|

Congaree National Park South Carolina |

|

NPS photo | |

A Last Stand for Floodplain Forests

Along the meandering Congaree and Wateree rivers rests Congaree National Park, a world of primeval forest, champion trees, diverse plant and animal life, and tranquility. This park protects over 25,000 acres of old-growth bottomland hardwood forest, the largest such area left in the United States. Congaree's bottomland forest is a wetland system of the Congaree and Wateree rivers. Because the park experiences wet and dry periods as the rivers flood and recede with seasonal rains, the vitality of the park's forest ecosystem depends on the good health of the rivers.

Until the late 1800s huge expanses of floodplain forests enriched the southeastern United States—with over one million acres in South Carolina alone. In the 1880s the lumber industry began harvesting these forests. Many remnants that survived the ax and plow were drowned by reservoirs. In less than 50 years most of these great bottomland forests were destroyed.

Congaree's trees escaped large-scale cutting because logging was especially hard here. Francis Beidler, whose lumber company owned bottomland forests in South Carolina, decided to leave the Congaree forest alone. Logging along the Congaree River ceased in 1914. In the 1950s conservationist Harry Hampton recognized the Congaree forest was one of the few remaining ecosystems of its kind and began efforts to protect it. Two decades later; when logging again threatened the area's giant trees, a public campaign led to establishing Congaree Swamp National Monument in 1976. In the following decades, the park was expanded and thousands of acres were designated as wilderness. In 2003 it became Congaree National Park. Today the park is a sanctuary for plants and animals, a research site for scientists, and a peaceful place for you to explore a forest of towering trees and diverse wildlife.

River, Floodplain. and Forest

Home of Champions

Congaree National Park is known for its unusual array of giant trees that hold the record for size of their species, including loblolly pines, hickories, and bald cypress. Both the canopies and understories of the park's forest harbor these giants. Their growth depends on the floodwaters of the Congaree and Wateree rivers.

Floods are essential to the park's entire wetland ecosystem because they deposit rich soils whose nutrients support the parkt complex plant communities. They occur when heavy rains fall within the Congaree and Wateree river watersheds. These watersheds drain over 14,000 square miles of northwestern South Caro!ina and western North Carolina. The park's wetlands depend on these upstream waters being healthy and clean.

Flooding typically occurs in the Congaree and Wateree river floodplain several times a year, usually in winter and early spring. The park's floodplain is relatively flat, with only a 2O-foot drop over 23 miles of river. Floodwaters enter the floodplain when the rivers overflow their natural banks and rise through breaks in the banks. In the floodplain the water courses through a network of creeks, sloughs, and guts; some of them are former riverbeds. Once these are filled, the water spreads across flat ground.

The forest is always changing. Windstorms and other natural disturbances are common in southeastern bottomland forests, altering the composition and character of these dynamic ecosystems. Impressive heights and shallow root systems make some of Congareet trees especially prone to toppling. When a large tree falls, its crown may leave a half-acre opening in the forest canopy, which allows sunlight to reach the forest floor. Vines and other sun-loving plants quickly occupy these openings. Slower growing, shade-tolerant plants emerge, block the sunlight, and eventually reclaim the open space. The downed trees, limbs, and logs on the forest floor provide homes to many animals and contribute to the variety of habitats and biodiversity.

Bald Cypress

Congaree National Park's forest is healthy and vigorous. Bald cypress trees

thrive here despite their strict requirements for seedling establishment and

growth. Because of their extensive root systems, bald cypress rarely blow down,

unlike oak and other hardwoods. The largest bald cypress in the park is over 27

feet in circumference. Buttressed bases and knees, which are part of the root

system, make this tree easy to identify. Knees over seven feet high have been

found here.

A Forest's Profile

Like most plant communities forests grow in layers. Attaining a height of over

155 feet, the forest profile at Congaree National Park reaches from the ground

to the top of a record-size loblolly pine. Variations in sunlight and moisture

create different microclimates amid the layers of forest. Wild grapevines and

poison ivy may climb into the forest canopy.

Floodplain Forests and Elevation

Changes of only a few feet in elevation cause differences in how long an area is

flooded and dramatic changes in soil conditions. These differences allow diverse

associations of tree species to grow in the floodplain. Sycamore, cottonwood,

and hackberry trees, whose roots tolerate periodic flooding, grow along stream

and river banks. Bald cypress and tupelo dominate low areas of standing water,

along with water ash and red maple. Overcup oak, laurel oak, and green ash are

abundant in better-drained flats. On drier soils, dense stands of cherrybark

oak, water oak, sweetgum, and holly thrive. Loblolly pines grow on slightly

higher ground.

Sweetgum and Mixed Hardwoods

This common association occurs throughout the floodplain. Sweetgums, along with

elm, swamp chestnut oak, laurel oak, water oak, green ash, and many other

hardwood trees, dominate the canopy. Ironwood, holly, and pawpaw are abundant in

the understory.

Floodplain Biodiversity

Congaree National Park ranks among the most diverse forest communities in North

America. It has over 20 different plant communities. Preliminary surveys have

found over 80 tree species, 170 bird species, 60 reptile and amphibian species,

and 49 fish species. These numbers will likely go up as surveys continue.

Cross-section of the Congaree River Floodplain

The topography of the Congaree River floodplain changes only slightly in

elevation. This profile sections the park on a line from high bluffs south of

the Congaree River to the visitor center on the lower northern bluff line. The

forest cover changes with slight changes in elevation and near the rivers and

Weston Lake.

Emergent Trees

Rising above the canopy, in the top layer of the forest, emergent trees spread

their crowns in full light. They get more light and air but less humidity than

the vegetation below. Organisms living in emergent trees differ from those in

the canopy layers.

High Canopy

Sweetgum, tupelo, elm, hackberry, and ash trees, along with several species of

oak and hickory, form the canopy. Summer sunlight cannot easily penetrate this

dense layer.

Sub-canopy

Red mulberry, American holly, red maple, and other trees grow here.

Understory and Forest Floor

Small trees like pawpaw and ironwood, shrubs like spicebush and strawberrybush,

and thickets of switch cane abound. Low-growing grasses and sedges dominate

scattered expanses of open understory.

Loblolly Pines

One loblolly pine over 15 feet in circumference and almost 170 feet tall ranks

among the park's champion trees. Loblollies here represent severa! age groups,

with many trees living hundreds of years.

The combination of loblolly pines with hardwoods is an uncommon forest association in floodplains. Past disturbances of normal forest succession patterns enabled the loblollies to gain a foothold. The exact cause and sequence of disturbances that encourage loblolly regeneration remain a mystery.

Exploring Congaree National Park

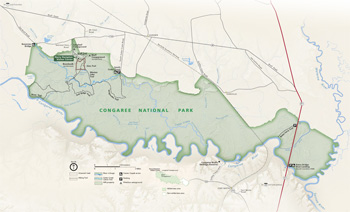

(click for larger map) |

Stop at the Harry Hampton Visitor Center for information and program schedule, exhibits, a park film, and a bookstore. The visitor center is open daily year-round, except Thanksgiving, December 25, and January 1.

If you are planning an overnight trip in the park, stop by the visitor center to obtain camping regulations, safety information, maps, and a free camping permit. Permits are granted for up to two weeks; the limit is 28 days in any six-month period. If you will be camping in the backcountry, bring a stove for cooking because fires are prohibited. If you are in the campground, you must use existing fire rings.

You may experience the park's natural wonders on land or water. The boardwalk loop provides wheelchair and stroller ac(ess to Weston Lake and foot access to other trails that wind through the floodplain. Colored blazes (markers) make the trails easy to follow. Free ranger-guided nature walks and canoe tours are available.

A marked canoe trail invites you to explore Cedar Creek in your own canoe or kayak. You can also rent canoes and other gear from a variety of outfitters in the Columbia, SC area. Before embarking on any boat trip in the park, be sure to check water levels online or by contacting park staff.

General Information

Safety and Regulations

• Pets must be leashed; they are allowed on all trails except

boardwalk.

• Be alert for poison ivy, stinging insects, snakes, and mosquitoes.

• Anglers must have a South Carolina fishing license. Minnows and fish eggs

are prohibited as bait. Fishing is not allowed in Weston Lake.

• Bicycles and motor vehicles are not permitted on trails.

• Littering, digging bait, picking plants, and disturbing wildlife are not

permitted.

• For firearms regulations, check the park website.

• Emergencies: call 911.

Accessibility

We strive to make our facilities, services, and programs accessible to all. Call

or check our website.

Getting to the Park

Congaree National Park is southeast of Columbia, 5C. From I-77 take exit 5 onto

SC 48 (Bluff Road). Follow the signs to the park.

Wilderness

Congress has designated most of the park for protection under the 1964

Wilderness Act. Bicycles and motorized vehicles and watercraft are not allowed

in wilderness. Wilderness protects forever the land's natural conditions,

opportunities for solitude and primitive recreation, and scientific,

educational, and historical values. For information visit www.wilderness.net.

Source: NPS Brochure (2012)

|

Establishment

Congaree National Park — November 10, 2003 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

A Place of Nature and Culture: The Founding of Congaree National Park, South Carolina (Elizabeth J. Almlie, extract from Federal History, Issue 3, ©Society for the History in the Federal Government, 2011)

Advertising and Social Media Strategy for America's National Parks: A Case Study of Congaree National Park (©Abigail Gallup, Thesis, South Carolina Honors College, December 2021)

An Archeological Survey of Congaree Swamp: Cultural Resources Inventory and Assessment of a Bottomland Environment in Central South Carolina Research Manuscript Series 163 (James L. Michie, University of South Carolina Institute of Archeology and Anthropology, July 1980)

Anuran Community Monitoring at Congaree National Park, 2011 NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS-2013/527 (Briana D. Smrekar, Michael W. Byrne, Marylou N. Moore and Aaron T. Pressnell, August 2013)

Anuran Community Monitoring at Congaree National Park, 2014 Data Summary NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS-2015/988 (Briana D. Smrekar and Michael W. Byrne, November 2015)

Assessment of Water Resources and Watershed Conditions in Congaree National Park, South Carolina NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SECN/NRR-2010/267 (Michael A. Mallin and Matthew R. McIver, December 2010)

Barriers to a Backyard National Park: Case Study of African American Communities in Columbia, SC NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/EQD/NRR-2012/604 (Yen Le, Nancy C. Holmes and Colleen Kulesza, December 2012)

Concentrations of metals in bed material in the area of Congaree Swamp National Monument and in water in Cedar Creek, Richland County, South Carolina USGS Open-File Report 90-370 (Theodore W. Cooney, 1990)

Congaree National Park: An Evolving Approach to Managing Nature and History in the National Park Service (©Jason Harris Aldridge, Master's Thesis University of Georgia, 2014)

Congaree Swamp: Greatest Unprotected Forest on the Continent (South Carolina Environmental Coalition, Sierra Club and Congaree Swamp National Preserve Association, c1975)

Congaree Swamp National Monument: An Administrative History (Francis T. Rametta, March 1991)

Deeply Rooted: The Story of Congaree National Park (Taylor Waters Karlin, Winter 2015)

Disturbance History and Establishment of Loblolly Pine in the Congaree Swamp Final Report (Neil Pederson and Robert H. Jones, August 24, 1994)

Final Management Plan for Non-native Wild Pigs within Congaree National Park (CONG) with Environmental Assessment (December 2014)

Foundation Document, Congaree National Park, South Carolina (October 2014)

Foundation Document Overview, Congaree National Park, South Carolina (November 2014)

General Management Plan, Congaree Swamp National Monument, South Carolina (December 1988)

General Management Plan, Wilderness Suitability Study & Environmental Assessment, Congaree Swamp National Monument, South Carolina (September 1987)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Congaree National Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2014/857 (J.P. Graham, October 2014)

Geomorphology of the Congaree River Floodplain: Implications for the Inundation Continuum (Haiqiug Xu, Raymond Torres, Shailesh van der Steeg and Enrica Viparelli, extract from Water Resources Research, Vol. 57, 2021)

Hydrology and Its Effects on Distribution of Vegetation in Congaree Swamp National Monument, South Carolina U.S. Geological Survey Water-Resources Investigations Report 85-4256 (Glenn G. Patterson, Gary K. Speiran and Benjamin H. Whetstone, 1985)

Identifying Values and Benefits of Congaree National Park (Maka Bitsadze, Master's thesis, 2013)

Impacts of Visitor Spending on the Local Economy: Congaree National Park, 2005 (Daniel J. Stynes, August 2007)

Junior Ranger Activity Booklet (Ages 6 and under), Congaree National Park (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Junior Ranger Activity Booklet (Ages 7-10), Congaree National Park (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Forms

Brady's Cattle Mound (Jill Hanson, 1996)

Bridge Abutments (Jill Hanson, 1996)

Cattle Mound #6 (Georgia Pacific Cattle Mound) (Jill Hanson, 1996)

Cook's Lake Cattle Mound (Jill Hanson, 1996)

Cooner's Cattle Mound (Jill Hanson, 1996)

Dead River Cattle Mound (Jill Hanson, 1996)

Historic Resources of Congaree Swamp National Monument (Jill Hanson, November 1, 1995)

Northwest Boundary Dike (Jill Hanson, 1996)

Southwest Boundary Dike (Jill Hanson, 1996)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment, Congaree National Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SECN/NRR-2018/1665 (JoAnn M. Burkholder, Elle H. Allen, Carol A. Kinder and Stacie Flood, June 2018)

Park Newspaper (Boardwalk Talk): Spring 2010 • Summer 2010 • Fall 2010 • Winter 2011 • Spring 2011 • Summer 2012

Preliminary report of findings of the contaminant assessment process for the Congaree Swamp National Monument (James Coyle, Patrick Anderson and Marcia Nelson, December 1997)

Species Diversity and Condition of the Fish Community During a Drought in Congaree National Park Final Report (L. Rose and J. Bulak, October 2005)

Specific Area Report, Proposed Congaree Swamp National Monument, South Carolina (April 1963)

Statement for Management, Basic Operations Statement: Congaree Swamp National Monument (1994)

Summary of Amphibian Community Monitoring at Congaree National Park, 2010 NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS-2011/167 (Michael W. Byrne, Briana D. Smrekar, Marylou N. Moore, Casey S. Harris and Brent A. Blankley, May 2011)

Vegetation Community Monitoring at Congaree National Park, 2010 NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS-2012/259 (Michael W. Byrne, Sarah L. Corbett and Joseph C. DeVivo, March 2012)

Vegetation Community Monitoring at Congaree National Park, 2014 Data Summary NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS-2016/1016 (Sarah Corbett Heath and Michael W. Byrne, May 2016)

Wadeable Stream Habitat Monitoring at Congaree National Park: 2018 Baseline Report NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SECN/NRR-2021/2264 (Christopher S. Cooper, Jacob M. Bateman McDonald and Eric N. Starkey, June 2021)

Water Resources Management Plan, Congaree Swamp National Monument (David B. Knowles, Mark M. Brinson, Richard A. Clark and Mark D. Flora, May 1996)

cong/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025