Utilities Commission of Utah. [145] This entitled them to operate a touring service to all scenic attractions within the State of Utah, but "with limitation as to time." [146] In the spring of 1917, William W. Wylie, his brother, Clinton W. Wylie, and the Parry brothers incorporated the National Park Transportation and Camping Company, [147] whose title changed shortly thereafter to the Zion National Park Company. [148] The National Park Service granted this company the exclusive privilege to maintain tourist camps in Zion, and to provide a tourist transportation service in and out of the park. The contract was finalized on September 6, 1917, but made the company's privilege retroactive to January 1, 1917. [149] In February 1922 a Memorandum of Agreement was drafted and signed by both parties, extending the Zion National Park Company's concession privileges for an additional year, to January 1, 1923. [150]

George Smith approached Chauncey Parry early in April 1923, that is, several months after the Parrys' Zion franchise had expired. At the time Chauncey Parry told Smith the brothers had no property, other than a few automobiles, automobile equipment, and a small garage. Smith was taken back when Chauncey told Smith the brothers expected to secure interest in whatever transportation scheme the Utah Parks Company proposed for the region. It was Smith's impression Chauncey based this aggressive position on reassurances he had gained from an earlier conversation with Samuel Lancaster. [151]

A dearth of documents on the franchise issue prevents an accurate appraisal of Omaha's position between April 1923 and March 1924—when the railroad did effectively secure the Parry's interests in southwestern Utah. [152] From a strick legal standpoint the brothers' position was indefensible. Their Zion franchise had expired, and the State's Public Utility Commission license indicated the touring service from Cedar City and Marysvale operated "with limitation as to time." It was probably this ambiguity written into the State license, however, and resistance on the part of the Public Utility Commission in Salt Lake City to clarify it, that forced the railroad into a contractual agreement highly attractive to the Parry brothers.

The 16-page agreement concluded on March 4, 1924, permitted the brothers to operate a regional motor transportation service under Utah Parks Company supervision. There were two key provisions in the contract, both generous to the Parrys. First, the brothers were to operate the transportation service for the Utah Park Company, until they decided to sell out completely. [153] Second, as long as the Parrys operated the service, in accordance with the provisions of the contract, they were to receive the combined annual salary of $5,000. [154]

The Utah Parks Company was legally required to purchase only vehicular equipment acquired by the brothers after February 15, 1924. [155] A description of these vehicles is not included in the contract, but it is known the Parrys operated some "White" touring cars. [156] On May 3, 1923, nearly a year before the Parry settlement, H. R. Child, President of the Yellowstone Park Transportation Company, strongly recommended to H. M. Adams, Union Pacific's Vice President of Traffic, that the Utah Parks Company purchase White touring cars for its operation:

. . . I do not hesitate to say to you very frankly that there isn't a car manufactured which can come anywhere near holding its own in any way with this White equipment, and you will make a mistake if you put in any other automobile to handle your tourists . . . [157]

Child's advice was passed from Adams to Gray, but it appears Gray decided to be selective. In the spring of 1925, the Utah Parks Company received permission from the Utah Public Utilities Commission to operate 40 touring cars, each having seats for 10 passengers. [158] Eight of the forty were new White "53's" with Scott bodies. [159] In 1929, Utah Parks Companies transportation fleet was augmented with the addition of 5 White "65's," capable of carrying 13 passengers. [160] The Whites did prove durable and were the backbone of Utah Parks Companies touring service until the outbreak of World War II.

REGIONAL ROAD DEVELOPMENT

(1923-25)

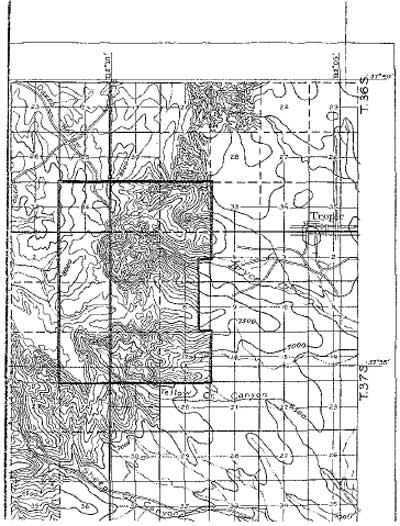

In 1922 two principal highways traversed the scenic region of southwestern Utah—both on a rough north-south axis. The "Arrowhead Trail," or Salt Lake City-Los Angeles Highway, entered from the north at Parowan, intersected Cedar City, and St. George via Anderson's Ranch. The distance from Parowan to St. George then was approximately 75 miles. An earlier but less important highway originated at Marysvale, and snaked southward some 70 miles to Hatch via Junction and Panguitch. Ten miles south of Hatch the road forked. Its more heavily traveled eastern branch ran approximately 50 miles through Alton and on to Kanab. The western branch intersected Glendale, Orderville, and Mt. Carmel then continued on to Kanab.

Bryce Canyon was practically equidistant from Marysvale and Cedar City. However, the road eastward from Cedar City to the Marysvale-Kanab highway junction had not yet been completed. In January 1922 a critical 8 mile gap existed just east of Cedar Breaks. There was an alternate 85-mile route between Cedar City and Bryce Canyon. It led from Cedar City north to Parowan, then ran northeast to junction with the Marysvale- Kanab highway at Orton Ranch, between Junction and Panguitch. This road was in reasonably good shape, but was impractical for the purpose of tying Bryce Canyon into a tourist loop with Zion and Cedar Breaks. At the time, Zion and Bryce were essentially inaccessible to one another. The only road which connected the Arrowhead Trail to the Marysvale-Kanab highway led from Laverkin, southeast of Anderson's Ranch to Fredonia, Arizona, 7 miles south of Kanab. This 63 mile stretch was regarded as the worst road in the entire region.

The Union Pacific knew that in order to make practical a tourist loop between Cedar City, Zion, Bryce, Cedar Breaks, and eventually the North Kin it would have to approach the improvement of the regional road system in a systematic way. Omaha had made clear its intention to refrain from direct investment in roads, [161] so the railroad could only work behind the scenes to galvanize the State of Utah, National Park Service, and Forest Service into action.

In October 1923, Union Pacific's first priority was to immediately get behind the State's proposed improvements for: (1) the Arrowhead Trail between Cedar City and Anderson's Ranch, and (2) the road eastward, between Anderson's and the south entrance to Zion via Rockville. [162] A first-rate road from Cedar City to Zion was in Omaha's estimation, essential for the establishment of a tourist circuit. The railroad had secured Salt Lake's backing to construct a road eastward from Rockville to Mt. Carmel, Once Mt. Carmel was linked to Rockville and Zion, the next logical step required an improved road from Mt. Carmel north, to junction with the eastbound Cedar City road at Divide. Later, attention to the road south from Mt. Carmel to Kanab would prevent the tortuous 50-mile stretch south from Hatch to Kanab. With an eye to the future development of the North Rim, the Union Pacific also intended to push for the construction of a road south from Rockville to Short Creek, near the Arizona State line.

Early in 1923, the State Road Commission had less than $200,000 at it; disposal. Even these funds were set aside as a revolving deposit to meet emergency situations. The 1921 State bond issues of $1,000,000 promised to be of some assistance. However, most of this money had already been spent. [163] Where, then, was support to cone from for an accelerated road program?

The basis for a solution rested with the provisions of the 1921 Federal Highway Act. It stipulated that the Federal Government would subsidize highway construction in individual States to the extent of 7 percent of the total mileage in each State. In 1923 total road mileage within Utah was approximately 24,000. Thus, some 1,600 miles of road could be made eligible for the "7 Percent Plan." According to the provisions of the Highway Act, Utah would receive 74 percent of all construction costs for the 1,600 miles designated. The State was required to foot the 26 percent balance, and pay for all engineering costs prior to actual construction. All plans, specifications and estimates were subject to the approval of the U. S. Bureau of Public Roads. To conform to federal specifications, roads had to be at least 18 feet wide, with a 3 foot shoulder on each side. The road had to be surfaced with gravel or a suitable paving material, such as cement. No grade could exceed a maximum of 6 percent. Bridges, culverts, and the like had to conform to a similar set of specifications. [164]

In October 1923 authorities of Utah's Road Commission applied to the Federal Government for approval of the following roads to be included in the 7 Percent Plan:

From Cedar City south to Anderson's Ranch, thence to Rockville and Zion National Park and eastward to Mt. Carmel, thence south to Kanab and on to the Arizona state line; also the new highway from Rockville south, crossing the new bridge to be built this winter [i.e. 1923] over the Virgin River, a distance of approximately 25 miles, to the Arizona state line. [165]

Dr. L. I. Hewes, Regional Director of the Office of Public Roads in San Francisco, approved this application, and the necessary papers were forwarded to Washington, D. C. [166] In January 1924, the Union Pacific learned the toads applied for had been approved by the Secretary of Agriculture and would be included in the Federal Aid System. Their estimated cost, based on Federal standards, was approximately $1,000,000. Neither Federal nor State funds were then available, so construction would proceed as the necessary appropriations were released. In March 1924, a $220,000 appropriation, voted by the Governor's Committee to the State Road Commission, reinforced the Union Pacific's optimism. This money was specifically earmarked for the Cedar City-Zion road, and Randall Jones thought it would complete the toad south from Cedar City as far as Laverkin. [167]

By April 1924 the road from Cedar City to Kanarra, a distance of 12.2 miles, had been contracted and work was in progress. No construction funds were available for the 4.5 miles from Kanarra to the Iron-Washington County line, but this stretch was regarded in good enough condition to stand up to all-weather driving. The 11 miles from the Iron-Washington County line to the foot of Black Ridge was financed and bids would soon be advertised. From this point for the next 7 miles to Anderson's Ranch the road was complete. The 7-1/2 miles from Anderson's to Laverkin were financed and bids would be advertised as soon as plans and specifications had been prepared. No money was available for the 24 mile stretch from Laverkin to Zion's southern boundary. [168] A Union Pacific survey conducted in January 1922 rated the road from Springdale to Wylie Camp in Zion as "60 percent." [169] There is no indication that in April 1924 either of the proposed roads running east and south from Rockville had as yet been started. Obviously, much needed to be done in Zion's vicinity.

In April 1924 the road from Cedar City to Bryce via Cedar Breaks was classified as a Forest Highway, with the exception of an 18 mile stretch from the Kane-Garfield County line north to Panguitch. [170] Forest Highways were not constructed nearly as well as 7 percent roads. Their main deficiency was an inability to stand up to heavy traffic, especially during inclement weather. By June 1924 approximately 20 miles of road from Cedar City to Midway—within 4 miles of Cedar Breaks—was in good shape by Forest Service standards. [171] Only 4 miles of road east of Cedar Breaks had not yet been completed. Even so, this section was under contract to a reputable firm, and its completion during June 1924 seemed assured. Forest Highway improvements from Divide north for 5 miles to the Kane-Garfield line began late in May 1924. Additional funds were shortly expected for Forest Highway improvements from Divide, 20 miles south to Glendale. No funds were available to improve a fair road from the Kane-Garfield line to Bryce Canyon Junction. Most of the 18 miles between Bryce Junction and Bryce Canyon were in excellent shape; however, a 6 mile stretch east of Red Canyon needed resurfacing. [172]

Financing the Cedar City-Cedar Breaks road for a distance of 23 miles proved a complex affair. It was estimated that $35,000 to $40,000 would be needed to widen the existing trail, surface it with a suitable material, and provide proper drainage. [173] Neither Federal nor State funds were available for this purpose, and the Union Pacific had, as a matter of principle, made clear its aversion to directly invest in roads. Fortunately for Omaha, the Forest Service was interested enough to subscribe 20,000. [174] At about the same time—September 1923—State Senator Lunt agreed to raise a bond issue of $5,000 in Cedar City. [175] However, only in February 1924, when the Commissioners of Iron County voted an appropriation of $10,000, was the project really made possible. [176]

By the spring of 1925 Omaha likely evaluated regional road development as uneven but promising. On the negative side, roads in and around Zion were only fair. The State project to extend a road from Rockville east to the Marysvale-Kanab highway had been flatly abandoned. Progress on the road from Rockville south to Short Creek was tangible, but roads in northwestern Arizona were only poor to fair. The Cedar City-Bryce Canyon connection via Cedar Breaks had received plenty of attention, but Union Pacific officials had no idea how well this critical road would stand up to heavy traffic.

Against these deficiencies long-term prospects appeared good. In November 1924 George FT. Dern became Governor of Utah, but was only one of a few candidates representing his party to be elected. This situation implied that Dern would make no significant changes in the State Road Commission Governor Mabey had put together. In his 1925 inaugural address, Dern defined his position on roads, emphasizing that the exploitation of Utah's scenic attractions depended upon the steady improvements of approach roads leading to them. Dern not only wanted to continue Mabey's expansionist road program, but stressed the need to institute a systematic State road maintenance plan. During the 1925 session, Utah's legislature responded to Dern's position on roads by increasing the State's gasoline tax from 2-1/2 cents to 3-1/2 cents per gallon. This measure almost immediately generated funds to reimburse citizens in Iron and Washington Counties who had advanced money to improve local roads. [177] Increased State aid, coupled with the steady flow of Federal funds into the 7 Percent Plan, foretold well for southwestern Utah's road system. The possibility of someday including the North Rim in Union Pacific's tourist circuit also received a boost in the fall of 1923, when the Governor of Arizona promised Utah Senator Lunt and Randall Jones that he would work strenuously to include the road south of Short Creek to Fredonia in Arizona's 7 Percent Plan. [178]

Zion-Mt. Carmel Road (1927-30)

The fascinating story of Zion-Mt. Carmel Road properly belongs in a general history of Zion National Park. It is, however, well worth noting its singular importance to the development of Bryce Canyon. The extension of a road from Rockville east to the Marysvale-Kanab highway was never pursued by the State with enthusiasm. In 1927 a more attractive and challenging proposal envisioned the construction of a tunnel through the 10,000 foot range which bisects Zion on a north-south axis. A road from the tunnel's eastern end to Mt. Carmel could then be built to connect the two main north-south highways in southwestern Utah.

On July 4, 1930, after 3 years of arduous work brilliantly channeled by engineering excellence, the Zion-Mt. Cannel tunnel was dedicated. Its 5,600 feet had been blasted through solid rock, using engineering techniques never before attempted. [179] Inclusive of the tunnel, approximately 8-1/2 miles of road within the park were linked to a 16-1/2 mile section, running from the park's eastern boundary to Mt. Carmel. Road costs within Zion amounted to $1,440,000 with $503,000 spent to construct the tunnel alone. All of this money was taken from National Park Service appropriations. The 16-1/2 mile section from Zion to Mt. Cannel cost $456,000 of which the Federal Government paid $358,000 and the State paid the rest. [180]

Completion of the Zion-14t. Carmel Road reduced the distance between Zion and Bryce from 149 to 88 miles. Traveling time from Zion to the North Rim was dramatically shaved by a third. For the first time, Zion, Bryce, Cedar Breaks, and the North Rim were effectively tied together. The Union Pacific obviously stood to gain from this situation, but had it not been for the perseverance of its agents, there would have been little chance for an accelerated road program during the 1920s. Construction of the Zion-Mt. Camel Road had one other significant result: the very creation of Bryce Canyon National Park in September 1928. (See section under NATIONAL PARK STATUS.)

|

| Illustration 4. Site of the former Denver and Rio Grande Railroad Depot in Marysvale, Utah. July 30, 1979. (Nicholas Scrattish) |

|

| Illustration 5. Lund, Utah. July 28, 1979. (Nicholas Scrattish) |

|

| Illustration 6. Lund, Utah. East and west sidings off the main line merge at this point into the single track to Cedar City. July 28, 1979. (Nicholas Scrattish) |

|

| Illustration 7. Union Pacific Depot, Cedar City, Utah. July 28, 1979. (Nicholas Scrattish) |

|

| Illustration 8. Chauffeur's Lodge (Union Pacific), Cedar City, Utah. July 28, 1979. (Nicholas Scrattish) |

|

| Illustration 9. Commissary Building (Union Pacific), Cedar City, Utah. July 28, 1979. (Nicholas Scrattish) |

|

| Illustration 10. El Escalante Hotel, Cedar City, Utah. Early 1930s. (Nebraska State Historical Society) |

|

| Map 1. Regional Road Map, circa 1922. (Record Group 79, Records of the National Park Service, National Archives Building, Washington, D.C.) |

|

| Map 2. Bryce Canyon National Monument, 1923. (Record Group 79, Records of the National Park Service, National Archives Building, Washington, D.C.) |

|

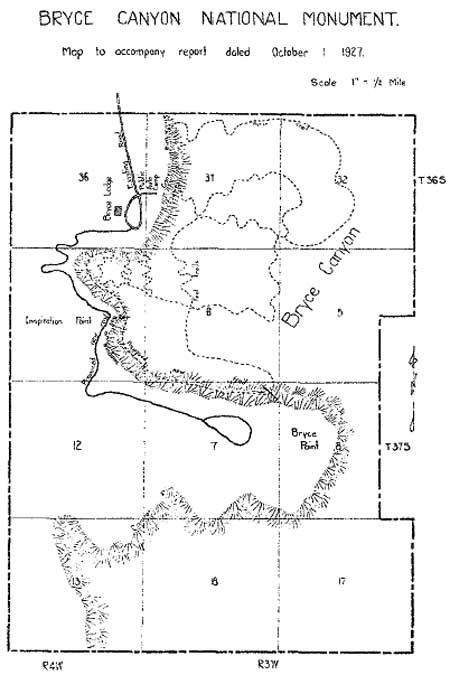

| Map 3. Map of Bryce Canyon National Monument, 1927. (Record Group 79, Records of the National Park Service, National Archives Building, Washington, D.C.) |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

brca/hrs/chap3.htm

Last Updated: 25-Aug-2004