|

CHIRICAHUA

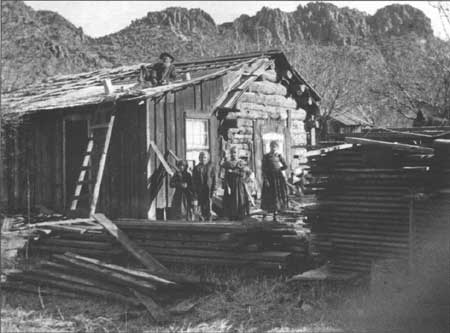

A Pioneer Log Cabin in Bonita Canyon The History of the Stafford Cabin |

|

I. HISTORY OF THE STAFFORD CABIN

A. INTRODUCTION

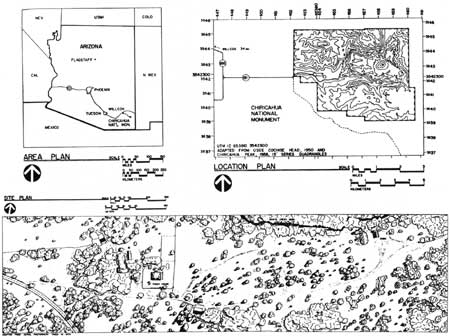

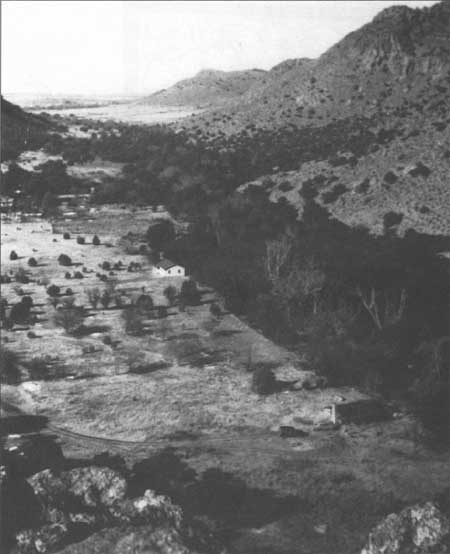

The Stafford Cabin is a log and frame building located in Bonita Canyon, a small drainage from the west side of the Chiricahua Mountains into the dry but productive Sulphur Spring Valley in Cochise County, Arizona. The cabin is individually listed in the National Register of Historic Places (March 31, 1975) and is also contained in the Faraway Ranch Historic District (August 27, 1980), part of Chiricahua National Monument. It is managed by the Superintendent of the Monument.

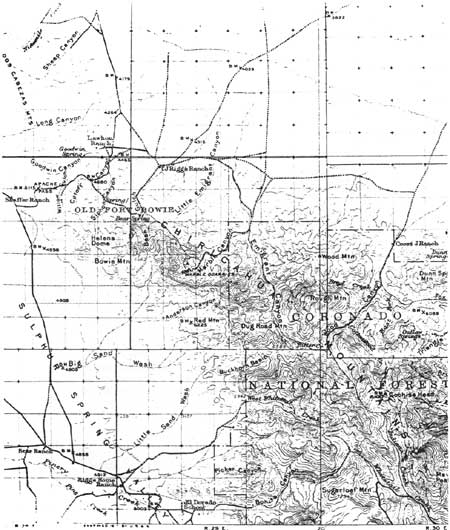

Chiricahua National Monument, established in 1924 to protect the unique rock formations popularly known as the "Wonderland of Rocks" which adorn the upper reaches of this section of the mountains, is surrounded on three sides by the Coronado National Forest, and on the fourth, or west side, by Sulphur Spring Valley, most of which is privately owned.1

1Sulphur Spring Valley is commonly referred to as Sulphur Springs Valley, but the official U. S. Geological Survey name is used throughout this report.

The 110-year-old homestead cabin and surrounding land became part of Chiricahua National Monument in December, 1968. The structure is a two-room log cabin with a stone fireplace and chimney, a shed-roofed "kitchenette" and bathroom addition, an open porch, and an attached garage. The cabin sits on a flat expanse of the canyon once occupied by an orchard, from which a few trees remain. Bonita Creek is located a short distance north of the cabin.

The history of the Stafford Cabin involves a number of facets, from a homestead claim during the Apache resistance to family life in a pioneer environment to its last decades as a guest cottage at a modestly popular dude ranch. Perhaps of foremost significance is the pioneer era, or the Stafford years, 1880-1918, a time when the earliest settlers appeared in the area and developed a ranching and agricultural legacy in the Sulphur Spring Valley. This document will hopefully shed new light on the significance of the Stafford Cabin in the history of the Southwest.

|

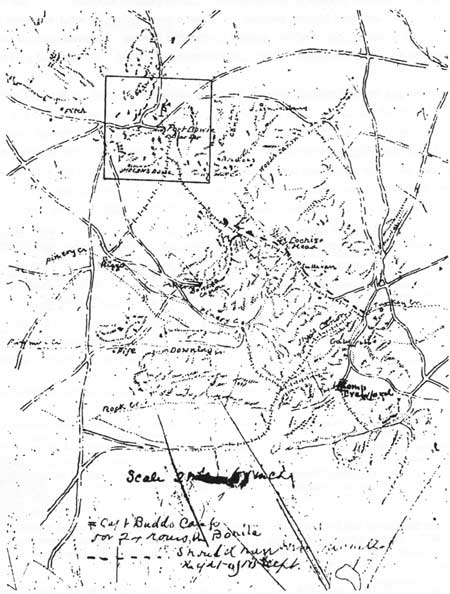

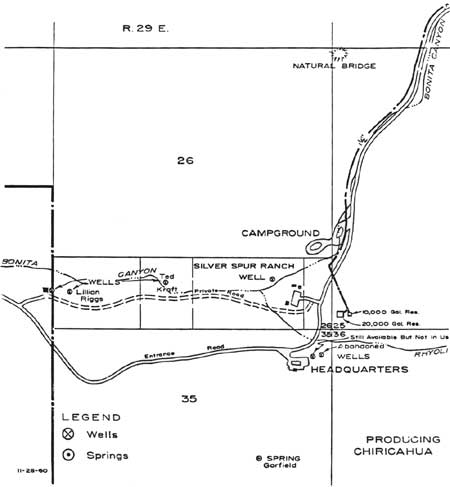

| Location maps of Chiricahua National Monument and Stafford Cabin. (Source: HABS) (click on image for a PDF version) |

B. SULPHER SPRING VALLEY AND BONITA CANYON TO 1880

Sulphur Spring Valley is a wide semi-arid region in the southeastern corner of Arizona bordered on the east by the Chiricahua Mountains. It is noted for cattle ranching and farming with irrigation. Chiricahua Indians, an Apache tribe, inhabited the valley and the mountains from the 1700s until 1876 when after years of warfare and four years of uncertain peace, U. S. troops removed those who did not flee to the San Carlos reservation to the north. However, not until 1886 did the troops succeed in subduing this troublesome band, led by Naiche and Geronimo. During their heyday Indians congregated at Bonita Canyon's spring where they found not only sustenance but a pass over the Chiricahua Mountains, a route that also afforded numerous hiding places.2

2Robert M. Utley, A Clash of Cultures, Fort Bowie and the Chiricahua Apaches. Washington: National Park Service Division of Publications, 1977, pp 9-20; Martyn D. Tagg, The Camp at Bonita Canon, a Buffalo Soldier Camp in Chiricahua National Monument, Publications in Anthropology No. 42. Tucson: Western Archeological and Conservation Center, 1987, p. 22.

The threat of Apache attack kept Spanish explorers and missionaries away from the region, and after the Gadsden Purchase from Mexico in 1853-54 settlers were still somewhat discouraged from entering the valley. Lt. Col. Philip St. George Cooke and his "Mormon battalion" opened a wagon road via San Bernardino and Tucson some years earlier and the Butterfield Overland Mail operated in the area from 1858 to 1861. During the 1850s relations with the Chiricahua Apaches remained fairly peaceful. A number of government survey parties crossed the valley between 1851 and 1855, including one survey of the Mexican border and another seeking a transcontinental railroad route. Evidence of pioneer cattle ranches were found by members of the former expedition.3

3Utley, A Clash of Cultures, pp. 14, 17-20; O. E. Meinzer and F. C. Kelton, Geology and Water Resources of the Sulphur Spring Valley, Arizona. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1913, p. 11.

As tensions between Indians and the military and civilians increased, coming to a head at the battle of Apache Pass in 1862, the United States Army established Fort Bowie at the northern end of the Chiricahua Mountains on July 27 of that year. The fort dominated not only the pass but the source of water at Apache Spring, and provided troops to help make the region safe for white settlers, an often difficult and sometimes impossible task.

Colonel Henry Clay Hooker, who had arrived in the Tucson area with his livestock in the summer of 1869, established the first permanent cattle ranch in Sulphur Spring Valley in 1872, the Sierra Bonita Ranch located northwest of today's Willcox. During the late 1870s a small number of settlers entered the valley, including Louis Prue and Brannick Riggs, both of whom founded ranches in the vicinity west and northwest of Bonita Canyon. By 1880 the main line of the Southern Pacific Railroad reached the northern part of the valley, where merchants and settlers established the town of Willcox.4

4Louis R. Caywood, The Archaeology of the Sulphur Spring Valley, Arizona, Thesis, University of Arizona, 1933, p. 14-15; Roscoe G. Wilson, Pioneer Cattlemen of Arizona, Phoenix: The Valley National Bank, 1951; Meinzer and Kelton, Geology and Water Resources, pp. 12-14.

C. THE STAFFORD HOMESTEAD

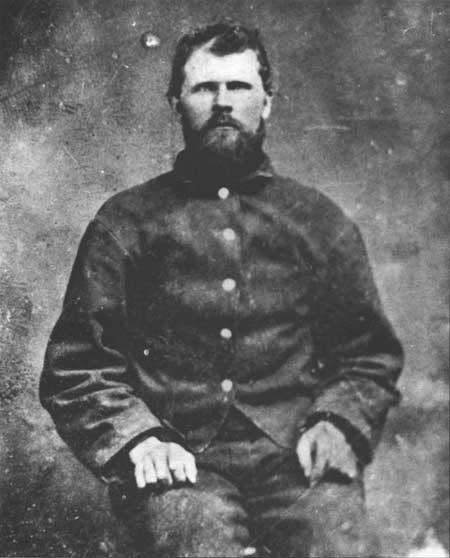

Late in 1880 a man with the uncommon name of Ja Hu Stafford arrived in Bonita Canyon with his new wife, Pauline. Stafford was born on June 2, 1834,5 in Davidson County, North Carolina, to John Wesley Stafford and his wife, Clementine Reid Stafford. Young Ja Hu moved with his family to Kentucky and then Missouri where he lived until 1852, when the not-yet-18-year-old enlisted in the army, stating his age as 21.6

5The date of Stafford's birth varies from account to account. Often it is given as 1836, supported by Stafford's own reports later in his life; Stafford was known to have misstated his age at times. The 1834 date is supported, however, by the 1850 census and an 1872 letter to his brother, in the Stafford Family Collection.

6Stafford's given name appears in many forms on documents and notes about him, likely because of its uncommonness. Some of Stafford's descendants apparently prefer Jay Hugh, a spelling sometimes used in later writings about the man and which appears on his replaced gravestone in the Sulphur Spring Valley Community (El Dorado) Cemetery. Other variations include Jahu, Ja. Hu., Jehu and J. Hugh. The earliest legal documents prove that the original spelling was Jehu, after the Biblical prophet (Jehu was also 19th century slang for a fast reckless driver of a stagecoach or wagon, although there is no indication that there is any connection here). However, this report accepts Ja Hu as the correct spelling, for the reason that it appears with that spelling on all surviving documents written in his hand, including his personal bible, and most of the Arizona-era official documents carry that spelling. Much of the personal information about the Stafford family comes from personal communication, largely letters, phone interviews and copies of original material in the Stafford family, provided principally by Dr. Edward Wheeler of Dallas, Texas and Colonel (Ret.) Tom Kelly of Ft. Bowie, Arizona. The other major source of Stafford family information was V.I.P./Historian Richard Y. Murray of the Western Archeological and Conservation Center in Tucson, through personal communication. Stafford's military record was obtained by Kelly in Record Group 94, National Archives.

After serving five years as a recruit and then private in Company K of the 7th Infantry at Forts Towson, Arbuckle and Washita in the Indian Territory (later Oklahoma) from 1852 to 1857, Stafford commenced to travel around the country. Stafford visited Texas, Arkansas and Kansas Territory, and along the way (possibly in Illinois) he married Dorothy Francis Hicks. He then drove a small herd of cattle to Oregon where he tried his hand at ranching and farming in the Powder River area of Oregon. After about seven years of operating a public house near Baker, Oregon, Stafford sold out his ranch and returned to Kansas a relatively rich man. For a year he owned a large herd of cattle, but sold it in 1873 and bought a number of properties in Garnett, Kansas. He left Garnett two years later and, after trying at least two new careers, including as a Wheel and Wilson sewing machine salesman, he returned only to suffer continuing financial setbacks. Around this time Ja Hu left his wife and daughter, Alice ("Allis" in Ja Hu's spelling), and his stepson, Theodore Hicks, and traveled to Colorado.7

7Many years later in adulthood Theodore reportedly visited the Arizona territory and perhaps his stepfather Stafford. This writing of Stafford's history before arriving at Bonita Canyon, and much of the Bonita Canyon era, is largely based on letters, notes and documents in the family collection, obtained through personal communications with Wheeler, Kelly and Murray.

|

| Figure 1 — Ja Hu Stafford as a younger man. (CHIR 1549) |

In 1879, while in his mid-forties, Stafford went to Manti, in Sanpete County, Utah. There he met Christoffer Madsen, a Danish-born Mormon immigrant to the area. Madsen, his wife, and two daughters had traveled in 1867 as part of a Mormon company on the steamer Manhattan from Liverpool to New York, continuing by rail and riverboat to North Platte, Nebraska. The travelers purchased some sixty covered wagons there and outfitted themselves with necessary provisions. Under the leadership of Capt. Leonard G. Rice, the wagon train left North Platte on August 8, 1867 for Salt Lake City. During the trip the two daughters died, and in September a girl was born in western Wyoming and named Pauline Amelia. The company reached Salt Lake City on October 5, 1867.8

8Leonard Grant Fox, My Story: by Ruth May Fox. Salt Lake City: 1973, pp. 11-13; Wheeler, personal communication.

According to a family story Ja Hu Stafford met 12-year-old Pauline Madsen in the spring of 1880 as she herded cattle barefoot and came to his cabin to get warm. On June 3, 1880, Ja Hu and Pauline were baptized into the Mormon faith in Manti, and probably married at this time, and soon left for Arizona. The couple traveled in a wagon train via Lee's Ferry on the Colorado River. An experienced Stafford helped the ferryman get the train across the river, for which he was given free crossing and a dollar.9

9Journal of Ja Hu Stafford, original owned by Rodney Wheeler, copy provided by Dr. Edward Wheeler; Pauline Stafford to her father, August 6, 1883, Stafford Papers, Chiricahua National Monument.

The Staffords arrived in what was to become Cochise County in the latter part of 1880 and made their way to Bonita Canyon. According to Stafford's daughter, Clara Stafford Wheeler:

Poppa decided that he would go to Arizona to live and he hitched up his wagon. He had an old covered wagon and a span of horses and he went out to Arizona and he came to the Riggs Ranch . . . . [Riggs] had come there three or four years before him. Poppa asked him if there was any place to settle and he told him about Bonita Canyon. . . had water in it and high grass and everything and he thought he'd like it up there so he found a place.10

10Transcript of an oral history with Clara Stafford Wheeler, 1971, originating from Wheeler and given by Kelly to Chiricahua National Monument. Mrs. Wheeler's reference to the date of Riggs' arrival is incorrect; it was little over a year before the Staffords arrived in late 1880.

|

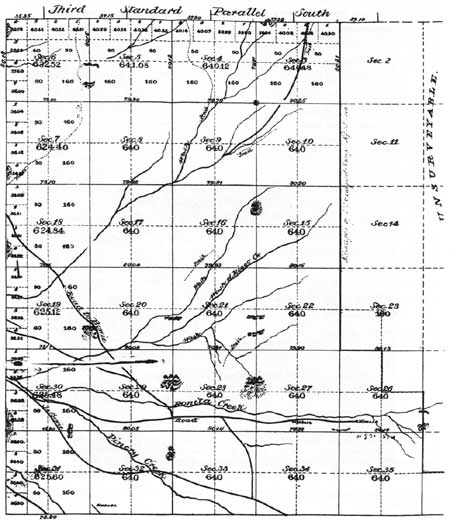

| Figure 2 — Township survey, March, 1882. Stafford Cabin marked as "house" at right. "Cabin" is near site of later Cavalry camp. (BLM) |

On October 17, 1880, Stafford filed for a homestead in Bonita Canyon, a long rectangle of bottom land and mountains consisting of 160 acres, being the south 1/2 of southwest 1/4 and south 1/2 of southeast 1/4, Section 26, Township 16 South, Range 29 East, of the Gila and Salt River Base Meridian.11

11Entry 471, Tract Book, Arizona, Vol. 166, and individual land record jackets, Washington National Record Center, Suitland, MD, as reported in Torres and Baumler; homestead records of the Bureau of Land Management, Phoenix, Arizona.

With winter coming Stafford and his wife must have constructed their one-room log cabin in haste. Stafford chose a site near the southwest corner of the homestead, on Bonita Creek. He built the fourteen-and-a-half-foot square, high-ceilinged structure of large unpeeled logs, an attribute that supports the notion that Stafford was in a hurry. Stafford squared and notched the corners and chinked the openings with wooden wedges and gravelly mud. His daughter Clara described the cabin construction, probably basing her memories on what her father had told her some sixty years earlier:

He took his span of horses and drug logs all the way up where the old picnic ground used to be in the canyon there . . . about a mile above the spring and he cut these logs and skinned them and took most of the bark off them and built the cabin all by himself with the help of mother . . . and he cut the shingles and they called them shakes to cover the house with instead of shingles he makes shakes so the house didn't cost much and there was a fireplace in the house.... 12

12Oral history of Clara Stafford Wheeler. Material evidence shows that Stafford did not peel the logs out of which he constructed the cabin.

A photograph taken some twenty years after the construction of the cabin showed large shakes covering the visible portion of the original roof. The cabin had a dirt floor.13

13Interview with Helen Kenney by the author, November 14, 1990.

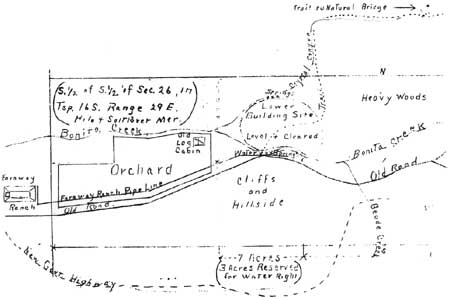

In the southwest portion of the homestead Stafford planted an orchard. To the east, up Bonita Creek, lay other suitable planting areas and a good spring, in what is known today as Silver Spur Meadow; here Stafford planted a vegetable garden. The remainder of the homestead to the north consisted of rocky and mountainous ground with scattered grazing land. 14

14Bureau of Land Management, Phoenix, Fiche 1, Vol. R page 910. A survey map of sections in the area, marking a "house" on Stafford's homestead, was approved and filed July 1882.

Ja Hu and Pauline Stafford became the first to settle permanently in Bonita Canyon. Near the mouth of the canyon lived Louis Prue, a cattle rancher who had come to the Sulphur Spring Valley in late 1878 or early 1879. A few miles farther northwest lived Brannick and Mary Riggs, pioneers who had arrived shortly after Prue. The Riggses raised ten children and their family and descendants have enjoyed prominence in the area for over a century. In a letter to her sister, Pauline Stafford wrote that "for several years after we first came here we only had one neighbor nearer than him [Brannick Riggs]." This "one neighbor" would have been Louis Prue.15

15Pauline Stafford to Clara Madsen, March 8, 1894, Stafford Papers; communication with Richard Y. Murray; Will C. Barnes, Arizona Place Names. University of Arizona Bulletin, General Bulletin No. 2, Vol. VI, No. 1, January 1, 1935. Tucson: University of Arizona, 1935, p. 61, states that Prue arrived in December, 1878, and was the first settler in the area.

|

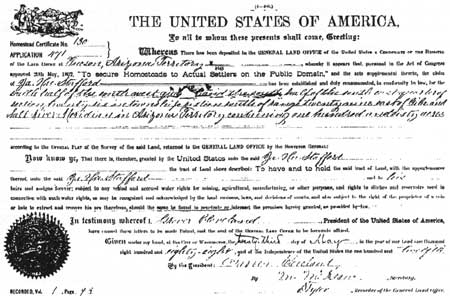

| Figure 3 — Ja Hu Stafford's homestead certificate, May 23, 1888. (WACC) |

A man named Newton, by some accounts a squatter or army deserter, built a cabin in Bonita Canyon at an unknown date before 1885. This cabin, about a quarter mile west of the Stafford cabin and outside of the Stafford homestead, became the officers' quarters at the the cavalry encampment during 1885-1886. Emma Erickson purchased it, by some accounts from Ja Hu Stafford, in 1886. However, no evidence of Stafford's ownership has been found, and nothing is known of Newton except his name and the existence of his cabin.16

16Louis Torres and Mark Baumler, A History of the Buildings and Structures of Faraway Ranch. Historic Structure Report, Historical and Archeological Data Sections. Denver: Branch of Planning, Alaska/Pacific Northwest/Western Team, National Park Service, Denver Service Center, 1984, p. 22-23; Murray, personal communication; Anonymous, "The History of Faraway Ranch," states that Emma Erickson bought the cabin from Stafford.

The earliest nontechnical description of the Stafford homestead appeared in a diary entry dated April 16, 1882, when young Pauline Stafford wrote:

Mrs. Pauline Stafford and J. H. Stafford live in Bownita Canyon Arizona in a log cabin / the wind is blowing very much today / We have to [sic] horse and 18 chickens / the grass is about 1 inch high / April 7 we had a very heavy frost / froze the water up in the wash pan / that was about 2 inches thick.17

17Journal of Ja Hu Stafford, original owned by Rodney Wheeler, copy provided by Dr. Edward Wheeler. The excerpts herein from the journal and family letters retain their original spelling and grammar.

Mrs. Stafford mentioned only two horses and a number of chickens; Stafford must have had no other livestock at this time or his wife probably would have mentioned them. Pauline Stafford wrote to her father in 1883:

Be sure to bring good cows all that you are able to buy . . . for they will bring cash here. I do not think that you can get a good Utah cow here for any less than 80 or 100 dolars. Thier [sic] are scarcely any good cows here at all and none to sell, thier [sic] are several men here who would like to get to buy a cow if they only could get a chance.18

18Pauline Stafford to her father, August 6, 1883, Stafford Family Collection. There is no evidence that Pauline's father visited the Arizona Territory or the Stafford homestead.

Cochise County, in the southeast corner of Arizona Territory, had been formed out of Pima County on February 1, 1881, with the county seat in Tombstone, 97 miles southwest of Bonita Canyon. Ja Hu Stafford traveled there to register to vote in October of 1882, listing his occupation as "rancher".19

191882 Great Register, entry #3059, Cochise County Recorders Office, Bisbee; Murray, personal communication. The county seat was moved to Bisbee in 1929.

|

| Figure 14 — Map of Fort Bowie and area, circa 1886, including Bonita Canyon. Riggs and Fife residences shown. Unintelligble writing near "Bonita Canon." (Arizona Historical Society) |

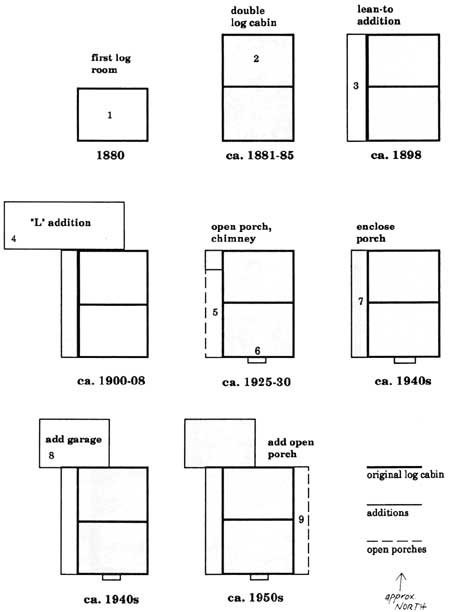

Stafford officially acquired his homestead on April 6, 1886. On the documents filed with the land office Stafford listed improvements such as a double log house, chicken house, smoke house, corral, and a four-acre fenced-in garden. At some time before this date, Stafford had added a second room to the cabin, made of larger logs than the first room. This addition also measured about fourteen feet square. According to family tradition this part of the cabin featured a dirt floor with a stone-curbed well.20

20Entry 471, Tract Book, Arizona, Vol. 166, and individual land record jackets, Washington National Record Center, Suitland, Maryland; Gordon Chappell, National Register of Historic Places--Nomination Form, July 1979, Section 7, page 1. Interview with Helen Kenney by the author, November 14, 1990.

|

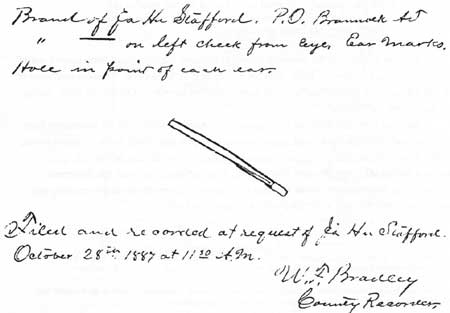

| Figure 5 — Brand of Ja Hu Stafford, 1887. (Brand Book, Cochise County Recorders Office) |

D. THE STAFFORD FARM

Ja Hu Stafford, in middle age, and Pauline, a young teenager, went to work on the homestead to fulfill the terms of the Homestead Act of 1862, which required that the land be used and improved for a period of five years before being granted to the settlers. The threat of Indian attack posed perhaps the greatest concern during these early years; the renegade Geronimo and his band of Chiricahua Apaches hid out in the area after an uprising at the San Carlos Reservation in August, 1881. According to family tradition, Stafford had located the well inside the walls of the cabin for safety. The Staffords found the closest military protection at Fort Bowie, some thirteen miles northeast, and may have taken shelter there at times.21

21Utley, A Clash of Cultures, p. 44; Torres and Baumler, Faraway Ranch, p. 18; interviews with Donald Riggs by the author, May 24, 1990, and Helen Kenney, November 14, 1990; in Forrestine C. Hooker, When Geronimo Rode (a thinly disguised historical novel based on Hooker's experiences with the Cavalry troops at Bonita Canyon in 1885-86), p. 148, residents of a cabin in Bonita Canyon escape to Ft. Bowie every time there was an Indian scare in the canyon.

Stafford's homestead received official approval with a certificate from the President dated May 23, 1888. By this time his activities on the land consisted largely of stock raising and farming. Ja Hu Stafford called himself a "rancher" while registering to vote during his first years in Arizona Territory and his daughter Clara later recalled that in the early days he hauled wood to Willcox where he sold it. By 1888 he had changed his occupation to "gardener," and later to "farmer". Stafford's orchard and garden eventually provided his chief source of income.22

22Faraway Ranch Papers, 1873-1976, Western Archeological and Conservation Center, Tucson; Great Registers at Cochise County Recorders Office, Bisbee; oral history of Clara Stafford Wheeler, Chiricahua NM.

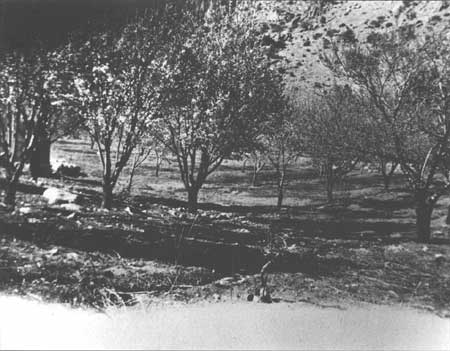

Stafford planted approximately two acres directly to the west and southwest of the cabin with fruit trees such as apples, apricots, peaches, persimmons, and pears. Stafford was, by some accounts, devoted to his orchard although the climate in Bonita Canyon proved less than perfect for fruit trees: early frosts killed a high percentage of the crops every few years. Nevertheless, people came to Bonita Canyon to buy fruits and vegetables from Stafford, whom one recalled as "very much of an orchard man." Remnants of the orchard remain in the field opposite the Stafford Cabin.23

23Homestead patent #130, in Homesteads Vol. 1, p. 93, Bureau of Land Management, Phoenix; copy of the homestead certificate in Faraway Ranch Papers; taped interview with Nora Stafford, Special Collections, University of Arizona, Tucson.

On the eastern portion of the homestead Stafford had a large vegetable garden, called the "upper garden", fed by a spring. The products sold to local ranchers, markets in Willcox and Pearce, the "Buffalo soldiers" during their year at Bonita Canyon (see page 14), and to Fort Bowie. No official documentation has been uncovered concerning the sales to Fort Bowie, but family tradition and a reminiscence of close neighbor Neil Erickson states that Stafford delivered produce to the fort.

Stafford's personal journal reveals sales of produce and eggs to a number of officers from Troops E, H and I, 10th Cavalry, while they were stationed at Bonita Canyon in 1885-86. Stafford documents purchases by Captains Theodore Baldwin and Joseph Kelley, First Lieutenant Millard Eggleston, Quartermaster Sergeant Charles Key, Sergeants James Spears and Charles Turner, and Private Randall Blunt, all stationed at the Bonita Canyon camp. The purchases, mostly for 25 cents to two dollars and sometimes with credit, included eggs, radishes, beans, lettuce, cabbage, onions, pumpkin, potatoes, carrots, tomatoes, parsnips, corn, squash, and watermelon. Apparently the garden was large, of two to four acres, and the only one of its size to be documented in the area other than that of a Mr. Barfoot who grew potatoes in Barfoot Park, in nearby Pinery Canyon.24

24Betty Leavengood, "Faraway Ranch History, Neil and Emma Erickson up to 1903." Typescript, Chiricahua National Monument, 1984, p. 32; oral histories with Ben Erickson, 1970, and Clara Stafford Wheeler, 1971; Journal of Ja Hu Stafford; Tagg, Camp at Bonita Canyon, troop musters on p. 281.

Stafford's garden received water from a nearby spring, by some accounts through a wooden flume. A number of reports have stated that this or another source was a hot spring. According to Stafford's daughter Clara, by diverting the warm water to the garden, vegetables could be grown even in the winter. Family accounts stated that an earthquake, known to be on May 3, 1887, caused the hot water to disappear, leaving Stafford to irrigate with a more conventional method. Stafford wrote of another earthquake on the day it happened, November 5, 1887, but made no mention of the hot spring or any damage: "had quite a heavy Shock of Earthquake this evening and also had our first frost the same night." Daughter Clara stated almost a century after the fact, that "when the earthquake came which they did have one in the 80s it just shook the fireplace all to pieces and threw her [sic] all over the yard and of course big rocks came down off the mountains too . . . the spring there had hot water at that time but after the earthquake came why the hot water disappeared . . . and the spring . . . [they] tried to find it several times but they never did find it."25

25Interview with Kenney; oral history of Clara Stafford Wheeler. Kenney corroborates the hot spring story, and also remembers seeing remains of the wooden flume. As Clara was born in 1892, her description was not first hand and may not be accurate.

Stafford continued gardening on his homestead for at least a decade. In 1896 he laid claim to water to the north of his homestead, filing this notice (in Stafford's unique spelling):

I Hear by Clame All the water on the North West quarter on South West 40 of Section 25 and the North West 40 of the South West quartor ton Ship 16 Range 29 in bunita canyon. I clame the wator to erigate with and for Stock Water I All So

Clame the Rite of way for Erigating ditch over the same Land to my garden.26

26Document signed J.H. Stafford ("my full name Ja Hu Stafford") witnessed by Neil Erickson, recorded June 4, 1896. Cochise County Recorders Office, Bisbee, Arizona.

Pauline Stafford's letters reveal some of the details about the gardens and their products. In September 1892 she wrote, "We have a very nice garden and lots of watermelons and we have about an acre planted to Peanuts they do well here we raised over 8 sacks last year . . . ." Later that year she wrote to her sister: "I must tell you something about what we have been doing. I have made 50 quarts of Ketchup for sale and 6 gallons of Citron Preserves, 3 gallons of Tomatoes Preserves besides I have put up for my own use 2 gal. apples 3 gal. Peaches 3 gal Gooseberries and about 10[?] gal. Tomatoes and then I want to make a lot more Preserves. I also dried about 25 pound Sweet Corn and alot of String Beans."27

27Pauline Stafford to family members, September 5 and October 19, 1892, Stafford Papers.

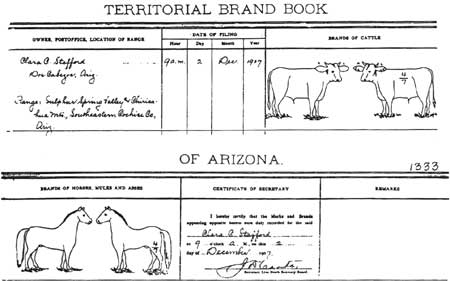

With the abandonment by the U.S. Army of Fort Bowie on October 17, 1894, Stafford no doubt lost a valuable customer. However, Stafford also had cattle to rely on for income. He first registered a brand for cattle and horses on October 28, 1887, and renewed the registration on November 20, 1898. Stafford's brand was a diagonal slash on the left cheek, and holes as earmarks in the points of each ear.28

28Utley, A Clash of Cultures, p. 83; Brand Book 1, p. 323, Cochise County Recorders Office, and Livestock Sanitary Board, Brand Book 1, p. 636, Arizona State Archives. See the drawing of the brand in illustrations at the end of this paper.

|

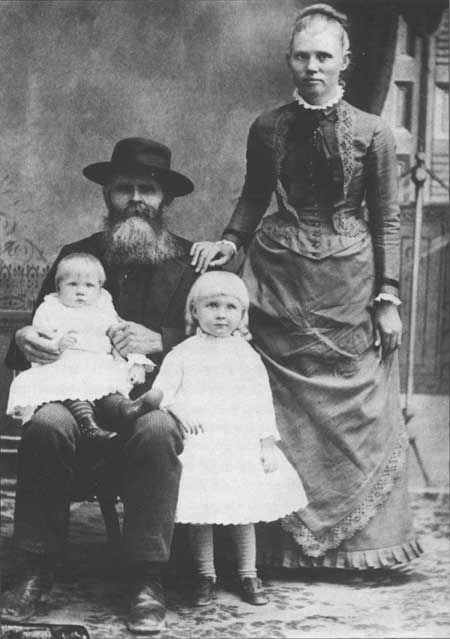

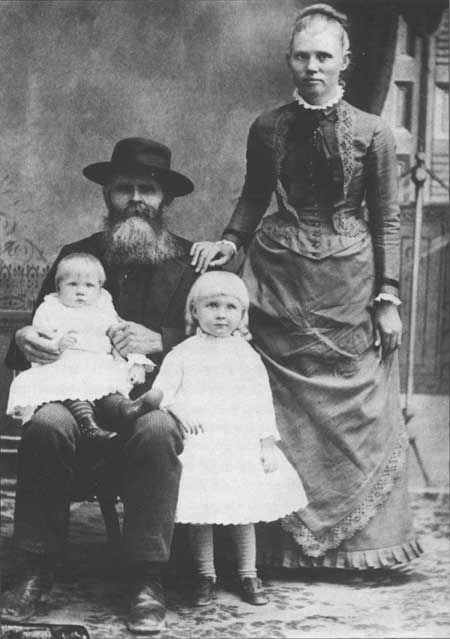

| Figure 6 — Stafford family, 1997: Ja Hu, Pauline, Pansy standing, Anna Mae on lap. Courtesy of Tom Kelly. (CHIR 1756) |

E. HOME LIFE IN BONITA CANYON DURING THE 1880s AND 1890s

Pauline Stafford became pregnant within a few years of settling at Bonita Canyon, but the couple's first child died in childbirth. The parents reportedly named the child Reveley, an old family name; they buried the baby in a small simple grave with a rudely carved "R STAFFORD" on a rough stone, in the south part of the orchard where it remains.29

29Another story has been circulated in which the child was named Reveille because of its birth during reveille at the military camp downstream; this is unlikely as the military camp was not in place until September of 1885, by which time Mary Pansy Stafford had been born.

Ja Hu and Pauline went on to have six children, five living to adulthood: Mary Pansy (called Pansy) born January 15, 1885, Anna Mae born December 1, 1886, Ruby Evelyn born September 30, 1888, Thomas Asa born May 30, 1890, and Clara Clementine born June 10, 1892. Stafford added a room to the cabin, of a slightly larger-diameter logs, between 1881 and 1885, around the time the first baby was due. It appears that the family of seven lived in these small quarters for most of its existence; by the time another addition was constructed near the turn of the century, almost half of the family had left or died.30

30Stafford Papers and personal communication, Wheeler and Murray. Torres and Baumler, Faraway Ranch, p. 64.

One would hope that Pauline had assistance with her many births by a midwife or neighbor lady. Ja Hu Stafford considered himself able to take care of the medical needs of his family, and may have assisted with the births. Years later a neighbor, Neil Erickson, recalled a time in late 1886 (about the time that Anna Mae was born) when he "was summoned to go and get [neighbor Mary Riggs] to perform an act of kindness for my near neighbor Mrs. Pauline Stafford." While the nearby residents lived at widespread locations, they no doubt helped each other as necessary. Erickson wrote to his new wife in 1887 that "Mr. and Mrs. Stafford send their best regards to you and wish you would come out here and live. They say that it's kind of lonesome now with this house [the Erickson cabin] empty."31

31Neil Erickson, "A Tribute to Mary B. Riggs," newspaper and date unknown, and Neil to Emma Erickson, February 23, 1887, Faraway Ranch Papers.

Pauline revealed some of the family's hardship in a letter she wrote to her sister in Utah announcing the birth of second child Anna Mae in December, 1886. "She is doing well but I am not strong enough yet to do much but take care of baby and Pansy. . . . I would liked to have sent you some money but I have been sick so much that Stafford has had to be with me all the time so he has not had any chance to make any . . . ."

Three years later the Staffords continued to struggle to make ends meet, as Pauline wrote in January, 1890:

. . . it seems like it is very hard to get A nough money to buy our own nessecaries / it was a very dry Summer last Summer and the Cattle men did not have any fat beef Cattle to sell so they have not got any money and they are the pepol that we get most of our money from / Some of the Cattle men are deep in debt to the Merchants . . . .

Nevertheless, the children received gifts during the Christmas of 1889:

[Pansy] got for Christmas a kitchen and doll and four handkerchiefs. May got a running turtle a doll and four handkerchiefs the baby got two dolls and a pretty little blue Sacque, and I got six glass sauce plates one scarf for a chair and a silver sugar spoon. Stafford got a Mustache cup and two linen towels. It will be Pansy's birthday on the 15 and I have to make a dress for her before then for a present and I am going to have a dinner party for her.32

32Pauline Stafford to Clara Madsen, December 21, 1886 and January 5, 1890, Stafford Papers.

Life at Bonita Canyon in the 1880s brought excitement and danger at times. Until 1886 Indians remained a potential threat to the settlers. A family story relates how Pauline shot at a Black soldier who approached the cabin, perhaps thinking he was an Indian; the only casualty was one of Stafford's prize fruit trees which the bullet severed. Wild animals lurked about the homestead, chasing the kids and injuring the livestock. Pauline wrote in 1886 how "a Panther caught Nellies 4 months and a half old colt about 200 yards from the house and Stafford shot and killed it / it measured 6 feet 8 inches from the end of his nose to the end of his tail / it measured 30 inches around the girth / 8 inches around the fore leg / the Panther was a male." Bobcats entered the house on at least two occasions only to be dispatched by Ja Hu Stafford with a knife. Stafford wrote in his journal of killing a bear on October 6, 1887.33

33Pauline Stafford to family, August 19, 1886, Stafford Papers; Journal of Ja Hu Stafford.

After about five years on the homestead the isolation decreased. In the Fall of 1885 a detachment from the Tenth Cavalry composed of Black enlistees, known to some Indians as "Buffalo Soldiers", camped in Bonita Canyon about a quarter mile west from the Staffords.

In October of that year Troop H, under the command of Capt. Charles L. Cooper, established a semi-permanent camp at Bonita Canyon. The troop was given this mission: to guard the water source; to prevent Apache renegades from escaping to Mexico through the canyon; to act as couriers for the southern mail service out of Fort Bowie; and to protect the local ranchers from Indian attack. Later joined by Troop E, the original detachment to have camped there, the ranks grew to almost 100 men and a similar number of horses. These numbers diminished in April 1886 when Troop I, with a strength of about 50 men, relieved Troops E and H. After a year of uneventful duty at Bonita Canyon, the soldiers abandoned the camp on September 15, 1886; Geronimo had surrendered and the Arizona Indian Wars had ended.34

34Mark F. Baumler "The Tenth Cavalry and the Camp at Bonita Canon, Arizona Territory," chapter in Tagg, The Camp at Bonita Canon, pp. 37-44.

Undoubtedly the proximity of the military camp had a significant impact on the Staffords' daily life. Apart from the supposed shooting incident at the cabin, Ja Hu Stafford reportedly sold produce to the encampment. His daughter Clara recalled that Ja Hu "sold vegetables to the Negro soldiers who were camped . . . right across Newton Creek there from [what later became] Faraway [Ranch] . . . ."35

35Ibid., p. 52; oral history of Clara Stafford Wheeler.

Four years after the 10th Cavalry left, Bonita Canyon experienced an Indian scare when "Big Foot" Massai, a Chiricahua Apache who had escaped from a train deporting Chiricahuas to Florida in 1886, appeared up the canyon accompanied by his pregnant wife. Neil Erickson, the Staffords' neighbor from 1888 to 1918, wrote an account of the story in his memoirs many years later:

The first we heard of Massai after he escaped from the train was in the early part of May 1890. Mr. J. Hue Stafford and family, wife and two children, and a young girl, Mary Fife, myself and family, wife and one child, and my brother John, were the only residents in Bonita Canyon about twelve miles south of Ft. Bowie, then garrisoned with two troops of Cavalry and one Company of Infantry.

This bright and early May morning Mr. Stafford was going to the fort with vegetables for officers and soldiers stationed there. He had his horses in a small enclosure about three-quarters of a mile above the house up in the canyon. He was on his way there to get the horses when he spied in a sandy place in the road a moccasin track. He stopped for a moment to consider and then returned home to protect his wife and children . . . .

On arriving home he sent Mary Fife down to my house a quarter of a mile to warn me. She came like a whirlwind, skirts a flying, and said, "The Indians are coming down the canyon."

About this time Mrs. Stafford with her two children, Pansy and Anna May, came down to my house . . . .

Stafford found that one of his horses had been stolen from his pasture; Massai was pursued but apparently escaped to Mexico after safely depositing his pregnant wife at the San Carlos Reservation to the north. Stafford's horse was eventually found and returned later that year. In one of Erickson's accounts (Erickson's story appeared in numerous versions in the press) he described Mary Fife as an employee of the Staffords; in another account, a Mrs. Fife served as a nearby midwife. Mrs. Fife may have been the mother of Mary, a young unmarried girl.36

36Leavengood, "Faraway Ranch History;" autobiographical letter reminiscence by Emma Erickson, January 10, 1946, p. 65, Chiricahua National Monument; Murray, personal communication.

Civilization crept closer to Bonita Canyon in August of 1887 when the government established Brannock post office on the Riggs Home Ranch at the forks of Pinery and Bonita Creeks. Brannick Riggs, the pioneer neighbor of the Staffords, became the first appointed postmaster (the postal office inadvertently misspelled the name as "Brannock"). Until 1887 the Staffords had traveled to Dos Cabezos, some 20 miles away, for mail. Brannick and Mary Riggs established a private school at their ranch, which circa 1886 became part of a new El Dorado School District #16. Within a few years the district constructed a schoolhouse closer, to Bonita Canyon, where all of the Stafford children attended school.37

37Barnes, Arizona Place Names, p. 61; Murray, personal communication. The name Dos Cabezos changed to the currently used Dos Cabezas in 1948 (Arizona Republican, November 6, 1948).

The permanent settlement of Neil and Emma Erickson in the summer of 1888 gave a new dimension to pioneer life in Bonita Canyon. The Ericksons claimed the next homestead to the west in 1886 and moved into a three-room house only a quarter-mile walk from the Staffords' cabin in 1888. The Ericksons brought with them a baby girl, Lillian, and during the first half of the 1890s they had two more children at Bonita Canyon, providing playmates for the Stafford youngsters. Erickson, a Swedish immigrant carpenter, had been a U.S. Army cavalry trooper stationed at Fort Craig, New Mexico Territory, when he met Emma in 1883. After his discharge they married and filed for the Bonita Canyon homestead, which Neil visited sporadically to work on the land and existing dwelling, the one reportedly built by Newton and later used by Captain Charles L. Cooper and his family as a dwelling during the "Buffalo Soldier" days. The couple and their daughter Lillian, born at Fort Bowie on February 9, 1888, moved to Bonita Canyon permanently in the summer of 1888.

|

| Figure 7.—In wash with "old man Stafford and kids" (noted by Neil Erickson), circa 1900. (WACC 86-16-0255) |

That Christmas the Ericksons brought a new life to the little valley. Emma Erickson later wrote:

None of the neighbors at that time had seen a Xmas tree. I decorated a nice Xmas tree for the Stafford family . . . [they] thought it was wonderful. And I had appropriate gifts for all the family and I invited as many of the neighbors as our little house would hold to come and celebrate Xmas with us.38

38Autobiographical letter reminiscence by Emma Erickson, pp. 60-61, January 10, 1946, Chiricahua National Monument.

After that Emma had yearly Christmas parties, which got so large that they eventually had to be held at the El Dorado schoolhouse. She distributed gifts to families all over the area. Emma also reportedly taught the neighbor women to preserve fruits and vegetables.39

39Leavengood, "Faraway Ranch History," p. 32.

Pauline Stafford's letters to her sister Clara in Utah provided a vivid look into the home life in the cabin during the 1880s and 1890s. The family was poor, having a double burden of many children and limited opportunities for income. For some time Pauline had her sister Clara buy shoes in Utah for the family for two dollars a pair; in one letter she asked her sister to buy an extra pair for "little Thomas, as the ones he is wearing are looking rather shabby and will not last long"; she asked Clara to loan the two dollars as a favor because "Mr. Stafford" would only let her send "2 dollars, all the money we could spare at present."40

40Pauline Stafford to Clara Madsen, March 12, 1894, Stafford Papers.

Nevertheless the children received some presents, as Pauline wrote in thanks to Clara, adding a slice of home life in Bonita Canyon in 1894:

The Children were very aggreable Supprised to get the Valentines and Handkercheifs you sent them they were just simply delighted Even the baby was Pleased / She has not been very well for several days taken Cold in her eyes they were so Painful yesterday that she could scarcely see out of them Swelled almost Shut but to day they were very much better / Clara is a great Papas Baby She sleeps in Papas arms all night and crys if I want to take her. She speaks a good many words and she says them very Plain She calls Thomas Boy all the time this morning when Pansy and May started to school she went to the door and called, Bye Children. I told her Aunt Clara was going to send her a Pair of Shoes and then she looked down at her shoes and laughed. . . . I want to put Thomas in pants the 30 day of May that is his birthday he will be 4 years old then . . . .

In an earlier letter, dated September 5, 1892, Pauline writes of some dissatisfaction in the rough life at the homestead:

Mr. Stafford has been thinking of selling out and going back to North Carolina his old home where he was born he has a place their that was left to him and his brother by his father. If he could have sold outlast Spring he would have gone to Old Mexico but I am glad that he did not for the United States is good enough for me. It has been a very dry Summer here and thier is a great scarcity of grass and water for the cattel on the plains and valleys.41

41Pauline Stafford to Clara Madsen, February 21 [?], 1894 and September 5, 1892, Stafford Papers.

Nevertheless, Stafford and his family stayed on at Bonita Canyon for another 25 years.

F. JA HU STAFFORD AS A WIDOWER

The year 1894 found Pauline pregnant for the seventh time. In a letter from Pauline to sister Clara, dated July 22, arrangements are being made for "Aunt Clara" to come to Bonita Canyon, a visit that Pauline desperately needed:

I expext to be sick by the end of August or at least by the [?] of Sept so you will see the nesecesity of starting by that time if you do not come I do not know how I will get along as it is just impossible to get help here at the present time thier is only one woman that I know of that I can get at all and she has two small children.

Evidently sister Clara did not arrive; Pauline died in childbirth on August 26. Ja Hu buried her in the community cemetery near the mouth of Bonita Canyon. The baby survived for what may have been many months, under the care or neglect of his father.42

42Pauline Stafford to Clara Madsen, August 22, 1894, Stafford Papers.

Family stories abound about the circumstances surrounding the unnamed baby's life and death. Stafford's granddaughter Naomi Moore related this popular version in an oral history:

It died of pneumonia because grandfather insisted on trying to take care of it himself and he had to take care of the orchard and the garden . . . . Mrs . Erickson tried to get him to let her have the baby for awhile because she had milk for it and grandfather didn't and he was going to raise the baby himself. Well the baby died from pneumonia because grandfather had left the baby and he had built up a big fire in the stove but then I guess he was gone quite a bit longer than he intended to be and when he came back the baby was very cold and the fire was out and this is how the baby got pneumonia and died . . . . I don't know if he even named the baby . . . .43

43Taped interview with Naomi Moore by Betty Leavengood, August 4, 1987, Stafford Papers.

Stafford's daughter Clara provided her interpretation of the incident:

He thought because he had been through the army and as a nurse in the army in the hospital that he knew as much about [it as] a doctor did about any sickness and we never had a doctor in our house when . . . we were little.

Stafford's granddaughter Helen Kenney related that Mrs. Barfoot from a nearby ranch took the baby for a while until Stafford took him back.44

44Oral history of Clara Stafford Wheeler; interview with Kenney.

Stafford found himself a widower with five children. Pansy, the oldest, left to work as a housekeeper in Willcox soon after her mother's death; later she went to school and worked in Bisbee, where she met her future husband. The other children helped as much as they could. Perhaps of the greatest help was their close neighbor, Emma Erickson, who had three of her own children. A Stafford family member described the situation:

[Stafford] raised them by himself. Of course I say by himself, but I think Mother Erickson, if it wasn't for her he may not have been able to raise them because she lived just a stone's throw from the cabin, you know, and her three children were about the same age as [Stafford's] children. Of course they played together all the time and I think they were at Mrs. Erickson's as much as they were at home . . . .45

45Taped interview with Moore.

Stafford's daughter Clara, who was only two when her mother died, recalled:

Mrs. Erickson . . . was such a wonderful woman to us, she was just like a mother and told us if we got scared or needed anything come down there so whenever it lightening . . . we were scared to death and we ran out with the lightening . . ..

The Stafford children, even the later grandchildren, referred to her as Mother Erickson, or Grandmother Erickson.

The Stafford children also contributed a great deal to the survival of the family. According to Clara, "Mother was always quite a good dressmaker. She sewed and everything for us and when Mother died . . . Anna Mae was only about 8-9 years old . . . and she took up sewing right away and she sewed for us because there were . . . 3 little girls . . . . Poppa didn't have enough for all of us anyhow and [Pansy] ran into Willcox and got her . . . a housekeeping job as a maid . . . . She come home every so often and bring us some little thing and made us . . . so happy."

Stafford kept the farm operating yet still watched the children and taught them the ways of pioneer life as he knew them. Clara later told how "Poppa was really a wonderful person. He took care of us when we were little, [and] he taught me how to shoot when I was 5 years old . . . we lived so much on wildlife, on wild things like squirrels and rabbits, better than things we could get in the line of meat . . . "46

46Oral history of Clara Stafford Wheeler.

While Stafford is remembered fondly by his daughter, she told of his difficult side as well:

Poppa made awful bread . . . it was old yellow bread and I will never forget it . . . if we got out of anything he wouldn't let us borrow anything. People borrowed from us all the time. One day he was making this sourdough bread like the miners baked and he had put a cloth above it over it to keep it warm and when he came back in Tommy's little kitten was asleep on top of the dough and he was so mad he took the little kitten out and killed it and when Tommy and I came home why we wouldn't eat any supper and Poppa told us that we had to eat and we couldn't eat . . .

I had a little pet squirrel and we all loved it and the neighbors around did too and people that came to buy fruit there they loved the little squirrel and when winter came he was storing up things fast and he carried off apples . . . so many that Poppa had saved for us to eat in winter time and so Poppa killed him and had him all fried nice and brown when we came home from school one day . . . we wouldn't eat a bite of that squirrel and he didn't either.47

47Ibid.

|

| Figure 8 — "Stafford Cabin in early days, Mr. Staffor (sic) on top - shingling" (noted by Neil Erickson), circa 1898. This is the lean-to addition; note salvaged lumber in foreground. (WACC) |

Stafford ordered a mail order bride and was married on August 23, 1898 in Tombstone. In his excitement he reportedly had his hair and beard dyed to hide their whiteness. The new bride, Carrie Goddard of Missouri, found herself faced with a sixty-two year-old widower with four or five children, all living in a two-room log cabin on the edge of a desert wasteland; she soon returned alone to her home state.48

48Ibid.; notes on marriage from Col. Tom Kelly. A number of humorous stories have circulated about Ja Hu's hair dyeing episode; reports of the resulting color range from red to black to purple. One story, told by Lillian Riggs and related by Richard Y. Murray, says that a Willcox barber, as a practical joke, dyed Stafford's hair and beard green just before he was to meet his bride at the railroad station.

Late in the century Stafford made a major improvement on the cabin. In a photograph dating from about 1898, Stafford stood on the roof of a shed or lean-to addition on the west side of the cabin, apparently nailing shakes, while four of the children (Pansy was absent) stood behind a large pile of lumber. The addition was of vertical board and batten, with a window on the south side and a door on the west side visible in the photograph. The addition appeared to be almost completed, yet a large pile of lumber remains. Possibly Stafford used the lumber to construct a larger addition to the cabin a few years later. Stafford may have purchased the lumber from the Riggs sawmill in Pinery (or Pine) Canyon, or salvaged the lumber from Fort Bowie, which had been abandoned in 1894. A number of nearby residents obtained construction materials from the vacated buildings at the fort. These materials could have been used to build the third addition, or "ell", on the cabin some years later. This addition, the last made while the Staffords owned the homestead, was a rectangular frame room with board-and-batten sides. Placed on the north end of the cabin, it gave the home an "L" shape and appears to have almost doubled the size of the dwelling. It is estimated that Stafford constructed this last addition about 1900, when he was still in good health and four children remained at home.49

49Utley, A Clash of Cultures, p. 83; Torres and Baumler, Faraway Ranch, p. 66; Murray, personal communication.

In 1898 and 1899, Neil Erickson wrote in his diaries of planting beans and sweet corn in Stafford's field; either Stafford no longer used the gardens or Erickson helped Stafford with the work at times, or the two shared the field. Also, Erickson noted the presence of a flume on the other side of the creek; where this flume was located or whether this supplied Stafford's land is unknown.50

50Neil Erickson diaries, March 28-29, 1898, August 1899, copies at Chiricahua National Monument, made from Faraway Ranch Papers.

Bonita Canyon residents traveled to Dos Cabezas, Willcox, and other Cochise County towns for postal services (the Brannick post office had a short life) and/or merchandise. After the smelter town of Douglas was platted in the southeast corner of the Arizona Territory in 1901, much of Bonita Canyon's commerce shifted there, although slowly. The El Paso and Southwestern Railroad passed through Douglas, and the Bonita Canyon families appeared to have traveled more often to the new town by the 1920s.51

51Arizona Republican, February 12, 1901, p. 3; Meinzer and Kelton, Geology and Water Resources, p. 15. By 1900 the Brannick Post Office was obsolete.

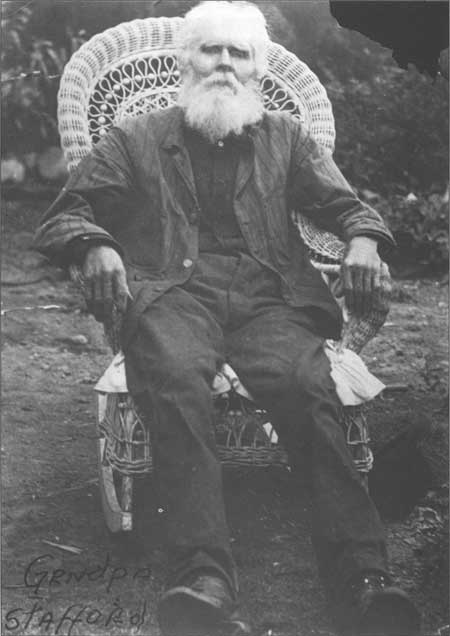

G. LAST YEARS OF THE STAFFORD FAMILY AT BONITA CANYON

Ja Hu Stafford reached the age of sixty-six at the turn of the century. Tax and voter records of Cochise County indicate some gaps in Stafford's activities after that; for instance, he did not register to vote in either 1906 or 1908, after years of faithful registration. In 1910, because of failing health, Stafford gave his daughter Clara control of the ranch. The older girls had left home by then and Stafford's only son, Tom, went to Illinois for a year in 1911 to work in a cousin's apple orchard, and again in 1914.52

52From voter records at Cochise County Courthouse, tax records at Arizona State Archives, and Stafford family notes. Pansy Stafford married Francis R. Bree and died in childbirth at midnight on January 26, 1913 in Dos Cabezas; Anna Mae married Thomas Jefferson Riggs and died in 1963; Ruby married Jess Amalong and died in 1979; Tom married Nora Swanner and died in 1966. Descendants of these unions reside in Arizona and other parts of the country.

|

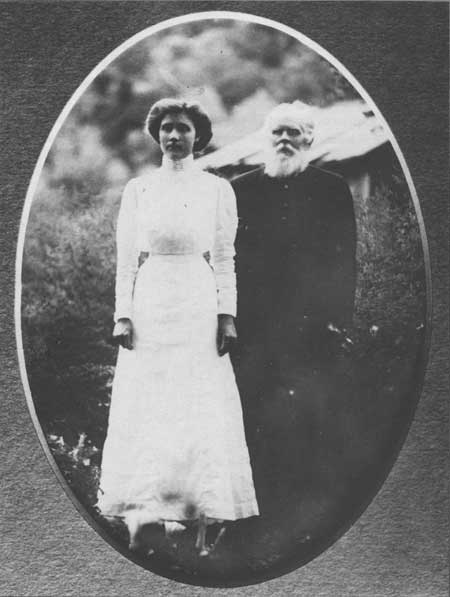

| Figure 9 — Ja Hu Stafford and daughter Clara, circa 1911. "L" addition behind Ja Hu, lean-to behind Clara. (CHIR 1550) |

|

| Figure 10 — Bonita Canyon group including Anna Mae Stafford, who married T. J. Riggs in the Stafford cabin in 1903 (sitting at right); Pansy Stafford, who married Frank R. Bree in 1903 (on ground) and Lillian Erickson and Ed Riggs' (bench, left), circa 1902. (WACC 86:16:0321) |

Clara Stafford, youngest daughter of Ja Hu and Pauline, had been attending Tempe Normal School, but she gave up her education in 1910 and returned to Bonita Canyon to help her aged father. A few years earlier, at age 15, she had registered brands for cattle and horses in her name. Her brand, a four over a seven ( ) in addition to earmarks, became the Stafford ranch brand. The Stafford livestock grazed in the canyon, on public range in the Sulphur Spring Valley and, as they had since about 1894, in the lands above the ranch in the Chiricahua National Forest. Their neighbor, Neil Erickson, acted as forest ranger for the west district of the Chiricahua National Forest, this district containing the area adjacent to and including much of Bonita Canyon; the ranger station stood just over the fence from the Staffords' orchard.53

53Stafford Papers; Livestock Sanitary Board, Brand Book 3, page 1333, Arizona State Archives; correspondence and clippings in Faraway Ranch Papers.

In early March, 1911, Forest Supervisor Arthur H. Zachau wrote to Erickson from headquarters in Portal, Arizona:

In looking over the grazing applications received from you I find that none is included for Mr. Stafford's stock. In view of the fact that cattle owned by him or members of his family has been using range jointly with yours, I do not quite understand why he should not also apply for a permit.

Mr. Campbell brought the matter to my attention some years ago; but since Mr. Stafford is running his stock under your very eyes I assumed that if any of his cattle were on the Forest you would see to it that he took out a permit . . . .54

54Forest Supervisor to Neil Erickson, March 2, 1911, Faraway Ranch Papers, Series 8, Box 21.

Within two weeks Clara submitted an application for a grazing permit for ten head of cattle and five horses, for the period of March 16, 1911 to March 15, 1912, in the area of Bonita Canyon, Newton Creek, and head of Picket Canyon to the north of the Stafford homestead. She declared that the Staffords had two acres of improved farm land on the "home ranch" and 150 acres of summer and winter grazing land, and owned a total of sixteen head of cattle and eight horses, ranged during the winter "on my homestead and Forest lands adjacent thereto and on public range in Sulphur Spring Valley." She also declared that the Staffords had regularly used range in the Chiricahua National Forest during the past nineteen years, although not last season. In June, 1911, Clara paid a grazing fee of $5.50 for 24 head of livestock that "will be grazed on the range located 5/8 within the National Forest." Clara had Picket and Little Picket Canyons fenced with wire strand stapled to trees in early 1913 to accommodate provisions of the permit.55

55Faraway Ranch Papers, Series 8, Box 21.

|

| Figure 11 — Clara and Ja Hu Stafford, circa 1913. Tom Kely Collection. |

The number of Clara's livestock fluctuated over the next few years, according to her lease records. Her herd increased to 30 head of cattle and 10 horses in 1912, then up to 35 cattle by 1915; the improved land at the farm increased in acreage from two acres in 1911 to three acres in 1912, up to ten acres in 1915. By this time Tom Stafford had returned to the ranch with his new wife Nora, and may have been responsible for the sudden growth of the farm and ranch; Tom took responsibility for the permit applications, although they were still held in Clara's name. Nora Stafford later recalled the large orchard at the homestead, with pears, plums, peaches and "the best apples you ever ate in your life." Tom and Nora Stafford lived in the log cabin for almost a year and a half, from the time of Clara's marriage in August of 1914, until moving to their own homestead near Pearce, Arizona, at the first of the year, 1916.56

56Grazing records in Faraway Ranch Papers, Series 8, Box 21; oral history of Nora Swanner Stafford.

Meanwhile, Ja Hu Stafford died at age 79 on Friday, November 14, 1913, apparently of natural causes. The obituary in the valley's newspaper referred to Stafford as "a well known pioneer of the Chiricahuas." The family buried Stafford in the community cemetery near the mouth of Bonita Canyon, next to his wife, Pauline.57

57Arizona Range News, November 21, 1913. There remains confusion over Stafford's age.

Clara, who had married Wilber B. Wheeler, the Methodist minister who had presided at her father's funeral, acted as executrix of the estate. The Wheelers lived in Cochise, Duncan and Cashion, Arizona after their marriage on August 5, 1914. Except for five dollars left to Stafford's three grandchildren from his previous marriage, the estate went to Clara, who had taken care of her father in his old age. The inheritance consisted of $165 in cash, $826 in personal property, and real estate (the homestead) valued at $1,144,00.58

58Probate closed February 3, 1915. Probate Orders, Book 3, pp. 10-11, Cochise County Recorders Office; notes in Stafford Family Collection.

|

| Figure 12 — Ja Hu Stafford in old age. Rose Bree Collection |

Supposedly because of a dry winter and poor grazing conditions, Clara Stafford Wheeler sold about half of her cattle in October of 1915 to George Henshaw of Cochise, then filed a waiver of grazing privileges. Wilber Wheeler apparently had a dispute with the Forest Supervisor about whether his wife should pay grazing fees since the cows had been sold. This blew up into charges and counter-charges in letters between Wheeler and Supervisor Arthur Zachau that drew neighbor Ranger Neil Erickson into the fray.59

59The grazing and land dispute is documented in letters, although unfortunately Mr. Wheeler's original letter of complaint is not available. Acting District Supervisor Kavanagh to Forest Supervisor Zachau, January 20, 1916; Zachau to West District Ranger Erickson, January 25, 1916; Zachau to Kavanagh, January 25, 1916; Erickson to Zachau, February 7[?], 1916; Faraway Ranch Papers, Series 8, Box 51.

In a letter to the District Forester in Albuquerque, Zachau outlined Wheeler's complaints:

Mr. Wheeler's letter is not very clear in as much as he does not state what he really wants except that he asks for proper protection for his wife's grass and water supply. His specific charges which you wish answered, as near as I can determine, are as follows:

1. That the lessee of his wife's ranch, without her permission, made use of her grazing privileges.

2. That last year the lessee could not run the stock on the range it occupied heretofore because the range was over stocked.

3. That further grazing privileges are not desired because the running of stock in that vicinity will not only damage the Forest but himself and his wife as well as for the reason that the overstocking has been so serious as to impair the water supply.

4. That Ranger Erickson is anxious to obtain the grazing privileges and ranch property of his wife and is willing to see the range and water supply destroyed to make her sell out.60

60Zachau to District Forester, January 25, 1916.

Both Zachau and Erickson countered the charges in separate letters. Zachau noted that the "lessee" was Clara's brother Tom, to whom she had turned over the ranch after her marriage to Wheeler, and that Tom "was in complete charge of the place and was recognized by Ranger Erickson and myself [Zachau] as her representative so far as dealings with the Forest are concerned." Zachau was puzzled by the charge that the "lessee" was using grazing privileges without permission, since the "lessee" was Tom Stafford and the cattle belonged to Clara. He also disputed the claims that the allotment was overgrazed and that the water supply, from Bonita Creek, was impaired; in fact, it had been a dry winter and "if Mr. Wheeler's water supply was lower last year than usual, it must be attributed to an Act of Providence. The very same thing happened in a good many other localities on and near the Forest."61

61Ibid.

|

| Figure 13 — Brands registered to Clara Stafford, 1907. (Arizona State Archives) |

Of the greatest controversy was the charge that the Ericksons coveted the Stafford homestead. The Acting District Forester, E. N. Kavanagh, also appeared to be alarmed at the possibility that Forest Ranger Erickson or members of his family wanted to use Forest lands for grazing, a practice that is "frowned upon throughout the Service."62

62Kavanagh to Forest Supervisor, January 20, 1916.

Zachau responded that Wheeler's claims were unfounded, and that because of the Ericksons' recent major improvements to their house they could not afford to purchase the Stafford homestead. Also, the Ericksons had transferred their "few" cattle to their son Ben.63 Neil Erickson responded to Wheeler's charges in a letter that provides an interesting, although one-sided, history of the dispute, and some insight into later developments:

In regard to statement No. 4 that I am anxious to obtain the ranch property of Mrs. Wheeler's, and the grazing privilege annext thereto, would be alright if I could see my way clear to obtain it in a righteous and legal manner, which at the present time I cannot even think of doing, and for the reason you stated in your answer to the Forester. I have exhausted what little money I had, and borrowed more from the Bank of Willcox, to complete the house with that I am now living in on my own homestead.

It's true that on or about the 2nd of October when it had become known that Mr. Wheeler had sold his wife's cattle, and offered the ranch property for sale, my daughter Lillian, went to Cochise where Wheeler and his wife was living at that time, and made them an offer for the place, for herself (not for me), but failed to come anywhere near [what] they asked for it at that time, since that none of us have mentioned buying to anyone. And as to my willingness to destroy the range and water supply on or pertaining to the Stafford ranch, I fail to see how I could if I were ever so willing, as her property is located above that of mine, and no other stock but those of Mrs. Wheeler had access to the range above her place either on the north, East, or South.

About the 28th or 29th of Sept. Mr. Wheeler came up here to take out the cattle, I asked him if he intended to renew his application for permit for the next season, if not, Ben Erickson would probably like to apply to graze Mrs. Wheeler's allotment. He said "no he would not want it" but wanted to retain the privilege for probably future use, I explained to him that he could not very well hold the range without making use of it, and that according to our Reg. they would not be debarred the use of the range adjoining his wife's homestead whenever she was ready to occupy the same. And owing to the fact that the range is closely grazed and the Stafford homestead not fenced, and surrounded on three sides by Forest range, it would only be a source of annoyance from Mr. W. B. Wheeler. I have been told by the reverend's relatives on his wife's side, that he sold the cattle to pay for his education to the ministry, rather that from shortage of range, the truth of this I cannot vouch for.

Mrs. Clara S. Wheeler has now on and around her homestead seven or eight head of horses; they are range stock. I am anxious to know what we can do with them, they are on Forest range most of the time and a permit should be issued for them, but since Mr. Wheeler is not willing to pay the fee due on cattle for the season from 1915-1916, it is hardly to be expected that he will pay on a bunch of worthless horses.64

63Zachau to District Forester, January 25, 1916.

64Letter from Forest Ranger Neil Erickson to Forest Supervisor Arthur H. Zachau, February 7[?], 1916, Faraway Ranch Papers, Series 8, Box 21. According to Wilber Wheeler's son Dr. Edward Wheeler, the intimation that Wheeler sold the cattle to pay for his education is probably correct; Wheeler, from a "very poor ranching family" in Texas, had completed five to six years of training for the ministry in Georgetown, Texas and Nashville, Tennessee in 1912, and was likely in debt.

|

| Figure 14 — U.S.G.S. map (detail), San Simon quadrangle, surveyed 1914-1915, published 1917. Shows Ericksons house and Stafford Cabin (near the "B" in Bonita Canyon). (WACC) |

To further confuse the issue, one document stated that Clara Stafford shared her grazing allotment with Lillian Erickson. Apparently the Ericksons had indeed been grazing in the Forest lands. Whether there was any resolution to the charges is not known. Meanwhile, in February of 1916, Clara applied for another grazing lease for twenty head of cattle, presumably a new herd, or at least the remainder of her previous one.

Erickson revealed in his letter that his daughter Lillian had an interest in purchasing the Stafford homestead as early as 1915. Lillian, working as a schoolteacher in Bowie, had the reputation of being aggressive and energetic, a forward-thinking and perhaps somewhat liberated young woman.

On April 22, 1918, Lillian Erickson purchased the 160-acre Stafford homestead from Wilber B. Wheeler and Clara Stafford Wheeler for $5,000. The parties arranged terms of $800 down, with yearly payments of $400 the first year, $500 the next, then two payments of $1650; when $2500 had been paid, the Wheelers would deliver the deed and take back a mortgage for the unpaid balance. Miss Erickson made the down payment and the first installment, but could not raise the money for the next four payments, although she apparently paid the interest. By this time the Wheelers had moved to Texas, and after the payments fell into arrears the parties renegotiated the transaction in February of 1923 for $4,000; the terms were paid off by June 15, 1928.65

65Deeds recorded at Cochise County Recorders Office, Bisbee. Faraway Ranch Papers, Series 15, Box 38. According to Murray, Clara shared the proceeds of the sale with all but one (who refused a share) of the surviving Stafford children.

The sale to Lillian Erickson brought to a close the Stafford era at the cabin and the demise of the homestead, and marked the beginning of many significant physical changes to the Stafford cabin itself.

|

| Figure 15 — Sunday School class at El Dorado School, circa 1910. At left, Ja Hu, Clara, Ruby Stafford. Rose Bree Collection. |

|

| Figure 16 — Erickson ranch (distant), Stafford Cabin (below), Neil Erickson on rick, circa 1900. (WACC 86:16:0856) |

|

| Figure 17 — Closeup of fig. 16. Note irrigation ditch, cabin as it appeared before "L" addition. |

|

| Figure 18 — "Old family orchard and chick sales" (notes Erickson) is probably Erickson's orchard, similar to Stafford's. (WACC album 86:16:0528). |

H. STAFFORD CABIN AND HOMESTEAD AS PART OF FARAWAY RANCH, 1918-6866

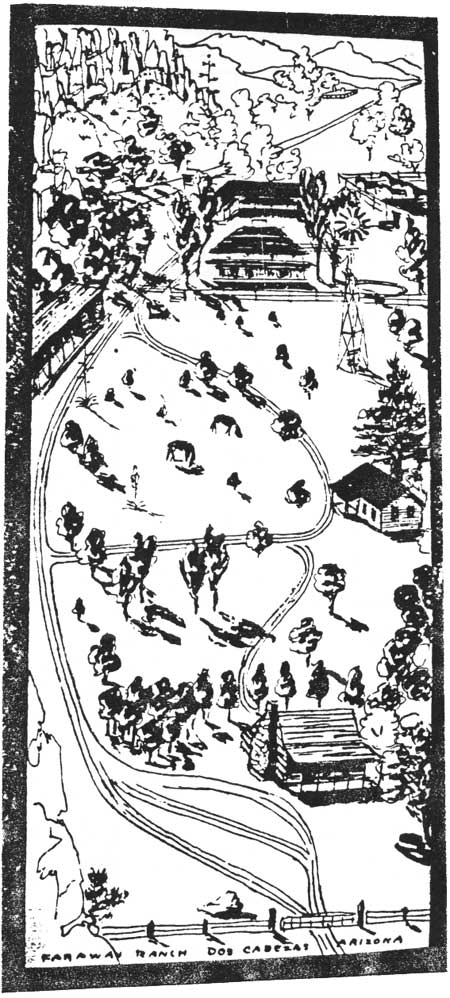

According to family reminiscences, Lillian Erickson purchased the Stafford homestead in partnership with her younger sister, Hildegard, although the deeds name only Lillian. Lillian herself wrote that "Hildegard and I decided to buy the Stafford place." They had an agreement that if one of them married or moved away the other would take over payments and eventual ownership. According to family letters, they paid for the land with Lillian's teaching wages, a bank loan, profits from early guests, and probably income from their cattle. Even before the purchase the two young women had developed an idea of operating a guest ranch in Bonita Canyon.67

66For more history of Faraway Ranch in general, please refer to Torres and Baumler's A History of the Buildings and Structures of Faraway Ranch, 1984.

67Hildegard also spelled her name Hildegarde.

Lillian and Hildegard's parents left the area for ten years when Neil Erickson was transferred to Cochise Stronghold in 1917 to act as District Ranger of the Dragoon and Whetstone Mountain areas; he was eventually assigned to Walnut Canyon National Monument near Flagstaff. The sisters considered their options at the ranch. Lillian had the highest interest in horses and cattle, and Hildegard had been inviting her young friends for weekend stays at the ranch. In 1917 Hildegard had an idea to invite paying guests. After experimenting with short stays from people in the surrounding area her confidence increased. Soon she began hosting visitors for a week or more, feeding them and offering horseback trips into the Chiricahua Mountains and its "Wonderland of Rocks." Eventually Lillian retired from teaching and joined the operation, which soon developed into a modestly busy guest ranch business.68

68Torres and Baumler, Faraway Ranch, p. 49, 50; Lillian Riggs to Neil Erickson, November 23, 1930, Faraway Ranch Papers.

In her own words Hildegard described the embryonic stage of the guest ranch:

After that there were crowds nearly every weekend so in Dad's defence and much against Lillian's wishes I started the boarder business. When our business was a proven success in the fall of 1917 Lillian gave up teaching and came home to assume managership and we together went in to buy the Stafford place.69

69Hildegard Hutchison, ms., no date, Faraway Ranch Papers. According to Murray, Lillian Erickson taught in Bowie through the 1917-1918 school year. Faraway also remained a working cattle ranch.

The guest ranch operations revolved around the Ericksons' large house, a two-story adobe brick structure that had evolved from a small pioneer cabin on the Ericksons' circa 1888 homestead claim. Lillian and Hildegard named it Faraway Ranch, reportedly an idea of Lillian's, who said it was "so god-awful far away from everything." The name was not new to the area, though; a map drawn by Neil Erickson an March 5, 1915, names a "Faraway Point" nearby. Later accounts state that Neil Erickson did not like having the name applied to his ranch.70

70Torres and Baumler, Faraway Ranch, pp. 22-23, 50; map in Faraway Ranch Papers.

|

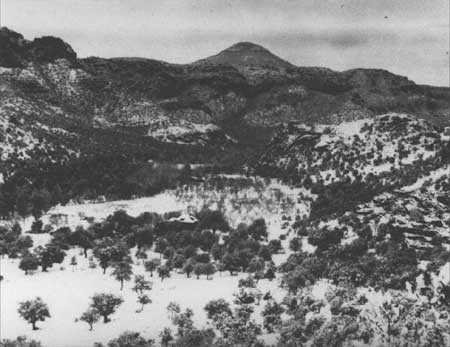

| Figure 19 — Faraway Ranch in snow, looking northeast; Stafford Cain in distance. (WACC) |

Within a few years Lillian found herself operating Faraway Ranch by herself. As of 1921 her parents were stationed at Flagstaff; Hildegard married in 1920 and moved away. No doubt it was a trying time for Lillian. She later wrote to her father, "With you and mama in Flagstaff, Hildegard married, and myself tied up with notes and the determination to pay out the Stafford place, there seemed nothing else to do but stick or die." Between 1924 and 1927 Ja Hu Stafford's son, Tom, and his wife Nora worked occasionally at Faraway Ranch, she as a cook and baker and he as a gardener and cowboy. The Stafford cabin found use for guests, relatives, friends and employees.71

71Torres and Baumler, Faraway Ranch, p. 53; oral history of Nora Swanner Stafford.

Major development of Faraway Ranch and regular use of the Stafford cabin did not begin until after Lillian Erickson's 1923 marriage to Ed Riggs, a widower with two children and former neighbor whom she had known since childhood. Lillian and Ed returned from their honeymoon and announced plans for "extensive building improvements," not only to the main ranch house but to the surrounding land including the Stafford homestead. The Riggses carried out numerous improvements from 1924 through the 1930s and early 1940s, including work on the Stafford cabin.72

72Torres and Baumler, Faraway Ranch, p. 53.

Some time between 1925 and 1927 Riggs detached and moved the third addition to the cabin to a location to the southwest across the small valley, using log rollers. A school occupied that building in 1927-1929, and in later years it was named Mizar and used as a rental cottage. Probably during this time Stafford's second addition to the log cabin, the shed porch on the west side, was removed and rebuilt as an open porch facing west; a small section on the north end of the porch was enclosed, possibly for a bathroom. Ed Riggs and some hired help built a fieldstone chimney with a brick lined fireplace on the south end of the original (south) room, which required removal of a window. Riggs installed running water and a toilet in the cabin some time after April, 1939.73

73Ibid., p. 68; interview with Donald Riggs; Murray, personal communication.

Ja Hu Stafford's granddaughter, Helen Amalong (Kenney), a daughter of Ruby Stafford Amalong, worked for the Riggses as a waitress during the late 1920s and early 1930s. She recalled a blacksmith shop still standing to the east of the cabin, as well as a corral. Stafford's circa 1898 lean-to addition on the west side of the cabin had been opened as a porch, and no other porch existed on the east side. The stone-curbed well still existed in the kitchen, but was later floored over. At the time she worked there the garage addition had yet to be built. Principally male guests and survey crews stayed in the cabin during those years.74

74Interview with Helen Kenney.

|

| Figure 20 — Map of part of Stafford homestead drawn by Ed Riggs, no date. Shows springs, orchard, etc. (WACC) |

At an unknown date the cabin's interior was paneled with plasterboard, probably after April, 1939, although the work could have happened as early as 1927, when Ed Riggs purchased a large amount of construction materials including celotex, windows, roofing, beaverboard, plumbing, and cement. That year a nearby newspaper noted that "cabins have been constructed near the house, containing five bedrooms [with] carbide lamps in the main house and lamps in the cottages." The Riggses named these cabins Alcor and Space, along with Mizar, the removed section of the Stafford cabin.75

75Billheads in Faraway Ranch Papers, Series 24, Box 40; Douglas Daily Dispatch, July 3, 1927.

With such improvements the Stafford cabin became a regular and important part of the guest ranch, where by 1942 a number of guest facilities had been built or improved. Guests at the cabin could purchase meals at the main house or cook for themselves. In one 1963-1965 brochure Faraway Ranch manager Frank W. Sullivan advertised "a limited number of modern furnished cottages are available for light housekeeping," and added, "we are compelled to exclude persons with communicable diseases."76

76Rates and descriptions in Faraway Ranch Papers, Series 11, Box 37, and Series 36, Box 59. Sullivan was manager from March 1963 to March 1965.

An early rate card, issued about 1928, listed "one log cabin, partly furnished, $1.00 per day; $20 per month. Accommodates four." The cabin, by this time, was available for short-term or long-term rental. A billhead from 1928 noted that eight workmen stayed in the cabin for ten days and paid $80.00 plus tax. Rate cards from the 1940s revealed changing prices and policies:

[circa 1940:] accommodates 4 people, complete at $15. per week, without linen and bedding, $45. per month. Meals: Breakfast .50, Lunch .50, Dinner .75, special occasions & Sunday $1.00.

[circa 1955:] bedroom w/ double bed, sitting room w/fireplace, kitchen and shower. RATE: monthly (only) 1 or 2 persons $100. Horses (for guests) $1.50 1st hour, $1.00 per hour after, $6 maximum, must have guide. Meals (at main ranch house): breakfast $1.00, lunch $1.00, dinner $1.75 weekday, $2.25 Sundays & holidays.

[another brochure same as above except:] daily 1 or 2 persons $8, weekly $48.; box lunch $.75.

|

| Figure 21 — Road survey crew at Stafford Cabin, 1932. Note fireplace has been added, west porch not enclosed, each porch not yet built. (CHIR 6187) |

The meals, usually prepared under Lillian's supervision, were served in the main house's closed in porch which contained the famous Garfield fireplace, built from inscribed stones that had been made into a monument by the Cavalry troops in 1886 on what was to become the Erickson homestead. Indications are that the meals were good but the portions watched closely by the thrifty Lillian Erickson Riggs. When Mrs. Riggs sold 80 acres of the Stafford Homestead to Silver Spur Ranch, Inc. in 1945 she reportedly agreed that meals would not be served at Faraway Ranch for ten years. A newspaper announced in 1952 that no meals would be served at Faraway Ranch.77

77Murray, personal communication; Arizona Daily Star, August 17, 1952; Faraway Ranch Papers, Series 38, Box 63.

At unknown dates the Stafford cabin received further remodeling. Probably about 1940 the Riggses built a board-and-batten garage, measuring twelve by eighteen feet, at the northwest corner of the cabin on the site of the third addition which had been moved away. The west porch was enclosed some time before 1947 and remodeled into a kitchenette. An open porch was built on the east side running the length of the cabin. A concrete slab formed the floor of the porch and acted as a foundation for the five two-by-six support posts. No dates are known for these additions, although Rose Bree of Willcox, once an in-law of the Staffords, recalled no open porch on the cabin when she visited with her husband in 1946. Helen Kenney recalled that the porch was a much later addition. A clue appeared in a rate sheet dated 1946, that stated: "2 room house, with fire-place, combined kitchen and dinette; bath and porches, garage, $20.00 per wk; $60.00 per month." This indicated that the garage and kitchenette were in place; the "porches" could include the long porch accessed from the two doors on the east side.78

78Torres and Baumler, Faraway Ranch, pp. 68-69; interview with Rose Bree by the author, May 22, 1990.