|

FORT MARION and FORT MATANZAS

Guidebook 1940 |

|

| Fort Marion and Fort Matanzas National Monuments |

ON OCTOBER 15, 1924, two venerable fortresses of the past, Fort Marion and Fort Matanzas, identified with the ancient defenses of St. Augustine and the Spanish in Florida, were declared national monuments. They were administered by the War Department until 1933, when a Presidential proclamation transferred them, along with other historic sites in Federal ownership, to the jurisdiction of the National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior.

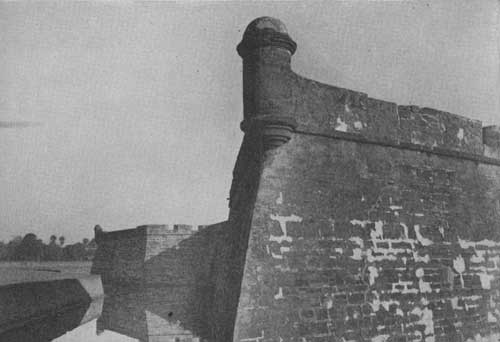

Fort Marion, known to its Spanish builders as Castillo de San Marcos, is a symmetrically shaped four-sided fortress constructed in the manner developed by Vauban, the famous French military engineer. Surrounded by a moat 40 feet wide, its only entrance is across a bridge formerly operated as a drawbridge. The great walls, built of coquina, a soft rock composed of fragments of marine shell, are from 9 to 12 feet thick. Beautifully arched casemates and interesting cornices testify to the good taste and creative imagination of the Spanish builders. The fort contains a council chamber, dungeons, living quarters for a garrison, store-rooms, a chapel, and a room of justice. Nearly all the rooms open on a court about 100 feet square. Fort Marion is situated in a Government-owned tract of land of about 18 acres which also includes the old city gates.

A fee of 10 cents for admission to the fort is charged visitors over 16 years of age, with the exception of members of school groups, who are admitted free up to 18 years of age. Free guide service is available to all visitors. Organizations or groups will be given special service if arrangements are made in advance with the Coordinating Superintendent. The fort is open from 8:30 a. m. to 5:30 p. m.

Fort Matanzas, located on Rattlesnake Island about 16 miles south of Fort Marion, is a small fort about 40 feet square situated in a Government-owned tract of land of approximately 18 acres. It is accessible only by boat. Admission to the monument area is free.

All communications regarding these areas should be addressed to the Coordinating Superintendent, Fort Marion National Monument, St. Augustine, Florida.

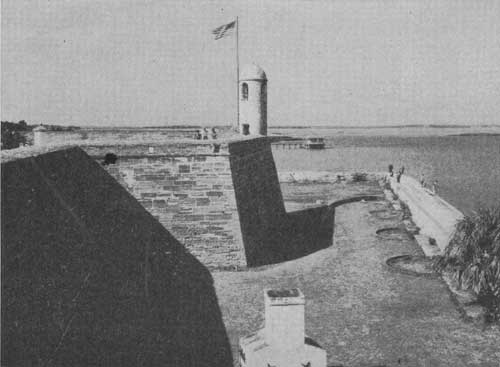

Fort Marion (Castillo de San Marcos), the oldest fort extant in the United States, is rectangular in shape with a projecting bastion at each corner. The moat surrounding the fort has been restored to its original level, the water having a depth of 4 feet or less, varying with the tide. Harris photo. |

Pedro Menendez de Avilés, founder of St. Augustine, in 1565, drove the French from Florida and made it a Spanish stronghold. |

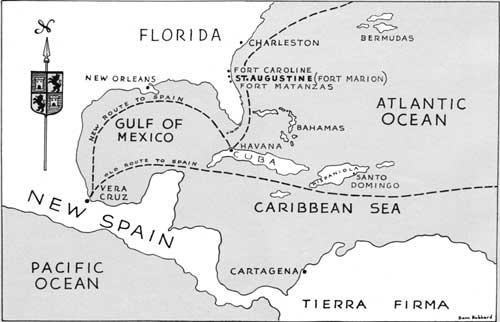

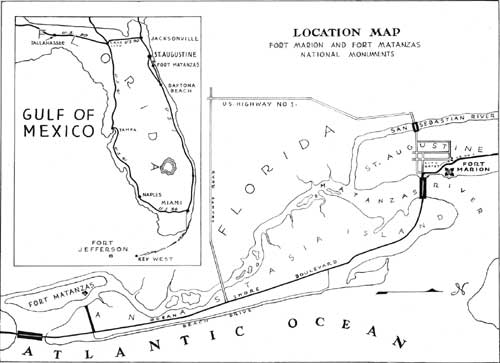

This map illustrates the strategic location of St. Augustine. Spanish treasure fleets abandoned the hazardous route through the pirate-infested Caribbean islands and sailed the "New Channel" past the Florida coast. |

HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

DISCOVERY OF FLORIDA

DURING the fifteenth century the Moors had been driven from the Iberian peninsula; Columbus had charted the course to the New World; and the Spanish nation entered an imperialistic epoch which culminated in the possession of half of the Americas and the domination of the Pacific.

On April 3, 1513, Ponce de Leon, discoverer of Florida, landed near the present site of St. Augustine. Because of its picturesque beauty and since he had discovered the land during the season of Easter, or Pascua Florida, Ponce de Leon called his discovery la Florida, "the Land of Flowers." For a half century thereafter Spanish expeditions to Florida generally ended in disaster, and finally King Philip II banned further attempts. Yet tales of gold mines and great mountains of crystal in the interior still enticed other explorers to the conquest of the region.

THE SPANISH MAIN

IN 1522, the same year that one of Magellan's vessels returned from its voyage around the world, a French corsair seized a treasure galleon bound from Mexico to Spain. This exploit marked the beginning of a lawless era on the high seas in which French, English, and Dutch participated, and the Caribbean islands, through which the Spanish treasure ships sailed, were soon overrun with pirates. Consequently the Spanish navigators were forced to use the Bahama Channel, sailed by Ponce de Leon in 1513. This route carried their ships along the east coast of Florida, thence eastward to Spain. But still the pirates lay in wait for Spanish shipping, and at last came the realization that if Spain did not occupy the Florida salient it was certain to be preempted and occupied by others who would prey upon Spanish commerce.

COMING OF THE FRENCH

IN France, religious wars had broken out. Admiral Coligny, leader of the Protestant or Huguenot faction, planned an expedition which would have a dual purpose. At one stroke the French expected to provide a refuge for the persecuted Huguenots and at the same time to establish a base in the New World for operations against the Spanish. In 1564 the Huguenots built Fort Caroline, near the mouth of the St. Johns River. The news of the French outpost disturbed the Spanish court, and the King of Spain commissioned Don Pedro Menendez de Avilés to deal with the French intruders.

FOUNDING OF SAN AGUSTÍN

ON St. Augustine's Day, August 28, 1565, Menendez sighted Florida. Coasting northward to the St. Johns River, he boldly ordered the French out of Florida. In the meantime Jean Ribaut had brought reinforcements to the little Fort Caroline, so the Spaniards found themselves outnumbered. Thereupon Menendez sailed about 38 miles south to the Timucua Indian village of Seloy and there disembarked. At once the Spaniards set about fortifying the large barnlike communal house which the Indians had given them. With their bare hands and whatever implements they could fashion, the Spanish dug ditches and threw up ramparts of earth. The resulting structure was the forerunner of the great stone Castillo de San Marcos, which marks the height of Spanish power in Florida. The colony of San Agustín (St. Augustine) was established in a formal ceremony on September 8, 1565.

EXPULSION OF THE FRENCH

RIBAUT took the offensive from Fort Caroline and sailed to attack the new settlement, but as his ships rode off the bar of San Agustín a storm arose and the French flotilla was blown southward and wrecked. Taking advantage of reduced garrison at Fort Caroline, Menendez made a forced march in the pelting rain and seized the French stronghold. Meanwhile the shipwrecked Frenchmen were marching up the coast from the south. On September 29 Menendez mustered his small force and hastened to the south end of Anastasia Island to meet them. About 200 Frenchmen were gathered on the opposite shore, and after some parley with the Spanish they surrendered. The Frenchmen were divided into groups of ten, their hands bound, and each little band was ferried across the channel, led behind the sand dunes out of sight of their comrades, and then slain.

On October 12 the same tactics disposed of 150 more Frenchmen, among them the unlucky Ribaut, and thence forward the river was called Matanzas, Spanish for "slaughters." Thus, through Menendez' steel-tempered strategy, the power of the French in Florida was broken.

Built by the Spaniards in 1737, Fort Matanzas guards the south inlet of the Matanzas River—the back door to St. Augustine. The fort is located on Rattlesnake Island, across the river from Anastasia Island. |

This diorama, based upon a contemporary engraving, depicts Oglethorpe's attack upon St. Augustine. The big ships blockaded the harbor, and the English forces encamped upon North Beach (right) and Anastasia Island (left). Harris photo. |

EARLY DAYS OF THE COLONY

SAN AGUSTÍN was then capital of a vast domain. Spain's Florida reached north to Labrador and west to the Mississippi. Still, the outlines of the territory were dim in the mapmaker's mind, and only a few men realized that a continent had fallen into the hands of Spain.

For years after its founding San Agustín consisted of little more than 300 or 400 people, about 100 palm-thatched huts, and a wooden fort. The Indian communal house that Menendez' soldiers had converted into a fortification was soon razed by fire; another fort was built, but the sea washed it away; the next one rotted into oblivion. As the safety of the struggling colony was dependent upon adequate fortification, the early history of San Agustín was a heartbreaking struggle to repair an old fort or build a new one.

San Agustín was never a self-supporting settlement. The primitive agricultural methods of the early settlers were little better than those of the Timucua Indians, who inhabited the region before the white man came. Not for half a century was the meager diet of corn, squash, and fish supplemented by a diversified agriculture which introduced into Florida such products as wheat, beans, potatoes, onions, garlic, citrons, pomegranates, figs, and oranges.

In addition to the dangers of famine and disease, the early inhabitants lived in constant fear of attacks by Indians or pirates.

ENGLISH FREEBOOTERS

As an outpost of New Spain, San Agustín soon received unwelcome attention from other European powers. In 1586 Sir Francis Drake of England sighted the lonely watchtower that stood amid the dunes of Anastasia Island. Before the day was ended Drake's mariners had dragged their guns into position on the eastern shore of Anastasia Island and had hurled a few shot at San Juan de Pinos, the small wooden fort on the mainland. Helpless before the overwhelming English force, the Spaniards fled during the night to the shelter of the forest. The following day Drake crossed the river, took 14 brass cannons and a chest of silver from the fort, then sacked and burned both fort and town.

Phoenixlike, San Agustín arose from the ashes. As the years passed, the city became a fountainhead of Christianity. Franciscan missions reached from the Florida keys north to Port Royal Sound and west to Pensacola Bay. Indian converts were numbered by the thousands, and with these native allies Spain felt there was little danger of enemy encroachment upon the Florida preserve. But the English were not idle, for with their colonies based on great plantations a lucrative Indian trade flourished. Jamestown, 1607; Plymouth, 1620; Boston, 1630; North Carolina, 1653—the British moved southward.

One May midnight of 1668, the call to arms aroused Governor Francisco de la Guerray de la Vega, and he rushed out to find San Agustín in the hands of John Davis and his buccaneers. Alone and unarmed, the Governor made his way to the dilapidated wooden fort, where with about 70 of his garrison he managed to resist the attack of the pirates.

The stairway leading to the terreplein or roof of the fort was originally a smooth ramp up which the guns were dragged. The arch was rebuilt and the steps added about 1886. The iron bars in the windows were added by the Americans during the time the fort was used as a prison. |

IMPREGNABLE CASTILLO DE SAN MARCOS

NOT 300 miles north of San Agustín the English settled Charles Town, South Carolina, in 1670. Within 2 years the Spanish answer to that threat came. At 4 o'clock Sunday afternoon, October 2, 1672, a colorful ceremony took place at the site of the old wooden fort of San Agustín. The Señor Sergeant-Major Don Manuel de Zendoya, Governor and Captain General of the provinces of Florida, broke ground for a stone fort—the Castillo de San Marcos. A week later, Engineer Ignacio Daza supervised laying the first stone of the foundation, and for 84 years from that time the Spaniards and their slaves and their Indian laborers worked to complete the great fortification which would protect not only San Agustín, but all Florida.

The stone castle was ready for use just in time, for the English became more successful in their treaties with the Indians, and the Indian buffer policy of the Spanish became less effective. Sporadic outbreaks occurred on the border, and as the English incited the Indians to rebellion, the Spanish were forced to retreat nearer to the protection of the fort at San Agustín. One by one the outlying missions were abandoned, and by 1680 the Golden Age of the missions was past.

To troubled Europe, in 1702, came the War of the Spanish Succession, or Queen Anne's War, as it was called in America. Governor James Moore of South Carolina used the conflict as a pretext to attack San Agustín. In the fall of 1702, Moore occupied the town without difficulty, since the Spaniards made no resistance but simply moved into the castle in a body and raised the drawbridge behind them. The cannon of the Carolinians were ineffective against the coquina walls of the castle.

When two Spanish men-of-war appeared off the bar of San Agustín, Moore hastily departed overland after burning his ships and leaving a great quantity of stores. Moore's attack revealed the great strength of Castillo de San Marcos, but it also showed the need for walls to protect the town itself, and in the following decade they were built. Thus, when Colonel William Palmer of South Carolina led his expedition against San Agustín in 1728, he got no farther than the gates of the city.

In 1733 James Edward Oglethorpe established the colony of Georgia. In spite of protests from Spanish diplomats, Oglethorpe built Fort Frederica on St. Simon's Island, brought in soldiers and ordnance, made treaties of friendship with the Indians, and prepared for hostilities.

Spain also began to prepare for war. Don Antionio de Arredondo, royal engineer of Spain, was sent to San Agustín from Havana with instructions to spare no effort to put the town in a good state of defense. Arredondo pushed the construction of the castle with renewed vigor, building the bombproof, symmetrical arches which do so much to enhance the beauty of the fort. He also repaired and strengthened the wall around the city.

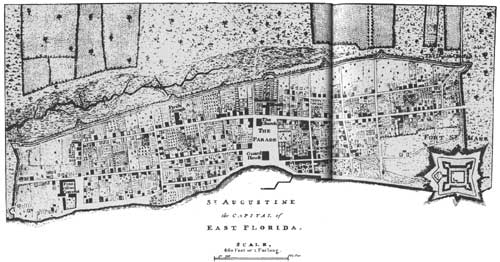

Jeffery's 1769 map shows the wall surrounding the city as it appeared during the English occupation of St. Augustine. The wall was built soon after Moore's attack in 1702, and consisted of a ditch and earthwork planted with thorny Spanish Bayonet (yucca). The wall extending from the fort westward was also palisaded. On the projecting redoubts, some of which were built of stone, cannon were mounted. |

TORRE DE MATANZAS

AT Matanzas Inlet, the southern entrance to San Agustín, a small wooden blockhouse had been in service for a long time. Engineer Arredondo pointed out the immediate need for a stronger defense at that point, but Governor Montiano demurred, contending that additional fortifications could not be built without royal permission. Arredondo finally persuaded the Governor to authorize the construction, and in 1737 the stone Torre de Matanzas was erected. It stands today as Fort Matanzas in the national monument of that name.

After the fort was finished Governor Montiano and Arredondo diplomatically informed the King of Spain of the erection of the new coquina structure. They explained to him the urgency of the situation which precluded their securing royal sanction in advance. This explanation was accepted, for within a short time commercial rivalry between Spain and England culminated in the War of Jenkin's Ear, showing the necessity for such a fort.

OGLETHORPE BESIEGES SAN AGUSTÍN

OGLETHORPE proceeded against San Agustín early in the spring of 1740. Again the population of the city hastened to the shelter of the castle. The 1,500 soldiers of the garrison and about 1,000 townspeople crowded into the courtyard of the citadel, living in comparative safety if not in comfort.

General Oglethorpe's surprise attack by land and sea was frustrated by the presence of Spanish warships in the harbor and the shallow bar at its entrance, so the Georgian decided upon a siege, thereby hoping to starve the garrison into submission. Establishing batteries upon Anastasia Island and North Beach, the English began to shell the fort and town. Confident of success, Oglethorpe called upon the Spaniards to surrender, but Governor Montiano, with taunting Castilian courtesy, replied that he hoped soon to kiss His Excellency's hand within the castle walls. The enraged general ordered the bombardment renewed with vigor.

Meanwhile, the English suffered from lack of water and provisions. The fierce July sun and the maddening hordes of insects gave them no rest. Oglethorpe's force gradually diminished as more and more of the militia deserted. But most discouraging of all to the English was the impregnability of the fort itself. During the 27 days of bombardment the coquina walls would not shatter, the shot burying itself harmlessly in the soft conglomerate. The Spanish, too, suffered privation within the close confines of Castillo de San Marcos, but their daily routine went on as usual. The garrison chapel was the scene of daily Masses, and occasionally marriages and christenings were solemnized there.

But the condition of the beleaguered was soon to be improved. Through the carelessness of the English blockaders, an expedition from Havana slipped through Matanzas Inlet, past Spanish Fort Matanzas, and finally arrived with provisions and munitions for the starving and straitened defenders. Disappointed and disheartened with failure, the English left San Agustín on July 28, 1740, and returned to Georgia.

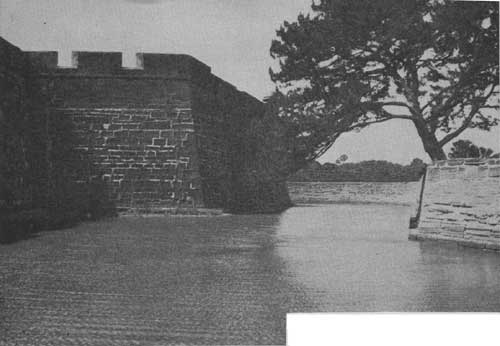

Here a cedar tree almost spans the moat as if reaching toward the fort for strength and support. (Fort Marion.) |

Fort Matanzas silhouetted against the summer sky evokes thoughts of Spanish dominion in America. |

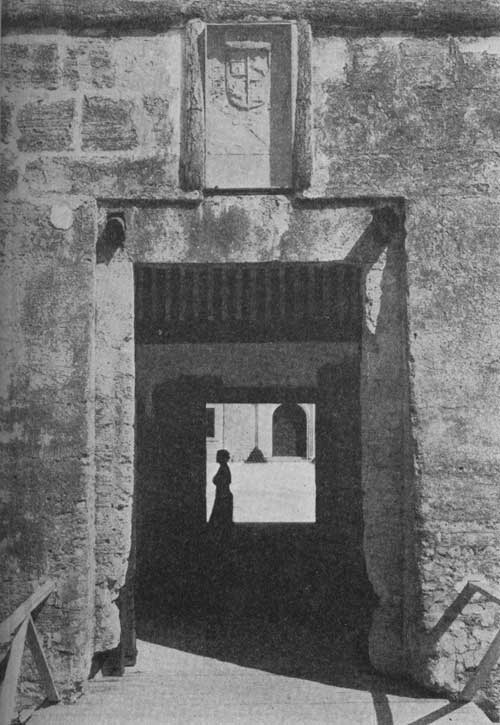

Over the one entrance to Fort Marion is a tablet, erected in 1756, bearing the royal coat of arms of Spain. The pulleys for raising the drawbridge are seen over the doorway. |

Originally, entrance to the fort was by means of drawbridges across the moat. On the left is a small outer fortification called the ravelin, which prevented direct gunfire into the entrance of the fort. |

Headquarters building at Fort Matanzas is located on and near the southern end of Anastasia Island. |

Visitors inspect the rebuilt garrison chapel doorway, originally designed by a Spanish engineer in 1785. Almost all the rooms open into the courtyard, which is about 100 feet square. Rooms were used variously as quarters, storerooms, and prisons. In many of the rooms the English built a second floor. |

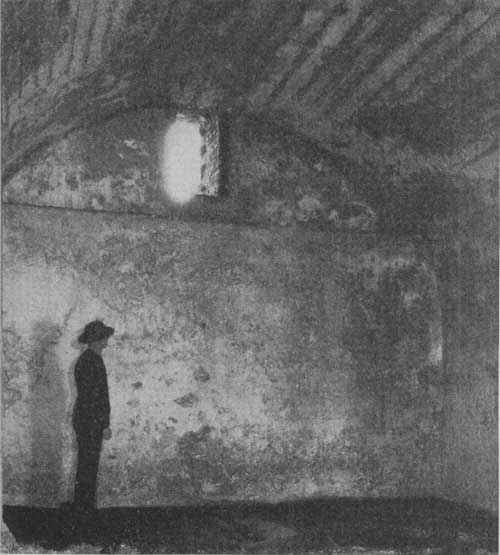

A cell in Fort Marion. |

Osceola, famous Seminole chief, was imprisoned at Fort Marion. Reproduced from an engraving after the painting by Catlin. |

ENGLISH FLORIDA

ILL LUCK in Cuba finally loosened Spain's grasp upon Florida. Havana was captured by the English in 1762, and Spain traded all Florida for that city a year later. Early in the year 1764 the Spaniards departed in a body from the place they had defended for 200 years—a settlement which they had built from a few palmetto huts into a walled town of nearly 900 houses, defended by a stone fort that was one of the military marvels of North America.

St. Augustine (as the English now called it) flourished under the new rulers. A vast plantation system extended itself along the east coast of Florida, and the King's Road was built to connect the isolated communities. Great ships rode off the bar of St. Augustine awaiting rich cargoes of indigo, cotton, and naval stores.

THE REVOLUTION

IN 1775 came the American Revolution, with Florida remaining loyal to the British Crown. When the news of the Declaration of Independence reached St. Augustine, His Majesty's subjects, like the American "Liberty Boys," built a huge bonfire but for a different purpose; in it they burned effigies of Samuel Adams and John Hancock. Thousands of Loyalist refugees fled to St. Augustine, and the town soon became crowded. St. Augustine was the military headquarters for the entire British Department of the South, and regiments were formed to fight against the American forces. Frequent forays into Georgia brought back hundreds of cattle for feeding the English troops garrisoned at Castle St. Mark (the British name for the Castillo de San Marcos) and for the province in general. When the English besieged Savannah, the Tory East Florida Rangers were in the attack and later took part in the reduction of Charleston (Charles Town).

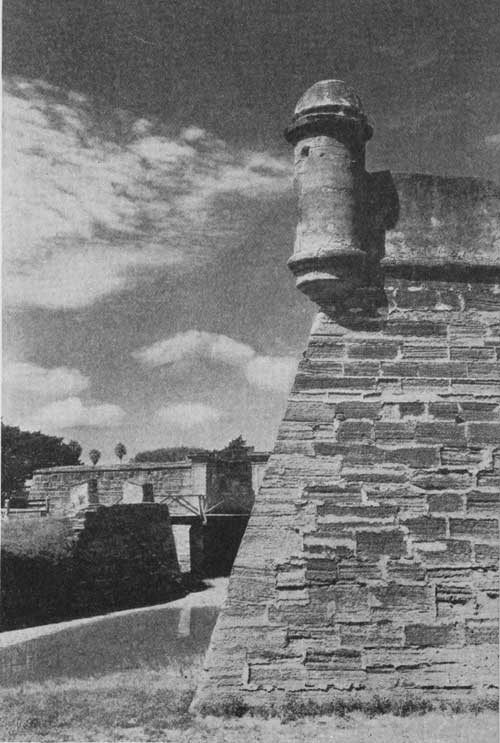

Fort Marion, the oldest existing masonry fortress in this country, commands the harbor entrance at St. Augustine. In the distance beyond the sand dunes of North Beach, is the Atlantic Ocean. The north point of Anastasia Island is seen at the right. Though it has flown the flags of four nations, Fort Marion has never been taken in siege or battle. |

AMERICAN PRISONERS AT CASTLE ST. MARK

AFTER the fall of Charleston in 1780, a number of prominent American citizens were paroled by the English. Soon after, in direct violation of their parole, the Americans were taken to St. Augustine. Among this group were Middleton, Rutledge, and Heyward, signers of the Declaration of Independence. Most of the Americans accepted a new parole, but the venerable Christopher Gadsden, Lieutenant Governor of South Carolina, indignantly refused. For 11 months Gadsden lay in the fort's black prison—for long intervals with not even a candle to light his dreary solitude. During Gadsden's imprisonment in Castle St. Mark, the famous British spy, Andre, had been captured near New York by the Americans and condemned to death. Gadsden was told that if Andre were executed he, Gadsden, would be hanged in retaliation. These threats failed to break the Carolinian's spirit, and the fearless old man eventually was released. Other Patriots fared less harshly, as many prominent Loyalists supplied them with simple luxuries. Andrew Turnbull lent them his English newspapers; Jesse Fish sent oranges and lemons from his world-famous grove on Anastasia Island.

On July 4, 1780, the prisoners had permission to eat together. One feature of the menu was a giant plum-pudding on top of which the prisoners surreptitiously placed an American flag. Inspired by the occasion, Captain Thomas Heyward composed a lyric, and at this Fourth of July Patriot dinner in British St. Augustine was heard for the first time the hymn afterwards sung all the way from Georgia to New Hampshire:

God save the thirteen States,

Thirteen united States,

God save them all.

The verses were set to the familiar tune of "God Save the King," and the British guards, peering through the windows, wondered greatly at what they took to be the rebels' sudden return of loyalty to King George.

SPAIN'S LAST OCCUPATION OF FLORIDA

ENGLAND held the colony of Florida for only 20 years. Then into the harbor of St. Augustine came one of His Britannic Majesty's ships bringing news of the treaty of 1783. Spain had yielded Jamaica to England, but in exchange England had returned Florida to Spain.

The empty houses that the English had left in St. Augustine did not fill rapidly until Governor Zespedes offered land grants to any settlers who would swear allegiance to the Spanish Crown. Thereupon, the town soon became enlivened with frontiersmen whose English names struck a cosmopolitan harmony with the Spanish and Irish names of officials and churchmen. The castle was again strongly garrisoned, but this time the old fortress merely furnished a background for military pomp and pageantry. Spain's star of conquest was descending, and no longer did the nation rank as a great world power. During the War of 1812, American troops occupied Amelia Island and went to the gates of St. Augustine itself without being checked. Again the Spanish withdrew to the safety of the walled city of St. Augustine and Castillo de San Marcos. The American troops were recalled, but a few years later Spain was to lose Florida permanently.

UNDER AMERICAN SOVEREIGNTY

ON the morning of July 10, 1821, the Stars and Stripes replaced the red and gold banner of Spain over the battlements of Castillo de San Marcos. Four years later the Castle was renamed Fort Marion in honor of South Carolina's Swamp Fox of Revolutionary fame, General Francis Marion.

Accession of Florida by the United States, however, did not bring the cessation of internal conflict. Florida settlers coveted the rich lands occupied by the Seminole Indians and demanded the removal of the Indians to the west. The Seminoles, run away Creeks who had come to Florida about 1750, refused to move to the western reservations. Efforts of the United States to mollify the enraged Indians failed and the Florida War broke out. During the next decade Fort Marion resumed its role of military post. As most of the engagements took place in middle Florida, troops were continually leaving the ancient fortification as the Seminoles were driven back into the interior, until finally the garrison was hardly large enough to man the guns.

OSCEOLA CAPTURED

OTHER methods to end the war having failed, in 1837 Osceola, one of the most powerful Seminole Indian leaders, was captured under a flag of truce. He was taken to Fort Marion and there imprisoned in one of the northwest rooms. Later he was removed to Fort Moultrie in Charleston Harbor, where he died. Other captured Seminole leaders were more fortunate. Coacoochee and Talmus Hadjo starved themselves so that they were able to squeeze through the small loophole in their prison, and lowering themselves to the moat with a rope made from bedding, escaped. It was not until Coacoochee was recaptured that the war ended in 1842.

WAR BETWEEN THE STATES

THE War Department of the United States in 1825 had declared Fort Marion useless for defense purposes against modern artillery, but 10 years later reversed its decision and built a hot shot furnace and a water battery along the east front of the fort. Army engineers replaced the 140-year old seawall in front of the town, but little work was done to the fort itself. When Confederate volunteers marched into the sallyport of Fort Marion in 1861, the fort was a vacant, dilapidated old structure. Its solitary defender was the man who held the keys. Under protest he delivered them to the Confederates, who occupied Fort Marion for 14 months. On March 8, 1862, as a Federal naval detachment sailed into the harbor under a truce, a white flag was unfurled from one of the fort bastions, and at the wharf the officer commanding the landing party was met by the mayor of St. Augustine, who surrendered the city, informing the Union forces that the Confederate troops had evacuated Fort Marion the night before. Since St. Augustine women had cut down the fort flagpole, another had to be erected before the United States colors again floated over the battlements.

Only entrance to the city in Spanish times was the City Gateway at the north. Its drawbridge was raised after the sunset gun was fired. About 1830 the bridge was replaced by a coquina causeway. This historic City Gates seen here, built about 1804, are now part of Fort Marion National Monument. |

Archeological excavations on a line extending west from Fort Marion toward the City Gates revealed the remnants of eighteenth century fortifications. This photograph shows remains of the east walls of the westernmost redoubt, called "Cubo." The horizontal base logs are cabbage palm, as is the palisade immediately to the right. |

WESTERN INDIANS

DURING the latter part of the 1800's the fort again became an Indian prison. A number of recalcitrant Indian leaders from the Western States, including Geronimo's band of Apaches, were imprisoned here; but the fort became more of a school than a jail. It was at Fort Marion that Capt. R. H. Pratt conducted educational experiments that led to his later establishment of Carlisle Indian Training School in Pennsylvania.

FORT MARION AT THE TURN OF THE CENTURY

THE Spanish-American War period (1898-1899), during which time about 150 court-martialed American soldiers were committed to Fort Marion, marked the last years of the fort as a military garrison. St. Augustine was no longer a frontier settlement; it had become a resort town. The sunset gun, which from the early days of Spanish dominion had thundered its salute to the colors, was heard no more. The fort itself was abandoned as an active post and arsenal. Today it constitutes one of the most interesting historic ruins within the bounds of continental United States.

This eastern wall of the fort shows scars of Oglethorpe's bombardment in 1740. The moat on this side was filled in and a water battery erected during the 1840's. In the foreground is a hot shot furnace in which cannonballs were heated cherry-red for firing at wooden ships. |

LOCATION MAP — FORT MARION AND FORT MATANAZS NATIONAL

MONUMENTS

(click on image for a PDF version)

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> |

1940/foma/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 20-Jun-2010