|

Christiansted National Historic Site Virgin Islands |

|

NPS photo | |

Capital of the Danish West Indies when Sugar Was King

Denmark was a latecomer in the race for colonies in the New World. Columbus's voyages to the Caribbean gave Spain a monopoly in the region for more than a century. But after the English planted a colony in the Lesser Antilles in 1624, the French, Dutch, and eventually Danes joined in the scramble for empire. Seeking islands on which to cultivate sugar as well as an outlet for trade, the Danish West India & Guinea Company (a group of nobles and merchants chartered by the Crown) took possession of St. Thomas in 1672 and its neighbor St. John in 1717. Because neither island was well suited to agriculture, the company in 1733 purchased St. Croix—a larger, flatter, and more fertile island 40 miles south—from France. Colonization of St. Croix began the next year, after troops put down a slave revolt on St. John.

For their first settlement the Danes chose a good harbor on the northeast coast, the site of an earlier French village named Bassin. Their leader Frederick Moth was a man of vision. He planned a new town—named Christiansted in honor of reigning King Christian VI—and had the island surveyed into plantations of 150 acres, priced to attract new settlers. The best land came under cultivation and dozens of sugar factories began operating. Population approached 10,000, nearly 9,000 of them slaves imported from West Africa to work in the fields.

Even with this growth St. Croix's economy did not flourish. The planters chaffed under the DWI&G Company's restrictive trading practices. This monopoly so burdened planters with regulations that they persuaded the king to take over the islands in 1755. Crown administration coincided with the beginning of a long period of growth for the cane sugar industry. St. Croix became the capital of the "Danish Islands in America," as they were then called, and royal governors took up residence at Christiansted. For the next century and a half, the town's fortunes were tied to St. Croix's sugar industry. Between 1760 and 1820 the economy boomed. Population rose dramatically, in part because free-trade policies and neutrality attracted settlers from other islands— hence the prevalence of British culture on this Danish island with a French name—and exports of sugar and rum soared. Capital was available, sugar prices were high, labor cheap. Many planters, merchants, and traders reaped great profits, as reflected in the fine architecture of town and country. This golden age was eclipsed within a few decades by the rise of the beet sugar industry in Europe and North America. A drop in the price of cane sugar, increasing debt, drought, hurricanes, and the rising cost of labor after slavery was abolished in 1848 all contributed to economic decline. As the 19th century wore on, St. Croix became little more than a marginal sugar producer. The era of fabulous wealth was a thing of the past. When the United States purchased the Danish West Indies in 1917, it was for the islands' strategic harbors, not their agriculture. The lovely town of Christiansted is now a link to the old way of life here, with all its elegance, complexity, and contradiction.

Before the Danes

This island's first settlers migrated up the Lesser Antilles from South America. By 2,000 years ago there was a settlement at Salt River Bay on the island's north shore. By 1300 the village there had the only ceremonial plaza/ball court so far discovered in the Lesser Antilles. On his second voyage, in 1493, Columbus came upon this island and named it Santa Cruz (Holy Cross). Sighting the village at Salt River Bay, he sent a boat ashore to "have speech with the natives." The Spaniards met a canoe with Caribs. A fight ensued. One Carib was killed, and the rest were captured. Two Spaniards were wounded, one fatally. It was the first documented skirmish between Europeans and New World natives.

Regulars and Militia

Though Denmark relied mostly on neutrality to defend its far-off tropical colonies, a military presence was essential in a region dominated by European rivalries and slave labor. On St. Croix, defense rested on a system of forts and batteries garrisoned by regular Danish troops. The fort in Christiansted was finished in 1749. Captured leaders of the 1733 slave uprising on St. John did some of the construction work.

Named Christiansvaern ("Christian's defense") in honor of King Christian VI, the fort was armed with 18- and 6-pounder cannon. These guns and two outlying batteries, combined with a formidable reef, dominated the harbor entrance.

Under Gov.-Gen. Peter von Scholten, an aristocrat with a taste for ceremony, the military on St. Croix enjoyed perhaps its best years. Von Scholten reorganized the regulars and enlarged militia units and the fire brigade. Free Blacks filled the ranks of the latter and also served in the militia. Christiansted's garrison in 1830—at least on paper—numbered 215 officers and men, including a corps of musicians. This was nearly half of all regulars in the Danish West Indies.

Free Blacks

In the days of slavery a distinct class, Free Blacks, emerged on St. Croix. Some were given their freedom for faithful service; others bought freedom with money earned as artisans or by raising and selling produce from their gardens in the Sunday Market. They worked as small merchants, fishermen, seamen, shoemakers, tailors, masons, coopers, carpenters, and blacksmiths.

As early as 1747 a section of Christiansted, Neger Gotted—later called Free Gut—was set aside for Free Blacks to build their own houses. Between 1791 and 1815, the town's Free Blacks more than doubled their numbers, rising from 775 to 1,764. Not until 1834 were they granted full equality with whites. Free Black status for men was indicated by a red-and white cockade worn on their hats.

In The West Indian Style

Christiansted blends vistas of neoclassicism with a lovely natural setting of high hills and reef-fringed harbor. The town's orderly development over two centuries owes much to the island's first governor, Frederick Moth. He conceived of Christiansted as a grand town like Christiania (now Oslo) in Norway, with boulevards, promenades, and handsome building lines. He put government buildings and townhouses near the waterfront, relegating workers' cottages to the outskirts. A remarkably progressive building code embodied his ideas in 1747. Enforced by successive building inspectors, the code regulated materials and construction and even used zoning to regulate growth. Forms of the code were in force throughout Danish rule, and economic stagnation after Danish rule helped the town survive passing building fads.

Christiansted took shape at a liberating moment in architecture. The neoclassic style of the 1700s came to dominate the Danish islands, reflecting the wealth accumulated in their first century. The buildings were the work of anonymous craftsmen—masons and carpenters, many of them Free Blacks—in a day when a master mason or carpenter could both plan a building and put it up. West Indian neoclassical at its best is dignified, solid, and functional. Buildings feature rhythmical arches, light and spacious interiors (often filled with fine mahogany furniture), arcaded sidewalks to shelter pedestrians from sun and rain, galleries to catch breezes, and hip roofs that collect rainwater in cisterns. Yellow bricks that came as ships' ballast saw wide use in construction. Buildings from Christiansted's golden age are: wealthy merchant or planter's townhouse, Steeple Building (the first Danish Lutheran church on St. Croix), Government House, merchant's shop/residence, and worker's cottage.

Saint Croix's Golden Age of Sugar

The Sugar Plantation

For a time St. Croix was one of the wealthiest sugar islands in the West Indies. The good years coincided with wars between colonial powers. In the late i8th and early 19th centuries production was high, and the price of sugar on the world market was stable. In 1803 the island's population was 30,000—26,500 were slaves who planted, harvested, and processed cane on 218 plantations. More than 100 windmills and almost as many animal mills ran night and day in season, converting sugar into wealth.

Growing sugar was hard work. The idea of the "indolent planter" is mostly myth. A planter and his manager had to know how to plant a crop and bring it in; how to make sugar, molasses, and rum and get them to market; how to build; how to motivate enslaved labor; and how to deal with island merchants, ship captains, and bankers. Work went on year-round. For the ambitious and ingenious, a plantation was an all but certain way to a fortune. But for most planters it was a business loaded with risk.

Planters contended with drought, hurricanes, fluctuating market prices, and the hazards of shipping. Considerable investment, much of it borrowed at high rates, was needed for buildings and machinery as well as land and slaves—because a planter was as much a manufacturer as a farmer. Sugar production was a highly integrated process from field to market that, in fact, foreshadowed the coming industrial age.

Most plantations were small communities of 225 to 300 acres, but not self-sufficient. Much food, clothing, and equipment was imported. Two-thirds of the land grew cane; the rest contained dwellings, garden plots for provisions, pasture, and the large, T-shaped factory building. In it cane was transformed into raw sugar called muscovado. The factory was part of an industrial complex: a great stone windmill for squeezing juice from cane, a boiling house for reducing the juice to crystals, curing houses for drying sugar and draining off molasses, warehouses, and a distillery for turning molasses into rum. The manager's house and slave village stood nearby. The first slave dwellings were of wattle-and-daub construction. Later ones were of masonry, usually built by the slaves themselves as single cottages in orderly rows. The "greathouse"—dwelling of the planter and family—was the glory of the plantation. Nothing so manifested a planter's luxurious mode of living. Often built by slaves, it usually sat on commanding ground, surrounded by the carriage house, stables, quarters for house servants, and other dependencies. It was a work of art illustrative of an age.

The best days were over by 1820. Competition from beet sugar, coupled with slave emancipation in 1848 and sporadic hurricanes, drought, and labor unrest through the balance of the century, contributed to an irreversible economic decline. When the last sugar plantations ceased operating in the late 1920s, those who labored in their fields and factories did not lament their passing.

Fields of Cane

Sugarcane worked a revolution in Caribbean life. After sugar caught on as a staple in the French and English islands about 1650, plantations replaced small farms, and indentured labor gave way to chattel slavery. Wealth accumulated at the top of the social order and misery at the bottom. Society on this island and in the West Indies generally is today the heir of these beginnings.

Sugar cane is an Old World species, a member of the grass family, and grows readily in this climate. Work began in the fall, the rainy season, with gangs of slaves digging trenches for cuttings. Sprouts were weeded until knee high, and 16 months after planting the cane was 10 feet tall and ready for cutting. The harvest was the busiest time of the year. Working from first light to last, slaves stripped off the leaves, cut down the cane with their hooked bills, and loaded the stalks into carts for the mill. Grinding went on night and day. Workers passed the canes through the mill's rollers twice to increase juice extraction. The juice dripped into a collection box and from there ran by trough to the boiling house.

Wind Power and Animal

Plodding teams of oxen or mules powered the islands' earliest mills. They turned long poles attached to vertical rollers that extracted juice from the cane fed into them. Beginning in 1750 the planters, with slave labor, built scores of wind-driven mills on high ground to catch the trade winds. In 1794, 100 windmills and several dozen animal mills were operating on St. Croix.

The Greathouse

The greathouse was a planter's joy and pride. It was usually built in the prevailing neoclassical style by slave labor, including craftsmen. Like the mill, the house sat on high ground to catch prevailing breezes. From the gallery a planter could survey his domain. The earliest estate houses on St. Croix were relatively modest wooden affairs, with separate kitchens to reduce the risk of fire.

From the 1760s on, accumulated wealth enabled planters to build with limestone and brick. Some houses featured a staircase sweeping up to the main level—to a parlor, dining room, bedrooms, and perhaps an office and library. The rooms were airy with high ceilings. A planter's wife would go to great expense to fill the house with fine mahogany furniture and imported silver, crystal, porcelain, and linen. The most important supporting buildings were the cookhouse (with banks of ovens and grates), stables, and servants' quarters.

Presiding over this world the planter's wife saw to all things domestic and frequently organized sparkling socials that brightened island life. She was helped by a host of servants, usually specially selected blacks brought into the household to cook, clean, tend children, and look after the horses and carriages. The duties of these blacks and their relationship to the planter and his family gave them a measure of independence and considerable rank over field hands.

Making Sugar

Cane juice flowed straight from the mill to the boiling house, where it was reduced to a moist, brown sugar called muscovado. A boiling master, usually a slave valued for his skill at the process, directed work. Along one wall stood a receiving vat and next to it a battery of successively smaller cauldrons, called coppers, over furnaces fueled by bagasse, dried crushed cane stalks.

On the opposite wall were shallow cooling pans. After skimming off impurities and adding lime, workers ladled the juice from copper to copper, stirring and skimming. At the last and hottest copper, the rapidly thickening juice was carefully watched over. If the boiling master could produce a sugary thread between his thumb and forefinger, cooking was done. At his cry of "strike," workers turned the moist crystals into wooden pans to cool. This sugar was packed in hogsheads, huge barrels of 1,600-pound capacity. They were put on racks and the molasses drained off. After a few weeks, when the sugar was dry, the hogsheads were topped off with fresh sugar, sealed, and then loaded on oxcarts for transport to the town wharf for export.

Molasses was a lucrative byproduct Most was used to make rum for export to Europe or North America.

Distilling Rum

Rum was the staff of West Indian life and a plantation's second product. It was made by fermenting water and molasses, five parts to one in a vat (1) with a measure of skimmings, oranges, and herbs to taste. After a week the mix was heated in a still (2). Vapors passed to a doubler (3), gaining strength, and from there through condensing coils (4) into a vat (5). Emerging as 120-proof rum, it was aged and barreled for export. Crucian rum was among the best.

Life of the Blacks

From settlement in 1734 to the abolition of Denmark's slave trade in 1803, tens of thousands of blacks—the exact number is not known—were shipped to St. Croix to work in its fields. Their hard, monotonous labor underlay St. Croix's wealth. They worked from dawn until dark, with two hours off for a meal, six days a week. At crop time they worked around the clock, followed by a few days of festivity, a yearly high point for slaves. Males and females, with children in tow, labored together to plant, weed, or cut in season. Men worked in the mill and boiling house, tended stock, carted sugar to the dock, served in the household, constructed buildings, and became artisans. Amenities were few. They lived in masonry huts that they built themselves, arranged in rows for control. They sewed their clothing from annual allotments of fabrics. Food was scanty: to corn meal and salt fish they added produce from their garden plots. They sold surplus produce in the public market. Despite slavery, some African customs persisted in language, religion, and foods.

Exports and Imports

St. Croix lived by trade. The island exported five commodities—sugar, rum, molasses, cotton, and hardwoods—and imported (as it does today) nearly everything it used or consumed. Much of this cargo rumbled across Christiansted wharf in ox carts driven by slaves and was loaded on ocean-going vessels. When yields were good and prices high, planters lived lavishly; spent freely in London, Copenhagen, or Philadelphia on equipment, food, and luxuries; and paid off debt.

Until Denmark ended its slave trade in 1803, Christiansted was an important port in the infamous Triangular Trade that took cheap goods from Europe to Africa, slaves to the Caribbean, and sugar and molasses to New England or Europe. The Middle Passage was sheer horror. So many dead and dying were tossed overboard, said one captain, that "the sea lanes to the West Indies were carpeted with the bones of black Africa." At Christiansted survivors were herded into the compound of the DWI&G Company and auctioned off to the planters and city dwellers.

The Napoleonic Wars and British occupations (1801, 1807-15) interrupted old trade patterns with Europe and the United States. As peace returned, the United States soon became the island's chief trading partner. The link even survived high tariffs protecting the fledgling U.S beet sugar industry. Long attracted by the islands' good harbor—and also fearing encroachment by Germany—the United States purchased the islands from Denmark for $25 million in 1917. The sale merely made formal a long-standing economic relationship between the United States and the Virgin Islands.

Visiting the Park

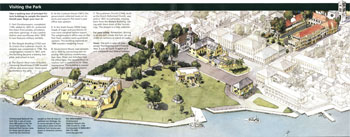

(click for larger map) |

Take a walking tour of principal historic buildings to sample the town's Danish past. Begin your tour at:

Fort Christiansvaern, completed 1749, added to 1835-41, protected the town from pirates, privateers, and slave uprisings. It was a police station and courthouse after 1878. It now features military exhibits.

The Steeple Building (1753) was St. Croix's first Lutheran church. Its steeple was completed in 1796. The congregation moved in 1831, and the building became a bakery, hospital, and school in turn.

The Danish West India & Guinea Company Warehouse (1749) housed offices and storerooms. Slaves were auctioned in the yard.

At the Customs House (1841) the government collected taxes on imports and exports. The town's post office was upstairs.

In the Scale House (1856) hogsheads of sugar and puncheons of rum were weighed before export. The weighmaster's office was on the first floor; soldiers were quartered upstairs. This building replaced an 1840 wooden weighing house.

Government House was completed in 1830 by connecting two imposing 18th-century townhouses. Gov.-Gen. Peter von Scholten had his office here. The second-floor reception hall is restored to its 1840s appearance. The building is owned by the Virgin Islands government.

The Lutheran Church (1744), built as the Dutch Reformed Church, was sold in 1831 to Lutherans, moving here from the Steeple Building, taking with them most of the furnishings. The steeple is a later addition.

For your safety Remember: driving is on the left. Inside the fort, do not climb on cannons or stand on walls.

Hours The park is open all year, except Thanksgiving and Christmas days, 8 a.m. to 5 p.m. It opens at 9 a.m. weekends and federal holidays.

Source: NPS Brochure (2004)

|

Establishment

Christiansted National Historic Site — January 16, 1961 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

Cultural Landscape Report, Christiansted National Historic Site, St. Croix, Virgin Islands (Robert Bradley, January 5, 1985)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory: Cultural Landscape, Christiansted National Historic Site (December 2021)

Foundation Document, Christiansted National Historic Site, U.S. Virgin Islands (January 2015)

Foundation Document Overview, Christiansted National Historic Site, U.S. Virgin Islands (February 2015)

Historic Architecture of the Virgin Islands Selections from the Historic American Buildings Survey No. 1 (February 1966)

Historic Furnishings Report: Fort Christiansvaern, Christiansted National Historic Site, Virgin Islands (Jerome A. Greene and William F. Cissel, 1988)

Historic Structure Report for Danish West India & Guinea Company Warehouse (GCW) (CRIS HS 7029); Historic Kitchens Nos. 1 & 2; the Public Restroom; Site Features — Exterior Walls, Cisterns and Gates; and the GCW Paint Analysis (The Collaborative Inc. and Atkinson-Noland & Associates, Inc., February 10, 2020)

Historic Structure Report: Fort Christiansvaern and Stable Building: Volume 1 (Jospeh K. Oppermann-Architect, 2023)

Historic Structure Report: Fort Christiansvaern and Stable Building: Volume 2 (Jospeh K. Oppermann-Architect, 2023)

Historic Structure Report: The Steeple Building, Christiansted National Historic Site (Quinn Evans and VHB, May 2024)

Historic Structures Report/Historical Data: Steeple Building, Christiansted, St. Croix, U.S. Virgin Islands, Part I (Herbert Olsen, November 1960)

Masonry Forts of the National Park Service: Special History Study (F. Ross Holland, Jr. and Russell Jones, August 1973)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Forms

Christiansted Historic District (Russell Wright and Thomas Richards, May 22, 1976)

Christiansted National Historic Site (Frederik C. Gjessing, June 15, 1973)

chri/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025