|

Coronado National Memorial Arizona |

|

NPS photo | |

Tracking the Coronado Expedition

Coronado National Memorial commemorates and interprets the Coronado expedition and the cultural conflict and exchange between indigenous peoples and Spaniards during the 1500s. The area offers panoramic views of the US-Mexico border and San Pedro River Valley—Coronado's probable route.

The Coronado Expedition and the "Seven Cities of Cíbola"

Early in the 1500s Spain established a colonial empire in the Americas. Gold from Peru to Mexico (New Spain) poured into Spain's treasury, and new lands opened for settlement. Beyond the frontier a few hundred miles north of Mexico City lay lands unknown to the Spaniards. Tales of riches there had ignited Spanish imaginations since Spain's arrival in the Americas, luring explorers like Hernán Cortés (Mexico, 1519), Pánfilo de Narváez (Florida, 1528), and Francisco Pizarro (Peru, 1531). A few successes kept alive the dream that great wealth was within reach, but many Spanish expeditions failed.

In 1536 the four survivors of the shipwrecked Narváez expedition, which included Cabeza de Vaca and enslaved African Estéban de Dorantes, arrived in Mexico City. After eight years of wandering in what is today Texas and northern Mexico, they spoke of "large cities, with streets lined with goldsmith shops, houses of many stories, and doorways studded with emeralds and turquoise!" Eager to know if these stories were true, the viceroy of New Spain Antonio de Mendoza sent Fray Marcos de Niza to explore the "Tierra Nueva" (New Land) in 1539. As a scout for Fray Marcos's party, Estéban learned many languages and was able to relay information to Fray Marcos about the people he would encounter. Estéban is known as the first person of African descent to visit this part of the world and was among the first from the Spanish explorations to make contact with these early peoples of America's Southwest. Though Fray Marcos returned with garbled, exaggerated reports, Mendoza believed he spoke the truth and chose Francisco Vásquez de Coronado to lead an expedition to the fabled "Seven Cities of Cibola."

Coronado had come to New Spain in 1535. His friendship with Mendoza and successful missions had won him prominence on the Mexico City council and, since 1538, as governor of the frontier province New Galicia. On January 6, 1540, Mendoza commissioned Coronado to be expedition commander and captain-general of all the lands he might discover and claim for king and country. Mendoza counseled Coronado that the purpose was missionary, not conquest. The expedition left Compostela on February 23, 1540, with over a thousand native allies, 350 Spaniards, many servants and enslaved people, and several priests, including Fray Marcos. Supplies went north by ship under Captain Hernando de Alarcón, but Alarcón and the supplies failed to reach Coronado. After arriving at Culiacán, Coronado and 100 soldiers marched ahead of the slower main army. On July 7, 1540, Coronado's group arrived at the pueblo Háwikuh—the first of the Cities of Cibola. Instead of a golden city, they found a crowded, rock-masonry village. After brief, unsuccessful negotiations the Spaniards attacked and forced the Zuni who lived there to leave. The pueblo, stocked with food, became Coronado's headquarters until November 1540. Fray Marcos, whose tales had misleadingly raised hopes of fortune, was sent back to Mexico City amid rising resentment.

At Háwikuh Coronado sent his captains to scout the region. Don Pedro de Tovar went to Hopi villages in today's northeastern Arizona. Garcia Löpez de Cárdenas reached the Grand Canyon of the Colorado. Hernando de Alvarado went east past Acoma and Tiguex pueblos to Cicuyé (Pecos) pueblo on the upper Pecos River. Here, the Spaniards encountered a Plains Indian they nicknamed the Turk "because he looked like one." The Turk astounded them with tales of a rich land to the east—Quivira—that renewed the Spaniards' hopes of wealth. But exploration had to wait until spring. The army wintered at Tiguex, where the Indians, at first friendly, grew hostile over the Spaniards' violations of hospitality and friendship. Battles followed; the Spaniards killed residents of one pueblo and forced others to abandon several pueblos.

On April 23, 1541, the army, guided by the Turk, set out for Quivira. After 40 days Coronado sent most of the men back to Tiguex then pressed on with 30 others. At Quivira they were again disillusioned—the villages were grass houses. After admitting the Quivira story was a Pueblo Indian plot to lure them onto the plains to die of starvation, the Turk was killed. Dreams of fame and fortune shattered, Coronado returned to Mexico City in spring 1542. Though discredited, he resumed governorship of New Galicia. He was called to account for his cruelty toward the American Indians during the expedition, but his name was eventually cleared. He died in 1554 at age 42. Rather than gold, the expedition brought back knowledge of the northern lands and its peoples and put further colonization within reach.

Plants The park is a cultural area in a natural setting of 4,750 acres of oak woodlands in southeast Arizona at the southern end of the Huachuca (wha-CHOO-ka) Mountains. The park preserves plants and animals that are native to the Southwest and typical of "sky islands" (mountains set above arid valleys). Desert grasses and shrubs grow at low elevations with honey mesquite and desert willow along short-lived drainages. Oak, pinyon pine, and alligator juniper forests dominate the upper canyon with Arizona sycamore and walnut along drainages. Other common plants are manzanita with its distinctive red bark, agave (century plant), Schott's yucca, sacahuista (beargrass), and sotol (desert spoon). Cacti include pincushion, rainbow, and prickly pear. Many plants, like prickly pear pads, pine nuts, manzanita berries, agave hearts, and yucca seeds, provide important food for wildlife.

Animals Commonly seen mammals at the park include gray fox (above), white-tailed deer, peccary (javelina), coatimundi with its long tail, and coyote. Also found here, but more elusive, are bobcat, black bear, and mountain lion. Well-known for rich birdlife, the park features over 140 recorded species, including 50 resident birds with different species sighted each season. Often seen are acorn woodpecker, Mexican jay, Montezuma quail, spotted towhee, white-winged dove, rufous-crowned sparrow, painted redstart, and many species of hummingbirds.

Visiting Coronado National Memorial

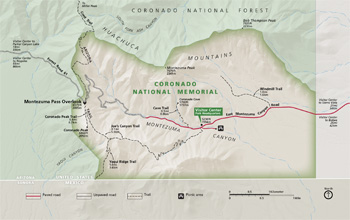

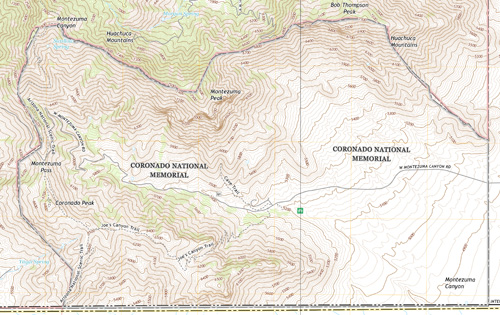

(click for larger maps) |

Driving and Hiking Routes At 6,575 feet, Montezuma Pass has sweeping views of San Pedro River Valley to the east and San Rafael Valley to the west. Caution! Vehicles over 24 feet are prohibited on the road up to the pass due to steep grades and tight switchbacks. Atop the pass is parking for hikers using park trails and connecting US Forest Service trails in the Huachuca Mountains. Cave Trail leads to the 600 foot long Coronado Cave. The entrance and cave are unimproved; access may be difficult. Hike the one-mile roundtrip path to explore this natural limestone feature. Windmill Trail follows an old two-track ranch road through the grasslands and visits an historic windmill and corral. This two-mile roundtrip trail is an excellent winter birding path. Yaqui Ridge Trail is the southern end of the 790-mile Arizona Trail that crosses the state from Mexico to Utah. At vistas along the trails, you can look toward the horizon and see country through which Coronado led his soldiers and missionaries.

Getting Here Take AZ 90 off I-10. Drive 25 miles south to Sierra Vista, then take AZ 92 16 miles to S. Coronado Memorial Dr. (joins AZ 92, 20 miles west of Bisbee). Near the park this road becomes E. Montezuma Canyon Rd., which is paved for a mile west of the visitor center then becomes a dirt-and-gravel mountain road up to Montezuma Pass. From there a dirt road continues west—a slow, scenic drive across San Rafael Valley and over the Patagonia Mountains to Nogales. The visitor center (elevation 5,230 feet) has a picnic area and nature trail. Camping is prohibited in the park but available in Coronado National Forest or at Parker Canyon Lake, 18 miles west in the Canelo Hills.

Weather Carry plenty of water when hiking. Protect yourself from the sun. Summers are hot with daytime temperatures in the 90s°F and low humidity. Winter temperatures often fall below freezing at night with daytime highs of 40-60°F. The rainy season runs late June to early September. Severe thunderstorms, lightning, and flash floods often accompany rain. Precipitation averages 20 inches a year.

Regulations Federal law protects all plants and animals in the park; do not gather, disturb, or destroy them. Hunting and wood gathering are prohibited. Pets are prohibited on all trails except Crest Trail (begins north of the Montezuma Pass parking area). For firearms regulations check the park website.

Safety Smuggling and/or illegal entry are common this close to the US-Mexico border. Be aware of your surroundings at all times. Do not travel alone in remote areas. Report suspicious behavior to a park ranger or border patrol agent.

Source: NPS Brochure (2017)

|

Establishment

Coronado National Memorial — November 8, 1952 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

A History of the State of Texas Mine, Coronado National Memorial (Joseph P. Sanchez, 2007; rev. Robert L. Spude, 2009, extract from Forgotten Pathways through Montezuma Canyon: Coronado National Memorial Historic Resources Study)

Acoustical Monitoring 2010, Coronado National Memorial NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRSS/NRR-2014/873 (Noah Schulz, Cynthia Lee and John MacDonald, November 2014)

Arizona Explorer Junior Ranger (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Between Two Countries: The Story Behind Coronado National Memorial (Joseph P. Sánchez, Bruce A. Érickson and Jerry L. Gurulé, 2001)

Coronado National Memorial Historical Research Project: Annotated Bibliography ()

Coronado National Memorial Historical Research Project: Research Topics (Joseph P. Sánchez and John Howard White, May 20, 2014)

Draft General Management Plan / Environmental Impact Statement, Coronado National Monument, Arizona (May 2003)

Final General Management Plan / Environmental Impact Statement, Coronado National Monument, Arizona (January 2004)

Finding Aid: Coronado Administrative Records, 1939-1989, Coronado National Memorial (August 2006)

Five Year Summary of Wildlife Camera Trap Monitoring across Three Parks: A systematic approach to monitoring wildlife NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/CHIR/NRR-2015/1069 (Amanda Selnick, Jason Mateljak and Thomas Athens, October 2015)

Foundation Document, Coronado National Memorial, Arizona (January 2016)

Foundation Document Overview, Coronado National Memorial, Arizona (January 2016)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Coronado National Memorial NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2011/438 (J. Graham, August 2011)

Junior Arizona Archeologist (2016; for reference purposes only)

Junior Ranger Guide, Coronado National Memoriale (2011; for reference purposes only)

Management Program: An Addendum to the Natural and Cultural Resources Management Plan for Coronado National Memorial (April 1977)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Historical Resources of Coronado National Memorial (Prehistoric Cochise Culture Sites) (Neal Ackerly and Keith Anderson, January 1978)

Natural and Cultural Resources Management Plan and Environmental Assessment for Coronado National Memorial, Arizona (April 1977)

Park Newspaper (The Explorers: A Visitor's Guide to the Southwest Arizona Parks): 2012 • 2017

Plant Ecology and Vegetation Mapping at Coronado National Memorial, Cochise County, Arizona Cooperative National Park Resources Studies Unit Technical Report No. 41 (George A. Ruffner and Robert A. Johnson, December 1991)

Springs, Seeps and Tinajas Monitoring Protocol: Chihuahuan and Sonoran Desert Networks NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SODN/NRR-2018/1796 (Cheryl McIntyre, Kirsten Gallo, Evan Gwilliam, J. Andrew Hubbard, Julie Christian, Kristen Bonebrake, Greg Goodrum, Megan Podolinsky, Laura Palacios, Benjamin Cooper and Mark Isley, November 2018)

Statement for Management: 1989, Coronado National Memorial (April 1989)

Status of Climate and Water Resources at Chiricahua National Monument, Coronado National Memorial, and Fort Bowie National Historic Site: Water Year 2019 NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SODN/NRR—2022/2378 (Kara Raymond, Laura Palacios, Andy Hubbard, Cheryl McIntyre and Evan Gwilliam, May 2022)

Stories of the Sky Islands: Exhibit Development Resource Guide for Biology and Geology at Chiricahua National Monument and Coronado National Memorial (Adam M. Hudson, J. Jesse Minor and Erin E. Posthumus, May 17, 2013)

Terrestrial Vegetation and Soils Monitoring in Coronado National Memorial, 2009-2010 NPS Natural Resource Data Summary NPS/SODN/NRDS-2011/215 (J. Andrew Hubbard, Sarah E. Studd and Cheryl L. McIntyre, December 2011)

The Coronado Expedition of 1540-1542: A Special History Report Prepared for the Coronado Trail Study (James E. Ivey, Diane Lee Rhodes and Joseph P. Sanchez, 1991)

Vegetation Inventory, Mapping, and Characterization Report, Coronado National Memorial NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/SODN/NRR-2018/1818 (Sarah E. Studd, Jeff Galvin and J. Andrew Hubbard, November 2018)

coro/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025