|

Colorado

A Classic Western Quarrel: A History of the Road Controversy at Colorado National Monument |

|

CHAPTER FOUR:

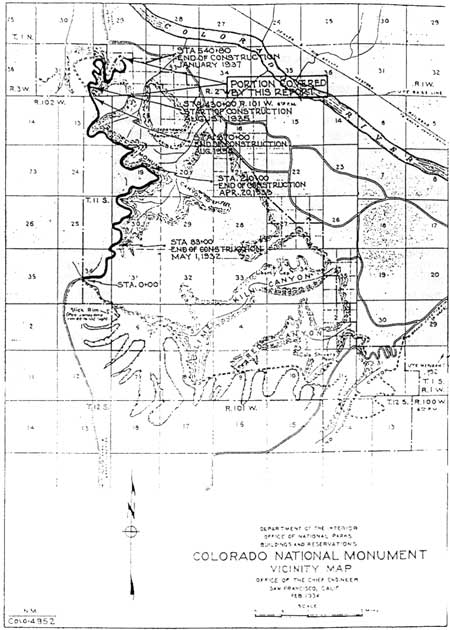

Construction of Rim Rock Drive: 1931-1950

The initial years of road construction in the Colorado National Monument occurred during the Great Depression. The 1929 collapse of the nation's economy affected nearly every aspect of American life. Businesses failed, farms were lost, unemployment increased and the average income decreased. [270] In Colorado the depression developed more slowly. Because its economy was primarily based on agriculture, Colorado felt less of the economic downturn until after 1930. Unemployment increased and agricultural prices fell more slowly than elsewhere. Yet, by 1931, cities such as Denver and Pueblo experienced more unemployment. Rural Coloradans suffered and as agricultural prices dropped, they headed for the cities when they lost their farms. The environmental impact of the dust bowl and the decline of the economy, combined to force farmers to leave for the city. [271]

The depression had a surprisingly less dismal effect on the National Park Service and congressional appropriations for park development. In 1930, appropriations increased by $3 million. Tourist levels remained steady. Road construction was the one aspect of park development that received the most attention during the depression. Across the nation, various national parks, such as Rocky Mountain and the Grand Canyon, received grants for road construction. Road appropriations in 1931 expanded to include the improvement of approach roads to parks as well. That year, approximately $100 million was appropriated for roads to and through national parks and monuments, including $75000 for the Colorado National Monument. [272]

Road Construction, 1931-1933

Between 1931 and 1933, local and federal involvement in the Colorado National Monument occurred simultaneously. Once the $7500 appropriation was available to the Colorado National Monument, the National Park Service and the local community immediately planned for the initial construction of the road through the park. In the first week of November 1931, Park Service engineer T. W. Secrest conducted a reconnaissance of the Colorado National Monument in which he developed and submitted road surveys to the Washington office for approval. [273] The reconnaissance consisted of eight days spent "studying and traversing the monument and approach roads." [274] Part of this survey included the pipe line road leading up to Fruita Canyon on the park's west side. County officials stated that they would improve this road, "thus making a connection with a county highway leading from the trail of the Serpent." [275] County officials also offered to "furnish any equipment they had idle" for the construction of the road. [276]

The Grand Junction Chamber of Commerce influenced the course chosen for the road. It wanted a road from which people could view the more impressive of the park's features from their automobiles. This route was more expensive because it required cutting through more cliffs, but eventually the Park Service agreed to it. [277] The ultimate goal was to construct a complete loop from Grand Junction to Fruita via the Monument. The route stretched from the Serpents Trail through the Monument and eventually emerged in Fruita Canyon on the western end of the park. The original plan entailed construction of a "single-width highway of about twenty-four miles," which followed the approximate route of today's Rim Rock Drive." [278]

In addition to suggesting possible routes for the road; the chamber of commerce contributed funds and some labor to the National Park Service. Local funding of the road project, combined with Park Service appropriations, enabled early construction. The Grand Junction Chamber of Commerce, working in conjunction with a presidential committee, expended funds acquired from local sources. Although the amount of funding was relatively small, it did contribute to the construction effort. [279] The chamber requested federal emergency relief funds to reduce unemployment in the Grand Valley. It also suggested that the Park Service choose Secrest to head the road project. [280] Taylor discussed the chamber's requests with Horace Albright. He tried to convince Albright that the initial construction should begin not just for the "expeditious development of the Monument" but also to "relieve unemployment." [281] Albright responded by stating that funds were not available for the construction of the entire road but that he would authorize funds for the first section of construction. [282]

Just weeks before construction began, the Park Service's plans were interrupted. During the second week of November, 1931, the chamber of commerce and county commissioners, anxious to start construction, authorized the beginning of work on the road to the Monument boundary. They even donated equipment to the cause. [283] The National Park Service, however, wanted to postpone construction until a landscape architect evaluated the proposed routes. The Park Service also wanted a full description of the road project to be approved by its offices in San Francisco. [284] When these issues were resolved, construction officially began on November 21, 1931.

The first section of construction, from Station 0+00 Section 1B to Station 83+00 Section 1B, was chosen for a number of reasons. [285] The construction began near the center of the present Rim Rock Road, and headed west toward Fruita Canyon. The goal was to make the scenery of the Monument Canyon accessible to tourists as soon as possible, so construction started near the canyon rim. Monument Canyon contained the park's most outstanding physical features—the monoliths—but access to it was limited. Initiating the construction in this section was also important because it completed the loop from Grand Junction to Fruita. Because the Serpents Trail was already built on the east side of the park, it made sense to start where this road ended. According to this construction plan, part of the loop was already completed. [286] During the first phase of construction, about 50 men from all over Mesa County were employed by the project, which provided some of the only work to the county's unemployed. The project benefitted local businesses, because workers had money to spend on goods and project officials purchased construction supplies from local stores. [287]

Not everyone supported what was happening. Almost from the moment construction began, Otto found reasons to protest. He felt that the chosen route was a "half mile off course," and that construction should be halted until improvements were made. He was also concerned that the road would not conform with the scenery of the park. [288] Otto intimated that local supporters of the Monument were kept in the dark regarding the use of funds. [289] His real complaint seemed to be that the chosen route would damage the landscape in the Monument:

There is a shameful misuse of federal funds at the Colorado National Monument. Your tinhorn landscape engineers and the wild construction engineer (T.W. Secrest) and your Chief Engineer F.A. Kittredge should have the steam shovel around their necks and get sunk in the Pacific. You never went over and studied this project and the engineers did not either, and naturally things just 'went haywire'. Come here and 'face the music'! When you throw a rock through a plate glass window it is ruined-spoiled-wrecked, but you can send to the factory and get a new one. But real elegant fine scenery once torn into like they did here at this high class scenic project—makes it bad. [290]

Not surprisingly, Otto's complaints were disregarded by the local park promoters and by Park Service officials, who were pleased with how construction was progressing. When Secretary of the Interior Ray Lyman Wilbur responded to Otto, he explained that the Rim Rock Road project had been carefully planned according to Park Service regulations, and that one of the engineers' primary objectives was to consider the landscape during construction. He pointed out the importance of the road project to the local economy. [291] Thomas Vint, the Chief Landscape Architect of the project, was less diplomatic in his opinion of Otto. He contended that Otto's letters were "the work of the hand of a fanatic." [292]

Despite overwhelming disapproval, Otto continued to harass officials until the spring of 1933, when he left for Yreka, California. He never returned to the Colorado National Monument. A combination of factors contributed to his departure, but perhaps the most compelling of these was that during the 27 years that he had resided in the Grand Valley, his credibility with the local community and with the National Park Service had diminished. When he left, the Colorado National Monument was no longer the place he originally boosted. It was now officially recognized by the Park Service, and its development was taken seriously by that agency for the first time in its history. [293]

Along with Otto's complaints, the initial phase of road construction raised the more serious question of future funding—never a reliable factor. Between 1931 and 1933, financial support for the road was contingent upon yearly congressional appropriations. In February, 1932, Albright, anxious to supply funds for unemployment relief in the Grand Valley, assured the chamber that the National Park Service would secure an additional $4000 to carry the project until the 1933 appropriation. After that, he wasn't sure if Congress would allot money out of the $950,000 available for road construction. [294] In March, 1932, Albright wrote to Congressman Taylor to discuss future funding. Estimating that it would take an additional $192,000 to construct the remaining sections of road, he told Taylor that he thought he might be able to allot another $15,000 to extend the road to the Coke Ovens area, but that money for the next section of road depended on the Roads and Trails appropriations for the year. [295] Between November 21, 1931, and May 1, 1932, a total of $17,474.52 was allotted by National Park Roads and Trails funds for the construction of the road. This amount included the initial allotment of $7500 from the Park Service and $1500 from the Grand Junction Chamber of Commerce. In July, 1932, the additional $15,000 was appropriated; followed by $50,000 from an Emergency Relief Fund in August, 1932. [296]

Local funds also contributed to the road project. By June, 1932, the Mesa County Commissioners had expended a total of $10,000 on the improvement of Serpents Trail and the construction of four miles of roadway from the Glade Park store to the Monument boundary where Secrest's road survey began. In a letter to the Park Service, the Chairman of the local Monument Park Committee, L.W. Burgess, observed that enthusiasm for the road project was widespread:

Hundreds of people are driving to the end of the road each week and it is our belief that when the road is completed the drive will be one of the most popular in any of your parks. [297]

Local and Park Service perspectives of the road project were similar. Both saw the importance of the project to unemployment, although the Grand Junction Chamber of Commerce was more nervous about the possibility of interrupting the project due to lack of funds. Shortly after construction on the first section began, the chamber had already established its own "Emergency Committee for Employment," which contained a list of 700 potential workers. Members of the chamber often visited the project site, and had already begun a campaign urging local residents to "come here for the Monument Drive." [298] The chamber of commerce estimated that in 1932 there were 18,000 visitors, and in 1933 there were 20,000 to the Colorado National Monument. Estimates such as these convinced both the local community and the National Park Service of the importance of continuing the road project. [299]

Support for the road project, however, extended beyond the chamber of commerce. Grand Junction lawyer Samuel McMullin wrote to Congressman Taylor in early 1933, expressing his appreciation for the road project's influence on economic conditions in the Grand Valley. He was especially impressed with T. W. Secrest's work:

... he has exercised a great deal of care in giving local destitute people employment on this work, going to the extent of staggering the work around so as to benefit the most number of people. Unfortunate and destitute ranchmen have been enabled through this work, to provide for the necessities in a considerable number and a good portion of the expenditures have been for labor. This has resulted in helping the small storekeeper, who is as necessary and needs as much assistance as anyone in these times. [300]

The Park Service also recognized the importance of the project, and appreciated the local attitude toward it, as is evidenced in a letter from Horace Albright to Congressman Taylor in early 1932:

Of course when we started this project this winter to help relieve conditions around Grand Junction we did not expect to go into it on such a large scale although I knew that we could not build roads in that country for the small amount of money which the local people were claiming the road would cost. However, we have such splendid cooperation from the local people and the road work has helped so tremendously in tiding men over this winter that we have felt obligated to go along with it just as far as we possibly could [301]

From 1931 to 1933, the local role in land acquisition for the park indicated that in addition to supporting the road project, local residents were also interested in expanding the park. There were two instances in which acquisition of lands outside Monument boundaries was deemed necessary to continue construction as planned. The first of these was the land surrounding the Fruita water pipeline that ran through Fruita Canyon to several reservoirs on Glade Park and provided the municipal water supply for Fruita. In late October, 1932, the town of Fruita agreed to supply water to the Monument during the construction for an annual fee of $10. [302] In January, 1933, Fruita officials agreed to grant free use of water during the construction. They realized the importance of the project to their town and the surrounding communities and the necessity of their water to the project's success. [303] Perhaps the pipeline's proximity to the Rim Rock Road prompted Fruita's eventual decision to donate the pipeline land to the Colorado National Monument. In a deed dated September 5, 1933, Fruita transferred the land but reserved "an easement for the maintenance and operation of a reservoir." The deed stated that the easement would not "interfere with the operations of the Monument." [304]

The community also acquired property in Fruita Canyon and No Thoroughfare Canyon that was considered necessary for road construction. Congressman Taylor was actively involved in this endeavor, and encouraged the Park Service to survey these lands. In an inspection of the Monument, Taylor found that in order to ensure proper grading for the road, portions of it would have to be constructed outside the boundary. [305] Taylor felt a presidential proclamation was all that was needed to acquire the lands. Nevertheless, he feared that once people learned of this, they might file on it in order to sell it later for a high price. [306]

The Park Service agreed to submit a presidential proclamation for the land. In the meantime, the Grand Junction Chamber of Commerce attempted to purchase certain privately owned portions of the property. [307] One section of land that the chamber sought to acquire, owned by William Streb, was part of No Thoroughfare Canyon. [308] The chamber stated that it would raise $400 and requested that the Park Service pay the other half of the $800 purchase price. The Park Service replied that it could not supply federal funds until a presidential proclamation was secured to include the Streb lands. [309]

While the National Park Service compromised with the chamber regarding privately owned lands, it also devised a plan to acquire former Ute treaty lands. Portions of the land that the Park Service wanted to acquire had once belonged to the Utes. Under the Ute Indian Treaty of 1880, this land was subject to a fee of $1.25 per acre to be paid to the Ute Indians. [310] Congressman Taylor offered to introduce a bill in Congress that requested the $1.25 per acre payment. This bill, and the chamber's purchases, were expected to convince officials in Washington of the need for a presidential proclamation. [311] On March 1, 1933, the Secretary of the Interior, Ray Lyman Wilbur, submitted to the President of the United States a proclamation that suggested the following boundary changes:

This proposed proclamation amends the description of the Colorado National Monument so as to include additional scenic and scientific and other features. Also it extends the boundaries so as to include the Rim Road and other land to facilitate the administration of the monument. This proposed proclamation would add to the present monument approximately 3,800 acres. Of this area 3,089.74 acres are public lands and 200 acres are owned by the Town of Fruita for park purposes. The remaining land, approximately 500 acres, are in private ownership. However, the proclamation is made subject to all valid existing rights. [312]

On March 3, 1933, President Herbert Hoover signed the proclamation, thus changing the Monument's boundaries. In the preface to the proclamation "the protection of the Rim Road" was cited as one of the reasons for the additions to the park. [313]

From 1931 to 1933, the National Park Service benefitted from, and even relied on, local needs resulted in cooperative interaction between these two parties. Yet, for the first time since the park was established, the Park Service had a physical presence in Colorado National Monument that began to erode direct local involvement in the park's planning and development.

Road Construction, 1933-1942

Between 1933 and 1942, a new phase of construction began with the establishment of the Civilian Conservation Corps and other federal work camps in and near Colorado National Monument. Overall, the CCC had an extraordinary impact on the National Park System. Plans for this work program began during the depression when unemployment rose 22 percent between 1929 and 1933. Unemployment among the nation's young men increased faster than overall unemployment. The "dust bowl" convinced many people that the nation's natural resources were being abused. Conservation programs had been instituted in some states already. While he was governor of New York, Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1929 convinced stare legislators to pass county and state reforestation laws. By 1931, New York state legislators established an emergency relief administration, in which the unemployed were hired to do reforestation work, fight fires, construct roads and trails, and complete other jobs. In August, 1932, the Society of American Foresters discussed a similar program, in which men would work in national and state parks on various problems, including soil erosion, watershed protection, and road and trail construction. After Roosevelt's election in November, 1932, he requested that Chief Forester, Robert Y. Stuart, design a plan for the employment of 25,000 men in federally owned forests. The plan was never approved, but Roosevelt used it to design the CCC. [314]

During his inaugural address on March 4, 1933, Roosevelt discussed the importance of preserving both human and natural resources in the country. By March 9, 1933, he had called a conference with members of his cabinet to discuss a program, in which the Army would recruit and supervise 500,000 men in work camps throughout the United States. According to this plan, the Departments of Agriculture and the Interior would oversee work projects assigned to the camps. A bill was drafted but was withdrawn from congressional consideration due to overall opposition and weaknesses in the plan. In March, 1933, the Roosevelt administration formulated a more precise bill, in which states received grants for relief, a broad public works program was initiated, and soil erosion and forestry programs were planned. Once the bill was submitted, Congress added its own conditions; in return for forest fire prevention, construction of roads and other work, men would receive room, board, a salary, and other benefits. Under this bill, which eventually became the Federal Unemployment Relief Act, enlistment of men was set at one year, workers earned $30 per month, and part of that salary was sent home to dependents. [315]

The bill was signed on April 3, 1933. On that day, Roosevelt gathered his cabinet members and assigned duties. The Department of Labor started nationwide recruitment; the Army trained and transported enrollees to camps; and the Park and Forest Services supervised the work and the camps. Later, the Army supervised the camps while the Park Service coordinated work assignments. The April 3 meeting produced more changes in the program; enrollees had to be between the ages of 18 and 25, and they had to send at least $25 of their salary home each month. Roosevelt stipulated that each camp be composed of 200 men with enrollment periods of six months. He also personally approved camps and work assignments. The workforce varied. The Park Service often hired a certain percentage of locally employed men (LEMs) but most of the workers were from larger urban regions. [316]

Emergency Conservation Work (ECW), precursor to the CCC, officially began on April 5, 1933. The program started with an initial enrollment of 25,000 men. At first, the National Park Service and the U.S. Forest Service were overwhelmed by large numbers of enrollees, problems with work projects, and the impact of restrictions on work camp locations. Yet, by May of 1933, the Park Service was ready to employ 12,600 men in 63 camps located in national parks and monuments across the country. [317]

Colorado benefitted a great deal from the CCC. By the spring of 1933, 30 to 35 camps were established in the Colorado District. The Grand Junction District had 20 camps. [318] Enrollees were organized and trained by Colonel Sherwood A. Cheney at a reconditioning camp set up at Fort Logan, Colorado. By mid-May, 1933, workers were shipped from Fort Logan to posts across the state, and Colorado's CCC officially began its work. [319] The CCC in Colorado ultimately had a positive impact on nearby communities. While some communities were not in favor of the camps, most found that the CCC not only provided jobs, but was also a social outlet. The relationship was reciprocal. Many CCC camps relied upon local communities to achieve success in completing projects. In the Colorado National Monument, for instance, the camps' water supply came from the Fruita water pipeline. When drought hit the Grand Valley in November, 1934, camp water mains were closed, and water was shipped from Grand Junction. [320] In addition, it was not at all unusual for the CCC to become involved in community activities. In some instances, camps were responsible for flood relief, and even participated in search parties for missing persons from the community. [321]

The CCC and Federal Work Camps at Colorado National Monument, 1933-1942

The original federal work camps were established in the Colorado National Monument to ease poor economic conditions in the Grand Valley, and to provide more labor on the Rim Rock Drive project. In spring 1933, local business leaders urged government officials to assist in acquiring emergency employment relief for the Grand Valley. The Grand Junction Chamber of Commerce appealed to the Secretary of the Interior, Harold L. Ickes, to include in the next emergency relief bill funding to extend the Rim Rock project through the year. The chamber stated that the project had been "immensely valuable in relieving unemployment" and that the completed road would accommodate the local region in addition to opening up a "magnificent scenic area." [322] Grand Junction's mayor, F.R. Hall, requested Albright's help in securing emergency employment relief. Hall argued that the Rim Rock project was "one of [few] Colorado projects which affords year around employment under ideal conditions." [323] In a letter to Congressman Taylor, the secretary of the Grand Junction Rotary Club, George A. Marsh, also expressed his views regarding the Monument project:

We are of the opinion that no work in Colorado could be more practical or constructive than the Colorado National Monument project, and although we would welcome forest work, we believe that there is little if any such work that could compare or surpass in economic value that of the Monument. ... Probably few government projects have been given financial aid by local communities comparable with that of our Monument. [324]

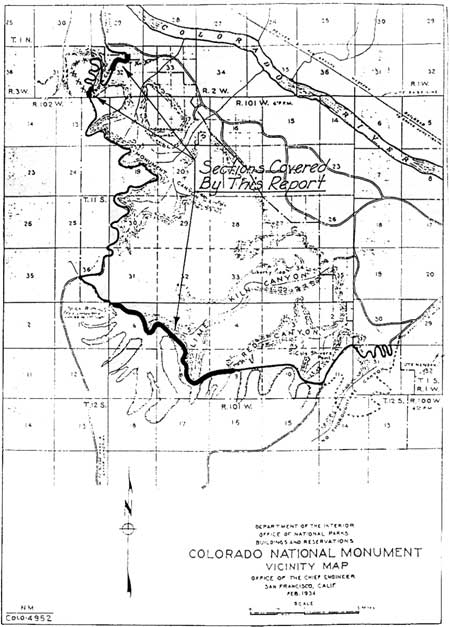

Colorado National Monument's first 200-man camp was approved in April, 1933, and was a sign that heavy federal involvement in the road project had begun. Although local park promoters still contributed funds to the road project, once the federal work camps were established, most of the major decisions about the park and the road were made by the National Park Service. Because funding was not yet available, the Park Service decided that it wanted T.W. Secrest to serve as superintendent of the camp. [325] On May 20, 1933, Company 824, consisting of a commanding officer, a medical officer, a staff sergeant, two corporals, a private, and four enrollees, was organized at Fort Logan and sent to start a camp for the Colorado National Monument. This camp was designated NM-1-C. [326] When officers arrived, mess and barrack tents were already set up in anticipation of 220 men. Water was supplied by the Fruita pipeline, and necessities were transported over newly cut roads. During the next few days, 26 LEMs and 50 Colorado Juniors from Mesa County were hired. That summer an additional 12 LEMs and 113 Colorado Juniors were employed. Camp NM-1-C was originally setup near the Coke Ovens on the rim of Monument Canyon. Due to cramped conditions, it moved to a permanent location at Camp NM-2-C at the Saddle Horn near the present site of the Visitor Center. Company 825, known as NM-3-C, was originally set up near Glade Park in November 1933. Eventually this camp moved to the base of Fruita Canyon in June 1934. Enrollees from these camps worked on sections of the Rim Rock Drive under the direction of T.W. Secrest. [327]

Life in the work camps at the Colorado National Monument included a variety of elements: army discipline, educational benefits, and work experience. The U.S. Army and the Park Service split the responsibility of camp management. The army supplied materials, uniforms, and personnel needed to train, feed, and organize social and recreational events for the enrollees. [328]

After December 1, 1933, regular army officers returned to their duties, and reserve officers supervised the majority of camps in the Colorado district. [329] While in camp, enrollees were under the authority of an army commanding officer. In some cases LEMs and other enrollees served as barracks leaders. The Park Service, on the other hand, supervised the work projects in the park. It hired a foreman and an engineer to supervise the LEMs and the enrollees while they worked on projects throughout the park. [330]

Along with the discipline, enrollees were introduced to educational and recreational opportunities. Camp NM-2-C provided classes in typing, bookkeeping and accounting in addition to woodworking and photography. It also boasted a library of 400 volumes. At one point, 80 percent of the workers were involved in aspects of the educational program in NM-2-C. Camp NM-3-C produced its own newspaper, known as Monument Murmurs, which was printed every two weeks. A stone recreation facility was built for the enrollees of NM-2-C to enjoy in their free time. Enrollees from both camps also participated in numerous intercamp athletic events. [331] In fact, a baseball diamond was constructed in Camp NM-2-C-now the Saddlehorn parking lot in May 1934. [332]

Construction was an enormous undertaking financially and physically. Between 1932 and 1937, funding from a variety of sources fueled the road project. Among those providing funds were the Grand Junction Chamber of Commerce, the Civilian Works Administration, the Emergency Conservation Works, the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, the National Park Service Emergency Roads and Trails, and regular National Park Service appropriations. [333] The road project was constructed in sections. Each camp worked on different sections, which were built as funding became available. Between July 1932 and July 1937, the sum of $528,772.27 was allotted for the construction of Rim Rock Road. Construction included rough grading of sections 1A, 1B, 1C, and 1D, as well as completion of two tunnels on the park's western end. [334] By July 1937, approximately 20 gravel miles of the eventually 23-mile gravel road were completed. [335] Between September 1937 and April 1940, another $39,111.87 was allotted for construction. [336]

Laborers for the Rim Rock Road project represented federal and local labor sources. Along with the CCC, the WPA, the Public Works Administration (PWA), the Emergency Relief Administration (ERA), LEMs, and National Park camps contributed to numerous aspects of the road project. Each work group was responsible for different elements of construction and overall park development. [337] Construction and employment possibilities were contingent on the availability of funds. When funding ran out, projects were temporarily stopped and layoffs occurred. Monthly totals of men at work in the park indicated the precarious nature of employment on the project. In December 1933, for instance, there was a total of 689 men working, but in January 1934, 814 men were accounted for. [338] These monthly totals varied markedly between 1933 and 1942. Construction was also disrupted by CCC enrollment periods, which generally lasted six months before new enrollees replaced those who were dismissed.

|

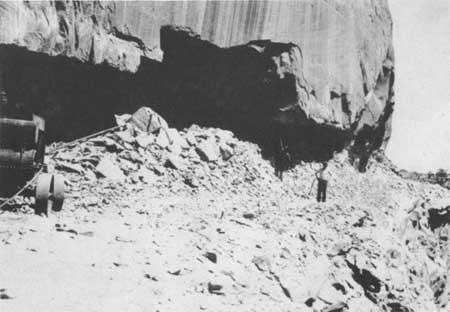

| Figure 4.2. CCC camp NM-1-C at present site of Monument Canyon Trail parking area. Colorado National Monument Museum and Archive Collection. |

|

| Figure 4.3. Portion of group photo of CCC enrollees and army personnel at Colorado National Monument. Colorado National Monument Museum and Archive Collection. |

The Road Project and the Community

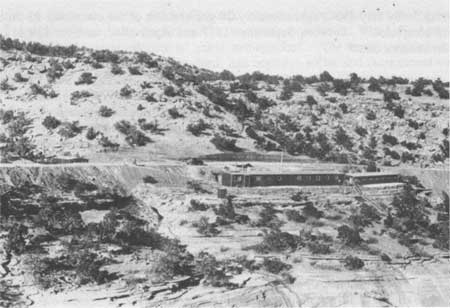

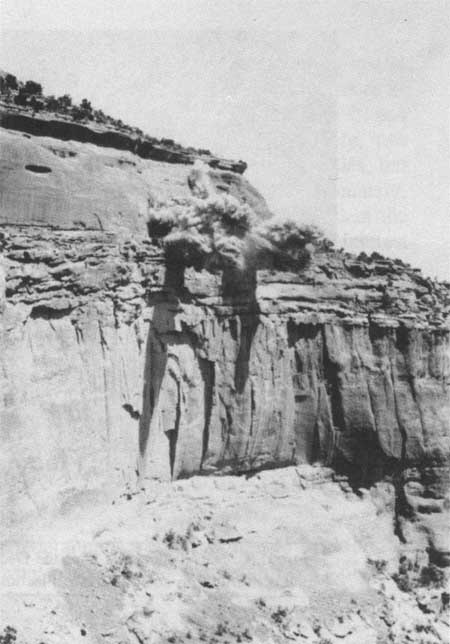

Community support of the road project was challenged on December 12, 1933, when the so-called "half-tunnel accident" took place. On that day, 20 Glade Park men recently hired by the CWA worked to cut part of the road into a cliff face in the shape of a half-tunnel. They had been blasting small sections of rock and then clearing by hand the debris from under the newly formed overhang of rock. Newspaper accounts stated that after the final shots were fired, supervisors of the project made the men wait 20 minutes before they went in to clear rocks. The men were working in what appeared to be a safe area when a powder charge fired by another work group on the opposite side of the canyon supposedly dislodged the cliff. [339] Three men actually jumped over the 300-foot cliff to escape, six men were instantly crushed, and one man was partially buried, living only through that night. The victims ranged in age from 19 to 60 years. [340]

The tragedy immediately raised a host of questions regarding the safety of workers and the competency of supervisors. The morning after the incident, the coroner arranged an inquest in which witnesses to the event testified. After all the testimony was heard, officials concluded that what had occurred had been an unavoidable accident [341] Yet, only three days after the accident, about thirty workers from the road project circulated a petition for a grand jury investigation and informed the District Attorney, William F. Haywood, that proper precautions for worker safety had not been taken prior to the accident or at any other time during the road construction. The workers also submitted statements to the Daily Sentinel that openly stated that not enough time had elapsed between the final blast and when the men continued work, and that the entire cliff face had not been investigated properly before the accident. [342] Finally on December 18, the same delegation of workers insisted on holding a public hearing at which the Chamber of Commerce, T.W. Secrest, and William Haywood were present. Most of the men agreed that the supervisors and foremen were blameless as far as the accident was concerned, although they unanimously stated that the chief powder man (explosives expert), Mr. McEwan, had not always been careful in his work. [343]

|

| Figure 4.4. View from cliff above the south portal of tunnel #3 (bottom right) and east side road and switchbacks. Colorado National Monument Museum and Archive Collection. |

|

| Figure 4.5. Men working at Cold Shivers Point on east Rim Rock Drive. Most of the work on the road was done by hand. Colorado National Monument Museum and Archive Collection. |

|

| Figure 4.6. Blasting at Half-Tunnel site (not actual accident blast). Colorado National Monument Museum and Archive Collection. |

|

| Figure 4.7. Blasting at Half-Tunnel site (not actual accident blast). Colorado National Monument and Archive Collection. |

|

| Figure 4.8. Half-Tunnel site after the December 12, 1933 accident. Colorado National Monument Museum and Archive Collection. |

In the meantime, Congressman Taylor received a telegram on December 15 from Robert N. Moreland, the father of one of the accident victims. Moreland requested another investigation, which Taylor assured him had been ordered by the Park Service. [344] E.B. Rogers, then superintendent of Rocky Mountain National Park, carried out the second investigation. On December 21, he met with local officials, including the chamber of commerce, the district attorney, the county certifying officer for CWA, and workers in the park. He concluded that the community generally agreed that the accident was unavoidable and that local residents still had faith in Secrest's abilities as supervisor of the road project. The workmen, however, were critical of W. Liddle, the foreman in charge of the workers involved in the accident, and C. E. McEwan, the explosives foreman. Finally, Rogers concluded that the controversy about the accident had been needlessly kept alive by people who were not directly involved in the incident, and that for the most part, the situation was finally settling down. [345]

The Half-Tunnel accident established a lasting connection between the road project and surrounding communities. Because only local men were killed, the accident was an especially sensitive issue. Nevertheless, the accident indicated that local interest in the park was still strong, and that the Park Service considered community support of the road project necessary. Congressman Taylor's intervention on behalf of Robert Moreland, which resulted in a second investigation, was a sign that public support of the road project was considered important to higher level officials. In the second investigation, E.B. Rogers emphasized the importance of community opinion as well. While his report included interviews with workmen, it was primarily an effort to measure the community's support of the road project. Finally, two editorials appearing in the Daily Sentinel expressed sympathy toward the victims' families, but also highlighted the road project's economic importance to the Grand Valley. [346] Ultimately, the Half-Tunnel accident was another example of the role that the community played in the Colorado National Monument's development. Because of nine local deaths and years of interest and money invested in the park, the people were naturally affected by the first major fatality on the road project. As the years passed, however, and Park Service road policy changed, many local residents pointed to the half-tunnel to indicate the sacrifice the community made for the road.

The availability of labor was an important gauge of local perceptions of the road project as well. Local employment levels varied. The original rosters for CCC camps 824 and 825 reveal that the majority of workers were from outside Colorado. The National Park Service was allowed to employ a certain percentage of LEMs, whose principal task was to train new enrollees. In 1934, restrictions were relaxed on the amount of LEMs hired. [347] Local men were also hired by relief groups other than the CCC. In December 1933, for instance, 50 unemployed men from Glade Park were hired by a federal civil works program to work on the road project. [348] Nevertheless, it is not clear just what percentage of workers in the Colorado National Monument was from the local area.

The community often panicked when projects were temporarily stopped due to lack of finding. Throughout the years of heavy construction, layoffs were common. In January 1934, for instance, there were 816 unemployed with 2100 dependents in Mesa County. The labor bureau urged the park to hire more workers despite already filled quotas. The park certainly could have used more labor but was not able to enroll any more men. [349] In March 1935, the closing of a Public Works project in the park put 165 men out of work. When families poured into the area from the dust-ravaged areas in Kansas and Nebraska, the already critical unemployment situation in the Grand Valley worsened. [350] The temporary closing of a CCC camp and a PWA camp in April 1935 prompted daily inquiries from local men seeking employment. Eventually 26 former employees of the camps went to the local relief office to convince officials to continue funding for the projects. [351] It is not clear if this appeal was successful, but it indicates that the local economic situation was such that the community relied upon the road project.

Roosevelt's attempt to make a permanent agency of the ECW in 1935 resulted in the closure of camps and reduction of enrollees in the Colorado National Monument and other parks. In September 1935, Roosevelt instructed ECW director Robert Fechner to reduce the ECW from its peak enrollment of 600,000 to 300,000 men by June 1936. In May 1936, he instructed the National Park Service to reduce its state and National Park camps by 20, and the number of enrollees per camp from 200 to 160. [352] Enrollment levels in CCC camps at Colorado National Monument averaged 160 as early as March 1936, and the custodian reported that "work projects suffered, because of the low company strength." [353]

Roosevelt continued his push for a smaller, permanent agency in January 1937 when he presented his annual budget message to Congress. He eventually hoped to decrease the ECW to 300,000 men and war veterans, 10,000 Native Americans, and 7,000 from U.S. territories. Congressional input was necessary because the ECW had only been authorized until June 1937. Roosevelt again pitched for a permanent agency in March 1937; under this plan the CCC would be an independent agency, new employees would be subject to Civil Service guidelines, and enrollees would be between the ages of 17 and 23 with evidence of proven need. Instead of creating a permanent agency, however, Congress passed a bill in which the ECW officially became the CCC and was extended until 1940. Despite the obvious changes in his plans for the CCC, Roosevelt signed the bill. [354]

This bill signaled a turning point for the CCC. Cuts in the program continued through 1937 and 1938. As more camps closed, officials in Washington received complaints from park superintendents who felt that certain projects and necessary park functions were interrupted and postponed. A measure to stabilize the CCC passed both the House and the Senate in 1938. In an effort to prevent the closure of 300 camps, $50 million was allotted to work relief programs. In addition, the number of National Park camps increased to 77 and state programs increased to 245. [355] Even after this effort, the CCC increasingly lost its effectiveness. By the time the U.S. entered World War II, its termination was inevitable.

|

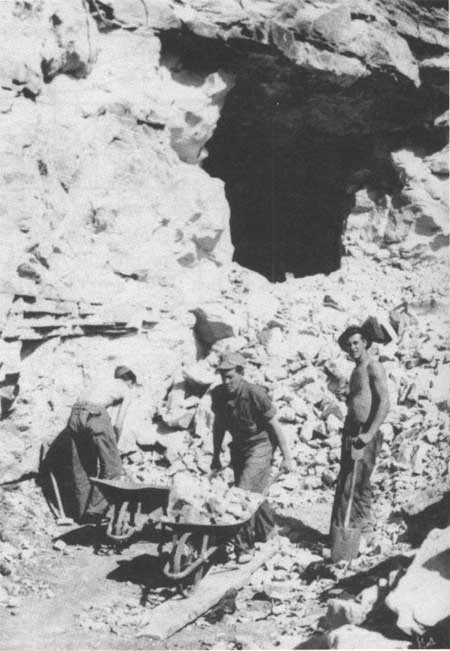

| Figure 4.10. Workers remove blast rubble from coyote hole or pilot bore in one of the road's three tunnels. Colorado National Monument Museum and Archive Collection. |

|

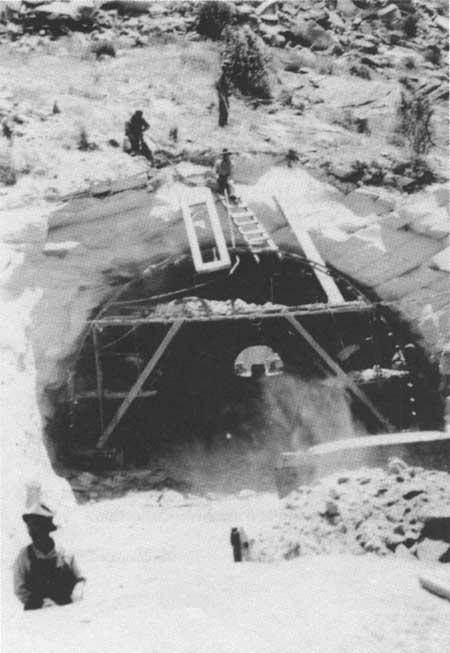

| Figure 4.11. North portal of tunnel #3 on east Rim Rock Drive. Colorado National Monument Museum and Archive Collection. |

Despite the uncertainty of the CCC's future, work camps in the Colorado National Monument accomplished a great deal. The years from 1937 to 1942 reflected not only the problems associated with labor cuts, but also the effectiveness that the work camps were capable of displaying. By June 7, 1937, 20 miles of Rim Rock Drive, including two tunnels, were opened for visitor use. [356] Numerous other projects were completed as well. The work camps built visitor facilities, an employee residence, and planned an administration area. Acting custodian Jesse Nusbaum commented in his monthly report for the park that "Colorado National Monument is beginning to shape up and looks more like a monument should. There is a far better spirit of cooperation between all agencies working on the Monument." [357]

Nevertheless, once the attack on Pearl Harbor occurred on December 7, 1941, work strength in the CCC decreased as national defense needs increased. In February 1942, all CCC projects were terminated but were picked up by the WPA until June 1942, when construction in the camp ended. Even the custodian and rangers at the park were called to active duty. [358]

Administration of Colorado National Monument,

1933-1942

Throughout the construction years, shifts in the management of Colorado National Monument significantly influenced local opinion of the Park Service and local use of the park. For the first time in its history, the Monument was supervised by superintendents, each of whom had his agenda for the park and his own idea of how to implement regulations. As each superintendent instituted more stringent regulations, local residents acquired the classic symptoms of Westerners who reject federal control as much as they rely upon it. At the same time that local residents accepted the employment supplied by the road project, they resented the government's control of the road once it was completed.

On November 14, 1933, Clifford Anderson arrived from Yellowstone to assume custodial responsibilities at Colorado National Monument. He immediately met with the secretary of the chamber of commerce W.M. Wood for a briefing on the park. [359] One of his first objectives was to educate the local populous about proper behavior in the park. He noted to National Park Service Director Arno Cammerer that in the past the Monument had been "abused terribly" and that he did not believe "people realize what these natural features mean to us and our future generations." [360] One of the worst problems was name-carving in the sandstone around the Devils Kitchen picnic area and Cold Shivers Point. To prevent further damage, Anderson planned to put up a boundary line sign, warning against "disfiguring or defacing" park property. He also worked to prevent rampant wood hauling from the park by commencing daily patrols. [361]

Anderson initiated many changes during his short time as custodian of the Colorado National Monument. Many of his policies conformed to the Park Service mission but were also shaped by local conditions and activities taking place in the park. His decision to restrict visitor access to the park was a response to heavy construction on Rim Rock Road. The section of road in Fruita Canyon involved some of the heaviest construction on Rim Rock Drive and was also a magnet for curious visitors eager for a glimpse of the work being done there. On February 18, 1934, there were over 600 visitors watching as charges of powder blasted the walls of the canyon. [362] By June 1934, Anderson's fears that the presence of tourists endangered both visitors and workmen had compelled him to restrict visitor access to the park. He also decided to install a box to register visitors. [363]

Anderson's custodianship exemplified a new level of Park Service presence in the Colorado National Monument. In addition to his campaign against vandalism and his efforts to monitor visitation of the park, he also conducted daily inspections of work projects in the park and maintained relations with the chamber of commerce. By August 1934, the Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Monument was placed under the jurisdiction of Colorado National Monument. Anderson began periodic inspection trips there as well. In June 1935, his idea for a registration box was expanded into a checking station, by which he hoped to provide information for visitors in addition to checking levels of visitation. He placed two iron pipe gates "to control travel from entering from Glade Park and Cold Shivers during the nights." [364] He was determined to control local access to the Park during construction and probably planned to extend this policy once the road was completed.

Anderson's departure from the Colorado National Monument in July 1935 resulted from an administrative conflict that arose between himself, Secrest, and the landscape architects over the construction of the road. [365] According to Secrest, Anderson had become too involved in the engineering of the road for which he had no experience or qualifications. When he was appointed custodian, he was expected to carry on relations with local organizations and attend to the overall protection of the park. Secrest was responsible for road, construction and supervision. Although the two men maintained a cooperative relationship, Secrest commented that "it was unfortunate and unfair for both Mr. Anderson and the Government that a policy exists whereby authority and control of expensive Government works are vested in an administrative head as such, regardless of the experience or ability. Mr. Anderson cannot be blamed too severely—he was a victim." [366] Anderson felt that, in light of this conflict, his services would be of greater use in another park. He left the Colorado National Monument on good terms with the community and with Secrest. [367] Secrest was designated acting custodian until a replacement was selected. [368]

In August 1935, Mesa Verde National Park assumed authority of the Colorado National Monument and the Black Canyon of the Gunnison. Ernest P. Leavitt became acting superintendent of the Monument and Black Canyon on August 13. [369] On October 4, 1935, Paul R. Franke, Assistant Park Naturalist at Mesa Verde, assumed Leavitt's duties as acting superintendent. [370] During that same month, Park Service officials decided to "kill all plans for a permanent ranger or custodian at this time," and to "continue having the superintendent of Mesa Verde in charge as acting custodian." They felt that, because vandalism had not worsened since Otto's days, a resident custodian was unnecessary. Furthermore, the road project was the first priority: "the big job is to push the road ahead with all force." [371]

In May 1936, the Grand Junction Chamber of Commerce expressed its displeasure with this decision, once again illustrating that it still affected Park Service policy to a certain degree:

There is no relation between Mesa Verde and the Colorado National Monument, nor has the Superintendent the least interest in or conception of how a project should be carried on. [372]

The National Park Service considered the chamber's opinions, but eventually decided it was best to have a permanent national park superintendent in charge of the Monument as Secrest was only a temporary ECW employee. [373] As late as December 1937, however, the Mesa County Commissioners adopted and passed a resolution in which they stated that, because of the differences between Colorado National Monument and Mesa Verde, the "joint administration" of the parks was "incompatible with the best interest, proper development, and fullest utilization of Colorado National Monument in which the people of Grand Junction and the surrounding territory are vitally interested ... ." [374] A copy of the resolution sent to Congressman Taylor indicated the local community's continuing proprietary attitude about the park; they requested that a separate administration and custodian be acquired for Colorado National Monument for the sake of the "large public investment." [375]

In early 1936, the management of Colorado National Monument shifted once again as Jesse Nusbaum, superintendent of Mesa Verde, became the acting superintendent of the Monument. At first, administration under Mesa Verde consisted of a series of bi-monthly inspections by the acting superintendent. Usually the inspections lasted a day or more and then the acting superintendent returned to Mesa Verde. For the most part, the acting superintendent umpired the relationship between the various federal agencies working on the road and the local community. Many of Nusbaum's policies, like those of his predecessor, were shaped by local conditions. He realized that due to the diversity of work camps in the park an interruption in the work program would endanger at least 600 jobs. To prevent such an event, he devised a plan that included the following: improvement of worker morale, definition of community needs, transfer of a resident ranger, and pushing the work so that more visitors could access the park. He transferred all Colorado National Monument funding, fiscal, and accounting records to Mesa Verde National Park as well. [376]

In September 1937, a resident ranger, James Luther, arrived at Colorado National Monument to serve as the "resident representative" for Mesa Verde. [377] Luther came to the Monument at the same time that Rim Rock Drive opened for visitor use. The road opening changed ranger duties markedly. Previously, visitors were limited by heavy construction, but by 1937 they were able to access most of the park. Increased access created new challenges. Although two CCC enrollees registered visitors at the checking station and two enrollees guarded the entrances, it was difficult to monitor visitor activity once they entered the park. Attempts were made to stop picnickers from driving off the road. By October 1937, 25-mile speed limit signs were placed at each entrance of the park. Actual tests concluded that this was the safest speed by which one could drive the road. Stop signs were also placed at the checking station. [378]

Other regulatory measures were taken as well. An entrance sign was placed at the Glade Park boundary, caution signs were put up on the Fruita Canyon road and larger boundary signs were placed at the four entrances to the Monument in the hope that wood-hauling, firearm use, grazing and hunting would be discouraged. [379] It was evident after the anniversary of the road's opening that local use presented more problems than regular tourist use:

Most of the March travel was local travel, either Grand Junction people out for an afternoon drive or Glade Park residents traveling back and forth to town. This local travel does a great deal of damage to the road in negotiating it during muddy or wet conditions. This condition will be removed when the road is hard surfaced. And the hauling of coal and other heavy supplies over the road by residents of Glade Park area cuts ruts badly during wet weather. One entrance to the Glade Park area certainly ought to be eliminated; and this would save many hundreds of dollars annually in road maintenance. [380]

In July 1938, seventy-five to eighty people were stopped for speeding; Luther reported that "the worst trouble is still with the local people, especially the residents adjacent to the Glade Park store." [381] He felt that educating local residents was the key to preventing abuse of the park and National Park Service regulations [382]

Despite Luther's efforts, there were still elements of the local population who disregarded Park Service regulations. In April 1938, for instance, sheep herds were ordered off both the Fruita Canyon road (the old Dugway) and the Serpents Trail. When confronted with this, sheepmen responded that they had used these roads for 30 years. [383] By 1940, a "consistent, determined effort" was made to eliminate the running of stock across the Monument. Monument officials worked with the Grazing Service to prevent further problems with stockmen. Nevertheless, on several occasions throughout the year, fines were assessed for breaking park regulations and for violating "trail permits" issued by the Grazing Service. [384] The attitude of local ranchers had not changed much since Otto's custodianship. As a result, it was difficult for current superintendents to implement new rules. Inefficiencies in early park management allowed many violations to go unchecked, so that when new regulations were enforced, local ranchers simply reverted to their old ways.

The Monument under James Luther's superintendency experienced many challenges to Park Service regulations. The major source of these challenges involved the newly opened Rim Rock Drive, and the use of the park by local residents. Before he left the Monument near the end of 1940, Luther initiated regular patrols of the road. In March 1940 alone, 19 patrol trips were made over the Rim Rock Drive. [385] Fee collection also became an issue during Luther's custodianship. On May 12, 1939, he used enrollees to collect fees from "cars, trailers, and motorcycles" who passed through headquarters 7 A.M. to 9 P.M. daily. Luther was instructed to pass without charge anyone he knew to be a resident of the Glade Park-Pinyon Mesa region whose sole access to their homes was over the Rim Rock Drive. The same policy was afforded Grand Valley residents with farming or stock interests in Glade Park. [386] At that time, preferential treatment of local residents seemed the best way to balance fee collection for park use and residential traffic to Glade Park via Rim Rock Drive. In an effort to maintain good relations or just for the sake of convenience, Luther implemented an open-ended fee policy that was bound to create conflicts once the population of that region became too large for park officials to recognize. Luther's efforts to maintain a cooperative relationship with local residents extended into other areas as well. He even attended the monthly Mesa County Coordinating Committee meetings in order to keep abreast of community activities and needs. [387]

Between 1941 and 1942, the Monument underwent yet another series of administrative changes. In January 1941, the new custodian, ranger Breyton Finch, arrived at the park to replace Luther. Like Luther, Finch was conscientious of local opinion. He not only attended meetings of the Mesa County Coordinating Committee, he went to the Piñon Mesa Stockgrowers' Association meeting to discuss realignment of existing stock drives in the park. Unlike Luther, however, Finch had some assistance in his work. Another ranger, Charles F. Smith, transferred to the park in March of that year. [388] In April 1941, ranger Homer Carson came to the Monument. For a while everything ran more smoothly than it had in years. Work on construction accelerated, the road was prepared for oiling, and the additional rangers alleviated many of the stresses of park management. [389]

The United States' entrance into World War II in December 1941 necessarily interrupted both the construction of the road and the administration of the park. CCC Camp strength weakened as enrollees enlisted for active duty, and eventually all construction ended in the park. The checking station closed and fee collection ended in November 1941. Eventually, Park Service personnel were called to active duty. Ranger Charles E. Smith left for military service, and even though new rangers replaced him, park activities were at an all-time low. [390]

The Postwar Years

The postwar years were characterized by a revitalization of the Colorado National Monument. Park activities abandoned during the war resumed; the checking station reopened in June 1946, and road maintenance once more became a priority. [391] At the same time, some of the older CCC buildings were removed and restoration of those areas commenced. [392] The most noticeable change was increased tourism. In March 1946, custodian Finch reported a 151 percent increase in the travel year to date, and in August 1946, a 785 percent increase was noted. [393] These phenomenal increases, however, were the source of conflict between rangers and visitors. One of the largest problems was that there were far more visitors than the limited personnel at the Monument could monitor. In 1946, it was estimated that about 75 percent of the visitor travel never reached the checking stations, which were located 4 miles from the Fruita entrance and 18 miles from the Grand Junction entrance to the park. There were no actual entrance stations in the park at this time. Most visitors entered and used the park without making contact with a ranger who could explain park regulations. Consequently, visitors' dogs ran leashless and people removed rocks, flowers, trees and other objects. Night travel became popular as people realized what a spectacular view of the Grand Valley the Monument afforded. Use of the park at night increased the probability of campfires in restricted areas. With rangers only able to make two complete loops of the park in an eight-hour period, much of the park was left unprotected. [394]

Local violations of park regulations during these years were prevalent. When local stockmen learned that Monument personnel were going to relocate their stock drives outside the park boundary, they were prepared to resist. Stock had originally been driven over the old Fruita Dugway and the Serpents Trail from Glade Park and Pinyon Mesa. When the Serpents Trail became part of the Rim Rock Drive, and the Dugway was obliterated during road construction, stockmen were without a road. The park's expansion in 1933 further exacerbated the situation because the proclamation made both access roads to Glade Park and Pinyon Mesa a part of the park. Eventually, an alternate road through the south end of No Thoroughfare Canyon was provided, but it was long, and often stock was held there overnight. Even though there was no water on this route, stockmen seemed temporarily satisfied. When park personnel suggested a road outside the park, a conflict arose. Although this plan was halted, both park officials and stockmen were left with unfavorable circumstances. Containing all the elements of a western conflict over land use, the situation included Park officials who did not want a permanent stock driveway through their Monument, and stockmen who wanted their old stock drives back. [395] For the time being, the situation remained static.

A relationship that was bound to become volatile was that between the Park Service and residents of the Glade Park region. The stock drive problem, and heavy trucking on Rim Rock Drive by landowners in Glade Park and Pinyon Mesa were issues that needed to be resolved. In spite of Park Service regulations to the contrary, marketable stock and wood were hauled over Rim Rock Drive by Glade Park residents. Both the county and the Forest Service used the road to haul heavy equipment from Pinyon Mesa, and by 1946, there was a rumor that a mining company planned to start a copper mine and haul ore from the Glade Park region. Park officials maintained that engineers never designed the road for this type of use. [396] Ironically, while many Glade Park residents began to resent the Park Service, many had also benefitted a great deal from the employment opportunities provided by the road project.

Despite some conflict, local initiatives also helped the park. A new road between Fruita and Grand Junction in June 1948 decreased the distance from Monument headquarters to Grand Junction from 23 to roughly 17 miles. Additionally, the town of Fruita and the State Highway Department put up new signs near the approach roads to the park. [397] Throughout road construction, Mesa County had improved approach roads to the park. During the postwar years, however, the county was often hired to maintain Rim Rock Drive. After the Park Service purchased the oil, the Mesa County Road Department applied it to the Rim Rock Drive in May 1948. [398]

While Mesa Verde still maintained its authority, Colorado National Monument personnel began to develop their own understanding of the Park Service and their duties. Breyton Finch was custodian of the park until February 1949, at which time the two rangers on duty took over that responsibility. In April 1949, Russell Mahan became superintendent. Mahan continued the important job of maintaining good relations with the community by attending Rotary Club meetings in both Grand Junction and Fruita. [399] The idea of "interpretive services" in which rangers kept track of the number of "contacts"—questions or discussions—they had with visitors or local residents, began during the postwar administration as well. "Contacts" also constituted speeches or meetings with local organizations. As always, the local factor played a role in Park Service activity on the Colorado National Monument. [400]

By 1950, the Colorado National Monument had entered a new phase in both its development as a tourist attraction and its relationship with the community. The cooperative relationship between the National Park Service and the communities adjacent to the Colorado National Monument was tested by Park Service attempts to regulate use of Monument facilities. After the road construction, the National Park Service controlled all aspects of park management. While the Park Service still recognized the importance of community support, it found that local use of the park accounted for most of the park's problems. Many of these difficulties resulted from the opening of Rim Rock Drive, but many of them, such as the stock driveways, had been developing since the park was set aside in 1911. Unlike the Otto years, however, the postwar years reflected far more use of the park by tourists and by local residents for recreational and nonrecreational uses. Relations with the local community were no longer as simple to define. Whereas it had once been important to keep the Grand Junction Chamber of Commerce and other local business groups happy, by 1950, the protection of the Colorado National Monument had become the first priority.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

colm/adhi/chap4.htm

Last Updated: 09-Feb-2005