|

CRATER LAKE

Administrative History |

|

|

VOLUME II |

CHAPTER FIFTEEN:

VISITATION AND CONCESSIONS OPERATIONS IN CRATER LAKE NATIONAL PARK: 1916-PRESENT

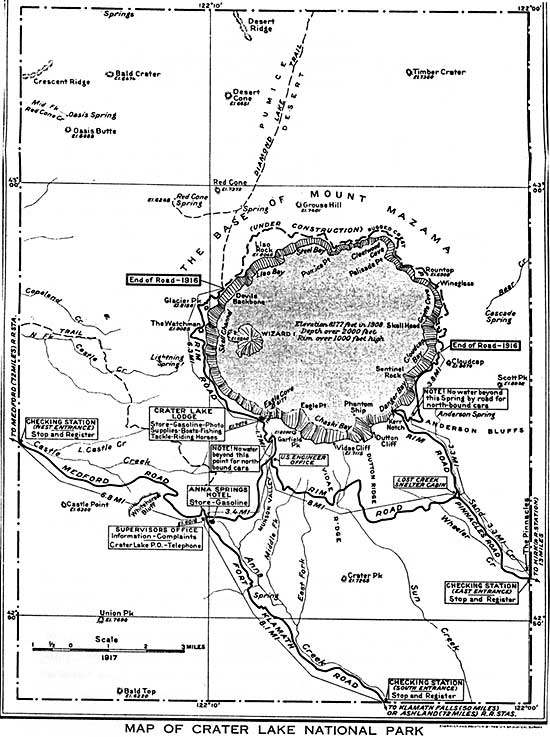

As one of the "jewels" of the embryonic National Park System, Crater Lake National Park became the focus of Park Service publicity efforts to promote visitation. In 1917 the bureau issued an automobile guide map (a copy of which may be seen below) for the park. The map showed automobile highways leading to the park as well as the park road system, visitor accommodations, trails, and points of interest.

At the behest of NPS Director Mather, the Crater Lake publicity effort was supported by the Southern Pacific Railroad and the National Parks Highway Association. The railroad promoted travel to Yosemite, Sequoia, Lassen Volcanic, and Crater Lake national parks with various excursion fare offers. As a result of negotiations between Mather and the railroad, tickets between Portland and California points during 1917 entitled purchasers to stop over at Medford for a trip to Crater Lake. If a traveler entered the park via one gateway and left by another, his ticket was honored for continuation to his destination. Hence it was possible to go to the park from Klamath Falls and exit out the western gateway to Medford in connection with a trip to Portland. On the other hand, a party bound for California was permitted to stop at Medford, go through the park, and connect again with the Southern Pacific Railroad lines at Klamath Falls.

The National Parks Highway Association, with headquarters in Spokane, assumed leadership in designating a park-to-park highway connecting the major national parks in the West. During the spring of 1917, the association mapped and sign-posted a route from its terminus of the previous year in Mount Rainier National Park to Crater Lake, thus connecting Yellowstone, Glacier, Mount Rainier, and Crater Lake national parks by what was known as the National Parks Highway.

In addition to these efforts, the National Park Service continued the practice of the Department of the Interior in publishing annual general information circulars for the parks. The 1917 circular for Crater Lake not only described the park's scenery and resources in glowing terms but also its visitor accommodations, transportation facilities, and means of reaching the park. The circular described the lake as an "unforgettable spectacle":

Crater Lake is one of the most beautiful spots in America. The gray lava rim is remarkably sculptured. The water is wonderfully blue, a lovely turquoise along the edges, and in the deep parts, seen from above, extremely dark. The contrast on a sunny day between the unreal, fairylike rim across the lake and the fantastic sculptures at one's feet, and in the lake between, the myriad gradations from faintest turquoise to deepest Prussian blue, dwells long in the memory.

Unforgettable also are the twisted and contorted lava formations of the inner rim. A boat ride along the edge of the lake reveals these in a thousand changes. At one point near shore a mass of curiously carved lava is called the Phantom Ship because, seen at a distance, it suggests a ship under full sail. The illusion at dusk or by moonlight is striking. In certain slants of light the Phantom Ship suddenly disappears--a phantom, indeed.

Another experience full of interest is a visit to Wizard Island. One can climb its sides and descend into its little crater.

The somewhat mysterious beauty of this most remarkable lake is by no means the only charm of the Crater Lake National Park. The surrounding cliffs present some of the most striking pictures of the entire western country. These can best be studied from a boat on the lake, but the walk around the rim of the lake is one of the most wonderful experiences possible.

The circular provided considerable information on the services and accommodations provided by the Crater Lake Company, which had agreed to a revised five-year concession contract with the Department of the Interior effective January 1, 1917. The company operated daily automobile service between Medford (83 miles from the park) and Klamath Falls (62 miles from the park) and Crater Lake. Automobiles left the Hotels Medford and Nash in Medford each morning, stopped for lunch at Prospect, and reached the lake in the evening. Returning automobiles left Crater Lake each morning, reaching Medford in time to connect with outgoing evening trains. Automobiles left the White Pelican Hotel in Klamath Falls each morning and arrived at the lake at noon. Returning automobiles left the lake after lunch and reached the White Pelican Hotel in time for supper. The rates for these automobile services were:

| Medford to Crater Lake and return One way (either direction) | $15.00 |

| Klamath Falls to Crater Lake and return One way (either direction) | 8.50 |

| Medford to Crater Lake, thence to Klamath Falls, or vice versa | 15.00 |

The circular described the hotel and camps operated by the Crater Lake Company in the park. These accommodations, along with the rates charged for such services, were:

Crater Lake Lodge, on the rim of the lake, is of stone and frame construction and contains 64 sleeping rooms, with ample bathing facilities as well as fire protection. Tents are provided at the lodge as sleeping quarters for those who prefer them, meals being taken at the lodge.

At Anna Spring Camp, 5 miles below the rim of Crater Lake, the company maintains a camp for the accommodation of guests, a general store (with branch at Crater Lake Lodge) for the sale of provisions and campers' supplies, and a livery barn.

The authorized rates are as follows:

Rates at Crater Lake Lodge | |

| Board and lodging (lodging in tents), one person: | |

| Per day | $ 3.25 |

| Per week | 17.50 |

| Board and lodging, two or more persons in one tent: | |

| Per day | each 3.00 |

| Per week | each 15.00 |

| Lodging in tents: | |

| One person, per night | 1.00 |

| Two or more persons in one tent, per night | each .75 |

| Board and lodging (lodging in hotel), one person: | |

| Per day | 3.75 |

| Per week | 20.00 |

| Board and lodging, two or more persons in one room: | |

| Per day | each 3.50 |

| Per week | each 17.50 |

| Lodging in hotel: | |

| One person, per night | 1.50 |

| Two or more persons in one room, per night | each 1.25 |

| In hotel rooms, with hot and cold water: | |

| Board and lodging, one person | |

| Per day | 4.25 |

| Per week | 22.50 |

| Board and lodging, two or more persons in room | |

| Per day | each 4.00 |

| Per week | each 20.00 |

| Lodging | |

| One person, per night | 2.00 |

| Two or more persons in one room, per night | each 1.75 |

| Baths (extra) | ,50 |

| Fires in rooms (extra) | .25 |

| Single meals | 1.00 |

| |

| Board and lodging, each person: | |

| Per day | 2.50 |

| Per week | 15.00 |

| Meals: | |

| Breakfast or lunch | .50 |

| Dinner | .75 |

| Children under 10 years, half rates at lodge or camp | |

The Crater Lake Company operated a general store at Anna Spring Camp and a branch store at Crater Lake Lodge. The stores sold provisions, tourists' supplies, gasoline, motor oil, hay and grain, fishing gear, drugs, Kodak film supplies, and bakers' goods.

While visitors were permitted to provide their own transportation and to camp in the park, subject to regulations, the Crater Lake Company operated in-park concession automobile, saddle horse, and stage transportation services. Fares and rates for these services were:

| AUTOMOBILE | |

| Fare between Anna Spring Camp and Crater Lake Lodge: | |

| One way | $0.50 |

| Round trip | 1.00 |

| Transportation, per mile, within the park | .10 |

| Special trips will be made when parties of four or more are made up, as follows: | |

| To Anna Creek Canyon, including Dewie Canyon and Garden of the Gods, 24-mile trip, for each person | 2.00 |

| To Cloud Cap, including Kerr Notch, Sentinel Rock, and Red Cloud Cliff and Pinnacles, 40-mile trip, for each person | 3.00 |

| The Sunset Drive, from Crater Lake Lodge to summit of road at Watchman, at sunset, 10-mile trip, for each person | 1.00 |

| HORSE | |

| Saddle horses, pack animals, and burros (when furnished): | |

| Per hour | 0.50 |

| Per day | 3.00 |

| Service of guide, with horse: | |

| Per hour | 1.00 |

| Per day | 3.00 |

| ON CRATER LAKE | |

| Launch trip: | |

| Wizard Island and return, per person | .50 |

| Around Wizard Island and Phantom Ship and return (about 15 miles), per person | 2.00 |

| Around the lake | 2.50 |

| Rowboats: | |

| Per hour | .50 |

| Per day | 2.50 |

| With boat puller, per hour | 1.00 |

| With detachable motor | |

| Per hour | 1.00 |

| Per day | 5.00 |

The circular also contained a section on the principal points of interest (a copy of which may be seen on the following page) in the park and nearby areas. Arrangements for trips to these points in the park could be made at the Crater Lake Lodge. For trips to Mount Thielson, Diamond Lake, and other remote points camp equipage, pack horses, and a guide could be secured at the lodge. [1]

PRINCIPAL POINTS OF INTEREST.

Distances from Crater Lake Lodge by road or trail to principal points.

| Name. | Distance and general direction. |

Elevation above sea level. |

Best means of reaching. |

Remarks. |

|

Llao Rock Diamond Lake Devil's Backbone Glacier Peak The Watchman Garfield Peak Dyar Rock Vidae Cliff Sun Notch Dutton Cliff Sentinel Rock Cloud Cap Scott's Peak The Pinnacles Garden of the Gods and Dewey Falls Anna Creek Canyon Union Peak Wizard Island Phantom Ship |

8 north 18 north 6.5 north 6 north 5 north 1 east 2 east 3 east 7 east 9.5 east 18 east 20 east 22 east 15.5 southeast 5 10 to 13.5 south 10.5 southwest 3.5 north 3 east |

8,046 ..... ..... 8,156 8,025 8,060 7,880 8,135 7,115 8,150 ..... ..... 8,938 ..... ..... ..... 7,698 6,940 ..... |

Auto to Glacier Peak, then on foot. Horseback Auto Auto and foot do Foot or horseback do do Auto and on foot do Auto do Auto and on foot Auto do do Auto and foot Foot and boat do |

Fine view. Point from which Llao's body was thrown into lake. All-day trip. Pretty lake. Near view of Mount Theilson. Fine view of formation and coloring of Glacier Peak. Highest Point on rim of lake; fine view. Fine view; easy climb Hard climb on foot. If taken on horse- back distance is 6 miles. Fine view. Monster bowlder, 100 feet high. Hard climb on foot. If taken on horseback distance is 6 miles. Fine view. Easy trip by horse; distance 7 miles. Fine view of Phantom Ship. View of Vidae Falls. Walk 1 mile. Easy trail. Fine view; 7.5 miles by auto, 2 miles on foot. Most comprehensive view from rim of lake. End of auto road. Fine drive. Good scenery. 2 miles by trail from end of road at Cloud Cap. Highest point in the park. Grotesque formations. Nice trip. Waterfalls, meadows, pinnacles, and pretty canyons. Beautiful canyon, 300 to 400 feet deep. 4 miles by trail from road. Hard peak to climb. Good view. Extinct volcano crater in summit. Trail to top. Grotesque rock, pinnacled island. |

Despite these publicity efforts, visitation to Crater Lake declined in 1917, primarily because heavy snowfall in late spring delayed regular tourist travel by several months. After considerable "shoveling of snow" by Crater Lake Company employees, automobiles arrived at park headquarters on July 7 and at Crater Lake Lodge on July 18. The roads, however, were not in condition for regular travel until August 1. The number of visitors and automobiles that entered the park in 1916 and 1917 were:

| Visitors |

Automobiles | |||

| 1916 | 1917 |

1916 | 1917 | |

| East Entrance | 859 | 1,174 | 193 | 293 |

| West Entrance | 9,571 | 5,368 | 1,293 | 1,234 |

| South Entrance | 1,835 | 5,103 | 1,163 | 1,229 |

12,265 | 11,645 |

2,649 | 2,756 | |

A total of 1,766 automobile and 15 motorcycle licenses were issued during 1917, and $4,433 in receipts were collected from vehicles entering the park. [2]

Among the visitors to the park during 1917 was a large group of members of the Knights of Pythias Order. On August 14 the group held initiation ceremonies in the crater of Wizard Island--a practice that had been commenced several years earlier. [3]

Weather continued to play a major role in determining the extent of park visitation. The light snowfall of only ten feet during the winter of 1917-18, combined with warm weather early in the spring, made it possible for automobiles to reach the lake by June 18, one month earlier than the preceding year. As a result visitation to Crater Lake increased to 13,231 in 1918. The numbers of visitors entering the park were:

| Pinnacles Road | 1,193 |

| Fort Klamath Road | 5,625 |

| Medford Road | 6,413 |

13,231 |

The statistics relating to the means of transportation of the visitors were:

| Crater Lake Stage | 516 |

| Automobiles | 11,471 |

| Wagons | 1,022 |

| Motocycles | 10 |

| Mounted on Horse | 185 |

| On Foot | 27 |

13,231 |

The number of motor vehicles entering the park were:

| Pinnacles Road | 267 | |

| Fort Klamath Road | 1,305 | |

| Medford Road | 1,533 | |

3,105 |

[4] |

In 1919 visitation increased by more than 25 percent to 16,645, while the number of motor vehicles entering the park rose by some 50 percent to 4,637. Several delegations of visitors toured the park in 1919, thus showing the increasing popularity of the park Among the visiting contingents were 66 members of the Massachusetts Forestry Association on July 28-30 and 17 members of the Travel Club of America on August 16-18. The most illustrious visit, however, occurred on August 11 when nearly 400 members of the National Editorial Association visited the park. Since the lodge could not accommodate all of these guests, the Ashland and Medford chambers of commerce furnished blankets and camping supplies and the park contributed tents for the convenience of the group. [5]

The 1919 general information circular advertised several new attractions in the park that were designed to enhance the visitor's experience. The public camp grounds on the rim west of the lodge had been enhanced, one of the principal improvements being the installation of a large tank and pumping equipment to furnish an ample water supply not only for drinking and cooking purposes but also for showers. Sightseeing opportunities had been improved by a

splendid new trail from Crater Lake Lodge to the shore of the lake. . . [It] has given pleasure and refreshment to thousands, and, as was expected, elderly people and visitors wholly unaccustomed to climbing availed themselves of the opportunity to make the delightful trip from the lodge to the edge of the lake, thence in motor boats around the lake to Wizard Island and the Phantom Ship, and to other points of interest. The new trails to Garfield Peak and the Watchman were also exceedingly popular during the past season. A trail to the summit of Union Peak was constructed last year.

Five small launches, ten steel rowboats, and a 36-foot boat had been ordered by the Crater Lake Company to replace seven rowboats and a small launch that had been damaged in a storm the previous September. In addition to these boats that were available for rent by the hour or day, an expanded schedule of launch trips on the lake was provided:

| Launch trips: | |||

| Wizard Island and return, on regular schedule, launches leaving lake shore at 9 a.m., 11 a.m., 2 p.m., and 5 p.m., per person | .50 | ||

| Wizard Island and return, special trip, per person | 1.00 | ||

| Around Wizard Island and Phantom Ship and return (about 15 miles), per person | 2.00 | ||

| Around the lake | 2.50 | [6] | |

Visitation to Crater Lake increased by more than 20 percent in 1920 to 20,135. NPS Director Mather reported on the reasons behind this increase:

Travel to Crater Lake Park has each year shown a healthy increase over the previous year, and again this season we have a most gratifying increase over last year, despite the gasoline shortage and other circumstances that threatened several times to discourage or curtail long tours by automobile. It was noted also that motorists were more inclined to stop over in the park, and camp with their own outfits longer, than it has heretofore been their custom to do. There certainly exists here a splendid opportunity for the development of interest in camping and fishing, but to get the very best results in encouraging this use of the park the Diamond Lake area should be added. With a road from Crater Lake to Diamond Lake the park would become at once one of the best recreation areas of the Pacific coast and would be patronized by motorists from Canada to Mexico.

Weather conditions again played a significant factor in the increased visitation. In this regard Superintendent Sparrow observed:

After strenuous efforts, snow plowing and shoveling, the road to Anna Spring via the south entrance was opened for cars on June 13, and from the west entrance on the 17th. The road from Anna Spring to the lodge was passable for automobiles June 26, and the Rim Road around the lake on July 26. This is the earliest opening of roads within the park of which we have any record. [7]

Statement showing automobile travel, by States and entrances, season of 1920.

| States. | East entrance. | South entrance. | West entrance. | Total. | ||||

| Cars. | People. | Cars. | People. | Cars. | People. | Cars. | People. | |

| Alabama | .... | .... | 1 | 4 | .... | .... | 1 | 4 |

| Arkansas | 1 | 4 | .... | .... | 2 | 6 | 3 | 10 |

| Arizona | 1 | 3 | 6 | 23 | 6 | 19 | 13 | 45 |

| California | 128 | 410 | 556 | 1,800 | 567 | 1,814 | 1,251 | 4,024 |

| Colorado | 5 | 17 | 6 | 23 | 9 | 29 | 20 | 69 |

| Connecticut | .... | .... | .... | .... | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Florida | .... | .... | 1 | 4 | .... | .... | 1 | 4 |

| Illinois | 2 | 11 | 1 | 4 | 7 | 36 | 10 | 51 |

| Indiana | 1 | 4 | 3 | 10 | 4 | 18 | 8 | 32 |

| Iowa | 3 | 10 | 5 | 14 | 2 | 16 | 10 | 20 |

| Idaho | 15 | 46 | 9 | 35 | 9 | 34 | 33 | 115 |

| Kansas | 3 | 10 | .... | .... | 2 | 5 | 5 | 15 |

| Kentucky | .... | .... | .... | .... | 3 | 8 | 3 | 8 |

| Louisiana | .... | .... | .... | .... | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Maryland | .... | .... | .... | .... | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| Massachusetts | .... | .... | .... | .... | 3 | 19 | 3 | 19 |

| Montana | 2 | 7 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 8 | 4 | 19 |

| Michigan | .... | .... | .... | .... | 3 | 14 | 3 | 14 |

| Minnesota | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 28 | 9 | 33 |

| Missouri | 8 | 16 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 18 | 15 | 36 |

| New York | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 45 | 8 | 51 |

| New Mexico | 1 | 3 | .... | .... | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 |

| New Jersey | .... | .... | .... | .... | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Nebraska | 4 | 18 | .... | .... | 6 | 26 | 10 | 44 |

| Nevada | 4 | 17 | 13 | 39 | 9 | 29 | 26 | 85 |

| North Carolina | .... | .... | .... | .... | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| North Dakota | .... | .... | .... | .... | 1 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| Oklahoma | .... | .... | 1 | 5 | 2 | 11 | 3 | 16 |

| Ohio | 4 | 11 | 2 | 4 | 10 | 34 | 16 | 49 |

| Oregon | 320 | 1,163 | 1,177 | 4,340 | 1,899 | 6,675 | 3,396 | 12,178 |

| Pennsylvania | .... | .... | .... | .... | 5 | 32 | 5 | 32 |

| South Dakota | .... | .... | .... | .... | 2 | 7 | 2 | 7 |

| Texas | 2 | 6 | .... | .... | 6 | 18 | 8 | 24 |

| Tennessee | .... | .... | .... | .... | 1 | 5 | 1 | 5 |

| Utah | 2 | 4 | 6 | 20 | 4 | 16 | 12 | 40 |

| Virginia | 1 | 3 | .... | .... | 2 | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| Washington | 31 | 97 | 46 | 172 | 70 | 204 | 147 | 473 |

| Wisconsin | 1 | 3 | .... | .... | 1 | 8 | 2 | 11 |

| Wyoming | .... | .... | 6 | 16 | 5 | 12 | 11 | 28 |

| District of Columbia | 1 | 4 | .... | .... | .... | .... | 1 | 4 |

| Hawaiian Islands | .... | .... | .... | .... | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 |

| Total | 542 | 1,809 | 1,845 | 6,528 | 2,667 | 9,220 | 5,054 | 17,617 |

| Automobile travel unclassified by States | .... | .... | .... | .... | .... | .... | 104 | 274 |

| Total all motorists, classified and unclassified | .... | .... | .... | .... | .... | .... | 5,158 | 17,891 |

| Total visitors, other means of transportation | .... | .... | .... | .... | .... | .... | .... | 966 |

| Total visitors hauled by Crater Lake Stage | .... | .... | .... | .... | .... | .... | .... | 1,278 |

| Grand total visitors, motorists and all other | .... | .... | .... | .... | .... | .... | 5,158 | 20,135 |

Annual Report of the Director of the National Park Service, 1920, pp. 279-80. The year 1920 was the first in which a statistical breakdown of automobile travel by states and entrances was compiled.

A visit to the park during July 17-19, 1920, by members of the House Appropriations Committee, accompanied by NPS Director Mather and E.O. McCormick, vice president of the Southern Pacific Railroad, brought to a head a smoldering dispute between the Park Service and the Crater Lake Company. Although reservations for the visitors were booked in advance, the lodge was not prepared to adequately care for them. This led to considerable criticism, particularly from Mather who reprimanded Crater Lake President Parkhurst and threatened to cancel his concession contract. One of the causes of the dispute was attributed to the fact that the lodge "was not opened in time to get things in working order or the crew organized before tourists began to arrive in larger numbers than had been anticipated." The incident had a negative impact on park visitation, according to Superintendent Sparrow, because "in some manner the impression got out, about July 15, that this park was closed, and many intending visitors passed us by." Sparrow took the opportunity to elaborate on some longstanding problems park management had been having with the concessioner:

During the early part of the season the service at the lodge came in for considerable criticism, most of which was justified. This was due, in part, to lack of preparation before the season opened, and inefficient organization, and lack of sufficient supplies. The lighting system was inadequate and the water system failed.

After much fault finding and criticism passed along orally and through newspapers, conditions were very much improved and for the remainder of the season but few complaints were received. A Delco lighting plant was installed which gives satisfactory service. A new pumping plant was installed, which was guaranteed to do the work, but failed entirely, and another unit is now in transit and will be installed at an early date. During this time water was furnished the lodge from the Government plant, which proved adequate for all occasions, but sometimes required a night shift to keep up the supply. Too much of the lodge is used to house employees, and it is my opinion that tents or separate buildings should be provided for the help, and if this were done the lodge, with some tents, should be sufficient to care for guests for another season or two. . . . Regardless of what the plans are for the future, there must be some temporary arrangement made to take care of tourists during the 1921 season.

The public operator has many good boats and launches on Crater Lake, but as yet there is absolutely nothing in the nature of a dock or boat landing. It is recommended that a loose-rock and concrete pier or boat landing be constructed for the convenience of tourists and protection of boats, which are always grounded on rocks when taking on or discharging passengers. . . .

Director Mather was so incensed by the problems with the lodge that he devoted considerable attention to the matter in his annual report for 1920. He described his personal dissatisfaction with the services being offered by the Crater Lake Company:

Although this is the first year I have recorded the fact in print, the management of the Crater Lake Lodge and Anna Springs Camp has never been satisfactory to me. When I first visited the park in 1915 I found an attractively planned but unfinished hotel, especially far from complete within the structure, insufficient furnishings, a scanty larder, and very ordinary dining-room service. I observed that the plant was not being operated at a profit, and upon inquiry found that the owner had invested all of his available funds in the enterprise and was unable to secure more financial assistance.

I endeavored to help him by offering suggestions regarding inexpensive improvements that would better service and make visitors to the hotel more comfortable, while further efforts were made to secure financial aid to complete the building. I secured the services of an experienced hotel operator, who visited the park and suggested perfectly feasible yet inexpensive betterments in kitchen and dining-room service. There were always promises of action on the suggestions and bits of advice, but no improvements worthy of the name were made. Year after year I visited the park, found the usual indifferent service and unfinished accommodations. I pleaded for improvement, got more promises, but never any fulfillment of agreements or understandings.

Last year I visited the park with the National Editorial Association, and although the number of members of this party was well known months before, as well as the time they would spend at Crater Lake, the management was entirely unable to care for the party in a satisfactory manner. Again I remonstrated with the owner and got more promises, only to find absolutely no compliance a year later when, last July, I visited the park with the Appropriations Committee.

Conditions this year were worse than last season; certainly no better in any respect. I concluded the time had come for action, and accordingly I gave the owner of the hotel property notice that recommendation would be made for the cancellation of his franchise, and that the park would only be kept open for motorists bringing in their own equipment. This had the effect of materially improving service for the remainder of the season, but I feel that a change in the operation of this enterprise must be made.

At Mather's request, Oregon Governor Benjamin W. Olcott appointed a nine-member commission in August 1920 to investigate the status of Crater Lake concessions and develop a "practicable plan" for securing improvements. The committee, consisting of businessmen from Portland and Southern Oregon towns, was given a mandate by the governor to take "care of the interests of the present hotel management" and devise "plans for placing the accommodations at the lake on a basis which will be satisfactory to the national park management and to the thousands of tourists who annually visit this natural wonder." It was Mather's hope that with the results of the study funds could be raised in Oregon to purchase the property of the Crater Lake Company and rehabilitate the enterprise, the "parties subscribing the funds to organize and operate in much the same way as similar groups are now organized for the development of the Yosemite and Mount Rainier properties." [8]

In September 1920 the Department of the Interior informed Parkhurst of its intention to have improvements made in the Crater Lake Company facilities. After listing a series of alleged violations of his contract, the department stated its desire to have Parkhurst answer each charge and propose remedial measures to correct each criticism. If his response were "not timely made" or was "not deemed sufficient to overcome these charges," a hearing would be held. If evidence demonstrated that the company had not fulfilled its contract obligations, its lease would be annulled and revoked. [9]

Meanwhile, the Crater Lake Committee appointed by Governor Olcott conducted its investigation under the direction of its chairman, Sydney B. Vincent. The committee investigated each of 26 charges which had been leveled against the company:

1. That the manager of the Crater Lake Hotel and Anna Springs Camp failed in the year 1919 and 1920 to furnish the guests with ample and proper food supplies.

2. That the Crater Lake management failed to furnish first-class accommodations to the traveling public.

3. That he failed to maintain and keep in good repair Crater Lake Lodge and other buildings in connection with the resort.

4. That the leasee failed to complete Crater Lake Lodge prior to1915 and since that year.

5. That the windows of the hotel were not kept in proper adjustment.

6. That suitable and adequate toilet facilities were not provided.

7. That the toilet facilities existent were not properly cared for and were improperly arranged.

8. That sufficient porter and bell boy service was not provided.

9. That all of the bed rooms were not made available for the guests.

10. That proper and clean linen and bed coverings have not been provided.

11. That the bed rooms are not completely or well furnished.

12. That an adequate supply of water was not available at all times.

13. That a sufficient number of boats for the accommodation of the guests was not provided. That guests were not supplied with sufficient information regarding the use of such boats.

14. That the management of the resort was generally lax.

15. That at the time of the visit of the National Editorial Associationin 1919 the visitors were compelled to sleep three and four in aroom.

16. That fire escapes had not been provided.

17. That the lighting system obtaining at the hotel was wholly inadequate.

18. That the taxes due Klamath County by the leasee had not been paid for several years.

19. That the leasee is not and has not been able properly to finance his operations.

20. That fresh milk was not available for the use of guests. available.

21. That horses for the accommodation of tourists were not available.

22. That ice was not to be had at the Lodge during the summer season.

23. That the sale of souvenir, or Crater Lake novelties, was not pushed.

24. That visitors at the Lodge on and about the 4th of July of this year were not all served with meals.

25. That an existing outside fireplace was not properly sheltered from the wind.

26. That garage accommodations were not afforded the guests.

Regarding the accommodations and services provided by the Crater Lake Company, the committee noted that high costs, short seasons, and large crowds made it extremely difficult to bring park concession operations up to the standards desired by Parkhurst himself and others. The committee concluded its report with a sympathetic discussion of the plight facing Parkhurst:

Your Committee has carefully considered all the phases of the situation coming within its knowledge, has read letters of endorsement of Mr. Parkhurst's treatment of his guests and of the general atmosphere at Crater Lake Lodge. Probably our greatest criticism may be directed against the toilet system which prevails at the hotel. We believe that Mr. Parkhurst had made a faithful and earnest effort to make Crater Lake Lodge a resort of merit and note and that he has in a measure met with success, as indicated by the increasing attendance at the resort since 1910. . . . We find that Mr. Parkhurst has received little or no cooperation from any source whatsoever, except banking accommodations. The National Park Service through the Superintendent of the Park has extended numerous small courtesies, but so far as we were able to ascertain the financial burden has been borne by Mr. Parkhurst alone.

It is the understanding of our committee that at other national parks the government has expended considerable sums of money in various ways, not only to improve park conditions, but to provide for the accommodation of guests at these resorts.

Your committee understands that the government has spent something over $100,000 for the installation of an electric lighting system in the Yosemite National Park, but has not spent anything for this, or other developments at Crater Lake Lodge.

In conclusion your committee begs to state that it is its opinion that there is room for great development at Crater Lake; that most of the complaints directed against Mr. Parkhurst might be attributed to the fact that he has not been properly financed and that were he afforded the necessary financial assistance Crater Lake Lodge would become one of the noted resorts of the country. Mr. Parkhurst has almost impoverished himself to keep Crater Lake Lodge going from year to year, making such improvements as his financial capacity would permit. He has invested a large sum of money and should he be retired as lessee, we believe he should be adequately reimbursed for his expenditures of time and money. Mr. Parkhurst is not a hotel man of the modern type, and we believe in some particulars the management has been lax, and that perhaps if satisfactory arrangements could be made for the buying out or other disposal of Mr. Parkhurst that Crater Lake Lodge properly financed might go ahead more rapidly under different management. We say this in all kindness realizing the tremendous burden that one man has had to carry without material help from any source. Mr. Parkhurst is entitled to great credit for what he has accomplished. In all kindness and respect to the Hon. Stephen Mather, your committee begs leave to express the opinion that Mr. Mather expected too much of Mr. Parkhurst under the conditions; also that Mr. Mather has been a little too harsh and abrupt in his handling of the situation. We realize the wonderful work that Mr. Mather has accomplished for the national parks of our country also that carrying the burden of so many national resorts, hampered as he probably is by some of the proverbial red tape of governmental operations, and that the embarrassment caused him by the inadequate toilet and lighting facilities, especially while the congressional party was at Crater Lake, magnified the shortcomings of Mr. Parkhurst's management and precipitated the condition which lead to the appointment of your committee. . . .

We believe it to be the duty of the people of Oregon, either to get behind Mr. Parkhurst financially and otherwise, or in lieu of that, have someone to organize a corporation which will buy out the existing corporation on a fair basis of return to the stockholders and to fairly compensate Mr. Parkhurst for the ten years of nerve racking toil which he has undergone. We also are of the opinion that the government, through Mr. Mather's department, should carry some of the burden of improving the Crater Lake situation, aside from the road work which the Forestry Department is doing. [10]

Through the efforts of Mather a conference of Oregon businessmen was held during the winter of 1920-21 to work out arrangements for the refinancing and reorganization of Crater Lake park concessions. In his annual report for 1921 Director Mather described at length the financial reorganization and subsequent improvement to concession accommodations and services:

The outstanding achievement of the year in Crater Lake National Park was the improvement of hotel accommodations, transportation facilities, and miscellaneous service along progressive lines, thus solving the most serious and aggravating problem that has confronted me in this park since entering upon my present duties. This important accomplishment was brought about by the Crater Lake National Park Co., a new corporation formed and financed by several public-spirited citizens of Portland and other Oregon cities, headed by Mr. Eric V. Hauser. This new corporation leased the Crater Lake properties from the old Crater Lake Co., which originally built the lodge on the rim of the crater, and pioneered in the furnishing of other service, the lease to be effective until March 1, 1922, on or before which date the lessee company may exercise an option to purchase the properties as provided in the agreement of lease. It is confidently expected that the option will be exercised, and that under the new ownership and management the present policies of improvement and development will be continued.

In the agreement of lease covering the change in management of the public utilities, it was provided that the sum of $20,000 was to be expended in the improvement of the properties, this fund to be regarded as a loan to the Crater Lake Co., secured by a first mortgage on its equipment and other personal property, and payable in three equal annual installments if the option to purchase is not exercised, but to be canceled if the option is exercised. The fund, of course, was to be expended by the new company. With this money the new management has completed the Crater Lake Lodge, improved the water and lighting systems, installed necessary sanitary fixtures, erected 30 tent houses or bungalow tents at the lodge and 10 at Anna Spring Camp near headquarters, procured and placed on the lake a launch with a capacity of 40 passengers; and in many other directions provided the means of rendering excellent service and meeting the public demand for proper accommodations in this park.

Mather concluded his remarks on the new concession arrangements by discussing its wide support by Oregon business interests. He noted:

Considering the short season and other serious handicaps under which the new enterprise has been developed, the success that it has achieved has been most remarkable, and has been the subject of widespread favorable comment. The work accomplished has stimulated the pride of the State in the park as nothing else has done. The results of the season are bound to be far-reaching, and I feel very sure that when the properties are finally purchased by the new company, and more funds are needed for further development, additional capital will be freely offered in all sections of the State, thus bringing to the aid of the park the interest and energies of many more such able men as are now identified with this progressive work. Such a consummation would place Crater Lake Park in a position identical with Mount Rainier and Yosemite Parks, which are being improved with funds subscribed from all parts of Washington and California respectively, by business men who are intensely proud of the chief scenic areas of their States, and appreciate their value as playgrounds for the people.

That the support of every section of the State might be gained in this project was anticipated by the organizers of the new company, who conferred with business men of southern Oregon and interested several prominent citizens. Some of these men are now officers and directors of the company and very active in its affairs. Mr. Eric V. Hauser, of Portland, is president of the new corporation; Mr. R.W. Price, of Portland, is the first vice president; Mr. V.H. Vawter, of Medford, is the second vice president and treasurer, and Mr. C.Y. Tengwald, of Medford, is the secretary. [11]

In April 1921 the lodge and other concession operations in the park were placed under the day-to-day management of E.E. Larimore, an experienced hotel manager on the Pacific Coast. The change of management had an immediate impact on lodge operations. On August 29 the Medford Mail Tribune described these changes in atmosphere and efficiency:

In former years everyone was impressed by the natural beauties of Crater Lake, but after the first gasp, there was an awkward pause. It was like entering a beautiful residence, expecting to greet an old friend, but finding no one at home. There was no one at home at Crater Lake inside the lodge or out. After a few "Ohs" and "Ahs" and a leaving of cards, as it were, one was eager to get away.

This year there is a decidedry homelike atmosphere at the lake. One feels it immediately upon entering the lodge. You are not greeted as if you were merely an animated five dollar bill, welcome solely as a contributor to household expenses, but as a human being on a pilgrimage of devotion. Will Steel, the father of Crater Lake, puts this over. He is behind the counter to greet you, not as another customer, but as another candidate for initiation into the Mystic Order of Crater Lake enthusiasts.

Moreover the entire hotel staff is on its toes. They are all new and have the enthusiasm of fresh recruits. Not only is the table excellent, but the service combines beauty and efficiency to a remarkable degree.

At night the guests gather around the fire like a large and happy family. There is music furnished by members of the hotel staff, and there is dancing entered into even by those who climbed Garfield Peak in the afternoon.

Then Will Steel usually gives a little talk on Crater Lake, its history and formation, which is just what the visitors are eager to hear, and about ten o'clock everyone trots off to bed.

It may be merely the difference between good hotel management and no hotel management at all. But there seems to be something more--the creation of atmosphere in it. This appears to be the supreme achievement of the Crater Lake management of 1921. [12]

Park visitation increased by more than 40 percent for a total of 28,617 in 1921 despite the late opening of park roads due to late spring snows. The increase was attributed in part to the concessioner arrangements as well as improvements to the three public campgrounds in the park. Water facilities were installed at the Rim Campground, and toilets were constructed in each of the campgrounds. Some 14,000 persons, or 50 percent of park visitors, used the campgrounds. [13]

The Scenic America Company, a Portland-based firm headed by Fred H. Kiser, opened a photographic studio west of the lodge on August 25, 1921. Prior to the erection of the stone building the studio had operated in a tent. Under the terms of its concession contract the company sold photographic souvenirs, post cards, oil enlargements, and camera supplies. According to Mather, the establishment of this studio brought "to the park permanently the genius and artistic influence" of a man "who knows the national park system as well as anybody in the Northwest, and who for many years has aided this bureau by supplying pictures, by lecturing, and by writing on the parks and other western mountain regions". [14]

In June 1922, just prior to the opening of the tourist season, the Crater Lake National Park Company formally acquired the concession facilities leased to them by the Parkhurst interests the previous year. The lodge was improved, and on July 11 construction was begun on an $80,000 eighty-room addition. Under a two-year subcontract to William T. Lee of Klamath Falls a fleet of six "powerful new seven-passenger [Packard] touring cars" was introduced to provide improved service between the park and Medford and Klamath Falls. A five-year subcontract was let to the Standard Oil Company of California to construct and operate a gasoline service station at Anna Spring, thus filling a long-felt need by the motoring public. [15]

To protect the investment of the new concessioner and to encourage the development of plans for further comprehensive improvements and extensions in accommodations for park visitors a new franchise was granted the Crater Lake National Park Company by the Department of the Interior. The contract, signed on December 7, 1922, but made retroactive to January 1, provided for a twenty-year arrangement to cover hotel, camp, transportation, and other visitor services. While the contract offered "inducements for progressive development of the Crater Lake properties," it also contained, according to NPS Director Mather, "reciprocal obligations on the part of the owner to keep abreast of the demand for increased facilities, in so far as this can be done with due regard to the short season, reasonable return on the investment, and similar considerations." [16]

The detailed provisions of the contract were designed to circumvent problems that had arisen with the former Crater Lake Company. Among other things the contract stated:

Term of the lease to be for twenty years from January 1, 1922, authorizing the Company to establish, maintain and operate in Crater Lake National Park hotels, etc., for the accommodation and entertainment of tourists and others; to install and operate laundries and barber shops, Turkish baths, bath houses, swimming pools; provide facilities for skating, sleighing, skiing and other winter sports; establish and maintain hot houses and gardens; to sell newspapers and other articles of merchandise; also to establish, maintain and operate a transportation service; to maintain for use and hire, row boats on the lake; to conduct a general livery business; to establish and operate lodges; also to establish a dairy service and to operate general merchandise stores.

The new company was given the right to occupy certain portions of the park to maintain its facilities and operate them. All plans for construction were to be approved by the Secretary of the Interior. The company was authorized to use timber, stone, and other building materials taken from the park for construction purposes, establish electric light plants and telephone and telegraph service, and graze horses. Provision was made for the renewal of the contract for a period not to exceed twenty years. The company was allowed to earn annually 6 percent in the value of its physical investment in the park, the 6 percent to be in the nature of a priority and if not earned was to be cumulative. The company was required to submit a schedule of all charges above 50 cents for the approval of the Secretary of the Interior, who could make such modifications as he deemed necessary so long as they were consistent with a reasonable profit on the investment made by the company. Concession employees were required to wear an identification badge, and the Secretary of the Interior was authorized to declare any person unfit or objectionable for employment by the company. [17]

The publicity surrounding the new concessioner and provision of visitor services, together with the removal of snow and opening of park roads by late June, contributed to an increase of visitation of more than fifteen percent in 1922. All told some 31,119 visitors entered the park in 9,429 private automobiles. In addition 995 visitors entered the park via transportation company stages, and 897 entered by other means, thus making the total park visitation 33,011. [18]

NPS Director Mather reported on the increasing popularity of Crater Lake National Park in 1923. With obvious pride in his accomplishments in terms of improving visitor facilities and services he stated:

Park facilities in every way equaled the unprecedented demands upon them. The tourist camps were enlarged early in the season, ample sanitary facilities installed, and additional water supply provided. The operators kept apace similarly, so that at no time were the hotel, transportation, or launch facilities jammed. Early in the season, as it became apparent that visitors preferred accommodations in view of the lake, the lodge management removed the tent houses from Anna Spring to the Rim and were thus able to take care of all demands for lodging. The only difficulty encountered in handling the greatly increased travel was a temporary shortage of water at the Rim, a crisis being avoided by installation of two additional 20,000-gallon storage tanks. . . .

. . . public facilities are in excellent condition and balanced nicely against requirements. With a few exceptions, sanitary provisions and water supply are well ahead of demands, trails are adequate and well maintained, sufficient dockage is provided on the lake, and auto camp grounds are well distributed and were splendidly maintained all season. Firewood has been available in all camp grounds. A number of new signs designed to reduce speeding at critical points were put up and traffic so regulated that no one was injured throughout the entire season, only two minor collisions occurring.

The reaction of visitors to the efforts of the park forces was beyond praise, nearly all being imbued with the finest possible spirit--that splendid spirit that tends to highest development among men and women who gather nightly around camp fires in the mountains.

The visitor facilities and physical improvements alluded to by Mather included the construction of a large combination mess hall and bunk house at Lost Creek for the use of early park visitors entering from the east. A 70-foot log boat landing had been constructed at Wizard Island. Two new flush toilet facilities with lavatories and oil-burning water heaters for hot showers were constructed at each of the campgrounds at the rim and Anna Spring.

An upgraded publicity program for the park was also initiated in 1923. The Southern Pacific Railroad and the Crater Lake National Park Company led the campaign. Superintendent Sparrow contributed to the publicity initiatives by preparing articles for publication in four national periodicals and various newspapers.

The new visitor facilities and the publicity efforts contributed to making 1923 the highest visitation year in Crater Lake's history to date. The total number of visitors increased by some 57 percent to 52,017. The western entrance continued to be the most popular. A new record for the largest single day's visitation through an entrance was established on September 2 with 235 cars carrying 884 visitors entering the park via the western gateway. Visitors came from every state but two, and from such places as Hawaii, Switzerland, and the Netherlands. There was a notable increase of visitors from California, the "number of first entry cars from that State during July equaling first entries from Oregon itself." [19]

Visitation to Crater Lake increased by another 24 percent in 1924 to 64,312. This increase, according to Mather, was the result of four factors: an early opening; the park's location almost midway in the Pacific Coast chain of parks extending from Sequoia to Mount Rainier; the improvement of approach roads; and "increased publicity, largely spontaneous, given by lovers of this Cascade gem."

Improvements to visitor facilities by the Crater Lake National Park Company continued to lure visitors to the park. During 1924 the addition (north annex) to the lodge was completed on the exterior, and 22 of the 85 new rooms were completed and furnished. A new 40-passenger launch was placed in service on the lake, and a new boathouse was constructed on Wizard Island. In addition the Kiser studio added a small wing to provide a one-day film developing and printing service. [20]

During the summer of 1924 the Community House was completed at the Rim Campground. Funds for the structure had originally been intended for construction of a new home for the superintendent, but Thomson diverted the money toward the visitor activity structure. The Community House had a large rustic fireplace and was provided with a Victrola by the Medford "Craters," a booster organization dedicated to promoting park development. The structure became the setting for informal evening gatherings, lectures, dancing, and musical programs, the latter featuring the "Kentucky Rangers" quartet consisting of four seasonal park rangers from that state. [21]

Prior to the 1925 travel season, R.W. Price, who had become president of the Crater Lake National Park Company, began an advertising campaign for the park. The campaign, which took the form of an annual trip that he continued until 1941, consisted of visits to railroad passenger and tour agencies throughout the eastern United States. His annual tours took him from Chicago to Washington, D.C., north to Boston, west to Buffalo and Cleveland, and back to Chicago. [22]

Travel to Crater Lake increased slightly to 65,018 in 1925. Of this total, some 98 percent traveled in their private automobiles. For the first time in its history Crater Lake entertained guests from every state in the union, as well as several foreign countries. This travel increase was significant because the 1925 season was five weeks shorter than that of 1924 because of adverse weather conditions.

Only minor improvements were made to visitor facilities in 1925. These included the completion and furnishing of nine rooms in the lodge, thus bringing its total to 92, eight new rowboats, and a complete sewage-disposal plant. [23]

With the increasing visitation the National Park Service implemented an extensive road sign information program at Crater Lake during the mid-1920s. In 1925, for instance, the park information circular, stated:

As fast as funds are available for that purpose the National Park Service is having standard signs placed along the roads and trails of this park for the information and guidance of the motorists and other visitors that use the park roads and trails.

These signs, in general, consist of information signs, direction signs, elevation signs, and name signs, all of which are of rectangular shape and mounted horizontally; and milepost signs, rectangular in shape but mounted diagonally; all of which usually have dark-green background and white letters, or vice versa; and danger or cautionary signs, most of which are circular in shape and usually have red background and white letters; and comfort station, lavatory, and similar signs, triangular in shape, having dark-green background and white letters. These last signs are so mounted that when pointing downward they designate ladies' accommodations and when pointing upward they designate men's accommodations.

The text on the standard road signs is in sufficiently large type to ordinarily permit their being read by a motorist when traveling at a suitable speed; however, as an additional safeguard, the motorist must always immediately slow down or stop or otherwise fully comply with the injunctions shown on the circular road cautionary signs.

Because of lack of funds, it has not been possible to place cautionary signs at all hazardous places in the roads; therefore the motorist must always have his car under full control, keep to the right, and sound horn when on curves that are blind, and not exceed the speed limit, which is 20 miles per hour on straight, fairly level road and 12 miles per hour on curves, narrow, or steep descending sections of road. [24]

Visitation to Crater Lake continued its general upward trend from 1926 to 1931 with the exception of a slight decrease in 1927, the result o a shortened travel season because of some 51 feet of snow during the winter of 1927-28. During this six-year period visitation nearly doubled from 86,019 in 1926 to 170,284 in 1931, while the number of private automobiles entering the park more than doubled from 26,442 in 1926 to 56,189 in 1931. While the number of private automobiles entering the park increased, the number of persons entering by auto stage declined from 792 in 1926 to 535 in 1931.

Various factors contributed to this major increase in travel to the park. Road improvements both within and outside the park facilitated travel. In 1926 the Cascade line of the Shasta route of the Southern Pacific Railroad, connecting Eugene with Klamath Falls, was completed, thus bringing a rail terminal within about twenty miles of the park. That same year the Crater Lake National Park Company negotiated a fifteen-year contract with the Standard Oil Company to construct and operate a "stone-and-rustic" service station at the junction of Sand Creek and Anna Spring roads at Government Camp, thus providing a more centrally-located station for park visitors. Winter recreation opportunities in the park began receiving attention in 1927 with the commencement of the first annual ski race from Fort Klamath to Crater Lake Lodge and return sponsored by the Fort Klamath Community Club on February 22. Thereafter the ski race and accompanying winter carnival became an annual event, generating considerable interest in winter sports in the park and increasing pressures to keep park roads to the rim open as long as possible during the winter to afford tourists the opportunity of viewing the "beautiful and inspiring spectacle" of the lake in its "winter garb." [25]

The growth of park visitation was encouraged by the continuing development of improved visitor facilities in the rim area. In 1927 Park Service officials and representatives of the Crater Lake National Park Company and the Bureau of Public Roads developed a plan for rim area development. The plan provided that the concessionaire would construct and operate in the next year a cafeteria with a connecting general store for the sale of camping supplies and a group of rental cabins in the campground area away from the rim edge. Other improvements scheduled were an asphalt trail along the edge of the rim the full length of the village area; restoration of the soil between this promenade and the revetment to natural grasses and wildflowers; and construction of a wide parking area alongside a thirty-foot dustless road.

During 1928 the rim area was vastly improved. It was opened at the west boundary by the completion of a new road emerging at the rim edge. From there a new oiled drive led to the new cafeteria/general store and cabin group, campground, and lodge at the opposite end of a half-mile plaza. On each side of the boulevard an 18-foot parking strip was provided for several hundred automobiles. Along the edge of the rim a wide asphalt promenade was built for pedestrians and between this and the log parapet limited parking along the boulevard was an area of varying width graded for plant restoration. The group of fifteen housekeeping cabins was opened on July 15, and the new cafeteria/general store on July 20. A new Crater Wall trail was constructed from the west end of the Rim Campground to the lake "on high standards to permit the use of saddle animals, enabling many thousands to enjoy the lake who were heretofore denied that pleasure by physical incapacity." The trail was opened on July 6 with Secretary of the Interior Ray L. Wilbur leading the first party ever to descend to the lake on horseback. That same year the company added a veranda on the lake side of the lodge, introduced a 35-passenger launch on the lake, and made saddle horses available for rental. [26]

As a result of the rim area development in the 1920s park visitor facilities and accommodations became centered in what was referred to as Rim Village. A Park Service circular for 1930 described the physical development of the village:

A large majority of visitors first reach the rim of the lake at the Rim Village. This is the main focal point of park activities, containing the lodge, post office, cafeteria, general store, studios, a rental cabin group, auto service, emergency mechanical services, ranger station, etc. From the Rim Village a number of the most important trails take off, including the spectacular new trail, just completed, down the crater wall to the lake shore, where launches and rowboats are available for pleasure trips and fishing excursions. This fine trail is 6 feet wide and on a holding grade of 12 per cent, permitting its use by people unaccustomed to much physical effort. For those who prefer not to walk, saddle horses and saddle mules are available for this and other trail trips. The trail to the summit of Garfield Park, directly overlooking the lake and giving a magnificent panorama of the Cascades, also takes off from the Rim Village, as does the trail to the Watchman, and another trail to Anna Spring.

A fine free camp ground, equipped with hot and cold shower baths and modern sanitation, is located here on the rim; its community house, comfortable with fireplace and with a small dance floor, is the center of evening recreation. A near-by cafeteria and general store cares for campers as well as for users of the rental cabins which are grouped near by. [27]

The introduction of modern snow removal equipment in the park during the winter of 1929-30 aided the increasing park visitation. In 1930, for instance, the equipment permitted opening of the park on April 14, the earliest date for travel to be checked in the park's history. The new removal equipment allowed the park to publicize its intention to keep the park open until December, thus affording visitors the opportunity to view the lake throughout the fall season. [28]

The Crater Lake campgrounds became increasingly popular attractions for park visitors during the late 1920s. In 1927, for instance, Superintendent Thomson reported that 70 percent of the park visitors "took care of themselves in one or more of the ten campgrounds." The Rim Campground was the most popular, an average of 300 people using it each night. [29] By 1930 the number of visitors using the three principal park campgrounds were:

| Rim | 5,129 | 14,373 |

| Anna Spring | 568 | 1,829 |

| Lost Creek | 240 | 739 |

5,937 |

16,941 |

In addition a number of visitors used less structured camping places along the roads at White Horse, Cold Springs, and Sun Creek. [30]

Since the mid-1920s medical problems involving visitors and park employees had been referred to Dr. R.E. Green in Medford. With the increase in park visitation, however, it became imperative that a doctor and nurse be stationed in the park during the travel season. Accordingly, a three-year contract was awarded in 1930 to Dr. Fred N. Miller, head of the medical service at the University of Oregon at Eugene, to provide such services at Government Camp from June 15 to September 15 each season. [31]

During 1931 various new visitor facilities and services were introduced that served as further inducements to park travel. These included the introduction of naturalist-conducted boat trips on the lake and automobile caravan tours, launching of a new boat on the lake, construction of twenty new tourist cabins near the cafeteria and new docks at the bottom of the lake trail, location of a new organized campground at White Horse Creek, dedication of the Sinnott Memorial, and development of new trails to Garfield Peak and on Wizard Island. [32]

After more than eight years of operation in the park the Kiser Studio was closed when its concession contract expired on December 31, 1929. As a result of financial difficulties and increasing competition for the photographic souvenir market by the Crater Lake National Park Company, the studio was operated during 1929 by the stockholders of Kiser's, Incorporated, the successor of the Scenic America Company. Although Fred H. Kiser and the Bear Film Company applied for a new studio franchise in 1929, the Park Service did not issue a new permit, and the studio was converted into a visitor contact/information facility in 1930. That year the Crater Lake National Park Company opened a photographic studio in the general store/cafeteria building in addition to a small photo shop in the lodge. [33]

Visitation to Crater Lake slumped to 109,738 in 1932, a decrease of some 35.6 percent compared with the totals for the previous year. Travel by automobile stage totalled 302, a reduction of 42.5 percent from that of 1931. The five main park campgrounds (Rim, Annie Spring, Lost Creek, Cold Spring, and White Horse) were utilized by 11,324 visitors, a drop of 30.7 percent. The volume of business of the park concessioner was cut by approximately 50 percent, and the company's ledgers showed a net loss for the season s operations.

The reduced travel figures were attributed to various causes by Superintendent Solinsky, the chief of which was the national economic downturn. Cold and unusual weather played a significant role in the reduced travel figures. All snowfall records were broken during the winter of 1931-32 as an estimated 85 to 90 feet of snow fell at the rim, and early spring visitors found 20 feet of snow on the level at the rim. Large numbers of tourists from the Pacific Coast states, which traditionally provided the bulk of park visitors, were attracted to Los Angeles for the Olympic Games. [34]

Park visitation continued its downward slide to 96,512 in 1933, but then rebounded to 118,699 in 1934 as the nation's economic woes began to ease. The visitation increase in 1934 was attributed by Acting Superintendent Canfield in part to a "very light winter, the mildest on record since meteorological observations have been maintained throughout the year in the Park." The mild winter allowed access to the park by the public for eleven months compared with the previous maximum of eight. Because of the mild winter and extensive use of the park for winter sports by residents of nearby communities, a winter Ski Carnival was held near Government Camp on March 18, 1934. As a result of the success of this meet Canfield observed that "it is apparent that a great deal of pressure will be brought to bear to keep the Park regularly open for winter consideration." Public interest in keeping the park open in winter was encouraged by articles in national periodicals such as Canfield's "Crater Lake In Winter" published in American Forests in February 1934. [35]

With several exceptions park visitation continued a general upward trend from 1935 to 1941, primarily as a result of improvement in the national economy and year-round operation of the park beginning in the winter of 1935-36. The number of visitors nearly tripled during this period, rising from 107,701 in 1935 to 273,564 in 1941 with an average of some 225,000 during the four years before Pearl Harbor. [36]

Improvement of the national economy and its effects on Crater Lake visitation were apparent by 1935. In July Superintendent Canfield observed:

Travel for the year covered in this report will probably not be up to previous estimates because of a comparatively early winter and a late opening in the spring Once the roads were opened, travel approximated last year's, week by week; but there is an interesting development in that this spring it is apparent that there is a far greater demand for the higher priced accommodations. People are staying longer and spending more money than for several seasons. [37]

During the winter of 1935-36 the highways to the park from Medford and Klamath Falls were kept open, thus making the park accessible to motorists the entire year for the first time in Crater Lake history. Commenting on the year-round operation of the park and its impact on visitation Superintendent Canfield wrote in July 1936:

This [travel increase] is not only due to an increased national park consciousness on the part of the traveling public and apparent improved economic conditions, but due to year around park accessibility. The latter fact is in direct contrast to short seasons, the result of snow blocked roads until late in the spring. Cooperation from the Oregon State Highway Commission in snow removal from approach roads was an important factor in the winter accessibility of the park. Discussions were begun by this office during the past year with the park public utilities operator with the object of formulating definite plans to ultimately offer limited accommodations for winter visitors. Hitherto, no food or lodging has been available, working an inconvenience on visitors. The nearest accommodations are over 20 miles distant. While it is not likely such services will be offered during the next winter, a step forward in the right direction has been realized. . . .

. . . That this [year-round] development was appreciated, was shown by the arrival of many visitors during the snow-covered months to view Crater Lake in its scintillating raiment of winter finery. These visitors, to a large number, took an active interest in amateur winter sports, utilizing slopes for skiing, tobogganing and sleighing. The acquisition of an additional snow plow facilitated the difficult task of maintaining open roads in the face of winter storms, leaving a total snowfall of nearly 50 feet. No accidents marred the success of the winter season.

As a result of the open roads, Crater Lake gained further favorable recognition from the public and press as a winter recreational area. [38]

The increasing winter visitation to Crater Lake continued to attract favorable comment from park management. In July 1937, for instance, Superintendent Canfield observed:

The value of winter accessibility of Crater Lake National Park was again shown during the 1936-37 season when open entrance highways were maintained from Klamath Falls on U.S. Highway 97 and Medford on U.S. Highway 99--both gateway cities. Approximately 23 miles of park highways were involved. The Oregon State Highway Department maintained open roads to the park boundaries in cooperation with the National Park Service.

Up until the acquisition of powerful snowplow equipment, the wonders of Crater Lake during winter months were viewed only by the eyes of persons who skiied or snowshoed over 20 to 23 miles of snow. The park was practically inaccessible from November until late June or July 1. Snow was removed entirely by hand labor, making only a one-way traffic lane possible. The one-way traffic would persist until after the middle of July. It is of important interest to note that nearly 50,000 visitors arrived in the park during the time travel had been impossible in previous years. This total speaks for itself.

Through plowing activity and the urging of the superintendent, the Crater Lake Lodge was enabled to begin extensive interior improvements in May, opening for the public earlier than ever before. Hundreds of visitors took part in amateur snow sports in conjunction with drinking in the beauties of Crater Lake in its white raiment. While no ambitious snow carnivals were encouraged and the open roads were not given general publicity due to lack of accommodations, 39 different states were represented during the height of the winter, as well as a number of foreign countries.

Travel for the year covered in this report not only represents a distinct gain over the preceeding year but set a new all time record of 180,382 visitors. A portion of this increase can be directly attributed to winter accessibility, which first became a definite fact in the 1935-36 season. A major share, of course, can be attributed to an increased national park consciousness and apparently improved economic conditions.

Travel increases observed at Crater Lake were also on record in proportion in other national parks. All types of visitors were on the road. They kept the lodge, housekeeping cabins and cafeteria working almost to capacity, as well as keeping park camp grounds crowded. Both the park administration and the park operator are interestedly watching increased winter use of the park with an eye towards the availability of food and lodging accommodations.

The increasing visitation overtaxed the park campgrounds. Thus, preliminary work was undertaken in 1937 to double the size of the Rim Campground. Of particular concern to park management was the increasing number of house trailers that monopolized camp sites without actually using the stoves, fireplaces, and tables. [39]

The Crater Lake National Park Company made various improvements to its facilities and services in 1936-37 to meet the increasing demands of the growing park visitation. All rooms on the third floor of the lodge were completed, and ten uncompleted rooms on the second floor were finished in 1936. With the completion of the ten rooms the entire second floor was completed. In 1937 the lodge lobby underwent alterations, two 20-passenger buses were added to the stage fleet, and six new rowboats were placed on the lake. At the same time the inadequate heating system of the cafeteria was criticized by Park Service officials. The small housekeeping cabins were also characterized as being inadequate from the "standpoint of appearance," "poorly arranged," "disagreeable to occupy," and lacking "many other customary accommodations that are to be found in the better type of park operator's development." [40]

In July 1938 Ernest P. Leavitt, the new park superintendent, reported on the growing visitation to Crater Lake and its impact on park facilities. He observed that the "new all time record" of 204,725 visitors could be attributed

to winter accessibility, snow conditions favorable to all classes of skiers, better publicity in regard to road and snow conditions in the park, and to the fact that the public could, for the first time, obtain meals in the park during the winter.

He went on to state that in spite

of exceptionally heavy snowfall and prolonged storms in the Crater Lake area (the heaviest winter since 1932-33) the park was kept open for winter travel. Keeping the park open throughout the winter was justified in view of record winter travel and also because it made possible the beginning of summer operations much earlier than would otherwise have been possible. . . . It is also significant that having the park open made possible a considerable through-the-park travel, thereby saving many people the otherwise long and circuitous route in getting between points in the east and west side of the Cascade Mountains. . . .

During the period from December 1, 1937, to April 30, 1938, park personnel conducted a survey to determine why winter visitors came to the park. Of the 13,283 visitors entering the park during that period, 5,922 came for winter sports, while 5,825 were attracted by the scenic beauty of the lake. The remainder made use of park roads for travel between the Rogue River and Klamath valleys. Winter travel showed a wide geographic distribution, visitors coming from 32 states, one territory, and 5 foreign countries.

Aside from winter travel, the number of summer visitors was also increasing, thus crowding visitor facilities. During fiscal year 1938, for instance, peak visitor loads on the Fourth of July and Labor Day weekends crowded to capacity the accommodations afforded at the lodge, housekeeping cabins, cafeteria, and campground. On several other occasions throughout the summer all visitor facilities were crowded.

To keep pace with the rising tourism the Crater Lake National Park Company made improvements to its facilities. In 1938, for instance, various improvements were made to the housing arrangements in the lodge, including the elimination of fire hazards, expansion of launch and rowboat facilities, and installation of a laundry in the basement of the lodge. [41]

Winter use of Crater Lake National Park continued to increase during the late 1930s, thus prompting the Park Service to upgrade its public service, health, and safety standards during the winter months. These efforts, which had been commenced during the winter of 1937-38, were finalized during 1938-39. Thus in April 1939 Superintendent Leavitt reported that the past winter had been the first "where the standards of the National Park Service were met in connection with public service,public health, and public safety." In elaborating on this theme observed:

The increased cost to the government in the past two winters in the operation of Crater Lake National Park has not been due to demands of the public because these demands have been kept to a minimum. The increased costs have been necessitated by the Service's own standards of public service, health, and safety. By public service I mean keeping the roads in reasonably safe condition for winter travel by proper removal of snow, sanding bad areas to a limited extent, and by regular patrols to assist visitors who get into difficulties. Also providing adequate parking space for automobiles. Under the head of public service, we have for the first time this past winter provided modern comfort stations at the rim of Crater Lake and at Park Headquarters. These are electrically lighted and electrically heated and tunnel entrances were built between the plowed out roadway and the doorway to these comfort station buildings. The park never previously had such a service.

Special precautions were taken at the rim of the lake to prevent visitors from slipping on the icy snow within the crater wall and being dashed to pieces on the slopes below. An accident of this kind occurred on Memorial Day two years ago in which a young girl lost her life. During the winter of 1937-38 a section of the rim area opposite the parking space was roped off. This was insufficient. During the past winter a rope was stretched from the Crater Lake Lodge to a point northward beyond the area ordinarily devoted to winter sports activities. Signs and flags were placed on this rope at regular intervals, the signs reading, "Danger, do not pass beyond this point".

Crater Lake had more serious accidents this past winter than ever before due to novices trying ski trails that had been laid out for experts. We had both an expert trail and a novice trail properly signed, and one long trail leading from the rim of the lake to Annie Springs.

The Park Service had to be prepared to handle these accidents when they occurred. It was, therefore, necessary to purchase two toboganns specially equipped for handling basket type stretchers in order to go to the assistance of injured visitors who were usually quite some distance from the road. It was necessary to buy several pairs of skis for the official use of our park rangers. Every member of our organization completed the Red Cross First Aid course and rendered very effective and efficient service whenever accidents occurred.

In addition arrangements had to be made to see that a physician or surgeon was in the park on week ends of heavy travel and prepared to render service in the case of serious accidents. Arrangements were made with the Indian Service to provide necessary narcotics for hypodermics to be kept at the park for use of qualified physicians when necessary.

By contracting our dining hall, visitors have been furnished with regular or short order meals during the past two winters at rates that were reasonable. The food was excellent in quality and well prepared and seasoned.