|

CASA GRANDE

Casa Grande: The Greatest Valley Pueblo of Arizona |

THE CASA GRANDE RUINS

ONE of the most interesting of our National Monuments from an historical standpoint is the Casa Grande Ruins which is situated in south central Arizona about midway between Phoenix and Tucson, and thirteen miles from Florence, Arizona, which is on the Bankhead Highway. From Florence the Casa Grande may be reached over a good dirt highway which passes thru a more or less cultivated district. This highway continues to Casa Grande station, on the main line of the Southern Pacific Railroad. The distance from Casa Grande Station to the ruins is twenty-two miles. There is still another approach, direct from Phoenix, Arizona, thru Sacaton. the agency village for the Pima Indians. From Sacaton to the Casa Grande the desert road leads thru some scattered Indian villages and gives a very good idea of the natural beauty of the region.

|

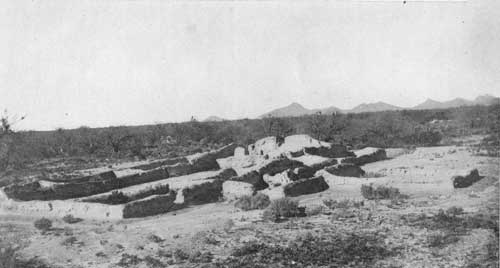

| Casa Grande Ruins before roof was placed over them |

The desert region around Casa Grande is very interesting to the visitor from less arid parts of the country. In general it is a level plain with a horizon of low mountains which Hornaday aptly calls "abrupt risers." Wherever one goes for miles the same conditions prevail of level stretches surrounded by low mountains. The desert here is not the desert of our school geographies. On the contrary it is rather well covered with trees, brush, shrubs, and in the spring, a carpet of wild flowers of many interesting varieties. The mesquite is the largest of the purely local trees, altho in somewhat higher altitudes the graceful palo verde and the sturdy iron wood dispute its sway. The mesquite is a light green, sprawling, crooked tree with finely foliated leaves and sweet racemes of pale yellow blossoms which appear soon after the leaves and soon change into the bunches of long beans which are the staple food of the range stock for some weeks and were in more primitive times the main stay of the Pima Indians. Indeed, one might go farther back and say that they occupied the same place in the diet of the Hohokam, or original inhabitants of the Casa Grande, as only recently several piles of the charred beans have been found in excavating. A smaller sister of the mesquite which is also found in the region is the cat's claw. Aptly named, for the thorns which point from the trunk in the mesquite, turn toward the trunk in the cat's claw, and hold securely anyone who is so unfortunate as to become entangled in the branches.

|

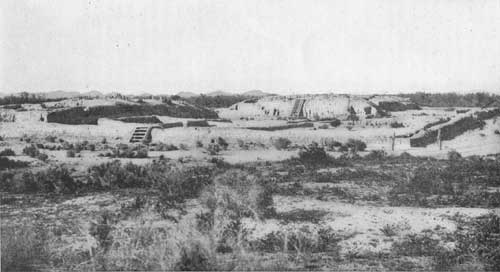

| Casa Grande Ruins, Compound A (Photo by Pinkley) |

The creosote bush is the largest of the shrubs. This grows sometimes ten or twelve feet high, more often four or five, and is a gracefully waving growth, branching from the roots, and bearing an abundance of brown-green, waxy, small leaves, and several times a year, small bright yellow blossoms which later develop into fuzzy gray balls. This bush is ornamental any time of year and is at its greenest in the winter months when the rest of the desert growth is bare and brown. The salt bush also grows freely here. This is often called sage brush, but it is not a true sage. This is a small, low growing prickly bush, and has a pleasant soft gray-green color and a pleasing spicy odor. The salt bush is an important stock food as the cattle eat it freely, while no animal will eat the creosote bush. There is very little cactus immediately around the Casa Grande, but in the region round about many kinds grow abundantly and are an integral and attractive part of the desert flora.

Animal life on the desert around the Casa Grande is quite abundant, but like the flora, each species has some means of protection. Desert life at time seems cruel, but it is from start to finish, a selective process, a survival of the fittest. The coyote, the fox and the different members of the hare and rabbit families, have protective coloring as well as swiftness of motion. The little ground rats are just the color of their desert background and can appear and disappear with disconcerting swiftness. They have an amusing habit of standing motionless on two hind feet until it takes close observation to decide whether the object in sight is a dry stick or an animal. The badger, too is sand colored, and rarely gets very far from his hole. Of reptilian life there is almost too much. The rattle snake is well known, but like a gentleman, warns before his attack. The Gila Monster with his mottling of red and black merges surprisingly well into the patches of light and shade under the salt bush, and his well known hiss would frighten away any enemy. Lizards of many varieties are legion, and flash in and out of sight like shadows. Insect life is also on the offensive. The scorpions, centipedes and tarantulas do not hesitate to attack without warning. The smallest and most annoying form of desert life is the ant family, of which we have the well known "57 varieties," each worse than the one before.

|

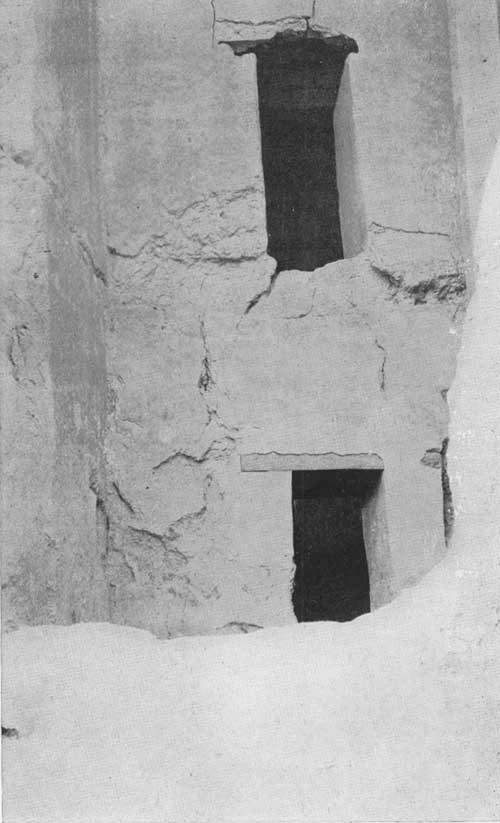

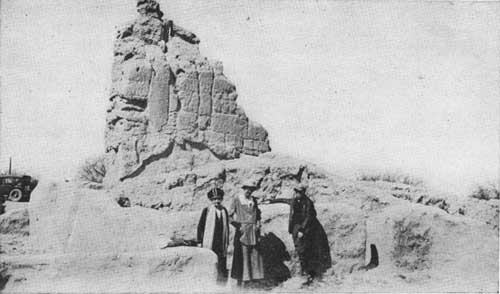

| "Clan House, Casa Grande Ruins" (Photo by Pinkley) |

Bird life at the Casa Grande is very beautiful, many birds nesting here. The Great Western Horned Owl is the largest of the local birds and every year for twenty years at least, a pair have nested and reared two or three little owlets on the walls of the Casa Grande. Occasionally one of these developes a voracious appetite for home grown chicken and has to be disposed of, but for the most part they are very considerate and patronize the neighbor's chicken yards. There are other varieties of owls, also and several different kinds of hawks. Quails and doves are here in numbers, and the interesting road-runner or chaparral cock is often seen. Of song birds three varieties of thrashers fill the air with music. The cactus wren, flicker, flycatcher and beautiful phenopepla (shining robe) are common and at times tanagers and cardinals lend their songs and brilliant coloring to the picture.

The Casa Grande itself is a group of ruined walls, with the four story walls of the main building, or "big house" dominating the scene. It has unfortunately been necessary to cover this building with a roof, which spoils the artistic effect, but which is very important for the preservation of the walls for future generations. This building is about forty by sixty feet and the walls stand about forty feet above the desert level. In this Casa Grande are eleven rooms (five on each of two floors and one on the highest story), with an additional five rooms on the ground floor which were filled in at the time of building to form an artificial terrace. The one room on the top floor must have been considered very important as it was gained at a sacrifice of five rooms on the ground floor. Its use was primarily as a watch tower, as from the ramparts above it a watchman could see as far as the vision would carry, but all the rooms were probably used as dwelling rooms. Around the main building are the ruins of many other rooms and groups of rooms, the whole surrounded by an outer wall, making a walled village, or compound, 216 by 420 feet. Most of these outlying rooms are one story in height, but several are two stories, and the group in the southwest corner is three stories high.

This is the main group called Compound A. Scattered within the area of the monument (480 acres) are several other compounds which have been excavated, and an unknown number of older ones, unexcavated, some of which are definitely located, and probably there are even more as yet undiscovered.

|

| Compound B, Casa Grande, Ariz. (Photo by Pinkley) |

Compound B, the second in importance is about 900 feet north of Compound A, and is 165 by 300 feet. This compound presents a somewhat different appearance from A, as here the walls were not filled in to make an artificial terrace, but the terrace was built first, and upon it were reared houses of a more flimsy type. Surrounding these terraces, of which there were two, are rooms as in Compound A, some few of the solid type of wall used commonly in A, but more of a re-inforced type which will be considered later. The other compounds are older, more disintegrated, and consequently more interesting to the archeologist than to the layman. Exception must be taken in the case of the ruin east of the Casa Grande, which is called, for no obvious reason, "Clan House." This is an interesting building with indications of a surrounding wall. In this house there was a series of rooms surrounding an open plaza, and in the room at the end of the plaza which has two doors connecting, is the remains of a chair, throne or altar, around which are many interesting traditions.

A very definite idea of the architectural development of the Hohokam (which means vanished people) has been been gained by long and careful excavation and study. It is probable that upon first coming to this regions and taking out the first crude irrigation ditches from the Gila River, the life was lived mainly in the open with only the low spreading branches of the mesquite as a shelter, perhaps with a loose brush roof formed by weaving a few arrow weeds into the branches above the makeshift beds. The next logical development would have been the use of a ramada, or vath-rop, as the Pimas call it. This is a roof of poles, cactus ribs and arrow weed or Bata Mote, a straight weed which grows along the river, supported upon four crotched poles. Now, let us assume, came a long windy, wet spell, such as occasionally comes even in sunny Arizona. Some bright woman set up against the side of her ramada several straight reeds bound together with arrow weed withes, thus to shield her fire. This must have proven a great comfort, so the next step would have been to enclose three or even four sides of the ramada. There is much adobe soil around the Casa Grande and more caliche or lime like earth which sets into a crude cement. Suppose a hard driving rain which would drive directly thru the brush walls came. Clay, in jars, keeps water in, reasons the woman, why shouldn't clay, on walls, keep water out? So in all probability, some woman exasperated because her fire kept going out, went out and daubed the windward wall with 'dobe. This would have been far more comfortable for dryness, warmth and protection from the burning sun, so came clay on all the walls and also the roof.

|

| Pottery from Casa Grande (Photo by Pinkley) |

|

| Storage jar from a corner of a room in Casa Grande |

In every land in every era, there are, we know, advanced spirits who will always carry an idea a bit further, and so we have the adventurous Hohokam who spread his caliche just a bit thicker. In time this must have demanded a thicker core of re-inforcement, so we find in Compound B, frequently, and in Compound A, once, to our present knowledge, walls with caliche plaster about four inches thick on either side of reinforcing rods of cedar or juniper which must have been floated down the Gila from miles to the east. These core rods were bound together with arrow weed withes. At the same time we find traces of the conservative element who says, "What was good enough for my fathers is good enough for me!" in the form of remnants of brush houses. Now again came the radical, and how often is invention born of the desire to save a little work! The radical in this case says, "It is all a waste of time to cut and trim and carry these junipers such a distance at such a labor cost! I will try a house with walls of caliche alone, without the re-inforcing rods." So he piled his caliche a little thicker, and we find the place in Compound B, where his solid wall outlasted two rooms of the re-inforced type. This was proof enough for most of the tribe as is evidenced by the fact that in the building of the more recent Compound A, only one moss back failed to be converted to the new doctrine, and built his house in the old style with juniper reinforcement.

The roofs had at the same time developed from the open brush roof to a solid well built roof with first layer of straight juniper poles laid closely together, the butt of one next the tip of the other, thus giving equal strength to each part of the roof. Above this, laid transversely, came a layer of sahuaro ribs, or possibly a native bamboo which has since become extinct. Over this again came a thick layer of arrow weed and above this six or eight inches of mud, forming a solid roof impervious to rain or sun, and possessing the added virtue of forming, in multi-storied buildings, the ceiling of one room and the floor of the room above it. The floors were made smooth and lasting by a hard caliche plaster.

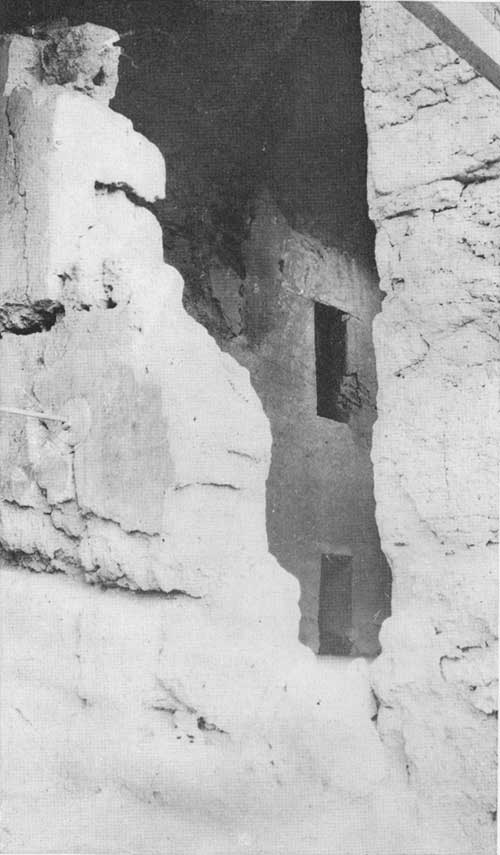

The walls of the Casa Grande are four feet six inches thick at the base and were made without the use of any forms whatever. They were instead, piled up. The caliche of which they are made was puddled with water to a stiff mud, about the consistency which any child would tell you, is the proper stage for mud pies. This was carried in baskets and piled along the indicated lines. By the time one course was laid and patted into shape, it would have dried and become stiff enough for the next course, and thus, there is every evidence to believe, the walls were laid. This theory is strengthened by cross sections of the walls which show that the tops of the courses were curved and much higher in the centers than the sides. Just at the top of every story triangular layers were laid at the sides to straighten the tops of the walls before the roof beams were laid.

|

| Smooth plaster of inner walls, Casa Grande (Photo by Pinkley) |

The walls were plastered with caliche rubbed through a sieve and plastered on by hand, making a hard, smooth, shiny finish which still endures and has become of a reddish hue with age. There are no windows and only low doors. The doors ars small but this does not prove a small people, but rather meant protection from the elements and from enemies. Some rooms had no doors, but must have been entered from the roofs. There were no openings in the surrounding walls which were, in A, eleven feet high.

The life as it was lived by the dark skinned Hohokam, must have been very pleasant on the whole. The fields, irrigated by means of ditches brought from the Gila River, were cultivated industriously. These ditches, of which there are five distinct series in the three miles between the river and the Casa Grande, aggregate a number of miles. They must have been dug by means of flat digging stones, of which numerous specimens have been found, one in each hand loosening and lifting the dirt into baskets, then carrying it away, and perhaps using it to level the small fields. The land was planted to pumpkins, maise and cotton, and these crops were cultivated by means of sharp sticks and crude stone hoes. The crops were gathered into baskets and carried into the village, there to be stored in baskets and in ollas. Wild products were used extensively. Mesquite and cat's claw beans, squawberry and cactus fruits must have been staple articles of diet as were also nuts and acorns that they must have wandered far to gather. A proof of their ingenuity is the fact that there are mortars and metates worn in the living rock in many places where cactus and nuts are plentiful. The pictographs which are plentiful on the mountains near by also indicate that they did not always stay at home. It is probable that rabbits, ground squirrels and quail, and probably other birds and small rodents formed part of their food supply.

|

| Massive walls of Casa Grande (Photo by Pinkley) |

When at home in the walled villages industries of manufacture must have occupied much of their time. Spinning, weaving and preparation of food, as well as basket and pottery making must have kept the women fairly busy, while at the same time the men and boys would have been occupied in grinding out stone implements and in working on their implements of offence and defence. Probably, too, in the long sunny afternoons there must have been abundant leisure for the ceremonies and games which are so integral a part of all primitive life. A very clever and ingenious method of determining the proper time for the be ginning of some of these ceremonies is found in the walls of the Great House itself. In fact we might go so far as to say that the Hohokam had in this, a seasonal clock and a very accurate method of determining the year. At least this is the only theory with regard to a very interesting pair of holes thru the east walls of Casa Grande, which can not be disproved. These two holes, one thru the outer wall and one thru the wall of the inner room are so placed that on the seventh of March and the seventh of October at sunrise, the sun shines thru the outer hole and strikes within a quarter of an inch of the inner hole. Unquestionably the walls have settled out of plumb enough to cause this discrepancy, and there is really no doubt but that when this building was in use, the sun on these dates shone into the inner room as it rose above the horizon. These holes inspired the following poem by Marshall Louis Mertins.

THE WATCHER

Sweet doves a-cooing Cock-a-loo!

By

MARSHALL LOUIS MERTINS

And tawny yellow clouds with skies of blue

Like turquoise sea shells brought from seas afar

To rest beneath the altar! One bright star,

That fleeing from the dawn is caught, and kept,

As one might catch a mermaid as she slept

At dawn, when night's vain shadows flee away

And comes the full orb'd light of golden day.

A watcher gazing thru the east walls

On which the first gray beam of sunlight falls,

Thru weary days had watched the graying sky

At dawning of the morning. Far and nigh

The Palo Varde yellowed, cactus bloomed,

The bright canals ran water, mountains loomed!

But still the people waited in the street,

The plaza and the road with patient feet.

"The earth god, and the goddess of the rain,

Shall we not worship at their shrines again?"

But still no word from that inner place,

Where sat the watcher with the patient face!

Tense moments before the breaking dawn,

A pregnant earth, with skies of flecky tawn,

And praying peoples, bowing low to earth,

Lest great SI-UH-NU see their sinful mirth!

A silence that is felt rests on the place!

The silent people hide a shameful face!

For from within, while waters run, and run,

Breaks forth the welcome cry, "The Sun! The Sun!"

|

| Detail of wall of Casa Grande (Photo by Mrs. M. F. Anderson) |

This prehistoric Indian culture is differentiated from other known cultures by their ceremonial places and implements. There are found occasional small ceremonial rooms, determined by such articles as paint pots, eagle feathers, crystals and images, but there is no place within any compound to correspond to the kiva of other early cultures. The tribal ceremonial place has been identified in recent years by Mr. Frank Pinkley, both at the Casa Grande and at a number of other groups of ruins scattered up and down the Gila valley. These rooms, or rather, open stadia, are eliptical in shape and vary in size with the size of the village. The one at the Casa Grande group is 125 by 80 feet in measurement from the tops of the walls. The long axis is always north and south and the sides slope outward. The floors and sides are smoothly plastered and in the the exact centers of several of them a flat stone was carefully embedded in the floor. Under one of these was found a sea shell and a small polished turquoise fragment.

The dress of the Hohokam was probably extremely simple, simplified to the vanishing point in all probability up to the age of nine or ten years. For adults a loin cloth, and perhaps a cotton blanket or dressed skin with bark or hide sandals, must have constituted the entire wardrobe. On the other hand there is every reason to believe that they wore much jewelry, made for the most part of shell, which was brought at the cost of much effort from the gulf of California. This shell was carved into bracelets, rings, beads and fetishes, the latter usually taking the form of frogs, altho birds and beasts of other kinds are also found. The rings were cut from the conus species of shell, a single "slice," so to speak, forming the ring. The rings were often beautifully carved, engraving usually being the same design. The bracelets were usually, but not always, unoramented. They were ground from the flat shells in such a way that the hinge, ground through, formed a hole to which bangles may or may not have been attached. The fetishes, or small ornaments, were also made of this species. The beads, of which many specimens have been found are usually made of shell, sometimes of olivella shells with the ends cut off, or with a hole drilled near the end. Many beads have been found of tiny bits of shell often not an eighth of an inch in diameter with a hole drilled thru the center. These made beautiful beads, and when an occasional turquoise or pink stone bead was introduced, a string of beads must have been ornaments of which to be proud. Turquoise was evidently highly valued and the infrequent specimens found are smoothly polished and beautifully cut. Many bits of turquoise which must have been used in mosaic work have been recovered. The bracelets were probably used only for children as most of those discovered have been with child burials.

Many of the uses of the different ornaments have been determined from the burials discovered. The usual method of disposal of the bodies seems to have been cremation, the bodies being burned in an open fire and the fragments later gathered up and buried in a small olla with a saucer turned over the top. Sometimes regular burials are found and with them are usually found shells and ornaments and beads and small jars full of favorite foods. In one case a skeleton, perhaps an earlier burial, was found in a sitting posture with head bowed on hands in one of which a bone flute was found and in the other a shell. At the Casa Grande there is strong evidence of the crematory ground, as there is an area of an acre or more on which are strewed burned bone fragments, arrow heads and axes, and burned shell beads which permeate the ground for the depth of eighteen inches.

|

| Corner of Compound A, Casa Grande Ruins (Photo by Mrs. M. F. Anderson) |

The present theory of the occupancy of the Casa Grande is as follows: The Hohokam, probably nomadic in habit, wandered into this valley at some remote time, took a series of canals from the Gila River, lived and died for numerous generations during which the slow development of their architecture took place. Then, harassed by the mountain Indians and suffering from repeated years of drought, they drifted out, not in one great migration, but in a slow filtration which probably took several generations. Family by family or clan by clan they left to become merged with other tribes to such a degree that their tribal identity was probably lost. This process must have continued with ever increasing rapidity, since, as their numbers were lessened they became more and more at the mercy of their enemies. Then after the last remnant was gone the savage mountain Indians refused to occupy the houses and fields which were left to them and went back to the mountains, wantonly burning some of the roofs and leaving the rest to be destroyed little by little by time and the vandal who always has been with us, and unfortunately still exists.

Only one fragment of the departing Hohokam has left even a faint trail. This fragment, one clan perhaps, drifted north, sojourning for a time in all probability in the caves along the Verde River, probably building and inhabiting Montezuma Castle for a time. Then, frightened by a catastrophe in which a very large cliff dwelling near crashed to the canyon below and destroyed a large part of the tribe, the remainder who were living in what is now known as Montezuma Castle, fearing a repetition of the disaster, left in a body and drifted north, finally to merge with the Hopi tribe and form its Pot-ki or Waterhouse clan. In this clan we find legends and indications which tend to substantiate this theory.

The first record we have in history of the Casa Grande, is given by Padre Eusebio Francisco Kino, devoted missionary to the Indians of Sonora. He heard rumors of a Great House on the banks of the Gila, from Indians who lived near San Xavier del Bac where Padre Kino had established a small mission. Finally in November of 1694, Padre Kino went on a trip to visit this wonder of which the Indians spoke with superstitious awe, and tells of it as follows (Kino's Memoirs of Pimeria Alta, Pages 127-129):

The Casa Grande is a four story building, as large as a castle and equal to the finest church in these lands of Sonora. * * * Close to this Casa Grande there are thirteen smaller houses, somewhat more dilapidated, and the ruins of many others, which make it evident that in ancient times there had been a city here. On this occasion and on later ones I have learned and heard, and at times have seen, that farther to the west, north and east, there are seven or eight more of these large old houses and the ruins of whole cities, with many broken metates, jars, charcoal, etc.

Lieut. Juan Mateo Mange reports these ruins in 1697 as follows: We continued west, and after going four leagues more arrived at noon at the Casas Grandes, within which mass was said by Padre Kino, who had not yet breakfasted. One of these houses is a large edifice whose principal room in the middle of four stores, those adjoining its four sides being of three. Its walls are two varas thick, are made of strong cement and clay, and are so smooth on the inside that they resemble planed boards, and so polished that they shine like Pueblo pottery. The angles of the windows which are square, are very true and without jambs or crown pieces of wood and they must have made them without frame or mold. The same is true of the doors, altho they are narrow, by which we know them to be the work of Indians. It is 36 paces long and 21 wide. It is well built and has foundations. An arquebus shot away are seen twelve other half fallen houses also having thick walls and all having their roofs burned.

|

| "Throne" and "Throne Room," "Clan House," Casa Grande Ruins (Photo by Pinkley) |

Kino also mentioned the canals, one of which he thought might have been repaired and used with little effort.

The next authentic narrative comes from the Rudo Ensayo which says, "Pursuing the same course for about twenty leagues from the junction of the San Perdo and the Gila leaves on the left at the distance of one league, the Casa Grande * * * This great house is four stories high still standing, with a roof made of beams of cedar or tlascal and with most solid walls of a material that looks like the best cement. It is divided into many halls and rooms and might well be a travelling court. * * * The Pima tell of another house more strangely planned and built, which is to be found much further up the river. It is in the style of a labyrinth, the plan of which as it is designed by the Indians on the sand, is something like the cut on the margin." (Note: The cut is not given, but a design of a smilar form is found on the walls of the inner room of the Casa Grande, and also, strangely, on a very early Cretan coin.)

The next record is that of Padre Francisco Garces who with Padre Font visited the Casa Grande in 1775. He mentions the tradition connecting this ruin with the Moquis or Hopis, but does not describe them, leaving that to his companion, Padre Font. Font gives the following description: "The Casa is an oblong square laid out perfectly to the cardinal points, and round about are some ruins which indicate some enclosure or wall which surrounds the house, and other buildings, particularly at the corners, where it seems there was some structure like an interior castle or watch tower, for in the corner at the southwest there is a piece of ground floor with its divisions and upper story. The exterior enclosure is from north to south 420 feet and from east to west 260. The interior of the casa is composed of five halls the three equal ones in the middel and one at each extremity larger. The halls are some ten or twelve feet high and all are equal in this respect. * * * In front of the door to the east, separate from, the casa there is another building with dimensions from north to south 26 feet and from east to west 18, exclusive of the thickness of the walls."

Fragmentary reports reach us from time to time, of later visits. In 1825 the Patties, father and son, visited it, and the name of Paul Weaver, trapper, is inscribed on the walls of the ruins in 1832. This by the way, is the only interesting inscription on the walls.

Col. W. H. Emory makes entry in his journal under date of November 10, 1846: "* * * along the day's march were remains of acequias, pottery and other evidences of a once densely populated country. About the time of the noon halt, a large pile which seemed the work of human hands, was seen to the left. It was the remains of a mud house * * * We made a long and careful search for specimens of household furniture but nothing was found except the corn grinder, or metate. The marine shell, cut into ornaments was also found here. * * * No traces of hewn timber was discovered, on the contrary the sleepers of the ground floor were round and unhewn. They were burnt out of their seats in the wall to a depth of six inches. What was left of the walls bore marks of having been glazed, and on the wall in the north room were traced hieroglyphics."

Later reports are by Bartlett, 1852, Lieut. John T. Hughes, 1847, Richard J. Hinton, 1877 and Bandelier who gives a very valuable description, referring the first time in detail to what is now called Compound B. Cosmos Mendeliff records F. H. Cushing's researches in similar ruins, and in 1892 Dr. J. Walter Fewkes gives an exhaustive description.

|

| Southwest corner of Compound A, Casa Grande (Photo by Brundy) |

The Casa Grande Ruin was set aside as a Government reservation by Executive order on June 22, 1892, and in 1900 a resident custodian was appointed for the first time in the person of Mr. Frank Pinkley, who as Superintendent of Southwestern National Monuments still has his headquarters at the Casa Grande. In the winters of 1906 and 1907 extensive excavations were carried on under the direction of Dr. J. Walter Fewkes.

On August 3, 1918 the reservation was made a National Monument. Since 1907 no appropriations have been made for excavation, so the early work of that kind has been carried on by Mr. Pinkley from time to time as the stress of other duties permits. A museum built in 1922 now houses an interesting collection of artifacts and relics.

The traditions of the Pimas regarding these ruins are many, but in whom they claim no relationship to the builders, whom they call the Hohokam or vanished people. They rather believe that the Casa Grande was the abode of a race of demi-gods, and call the chief, who was, they say, magically conceived son of a beautiful mountain woman, Ce-i-lim Stu-ur-dic (Chief Morning Glow). The Casa Grande they call simply Si-i-van Vah-a-ki, or the old house of the chief.

| <<< Previous |

pinkley2/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 22-Dec-2011