|

Casa Grande Ruins

Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, Arizona: A Centennial History of the First Prehistoric Reserve 1892 - 1992 |

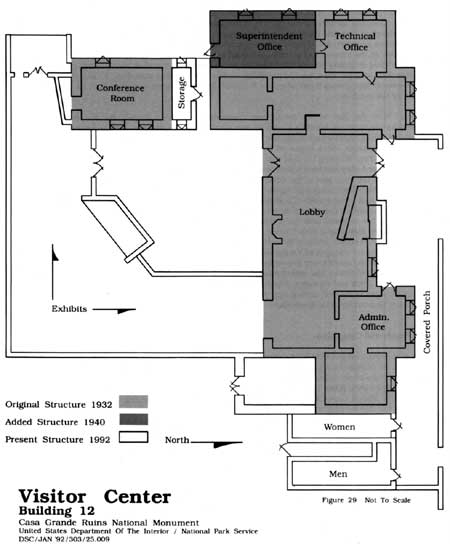

|

APPENDIX F:

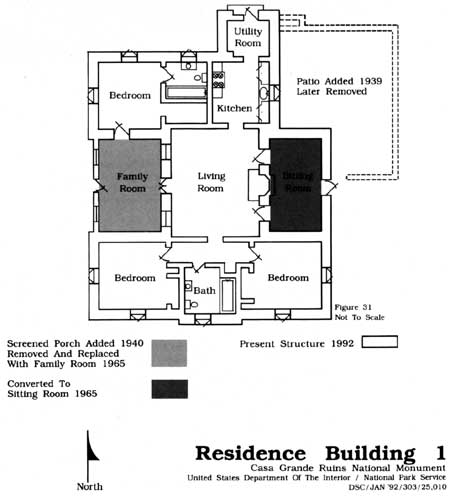

CASA GRANDE RUINS NATIONAL MONUMENT: NATIONAL PARK SERVICE BUILDINGS

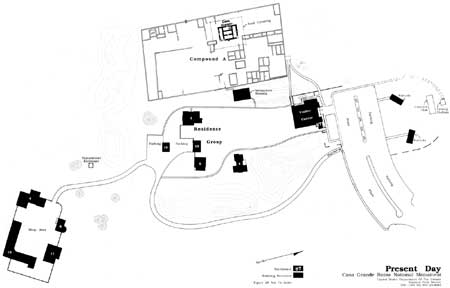

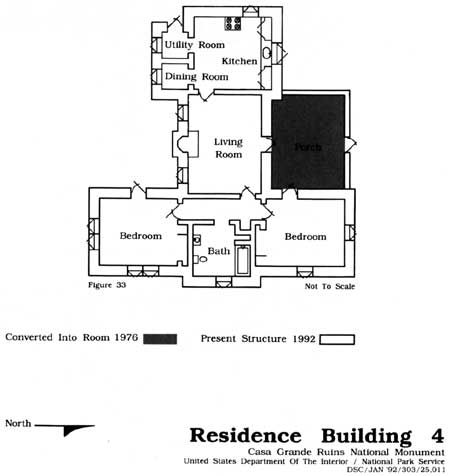

Construction programs at Casa Grande were a sometimes thing. Development under the General Land Office administration was almost non-existent. That agency's only expenditure was to place a roof over the Great House in 1903. The General Land Office commissioner even told Frank Pinkley that he would have to build a residence at his own expense. Money to provide for employee and visitor facilities did not become available until after the National Park Service acquired the property in August 1918. Even then, construction funds were rarely available in the 1920s. Onky two structures, a museum and a residence, were built in that decade. These buildings have since been removed. Most of the construction funds came during the depression era of the 1930s. The last development period, in the early 1960s, came from the National Park Service Mission 66 program (figure 28).

Construction at Casa Grande Ruins National Monument has, for the most part, been accomplished by following a plan developed by Thomas Vint and Frank Pinkley in 1928. Vint thought that buildings should be grouped together on a functional basis. Consequently, a picnic area with ramadas was developed in a separate location from the administration/museum building (visitor center). Employee residences were built in another area, and the maintenance facilities were developed in a third compound. Convenience dictated the location of utility structures such as the pumphouse and the wall around the electric transformer. The decision to erect a protective roof over the Great House followed a ruins preservation plan. All of the buildings had the same Southwest architectural design of a modified Pueblo style. Except for the protective roof over the Great House, each grouping or compound of buildings will be considered as an entity when considering their historical significance for the purpose of nominating them to the National Register of Historic Places. Changes to the picnic area, administration/museum building, pumphouse now monument library, and the employee residence compound have resulted in alterations that detract from their historic appearance. As a result, only the maintenance grouping, and electric transformer enclosure have retained their historic integrity and will be nominated to the National Register. These structures were constructed by the Civilian Conservation Corps between 1938 and 1940. In addition the 1932 protective roof over the Great House will be nominated to that listing.

|

|

Figure 28: Present Day Park Map (click on the above image for an enlargement in a new window) |

The Picnic Facility

A picnic facility has been located on the site of the current picnic area since late 1918. Until 1956, the location also contained a campground. In both 1932 and 1933 the picnic area was expanded with ramadas, tables, and fireplaces (see figure 24). By 1956, because of a desire by regional personnel to discourage picnicking, the picnic site was drastically reduced in size. It remained in that reduced condition until the 1976-77 period. At that time, it was remodeled with new ramadas set over concrete slabs. Consequently, the current picnic site with its modern-day facilities has no historic integrity. [1]

The Administration/Museum Building (Visitor Center)

The administration/museum building, now named the visitor center (Building 12), was completed on January 5, 1932 at a cost of $9,166.20. Thomas Vint of the Park Service San Francisco Field Office had originally designed the structure to be built as a square with an open center, but the appropriation was only sufficient to complete the front part of the square. The building had a modified Pueblo architectural style. Built on a concrete foundation, its twenty-four-inch thick adobe walls had stucco on the exterior and lime plaster on the interior. Its flat roof was hidden behind a low parapet wall (figure 29). The major part of the building originally housed offices for the Southwestern Monuments headquarters personnel until October 1942 and for the Casa Grande Ruins National Monument custodian. In December 1940, the Southwestern Monuments Superintendent, Hugh M. Miller, had a private office built on the southwest corner of the structure. [2]

Almost from the day of its completion, monument personnel longed for the day when the administration/museum building would be expanded to the size that Mr. Vint had initially proposed. Finally, in 1963 Congress authorized the funds to increase the visitor center's size to a square building with an open center. Work began on the addition in late 1963. When it was completed in 1964, the restroom building (Building 13) to its rear had been incorporated into the structure for a conference room and an L-shaped wing had been added to achieve the hollow square building (figure 29). Restrooms were relocated into the front part of the structure with entrances off the new, covered porch which ran the length of the building's north side (figure 30). This expanded area, which provided more than double the exhibit space, had exterior walls of both adobe and concrete block covered with stucco. A pole ceiling was built into the lobby. The visitor center retained its modified Pueblo architecture. Cyclical painting maintenance has occurred with the exterior walls coated with a texturized paint in 1976, and 1986. A Dunn-Edwards Elastomeric Wall Coating in a new color termed "Casa Grande Ruins" was applied to the Visitor Center's exterior walls in 1991. Interior walls are painted every two years. In 1975 a one-inch urethane foam coat was applied on the visitor center roof. Maintenance called for painting it with a latex protective coat and reseal every five years with a new foam covering every twenty years. Problems have developed with the foam coat with the result that a plan has been developed to re-roof the building by removing the foam and replacing it with a built-up composition roof. Because this building has been greatly changed in the past twenty-nine years to the extent that it no longer retains its historic integrity, it will not be considered for nomination to the National Register of Historic Places. [3]

|

| Figure 29. |

|

| Figure 30: The Visitor Center |

The Residential Compound

This area, when completed in 1934, contained five buildings for employee housing as well as a storage structure. All of these buildings had a modified Pueblo architectural style. The first two buildings on the site comprised a museum building reconstructed in 1925 and a ranger residence built between November 1928 and April 1929. When Thomas Vint, the chief landscape architect of the Park Service's San Francisco Field Office, visited Casa Grande in December 1928, he advocated grouping buildings on a functional basis. He felt that the 1925 museum could be converted to a residence and, along with the nearby ranger quarters then in the process of construction, could form the first buildings of a residential compound. The original museum building became a residence in January 1932 with the completion of the new museum. This structure (Building 2) was demolished in July 1966. The 1929 ranger residence (Building 3) was removed in January-February 1965 together with much of the compound's partial adobe wall enclosure.

The three remaining residences and a garage were built in 1931 and 1934. Each of these buildings has been modified over the years. These modifications, combined with the removal of two of the compound quarters and the partial surrounding adobe wall, have changed the compound's historic appearance with a resultant loss of integrity. Consequently, the remaining buildings will not be nominated to the National Register of Historic Places. [4]

Building 1, an eight room residence, was erected in 1931 as living quarters for the Superintendent of the Southwestern Monuments (figure 31). Since 1975, it has been converted to a seasonal dormitory (figure 32). Built at a cost of $5,328.01, it now contains an overall 2,097 square feet. The quarters has adobe walls set on a concrete foundation. The walls rise above the flat roof to form a parapet. They have stucco on the exterior with plaster on the inside. In 1939 a patio with surrounding adobe wall was added (see figure 31). The following year a screened porch was constructed to the center of the west side. A major rehabilitation occurred to the quarters in 1965. The 1939 patio with its surrounding wall was removed. Two windows and a door on the west were replaced in the same year along with the removal of the screened porch. Also in that year, a family room with a built-up roof was constructed in place of the porch. On the opposite side of the building, a sitting room was added (see figure 31). In 1970 a one-inch thick layer of urethane foam was put on the roof and covered with two coats of white, styro acrylic emulsion for a vapor seal and to protect the foam from sunlight. This foam roofing material proved unsatisfactory. In 1983 the foam was removed and the roof cleaned to its original deck. The new roof consisted of Red Rosen paper for a moisture barrier. It was covered with an all weather base felt called "Flintkote." Next, a three-quarter inch fesco insulation board set in asphalt was placed over the felt. It was followed by forty pound Flintkote set in asphalt. Two layers of asbestos fifteen pound finishing felt came next. Ninety pound roofing was applied to the walls as flashing and the seams were sealed with number 204 plastic cement and fiberglass tape. New four by eight inch drains were installed. Finally, the roof received a covering of number 220 fibered aluminum. In 1990 the exterior walls were painted with Flexon 701. [5]

|

| Figure 31. |

|

| Figure 32: Building 1 — Former Southwestern Monuments Superintendent's Residence. Completed in 1932, it has been modified in 1940 and 1965. The building now houses a seasonal dormitory. |

Building 4, a six room quarters with an overall 1,620 square footage, was built in 1934 at a cost of $4,949.25 (figure 33). Like the other structures, it has a modified Pueblo architectural style. The adobe walls are set on a concrete foundation and have a parapet rising above the flat roof. They are stuccoed on the exterior with plaster on the interior (figure 34). In February 1976, the front porch was removed and replaced by an enclosed room. Like building 1, a urethane foam roof was put on the structure in 1970. It was removed in 1983 and given the same treatment as described for building 1. In 1990 the exterior walls were painted with Flexon 701. [6]

|

| Figure 33. |

|

| Figure 34: Building 4 — Ranger Residence |

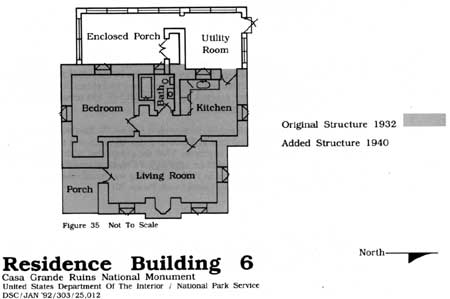

Building 6, a four room residence with an overall 1,217 square footage, was constructed in 1931 for use by the Casa Grande custodian (figure 35). The quarters cost $3,137.20. It has the same architectural style and type of construction as the other quarters (figure 36). Originally, this small residence had three rooms and a brush ramada on the west side for a porch. The brush ramada was thought to be a fire hazard, so it was removed with CCC labor in 1940 and replaced by a "service" porch. In early 1965 that porch was removed and replaced by an enclosed room. Thus the residence came to have four rooms. Its roof received the same treatment in 1970 and 1983 as the other quarters. In 1990 the kitchen was remodeled and the exterior walls were covered with Flexon 701. [7]

|

| Figure 35. |

|

| Figure 36: Building 6 — Ranger Residence |

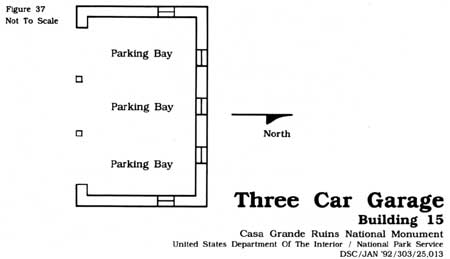

Building 15 was erected in 1931 for use as a tool and implement shed (figure 37). This modified Pueblo style structure has an overall 830 square feet and cost $1,528.30 to build. Its walls and foundation are made of the same material as the other monument structures. With the completion of the maintenance compound by 1940, this building was no longer needed for storage. As a result, it was converted into a laundry and storage facility for the resident employees. In 1963 the building was transformed into a three-car garage (figure 38). In 1990 the exterior walls were painted with Flexon 701. [8]

|

| Figure 37. |

|

| Figure 38: Building 15 — Originally a tool and implement shed when it was built in 1931. It became a laundry in 1940 and was modified to a three car garage in 1963. |

The Maintenance Compound

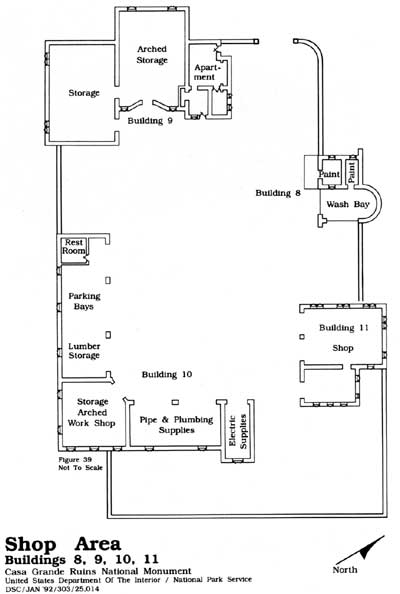

This walled area, located south of the employee quarters, contains four buildings which were constructed between December 1937 and January 1940 by the Civilian Conservation Corps (figure 39). As early as December 1928, Thomas Vint foresaw the need for a maintenance compound, but he mentioned only two buildings. By the mid-1930s Frank Pinkley desired a larger complex because he wanted to have a maintenance capability not just for Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, but for all the units that he administered in the Southwestern Monuments. Consequently, Pinkley arranged to have a CCC spike camp established at Casa Grande in November 1937 with enough manpower to construct the maintenance facility. This walled compound of maintenance buildings, built in a modified Pueblo style, has had few changes since its construction. As a result, it has historic integrity and will be nominated to the National Register of Historic Places.

|

| Figure 39. |

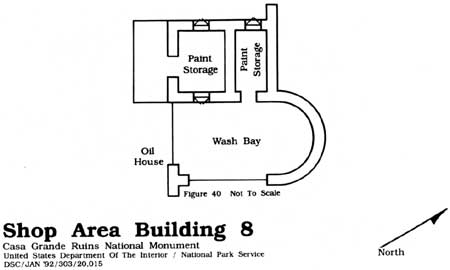

Building 8 served as an oil house with a covered wash rack extension on its south side. As CCC project number 52, it was begun in June 1938 and completed in January 1939. Materials cost $800.00. This rectangular building of 666 square feet has two divisions — a building and a covered wash rack (figure 40). The building portion has two storage areas for paint and oil. This single story building has adobe walls on a concrete foundation. Its walls were stuccoed over two- by two-inch wire mesh with "bitudobe" on the exterior and plaster over metal lath on the interior. The building has a reinforced concrete roof (originally covered with thirty pound mopped on felt), while the wash rack is covered with a corrugated iron roof supported by a wood frame which, on its outer side, rests on adobe covered piers (figure 41). The coping consisted of concrete block cast in place. Concrete slabs make up the floor. Double built-up pine doors with a herringbone pattern give access from the front, while a pine door permits entrance from the covered wash rack. These doors were faced with metal on the inside. The windows consisted of steel sash and frames. A semi-circular end wall is located on the structure's northeast corner. This end wall forms part of the surrounding compound wall. A concrete pad, on which a gas pump was placed, extends from the front of the building. A 575 gallon gas tank was buried beneath the pad in September 1938. By 1950, the gasoline tank was no longer used. In 1985 it was filled with water and in 1990 it was removed. In March 1976 the exterior walls were wet sandblasted and a texture coating of Flexon 701 applied. It matched the previous color. The structure was reroofed in 1988. In 1991 the exterior walls were power washed, coated with a primer, and painted with Dunn-Edwards wall coating. [9]

|

| Figure 40. |

|

| Figure 41: Building 8 — Oil house with wash rack. This structure now serves as a storage place for more flammable material. |

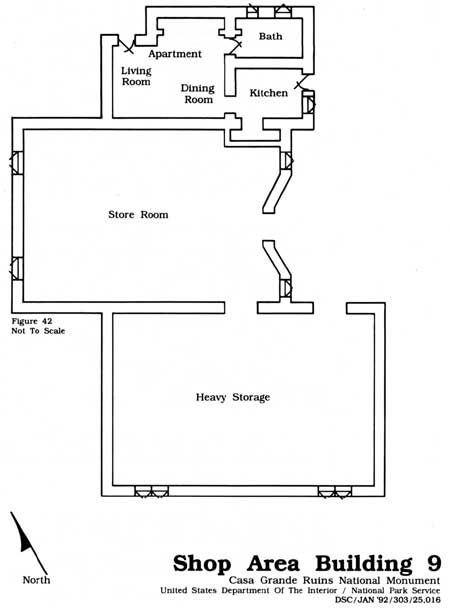

Building 9, a combination warehouse, office, watchman's quarters, and bathroom, was built in two phases. The first phase began on February 24, 1938 and was completed in January 1939. A second part or south wing was started in March 1939 and finished in August 1939 (figure 42). Materials cost $1,17924. This single story L-shaped building has adobe walls built on a concrete foundation. It has concrete slab floors. A parapet wall or coping of concrete block cast in place rises slightly above the roof. The walls were covered on the exterior with bitudobe over two-by-two inch wire mesh. Inside, the walls of the warehouse were plastered, while those of the office were plastered and painted. Interior walls in the watchman's quarters were plastered and calcimined and those of the bathroom were plastered and enameled. Three- ply paper layered on Celotex insulated board covered the wood frame roof. The original windows were wood frame with wood sash. Double pine doors with a herringbone pattern give entrance to the south section. Partly glazed double doors open into a storage area in the other part of the L-shape. The office and quarters portion had two doors on the front and one on the side. Between December 28, 1964 and February 25, 1965, the watchman's quarters, bathroom, and office areas were remodeled into an efficiency apartment. The wood frame windows were removed in this section and replaced with aluminum sash ones. In March 1976, the exterior walls were wet sandblasted and texture coated with Flexon 701. The building was reroofed in 1988. In 1991 the exterior walls were power washed, coated with a primer, and painted with Dunn-Edwards Elastomeric Wall Coating. [10]

|

| Figure 42. |

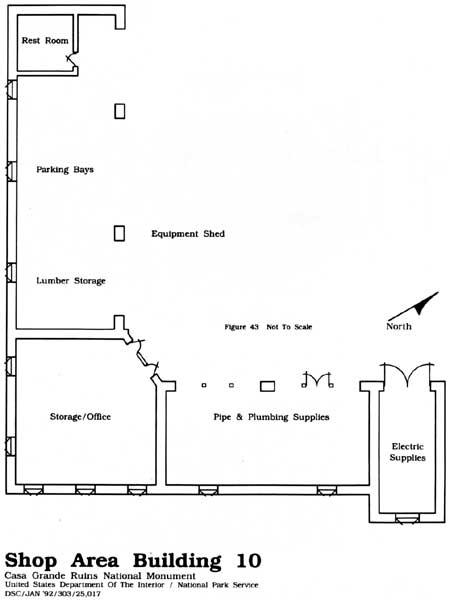

Building 10, an equipment building, was built in two phases. Construction of the first part, three open bays, began in October 1938 and was completed in March 1939. Work on an addition, which gave the structure an L-shape, began in March 1939 and was finished in November of that same year (figure 43). The second area consisted of three bays and an artifact storage area in the southwest corner. This single story building has adobe walls built on a concrete foundation (figure 44). It has earth floors except in the artifact storage part (later office) where a concrete slab was laid. A parapet wall or coping of concrete block cast in place rises slightly above the roof. The walls were covered on the exterior with bitudobe over two-by-two inch wire mesh and plastered on the interior. A wood frame roof, carried on open web steel trusses, originally had a covering of three-ply paper layered on Celotex insulated board. The three open bays of the north/south section connect in the corner with what was once the artifact storage room that later became an office. Partly glazed double doors permit entrance to the corner room. Two glazed transoms are situated over those doors. Three bays also occupy the east/west section of the building. Two of these bays were originally open, but have subsequently been enclosed. The third bay, which is approximately three feet higher than the other portion of the building, has double oversized pine doors that contain a herringbone pattern. A restroom was built into the northwest corner in 1968. The structure's exterior was wet sandblasted in 1976 and texture coated with Flexon 701. It was reroofed in 1988. In 1991 the exterior walls were power washed, coated with a primer, and painted with Dunn-Edwards Elastomeric Wall Coating. [11]

|

| Figure 43. |

|

| Figure 44: Building 10 — An L-shaped equipment storage building. |

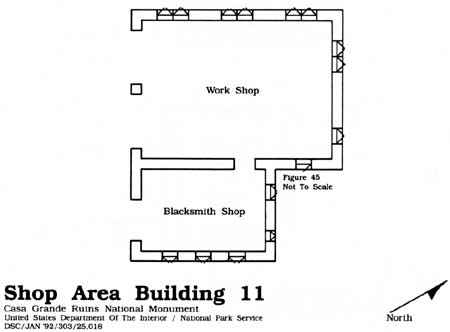

Building 11, a single story shop and blacksmith shop, was the first and last building of the maintenance complex to be erected (figure 45). It, too, was constructed in two phases. As their first construction project at Casa Grande, the CCC workmen began to build the shop part of the building in December 1937 and completed it in January 1939. This section was built in the same manner as the other maintenance structures with adobe walls on a concrete foundation. A parapet wall of concrete block cast in place rises slightly above the roof. Again, the exterior walls were covered with bitudobe over two-by-two inch wire mesh and the interior walls were plastered. It has a concrete slab floor. The shop section contains two bays with sliding pine doors that each hold three windows of two over two glazing. Elsewhere in the building, the windows are wood casement. Beginning in October 1939 an addition was built on the shop's south side to house a blacksmith shop (figure 46). That segment was finished in January 1940. It was constructed in the same manner and using the same materials as the shop. The roof line of the blacksmith shop portion is approximately one foot lower than the shop roof. A sliding pine door permits access to the blacksmith shop from the west. This structure also had wet-sandblasting followed by a texture coating of Flexon 701 of its exterior walls in 1976. Like the other maintenance buildings, it was reroofed in 1988 In 1991 the exterior walls were power washed, coated with a primer, and painted with Dunn-Edwards Elastomeric Wall Coating. [12]

|

| Figure 45. |

|

| Figure 46: Building 11 — Originally a shop and blacksmith shop which now houses a shop facility. |

The maintenance area was enclosed with a six-foot high, 417 lineal foot adobe wall. It was covered with bitudobe over two by two inch wire mesh. This wall, which was topped with concrete coping, was constructed between mid-1938 and December 1939. A gateway with posts was completed in the northwest corner of the wall in August 1938. In some areas this compound wall formed the back wall of the buildings. [13]

Additional Civilian Conservation Corps Work

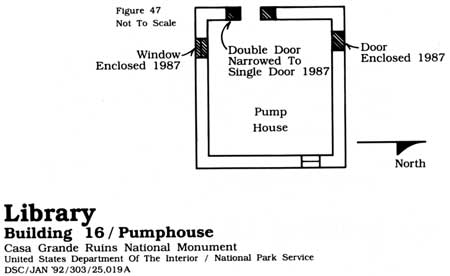

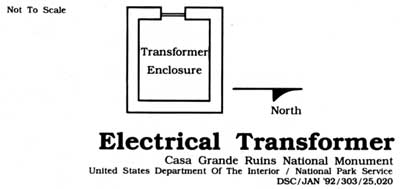

Along with the maintenance compound, the CCC constructed an adobe pumphouse and adobe enclosure walls around the electrical transformer. Both were completed in the modified Pueblo architectural style. The transformer walls retain their original appearance and will be nominated to the National Register of Historic Places. In 1987 the exterior of the pumphouse was modified. This change in its historic appearance excludes it from consideration for placement in the National Register.

Building 16, a pumphouse located just south of the employee quarters, was begun by the CCC laborers in August 1939 and completed in December of that year (figure 47). This 440 square foot structure was built of adobe walls on a concrete foundation (figure 48). As with the other CCC constructed buildings, the exterior walls were covered with bitudobe over two-by-two inch wire mesh. Interior walls were plastered. A parapet wall rises slightly above the roof. The pumphouse had a poured concrete floor. Its windows were wood frame with wood sash. The entrance contained a wooden door which was removed in 1987 and enclosed. Double metal doors on the west were also removed in 1987. That area was partly enclosed and a single metal door put in the wall. At the same time the south window was removed and enclosed. When the monument was connected to the Coolidge water supply in 1952, this building was no longer used. According to the Mission 66 plan, the structure was slated to be removed. In 1960, however, the building was converted to a storage facility. It was remodeled in 1989 into the monument library. In 1976 the exterior walls were wet-sandblasted and given a texture coat of Flexon 701. In 1991 the exterior walls were power washed, coated with a primer, and painted with Dunn-Edwards Elastromeric Wall Coating. [14]

|

| Figure 47. |

|

| Figure 48: Building 16 — Monument Library. Originally constructed as a pump house in 1939. In 1960 it was converted to a storage facility. Remodeled into the monument library in 1989. |

Adobe enclosure walls were built around the electrical transformer by the CCC workforce in November 1938 (figure 49). These nine foot, six inch high walls, located between the employee quarters and the maintenance facility, cover a 155 square foot area. They were covered with bitudobe over two-by two-inch wire mesh and are capped with concrete coping. There are 12,500 volts coming into the transformer and 440 volts leaving it to the monument. [15]

|

| Figure 49. |

Ruins Shelter Roof

Although this 1932 shelter roof has no unique engineering or architectural features because it was constructed by using common steel frame techniques of the day, it has historical importance. Even though it was not the first roof to cover the Great House, this roof represents early National Park Service preservation efforts. Consequently, this structure will be nominated to the National Register of Historic Places.

By the mid-1920s the original shelter roof had begun to deteriorate. Although Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. designed a new roof in 1928, a design competition was soon held. It was not until 1932, however, that funds were appropriated to build the roof. Consequently, the Chief National Park Service landscape architect, Thomas Vint, became involved with the roof design. He wanted a distinctive roof, not one that would blend with the ruins. The National Park Service Director, Horace Albright, however, advocated that Olmsted's design be followed. Olmsted planned a structure with a hipped roof supported on leaning posts that was secured with guy wires much like the ropes used on a circus tent. He designed the roof with these wires because he feared that the upward lift of the wind on such a structure could damage it and the ruins. [16]

On April 28, 1932 the National Park Service Washington office notified the San Francisco Field Office that funds were available to construct the ruins shelter. Soon thereafter, the design was finalized. For the most part, Vint followed Olmsted's plan with the exception that he omitted the guy wire arrangement and he made some changes in the cantilever trusses that supported the eaves. Otherwise, the hipped roof supported by leaning posts followed Olmsted's proposal. Allen Brothers, a bridge construction firm from Los Angeles, won the bid. That company sublet the excavation and footings to Clinton Campbell and the steel fabrication to the Virginia Bridge and Iron Company of Birmingham, Alabama. Campbell began work on September 19 to excavate for the footings. Soon thereafter, a railroad car of cement arrived along with 126 yards of gravel and sixty yards of sand. Campbell used that material to pour the footings. Each of the four, ten foot long footings was twelve feet square at the base and tapered to four foot, six inches at the top. The footings weighed seventy-eight tons each and had eight, one and one-half inch diameter bolts, twelve feet long imbedded in the concrete. The roof support columns were attached to these bolts. [17]

Before construction began on the new roof, the old 1903 shelter roof was removed and a temporary timber shelter erected over the Great House. The old roof was in such poor condition that it would not have protected the ruins from potential damage during construction. [18]

|

| Figure 50: Ruin Shelter Roof. Constructed in 1932 to protect the Great House. |

When the new ruins shelter was completed on December 12, 1932, it stood forty-six feet from the ground to the eaves. Four slanted columns of round, welded steel pipe with interior steel reinforcing supported the roof. A two-way steel truss system covered the entire bay of the hipped roof. The shelter roof had an overall dimension of ninety-eight feet north and south and eighty-two feet east to west. It had a slope of three inches in each foot. Its roof ridge was approximately fifty-eight feet, eleven inches above the ground. A copper louvered ventilator was designed for the roof ridge to reduce upward wind pressure. The highest point of the structure, the top of the monel metal ball used for a lightning rod, reached sixty-nine feet, three inches above the ground (figure 50). Its roof was covered with transite sheets of corrugated asbestos-cement material. Each sheet measured forty-two inches wide and six-feet, six-inches long and weighed ninety-six pounds. The sheets were fastened with bolts every twelve inches along each purlin. In addition the roof incorporated four corrugated glass skylights which measured six-by sixteen-feet on the short roof side and six-by thirty-two-feet on the long side. Lightning protection came from an eight- inch monel metal ball atop a two-foot vertical section of Bakelite tubing insulation which was screwed to an eight-foot hollow steel tube fastened to the center of the ridge. A three-eighths-inch strand copper cable passed through the tube from the ball and followed the hip rafter to the southwest corner column. The cable ran through that column and the concrete footing to be grounded to a one yard square, twenty-two gauge copper plate buried fifteen feet below the surface in a bed of charcoal and rock salt. Each of the four columns were grounded in a similar manner. The roof drainage was accomplished by an eight-by ten-inch copper gutter forming the roof cornice. Two, six-inch copper downspouts connected with two six-inch wrought iron downspouts placed inside the two west columns. Water ran from there through two, eight-inch vitrified clay pipes in the ground to a low point sixty feet west of the compound. [19]

In the final construction report, the National Park Service structural engineer, Edward Nickel, who supervised much of the shelter's construction, described the care involved in the roof's design and construction. What he wrote described the modifications that Thomas Vint made to Olmsted's design. Vint's concern was that, although a roof would have an architectural value of its own, it should be designed to contrast with the Great House ruin and not blend with it. It should not detract from the ruin that it was intended to protect. Nickel stated that,

In designing the various structural members consideration was given to the architectural proportions so that the final appearance of the steel frame would be the best possible. For this reason angle sections were used in place of channels in the trusses, with the least dimension vertical, resulting in the desired appearance of lightness to contrast with the massive adobe walls.

Greater symmetry and architectural beauty was obtained in the steel frame and bracing, by using sections of similar overall size where possible. [20]

Upon completion, the shelter was painted a sage green to harmonize with the mountains and vegetation as well as provide a contrast with the ruin's walls. In subsequent years, little maintenance has been required for the shelter beyond periodic repainting. In 1955 some cracks, that had appeared in the support columns, were welded. The last coat of paint, applied in 1989-90, changed the shelter color from sage green to light tan. [21]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

cagr/adhi/appf.htm

Last Updated: 22-Jan-2002