|

Lake Sharpe—Big Bend Dam Archeology, History, Geology> |

|

PREHISTORY IN THE BIG BEND RESERVOIR

Men have lived in the Great Plains for more than ten thousand years. Those who came first, the Paleo-Indian, as archeologists call them, were hunters of the mammoth and the giant bison. They were not the mounted hunters so well known from motion pictures and television; instead, they pursued the great herding animals of the end of the last ice age on foot, driving them into traps or spearing those that had become mired in bogs or waterholes. Horsemen did not appear on the Plains until the 18th century. They too were bison hunters but with a way of life that was strikingly different from that of the earlier hunters.

Archeologists know little about the early hunters within the limits of the Big Bend country. Several early sites have been found but only a few have been excavated. Perhaps the best known is the Medicine Crow Site near Fort Thompson at the lower end of Lake Sharpe. Here, the remains of an earth-lodge village, probably dating from the 18th century, was found overlying a series of deeper, older occupations. The evidence is not entirely clear but small groups of hunters must have camped here as early as the end of the glacial period.

Agricultural peoples did not appear in the northern and central Plains until about the time of Christ. While they too were hunters, they are assumed to have cultivated small plots of corn and probably other crops as well. The term Plains Woodland has been applied to these newcomers because they appear to have had a culture reminiscent of the widespread Woodland Tradition that flourished in the eastern United States.

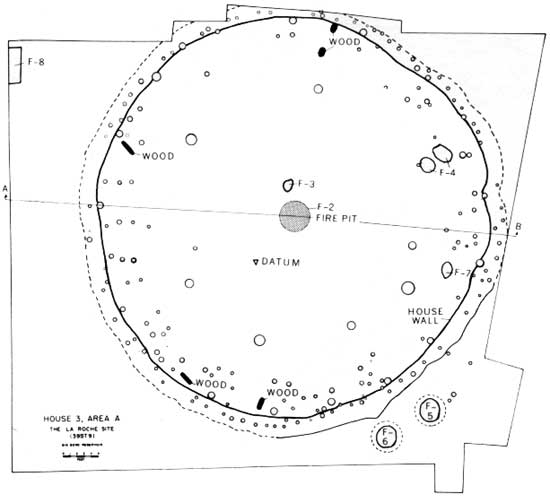

As was true with the early hunters, the Plains Woodland peoples were not numerous and their village or camp sites are scarce. Within the Big Bend area a few such sites are known, one of which now lies beneath the Big Bend Dam. Of the others, the La Roche Site in the central part of the reservoir, has been most enlightening. Like the Medicine Crow Site, the La Roche village contains several occupations or components. The earliest is representative of the Plains Woodland horizon and has provided good evidence of a distinctive house or lodge—something not previously discovered. The structure was oval in floor plan, with a row of large posts down the center (presumably to support a ridge pole) and numerous smaller posts around the margin. Probably the house was "loaf-shaped" and covered with bark, hides, and/or thatch.

The house was associated with typical Woodland artifacts, of which pottery is the most readily identified. In order to compact the clay, the surfaces of Woodland pottery vessels were beaten with a wooden paddle wrapped with cords of twisted sinew or fibre. The resulting surface, "cord-roughened" as it is termed, is characteristic of Woodland pottery and that of the following sedentary village period.

Other evidence of Woodland peoples is in the form of low dome-shaped mounds which were once common in the Fort Thompson area. A number have been excavated by the Smithsonian Institution and while there is variability, the pattern is essentially the same. Customarily, the mounds contain, the remains of primary and/or secondary burials with a scattering of artifacts. Similar sites extend well up the Missouri River into North Dakota; many others of a related pattern have been found in the once forested country to the east.

Sometime around A.D. 800 a new and much more complex way of life emerged in the Lake Sharpe area. True villages appeared for the first time and a larger population is apparent, allowed by an increased emphasis upon agriculture. Hunting continued as an important adjunct to the subsistence economy but the evidence, especially the relatively large size of the new towns, indicates a primary reliance upon farming.

The villages of the Middle Missouri Tradition, as archeologists have come to call the new development, were usually located on the bluffs overlooking the river. Typically the villages averaged between fifteen and twenty dwellings, with an estimated population of 200 to 300 people. A distinctive exception is the Sommers Site, opposite Chapelle Creek, where just over one hundred lodge depressions are visible. It is possible that more than 1,000 people lived here. There is a definite, planned arrangement of the lodges within many of the villages. They are aligned in rows parallel to the river and separated by narrow streets but, unlike our modern cities, the front of each house faced in a southerly direction.

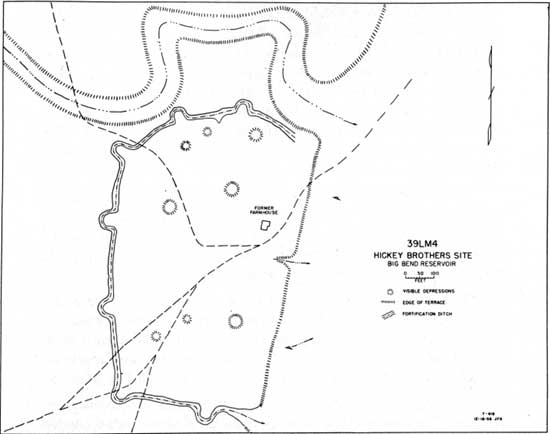

Fortifications were necessary at various times during the early village period. These defensive systems consisted of a deep, dry moat or ditch, sometimes with bastions, backed by a palisade of upright logs encircling three sides of the village. The eroded escarpment, adjacent to the river, provided sufficient natural protection so that villages were not always trenched on the side facing the river. Some village locations, such as that of the Thompson Site on the Big Bend, were apparently selected for their natural defensive characteristics. Villages built at these places occupied small, extremely steep-sided spurs or peninsulas that extended out from the main terrace edge; thus it was necessary to dig only a short trench across the base of the spur to insure adequate protection from attack.

|

| (Top to Bottom) A rim sherd decorated with horizontal rows of cord impression. A fragment of the rim and shoulder of a pottery vessel which has been marked with a cord wrapped paddle. A rim sherd with a curved profile, common during the Middle Missouri Tradition. A rim fragment typical of the Middle Missouri Tradition. |

|

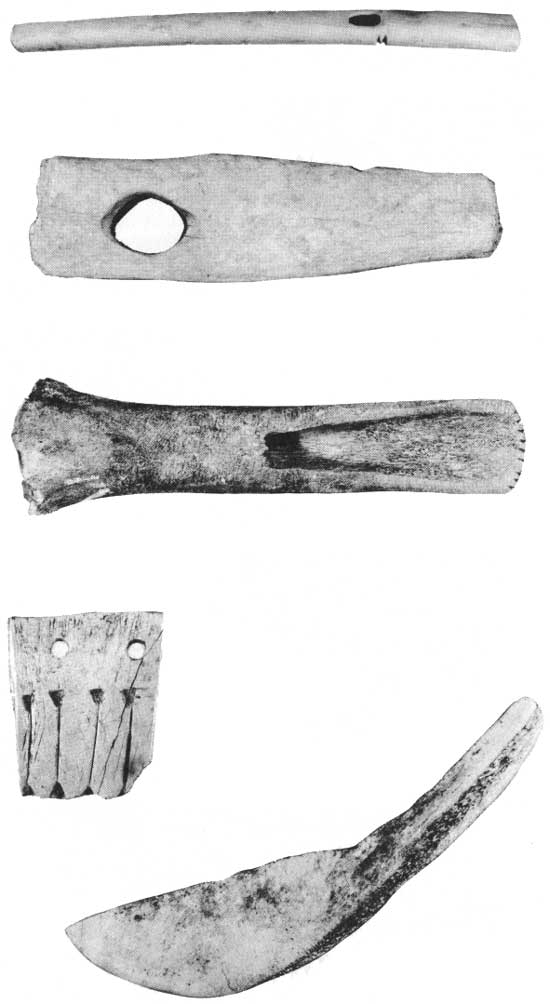

| (Top to Bottom) A whistle made from a long bone of a bird. A shaft wrench made from the spine of a bison vertebra. A serrated flesher, made from a bison leg bone and used to dress raw hides. A fragment of a bone ornament decorated with incised lines. A so-called "squash" knife made from a bison scapula. |

|

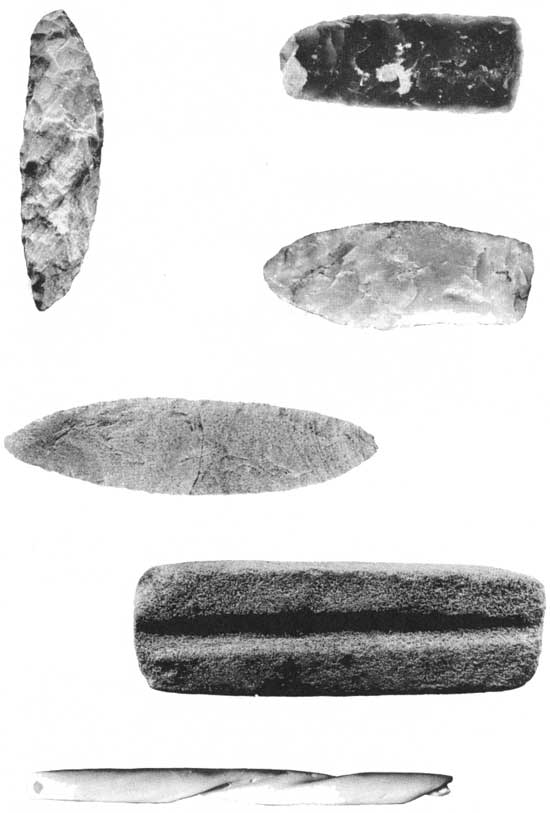

| (Top to Bottom) A chipped stone knife blade. (top, left). Long, slender scraper typical of the Middle Missouri Tradition. (top, right) A chipped stone knife blade. A long knife blade made of quartzite. A shaft smoother or abrader made of coarse sandstone. A long pendant made from the central part of a conch shell. |

|

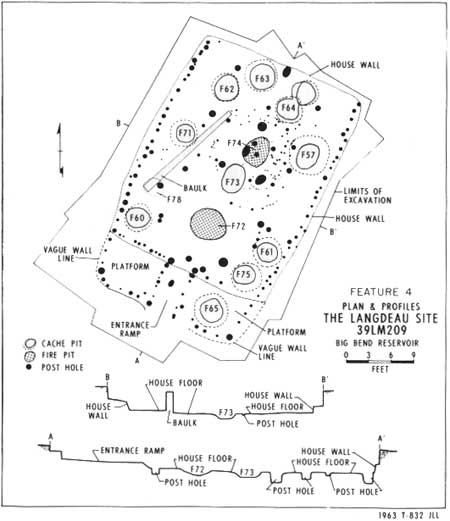

| Excavation underway in the Big Bend area of a long rectangular house typical of the Middle Missouri Tradition people. Side wall postholes may he seen at the rear of the excavation and various pit features are evident in the foreground. Photos: Courtesy of the Missouri Basin Project Smithsonian Institution. |

The early villages in the area can be easily distinguished from the later occupations by their distinctive rectangular houses. The structures average 45 feet in length and 25 feet in width, although larger houses, measuring 65 by 45 feet, are occasionally found. The floor area was excavated as much as 3 feet below the ground surface. Closely spaced, vertical wall posts were set into the floor along the two long sides of the house. The rear or northern wall was "weak," supported only by the end wall posts and the massive, central king post which also supported one end of the ridge pole. The other (front) end of the ridge pole rested on a lintel fastened to the top of the two posts which formed the interior end of a narrow passageway which protruded several feet beyond the front or southern wall. The roof was probably gabled, constructed of light poles sloping from the ridge pole down to the tops of the wall posts.

It is not known what materials were used to cover the house frame. Several burned houses have been excavated and the lack of significant amounts of burned earth suggests that these were not earth-covered lodges. Roof and siding materials were probably perishable materials such as bark, hides, grass or mats.

Although the general form of houses remained consistent throughout the early village period, variations have been found at several sites within the Lake Sharpe area. One distinctive house style has been discovered at three sites near the present community of Lower Brule. The side walls of these structures were found to extend beyond the excavated floor area for a distance equal to the length of the entrance passage (ca. 6 feet), forming a porch or bench across the front of the house. Another variation is seen in the construction of the rear wall. Although this wall is usually "weak," it was sometimes constructed with closely spaced posts in the same manner as the side walls.

The interior features of all of the houses were quite similar. A large basin-shaped hearth was excavated in the floor about six feet inside of the entrance; smaller auxiliary hearths were sometimes dug near the rear wall. Large bell-shaped cache pits for the storage of grain and other belongings were dug into the floor near the side walls. The large numbers of broken artifacts and bone scraps found in them suggest that they were also used as convenient refuse pits, probably after having become infested with mice or otherwise spoiled for the storage of valuable items.

| (omitted from the online edition) |

| Burial of a dog found on the floor of a rectangular house at a site about midway between the dam and the Big Bend itself. |

|

| Floorplan map made by an archeologist of an excavated rectangular house in the neck of the Big Bend. This type of house was in use in the region before A.D. 1000 to about A.D. 1500. Sketches: Courtesy of the Missouri Basin Project, Smithsonian Institution |

|

| Cut-away model showing construction of the rectangular house using logs, poles and brush. Photo: Courtesy of the Missouri Basin Project, Smithsonian Institution |

|

| Artists reconstruction of a part of a Middle Missouri Tradition village with rectangular houses, a palisade, and, in the right foreground, a stand for drying and storing food. |

|

| Plan of the Hickey Brothers Site in the Big Bend, a late period Middle Missouri Tradition settlement. A fortification ditch and several depressions marking house sites are shown. |

The economy was based largely upon horticulture and hunting with lesser emphasis upon gathering and fishing. Corn, beans, and perhaps other crops were raised in small plots on the river flood plain. The gardens were tilled with bison scapula hoes lashed to wooden handles. The vegetable diet was supplemented by the gathering of wild food plants. Corn and other seeds were ground into flour on large grinding stones made from native granite cobbles. Bison were the most frequently hunted animals, but deer, other small game, and birds were also pursued. The bow and arrow was probably used in hunting to judge from the large number of small, triangular projectile points of chipped stone found during excavation. Skinning and cleaning of the carcasses was accomplished by the use of chipped stone blades hafted in a bison rib handle. Thumbnail scrapers, probably hafted in the end of a rib handle, were useful in cleaning hides and in a variety of other jobs requiring scraping. Sharp bone awls were used to perforate the edges of a hide prior to sewing them together. Fish, caught with a line and bone hook, were a relatively minor dietary supplement. River mussels were also eaten and the shells sometimes used as scrapers or shaped and perforated for pendants.

Wood-working tools have been found such as grooved sandstone slabs, suitable for smoothing a shaft, and ungrooved axes of pecked stone with a polished bit. Unfortunately, with the exception of an occasional badly decayed or charred house post, no artifacts of wood have been preserved.

Two items of "costume jewelry" found at some of the early village sites were undoubtedly trade goods. Copper, probably from the Great Lakes area, was hammered into sheets and bent into cylindrical beads. Another trade item is a pendant made of the ground columella of a conch shell from the Gulf of Mexico.

Cooking vessels were of a fired clay, tempered with crushed granite. They were globular with straight, slightly curved or S-shaped rims decorated with triangular or horizontal incised lines or cord impressions. The incised motifs were most popular during the early occupations, a style that was largely replaced by cord impressing in the latter part of the period. The vessels were formed by malleating the plastic clay with a cord wrapped paddle, just as among the Woodland peoples. It was not until almost all of the rectangular house people had left the Lake Sharpe area that the grooved paddle replaced the cord wrapped tool. Bowls and miniature vessels have been found at most of the sites but they are rare.

Comparisons of the excavated artifacts and architectural features, various statistical analyses, and radiocarbon dating has made it possible for archeologists to outline the movements of these peoples. It is thought that the Middle Missouri Tradition was well established throughout the entire reservoir area by the end of the 10th century. The ultimate origin of the culture is not known but other sites with close similarities have been found further downstream in northwestern Iowa and adjacent sections of South Dakota.

It is doubtful that the movement of the villagers into the Lake Sharpe region was opposed by earlier occupants. The dearth of sites earlier than the rectangular house villages suggests that this area was largely uninhabited or held only a scattering of Woodland peoples at most. The earlier, numerically inferior groups may have been absorbed into the new towns.

Once established, the rectangular house peoples controlled the area for 400 years or more. During this time, changes in their material culture were rare and consisted, for the most part, of shifting popularity of existing traits such as the gradual change in pottery design discussed above. Despite this apparent stability, there were times of strife. The lowest level at the Pretty Head Site, occupied about A.D. 1000 and the Anderson component at the Dodd Site, dated at A.D. 1150 ± 200, were fortified. If a foreign culture was invading the area, its presence certainly was not reflected to any degree, in changes of the culture of the rectangular house people. It seems more reasonable to view the fortified settlements as participants in a "civil war" in which one rectangular house village warred upon another.

By the 14th century, Central Plains peoples from Nebraska were filtering into the Lake Sharpe area and forcing the early villagers northward. This invasion marked the end of the Middle Missouri Tradition in the vicinity of Lake Sharpe. The fortified Thompson Site, dated at A.D. 1280 ± 120 is one of the last of the early period villages in this area. A few rather atypical early period villages remained after the end of the 13th century, but they lacked the efflorescence of the villages occupied prior to the Central Plains influx.

By the late years of the 15th century, the culture of indigenous peoples of the Big Bend area had been very much modified by influences from the Central Plains. The resulting Coalescent Tradition, and outgrowth of the Middle Missouri-Central Plains mixture, is well represented in the Big Bend area. In fact, the earliest such villages, those dating from the mid-15th century, are found here and nowhere else in the Dakotas. There are not many Initial Coalescent villages and they were heavily fortified. One gains the impression that they were frontier settlements, or perhaps more correctly, islands in a hostile no-man's land.

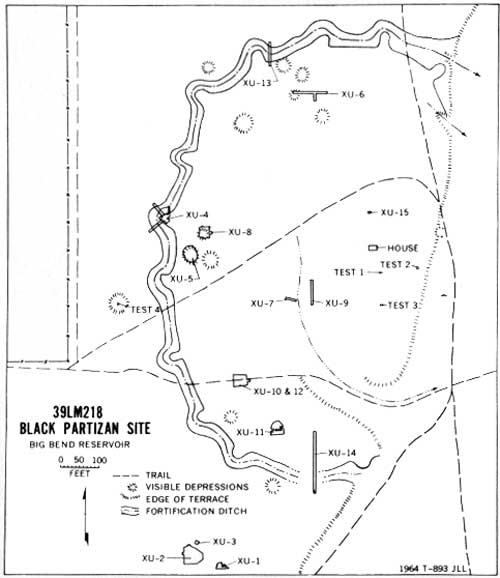

The Arzberger Site, near Pierre, the Black Partizan Site in the Lower Brule area, and the Crow Creek Site, a short distance below the Big Bend Dam, are the best examples. Each exhibits a curving fortification ditch with prominent bastions and it is probable that the defensive measures at all three sites included a high stockade.

By Coalescent Tradition times, the long-rectangular houses of the Middle Missouri Tradition had given way to rather indeterminate structures (tending toward a circular plan) that appear to have developed out of the typical square house of the Central Plains. These changes in village plan and house style were accompanied by new emphases in pottery and other artifacts. Additions and alterations were to follow in subsequent years but the pattern known from historic sources was essentially set. While the circumstances cannot be documented, it is possible that the early Coalescent peoples were the ancestors of the modern Arikara or "Ree."

The Initial Coalescent period was of rather short duration. It was succeeded in the mid-16th century by the La Roche complex, one of the last prehistoric cultures to flourish in the Lake Sharpe area. It is so named because it was first reported from a site excavated at the little settlement of La Roche, South Dakota, now under the waters of the Big Bend reservoir.

The people who built the La Roche villages were sedentary groups practicing both corn horticulture and big game hunting. Presumably, the exhaustion of the timber supply, fertile land or nearby game herds forced the people to move often, for their villages rarely show signs of lengthy occupation. The La Roche complex marked the florescence of a distinctive architectural and ceramic tradition on the Northern Plains. The prime architectural style was a circular or oval house that evolved into the historic, Plains earth lodge. Another aspect of the La Roche settlement pattern was the use of small, elaborate fortifications consisting of palisade, bastion and dry moat. However, not all of the La Roche villages were fortified and only a few had the full combination of dry moat, palisade, and bastion. Generally, the La Roche villages which were fortified are restricted to the Missouri trench area between the mouths of the Bad and Grand rivers in the Oahe Reservoir area. The La Roche villages of the Big Bend area are usually rambling, without apparent plan or defensive structures.

|

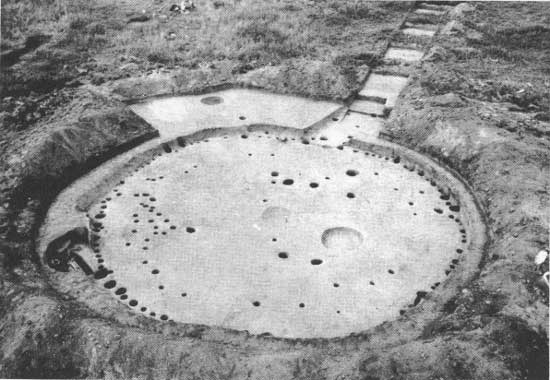

| Completed excavation of a typical circular lodge characteristic of the Coalescent Tradition peoples. Photo: Courtesy of the Missouri Basin Project, Smithsonian Institution |

|

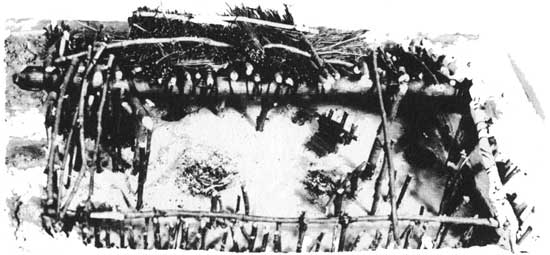

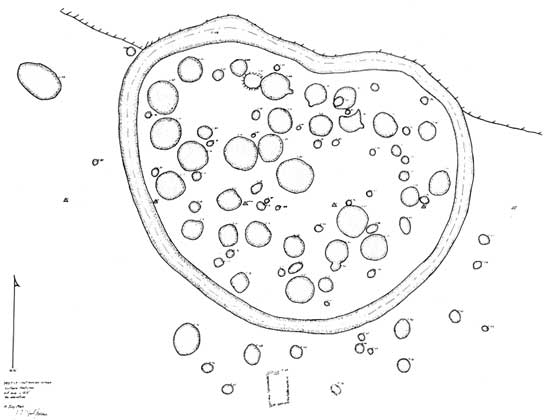

| Archeologist's map of a large, circular house at the La Roche Site in the upper Big Bend area. Reconstructed framework seen in photo #24 is based on this map. |

|

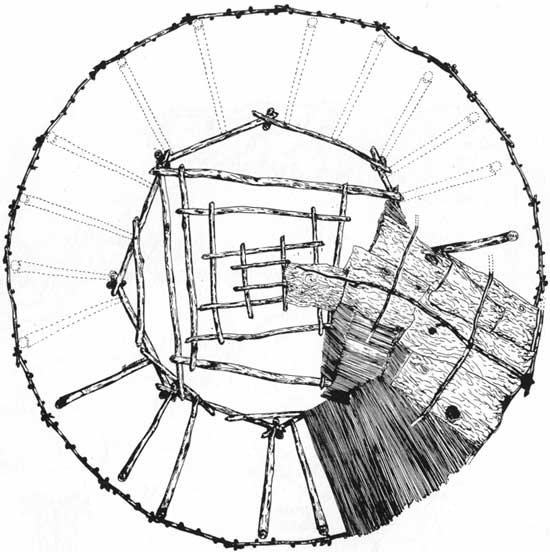

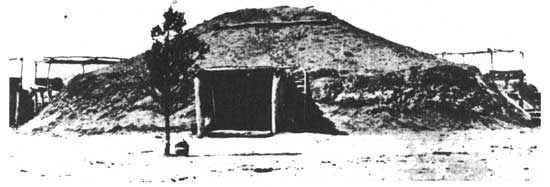

| Reconstruction of framing and roof construction of a La Roche type house, based on archeologists findings shown in photo #23. |

Like the historic Plains earth lodge, the La Roche house was built over a shallow pit or an area stripped of sod. Large posts were set into the floor and aligned vertically around the perimeter of the house. Four or more larger posts were erected nearer the center of the floor as the basic roof support. The space between the post tops was spanned with pole rafters and covered in turn with brush, grass and usually earth. The completed house resembled a large, earthen dome.

Not all of the La Roche houses were earth lodges. Some structures were so large and flimsy that they would not support an earthen mantle, and presumably were covered with only brush and bark. In fact, the many subtle variations of house styles in the earlier Initial Coalescent and in the subsequent La Roche complex have led some archeologists to believe that these structures were built during a period of architectural experimentation in the Missouri Valley.

|

| Map of features at the Black Partizan Site in the Big Bend. This site was occupied during two periods, one early and one late in the Coalescent Tradition. Sketches: Courtesy of the Missouri Basin Project, Smithsonian Institution. |

|

| Ground plan showing circular houses and enclosing fortification ditch of a typical late Coalescent village. |

|

| An historic, Arikara earth lodge photographed in 1870 at Like-a-Fishhook Village in central North Dakota. This ceremonial lodge though larger than the ordinary house, is much like the circular lodges of the Coalescent Tradition uncovered by archeologists. (Photo courtesy of the State Historical Society of North Dakota). |

Where entrances are found in the La Roche houses, they invariably face towards the Missouri River or the nearest stream course. The majority of the entrances were narrow, tunnel-like passages that projected outward from the house wall. An aberrant type has also been found that projects into the house.

Houses range from about 30 feet in diameter to about 75 feet in diameter, with 40 to 50 feet the most common dimension. The larger structures do not seem to differ functionally from the smaller ones; that is, they are not "ceremonial" houses but true, domiciliary structures to judge from the household rubbish scattered. in and around the houses.

|

| Artist's conception of horticulturalists use of a bison scapula hoe mounted on a handle. |

La Roche pottery is distinctive in its combination of decorative elements, construction, form and surface finish. The typical pot has very thin walls, is globular in shape, and has an elaborately decorated rim. The globular vessel bodies bear markings which indicate malleation with a paddle into which grooves had been carved. The construction and decoration of these vessels is remarkably consistent and show only minor differences from one area to the next. Decoration was done by incising or cutting the damp clay with a pointed bone or wooden tool prior to firing. The result was a repeated series of simple, geometric figures, usually bands of parallel lines or triangles filled with lines. Small circular impressions occasionally augmented the incised lines. The same designs were often used to ornament the upper bodies of the pots as well as the rims.

|

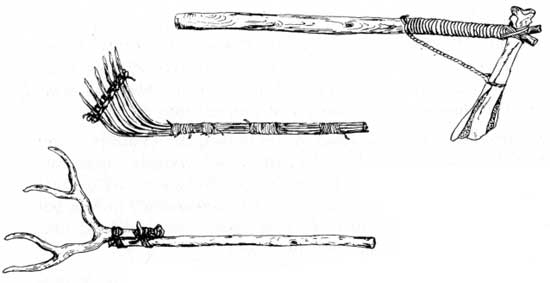

| Three implements, left to right: antler fork, willow rake and hafted bison scapula hoe. Sketches: Courtesy of the Missouri Basin Project, Smithsonian Institution |

Most of the La Roche vessels were for cooking and the carbonized remains of many a burnt dinner have been found sticking to broken sherds.

The La Roche people also made many tools of stone and bone. Local varieties of sedimentary and metamorphic rocks were carefully chipped into knives, scrapers, and arrow points for the killing and processing of game. Bison was the favored game although deer and antelope were also used. They furnished not only food but clothing, footwear, shelter, tool materials and numerous items of daily use. The shoulder bone or scapula of the bison was a useful item; hoes, knives, scrapers, cleavers and fish hooks were fashioned from it. The ribs and certain leg bones of the bison and deer were fashioned into awls and needles. Many of the bone tools were shaped by grinding with sandstone blocks or chunks of porous scoria or clinker. Mauls and grinding stones used for the preparation of meats and vegetables were made from large, water-worn cobbles.

La Roche villages were usually built on terraces overlooking the Missouri River or the mouths of its larger tributaries. As noted before, some villages were fortified; others consisted of houses scattered along the terrace in a rather loose, open settlement. Almost invariably, the site of the village was adjacent to a section of bottom land suitable for horticulture. Gardening was done by hoe and soft, fertile ground was necessary.

Besides corn, the people probably raised beans, squash and pumpkins and gathered the local wild plums and berries. In addition to big game, fish and river mussels, the La Roche people were quite fond of dog meat and the remains of many a "puppy stew" have been found in the villages. In fact, the diet of these people was almost the same as that of historic village tribes of the area, notably the Arikara.

By late prehistoric and early historic times, the La Roche ceramic tradition had given way to what archeologists call Stanley Ware, a distinctive, heavier pottery. Occupations at the Chapelle Creek and Fort George Village sites in the upper reaches of Lake Sharpe are characterized by this type of pottery. Both of these settlements were small, fortified by a simple encircling ditch and palisade, and contained circular earth lodges like those reported by early explorers and travelers. Both villages produced trade materials; and on this basis Fort George village is judged to be the most recent although it was surely abandoned before A.D. 1750. It may well have been the last substantial, and presumably Arikara, village occupied within the Big Bend country.

After about 1750, the area was left to wandering bands of Siouan (Dakota) hunters, the ancestors of the modern Dakota who still live in the region on reservations set aside for them by the Federal Government.

|

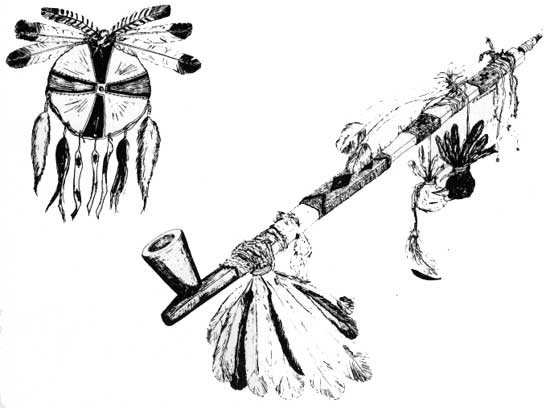

| (Top left) A hide shield like those made by the Sioux; it is decorated with feathers, fox tails, scalps and beaded strips. (Right) A pipe typical of late period Indians of the northern Plains; the bowl is carved of catlinite (pipestone), the long stem is made of wood and the pendant decor of feathers and birds heads. |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

sec3.htm

Last Updated: 08-Sep-2008