|

Fort Randall Reservoir Archeology, Geology, History |

|

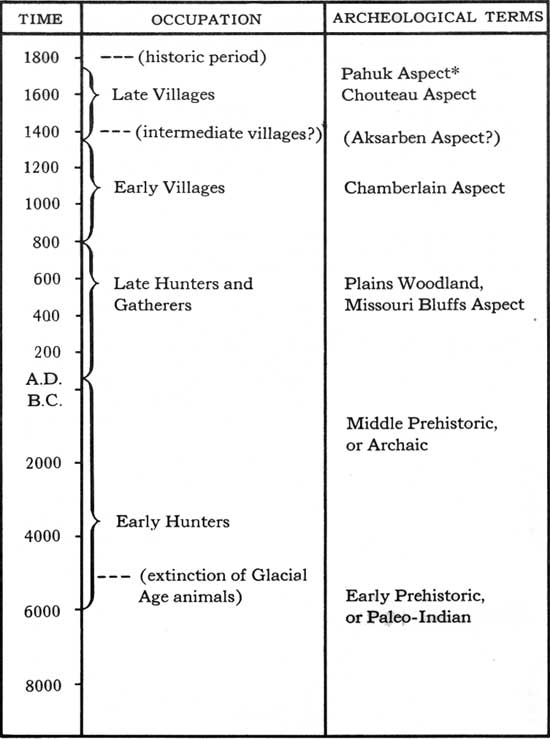

THE LATE VILLAGE PERIOD

The final, major period in the prehistoric occupation of the Fort Randall Reservoir is characterized by a continuation of the gardening-farming economy by Indians with new and distinctive forms of architecture, tools, and pottery.

From excavations at the Crow Creek and the Talking Crow Sites there is some indication that the Late and Early Village periods may have been separated by an interval during which peoples related to groups in present-day Nebraska moved into the area. So little is known of the character, extent, and intensity of this middle period, however, that it is not profitable to discuss it at present. It is also possible, and indeed probable, that the occupation of the Fort Randall area diminished during the drought years of the A.D. 1200's and early 1300's. (These prehistoric droughts have been discovered and dated by means of the study of the annual growth rings of ancient trees.)

There is very little evidence upon which to estimate the beginning of the Late Village Period, but an initial date at the end of the 1300's or during the 1400's seems reasonable at present.

Major excavations at the Spain, Talking Crow, Scalp Creek (late occupation) Oacoma, and Oldham Sites show that the economy and general way of life of the Late Village Indians was very similar to that of their predecessors. Similar kinds of tools were manufactured and used, probably to serve the same purposes. Differences can be observed, however, in the appearance of some new tool types and in specific details of manufacturing techniques and other characteristics.

|

| A bone awl, a bison scapula hoe, and a large stone knife from Late Village sites in the Fort Randall Reservoir. Photo — Missouri Basin Project, Smithsonian Institution |

|

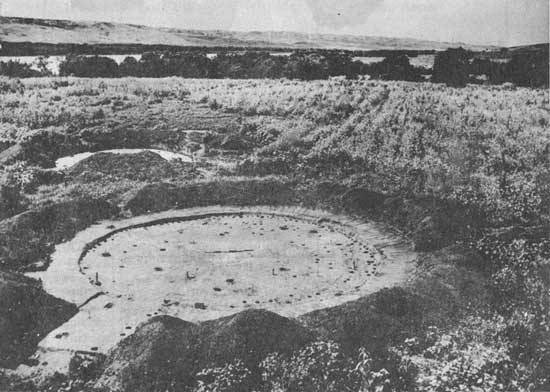

| Excavations in a Late Village site at Oacoma, near the upper end of The Fort Randall Reservoir. The Lodges are circular, with four inner roof supports and a central fire pit. The large structure (upper right) was probably used for ceremonial purposes. Photo — Missouri Basin Project, Smithsonian Institution |

Perhaps the most outstanding change occurred in the field of architecture. The long rectangular houses were replaced by circular ones. Without doubt, these were the progenitors of the well-known "earth lodge" that early explorers found among the Mandan, Arikara, Hidatsa, Pawnee, and other village tribes of the north and central plains.

The typical domestic earth lodge was a circular structure with a short passage-like entryway. A stout timber framework supported a thick covering of branches, grass and earth. Such a house might be more than 40 feet in diameter and 10 to 15 feet high. The principal roof supports, usually four in number and connected at the top by horizontal stringers, were placed around the central fire pit in a manner forming the four corners of a square. Wall posts, erected around the outer edge of the structure, also supported heavy horizontal stringers. Slanting rafters connected the central stringers and the outer wall line to complete the basic framework. The roof poles sometimes projected upward beyond the central beams and framed a small opening, or smoke-hole, at the top of the house. In other cases, a flat roof was built. The entire framework was then covered with branches, willows, grass, and earth. The resulting house was a truly weather-proof and massive structure.

Interior house features included a fireplace, beds along the wall, perhaps other simple furniture, and, frequently, one or more storage pits, ordinarily dug below the floor to depths of from three to five feet.

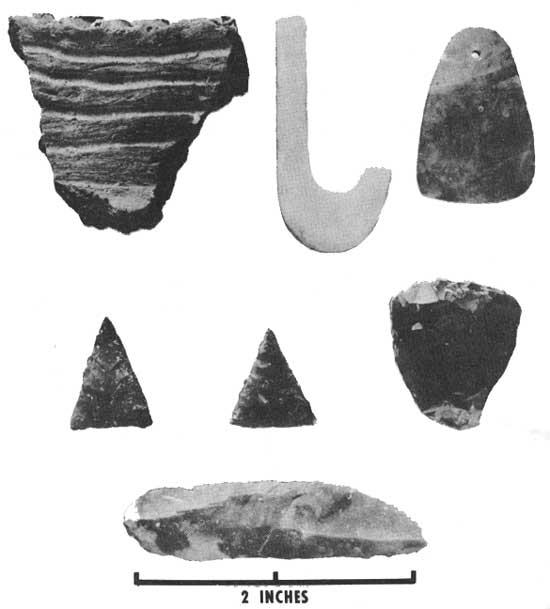

Several changes occurred in the manufacture and decoration of pottery. Although the new developments were not of such a nature as to indicate that pottery was being used for new or revolutionary purposes, they do aid the archeologist in identifying the general period to which an abandoned site belongs. Use of the grooved paddle for finishing vessel exteriors became practically universal throughout the area, and trailed and incised designs gained greatly in popularity.

|

| The excavation of a circular lodge at the Oldham Site. The firepit and two rear roof posts are not yet exposed. Photo — Missouri Basin Project, Smithsonian Institution |

Although it is difficult to judge accurately from the site samples available, it appears that the population density in the Fort Randall area increased somewhat during the late village period. Such an increase is known to have occurred in sections of the Missouri River Valley farther north, and it is during this late period that the Plains earth-lodge cultures reached their final development. There is some rather tentative evidence that the late Fort Randall villages actually represent the prehistoric culture of some of the Arikara and Pawnee groups.

|

| A decorated rim from a pottery vessel, a bone fishhook, a pendant, arrow points, a scraper, and a small blade from Late Village sites in The Fort Randall area. Photo — Missouri Basin Project, Smithsonian Institution |

It is of interest that, although items of European manufacture are occasionally found on the latest village sites in the Fort Randall area, Lewis and Clark observed no occupied villages in the region. This would indicate that the Fort Randall villages were abandoned at least by the late 18th Century, after which time only wandering bands of Sioux occupied the area.

SUMMARY OF THE HISTORIC AND PREH1STORIC OCCUPATIONS IN THE FORT RANDALL RESERVOIR AREA

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

sec8.htm

Last Updated: 08-Sep-2008