|

CHICKAMAUGA & CHATTANOOGA

Guidebook 1940 |

|

Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park

ON SEPTEMBER 19, 1895, Adlai E. Stevenson, Vice President of the United States, spoke to a group of people gathered to dedicate the Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park. Mr. Stevenson said, ". . . Today, by Act of the Congress of the United States, the Chickamauga-Chattanooga National Military Park is forever set apart from all common uses; solemnly dedicated for all the ages—to all the American people . . ."

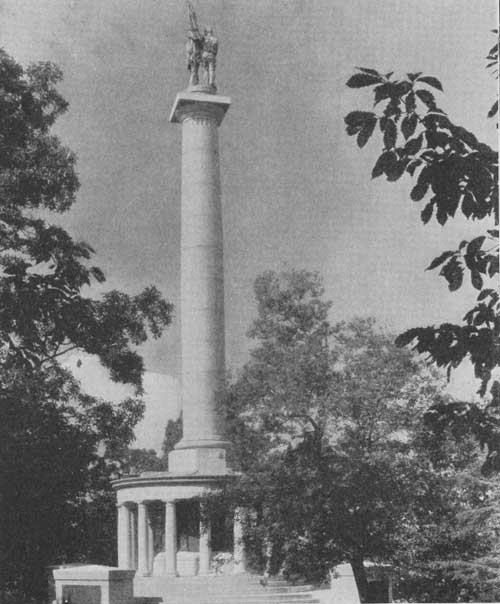

The park dedicated at that time has since grown to be the largest of our national military park areas. It contains parts of the battlefields of Chickamauga and Chattanooga, Civil War engagements severely contested in the latter part of 1863. From its inception in 1890, when Congress established the area as a national military park, the park has represented a cooperative effort of Confederate and Union supporters. This closely paralleled the growth of Chattanooga following the Civil War, when large numbers of northerners and southerners moved to the growing industrial city. Today, the statue of reconciliation surmounting the New York monument on Lookout Mountain, depicts a Union soldier clasping the hand of a Confederate and seems to symbolize a reality carried out both in the park and community growth.

Just as the park development represented both Confederate and Union achievement, so did the battles which it commemorates represent dual measures of success for the participants. The Confederate victory at Chickamauga, perhaps its greatest success in the West, gave new hope to the South. But at Chattanooga, Union forces blasted this hope and permanently secured control of the strategic town. This battle virtually completed the Union occupation of the Mississippi Valley, cut the communications of the Confederate armies in the West from those in the East, and opened the way for the capture of Atlanta and the March to the Sea.

One may obtain an aerial view of the Moccasin Bend of the Tennessee River from Point Park on Lookout Mountain, as well as a panorama of the battlefields surrounding Chattanooga |

Chattanooga at the time of the war was a sprawling village. This view made in 1863 shows Lookout Mountain in the background. (Signal Corps, U. S. Army) |

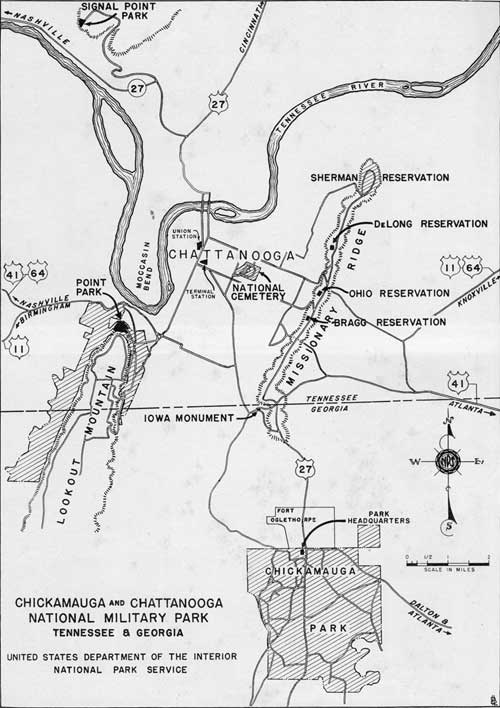

The various units of the park, covering 8,500 acres and including the battlefields of Chickamauga, Orchard Knob, Lookout Mountain, and Missionary Ridge, are within easy access of Chattanooga, Tenn. The Chattanooga National Cemetery, established by order of Major General Thomas in 1863, is close to the center of the city. Visitors are urged to go to Point Park on Lookout Mountain as soon as possible after their arrival in Chattanooga. From the Adolph S. Ochs Observatory and Museum there, all the battlefields can be viewed and complete orientation obtained. An attendant is on duty to assist the visitor. At the northern entrance of the Chickamauga battlefield is the administration building of the park, which also houses the library and museum, devoted principally to Civil War materials. Park employees here are ready to extend every courtesy and assistance to the visitor.

The Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park, in addition to its historic interest possesses considerable scenic attraction. The views from Point Park and Signal Point are exceptionally picturesque. Both in the Chickamauga and Lookout Mountain areas, the visitor will find numerous trails and bridle paths for his use and enjoyment.

All communications pertaining to this area should be addressed to the Superintendent, Chickamauga and Chattanooga National Military Park, Fort Oglethorpe, Ga.

The Civil War in the West

THE CIVIL WAR in the West was motivated by two major plans of the Union forces. One was to drive a wedge through the Confederacy along the Mississippi River. The river offered a natural avenue of transportation and supply. Union control of it would virtually split the Confederacy and prevent the reinforcement and supply of the armies east of the river by those west of it.

The Federal Army built this trestle bridge across the Tennessee River during the Chattanooga campaign. (Signal Corps, U. S. Army) |

The second objective was to drive another wedge through the Confederacy along the railroads through Chattanooga and to the Atlantic Ocean. As Vicksburg proved to be the focus for the Union drive along the Mississippi, Chattanooga, located at a gap in the Cumberland Mountains, became the focal point of the drive to the southeast.

Early in the war, the Confederate forces west of the Alleghenies had established a defensive line in Kentucky and Missouri. The failure of these States to secede and early Union victories forced a withdrawal to the Tennessee border. Here, where the Cumberland and Tennessee Rivers flow into Kentucky, the Confederate forces were assembled to resist and to advance up the rivers.

On February 6, 1862, Union gunboats which had moved up the Tennessee River from the Ohio, attacked Fort Henry and captured it. A week later a combined naval and land force began an attack on Fort Donelson, on the Cumberland. After a severely fought battle, the fort surrendered.

Fort Donelson opened the way to the capture of Nashville. It also called the Nation's attention to Ulysses S. Grant, the leader of the victorious forces. From Fort Donelson to the capture of Chattanooga, nearly 2 years later, the fortunes of the Union Armies in the West closely paralleled those of Grant.

Following the victory at Fort Donelson, the Union troops moved up the Tennessee River to Pittsburg Landing. The Confederates held Corinth, Miss., at the junction of the Mobile & Ohio and the Memphis and Charleston Railroads. Advancing from this point, the Confederates struck the Union Army on April 6 in the Battle of Shiloh and drove them back toward the river. Before victory could be attained, however, Union reinforcements arrived, and on the following day the Confederates were driven back. Shiloh cost the Confederacy one of its ablest leaders, Gen. Albert Sidney Johnston, who was mortally wounded in the first day of the battle. Both South and North were appalled by the tremendous losses, which gave them a real appreciation of the meaning of war.

Union victories along the Mississippi followed. In the same month New Orleans was captured, and, in June, Memphis fell. The one remaining obstacle to complete Union control of the Mississippi was Vicksburg. On July 4, 1863, the Confederates surrendered this important stronghold.

Meanwhile, Union forces had taken Corinth and had begun a slow advance on Chattanooga along the Memphis and Charleston Railroad. The Confederates then assumed the offensive and moved into Kentucky. The campaign was unsuccessful, but the Union forces were diverted from their advance on Chattanooga. While the Confederates left Kentucky for Chattanooga and then moved to Murfreesboro, Tenn., the Union forces assembled at Nashville. On the last day of December 1862 and the first two days of 1863 the battle of Stones River, or Murfreesboro, was fought, forcing the Confederate Army to fall back to Tullahoma, Tenn. The Union Army then occupied Murfreesboro.

The Importance of Chattanooga in the War

TO THE military strategists, Chattanooga appeared to be a very important point. Located where the Tennessee River passed through the Cumberland Mountains, forming gaps, it offered an opportunity for getting an army into the seaboard States beyond. Furthermore, Chattanooga was an important railroad center. Lines connected Chattanooga with Nashville, Memphis, Atlanta, and Knoxville, and at those points provided connections all over the South. Union control of this point would break an important link in the supply system of the Confederacy.

Perhaps of equal importance, since political reasons often influenced military movements, was one nourished in Washington. Chattanooga was in east Tennessee; east Tennessee was strongly loyal to the Union. Therefore, concluded the political leaders, the loyalty of these people must be supported by military encouragement.

Headquarters Camp, Federal Army of the Cumberland, at Chickamauga. (Signal Corps, U. S. Army) |

The Campaign for Chattanooga

MURFREESBORO, held by the Union forces since the Confederate retreat of January 3, 1863, lay on the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad about 110 miles northwest of Chattanooga. Here the Union Army spent the winter, recovering from the severe losses at Stones River. The Confederates had occupied Tullahoma on the same railroad and southeast of Murfreesboro. The Union commander, Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans, methodically prepared for an advance on the Confederates, commanded by Gen. Braxton Bragg. He reorganized the Federal forces into three corps: The 14th, commanded by Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas; the 20th, commanded by Maj. Gen. Alexander McCook; and the 21st, under Maj. Gen. Thomas L. Crittenden. This entire force was designated the Army of the Cumberland.

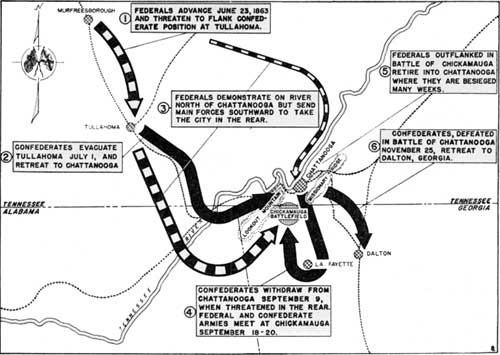

Late in June 1863 the Union Army advanced. By skillful maneuvering against the Confederate flanks, the Union Army forced the Confederates out of Tullahoma and across the Tennessee River to Chattanooga. The next problem of the Union forces was to cross the Tennessee River. Moving three brigades along the river banks north of Chattanooga, the Union commander created the impression that he would attempt to cross in that locality. Meanwhile, the major portion of his army was moved to the south of Chattanooga, and here, with little Confederate opposition, a crossing was made.

Rosecrans' plan to take Chattanooga was to maneuver to the south of the town and break the railway to Atlanta, thereby cutting the main line of supply of the Confederates. If these communications could not be broken, it was possible that a threatening movement against them would force the Confederates out of Chattanooga where they could be met on equal terms.

Keeping his army divided, Rosecrans pushed one corps up the valley toward Chattanooga. The others moved toward Lookout Mountain, south of Chattanooga. But General Bragg was not fooled. Learning of the approach of the Union forces south of Chattanooga, he abandoned the town and took his army to LaFayette, about 30 miles south of Chattanooga and just east of Lookout Mountain. Here the Confederates could guard the railway to Atlanta and be in position to strike any of the three Union corps.

Early on the morning of November 25, 1863, a Union detachment planted the Stars and Stripes on Lookout Mountain. The first man up is said to have been Capt. John Wilson, Co. C, 8th Kentucky Infantry. In the picture he is holding the flag. The other men are, right to left, Sgt. James Wood, Pvt. William Witt, Sgt. Harry H. Davis, Put. Joseph Bradley, and Sgt. Joseph Wagers |

Meanwhile, the Federal corps under Crittenden, which had moved directly on Chattanooga, occupied the town and headed south after the retiring Confederate forces. The Union forces were now in a precarious position. Coming across Lookout Mountain, Thomas' Corps was about 20 miles south of Crittenden. McCook's Corps was fully 40 miles away. To the east of these forces lay the Confederate Army, strategically situated for striking each of the separated corps.

General Bragg then issued orders for attacks on two corps of the divided Union Army, but failure of his subordinates to carry out the commands caused the opportunity to be lost. Finally, aware of the danger, the Union forces were ordered to unite. It was none too soon, as Bragg began to move his forces northward to strike at Crittenden's Corps, in position on Chickamauga Creek. Success of this attack would cut off the entire Union force from Chattanooga.

On September 17 and 18 there took place a race for position, the Union forces desperately pushing northward in an endeavor to unite before the Confederates could attack and secure the first advantage.

Lee and Gordons Mill was the scene of some of the action on the first day of the Battle of Chickamauga. This photograph was made soon after the battle. (Signal Corps, U. S. Army) |

A part of Chickamauga Battlefield as it appeared after the fight. (Signal Corps, U. S. Army) |

Gen. Ulysses S. Grant on Lookout Mountain, 1863. Grant is the figure in the lower left corner. (Signal Corps, U. S. Army) |

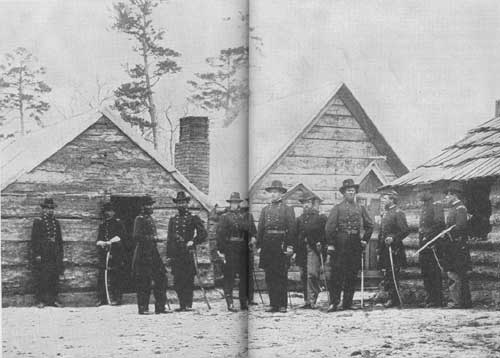

Gen. Joseph Hooker, victor in the Battle of Lookout Mountain, with his staff. Hooker is the sixth figure from the right |

After the fall of Chattanooga, supplies were brought to the Union Army by steamboats. It was necessary to warp the boats up the river through rapids. (Signal Corps, U. S. Army) |

Headquarters of Union General William Rosecrans in Chattanooga during the siege. (Signal Corps, U. S. Army) |

The Battle of Chickamauga

ON THE afternoon of September 18, 1863, parts of the Confederate Army reached the banks of Chickamauga Creek. At Reed's Bridge and at Alexander's Bridge Union cavalry and mounted infantry had arrived to prevent the Confederates from crossing. The first skirmishing of the battle took place at Reed's Bridge, where efforts to stop the Confederates were unsuccessful. At Alexander's Bridge the Confederates were stopped but pushed downstream and crossed at one of the numerous fords. Throughout the evening Confederate troops were arriving at the creek, some crossing and encamping on the west side, others preparing to cross in the morning.

Meanwhile the Union forces to the west of the creek were also marching northward, and by daylight had joined together. From Thomas' Corps on the left of the Union position to Crittenden's Corps at Lee and Gordon's Mill the Union forces now held a continuous line.

About 7:30 on the morning of the 19th, a Union brigade in Thomas' Corps attacked the cavalry of the Confederates, which was in position on their right. Reinforcements were ordered up by both armies, and gradually the battle lines became extended from Jay's Mill southward toward Lee and Gordon's Mill. In the dense woods and the few open fields the fighting raged all day. Only the trees furnished protection to the soldiers as they pushed forward and then fell back. By nightfall the Confederates had driven up close to the LaFayette Road, but efforts to secure it had failed. Union forces had clung desperately to their roads to Chattanooga.

Both commanders were busy on the 19th with the placement of their troops. The Confederate line was established parallel with the LaFayette Road, the left resting on Chickamauga Creek and the right reaching beyond the Reed's Bridge Road. Cavalry troops guarded both flanks. The army had been divided into two wings, the right commanded by Gen. Leonidas Polk, and the left by Gen. James Longstreet, who had just arrived from Virginia. The Union forces were drawn up in a more compact line, not far away. Thomas' Corps was on the left, just east of Kelly Field; McCook's Corps was in the center, facing the LaFayette Road; while Crittenden held the right, with his forces slightly withdrawn. Thomas' forces had strengthened their position by erecting log breastworks.

Chickamauga-Chattanooga Campaign — June 23 to November 25, 1863 (click on image for a PDF version) |

General Bragg's orders for the 20th were for an attack to be started at daylight by General Polk's right division and to be taken up by successive divisions to the left. Bragg hoped to outflank the Union left and cut off the army from Chattanooga. The Confederate attack did not get started until 9:30 a. m. when the extreme Union left was attacked. The charges against the Union breastworks were repulsed with heavy losses, but two Confederate brigades were threatening to outflank the left wing. In response to Thomas' call for reinforcements, General Rosecrans was shifting forces from the right and center to the left. Under the impression that Brannan's division had been moved from the Union center to reinforce the left, Rosecrans ordered General Wood's division to consolidate with Reynold's division in order to keep the line intact. But Wood's division was separated from that of Reynolds by Brannan's, still in position in the Union center. In carrying out Rosecrans' order, Wood moved his division from the front line and passed to the rear of Brannan, leaving a gap in the Union line. Coincident with Wood's movement, the Confederate attack developed. Longstreet's troops made the most of their opportunity and drove through the gap. The right of the Federal line and part of the center were pushed from the field. Rosecrans, McCook, and Crittenden were caught in the break and fled to Chattanooga. Thomas then assumed command of all the Northern forces on the field.

The remaining Union troops were now faced with a flanking movement on their right as well as on the left. Thomas drew in his line and with the assistance of reserve troops that had reached the field, he took up a new position on Snodgrass Hill. Longstreet's forces made several desperate efforts to take this position. The Union troops held, however, until Thomas could pull his other forces from the field and send them through McFarland Gap to Rossville. The forces at Snodgrass Hill then followed, and the Confederate troops held the field.

The battle had been a costly one to both sides. Of the 66,000 Confederates engaged, approximately 18,000 were among the killed, wounded, and missing. The Union forces lost 16,000 out of 58,000 men engaged.

The Siege of Chattanooga

FOLLOWING the retreat of the Union forces into Chattanooga, General Bragg decided to adopt siege tactics to force the surrender of the town. The location of Chattanooga in a bend of the Tennessee River and its approaches covered by mountains and hills were favorable to these methods. General Bragg placed troops on Lookout Mountain from its top down to the Tennessee River. Other forces were placed on Missionary Ridge from Rossville Gap northward to the end of Missionary Ridge and from there to the Tennessee River north of Chattanooga. Connecting these major dispositions was a line across Chattanooga Valley from Lookout Mountain to Missionary Ridge. The only Union connection with Bridgeport, Ala., its supply base on the Nashville and Chattanooga Railroad, was across the Tennessee River, then across Walden's Ridge by rough wagon road and down the Sequatchie Valley. Confederate cavalry troops operated effectively against this line, preventing necessary food supplies from reaching the Union Army. Within a month starvation threatened the forces in Chattanooga.

Aware of the critical situation, Union authorities in Washington ordered troops to the relief of the town. From the Army of the Potomac in Virginia, two corps, under Major General Hooker, were sent. The Army of the Tennessee under Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman was also ordered to Chattanooga. To replace Rosecrans as leader of the Army of the Cumberland, Maj. Gen. George Thomas was chosen. Grant, now in command of all the Union forces in the West, arrived in October to direct the efforts to drive the Confederates away.

Soon after reaching Chattanooga, Grant approved a carefully prepared plan to open a new line of supplies. At 3 a. m., on October 27, 1863, 1,500 men on pontoons floated down the river from Chattanooga, passed the Confederate batteries on Lookout Mountain under cover of darkness, and drifted to the west bank of the river at Brown's Ferry. The force quickly disembarked, drove in the Confederate pickets, and with the cooperation of a force that had moved across the neck of land on Moccasin Bend, constructed a pontoon bridge. The next day supplies began coming in over the new line.

In the meanwhile, Hooker had been ordered to advance from Bridgeport to guard the line of communications just opened. His forces arrived in the vicinity of Brown's Ferry on October 28. At midnight of the same day a Confederate force attacked part of these Union troops at Wauhatchie in an effort to gain control of the line of communications. The attack failed, and the Union forces kept their line open. With supplies now available, Grant spent the next few weeks equipping the Army of the Cumberland and waiting for the arrival of Sherman's army.

View of modern Chattanooga from a Confederate battery position on Lookout Mountain |

The Battle of Chattanooga

ON NOVEMBER 21, Sherman's army had reached Chattanooga. Moving northward around Stringer's Ridge, the army camped in a concealed position, ready to move at the first orders to North Chickamauga Creek. Grant's plans were for Sherman to launch pontoons there, float down the Tennessee River, and cross the river at the mouth of Chickamauga Creek. Then Sherman was to occupy the north end of Missionary Ridge, turn southward, and, with Thomas' forces joining on the right, drive the Confederates away from the railroad line to Atlanta.

While Sherman was planning this movement on November 23, Grant ordered Thomas to advance on Orchard Knob, an advance position of the Confederates in front of Missionary Ridge, in order to test the strength of the Confederates. The position was assaulted and carried. Grant then moved his field headquarters to this position.

Meanwhile, Thomas had been urging that a demonstration be made against the Confederate left on Lookout Mountain. This position had been weakened when Longstreet's forces had been detached and sent to Knoxville. Grant approved Thomas' plan, and Major General Hooker was ordered to carry it out. On the morning of November 24, Hooker's forces moved up the western slopes of the mountain from Lookout Creek. Gradually the small Confederate force was driven back toward the Cravens house, on a bench of the mountain 500 feet from the top. Here, where the Confederates had the protection of earthworks, the fighting was heaviest. The Confederates were finally dislodged from this position and retreated to a new line a quarter of a mile back. During the evening, Bragg, realizing the danger that his troops on the mountain and in the valley now faced, ordered their withdrawal to Missionary Ridge. Early on the morning of the 25th, a Union detachment planted the Stars and Stripes on the top of the mountain.

On the Confederate right wing, Grant's plan miscarried. Sherman, successfully crossing the river, occupied a hill north of the position. Instead of being the north end of a continuous ridge, as it had appeared to the Union strategists a few days before, the hill was separated from the main ridge by a deep gap. On the other side were the Confederates, guarding the tunnel which passes through the ridge at that point. Sherman made no attempt to carry that position that day.

Still determined to outflank the Confederate position, Grant's orders for the 25th were for Sherman to assault the north end of the ridge. Hooker, successful at Lookout Mountain, was to move across the valley and up the ridge through Rossville Gap on the left flank of the Confederates. Thomas' forces in the center were not ordered to move until Hooker had reached Rossville.

At 7 a. m. Sherman began his attacks on the north end of Missionary Ridge. Throughout the day the Confederates successfully resisted them. Meanwhile, Hooker had been delayed in his advance on Rossville. In order to draw off Confederate troops from the flanks and aid Sherman and Hooker, Grant then ordered Thomas' men to take the Confederate rifle pits at the base of Missionary Ridge. Moving out of their positions on a two-and-a-half-mile front, the Army of the Cumberland took the rifle pits. Here the troops were subjected to a severe artillery fire, and with the Confederates in front of them fleeing up the slopes of the ridge, the Union forces instinctively pursued. The Confederate center was broken and fell back from the ridge. In the meantime, Hooker had advanced through Rossville Gap and had assisted in driving the Confederates off. The Confederate forces on the right wing, withdrawn after dark, covered the retreat of the Confederates to Ringgold. Here the last fighting of the campaign took place, after which the Union troops returned to Chattanooga. The Confederates took up a strong defensive position near Dalton, Ga., and went into winter quarters.

The Western Campaign After Chattanooga

WHILE the Chattanooga campaign was in progress, a Union force held Knoxville, Tenn. On November 4 Longstreet was sent to take the town. On November 29 the Union works were attacked by Longstreet, but were successfully held. The Confederates then retreated toward Bristol and left virtually all of Tennessee in Union hands.

Following the battle of Chattanooga, Grant was placed in command of all the Union Armies. Sherman succeeded Grant as commander of the Union forces in the West. General Bragg, the Confederate commander, was replaced by Gen. Joseph E. Johnston. During the winter of 1863-64, Sherman prepared for an advance into Georgia. He assembled 100,000 men and large quantities of supplies. Opposing this force was an army of about 50,000.

Advancing from Chattanooga on May 6, 1864, the Union forces maneuvered the smaller Confederate Army out of Dalton by a flank movement and thereafter Sherman compelled Johnston to keep his army on the defensive and by a series of flanking movements pushed him from one position to another. By July 17, when Gen. John B. Hood succeeded Johnston, the Union forces were close to Atlanta. Here the Confederates assumed the offensive. In a series of battles around Atlanta, the Confederates lost heavily and on September 2 were forced to leave the city to the Union troops.

Hood then moved northward to recover Tennessee and Kentucky, if possible, and to force Sherman to give up Atlanta by attacking his lines of communications northward. Sherman divided his forces and sent one portion under Thomas to stop Hood. The Confederate and Union troops met at Franklin on November 30, and on December 15 at Nashville. In the latter engagement the Confederate forces were defeated in one of the most decisive engagements of the war.

On November 16 Sherman left Atlanta to carry out a plan to march to Savannah, on the Atlantic Ocean. By destroying all sources of supplies that an army needs, Sherman hoped to bring the war to an end. On December 21 he captured Savannah, then turned north through the Carolinas. On April 26, 1864, 2 weeks after Appomattox Court House, the Army of Tennessee surrendered to Sherman.

Points of Interest in the Park

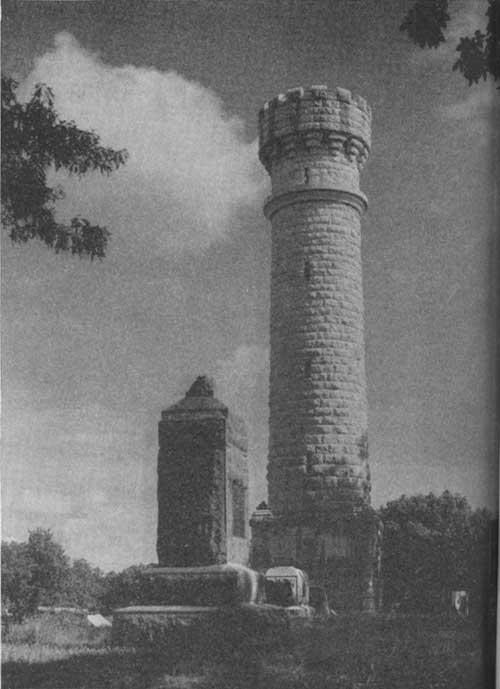

New York State Memorial at Point Park, Lookout Mountain |

Wisconsin State Memorial at Chickamauga |

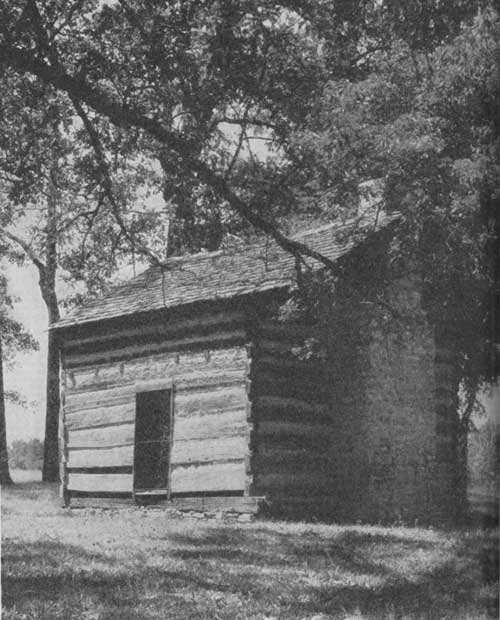

House where the Confederates broke the Federal line |

The Wilder Memorial at Chickamauga |

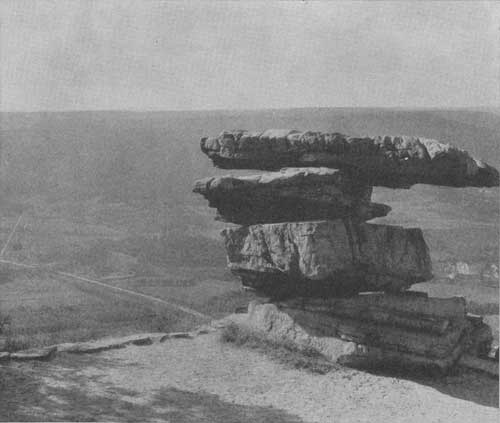

Balanced Rock—Point Park |

National Park Service Administration Building at Chickamauga Park |

CHICKAMAUGA AND CHATTANOOGA NATIONAL MILITARY PARK (click on image for a PDF version) |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> |

1940/chch/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 20-Jun-2010