|

Casa Grande Ruins

Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, Arizona: A Centennial History of the First Prehistoric Reserve 1892 - 1992 |

|

CHAPTER VI:

EDUCATING THE PUBLIC — PUBLICIZING AND INTERPRETING THE MONUMENT

Success at Casa Grande required more than construction of buildings and protection of the ruins. The first non-resident custodians conceived of their job as ruins protection and not as one to develop, promote, or interpret the monument. Frank Pinkley, who arrived in 1901, had other ideas. To him, the purpose of establishing the reservation was not just to protect the prehistoric remains found there. Pinkley also sought to publicize the monument and educate the public about the ancient culture that had occupied the site. An enlightened population would then not only know about the prehistoric past, but could serve as a support group for Casa Grande and other archeological sites.

Pinkley devised a number of means to attract people to Casa Grande as well as methods to educate them. His first thoughts were to develop an attraction by uncovering the ruins. He promoted excavation both for the visual effect and to obtain artifacts that could be displayed. Opening ruins also provided a means to learn more about the ancient people, and, therefore, furnish material for the interpretive story. In 1918, by the beginning of his second custodianship, experience had taught Pinkley additional means to promote the monument. Publicity was one key to attract visitation. Toward that end, Pinkley obtained an agreement with the state news agency to circulate stories about the monument. He spoke to social and business groups in the state and contacted the Southern Pacific Railroad to get that company to promote tourism to the monument. He worked with local women's clubs to obtain their help in publicizing the ruins. At his request, the National Park Service supplied copies of a general information pamphlet. He hoped to develop a mailing list from the names and addresses that people entered in his registration book, but lack of funds prevented Pinkley from producing either his mailing list or obtaining the assistance of Byron Cummings of the University of Arizona Anthropology Department and T. E. Farrish, the state historian, to produce additional pamphlets. In effect Pinkley took the same actions that Mather and Albright used to promote the national parks.

A. The Evolution of the National Park Service Interpretive Story

Interpretation or the presentation of a factual story provided one means to educate the public. Pinkley sought to greet all visitors and provide them with as much interesting information about the ruins and the inhabitants as possible. Over the years, tours, whether conducted by Pinkley or monument rangers, usually lasted from forty-five minutes to an hour. Occasionally, in the earlier days when visitation was less, Pinkley would linger for as long as two hours to answer the questions of interested parties. The principal theme Pinkley and others presented to visitors over the years dwelled on the Hohokam occupation at Casa Grande.

Prior to the establishment of the Casa Grande Reservation in 1892, pioneering anthropologists provided the first interpretation of the prehistoric era. Partly from the early anthropologists' ideas, and partly from excavations and his own thoughts, Frank Pinkley established an interpretive story that remained the basis for explaining the prehistoric peoples from 1918 to the early 1960s. At the monument the mediums used to tell this story have been ranger talks, guided tours, self-guiding trails, museum displays, pamphlets, and books.

The first interpretation of the prehistoric Hohokam culture to be based on more than speculation developed in the 1880s. At that time two newly created archeological research societies (Archaeological Institute of America and the Smithsonian-affiliated Bureau of American Ethnology which was known as the Bureau of Ethnology after 1894) studied the Casa Grande and incorporated it as part of a larger debate about the prehistory of the Southwest. Consequently, two different interpretations about the use of the Great House developed. Adolf Bandelier, who worked for the Archaeological Institute of America, at first believed that the Casa Grande served as living quarters, but by 1892 he changed his mind and wrote that it was a fort. This view was later adopted by Frank Pinkley for his interpretation program even though his early explanations were influenced by J. Walter Fewkes of the Bureau of Ethnology who excavated at the Casa Grande reservation during the winters of 1906-07 and 1907-08. The Bureau of American Ethnology's position on Casa Grande came from F. H. Cushing who had led the Hemenway Expedition in the late 1880s. Cushing believed that the prehistoric culture that had occupied the Gila and Salt River valleys was a society composed of many classes and led by priests. He decided that the Great House had been occupied by the priest class and served as a temple. The lower rooms in the Casa Grande had been used to store tithed grain. After his excavations in 1906-07 Fewkes modified that viewpoint somewhat. At that time he wrote that the Gila Valley and its tributaries had been inhabited by an agricultural people who were ruled by a chief. These people built great houses which served as places of refuge, ceremony, and trade. In time, hostile migrants came from the east for pillage and drove the agriculturalists from their villages. Some of the inhabitants moved south to Mexico, others went north to the Verde Valley and Tonto areas, while a few people remained in the Gila River region and became the ancestors of the present day Pima and Papago. [1]

Pinkley accepted Fewkes' interpretation at first and placed an extract of it in a 1909 General Land Office publication. He noted that the structures with massive walls had served as temples, granaries for corn storage, and forts for protection against foes. The common people, he wrote, lived in rectangular-shaped dwellings whose upright log walls were covered with mud or clay. [2]

By 1918, when Pinkley returned to Casa Grande for his second custodianship, he had developed the basic National Park Service interpretive theme which would be presented to the monument visitors until 1964. Pinkley reasoned that the prehistoric people did not come from a long migration to the area. They could have come from as little as 150 miles away. He adopted the traditional hunter! gatherer story to explain the prehistoric people's early appearance in the area. In developing that story, Pinkley told visitors that these people did not settle along the Gila River at first, but sought a home in the mountainous areas of central Arizona. Since these higher elevations prevented agriculture, the people lived as hunters who followed game from one mountain range to another. Pinkley reasoned that hunting and gathering did not provide adequate food, so gradually these people left the nomadic life and settled in the flat valleys where they experimented with agriculture and irrigation. Pinkley saw an ever upward progression of their culture because the development of an agricultural society led these prehistoric people to produce enough food and to live in better houses. [3]

Pinkley wrote that the first valley settlements were close to the Gila River since the early irrigation ditches did not extend far. Archeological evidence showed Pinkley that early houses consisted of crude reed-and-brush-covered structures and also demonstrated that these people developed more complicated dwellings. The change in house design led Pinkley to decide that someone of the prehistoric group eventually put mud on the brush to keep out the wind and this experiment resulted in the discovery that mud made the house cooker in the summer and warmer in the winter. Consequently, Pinkley thought, the people tried to make the mud walls thicker, but mud applied to brush could not be made more than three to four inches wide without collapsing. Archeological evidence revealed to Pinkley that, about AD 700, a new development in wall construction occurred when three-inch or more diameter timbers were used as core rods to make mud walls up to ten inches thick. This development, Pinkley thought, resulted from experiments. [4]

Pinkley told visitors that the prehistoric inhabitants of Casa Grande originally lived in peace, but, in time, other Indians moved into the mountainous areas and became a source of trouble for the agricultural people by raiding their crops in poor hunting years. Other than a preconceived picture of native populations, Pinkley had no evidence for raids. He merely used ideas developed by Bandelier and supposedly confirmed by Fewkes' excavations that this prehistoric society lived in a fort. No one ever thought to explain the need for walled villages in any other terms than for a defense system. The walled fortress idea led naturally into the next conclusion that people would also want to see the approach of an enemy. That idea, of course, led Fewkes to the watch tower conclusion which was an easy way to explain the pyramidal mounds topped with houses that he uncovered in Compound B. This was followed by the great house concept as the ultimate watchtower. Pinkley decided that, through experiments, the prehistoric people discovered that walls could be made taller without pole supports by making them thicker. Consequently, the National Park Service story stated that at first a great house was three stories tall, but soon other buildings had a fourth story to make it possible to see an enemy at a greater distance. The wall construction techniques for these taller structures came from observations that the walls were laid by hand in two-foot courses without forms. Since the ground floors of the four-story buildings were filled with dirt, Pinkley could think of no other explanation than it was necessary to absorb wall strain. Believing that no one would waste space, Pinkley decided that, in addition to functioning as watch towers, these great houses served as living quarters. He also thought of the buildings as a final line of defense. How else to explain the small doorways other than to force an enemy to come through the entrance one at a time in a stooped angle. Pinkley would explain to visitors that, in this defenseless position, it was easier for the defenders to hit an attacker over the head. To add to the defense story, Pinkley decided that a parapet on the roof allowed defenders to stand or kneel behind it. [5]

Pinkley concluded that, at their most prosperous period, the prehistoric people probably numbered between 8,000 and 15,000 in both the Gila and Salt River valleys. The trash remains and irrigation canals told Pinkley that these people farmed extensively and raised cotton and corn. Archeological excavations unearthed implements which provided display items. Fewkes, Pinkley, and others found that these city dwellers used stone, wood, and bone for tools and brought shells from the seashore for decorations and ceremonies. By making excavations of his own, Pinkley decided that the elliptically shaped depression between Compounds A and B was not a reservoir, as Fewkes thought, but an open air gathering place for ceremonies or games. Pinkley thought that it was used twice each year for ceremonies to pray for a good crop and to thank the gods for the harvest. [6]

Although Pinkley did not know when the Apache migrated to the southern Arizona area, he speculated that it was probably these people who joined the mountain inhabitants and gradually pushed the valley dwellers from their homes. The Apache, Pinkley thought, were not interested in agriculture and would have burned the villages. This view explained to him the reason for the burned rafters and roofing material found in excavated rooms. At a later date, Pinkley believed, the Pima and Papago came into the area, but they were not advanced enough to restore and use the villages. [7]

Pinkley added to his interpretation of the Casa Grande occupation after Harold Gladwin made several excavations in the monument during February and March 1927. Gladwin, an archeologist with the Southwest Museum in Los Angeles, cut through several rubbish mounds to examine the layers of trash placed there over time. In this manner he hoped to find the changes that had occurred in the prehistoric society. Gladwin could not trace the identity of these prehistoric people to any existing society. He was certain that the Pima culture had no similarity to the ancient Casa Grande occupants. Unable to provide an identity for this culture, Gladwin accepted the Pima name "Hohokam." Consequently, the term Hohokam came into common usage both in the interpretive program and among archeologists. [8]

Gladwin felt that too much emphasis had been placed on the use of compound walls and the Great House for defense. Since the Casa Grande museum building had been destroyed by a flood only two years before Gladwin arrived, he decided that the compound walls had served for flood protection. In addition, the Great House had been built for storage protection from floods which, he thought, explained the reason why the prehistoric people had filled the ground floor with earth. [9]

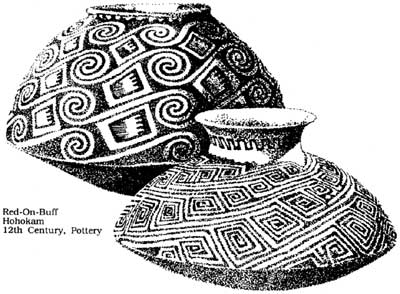

Pinkley did not accept Gladwin's flood idea. He continued to emphasize the defense interpretation. At the same time, Pinkley did adopt another of Gladwin's conclusions. After slicing through several rubbish mounds, Gladwin noted that the lower, thicker layers of trash contained pieces of traditional Hohokam pottery. He described this earthenware as red-on-buff. Previously, it had been called either "old red ware" or red-on-gray. The narrow top layer, however, included pieces of a different pottery. This polychrome pottery was similar to that manufactured by the Salado, a puebloan people who lived to the northeast of the Hohokam territory. As a result, Gladwin decided that, in the last period of Hohokam occupation, the Salado had migrated to the Gila Valley and lived peacefully with them. He believed that not only the change in pottery proved the theory, but the change in building style to multi-storied structures showed the pueblo influence. Additionally, Gladwin found a change in burial customs which only further confirmed his belief in a Salado migration. The traditional burial practice of the Hohokam had been cremation with the ashes placed in red or red-on-buff pottery. Gladwin, however, discovered skeletal remains which had not been cremated. These remains were only found with the Salado polychrome pottery. He concluded, therefore, that the Salado had influenced the Hohokam to change from cremation to inhumation. [10]

|

| Red-On-Buff Hohokam 12th Century, Pottery. |

Within a year after Pinkley's death in 1940, a slight interpretive change was made. Visitors were told that the Hohokam had migrated to southern Arizona from northern Mexico. Monument personnel stated that the greatest range of Hohokam culture came about AD 1000 when it extended from the Flagstaff area to the Mexican border and from New Mexico to present-day Gila Bend. Over the next several hundred years, their territory shrank and people settled in compact villages surrounded by high walls for protection from an enemy. Park Service speculation now made the foe a Yuman group from the lower Gila and Colorado rivers instead of the Apache and mountain people because it was now known that the Apache had arrived in southern Arizona at a later date. Rangers repeated Gladwin's idea that, about AD 1300, the Salado, who dwelled on the upper reaches of the Salt River, were pushed into the desert by drought. They migrated to the Hohokam settlements where, as Gladwin thought his excavations showed, they influenced that culture as seen by the construction of multi-story buildings, the manufacture of polychrome pottery, and a new burial practice. National Park Service archeologists accepted Gladwin's theory because it made a good story to explain the appearance of the great house style architecture. No one thought to carry through with Pinkley's earlier idea that architectural change had come about through experiment. Visitors learned that shortly after 1400 the union ended and both the Hohokam and Salado abandoned the Gila River villages. Since most events are usually said to result from complex causes, the National Park Service story included other incidents to explain the end of the prehistoric culture. No longer were people told that the Hohokam and Salado departed their homes only because of attacks from hostile neighbors. Rangers provided a series of other factors which included the possibility that the soil had become waterlogged through years of irrigation, that silt had filled canals, and that, in all likelihood, a drought had occurred. Unlike Pinkley's idea, at least in part, the Hohokam were thought to have remained in the area to become the ancestors of the Pima. [11]

Only one variation in this interpretive story occurred during the 1950s. In 1952 Albert Schroeder claimed that the people who migrated to live with the Hohokam were not Salado, but the Sinagua who had resided to the north in the present-day Flagstaff area. Consequently, neither the name Salado nor Sinagua was used in reference to these people. They were termed people of pueblo origin. [12]

The entire interpretive story changed in 1964. When Charlie Steen excavated a small, previously undisturbed area in Compound A in 1963, he found evidence that Casa Grande had always been occupied by only the Hohokam. Steen wrote that, prior to that time, he had firmly believed in the "Salado-in-the-desert" idea. From the time of Gladwin's excavations in 1927, Compound A was considered the product of Salado construction because of its architectural style and the time in which it was built (soon after 1300). Under that circumstance, Steen should have found mostly pieces of Salado polychrome pottery. Instead, the pot shards he located were either Hohokam Gila Plain or red-on-buff. The few pieces of polychrome that he found had to be obtained from trade. Subsequent excavation at Hohokam sites by such archeologists as David Doyel of the Arizona State Museum have shown that there was no migration of Salado or any other people to the Hohokam villages. Gladwin had come to the wrong conclusion. The development of multi-story caliche buildings resulted from a transition in Hohokam building techniques. As a result of this new evidence, the interpretation of the Hohokam civilization changed to that presented in the first chapter of this study. [13]

Another subject interpreted at Casa Grande involved the use of the Great House for astronomical purposes. Sometime during his first custodianship, Frank Pinkley noticed that there was a system of holes in the east wall of the Great House through which the rising sun aligned each year on the mornings of March 7 and October 7. By 1918, without any study or investigation, he explained to visitors that these holes were used twice each year as a solar calendar to date ceremonies. In 1920 Pinkley broadened his astronomical interpretation after he discovered holes in the Great House's north wall. He invented an elaborate initiation ceremony story, which involved "calling down the stars," to explain these holes. Pinkley told visitors that, to impress the tribal youth during initiation, priests would get them to peer through these northward facing holes at night. On the opposite side of the wall a priest would hold a bowl of water that reflected star light. In the dark that reflected light would appear as if the priest had called down the stars to earth. [14]

Although it was later discovered that the north wall "astronomical holes" had been drilled during the 1891 preservation work, studies of the east wall holes, beginning in 1969, supported their use for solar observations. Prior to that date Southwestern Monument and Casa Grande employees merely observed the sun's alignment in the spring and fall and wrote articles to publicize this solar phenomenon. No comparative studies were made with either contemporary societies or historic groups to learn of their astronomical practices. It was only assumed that the Great House holes were used as a solar calendar. Wishing to have the holes studied, the Southwestern Archeological Center contracted with John Molloy in 1969 to investigate the Great House holes. He identified fourteen holes that he felt were used to make lunar and solar observations. This development of astronomy at Casa Grande, Molloy thought, had come from Mesoamerican influence. In 1971 his report was accepted with reservations because he had merely described the holes and their lunar and solar orientation. Molloy did not list any importance for the holes or state any reason for their astronomical use. Another contract was issued to John Evans in 1978 for further study of the holes. He found that two holes on the east wall had a solar alignment with the spring and fall equinoxes while one hole on the west wall aligned with the setting sun at the summer solstice. Soon after Evans began his investigation, Renee Opperman conducted her own observations. She made a comparative study of rituals in relation to astronomical developments in both prehistoric and historic Native American cultures. On the basis of similar astronomical uses in both North and Mesoamerica, Opperman concluded that, because of the Great House orientation along with the equinox and solstice holes in its east and west walls, the inhabitants of Casa Grande depended upon the heavens "as a source of life or of signs that aided in sustaining life." [15]

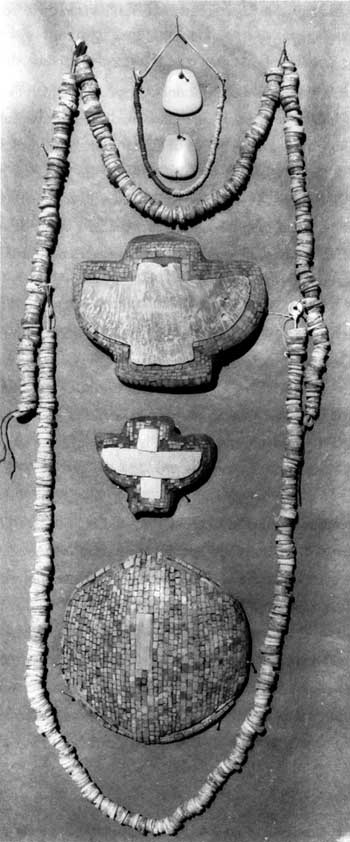

B. Publicity, Visitation, and the Interpretive Medium

Between 1889 and 1901, the first two Casa Grande custodians made no effort to attract visitors or to interpret the site. Making only infrequent inspections, these men considered ruins protection to be their only duty. The situation changed with the appointment of Frank Pinkley as custodian in 1901. Because he was stationed on site, he had the opportunity to do more than merely protect the ruins. Pinkley decided that attracting visitors and providing them with information ranked on an equal basis with protection and development. From the time of his first appointment at Casa Grande, he made an effort to treat visitors as if they were guests. No one viewed the ruins in Compound A and ultimately the museum without a personal guided tour. With experience, Pinkley developed several methods to attract and educate the public about the inhabitants of the Gila Valley and their environment.

From the first, Pinkley desired to learn more about the reservation's prehistoric inhabitants in order to inform visitors about these people. Soon after his arrival at Casa Grande, his investigations produced some artifacts. He displayed these items on wooden shelves in the north room of the Great House. Pinkley, however, did not think these few remains of a past civilization were sufficient to interest or attract a larger number of visitors. What he really desired was to have a large-scale excavation. Opening the ancient mounds would publicize the ruins as nothing else could and bring ever increasing numbers of people to view them. It would only be so much the better "if weapons and utensils could be found" along with information on the origins and customs of the long departed people. [16]

It undoubtedly delighted Pinkley when he learned that $3,000 had been appropriated for the Bureau of Ethnology to conduct an archeological excavation at Casa Grande in fiscal year 1907. A like sum was added in the succeeding fiscal year. J. Walter Fewkes, the archeologist who supervised the excavations, opened 100 rooms of which most were in Compounds A and B. Since these rooms remained open for viewing. Fewkes with Pinkley's help turned Casa Grande into an exhibition ruin. This situation provided Pinkley with the opportunity to greatly expand his interpretive program. Now, not only could he lead groups of people through the rooms of Compound A and the Great House, he had other attractions to show them. For a self-guided tour, Pinkley constructed wooden steps in Compound B which permitted visitors to climb to the top of the pyramids and look into various rooms. He also built a bridge to connect the top of the west Compound B wall to a nearby refuse mound so that people could view ancient pits that had been used to mix the caliche building material. Pinkley placed information labels along the Compound B route and erected a large placard there which contained historical data. These measures worked for Pinkley, for, with each annual report, he commented on the ever increasing visitation. James Bates, Pinkley's successor, seemingly did not take as much interest in increasing visitation or interpretation. He may even have removed the steps and bridge that Pinkley had built at Compound B since they did not exist when Pinkley returned to Casa Grande in 1918. [17]

Pinkley's delight about the 1906-07 excavation turned to disappointment when Fewkes began to ship all of the artifacts that he had uncovered back to the Smithsonian. Pinkley felt that these articles of the ancient civilization should be left at the site of their excavation. To remove them to a faraway location robbed him of the opportunity to use them to attract visitors. After he protested their removal, some items were left for him to display. Pinkley had to be content, however, with building more shelves in the north room of the Great House to display the monument collection. In 1909, his request for a $2,000 appropriation to build a museum in which to exhibit the artifacts went unanswered. [18]

When Pinkley returned to Casa Grande in 1918, one of his main concerns was to promote the ruins to attract even greater visitation. To provide an attraction, he wrote that "new ground needs to be opened to stimulate interest and publicity." In addition he began to place articles in newspapers, give lectures to area social groups and schools, distribute copies of a general information pamphlet that the Park Service had sent to him, and advertise with the railroad for tourists. In July 1918 Pinkley made a tracing of Compound A drawn on a scale of 1/8-inch to one-foot. He hung a copy of it in the Great House and referred to it during talks to visitors. [19]

To stimulate interest in the monument, Pinkley began to make test excavations in the elliptical depression north of Compound A beginning in November 1918. Pinkley hoped to learn its use, although Fewkes had speculated that it was a reservoir. He reported this excavation work to Stephen Mather, the National Park Service director. Mather did not tell Pinkley, as the General Land Office Commissioner had done in 1902, that archeological explorations had to be done by trained archeologists. Consequently, Pinkley made or authorized excavations over the next fifteen years without permission from any higher authority. By 1918, however, Pinkley was no stranger to archeology. He had learned excavation techniques from Fewkes when he helped him with the 1906-07 and 1907-08 work. For that time, Pinkley probably excavated as carefully as anyone. George Boundey, his assistant in the 1920s, however, operated more as a treasure hunter than as an archeologist when he opened areas of the ruins. [20]

During December 1918 Pinkley continued his test excavations on the elliptical depression. His findings provided him with more interpretive information. Digging various random pits, he located a caliche floor a little more than two and one-half feet below ground level. The floor measured eighty-one feet, eight inches by forty-six feet, three inches. On the east and west sides it sloped upward toward the edge. There was no sloping wall at the north and south ends. Instead, he found a two-foot-wide path at each of those ends which he thought probably served as entrances. In the center, Pinkley located a hard green stone imbedded in the caliche floor. It measured about ten by fourteen inches. Out of curiosity, Pinkley tested another elliptical area at a ruin east of Casa Grande. Although it was similar to the depression on the monument, he found no stone in the center. Pinkley concluded that the area had served as a place for "ceremony, games or festivals." Consequently, he used that interpretation when explaining the site to visitors although he put the greatest emphasis on ceremony. [21]

In early 1919 Pinkley reported his intent for further excavations. He told Mather that he hoped to open a trash mound on a foot-by-foot basis to see if, in the various layers, there was a difference in materials, pottery design, or workmanship. Pinkley again told Mather that "I like to keep a little new work under way all the time, for I find that it doubles the interest of visitors to see something in the act of being opened." At the same time Pinkley wrote that he hoped to spend $300 in 1920 to make experiments with pits and trenches. The press of business, which often took him to other monuments at the request of the Washington office, and the doubling of visitation from 3,677 in 1919 to 7,720 in 1920, prevented him from making excavations for two years. [22]

In 1922 Pinkley finally received an appropriation to build a museum to house the artifacts and other interpretive materials. The adobe building that he constructed contained only one eighteen by-twenty-foot room for museum displays. It also served several other purposes including an administration office, a files and storage room, a library and map room, and a small restroom. When he returned to Casa Grande in 1918, Pinkley began to collect books on the prehistoric inhabitants of the area as well as on the history of Arizona. Any visitor who showed a great interest in Casa Grande would be allowed to use the museum library to further his knowledge. With the completion of the museum, Pinkley hoped to have any duplicate artifacts from the collection that Fewkes had sent to the Smithsonian returned to the monument. He did not succeed in his quest. He did, however, encourage local people to donate artifacts for display items. When a flood caused this 1922 museum building to collapse in 1925, Pinkley managed to rescue his artifacts and interpretive material. He again displayed them in the rebuilt structure which contained the same museum space as the previous building. [23]

Pinkley received what should have been good news in 1927, when he learned that the Arizona legislature had passed a law which required that fifty percent of all excavated artifacts had to be kept in the state. By this time, however, Pinkley did not mind having material removed to distant museums. He thought that such displays would serve as good publicity to attract people to see the artifact source at Casa Grande. Besides, Pinkley reasoned, he did not need case after case of duplicate items displayed in his museum. It was better to have a "working museum" with a compact collection that illustrated a cross section of life and the degree of culture. [24]

By December 1922 Pinkley returned to excavating at the monument. In addition to increasing his knowledge about the prehistoric inhabitants, he probably hoped to obtain more artifacts to put on display in his new museum. In February 1923 he completed the excavation of a room located about sixty feet northwest of the Great House. He found a fire pit, burned grass and reeds from the roof, wall plaster that had been decorated by using fingertips, several stone tools, and a small stone bowl. In addition Pinkley recovered almost a wheelbarrow full of pot fragments. After he had examined the room, it was backfilled to keep it from weathering. In May three burials were salvaged. [25]

In June 1923, Pinkley turned his attention to a one-acre area in which he had found artifacts in the past. Some twenty years previously, he had made a surface collection of about 200 arrowheads, several hundred beads, fragments of human bone, and pieces of shell bracelets that had been burned. At the time, he thought that a small battle had occurred there. In his 1923 investigations, Pinkley found that the debris went down two feet. As a result, he put fifty wheelbarrow loads of the dirt through a screen. From that, he obtained enough beads to make thirteen strings, each one foot long. The beads came in two sizes of fourteen to sixteen to an inch and thirty-seven to forty-five to an inch. [26]

Although Pinkley stated in his 1924 annual report that no excavation work had been done during that fiscal year, George Boundey, who was now employed at the monument, had opened some areas. While Pinkley was working at Tumacacori, Boundey did trenching work to test for subsurface walls and rooms. Even though he located some of these features in January and March 1924, he excavated no rooms. Consequently, he did not locate any artifacts that could be added to the museum collection. [27]

Boundey began to excavate in earnest in October 1924 and continued into 1926. Aided by John Huffman, a temporary employee, Boundey opened several trash mounds. Pinkley decided that these rubbish heaps were among some of the older ones because only red-on-gray (later called red-on-buff by Gladwin) pot shards were found. In December 1924, when stabilization work began on the ruins' walls and the surfacing of room floors, Boundey used this opportunity to further his search for artifacts. Before he surfaced a room floor, he would completely "tear up" the area and examine beneath it. Travel on Southwestern Monument business kept Pinkley from witnessing most of Boundey's excavation work, but he felt that his assistant carefully opened the floors. In the course of this activity, Boundey found a number of burials and many artifacts.

He discovered shell jewelry, rock tools, bone awls, numerous pieces of pottery, and a copper bell which dated from the "sixth century of the Maya era in Yucatan." On January 24, 1925, Boundey located his most impressive find under the floor of a Compound A room. It comprised a spectacular cache of turquoise mosaic work in the form of birds and a turtle (figure 26). To attract attention, Huffman wrote a magazine article describing the find. Pinkley would occasionally take that collection with him as a publicity promotional when he addressed groups such as the Phoenix Chamber of Commerce. [28]

Harold Gladwin of the Southwest Museum of Los Angeles surprised and pleased Pinkley when he applied for a 1927 permit to excavate trash mounds at Casa Grande. He proposed to examine the discarded pottery found in each layer of a mound because he believed that pottery stratification was the key to archeology. The only effort to examine the contents of such refuse piles had been conducted by Boundey in late 1924. At that time he reported finding red-on-gray pot shards. Gladwin's discovery of polychrome pottery led to an interpretive modification as previously recounted. [29]

|

| Figure 26: Turquoise Mosaics Found in 1925. Courtesy of the Western Archeological and Conservation Center. |

Two minor excavations were carried out in the early 1930s. In December 1929, the Van Bergen expedition from the Los Angeles Museum obtained a permit to excavate at Compound F. Arthur Woodward directed that work along with a project at the Grewe site one mile to the east of the monument. Only part of Compound F was opened and remained that way until it was backfilled in 1940. The Los Angeles Museum did not publish the results of the excavation. In a make-work project between December 11, 1933 and February 15, 1934, Russell Hastings of the Gila Pueblo in Globe, Arizona supervised Civil Works Administration men who excavated in the southeast corner of the monument. In two operations he tested four rubbish mounds and opened more than fourteen rooms. He exposed three types of dwellings and an unroofed kitchen or work area. Hastings considered part of the excavated area to date from AD 900 while the other was between AD 1250 and 1350. In the process he found one cremation pit and twenty-two cremation burials. Hastings ended the work because he decided it would not add any new knowledge. He had the site backfilled. Hastings' report was very general and confusing, for he never pinpointed the excavated area and he never discussed artifacts, only dwelling remains. [30]

Only three minor excavations have been done at the monument since 1934 along with a proposal for additional work. In December 1962, Superintendent Aubrey Houston proposed to dig a twelve-foot-deep hole in the center room of the Great House. Both Gordon Vivian and Charlie Steen opposed it on the basis that a hole that deep would be far below the foundation. The resulting refill could settle and cause the walls to shift. Any attempt to tamp the earth with a machine would cause too much vibration. In 1963 Charlie Steen did limited excavation in two areas of the southeast section of Compound A. The cultural material that he unearthed there prompted a great change in the interpretation presented to visitors. In 1973 Duane Spears of Arizona State University conducted tests in Compound B to determine the extent of original features remaining after the Fewkes excavation of 1907-08. He found that a number of these features remained and he recommended that they be covered with earth. In the final excavation, between May 30 and June 3, 1977, David Wilcox exposed four hearths and a burned floor area in Compound A. He also opened a pit house under the outer wall of Compound B. Wilcox's purpose in this exercise was to obtain samples for archeo-magnetic dating. He ultimately reported that this test on material from a hearth in the southeast corner of Compound A indicated a date of AD 1350 plus or minus 17. [31]

Pinkley sought to publicize the monument in many ways. One of the most unusual was an annual pageant. Because it proved to be so destructive to the ruins, Pinkley undoubtedly came to regret the day that he consented to that spectacle. The subject of a pageant first surfaced in May 1922 when the Women's Clubs of the towns of Florence and Casa Grande met at the monument to discuss ways to give the ruins more publicity. They decided that one means to get people to come to the monument from long distances would be to hold a pageant. [32]

The idea grew to the point that a number of prominent Arizonans established an Arizona Pageantry Association to promote education. James McClintock served as the president of the group. By November 1925 the pageantry association pledged to raise $10,000 for the Casa Grande extravaganza. Garnet Holme, the National Park Service pageant director, was chosen to supervise the play. He came to the monument in November 1925 to "gather impressions" for the pageant which was scheduled to be held in November 1926. [33]

Compound B was chosen as the site for the pageant. A multi-story wooden building painted to resemble adobe was constructed on the compound. Only limited seating was provided on a mound to the west of Compound B. Most people attending the play sat on the ground. A cast of 300 persons was selected and a three-day production was chosen for November 5-7, 1926. In clouds of dust a total of 13,000 people arrived in thousands of cars. A great deal of natural vegetation was destroyed as people randomly parked their vehicles near Compound C. The pageant consisted of four dramas which had little connection to either the prehistory or history of the monument. Pinkley must have wanted to go into hiding by the end of the affair. The first episode told the "tragic" story of prehistoric Pueblo Indians who had been driven from their homes. This was followed by a Pima production of songs, dances, and rituals that ended when Coronado arrived. Angered at not finding gold, Coronado destroyed the Pima village. In the third part Padre Kino appeared on stage as the first European visitor to the abandoned ruins. He came to bring God and learning to the "superstitious" and "illiterate" savages. Finally, the actors performed "beautiful Spanish love songs and fandangos" to show the "gaiety and revelry" of Spanish life in the Tucson of old. In the midst of the celebration "kong-bearded, dour-faced men and worn, colorless women" moved onto the stage. These Mormon missionaries from Salt Lake City halted the festivities. In the finale, the cast members from all four dramas gathered to sing "Oh God, Our Help in Ages Past." [34]

The pageant proved so successful that the Arizona Pageantry Association voted to continue with the performance the following year. Pinkley made greater preparations for the second pageant which was held on November 4-6, 1927. He had the state police supervise parking. The compound area was treated to keep down the dust. A children's nursery was added. The 1927 pageant attracted 10,000 people. No pageant was held the following year as it was postponed to March 8-10, 1929. Attendance dropped to 7,000. When only 5,000 came to the fourth event, which was held March 28-30, 1930, the Association decided not to sponsor further pageants. Although the stage and multi-story building were dismantled, the lumber was left in a pile next to the compound. It was not removed until December 1937 when the CCC cleaned the area. [35]

By the late 1920s, little publicity was necessary as at times visitors almost overwhelmed the monument staff. Prosperity and the increased use of automobiles brought a drastic rise in visitation during the 1920s. Between 1926 and 1927 the number of people who stopped at the monument rose from 16,542 to 28,274. Fortunately for Pinkley, he was able to increase the monument staff from two to three in March 1927. By the end of 1927 he hired a fourth person, but he had a hard time keeping the clerk-stenographer/ranger position filled. The low pay made it hard to attract a married man. Consequently, that position would be vacant for long periods. On busy days, visitors had to wait to enter the eighteen-by-twenty-foot museum. In 1929 visitation reached a pre-depression high of 37,244 individuals. At times during that winter, the crowds became too large to handle. Pinkley had set a maximum hourly capacity of seventy-five persons. The three staff members could take only three groups of twenty-five each through the museum and on a guided tour each hour. Some hours, however, more than 130 people would arrive, making it necessary to increase the tour group sizes to more than forty persons. Under that circumstance, visitors' appreciation and support for the monument as well as their learning experience greatly diminished. [36]

To provide a more pleasant atmosphere and relieve the museum overcrowding, Pinkley received an appropriation to construct a new administration/museum building in fiscal year 1932. The building, which included three offices, three exhibit rooms, and a preparation room, was completed on January 5, 1932. The largest of the three museum rooms contained displays interpreting the Hohokam culture. The second room held a poorly organized artifact collection in homemade cases and the third room contained an exhibit on the modern Pima, Maricopa, and Apache tribes. There was no space devoted to natural history. [37]

Frank Pinkley recognized that a new museum alone would not sustain public support. Well presented museum material went a long way toward selling the public on the monument as well as providing a better educational opportunity. Consequently, in 1931, he hired Robert "Bob" Rose, a park naturalist and geographer with museum experience, as his second employee in the Southwestern Monuments office. As part of his duties, Rose developed museum and other interpretive exhibits. One of his first jobs was to improve the Casa Grande museum displays. He rearranged the Hohokam culture room with eight new homemade exhibit cases. Frames were made for charts, maps, and photos which included the "Culture Map of Arizona," "Genealogical Tree of Southwestern Pottery," "Summary of Arizona Archaeology," a map of the "Prehistoric Canals in the Salt River Valley," and a photo of the Cretan Copper Coin with "Maze." Modem Indian baskets, including a partly completed Pima basket, were placed in the room that contained the exhibits on the present-day area Indians. Although Rose felt that more museum space needed to be devoted to natural history, about all that was added was a petrified wood display. To accompany the museum material, Rose planned to reconstruct two types of the earlier prehistoric Hohokam houses to show the architecture styles that preceded the Great House. He wanted to locate these two dwellings on such a site as to make it possible to include them in the ruins and museum guided tour. These prehistoric house types were never constructed. [38]

By December 1932, Rose complained that the museum had become overcrowded with the acquisition of more Hohokam material. Some of that material was stored in the preparation room where interested visitors were invited to see it, but this did not solve the space problem. As Rose saw it, only the construction of the proposed museum addition could answer the need for more room. Since funds to expand the museum were not forthcoming, the Casa Grande and Southwestern Monuments staffs had to make do with the existing space. In 1934 some new display cases were built and two models of Hohokam cremation burial customs introduced. In the following year, three more exhibit cases were installed, a tree ring chart was added, and a comparative pottery collection was displayed. By 1937 the area devoted to the museum suffered from the need to house a growing Southwestern Monuments' staff. As a result, the museum area was reduced to two rooms with hastily arranged displays in new exhibit cases. Space was no longer available to present graphic and pictorial material. Somehow, a display case showing the Hohokam irrigation system in the Gila and Salt River valleys was accommodated in the cramped museum in 1940. An exhibit on local reptiles was added in 1942. [39]

An improvement in museum space resulted with the departure of the Southwestern Monuments staff for Santa Fe in October 1942. As soon as it had left, Custodian Bicknell and Charlie Steen rearranged the museum and office space. By early 1943, they had changed the main museum exhibit room into the lobby. Some display cases were left there while others were moved into the three vacated offices located to the west of the lobby. This increased space permitted the installation of ten additional exhibits. The former Southwestern Monuments' clerical office housed archeological exhibits. Pima and Papago materials were placed in the former assistant superintendent's space, and Pima, Papago, Apache, and natural history items were shown in the office previously occupied by the Southwestern Monuments superintendent. [40]

The 1943 museum arrangement with its "temporary" exhibits remained unchanged until 1953. At that time archeologist Donald Jewell reduced the museum space to the three former Southwestern Monument office areas. In these rooms, he arranged eight main exhibit cases and several other, small homemade ones. Jewell removed all of the natural history displays and placed archeological material in one room while the two other rooms contained ethnological exhibits. He used the basic cultural theme, which had been interpreted at the monument since 1918, except that he dropped the term Salado and substituted Pueblo in its place to identify those Indians thought to have migrated into the Hohokam territory. [41]

In 1955, Albert Schroeder wrote a museum prospectus which included a proposed museum addition. He called for three-dimensional exhibits for greater visual interpretation. In addition to the prehistoric and historic themes, Schroeder advocated the need to interpret the Gila Basin geology as well as have floral and faunal displays which explained the ardent peoples' environment. As part of an expanded museum plan, Schroeder called for an excavated pit house site. He revised the prospectus in 1956 by deleting the exhibits planned for the projected museum addition. This section was removed to make the prospectus conform with the National Park Service Director's decision to omit the museum enlargement from the Casa Grande MISSION 66 program. [42]

Despite the earlier judgment not to include a museum addition in the MISSION 66 program, an enlargement did take place to that structure in 1964. In March of that year, a National Park Service Western Museum Laboratory planning team traveled to Casa Grande to begin preliminary work on new exhibits for the expanded museum. Regional Archeologist Charlie Steen told the team not to include any reference to a Salado or Pueblo migration to the Gila River Valley because recent evidence showed that no migration occurred. Both cultural and natural exhibits were installed in the museum in 1966. Few changes have been made in them to the present. Native vegetation was planted and labeled in the open courtyard. [43]

Although visitation during the depression years of the 1930s did not decrease much, the Casa Grande staff dropped to three at the beginning of that decade. With the establishment of a CCC spike camp at the monument in 1937, three to four of these young men were used to guide visitors through the museum and Compound A. At the same time, the Casa Grande personnel decreased once more to a custodian and a ranger. To relieve the pressure caused by increasing visitation, a self-guiding desert trail was established in March 1938. It was the first real effort to interpret natural history. This nature trail led a visitor on a twenty-minute circular walk by way of the ball court and Compound B. By matching the descriptions in a pamphlet to numbered posts, an individual could obtain information about the monument's vegetation, birds, animals, and archeology. This self-guiding trail served visitors until about the end of 1945. [44]

Visitation again dropped during the Second World War as gasoline and tire rationing prevented extended travel. On several occasions, Japanese-American students from the "Relocation Center" at nearby Rivers, Arizona were brought to the monument. At the same time, guards from the German prisoner-of-war camp at Florence often visited Casa Grande as well. Visitors during these years were met by the first female rangers to serve at the monument. Sallie Brewer [Van Valkenburgh] was the first to report on February 16, 1943. She served until July 1944. Just shortly before she departed, Jessica Shearwood arrived and stayed until May 31, 1945. Polly Tovrea transferred from the Weather Bureau to replace Shearwood. She resigned on December 29, 1945, to join her husband who had returned from the war. [45]

Following the Second World War, a force of only three permanent personnel and one seasonal ranger served at Casa Grande to meet the onrush of visitors. Between 1946 and 1956 the number of people coming to the monument almost doubled from 27,994 to 52,400, and still the same number of monument employees tried to cope with that number of people and give guided tours through Compound A. By June 1945, Spanish-speaking tourists received greater recognition when the first Spanish language leaflet came into use. [46]

In the mid-1950s Superintendent Bicknell requested another staff person for interpretation. He noted that one more employee would not only be of aid during the busy season, but could provide relief during the summer when frequently only one person would be on duty for four days per week. That one person could not give tours and also answer questions in the visitor center. Above all, however, one more staff member was essential in the winter season. During the busy winter times people had to wait as long as thirty minutes for a guided tour. To provide an attraction for those who waited, Bicknell proposed to reopen Compound B and the ball court for self-guided tours with exhibits-in-place provided that these sites could be adequately stabilized. No means was found, of course, to stabilize the ruins. In 1957 Bicknell got two more employees, but neither of them filled the needed interpretive position. In January a maintenance man was added to the staff. He did no interpretation, but he did free interpretive personnel from janitorial duty. Then in the fall of that year, Bicknell got an administrative assistant. This person relieved the interpretive staff from paperwork and occasionally had ticket sales duty. [47]

By 1961 the crowding had become very serious. The staff could no longer handle the crush of visitors that appeared on many winter days. Many people would not wait for a half hour or more to join a guided tour. Since the museum displays were not lengthy or interesting enough to hold a visitor's attention for any period of time, Superintendent Houston requested new exhibits. He also placed a ranger in Compound A as an attendant to serve those visitors who could not wait for the next tour. The latter solution proved to be an unsatisfactory method to meet the public. Visitors who came to the compound at a time when the ranger attendant was busy with other people tended to wander unsupervised. [48]

In 1963, the year that visitation passed the 100,000 mark, the museum expansion was approved. By that time, the monument had two additional employees — a supervisory ranger and a part-time laborer. Even then the number of visitors permitted only thirty-minute tours in the winter. In 1966 visitors had the choice of a self-guided tour through Compound A or paying the usual 25 cent fee to be escorted by a ranger. Visitors were still allowed into the Great House only on guided tours. [49]

The routine of the mid-1960s continued into the 1990s with the interpretive program still prominently featured as an attraction. The enlarged visitor center displays have undergone few changes in that time. Work, however, has begun on new exhibits to mark the hundredth anniversary. In the 1970s the staff increased to fourteen with half of these individuals serving as seasonal rangers. Between November 20 and April 30, three monument employees conducted hourly guided tours, while two staff members performed the same task the remainder of the year. In July 1973 tours no longer included the Great House interior. During the 1980s the number of seasonal rangers was reduced from seven to five. By 1990 the monument had only eight employees of which two were seasonal. Consequently, Superintendent Spencer developed a volunteer program. By 1990 fifteen volunteers relieved the monument's workload. Guided tours, during the heat of the year, have been reduced to accommodate only larger groups. The area open to the public has expanded to include viewing of the ball court from a raised platform. No longer are visitors charged 25 cents for a guided tour; instead, by the mid-1980s, they began to pay an entrance fee of $1.00 per person with a maximum of $3.00 per car. [50]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

cagr/adhi/chap6.htm

Last Updated: 22-Jan-2002