|

Capitol Reef

Cultural Landscape Report |

|

HISTORY (continued)

TOURISM AND CREATION OF CAPITOL REEF NATIONAL MONUMENT,

1920-1960

Fruita reached its peak of development in the 1920s. The population totaled 108, a figure that remained stable throughout the decade. An agricultural depression in Utah that began in the early 1920s resulted in many farmers attempting to sell their lands, Fruita being no exception. The 1922-1923 Utah Gazetteer advertised acreage being offered by 11 landowners in Fruita. The Pendletons' land (largely part of the original Hyrum S. Behunin homestead) was combined under the ownership of Clarence (Cass) Mulford during the 1920s, making him the most important orchard grower on Fruita's south end from the 1930s to the 1960s. [17] In 1925 the descendants of Nels Johnson sold the family property to William (Bill) Clarence Chesnut. In 1926 his brother, Alma Chesnut, assembled a 64-acre farm from portions of Leo Holt's homestead, which included the former Holt farm. In 1929 Jorgen Jorgensen sold his property to his son-in-law. G. Dewey (Dew) Gifford. Merin and Cora Smith acquired two tracts of land between 1928 and 1930, totaling 133 acres. After the creation of Capitol Reef National Monument in 1937, a period of relative stability was introduced in Fruita with regard to changes in ownership. All but one small property (Alma Chesnut's) remained in private ownership into the 1960s. Prior to the beginning of World War II, the largest orchards were owned by 'Tine Oyler, Cass Mulford, and Merin and Cora Smith.

| |

| View of Fruita orchards, 1935. Note row of Lombardy poplars. | |

The agricultural depression in Utah coincided with the birth of auto touring as a national pastime. Tourism offered the best hope of reviving depressed local agricultural economies. Beginning in 1921, Wayne County's school superintendent Joseph Hickman, and LDS Bishop E. P. Pectol of Torrey (Hickman's brother-in-law) began promoting the area's scenic wonders through local civic organizations. In 1924 Hickman was elected to the state legislature, and he and Pectol merged their efforts with boosters of the Wayne Commercial Club. Many were convinced that creating a national park in Wayne County would lead to improved roads and communications systems in addition to other economic benefits.

Hickman introduced legislation which resulted in the creation of the State Parks Commission. In 1925 Utah's Governor George H. Dern and other state and local dignitaries visited the proposed Wayne Wonderland State Park to hold ceremonies celebrating its anticipated authorization. As it turned out, the celebration was premature. Hickman died in a drowning accident, ending his legislative efforts, and the park was never authorized nor funded by the state. Still, the activity by park boosters brought about the area's first influx of tourists, with several residents erecting small tourist cabins on their property. By the 1930s their efforts had been incorporated into a regional drive to promote economic development throughout southern Utah. The establishment of a national park in the Capitol Reef area became the focus of their attention during the 1930s.

| |

| Children of Fruita welcoming Utah Governor George H. Dern with fruit tree blossoms, about 1925. | |

Local stockmen opposed the creation of a national park, fearing it would result in the loss of grazing privileges and water rights. Nonetheless, after a decade of lobbying by local interests, President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized the creation of 37,711-acre Capitol Reef National Monument on August 2, 1937. Except for a brief period (July 1953 to November 1954) the monument was administered by Zion National Park (ZION) until 1960.

Until 1935 water use was unregulated on the lower Fremont River, with special concessions in times of shortage. Residents of Fruita diverted water by six primary ditches: Low North Ditch and High North Ditch, Low South Ditch and High South Ditch, the Oyler Ditch, and the Oyler-Chesnut Ditch. The lower Fremont River served four communities: Torrey, Fruita, Caineville, and Hanksville. From 1930 to 1935 water shortages became more acute each year. Disagreements finally led the Hanksville Irrigation Company to cite the other users into the Sixth Judicial District Court for adjudication. Water rights were confirmed to Fruita residents by the action entitled "Hanksville Canal Co. vs. Torrey Irrigation Co." on July 15, 1935. The total decreed water rights for Fruita residents was eight second-feet. [18]

| |

|

Capitol Reef National Monument, 1937. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) | |

In June 1937 Freeman Tanner was appointed river commissioner by the court to record the water distribution from the Fremont River. Tanner reported that a total of 181 acres in Fruita was being irrigated in 1937. In 1941 testimony to the National Park Service (NPS) by Clarence Mulford, a total of 182 acres was described as under irrigation. Both these figures are considerably higher than the amount of land shown as irrigated by the tax assessment records of Wayne County for the same time period (approximately 108 acres). [19] Tanner noted that Fruita land was composed of river-washed gravel covered with a shallow coating of sand. Such land had little water-holding power and required frequent and light irrigation. Tanner reported that Fruita was "almost exclusively planted to peaches." [20] A water user's committee, composed of representatives from each town, cooperated on matters of proper distribution of water. In 1937 the committee chairman was Clarence Mulford of Fruita.

| |

| Clarence ("Cass") Mulford. (undated) | |

Floods continued to be a problem in the new monument. On August 30, 1938 rain fell intermittently for 12 days. Sulphur Creek and the Fremont River flooded their banks, washing out the Fremont River bridge. A report to the monument's superintendent stated, "All property owners in Fruita suffered from the flood and rain. Practicality [sic] the entire peach crop fell on the ground." [21] The following year a flood washed out Alma Chesnut's 8-acre peach orchard, planted on a parcel of land south of 'Tine Oyler's property. It was imperative, in order to retain water rights, that flooded ditches or damaged flumes be repaired to keep them operational. Referring to Alma Chesnut's eight acres of orchards and all the irrigation ditches that were washed out in the flood of 1939, the NPS was advised it would lose its water rights if it did not "start repair and operation of the ditches at once." [22]

Some of the earliest development projects in the monument were associated with flood control and preventing damage to agricultural fields and roads. The first such work was performed by a Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) stub camp from Bryce Canyon National Park that was stationed at Chimney Rock, just west of Fruita, beginning in 1938. [23] Through 1942, crews of up to 50 men were engaged in a variety of projects to improve the monument. Flood and erosion control projects undertaken by the CCC included building basket-type dams along Sulphur Creek. [24] Other CCC work included construction of a ranger station on the west end of Fruita, a highway bridge across Sulphur Creek, and the Hickman Bridge trail.

Improvements were also begun by the CCC on the Torrey to Fruita road (old State Route 24, also called the Capitol Gorge Highway) between Twin Rocks and Chimney Rocks east of Fruita, and on a 2.25-mile section just south of Fruita called the "Danish Hill" section. In these sections, the road was widened from about 11 feet to 18 feet, to meet state requirements for two-lane roads. Minor changes in alignments to the road were also made to improve grade, curvature, and drainage. [25] These projects were only about 70 percent completed when the work was terminated in April 1942 to send the crew to an emergency dam-repairing project at Escalante. [26] The NPS later enlisted the aid of Wayne County and the Utah State Highway Department in 1952 to complete these road work projects. [27]

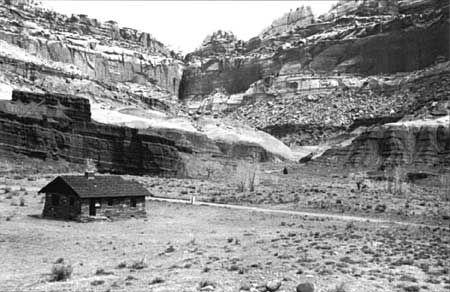

The 1938 plans for the monument's ranger station were identical to those used for a building at Zion National Park (Drawing ZIO-3059A). [28] Initial plans (Drawing CR-2002) called for a three-room, frame building, as monument funds were scarce and salvaged lumber was available. The location of the ranger station was also initially considered to be temporary. Additional funds were found prior to construction and the ranger station was built of native sandstone, much of it quarried near Chimney Rock. [29] Completed in 1940, the L-plan, gable-roofed, single story building is an excellent example of the NPS rustic style of architecture produced by the NPS Branch of Plans and Design during the Great Depression. It sat unoccupied for 10 years because of a lack of water at that location. [30] The building suffered some from acts of vandalism, at one point having all its windows broken out. It was not until 1950 that it was repaired and put to use as a visitor contact station.

| |

| Ranger station, constructed in 1940 by the CCC. Photo taken in 1950. | |

A major impediment to visitation at Capitol Reef National Monument was the primitive road system that approached and traversed the monument. For 20 years after its creation, Fruita residents and monument visitors traveled the 11 miles to Fruita from Torrey on a gravel-covered road (old State Route 24). At Fruita, the road changed to a narrow dirt road that was frequently impassable due to mud (rain or snow melt) or flood damage. Beyond Fruita, the road passed through Capitol Gorge, continuing on to Hanksville. Capitol Gorge was particularly treacherous during late summer. Charles Kelly reported in October 1943: "Three big floods have passed through Capitol Gorge since August, completely wrecking the road. Road crews have been repairing it, but it is still practically impassable." [31]

The coming of the automobile did more than bring tourists to Fruita after 1920. It also provided a viable means of marketing local fruit and produce, and gave added incentive to local farmers to increase commercial production of fruit in particular. The transition from subsistence farming to commercial production led to the introduction of new fruit varieties and methods of planting (e.g., monoculture orchards) that differed from the earlier period of settlement. Fruita farmers trucked fruit and vegetables from their gardens to Richfield, Salina, and other nearby towns. Starting in the 1930s, 'Tine Oyler and Merin and Cora Smith marketed much of their fruit to buyers from Nebraska. Cora Smith recalled, "That was one of the best places. It went to other places, too, but that was the biggest sale place." [32]

Fruita was a patchwork of fruit orchards, cultivated fields, and open pasture. Fruit trees included peach, apricot, apple, plum, and cherry. Early varieties of peach trees were Elberta, Hale, and Crawford; apricot varieties grown were Morpacks and Sweet Pits; plums were Potawatomi, German prune, and Italian prune; cherries were Bing, Lambert, "little pie," Black Tartarian, and others; apple varieties included the Ben Davis, Lodi, MacIntosh, Rome Beauty, Yellow Transparent, Grimes Golden, Red Astracans, and others. [33]

| |

| Alma Chesnut's vegetable garden, orchard, and house (originally the Holt Farm), looking southeast, 1941. | |

If land was not being used for orchard, it was usually planted in alfalfa. Alfalfa was grown to "build up your soil," Dewey Gifford recalled. While farmers in the higher plateau towns grew grain, Gifford, said it was rarely cultivated in Fruita: "The only grain they grew. . . was if an alfalfa field got so old [and they had to] plow it up, they would plant grain for a year of oats, then cut the oats for hay." Hay was not sold commercially, but used to feed local livestock. [34]

In addition to their orchards and fields, Fruita residents typically maintained vegetable gardens, berries (gooseberries, blackberries, strawberries, raspberries), and flowering plants around their houses. Black and English walnut trees were cultivated, as were almond and pecan trees. A variety of ornamentals were planted by early residents. Roses (florabundas, snowball, and climbing) were especially popular, according to Dewey Gifford, who resided in Fruita from 1928 to 1969. "Most everybody had a big bush or two" of snowball roses, he recalled. [35] Wisteria, purple and lavender lilacs, baby's breath, and irises were also popular. A "mock" (Osage) orange tree was located on William and Dicey Chesnut's property. Some residents also planted evergreens. [36] Many of these flowers and trees mark the sites of Fruita's historic homes.

Mulberries are believed to have been introduced to Fruita and the surrounding plateau communities in an effort to cultivate silkworms. During the 1870s and 1880s, Brigham Young encouraged his followers to plant mulberry trees, the first ones being imported from France in 1868. The sericulture venture failed, however, when the railroad brought in Oriental silks. Nonetheless, as a result of Young's campaign, it has been noted that "there is scarcely a town in the south of Utah that has not its avenues of mulberry." [37] The mulberry trees self-propagated and there are still a number in Fruita. Mulberry trees may also have been deliberately planted to attract birds which would have otherwise fed on fruit in the orchards.

| |

| Alma Chesnut's house and stone wall, looking east, 1941. | |

| |

| Animal shed on Alma Chesnut's property, looking northwest, 1941. While the stone wall remains, a garage has replaced the animal shed. | |

Miles from the nearest paved road and without electricity and telephones (until 1948 and 1962, respectively), Fruita was for half a century a close-knit, isolated Mormon community whose economic focus was on farming, unlike the towns of the higher plateau where cattle ranching was the predominant activity. [38] Many Fruita families were related by blood or marriage, and land was often passed from one generation to the next. The number of families living in Fruita ranged during the historic period from 7 to 10. The family names and landowners with longest association to land in Fruita are Johnson, Holt (brothers Leo and Aaron), Chesnut (brothers Alma and William, and William's son Jay), Pierce, Mansfield, Cook, Adams, Oyler, Smith (Merin and Cora), Behunin (Elijah and son Hyrum), Cook, Adams, Jorgensen, Pendleton (Calvin and son Don Carlos), Mulford, and Gifford. At the turn-of-the-century, at least one of the valley residents, Calvin Pendleton, practiced polygamy. His wives were Susannah and Hattie. [39]

Just prior to and after the creation of the monument, a handful of "outsiders" began buying land in the area. These new residents settled in Fruita to take advantage of the spectacular scenery. Dr. A. L. (Doc) Inglesby, a retired dentist and rockhound from Salt Lake City, purchased just under 6 acres from William Chesnut in 1936. [40] After his arrival in Fruita, he was active in seeking monument status for the area. In addition to his residence, Inglesby had two small guest cabins on his property which he rented to tourists, catering primarily to rockhounds like himself. [41] In the Work Projects Administration's Utah, A Guide to the State. Fruita was described as "an eleven-house village of many orchards, set in a pocket surrounded by towering cliffs." The only building the guide found noteworthy was the residence of Doc Inglesby, "built of logs, petrified wood, and ripple-marked sandstone. It is surrounded by a fence made entirely of great slabs of ripple marked stone, bolted together to enclose the rich green of the garden." [42] Inglesby lived on this property until 1959.

| |

| Ranger Charles Kelly, 1950. | |

Another "outsider" who came and stayed for many years was Charles Kelly. Kelly, a printer by trade, writer, and amateur archeologist, historian, and geologist, moved to Fruita with his wife, Harriett, in October 1941 with plans to buy a fruit orchard and devote his time to writing. Kelly recalled in a later interview that "ranch prices went sky high" after the U.S. entered the war: "They doubled almost overnight." [43] For a time, he and Harriett rented a cabin from Doc Inglesby. In October 1942 Kelly wrote to Superintendent Paul R. Franke in Zion National Park informing him that the home of Alma Chesnut had been vacated and inquired about renting the place from the NPS. [44] Zion's Superintendent Charles J. Smith reported in 1943:

In May Mr. Charles Kelly of Torry [sic], Utah renovated and moved into the Alma Chestnut [sic] house in order to safeguard National park interests. Papers are being submitted covering the appointment of Mr. Kelly at a rate comparable to the rental on the Chestnut [sic] property. The Government, thus, would obtain a responsible caretaker at no cost. [45]

Kelly was authorized to rent the place while his appointment as monument custodian was awaiting approval. Thus instead of purchasing land as he originally planned, Kelly served without pay as Capitol Reef National Monument's first custodian in exchange for use of the house and its agricultural land. In 1950 a modest administrative fund of $5,000 was appropriated by Congress which allowed Charles Kelly's salaried appointment as the monument's sole park ranger. (He was made superintendent in 1953.)

Kelly was hard-pressed to provide monument visitors with basic services during this period. At one point, desperate to provide additional recreational areas to visitors, Superintendent Smith suggested siting a small campground and picnic area on "land where Mr. Kelly now lives" if State Route 24 was rerouted along the Fremont River gorge. [46] (The recommendation was not followed; instead, the monument's first campground was established near the ranger station.) For some time Cora Smith had allowed the NPS to place picnic tables for visitor use by the Fruita Schoolhouse on her private land. In 1957 Kelly got into a heated argument with Cora's husband, Merin, over their cows trespassing on his (NPS) property; Cora countered by demanding the removal of picnic tables from the schoolhouse grounds and Kelly had to comply. [47]

Rather misanthropic by nature, Kelly harbored particular contempt for Mormons and once wrote:

I belong to no organizations of any kind whatever, never go out socially, not interested in politics, and hate radios. I really ought to move to California, but if I did the Mormons would say they ran me out of Utah—so I stay just to spite them. [48]

Needless to say, his attitudes did not make him popular among Fruita's local residents. As one example, Kelly viewed the traditional Mormon cooperative system of irrigation with much skepticism, and his writings hint that it truly was not without its problems. Nonetheless his attempt to impose his own solution was unwelcome. In 1957 he wrote:

Fruita has no ditch organization of any kind, and as a result there is always water trouble. The last two men on the ditch have, to do all the maintenance, and then do not get any water. I called a meeting to organize a ditch company, and Clarence [William] Chesnut threatened to throw me in the river for even suggesting such a thing. There is still no ditch company and all residents of Fruita hate me for trying to get the water situation organized. [49]

In spite of poor and unpredictable road conditions, visitors came to the new monument, particularly during late summer when fruit was ripening. Kelly reported in 1944 to Superintendent Smith:

We have had visitors here almost continuously since July 4, most of them from Salt Lake or vicinity and people who have been here before. Most of them like to stay for a week or two, which seems to be characteristic of most of our visitors to this section, particularly when the fruit is ripe. [50]

Summer was not the only time Fruita received large numbers of visitors. The monument had long been a family gathering spot for Easter weekends. The spring blossoms of the fruit orchards provided an especially beautiful backdrop for this holiday. Family picnics were held in Fruita valley and in Capitol Gorge, one favorite activity being "egg-rolling." This local tradition involved rolling colored, hard-boiled eggs down the slopes of the canyon. While Kelly did not document this particular activity, he reported that vandalism (rock graffiti in particular) was sometimes a problem during the Easter high-visitation weekend. Kelly wrote in 1947, "As customary in this section, we will have a flood of visitors from 'the county' on Easter, including a large number of drunken adolescents. . . will do my best to keep them in line, and hope for rain." [51] In the late 1940s and early 1950s most Easters brought 150-175 cars of visitors, totaling more than 1,100 people. [52] (By comparison, the total year's visitation for 1948 was 17,094.) Kelly reported that Memorial ("Decoration") Day was another holiday that brought many visitors from Salt Lake City and the immediate area.

| |

| Flood on Max Krueger's land, looking west, September 2, 1945. | |

In 1945 two major floods occurred in Fruita. On August 12 "the heaviest cloudburst in 17 years" dropped 1.45 inches of rain on Fruita in 20 minutes. Gardens were flooded, leaving them under a deposit of 4 to 6 inches of sand. All ditches were filled in with sand, requiring 2 weeks of work to clear. [53] Kelly reported another devastating flood that occurred on September 2:

We have just had a flood here, the like of which has never been known in this country. . . . Boulders as big as a small house were rolled down with the flood, the course of the river was changed. . . and the flood passed through a large part of the orchard on the Krueger place just below, ruining and washing out many trees. Unfortunately, this occurred just as the peach crop was ready for market, and no help can be had at any price to repair the damage until the peaches are marketed. [54]

A flood in 1948 practically destroyed all CCC-constructed riprap and soil erosion structures. [55] In August 1951 Kelly described the results of another flood:

[It] Completely obliterated our garden and the garden on the ranch below us, depositing 12 inches to 2 feet of sand and rocks, making it forever useless. . . . As a result. . . most of the ditches are completely full of sand and mud. All the wooden flume is gone, and it will require weeks of work to repair the damage. [56]

Floods were such a common occurrence in Fruita that Kelly's successor, Superintendent William Krueger, found the absence of floods more notable than their occurrence: "With the exception of the lack of local flood conditions, the weather for the month has been normal. . . . In the memory of local residents there have been very few years without floods." [57] Flood damage of irrigation systems not uncommonly resulted in replacement of damaged portions with "upgraded" materials during the 1940s and 1950s (e.g., iron pipe replaced wooden flumes).

| |

| Horses were the primary mode of transportation in Fruita prior to the 1920s. From left to right, Cora, Clara, and Carrie Oyler on their horse, "Johnee," about 1915. 'Tine Oyler stands nearby. | |

Livestock were an integral part of the cultural landscape from Fruita's settlement through the 1950s. The presence of a wide variety of domestic animals impacted the "natural scene" by both displacing native species and by creating the need for barns, animal sheds, corrals, and fencing. Fruita's domestic livestock in the early 1940s included 115 head of cattle, 29 horses and/or mules, 205 chickens, 120 turkeys, and 20 pigs. [58] A number of early residents, notably Cal Pendleton, Leo Holt, and Jed Mott, kept bees. [59] Kelly was particularly incensed at the lax attitude of local residents regarding the trespassing of cattle, and in a memorandum on August 3, 1954 to the regional director, he requested that an official order be issued to keep cattle off the monument. Kelly complained:

When campers are kept awake all night by prowling stock and their camps are messed up with fresh manure, they ask me whether Capitol Reef is a national monument or merely a cow pasture. Since the visitors outnumber the natives 1000 to 1 it is our duty to protect them regardless of local opinion. [60]

The problem persisted until Kelly reported in December of 1957 that "Cass Mulford, the worst offender, has moved his herd to Grover. Merin Smith has sold his stock. Mrs. Chesnut has moved her animals to Torrey. The others keep their animals under fence." [61] Local residents may have taken this step in anticipation of the government purchasing their lands. Once the Torrey to Fruita section of Utah State Highway 24 was paved, locals all knew the next portion of the highway was most likely going to go through Fruita. Negotiations were underway to appraise some of the private lands in the valley as early as January 1957.

As much as Kelly was bothered by cattle being on the monument, their presence seems to have discouraged the growth of the deer population in the valley. A 1940 report from Regional Biologist W. B. McDougall stated that,

Cattle overrun the Monument everywhere to the number of 200 head or more. . . . If all domestic animals could be removed from the area it probably would support a herd of 200 or more deer. At present there are not known to be any deer in the area although they are all around it. [62]

| |

| The Holt (Alma Chesnut) house served as the residence of Charles and Harriett Kelly from 1943 to 1959. View looking south, 1948. | |

Ten years later, Kelly wrote that there were "two small herds of deer, about 10 individuals, living in the monument [that] appear to maintain their numbers but do not increase." [63]

In addition to competition with domestic livestock, native populations of wild animals had long been disturbed by local hunting and trapping. Porcupines were particularly destructive to gardens and orchards and were much hated by local farmers. Kelly's first report on wildlife in the monument stated that "porcupines live all over the desert and come in to Fruita as fast as they are trapped off." He also wrote that "owners of private lands. . . all maintain numerous cats and dogs, necessary to keep down rodents. . . . They also trap porcupines, woodchucks, skunks and ringtail cats." [64] Kelly surmised that the valley's fruit, grain, and seed-bearing weeds provided an abundant supply of food for wildlife, "thus increasing the wild population in this small area." Kelly observed that drought conditions on the plateau usually resulted in an increased population of both deer and birds in the lush river valley. At least one species of bird found Fruita inhospitable. During the 1940s pheasants were introduced to the area, but within three years they had disappeared. [65] Kelly attributed their demise to house cats and ring-tail cats. [66]

From 1943 to 1959, Charles and Harriett Kelly lived on the 7-acre parcel of the old Holt farm which the NPS had purchased (after lengthy negotiations) from absentee owner Alma Chesnut in December 1942. At the time of sale, the property included a house (described as "2 living rooms and poor kitchen, adobe brick with rustic covering"), fruit cellar, barn and animal shed, (described as a "stable"), cow and hog corral, a 6-year-old orchard consisting of 200 Hale peaches, 25 Elberta peaches, 12 apples and several apricots, "some grapes and berries," a 5,000 gallon water cistern, and 5,000 feet of fencing. [67] The house was described as having one main room (14' x 20'), a kitchen (8' x 20'), and a bedroom lean-to (6' x 14') on the side of the house. [68] Irrigation water was diverted to the property from the Upper North Ditch, a mile long, unlined ditch in which four or five other Fruita residents also had an interest. Water rights also came with the property, but the ditches had to be maintained and use of the water continued by law in order for the NPS to retain rights.

The agricultural character and use of the old Holt farm experienced little change after it was purchased by the NPS, as Kelly continued to maintain the orchards, vegetable garden, and irrigation system. The fruit cellar was used by Kelly as a radio room and for storage. [69] Over a period of years, however, a number of the early structures were either altered or removed. The animal sheds and corrals once located next to the stone barn wall just west of the residence were torn down by Kelly in early 1943. [70] A row of 11 dead and weakened poplars along the road south of the house was removed in 1947. [71] A two-hole privy, chicken houses and other "old shacks" remained into the 1950s, but were torn down when they outlived their usefulness. [72] The NPS granted Kelly about 15 acres for agricultural use. During the 1940s, the Kellys were able to live on the income from their peach orchard. [73] In addition, they maintained the vegetable garden just northeast of the house. [74]

The house was used into the early 1960s as the monument superintendent's residence, and as such was regarded as woefully inadequate. In 1952 rehabilitation work on the house was undertaken, replacing the lean-to with a living room and bathroom. [75] In 1952 a redwood water tank was placed on the bench above the stone barn wall to supplement the drinking water supply for the property. In 1955 a maintenance garage was built of salvaged materials on the site of the animal sheds, next to the barn wall. [76] A 35-foot house trailer was delivered to the monument in February 1957 and located just north of Kelly's residence to provide living quarters for a full-time ranger. [77] Another trailer was moved alongside the first soon after. Construction of a second two-bedroom addition to the Holt house (on the south elevation) took place from December 1960 to March 1961. [78]

In addition to Doc Inglesby and the Kellys, several other "outsiders" bought property in Fruita in the 1940s and 1950s, notably Max Krueger, Dean Brimhall, and Maxwell and Elizabeth Lewis. [79] Max Krueger was a geologist for Union Oil Company in Los Angeles, California, when he purchased the Oyler property in late 1941. [80] His primary interest appears to have been in the economic value of the orchards. In addition to Oyler's property, Krueger wanted to lease or buy Alma Chesnut's adjoining lands. He first inquired about the monument's plans for the land in November 1941, saying he wished to lease the land for fruit growing. Taking a different tack after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Krueger approached the NPS again in December:

I thought that perhaps now that we were at war that the Government might choose to use its money for other purposes as it is rather obvious that they are not interested in raising fruit or livestock produce. I could put the land to work so if the Government should decide not to buy, would you kindly favor me with the information? [81]

The NPS subsequently informed Krueger that they indeed intended to purchase the property. [82] Krueger held title to his productive orchard land for 20 years, but he did not make Fruita his place of residence. According to Fruita landowner Cora Smith, Krueger and his wife only lived there for one summer during their years of ownership. [83] Tenants maintained the orchards in his absence.

Dean Brimhall purchased 54 acres of land from Orval Mott in 1943 while still residing and working in Washington D.C., where he was in charge of the Research Division of the Civil Aeronautics Administration, U.S. Department of Commerce. [84] He employed local men to operate his farm, most of which was planted in irrigated alfalfa. (Historically, the farm belonged longest to Leo R. Holt's brother, Aaron Holt, who owned and operated it from 1914 to 1939.) Unlike Fruita's other late arrivals, Dean Brimhall was raised Mormon. His father, George H. Brimhall, was once president of Brigham Young University. Dean, however, was known as a free thinker and a critic of various aspects of Mormon doctrine and practice. [85]

Brimhall's property was seen as prime development area by the NPS during the late 1940s, in part because of its developed water system. Kelly was instructed to ask if Brimhall would consider selling the land to the NPS. [86] Superintendent Smith reported to the regional director a few months later that "Mr. Brimhall has firmly stated that he will not sell this tract." [87] Prior to 1953, Owen Davis (owner of the adjoining property) and Brimhall are said to have "piped their water a distance of seven hundred feet." [88] In the late 1950s Brimhall retired and built a residence on the property. It is believed that he first erected a cement block structure between 1955 and 1958; from 1959 to 1960 a wood frame addition was added and the house was "finished," resulting in a two-story, flat-roofed building clad with plywood siding. [89] Brimhall and Doc Inglesby were blamed by Dewey Gifford for the introduction of Russian olive trees to Fruita: "I think they ought to be put in jail yet because [birds] scattered seeds all over the country. . . . I hate them [Russian olives]!" [90]

In February 1956 Max and Elizabeth Lewis of Altadena, California purchased some of the orchards and lands once farmed by Merin and Cora Smith (1930 to 1945), and later by Owen Davis (1945 to 1955). Superintendent Kelly wrote in his February 1956 monthly report that Max Lewis had plans to construct a $50,000 stone house and to drill an artesian well. [91] The same year, the Lewises constructed a new road up Johnson Mesa, intending to build their home on top of the mesa. [92] When Max died on July 13, 1956, Elizabeth became sole owner and chose to concentrate development instead in the area of the original farm along Sulphur Creek. In 1957 Kelly reported that "Elizabeth Lewis is putting the entire upper ditch in a conduit, at her own expense with the idea of having a flow of water all winter." [93] The iron pipeline from the Fremont River followed the original ditch along the new road down the mesa to the valley bottom. [94] Brimhall paid for one-third of the construction costs of installing the 5,200 feet of 14-inch steel pipe, sharing its benefits.

From 1957 to 1958, the house on the Lewis property was greatly enlarged with the addition of a bathroom, kitchen, and combination bedroom/sitting room. [95] In addition to the house expansion, an art studio, carport, fruit packing shed, cowshed, and corral were constructed on the property during this period. An existing basement house was improved to be occupied by the family of an employee, Worthen Jackson. (A basement house was commonly constructed in rural areas of Utah when funds were insufficient to build an entire house. The basement was "capped" in order for the family to occupy it until additional money was available to complete the house.) [96] In 1957 Elizabeth, who was an artist, married another artist, "Batman" illustrator Richard Sprang. [97] Due to her husband's notoriety their house later became popularly known as the "Sprang Cottage."

Both the Brimhall and Sprang residences differed greatly in architectural style and scale from the earlier, more modest homes of Fruita. The Brimhall house was of modern design and materials, its large picture windows affording spectacular views of the surrounding cliffs. The Sprang house (after extensive modifications by the Sprangs) was also modern in appearance and larger than the original house on the property. [98]

| |

| Capitol Reef Lodge, looking north, 1950. Although the 1950 lodge is gone, the row of walnut trees remain on the site. | |

The end of World War II signalled a revival of family vacations in the country. In response to increased tourism in the monument, a number of tourist accommodations were privately developed. The Torrey to Fruita section of State Route 24 was paved in 1957, resulting in a dramatic rise in visitation from 7,500 in 1956 to 62,500 in 1957. Now full-scale motels were needed to meet the demand. Investors Vincent Rosenberger and George Mason purchased part of Inglesby's land and constructed the Capitol Reef Lodge from 1946 to 1950. [99] Cass Mulford erected a small store and gas station on the south end of Fruita, along the main road, in the spring of 1950. [100] Another motel was constructed in the early 1950s by local resident Dewey Gifford [101]

By the 1960s, the NPS was concerned about the proliferation of tourist-related businesses in the valley and in their lack of control over their physical appearance and siting. At the same time privately-owned tourist accommodations were developing in Fruita, the monument sought to expand visitor facilities. In 1950 funds were made available to replace the windows and to do some minor finishing work on the CCC-built stone ranger station, including wiring it for electricity. It was then put to use as the monument's contact station and administrative office. [102] In 1951 cottonwoods were planted in the area to provide shade for an anticipated campground. [103] A 20-site campground was later sited near the ranger station. Culinary water for monument visitors and campers had to be hauled by tank truck from Bicknell (21 miles away) and chlorinated. This practice was continued until 1963. Loads of gravel were dumped on parts of the Scenic Drive (old State Route 24, then called Monument Road) in 1952 "at points which have been dangerous in wet weather," Kelly reported. [104] Revetment projects (willow "spider" jetties) were also undertaken in 1951 and 1952 on the Fremont River and Sulphur Creek to prevent bank erosion and to protect roads and trails.

| |

| Willow "spider" jetties were installed on the Fremont River to prevent erosion of valuable farmland. August 16, 1952. | |

More than beautiful scenery, interesting geology, and a chance to buy fruit attracted outsiders to Capitol Reef National Monument during the post-war period. In the Cold War climate of the early 1950s, the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) encouraged the exploration and milling of uranium through a system of price supports and other incentives. This touched off a uranium boom on the Colorado Plateau. In spite of the U.S. Department of the Interior's attempts to prevent uranium exploration and mining in Capitol Reef National Monument, the AEC cited national security as warranting full development of domestic uranium sources and pushed for prospecting in any potential uranium-bearing formations within the monument. In February 1952 a Special Use Permit was signed between the AEC and the NPS that opened monument lands to uranium miners.

While none of the actual mining activity during the 1950s took place in Fruita, it nonetheless had an impact on the inadequately funded monument by straining its meager resources and primitive road system. Superintendent Kelly, who was vehemently opposed to mining in the monument, finally persuaded the NPS to cease issuing uranium prospecting permits after May 17, 1955. [105] He wrote to the National Park Service director:

Prospectors' jeeps passing through the monument have been averaging 40 a day, with the highest day 65. They all drive with the throttle wide open in order to beat the other fellow to those million dollar claims. . . the gold rush of '49 was never like this. [106]

A month later, Kelly reported that "the bridge near the checking station, built in 1937, collapsed on May 4, due to heavy traffic of uranium trucks." [107] The mining boom also affected the community of Fruita by increasing the demand for meals and lodging. In March 1955, Kelly report ed that Dewey Gifford was making an addition to his new motel "due to good business from uranium prospectors the previous winter." [108]

The changes that occurred to Fruita in response to increased tourism and prospecting posed a dilemma to park managers. Some felt ambivalence regarding the acquisition of private lands and the impact such an action would have on this close-knit rural community. As early as 1938, the NPS recognized that monument headquarters logically belonged at Fruita but that development was hindered by the fact that all desirable land was held in private ownership. It was recommended in 1938 "that the private lands at Fruita be acquired at an early date to prevent unrestricted, unsightly, uncoordinated private developments for tourist service." [109] By 1943 however Superintendent Paul R. Franke expressed strong reservations about this position, and offered an alternative:

The present Superintendent recognizes the conflict of private land but can see no reason why [a] majority of present owners cannot continue to reside and operate their ranches within the monument. With encouragement from the Service these owners can be persuaded to develop and maintain their property in conformity with standards to be established. [110]

Superintendent Franke recognized that the removal of valuable agricultural land from the tax rolls would be a hardship to the local county and its people. He also acknowledged that some small units of land and water would have to be acquired in Fruita to provide space for public use. Five years later his successor, Superintendent Charles J. Smith, urged the regional director to consider Fruita "an exception" before the NPS implemented plans to acquire private lands:

To acquire all inholdings at Capitol Reef, it would be necessary to purchase the land on which the little town of Fruita lies. This land consists almost entirely of highly productive fruit farms. The cost would be great. . . . It is believed too, that this picturesque pioneer Mormon settlement is part of the local scene and adds color to the country. Purchase by the government would decrease the taxable property in Wayne County already the poorest county in point of taxable property in the state of Utah." [111]

Superintendent Smith suggested acquiring the old Floral Ranch on Pleasant Creek for headquarters development (renamed "Sleeping Rainbow Ranch" in the 1940s). He also proposed the acquisition of scenic easements to prevent undesirable development in Fruita by local residents.

The fate of Fruita's private lands was ultimately decided by the Utah State Highway Commission's decision to reroute the new State Highway 24 through the Fremont River gorge. By the late 1950s when the route was decided, the early park managers' fears of unbridled private development had already been realized. Fruita was no longer quite as picturesque as it had been when the monument was first created.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

http://www.nps.gov/care/clr/clr3b.htm

Last Updated: 01-Apr-2003