|

Casa Grande Ruins National Monument Arizona |

|

NPS photo | |

After a long battle with the desert, this ancient building still commands respect. Four stories high and 60 feet long, it is the largest known structure from Hohokam times. Early Spanish explorers called it Casa Grande ("Great House"), and to them it was a mystery. Its walls face the four cardinal points of the compass. A circular hole in the upper west wall aligns with the setting Sun at the summer solstice. Other openings align with the Sun and moon at specific times. Perhaps the Great House's builders, knowing well the ways of the land, would gather inside to ponder the heavens. Knowing the changing positions of the celestial objects also meant knowing times for planting, harvest, and celebration.

Who were these people who watched the sky so purposefully? Archeologist Emil Haury studied the Hohokam, calling them the "First Masters of the American Desert." Their origins lay with the Archaic hunter-gatherers who lived in Arizona for several thousand years, but Hohokam drew also from Mesoamerican civilization. By 300 CE (Common Era) a distinct Hohokam culture was in place along the Gila and Salt rivers and their tributaries. Like other southwestern farming people, they lived in permanent settlements, made pottery, and traded. The Hohokam diverted water from the rivers through vast systems of irrigation canals. Villages on the main canals formed irrigation communities that regulated the system. In areas with no perennial streams, they tapped groundwater or diverted storm runoff to dryland fields.

The people cooperated in trade too. Villages sat along natural routes between today's California, the Great Plains, Colorado Plateau, and northern Mexico. The Hohokam traded mostly pottery and jewelry for a variety of items. Gulf of California shells were so common they may have served as a medium of exchange, like coins. Macaws, mirrors, and copper bells show links to tropical Mexico. So do the shallow, oval pits found in major villages—maybe areas for ball games like the Aztecs played, or simply gathering places. Similar ballcourts as far north as Wupatki, a prehistoric site near Flagstaff, show the extent of Hohokam influence.

Declining popularity of ballcourts in the 1100s marks a gradual change in the Hohokam world. As the Classic period began, around 1150, people left outlying settlements to concentrate in large riverine villages like Casa Grande. Open arrangements of pithouses surrounding central plazas gave way to walled compounds. Besides houses the compounds sometimes contained solid, flat-topped earthen structures called platform mounds. The mysterious Great House was completed about 1350, in the late Classic period. This and other Great Houses, sited in villages at the ends of major canals, likely played a major role in the organization of the irrigation communities.

The Classic period lasted until the 1400s, when the Hohokam culture ebbed throughout the region. By the time Father Eusebio Kino and his party of missionaries arrived in 1694, they found only an empty shell of the once-flourishing village. Pima Indians, who lived nearby, said that their ancestors were "ho-ho-KAHM," meaning "all-gone" or "all used up." European-Americans began visiting the area in the late 1800s, and souvenir hunting threatened to destroy the site. The scientific community pressed for its legal protection, and in 1892 the Casa Grande became the nation's first archeological reserve. To this day the Great House keeps within its walls the secrets of an ancient people.

Builders found construction material in subsoil underfoot: caliche (cuh-LEE-chee), a concrete-like mix of sand, clay, and calcium carbonate (limestone). It took 3,000 tons to build the Great House. Caliche mud was piled in successive courses to form walls four feet thick at the base, tapering toward the top. Hundreds of juniper, pine, and fir trees were carried or floated 60 miles down the Gila River to the village. Anchored in the walls, the timbers formed ceiling or floor supports.

Saguaro ribs were laid perpendicular across the beams, covered with reeds, and then topped with a final caliche mud layer. The best efforts of its builders could not protect the house after it fell into disuse.

Despite centuries of weathering and of neglect, today the Great House stands as the most prominent example of Hohokam technology and social organization.

Casa Grande Ruins

The village comes to life before sunup. The first day of summer is a time of constant activity despite intense heat. Men depart the compound, carrying traps, bows, and arrows. This is the best hunting time, before animals seek shelter from the sun. Large animals are elusive; to hunt mule deer, pronghorn (antelope), or bighorn sheep means a long hike into the hills. Today promises to be too hot for such a trek. Besides, rabbits and pack rats are plentiful in the area and provide a tasty meal.

Saguaro fruits are ready for harvest. From a distance, the tall cacti appear to be in bloom. This is actually the ripe fruit splitting open to reveal bright red pulp. The people work quickly to collect the fruit before it is eaten by desert creatures who prize it equally. Gatherers maneuver long poles to knock the fruit from the tips of the cactus arms. It is hard to resist eating some of the fruit right away, but the people remember that other villagers have waited all year for the harvest. Pulp is eaten fresh or sun-dried. Juice is cooked down to syrup or set aside to ferment. Besides ceremonial wine, the fermented juice is used to make jewelry. Artisans paint designs on shells with resin. The shells are submerged in the saguaro juice, whose acid eats away the unprotected parts of the shell. When the resin is removed, the design remains raised above the surface.

Villagers take pride in their shell jewelry, ornaments, mosaics, woven cotton textiles, and pottery, which are popular not only with their neighbors but also with people known only through trade. As they work shaded beneath the ramadas, open-sided shelters, the artisans exchange stories of these faraway peoples and pass around tangible evidence of their existence. A black-and-white ceramic bowl from the north is serviceable, they note, but not as pleasing to the eye as their own designs. Far more enticing are the items from down south: copper bells and vivid red, blue, and green feathers from exotic birds.

A messenger arrives with news of an emergency at the canal. The men drop their work and head for the fields. They wind through waist-high cornstalks to where the main canal branches off into fields. One of the gates that regulates flow has been damaged and must be repaired before crops are inundated. A party returns with reeds from along the canal, which are quickly woven into a strong mat. The mat is reattached to the gate, and the gate is replaced. There is a collective sense of relief. This time they were able to make the repair themselves. At other times, particularly after heavy flooding, they must summon neighbors to work with them for days to clear gates, dredge channels, and reline canal beds with clay to prevent seepage.

Water from the Gila River. Food from the desert floor and hillsides. Building material from Earth itself. The natural world is the source of things that sustain life and deserve respect and gratitude. The people observe Earth and heavens carefully to know when to take the gifts nature offers and when to give thanks. That is why the people gather this evening in the Great House. Through a small, round hole facing west, people inside can briefly see the setting Sun directly ahead on the horizon. This means today is the longest day of the year, a comforting sign that the cycle of seasons continues.

A Bountiful Harvest from the Desert

Hot and dry, with few all-year water sources and little rainfall, the Sonoran Desert does not seem like a place to find the essentials for human survival. Yet for over 1,000 years the Hohokam managed to support a sizeable population on things grown, hunted, or gathered here.

Rivers are the lifelines—the Salt and Gila that originate in the east and meet west of present-day Phoenix. The Hohokam tapped the rivers with irrigation canals, diverted high water to the floodplains' rich soil, or captured rainwater.

Their crops withstood desert conditions. The staple, corn, matured fast enough to minimize exposure to the elements and produce two crops per year. They planted beans, squash, tobacco, cotton, and agave, too. Several wild plants, like amaranth, were encouraged in fields.

Known for farming, the people drew major sustenance from the wild, too, and did not have to search far; the desert was alive with useful plants and animals. Paloverde, mesquite, and ironwood trees provided wood, fruit, buds, and seeds. The open desert and foothills had ocotillo, creosote, bursage, and saltbush. It had edible cacti—saguaro, cholla, hedgehog, and prickly pear. Hunters snared rabbits and other small wildlife. Mule deer and bighorn sheep foraged hillsides.

Rivers supplied fish, waterfowl, and turtles and nourished lush vegetation nearby: mesquite, cottonwood, willow, reeds, and grasses. Some important domesticated and wild foods:

Mesquite pods, a staple food, were eaten whole or dried and pounded into meal. Many varieties of beans were eaten fresh or dried for storage.

Squash could be eaten fresh or boiled; hollow gourds made containers and rattles. Prickly pear fruit was eaten fresh or dried; the succulent pads (with the spines removed) were also edible. Corn was eaten raw, roasted, and parched, or dried and ground Into flour. Fish and Other animals were important protein sources.

Saguaro fruits ripened in early summer. The bright red pulp could be eaten fresh, dried, or used for making a ceremonial wine.

Red-on-buff bowls represent the most distinctive style of Hohokam pottery.

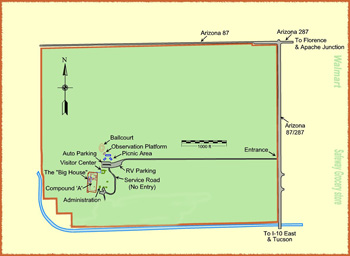

(click for larger map) |

Planning Your Visit

Casa Grande Ruins National Monument preserves remains of an ancient Hohokam farming village as well as the enigmatic Great House.

Location The park is in Coolidge, Ariz., an hour southeast of Phoenix. From I-10 take Coolidge exits and follow the signs to the park entrance off Ariz. 87/287.

Climate Summer temperatures in this desert country exceed 100°F, with thunderstorms in July and August. Winters are milder—60° to 80°—with longer periods of rain that can create brilliant desert wildflower tapestries in early spring.

Activities The park is open daily except for Thanksgiving and December 25. Contact the park (phone or website) for hours of operation. There is an admission fee. Inside the visitor center are exhibits of village life in Hohokam times. Outside, trails lead through ruins of what was once the largest compound in the prehistoric village. Signs enable you to tour the park on your own. More areas are visible from the observation deck in the picnic area.

Facilities There are restrooms, drinking fountains, and picnic tables in the park. Food service, stores, public phones, and fuel are available nearby in Coolidge.

For your safety and the park's protection Take precautions against summer heat and sudden rain or dust storms. • Pets must be leashed at all times in the park. Do not leave your animals unattended. • Do not feed wild animals or pick any wild plants. Watch for poisonous reptiles. • All ruins. artifacts, and natural features are protected by law and must be left undisturbed.

Source: NPS Brochure (2009)

Documents

Arizona Explorer Junior Ranger (Date Unknown)

Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, Arizona: A Centennial History of the First Prehistoric Reserve, 1892-1992 — Administrative History (HTML edition) (A. Berle Clemensen, March 1992)

Casa Grande: The Greatest Valley Pueblo of Arizona (HTML edition) (Edna Townsley Pinkley, 1926)

Colored Washes and Cultural Meaning at the Montezuma Castle Cliff Dwelling and Casa Grande Great House (Matthew C. Guebard, Angelyn Bass and Douglas Porter, extract from Journal of Arizona Archaeology, Vol. 5 No. 2, 2016; ©Arizona Archaeological Council)

Excavations at Casa Grande, Arizona (February 12-May 1, 1927) Southwest Museum Papers No. 2 (Harold S. Gladwin, September 1928)

Foundation Document, Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, Arizona (March 2017)

Foundation Document Overview, Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, Arizona (January 2017)

Geologic Resource Evaluation Report, Casa Grande Ruins National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/GRD/NRR-2018/1785 (Katie KellerLynn, October 2018)

Junior Arizona Archeologist (2016)

Long-Range Interpretive Plan, Casa Grande Ruins National Monument (January 2011)

Mission 66 for Casa Grande National Monument (c1956)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Casa Grande Ruins National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SODN/NRR-2019/1979 (Lisa Baril, Kimberly Struthers and Mark Brunson, August 2019)

Plants of Casa Grande Ruins National Monument NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SODN/NRR-2012/534 (Steve Buckley, ed., June 2012)

Status and Trends of Terrestrial Vegetation and Soils at Casa Grande Ruins National Monument, 2008-2016 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SODN/NRR-2018/1800 (J.A. Hubbard, Cheryl McIntyre and Sarah E. Studd, November 2018)

Status of Climate and Water Resources at Casa Grande Ruins National Monument: Water Year 2016 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SODN/NRR-2018/1629 (Colleen Filippone and Kara Raymond, May 2018)

Status of Climate and Water Resources at Casa Grande Ruins National Monument: Water Year 2017 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SODN/NRR-2018/1691 (Kara Raymond and Colleen Filippone, August 2018)

The Guide to Southwestern National Monuments Southwestern Monuments Association Popular Series. No. 1 (©Southwestern Monuments Association, December 1938)

The Casa Grande National Monument in Arizona (HTML edition) (Frank Pinkley and Edna Townsley Pinkley, March 21, 1931)

The History of Casa Grande Ruins National Monument (Sallie Van Valkenburgh, February 1962, reprinted May 1971)

Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Casa Grande Ruins National Monument USGS Open-File Report 2005-1185 (Brian F. Powell, Eric W. Albrecht, Cecilia A. Schmidt, William L. Halvorson, Pamela Anning and Kathleen Docherty, 2006)

cagr/index.htm

Last Updated: 21-Apr-2025