|

CRATER LAKE

Administrative History |

|

|

VOLUME II |

CHAPTER ELEVEN:

RANGER ACTIVITIES IN CRATER LAKE NATIONAL PARK: 1916-PRESENT

The ranger force at Crater Lake National Park consisted of a small staff during the early years under National Park Service administration. In 1917 Superintendent Sparrow reported that the ranger force "consists of one permanent first-class ranger and three rangers for the months of July, August, and September." The principal duties of the rangers were enforcement of park regulations, protection of its resources, prevention and control of forest fires, and operation of the park entrance stations. Two rustic log ranger cabins were constructed in 1917 at the east and west entrances of the park to complement the existing cabin at the south entrance. [1]

The Crater Lake ranger force expanded in 1918 and 1919. One permanent year-round ranger was stationed at headquarters. In addition three temporary rangers were assigned to mounted patrol during the summer months and three were employed at the checking stations at the park entrances. [2]

The ranger force and its attendant responsibilities at Crater Lake grew slowly during the 1920s. Superintendent Sparrow reported in 1920 that during the tourist season

the regular force consisted of one superintendent, one clerk and seven temporary rangers. Three rangers were stationed at the East, West and South Entrances, one at Anna Spring, one at Government Camp and two on patrol, fire protection and trails. [3]

As visitation to the park increased the number of temporary park rangers was expanded. In 1924, for instance, the ranger force was increased to nine seasonal rangers under the direction of the permanent ranger employed at park headquarters. [4]

Despite the growth of the ranger force the responsibilities placed on them led to calls for more rangers. In 1926 Superintendent Thomson reported that an "insufficient ranger force prevents adequate protection of this 249 square miles of mountainous territory." The duties of the rangers, which stretched manpower too thin, consisted of (1) enforcing park regulations; (2) protecting wildlife; (3) patroling roads and campgrounds; (4) stocking the lake with fish; (5) aiding visitors; (6) preventing and controlling forest fires; (7) participating in forest insect control; (8) travel entrance checking and information; (9) compiling travel statistics; and (10) handling the park communication system. [5]

In 1928 Superintendent Thomson again stressed the inadequacy of the park ranger force. He observed:

Park protection was inadequate due to limited ranger personnel. One ranger and eight temporary rangers hired only for the travel season can not possibly protect an area of 249 square miles, particularly as their energies are almost entirely consumed in handling well over 100,000 visitors who enter through five stations and circulate over a road system of 67 miles. Ranger personnel is so inadequate that we don't know what goes on in the Park except upon the roads. There is no patrolling [sic], no reconnoisance [sic], no protection against poaching. [6]

In response to such complaints the ranger force was expanded during the next several years. By 1929 the force consisted of ten seasonals under Chief Ranger W.C. Godfrey. That year the checking stations at the west and south entrances were consolidated into one station at Anna Spring, thus requiring only four rangers to handle traffic checking compared to six in previous years. [7]

In 1930 a Park Service report examined the ranger organization and its primary duties. Among other things the document stated:

The ranger force constitutes the protection organization of the park. The Chief Ranger is the only year long member of this force. During the park season there are ten temporary rangers employed, including the checkers and information rangers. One of these men is already assigned to patrol along the roads and policing of camp grounds, but cannot cover all the territory that is essential. One additional patrolman is needed, in order that all the roads from the west, south and east entrances, as well as the road around the Rim, may be patrolled each day and all camps visited. . . .

It is fortunate that both the Superintendent and the Chief Ranger are experienced in fire suppression work. It is desirable also that the temporary rangers be given a two or three day training course in protection work at the beginning of their appointments. The key men in the road and trail crews and construction foreman should also be included in this school so that they will be prepared to act as crew leaders for their men in case they are called into service as fire fighters. [8]

Tragedy struck the park staff on November 17, 1930, when Chief Ranger Godfrey was found dead in the park as a result of exposure to the cold. David H. Canfield, a native of Minneapolis, Minnesota, and a graduate of the University of Minnesota, was named the new chief ranger. He took up his duties at Crater Lake in May 1931, having been transferred from Mesa Verde National Park by NPS Director Albright. [9]

During the early 1930s the Depression had a major impact on the park ranger staff. In 1933, for instance, the force consisted of Chief Ranger Canfield, permanent rangers Don C. Fisher and Charles H. Simon, twelve seasonals, and two temporary fire guards. [10] (See the table below for the backgrounds of 8 of the 12 seasonal rangers.) Two years later, however, Canfield, who had become superintendent, reported on the problems occasioned by personnel cutbacks:

Due to the lack of permanent rangers--there being only one and he was unable to devote the time, this park again fell behind the vanguard during this period of emergency monies when most parks are making great strides.

Chief Ranger [J. Carlisle] Crouch was transferred to this park from Mesa Verde late in the spring; but for several months he has been the only permanent member of the ranger force. In order to approach adequate protection of the park and to provide service to visitors it is imperative that additional rangers be authorized in the near future. [11]

BACKGROUNDS OF EIGHT

SEASONAL RANGERS

1933RUSSELL P. ANDRES--Instructor in English, at Klamath Falls Junior high school, has been with the park for the past two years as a seasonal ranger. Graduate of Stanford, having his B.A. and M.A. degrees.

GEORGE P. BARRON--Ashland, is a graduate of the school of music at the University of Oregon, and has been engaged as instructor in that department for two years. He has been in the park for the last four summers, and is pianist for the community house programs.

FERDIE A. HUBBARD--Trail, a temporary ranger for many years.

BERNARD B. HUGHES--Medford, with park the past three summers.

WALTER E. NITZEL--Medford, teacher local Junior High school, and with park several seasons.

BREYNTON R. FINCH--Medford, principal local junior high school.

MILTON E. COE--Medford, principal of Jacksonville schools.

DWIGHT A. FRENCH--Klamath Falls, athletic coach and teacher of biology, Union high school there.

Medford Mail Tribune, June 8, 1933, Steel Scrapbooks, Crater Lake, No. 41, Vol. 9, Museum Collection, Crater Lake National Park.

With increasing park appropriations the ranger force was expanded in 1936. Two permanent rangers, Wilfrid T. Frost of California and George W. Fry of Pennsylvania, joined the park staff, thus filling "a long felt need." As a result of those appointments Superintendent Canfield observed that the ranger organization was "in a position to function more efficiently, particularly after the new men are entirely acclimated, accustomed and broken into their duties." The temporary force, according to Canfield, continued "to be filled by outstandingly able men." [12]

Several accidental deaths in the park during the mid-1930s led to increased emphasis by park rangers on visitor safety, protection, and rescue operations and more rigid enforcement of park regulations. The first recorded death by drowning in Crater Lake occurred on August 31, 1935. Arthur Silva, while fishing with Melvin Simon, both of Hayward, California, lost his life when their boat capsized, the result of both men standing up and turning in the boat thus throwing all the weight on one side. The drowning, which took place near Wizard Island, was witnessed by the lookout on Watchman Peak, but it took more than an hour to recover the body.

Two deaths as a result of falls over the crater rim in 1936 and 1937 focused attention on the need for visitor protection services by park rangers. In 1937 Superintendent Canfield devoted attention to this issue in his annual report:

Two deaths by falls over the crater rim were recorded during the year. July 20, 1936, Warren Bowden, 19, Portsmouth, Virginia, was killed while attempting to climb down the crater wall near the Sinnott Memorial in violation of park regulations. He had progressed several hundred feet downward when he slipped and plunged to his death. . . .

May 31, 1937, Erma Fraley, 17, Medford, Oregon, was killed in almost the same spot as the tragedy of the previous July. She was walking on snow inside the rim against the rules of better judgment and in violation of park regulations. In her spirit of daring, she suddenly slipped and rolled and plunged to within 80 feet of the lake shore. Her body was badly broken. Park rangers, accompanied by CCC enrollees, risked life and limb by climbing down a long slide over trecherous snow to reach the body. A rowboat was also lowered from the rim to enable the party to row a half-mile to the girl. The body was carried up a thousand feet of the slide and then attached to a cable and hoist to pull it up the remaining distance.

Dozens of warnings were given during the year to visitors venturing over the crater wall and several rescues were made. Venturesome visitors climbed down the wall or up from the water and became trapped so that they could not return or proceed. While there were more people at the beginning of the 1937 summer, there seemed to be less foolhardy disregard for park regulations than the year before. [13]

As a result of keeping the park officially open on a year-round basis beginning during the winter of 1935-36 there was a need for ranger personnel in the park during the winter months. After several years of covering the winter period with temporary personnel, funding permitted appointment of two permanent rangers during the winter of 1938-39. In addition the chief ranger traveled to the park from Klamath Falls on days of expected heavy travel. Nevertheless, Superintendent Leavitt reported that the winter ranger staff was "not adequate to handle checking, road patrols, trail and boundary patrols and numerous emergency calls." He further stated:

. . . On week-ends of heavy travel of skiers, it was necessary to accept the volunteer services of members of ski clubs to patrol ski trails, and to call on the assistance of ranger personnel from the Lava Beds. The entire ranger staff were able to apply on numerous occasions the Red Cross First Aid training which they received during the fall and early winter months, several serious accidents and numerous minor accidents occurring among the skiers. [14]

By the late 1930s park administrators had determined that a park ranger training school was needed at Crater Lake to promote and develop the professionalism, efficiency, and effectiveness of the force. The two men responsible for the idea of the school were Superintendent Leavitt and Chief Ranger J. Carlisle Crouch. Thus, the first such school was held at the park during July 5-20, 1938. Various instructors were brought to the park to share the expertise of their disciplines. These included: William Howland, Superintendent of the Klamath Hatchery; Conrad Wessela, Associate Forester of the Bureau of Entomology and Plant Quarantine, Division of Plant Disease Control; and J.D. Swenson, Special Agent in Charge of the Portland Office of the Bureau of Investigation. Among the subjects covered at the school were:

History of the National Park Service

History of Crater Lake National Park

Park Organization

Ranger Organization

Checking Stations

Police Protection

First Aid

Forest Fire Protection

Fire Tools

Forest Insect Protection

Forest Disease Protection

Building Fire Protection

Fish Planting

Special Protection

The success of the school led to its becoming an annual event in the park for all rangers, ranger-naturalists, and fire control aids. [15]

In conjunction with the training school Chief Ranger Crouch prepared a "Crater Lake Ranger Manual." The manual was designed to serve as a reference guide for the park rangers in carrying out their responsibilities. According to the manual, the ranger force was established to ensure that the park was administered in line with the NPS policies. In the introductory portion of the manual Crouch observed:

Some physical developments were, of course, required to carry out the . . . principle[s] of park administration. Such improvements are undertaken and accomplished with a minimum disturbance to the natural appearance of the park. Unnecessary scarring of the landscape; destruction and injury of trees and plants in the course of construction activities; establishment of promiscuous footpaths, and explanation of rules and regulations in terms of park policies are all important for the rangers to keep constantly in mind. . . .

The Park Ranger Organization is predicated upon the broad principles of the National Park Service. In the final analysis, administration of the park, enjoyment of the park by visitors, and in fact all park activities presuppose an adequate and effective plan and execution of protection measures.

The phrases "maintain in absolutely unimpaired form" and "use, observation, health and pleasure of the people" infer a multitude of diversified activities. In the preparation of a manual of operation for the ranger organization it must be acknowledged that each detail of assignments, a ready and stereotyped answer to all inquiries, and a solution for each bewildering situation cannot be included. Reliance must be made upon your own initiative, intelligence and discriminating deductions. Rangers are far more than the "eyes and ears" of the Superintendent. You must interpret correctly and analyze carefully what you see and hear.

According to the manual the Crater Lake ranger force consisted of twenty persons. These included:

1 Chief Park Ranger

2 Permanent Park Rangers

13 Seasonal Rangers

3 Fire Guards

1 Fire Lookout

The living arrangements of the rangers, as outlined in the manual, provide an interesting commentary on what it was like to reside in the park. Unmarried rangers assigned to headquarters duty or who worked from headquarters were housed in the Ranger Dormitory. Married rangers assigned to duty at headquarters were furnished "insofar as possible, tent accommodations." Married rangers assigned to outlying stations occupied the furnished quarters, while single rangers assigned to such stations were provided with tent quarters. The park furnished a bed, mattress, chest of drawers, and bath facilities for $5.00 per month. Meals were to be obtained at the government dining room "at approved rates, usually at a cost of about $1.20 a day."

The majority of the manual was devoted to a detailed explanation of the duties and responsibilities of rangers. These duties were outlined under the following categories:

Checking Station

Forest Protection

Public Contacts

Public Campgrounds

Headquarters Assignment

Traffic and Highway

Police Protection

Winter Activities

Wildlife Activities

General and Special Patrols [16]

Increasing visitation, more extensive diversified use, and year-round operation of the park created added demands on the ranger force at Crater Lake. In January 1940 Chief Ranger Crouch prepared a report on "Ranger Protection Requirements" for the park and made recommendations for increasing the efficiency of the ranger force.

The first issue to be addressed in the report was that of "protection facilities." At the time the only ranger station in the park was located at park headquarters. In addition there were three "entrance" or "checking" stations--Annie Spring (11 miles from south boundary and 7 miles from west boundary); North (8 miles from north boundary); and Lost Creek (3-1/2 miles from east boundary). Operations at these stations included fee collection, visitor registration, gun sealing, checking in and out of deer killed outside of the park, regulations with respect to dogs and cats, truck weights and sizes and their control, and information services.

To streamline and strengthen protection operations at the entrance stations Crouch recommended establishment of ranger checking stations at each of the four park boundary entrances. He stated further:

The checking kiosk itself, it is believed, should constitute a separate unit from the station. The stations should consist of quarters for personnel, storage space for equipment and supplies, a garage for a government vehicle and a small work shop. It is not within the scope of this report to offer a design for the quarters and other buildings, but the suggestion is made that the quarters consist, in addition to standard units of living room, kitchen, bath, etc., an attached dormitory room or "bull pen" sufficiently spacious to accommodate the single men who may be assigned to the station and with separate bath facilities, thus eliminating the necessity for temporary quarters.

Crouch recommended that campgrounds be established near the projected ranger stations since campgrounds "located in close proximity to a station and handled by personnel of that station are operated far more efficiently and are used far more considerately than those located at some isolated site." In addition campgrounds near the park boundaries could be used by park visitors several months longer than the existing ones at the Rim, Annie Spring, and Cold Spring which often could not be opened until mid-June or early July because of snow.

Winter access to the park, according to Crouch, added increasing year-round responsibilities to the park ranger force. Control of snow sports and the participants themselves made it necessary to hire more rangers. According to Crouch, the "size and number of snow sports areas consistent with the use must be controlled as must the ski trails, snow fields, cross country trips, and the actions of people anywhere near the rim of the lake, on the highways and elsewhere." Aid to injured persons as a result of snow sports activities also was a major component of the rangers' duties.

Crouch strongly recommended that a permanent ranger station be built at Rim Village (a temporary station had been in use at the rim) since it was "the destination of the majority of visitors to the park and the tremendous concentration of visitors in this relatively limited area calls for definite regulatory and protection activities." The recommended permanent central ranger station would "serve as a clearing house for the multiplicity of protection work required"--parking, traffic control and regulation, information and campground services, police protection, and emergency first aid.

Competent ranger personnel were necessary, according to Crouch, for exclusive service on the lake and around its shores. The majority of fatal or serious accidents in the park occurred on the lake or in the crater, including drowning, recovery of bodies of individuals who fell into the crater, rescues of marooned persons, and search for lost persons. Protection of the forest cover in the crater and on Wizard Island from fire and other destructive elements should be provided as well as enforcement of fishing and marine regulations. Thus, a patrol boat was needed to provide park rangers with the necessary means to carry out their duties on the lake.

Crouch urged that three ranger districts be established in the park as a means of making the ranger organization more effective. The three districts would include the northern and southern sections of the park and the middle portion consisting of the park headquarters, rim, and lake areas. He observed:

Operating from the central office at Park Headquarters offers certain and obvious disadvantages. Unnecessarily long trips, lost time and expenses result in the centralized operation. To send rangers from headquarters to outlying sections of the park to handle any work is obviously not as quick and therefore not as efficient as having men stationed in these sections where they would be closer to the work and equally as familiar with it or perhaps more so than the ones from headquarters. The establishment and operation of districts would lessen the present need for so much direct supervision from headquarters and would allow more time for planning and general supervision . . . .

The North and South Districts would include 112.76 square miles or 72,166.40 acres each. Each district would include two checking stations, two camp grounds, one CCC camp and one or more contractors' camps. Each district would contain approximately 35 miles of primary highway and 70 miles of administration and protection motorways. The Headquarters District, on the other hand, would contain approximately 25 square miles or 16,000 acres, 20 square miles or 12,800 acres of which represent the water surface of Crater Lake. What this district lacks in the way of extensive area, it more than makes up in the concentration of use and extensive developments. It would include the Chief Ranger's office, the main fire equipment cache and fire dispatcher's office, administration buildings, employees' quarters, utility buildings, the Rim Area, the Rim camp ground, the Lodge, Cafeteria and overnight cabins of the operator, Crater Lake itself and its crater and the park's two primary fire lookouts.

The District Rangers would be directly responsible for protection work in the respective areas with general work plans and general supervision and coordination originating at the Headquarters Station. The volume of protection work consisting of forest protection, building fire protection, traffic and highway control and patrol, wildlife protection, checking station operations and information service, camp ground management, police protection, etc. is practically evenly divided between districts.

The Crouch report analyzed the need for additional ranger personnel in the park. The ranger force should consist of the chief ranger, and an assistant chief ranger who would handle the headquarters district during the summer and supervise ranger activities throughout the park in the winter when the chief ranger was stationed at Klamath Falls. Two permanent park rangers were needed to supervise forest protection and visitor use activities in the park. The ranger in charge of forest protection would be responsible for:

preparation and revision of plans, the Fire Atlas, reports and records; training schools for fire protection; dispatching; care and accountability for fire tools and equipment; fire studies and fire reviews; forest insect and tree disease operations, including annual inspections, reports and control measures; fire hazard reduction; wood utilization and right-of-way clearing; maintenance and supply of primary and secondary fire lookouts; fire prevention and fire suppression.

The ranger responsible for visitor services would have the following duties:

checking station operations; camp ground services; police protection, including cooperation with outside police agencies; all work connected with traffic and highway use; automobile accidents, first aid, emergency rescues and other emergency services; building fire protection, inspection of buildings for hazardous conditions, training and supervision of the Fire Brigade; care and accountability for ranger equipment other than that for forest fire protection; preparation and revision of manuals and work plans, including the Ranger Manual.

The ranger organization, according to Crouch, also needed two seasonal district rangers (north and south districts) and eleven seasonal rangers. [17]

In response to the report NPS Director Arno B. Cammerer urged Superintendent Leavitt to initiate action toward the realization of Crouch's recommendations. The five areas that he particularly supported were:

1 . Checking Stations at the park boundaries

2. Establishment of three ranger districts

3. Training school for rangers

4. Additional permanent ranger personnel

5. New engine for patrol boat [18]

During the summer of 1940 Superintendent Leavitt reported on the responsibilities and accomplishments of the ranger service. One permanent park ranger position was added to the staff in December 1939. Thirteen seasonal rangers augmented the permanent force during the summer. In addition two fire guards and two fire lookouts functioned under the supervision of the chief ranger during the summer. Leavitt noted that the ranger organization was functioning "smoothly and effectively" in spite of "very serious handicaps, due largely to an inadequate number of permanent positions." Appreciation and use of the ranger organization thus justified "a continuation of the expanded service and program."

Leavitt devoted considerable attention to the added responsibilities placed on the rangers by the winter use of the park. He noted:

The winter use of the park counts considerably more than mere wintertime travel, for this is a most concentrated and specialized use. The total travel to the park during the winter months might appear more or less immaterial as compared to the travel during the summer. The use of the park by visitors in the winter and the specialized service it requires by the park staff, however, goes a long way to counteract the greater numbers of travelers during the summer who are handled with less proportionate park force and greater ease. By way of example, the ranger s relation with a summer visitor might be confined to one contact at the entrance stations and possibly at the Rim; this is not the case with the same visitor in the winter. This visitor must receive close attention from the time he enters the park until he finally departs; his car will move over icy, snow-banked highways; it will probably be parked 10 times to the one time for the summer visitor.

The winter visitor uses the highway between Park Headquarters and the Rim to ride up to the Rim so that he might ski down; the summer visitor rides up the same hill to see Crater Lake and is away and out of the park in a comparatively short time. All protection work in the winter with respect to the use by visitors is comparable to that illustrated by the car parking example. Safety, sanitation, first aid, information, guidance, instruction, etc. are required to a marked degree for every winter visitor.

Superintendent Leavitt was particularly proud of the expanding program of the annual park ranger training school. Since the first ranger training school in 1938 had proven so valuable a second school was conducted for twenty students from July 3 to August 2, 1939. The expanded program of the school included training in such subjects as police protection, forest and building fire protection, forest insects and tree diseases, fish planting, wildlife, checking station operations, and first aid. Instructors, other than members of the regular park staff, included F.P. Keen, Bureau of Entomology; W.V. Benedict, Division of Plant Disease; W.I. Howland, Klamath Fish Hatchery; and M.C. Spear, E.E. Bundy, and Willis Wood, Special Agents of the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

One of the principal duties of the ranger force continued to be forest fire control. The ranger staff handled fifteen forest fires during the year, thirteen of which occurred within the park boundaries and two outside. Lightning started eleven of the fires in the park, one was caused by a careless smoker, and one was classified as miscellaneous. Total acreage consumed by the thirteen fires in the park was less than one acre. [19]

In February 1941 Crouch updated his 1940 report on "Ranger Protection Requirements" for the park. According to Superintendent Leavitt this supplement was designed "to keep current park protection requirements to substantiate trends, which in turn give justification for changes in administration, expansion of activities, etc. , and to emphasize the rapidly changing conditions from year to year." The supplemental report stated that the unprecedented travel to Crater Lake during 1940 emphasized "the urgent need for permanent personnel to look after this all-out use of the park." Despite the spiraling visitation "the numerical strength of the protection personnel remained stationary, and very definitely below a minimum required to perform satisfactorily even the most essential services expected of this division." A temporary structure had been used in the Rim Village area as a clearing house for protection activities, but a permanent ranger station was needed. Operations during 1940 substantiated the recommendation for ranger and checking stations at the north, south, east, and west entrances to the park.

Ranger districts had been established in the northern, southern, and headquarters/rim areas of the park. A fourth district had been created in the Lost Creek area "due to the extraordinary conditions prevailing in and the attention required for the Yawkey lands in the southeast corner of the park." While the districts provided for greater efficiency in ranger services Crouch observed that the "one outstanding deficiency in the operations was a complete lack of District Rangers notwithstanding the effective work accomplished by those designated Acting District Rangers." He observed:

In the case of two districts, it was necessary to designate seasonal rangers as Acting District Rangers and all other rangers assigned to these districts were seasonal men. The work expected and actually performed by these two men were those of a District Ranger, and yet it is not in conformity with good personnel management to expect them to continue in such assignments with their present ratings. The operation of the district system the past year more than justified its establishment. A continuation of the district organization will insure an increase in the aggregate volume of protection business and a greater efficiency together with a more substantial return from the funds expended for protection. Two District Ranger positions should, therefore, be established to make this possible.

Crouch also recommended the addition of an assistant chief ranger position to the park staff:

The need for an Assistant Chief Ranger position continues apparent. Assistance in the general operation of the department--selection, training and supervision--is greatly needed in the summer season and equally so or more so in the winter season when the Chief Ranger is assigned to Klamath Falls or Medford. One member of the ranger staff has to assume responsibility for and supervision of protection activities in the park during the winter, such assignment comparing in every respect to the seasonal rangers who were designated Acting District Rangers. The work in the park during the winter must be largely planning and supervision, following general and broad programs, and places on the man greater responsibility and requires a greater scope of activities, both quantity and quality, than was contemplated in a Grade FCS 8 Ranger position. The work of this man is in every respect that contemplated in the classification of Assistant Chief Ranger and such a position should be established. [20]

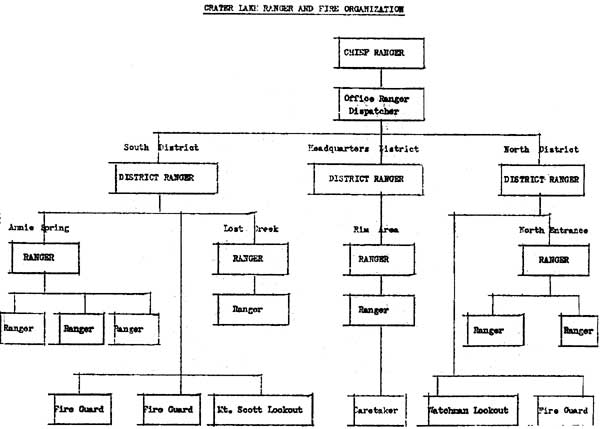

By the fall of 1942 a "Crater Lake Ranger and Fire Organization" plan had been developed. It was reported that the district ranger system was working well, both in routine and emergency situations. The fire protection efficiency of the ranger force was proven by the fact that of the 23 fires (21 lightning-caused, 1 man-caused, and 1 miscellaneous) occurring in the park during the year, only one exceeded the Class A acreage of a maximum of 1/4-acre and that one covered 0.77 acre. Fire protection during the year was enhanced by the completion of telephone lines from the rim to the north entrance checking station and from the park to a U.S. Forest Service guard station east of the park.

Temporary checking kiosks were placed in the center of the road at the east and north entrances during 1942. The kiosks proved to be "highly satisfactory, facilitating checking operations a hundredfold, and providing a safe and convenient place for ranger records and files." Leavitt desired similar kiosks at the south and west entrances as the existing Annie Spring station serving those entrances was "unsatisfactory for proper control, orientation, and direction of visitors." [21] (See the below for a copy of the "Crater Lake Ranger and Fire Organization.")

American entry into World War II had a significant impact on the ranger organization and activities at Crater Lake. In June 1942, for instance, the annual field ranger school held in the park combined the normal training in fire control, law enforcement, and other protection services with civilian defense training. The latter included training in defense against war gas and incendiary bombs and understanding of civilian defense organizations and functions. [22]

Crater Lake was operated on a bare maintenance level during the war as a result of reduced park appropriations and personnel . Park rangers performed a variety of untraditional tasks during the war emergency in addition to their principal responsibilities for fire protection and safeguarding of government property. In June 1943 Superintendent Leavitt reported that the chief ranger and the park naturalist undertook the major responsibility for trail repair and other maintenance work and furnished crews to assist the park carpenter, plumber, road foreman, and engineer in their duties. Leavitt noted:

. . . Without this fine spirit of loyalty among the more experienced and trained personnel, we would have accomplished very little, as the only unskilled labor we were able to procure was a few young boys just old enough to qualify under the age regulations, and a few old men.

The administrative heads of Crater Lake feel moved to praise and compliment the entire force for their unselfishness, loyalty to the Service and fine spirit as evidenced by the willingness to do anything and everything they could, and for the energy displayed in every department. The accomplishments with a minimum force were remarkable. To see a group of rangers and ranger naturalists in work clothes toiling at cleaning up large rock slides and fallen trees from the roads and trails, the rangers moving and rebuilding a boat house, and doing many other tasks calling for hard physical labor as well as skill and ingenuity, is convincing proof of the superiority of the Crater Lake staff, for every one did all he could to carry on with a willing and cheerful spirit. [23]

Fire protection was the primary concern of the park ranger force during the war. The park master plan in February 1944 indicated that fire protection personnel consisted of the chief ranger, one park ranger, two seasonal fire guards, two seasonal fire lookouts, and seven seasonal rangers. As outlined in the master plan the duties of the protection organization related almost entirely to fire prevention and control. The responsibilities were:

Recruiting, training and directing of fire protection personnel; supply and maintenance of lookouts; requisition, maintenance and use of fire tools and equipment; prevention education; fire hazard reduction; fire detection, suppression and fire studies. [24]

The park, which had been closed during the winter months throughout the war years, resumed regular year-round operations on June 15, 1946. Chief Ranger Crouch and a small staff of temporary rangers were on duty in the park several days before the official opening By June 30, however, a staff of twelve temporary rangers and six fire control aides were working. Checking incoming park visitors was resumed with the opening of the park, and temporary checking stands were built at the south and west entrances. Checking at the park boundaries was found "to be highly advantageous," and the traffic jams, common when cars from both entrances were checked at Annie Spring, were eliminated. Regional Forester Burnett Sanford arrived at Crater Lake on June 30 and took part in the three-day ranger and fire training school for park rangers and fire control aides that had been resumed by Crouch.

The duties of the park ranger force reverted to prewar standards during the late 1940s. Fire control, law enforcement, and visitor protection were the principal responsibilities of the rangers during the summer travel seasons. Heavy winter use of the park by skiers and other snow sports enthusiasts necessitated various

precautionary measures by the rangers, including installation of the safety rope at the crater edge on the Rim, posting of signs, first aid, checking, traffic control, and assistance to Park visitors in pulling stuck cars back on the road, from drainage ditches on the upper side of the roads, or from below the road when they slipped or skidded off the lower side of the road grade. Rangers contributed time and effort in repairing the telephone and electric systems. [25]

The role and functions of the Crater Lake ranger force continued to be refined and expanded during the 1950s. In June 1955 an organization and function statement was prepared for the park. According to the document Chief Ranger Carlock E. Johnson was in charge of the protection division and had the following responsibilities:

Supervises activities related to protection of life and property, and preservation of park values. Plans, coordinates and supervises projects for control of tree disease and injurious forest insects. Performs all law enforcement and traffic control duties. Collects automobile entrance fees. Disseminates complete and accurate information relating to public use of the area. Cooperates in studies of wildlife and aquatic populations and accompanying problems of habitat use or population stabilization; supervises fish planting. Maintains cooperative weather stations, snow survey courses, and civil defense activities. Organizes and directs forest and building fire presuppression and suppression activities. [26]

There were few changes in the organizational structure or responsibilities of the park ranger force during the next decade. A park organization chart prepared in October 1962 indicated that the ranger force consisted of five permanent positions. There were a chief and an assistant chief ranger and supervisory park rangers in charge of the Annie Spring (south) and Red Cone (north) districts. One park ranger was assigned to the Annie Spring District. The remainder of the ranger force consisted of seasonals as required." [27]

The duties of the supervisory park rangers were outlined in a position description certified by Assistant Regional Director Keith Neilson on March 20, 1963. The list included nine areas of responsibility:

1 . Protection of life, property, and the preservation of park values

2. Control of forest insect and tree diseases

3. Law enforcement and traffic control

4. Direction of checking station procedures and operations

5. Dissemination of information relating to public use of the area

6. In-service training

7. Wildlife and aquatic populations and accompanying problems

8. Search and rescue

9. Maintenance [28]

During the 1960s Crater Lake park management promoted development and improvement of methods and standards for visitor protection and resource management. This goal was to be achieved by emphasizing effective manpower utilization of the ranger force. In 1965, for instance, such an emphasis took the form of five objectives.

a. Continue the present programming of road patrols with the present low accident frequency rate.

b. Increase trail patrol, maintenance and improvement.

c. Continue the desire to furnish the very best of equipment and outside training for all permanent protection staff.

d. Continue the practice of on-the-job training for all seasonal employees.

e. Improve visitor contact by increasing dissemination of basic information at entrance stations by the use of visual aids and handouts. [29]

By the mid-1970s the park ranger force had been placed under the Division of Interpretation and Resource Management. Answering to the chief of the division were two supervisory park rangers and one park aid. During the summers the park employed about twenty seasonal rangers and nine seasonal fire control aides. The duties of the rangers, which had changed little over the years, included:

. . . the responsibility of the protective personnel to protect the park and its features from damage, misuse, or destruction, and to provide for the safety and health of the park visitors and employees. This responsibility includes traffic control, forest and building fire control, tree disease and insect control, public health and sanitation, accident investigation, law enforcement, first-aid, search and rescue, protection of wildlife, collection of motor vehicle fees, distribution of information to park visitors, and other related areas. [30]

As a result of park reorganization the ranger force had been placed under the Resource Management and Visitor Protection Division by the early 1980s. An updated function statement prepared for the division in September 1986 indicated that the work of the division was supervised by four specialists under the direction of the chief. The specialists were in the fields of resource management, natural resources, law enforcement, and fire management. Supervision of various ranger activities fell under each of the specialists. [31]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

crla/adhi/chap11.htm

Last Updated: 13-Aug-2010