|

CRATER LAKE

Administrative History |

|

|

VOLUME I PART I: HISTORY OF CRATER LAKE UNTIL ITS DESIGNATION AS A NATIONAL PARK |

CHAPTER THREE:

CRATER LAKE ADMINISTERED BY THE GENERAL LAND OFFICE AS PART OF THE CASCADE RANGE FOREST RESERVE: 1893-1902

A. EMERGENCE OF A NATIONAL CONSERVATION ETHIC

The debate over establishment of Crater Lake National Park was part of a larger movement for preservation of natural resources then going on in the United States. By 1864 three scientific thinkers--Henry David Thoreau, the Massachusetts naturalist-poet-philosopher; George Perkins Marsh, a Vermont lawyer and scholar; and Frederick Law Olmstead, superintendent of the Central Park project in New York City--had articulated the need for conservation and the preservation of our country's natural resources from exploitation by business and settlement. Their writings were the foundation upon which all subsequent conservation proponents built their arguments. Olmstead, in particular, advocated the concept of great "public parks" and was responsible for launching a movement to preserve the giant sequoias in Yosemite Valley from commercial exploitation. As a result of pressure exerted on Congress a law was passed in 1864 that granted Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Grove of Big Trees to the State of California as a state park. This was the first time that any government had set aside public lands purely for the preservation of scenic values. [1]

The "public park" concept involving preservation of important natural features and their management for the benefit of the people circulated throughout the East and Midwest from the mid-1860s onward. As a result of the Washburn-Langford-Doane expedition in 1870 and another expedition led by U.S. Geologist Ferdinand V. Hayden the following year, pressure mounted that Yellowstone should be preserved. On March 1, 1872, President Ulysses S. Grant signed the Yellowstone Park bill into law, thus establishing our first national park by virtue of the fact that it was located in Wyoming Territory and hence under the immediate administration of the federal government. A precedent had been established to reserve and withdraw areas from settlement and set them apart as public parks for the benefit and enjoyment of the people. The Yellowstone Park Act empowered the Secretary of the Interior to protect fish and game from wanton destruction and provide for the preservation and retention in their natural condition of timber, mineral deposits, natural curiosities, and scenic wonders within the park. [2]

Meanwhile; wholesale devastation of timber reserves in the West continued. In 1876 the position of forestry agent in the U.S. Department of Agriculture was established to study the twin problems of timber consumption and preservation of forest lands. Other federal efforts that contributed toward awakening public interest in the diversified natural resources of the West were Hayden's Geological and Geographical Surveys of the Territories of the United States, John Wesley Powell's United States Geographical and Geological Survey of the Rocky Mountain Region, and Lieutenant George Wheeler's Geographical Surveys West of the One Hundredth Meridian. In 1879 these three groups were incorporated into the United States Geological Survey and placed under the Department of the Interior with authorization to conduct all scientific surveys performed by the federal government. [3]

During the 1870s and 1880s a group of intellectuals, including scientists, naturalists, landscape architects, foresters, geologists, and editors of national periodicals, refined the basic concepts of conservation. Through their writings and leadership they made progress in reversing the traditional American attitude toward the utilization of natural resources. One of the most articulate and widely read spokesman for conservation and the national park idea was John Muir, a well-educated Scotsman who campaigned for the preservation of the wilderness and federal control of the forests in the West. His chief concerns were the waste and destruction of forests by lumbermen, cattle grazing, and sheepherding. [4]

As a result of Muir's campaigning, three national parks--Yosemite, Sequoia, and General Grant--were established to preserve the Sierra forests from timbering excesses and overgrazing. The establishing legislation for these parks passed Congress with little debate, primarily as a result of the fact that "scenic nationalism" and "monumentalism" were not in conflict with "materialism" in these areas by 1890. [5]

B. ESTABLISHMENT OF FEDERAL FOREST RESERVES

During the 1870s and 1880s conservationists in the United States focused considerable energy on a movement to repeal the Timber Culture Act of 1873 and the Timber Cutting Act of 1878. At the forefront of this movement were conservationists interested in forestry such as Charles S. Sargent, John Muir, and Robert V. Johnson, aided by the General Land Office of the U.S. Department of the Interior and foresters in the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Considerable fraud was associated with these laws, and as a result much valuable timber land was lost as it fell into the hands of large corporations and timber speculators. The two acts were ostensibly intended to provide for forest conservation. The Timber Culture Act of 1873 authorized any person who kept forty acres of timber land in good condition to acquire title to 160 acres. The minimum tree-growing requirement was reduced to ten acres in 1878. The Timber Cutting Act of 1878, on the other hand, allowed bona fide settlers and miners to cut timber on the public domain free of charge for their own use. [6]

In 1890 a committee of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, with Thomas C. Mendenhall, Superintendent of the U.S. Coastal Geodetic Survey, as chairman, presented President Benjamin Harrison with a petition recommending that a commission be established to ''investigate the necessity of preserving certain parts of the present public forest as requisite for the maintenance of favorable water conditions." The petition further urged that "pending such investigation all timber lands of the United States be withdrawn from sale and provision be made to protect the said lands from theft and ravages by fire, and to supply in a rational manner the local needs of wood and lumber until a permanent system of forest administration be had." [7]

President Harrison and Secretry of the Interior John W. Noble endorsed the proposals. Provisions of the bill to accomplish these ends were drafted by Edward A. Bowers, a special agent and inspector in the General Land Office, with the advice of John Muir and Robert V. Johnson. Bowers' bill was attached as a "rider" to the Sundry Civil Appropriations Bill and passed by Congress without debate. [8]

The Forest Reserve Act (26 Stat. 1095), signed into law by President Harrison on March 3, 1891, repealed the Timber Culture Act of 1873 and the Timber Cutting Act of 1878. Section 24 further provided:

That the President of the United States may, from time to time, set apart and reserve, in any state or territory having public land bearing forests, in any part of the public lands, wholly or in part covered with timber or undergrowth, whether of commercial value or not, as public reservations, and the President shall, by public proclamation, declare the establishment of such reservations, and the limits thereof. [9]

While the law did not define the objectives for setting aside the forest reservations the ostensible purposes, according to the House Committee on Public Lands, were the protection of "forest growth against destruction by fire and ax and preservation of forest conditions upon which water conditions and water flow" were dependent. The new policy was based on the perception "that a forest-cover on slopes and mountains must be maintained to regulate the flow of streams, to prevent erosion, and thereby to maintain favorable conditions in the plains below." The policy of reserving forest land was thus "confined mainly to those localities in which agriculturists" were "dependent upon irrigation." The overriding goal of the reserve policy was "to maintain favorable forest conditions, without, however, excluding the use of these reservations for other purposes." [10]

During the next decade the Department of the Interior refined its policies concerning the objectives and management of forest reserves. By 1902 the objectives had been developed into a broad formal policy statement:

The object of setting land aside for forest reserves is --

1. To protect a growth of timber on land which is not fit to grow other crops and under conditions where no such protection is assured or can be supplied by private persons or local authorities.

2. To keep a growth of vegetation, especially of timber on mountain lands which would otherwise wash and gully. . . .

Forest reserves have been and are created from lands (nearly all mountain lands) unfit for agriculture for reasons of altitude and consequent climate usually reinforced by poverty or insufficiency of soil. These lands generally bear a stand of timber or indicate that they have borne such and are likely to be restocked with forests if protected. Where these mountain forests have not been reserved and have passed into private ownership their history has generally been that of the Northern pineries and other forest areas. They are culled over for whatever will pay the expense of exploitation, the cutting is careless and wasteful, the profits of the timberman small and to the district much smaller. Since this work of denudation is a temporary matter it does little for the permanent improvement of the locality, but leaves behind it the characteristic ruins of abandoned sawmills and the devastated, fire-scorched mountain lands robbed of their forest and fertility alike and doomed for years, in many cases for centuries, to remain as unsightly, barren wastes where the much-needed waters gather unhindered to rush from the mountains and be wasted. To avoid this permanent injury to districts where every drop of water is precious, and where the protective function of the mountain forests, therefore, is of the greatest importance, is the first object of the creation of forest reserves. To husband an immense wealth of timber, to regulate its use, to utilize only the growth of these mountain forests and thereby insure a continued supply of one of the most important materials, is the second object of the reserve policy. [11]

The Forest Reserve Act was hailed as the cornerstone of national conservation policy. It was later characterized by Gifford Pinchot as "the most important legislation in the history of Forestry in America." [12] Benjamin H. Hibbard has commented on its effect in establishing a precedent that all of the public domain was not to be disposed of into private hands, thus reversing the previous course of federal land policy:

Without question the act permitting the withdrawal of public [forest] land from private entry was the most signal act yet performed by Congress in the direction of a national land policy. [13]

President Harrison utilized the new act at once, establishing the Yellowstone Timberland Reserve of 1,250,000 acres on March 30, 1891, as the first national forest reserve. During the remainder of his administration he withdrew some 13,416,710 acres of the public domain, chiefly in California, Oregon, and Wyoming, as forest reserves. [14]

While a great victory had been achieved, it was not yet complete for Congress had not yet granted the authority to protect, administer, and utilize the new forest reserves. Although lumbermen, miners, settlers, and stockmen could no longer obtain legal title to the land located in the national forest reserves, they continued to trespass on public forest land as they had in the past. [15] For instance, in his annual report for 1892 Interior Secretary Noble commented on the need for protection of the new reserves:

These forest reservations should receive protection, either by guards furnished from the Army, as has been done in the Yellowstone National Park, the Sequoia National Park, and elsewhere, or an appropriation should be made to pay custodians and watchmen, so that not only may depredations be detected, but fires, that consume so great a part of our timber, may be prevented. [16]

The problem of protecting the forest reserves was again discussed by Secretary of the Interior Hoke Smith in his annual report for 1893. He observed:

Numerous complaints have been received by the Department of stock men driving their sheep on these reserves, destroying the herbage and setting fire to the trees; and on the 23d of June, the Acting Commissioner of the General Land Office also called the attention of the Department to the necessity for protecting these reserves, urging that details from the Army be secured to look after the same, until Congress could make suitable provision.

Accordingly, the attention of the Secretary of War was directed to the facts in the case, and the request made that, if practicable, officers of the Army, with a suitable number of troops, be detailed to protect the several reservations.

The Acting Secretary of War declined, however, to make the details desired, basing his refusal upon an opinion of the Acting Judge-Advocate-General of the Army to the effect that the employment of troops in such cases and under the circumstances described by the Secretary of the Interior, not being expressly authorized by the Constitution or by act of Congress, would be unlawful.

These reservations remain, therefore, by reason of such action, in the same condition, as far as protection is concerned, as unreserved public lands and are only afforded such protection from trespass and fire as can be furnished with the limited means at the command of the General Land Office. A bill, however, is now pending in Congress which provides adequate means for the protection and management, by details from the Army, etc., of these forest reservations; it has the hearty approval of the Department, and its early enactment as a law is desirable. [17]

C. ESTABLISHMENT OF CASCADE RANGE FOREST RESERVE

While the legislation to provide for adequate protection of the forest reserves languished in Congress, President Benjamin Harrison continued the policy of withdrawing lands from the public domain as national forest reserves. In 1892, the Oregon Alpine Club, headed by William G. Steel, circulated a petition for submission to the president calling for establishment of a forest reserve along the entire crest of the Cascades in Oregon. By the summer of 1892 the petition had received the endorsement of the governor, secretary of state, state printer, auditor, mayor of Portland, and the president and secretary of the Portland Chamber of Commerce.

Accordingly, in July 1892 Secretary of the Interior John W. Noble appointed R.G. Savery, Jr., as special agent of the General Land Office with instructions to report on the proposal. Based on meetings with Oregon officials and travels over the state Savery reported on July 23 "that the future welfare of the State of Oregon demands the withdrawal and protection of said proposed reservation." In support of his recommendation he noted:

The summit of the Cascade Mountains embraces a narrow strip of land running north and south through the State, nearly all of which is unsurveyed and unoccupied. The surface is rough and broken and entirely unfit for cultivation. The altitude ranges from six to twelve thousand feet. Dense forests of very fine timber cover nearly the entire tract. Snow falls to a great depth on these mountains in winter, remaining until late in the summer, and in some places the snow-capped mountains can be seen the year round. . . .

Not only will Western Oregon be greatly benefited by this reservation, but the same facts and conditions can be properly applied to all of that territory lying east of this range of mountains in Oregon. In this proposed reservation are included several points of interest, which in the near future will become places of great interest to the American people. Mt. Hood, a mountain rising to an elevation of nearly thirteen thousand feet, whose snow-capped peak can be seen from nearly every portion of the State the year round, is heavily timbered and is the source of thousands of small streams, and in the immediate future this mountain will become the source of water supply for the city of Portland. The region surrounding this mountain is rugged and elevated and not valuable for agriculture or minerals. There are also included Mt. Pitt, Mt. Scott, Union Peak, Mt. Theilsen, Old Baldy, Diamond Peak, Three Sisters, Black Butte and Mt. Jefferson, all of which are rough, broken and unfit for cultivation.

Besides these mountains, numerous lakes are included, among which is Crater Lake. . . .

This lake, as stated in the petition herewith enclosed, is one of the greatest natural wonders of the world. The surface of the water is 6,239 feet above the level of the sea. Its depth will average two thousand feet. It is entirely surrounded by precipitous walls or cliffs of great height, being at some points nearly two thousand feet. The diameter of this lake is six and one-half miles.

Among the lakes of lesser importance are Diamond Lake, Crescent Lake, Wold's Lake and Bull Run Lake, all of which add to making this proposed reservation include several of the great natural wonders of the world.

Elk, deer, and other noble game of the country, which have been quite plentiful in that country, are partly disappearing, and unless some reservation of this kind is made it is only a question of a few years when they will become entirely extinct.

While he found that most citizens in the state were in favor of the proposed reservation, he reported rumors that sheepherders from eastern Oregon were opposed. He observed that the sheepherders

from the eastern portion of the State would oppose the proposition from the fact that they penetrate deeper into the mountains each year where they find excellent grass on territory formerly burned over for that purpose. The deliberate setting out of fires and consequent destruction of vast bodies of timber cause constant encroachment of sterility of what is now a source of moisture. [18]

On February 17, 1893, the Oregon state legislature added impetus to the campaign for a forest reserve or reserves in the Cascades by adopting a memorial to the president. The gist of the memorial, copies of which were sent to the Secretary of the Interior and the members of the Oregon congressional delegation, read:

First. The immediate establishment of two reservations, viz: one of Mt. Hood, to be called Mt. Hood Reserve, and the other of Crater Lake, to be called Crater Lake Reserve, with such contiguous territory about each as shall seem proper.

Second. The enlargement and extension of each said reservations so as to include the entire crest of the Cascade Mountains in Oregon, with a convenient space on each side thereof, just as soon as the same can be intelligently done after a prompt but careful investigation by the Interior Department, of any vested rights there may be in such territory. [19]

Responding to these petitions President Cleveland on September 28, 1893, issued a proclamation (a copy of which may be seen in Appendix A) establishing the Cascade Range Forest Reserve. In his annual report for 1894 Secretary of the Interior Hoke Smith described the reserve:

The Cascade Range Forest Reserve, Oregon, runs across the State from north to south, embracing the crest of the Cascade Range, including at either end Mount Hood and Crater Lake. The reservation is 234 miles long, with an average width of 30 miles. The area is 7,020 square miles, or 4,492,800 acres. The summit of the Cascade Mountains embraces a narrow strip of land, the altitude ranging from 6,000 to 12,000 feet. Dense forests of very fine timber cover nearly the entire tract. Snow falls to a great depth, remaining until late in the summer, and in some places snow-capped mountains are to be seen the year round. This range can be properly called the watershed of the Pacific coast, and is the source of thousands of small streams tributary to larger ones.

The principal rivers whose head waters are in this reserve are Hood River, Molalla River, the Mckenzie Fork, Middle Fork and Coast Fork of the Willamette River, Metolins River, Deschutes River, Forks of the Umpqua River, Rogue River, and Klamath River from Klamath Lake. There are also numerous lakes and points of interest in the reservation.

This reserve, as stated above, embraces Mount Hood and Crater Lake, points of interest to tourists and others, and which had previously been petitioned for as separate reservations. The reserve was created upon petitions presented by citizens of Portland and of the localities directly affected. [20]

In the same report Smith went on to describe the problems of inadequate appropriations for the reserves. The lack of funds was having a deleterious effect on the policing and protection of the natural resources in the reserves. He observed:

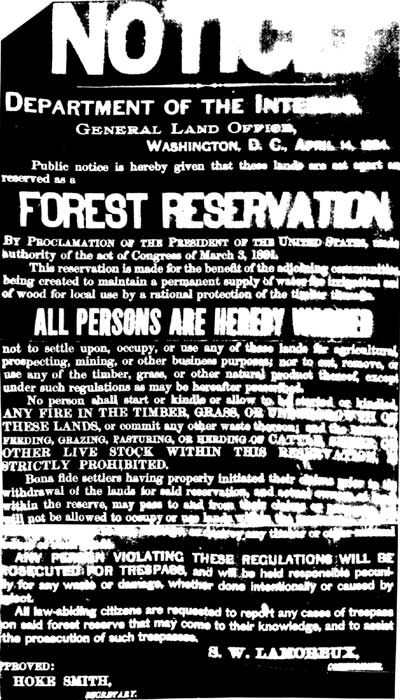

Small appropriations for special agents have thus far made it impossible to detail any of them for the protection of the public forest reserves that have been from time to time created by Presidential proclamation, and which now include some 17,000,000 acres of land. Practically this great mass of reserved lands of this kind are no more protected by the Government than are the unreserved lands of the United States, the sole difference being that they are not subject to entry or other disposal under the public-land laws. Under date of May 12, 1894, this office, with the approval of the Secretary, issued a public notice for posting throughout the forest reserves, calling the attention of the public to the fact that the lands included therein were in a state of reservation, and warning the public against setting fire to the forests or otherwise injuring them, and requesting its aid in checking this evil.

As indicative of the spirit of lawlessness prevailing among those depredating upon these lands, it is significant that, soon after these notices were posted, upon at least one reservation one-half of them were torn down and destroyed. In view of such action, it seems imperative that Congress should appropriate sufficient money to place at least one superintendent upon each of these reservations, and upon the larger ones to provide him with a sufficient number of assistants to enable him to see that the laws and regulations of this Department are respected and that public property shall not be wantonly destroyed. That such action is that of only a few, who are desirous of furthering their personal ends, is apparent from the number of memorials from State legislatures, petitions of governors, and other State officials, State forestry associations, as well as the American Forestry Association, proposing additional forest reserves and laying out their boundaries, with cogent reasons for their establishment. But again, owing to the limited force of special agents, it is ordinarily impossible for this office to detail any of them to make the examinations of the proposed reservations, which are necessary, prior to creating them. [21]

D. ADMINISTRATION OF NATIONAL FOREST RESERVES UNDER THE FOREST

MANAGEMENT ACT OF 1897

Conservationists continued to promote the need for a national forestry system while bills to provide for effective administration and protection of the national forest reserves languished in Congress. As a result of lobbying efforts Congress in 1896 appropriated $25,000 to defray the "expenses of an investigation and report by the National Academy of Sciences on the inauguration of a national forestry policy for the forested lands of the United States." The funds were used to establish a National Forest Commission to be composed of leading scientists and conservationists with Charles S. Sargent as chairman and Gifford Pinchot as secretary. [22]

The National Forest Commission visited the forests on the public lands of the West during the summer of 1896. During the trip the commission members traversed the Cascade Range Forest Reserve. John Muir, one of the commission members, commented on this part of their investigation:

Thence we turned southward and examined the great Cascade Mountain Forest Reserve, going up through it by Klamath Lake to Crater Lake on the summit of the range, and down by way of the Rogue River Valley, noting its marvellous wealth of lodge-pole pine, yellow pine, sugar-pine, mountain-pine, Sitka spruce, incense-cedar, noble silver-fir, and pure forests of the Paton hemlock--the most graceful of evergreens, but, like all the dry woods everywhere, horribly blackened and devastated by devilish fires. [23]

After visiting all of the national forest reservations the National Forest Commission presented its final report to Congress and President William McKinley on May 1, 1897. The report pointed out that, under existing conditions, the United States was unable to protect its timber lands "because the sentiment of a majority of the people in the public land states with regard to the public domain, which they consider the exclusive property of the people of those states and territories, does not sustain the Government in its efforts to protect its own property; juries, when rare indictments can be obtained, almost invariably failing to convict depredators." The report further stated that "civil employees often selected for political reasons and retained in office by political favor, insufficiently paid and without security in their tenure of office, have proven unable to cope with the difficulties of [protecting timber] . . . . The commission also noted that "a study of the forest reserves in their relation to the general development and welfare of the country, shows that the segregations of these great bodies of reserved lands cannot be withdrawn from all occupation and use, and that they must be made to perform their part in the economy of the nation."

The report described the conditions of the forest reserves. The Cascade Range Forest Reserve, according to the commission, had

suffered severely from forest fires which have destroyed a considerable part of its most valuable timber, and from the pasturage of sheep which has been excessive, especially on the dry northern and eastern slopes of the mountains. If timber is taken from this reserve, it is only in small quantities and probably only for the use of actual settlers or the owners of small mines.

The commission found nomadic sheep husbandry to be a serious problem in the Cascades and nearby areas. The report noted:

Nomadic sheep husbandry has already seriously damaged the mountain forests in those States and Territories where it has been largely practiced. In California and western Oregon great bands of sheep, often owned by foreigners, who are temporary residents of this country, are driven in spring into the high Sierras and Cascade ranges. Feeding as they travel from the valleys at the foot of the mountains to the upper alpine meadows, they carry desolation with them. Every blade of grass, the tender, growing shoots of shrubs, and seedling trees are eaten to the ground. The feet of these "hoofed locusts," crossing and recrossing the faces of steep slopes, tread out the plants sheep do not relish and, loosening the forest floor, produce conditions favorable to floods. Their destruction of the undergrowth of the forest and of the sod of alpine meadows hastens the melting of snow in spring and quickens evaporation.

The pasturage of sheep in mountain forests thus increases the floods of early summer, which carry away rapidly the water that under natural conditions would not reach the rivers until late in the season, when it is most needed for irrigation, and by destroying the seedling trees, on which the permanency of forests depends, prevents natural forest reproduction, and therefore ultimately destroys the forests themselves. In California and Oregon the injury to the public domain by illegal pasturage is usually increased by the methods of the shepherds, who now penetrate to the highest and most inaccessible slopes and alpine meadows wherever a blade of grass can grow, and before returning to the valleys in the autumn start fires to uncover the surface of the ground and stimulate the growth of herbage. Unrestricted pasturing of sheep in the Sierras and southern Cascade forests, by preventing their reproduction and increasing the number of fires, must inevitably so change the flow of streams heading in these mountains that they will become worthless for irrigation. [24]

Congress, torn between a militant and well-organized sentiment in the East in favor of forest reservation and scientific forestry management and an irate West fighting against withdrawal and forest protection, was divided on the issue in the wake of the National Forest Commission report. These conflicting views were reflected in the Sundry Civil Appropriation Act (sometimes referred to as the Forest Management Act) of June 4, 1897, The law reaffirmed the power of the president to create reserves and confirmed all reservations created prior to 1897. However, it limited the type of lands to be reserved in the future, stating:

No public forest reservation shall be established, except to improve and protect the forest within the reservation, or for the purpose of securing favorable conditions of water flows, and to furnish a continuous supply of timber for the use and necessities of citizens of the United States; but it is not the purpose or intent of these provisions, or of the Act providing for such reservations, to authorize the inclusion therein of lands more valuable for the mineral therein, or for agricultural purposes, than for forest purposes.

The law granted the basic authority necessary for the federal government to regulate the occupancy and use of the forest reserves and guarantee their protection:

The Secretary of the Interior shall make provisions for the protection against destruction by fire and depredations upon the public forests and forest reservations which may have been set aside or which may be hereafter set aside under the said Act of March third, eighteen hundred and ninety-one, and which may be continued; and he may make such rules and regulations and establish such service as will insure the objects of such reservations, namely, to regulate their occupancy and use and to preserve the forests thereon from destruction; and any violation of the provisions of this Act or such rules and regulations, shall be punished as is provided for in the Act of June fourth, eighteen hundred and eighty-eight, amending section fifty-three hundred and eight-eight of the Revised Statutes of the United States. [25]

In accordance with the provisions of the law Binger Hermann, who had been appointed Commissioner of the General Land Office, prepared rules and regulations for the administration and protection of the forest reserves. These regulations (a copy of which may be seen in Appendix C) were approved by Secretary of the Interior Cornelius N. Bliss on June 30, 1897. Later on March 21, 1898, the rules and regulations were amended (a copy of the amendments may also be seen in Appendix C). [26]

In 1897 Secretary Bliss commented on the effect of the regulations as well as the difficulties encountered in the initial efforts of the department to enforce them. Among other things he observed:

These rules and regulations have been widely distributed, with a view to a better understanding of the subject by the public, and their publication has been secured by the agents of this Office in many of the newspapers of the West as a matter of news .

More general interest is taken in the subject of forest preservation and reservation, and as it is the more inquired into by the people directly affected, the advocates of an efficient forest administration increase in number.

The promulgation of the law and the rules and regulations has, in itself, had a tendency to create greater interest in the matter and to cause the public to observe more closely the regulations and the penalties for the violation thereof.

Since the 1st of July, 1897, under the meager appropriation at the disposal of the Department for the purpose, but six special forest agents and supervisors have been appointed for the purpose of patrolling the forest reserves and enforcing the observance of the regulations. It is needless to say that this force is infinitesimal, considering the magnitude of the work and the territory to be covered. As a region requiring more immediate attention, they were assigned to the reserves in California, Oregon, Washington, Arizona, and New Mexico. it is too early to speak particularly of the work performed by them, but I am justified in saying that their presence in the reservations has already been felt beneficially by a more general observance of the regulations and by the suppression of what might have proved to be very destructive forest fires.

The duties of these forest agents are many, and it goes without saying that the force will have to be very materially increased to fulfill the requirements of the forest-reserve law. It is in the interest of economy and a wise policy to increase the force to make it effective. A well-trained force of 50 or 60 forest agents and patrolmen judiciously distributed through the several States and Territories embracing forest reserves can readily be made the means of preserving millions of dollars' worth of public timber annually from the spoilation of trespassers and destruction by fire at a relatively slight cost to the Government, to say nothing of the importance of forest preservation and the growth and use of merchantable timber for the future generations. [27]

By July 1898 there were thirty forest reservations in the United States embracing an estimated area of 40,719,474 acres. Increased appropriations for fiscal year 1899 enabled the General Land Office to expand its forestry operations and "place a graded force of officers in control of the reserves." The reservations were grouped into eleven districts, each under a forest superintendent. The reserves were placed in immediate charge of forest supervisors with forest rangers under them to patrol the reserves, prevent forest fires and trespass from all sources, and see to the proper cutting and removal of timber.

Instructions were developed for the forest superintendents to guide the administration of the reserves. In regard to forest fires the forest superintendents were directed:

Fire being the paramount danger to which the public forests are exposed, in comparison with which damage from all other sources is insignificant, it is desired that you will see to it that the utmost vigilance and energy are exercised by your forest force to prevent the starting and spread of fires in the reservations under your care.

Each officer should be charged to make the matter of fires in his district the subject of close and careful study, with a view to ascertaining and reporting the chief causes of fires in the different localities and devising means to prevent the same.

They should specially keep a constant watch to prevent fires occurring through the following sources:

1. Hunters, trappers, and other camping parties; more especially those made up of inexperienced persons from towns, who are known to be a fertile source of forest fires.

2. Sheep men, who set out fires to increase pasturage.

3. Prospectors, who frequently set fires to uncover the rock.

4. Parties constructing railroads or making other roadways through the forests.

5. Lumbermen, who should be required to clear the ground of all lops, tops, and other debris resulting from their operations.

The localities specially exposed by reason of settlement, railway construction, lumbering operations, sheep grazing, mining operations, or other causes, should be closely watched, and prompt action taken not only to prevent and extinguish fires, but to bring to justice all parties responsible for fires originating from either carelessness or malicious intent.

The superintendents were instructed "to further report on advisable measures to adopt in devising the most practicable system of patrolling the reservations." Specifically, they were to report on the establishment of patrols and signal stations and telephonic connections between the two. As to sheep grazing the superintendents were "to inquire into and report upon" the "impact of pasturage on the forests," and make recommendations to minimize such negative impacts. [28]

E. CRATER LAKE AND THE CASCADE RANGE FOREST

RESERVE: 1894-1902

While Congress and the Department of the Interior were grappling with forest management issues during the 1890s, Crater Lake and the Cascade Range Forest Reserve received considerable attention from various state and federal government bodies, political interest groups, and scientific experts.

Controversy over sheep grazing in the reserve developed after April 14, 1894, when the federal government took its first official action against such activity in the forest reserves. On that date regulations were issued prohibiting the "driving, feeding, grazing, pasturing, or herding of cattle, sheep or other live stock" in the reserves. Responding to political pressures from eastern Oregon sheepherders, as well as Klamath County settlers, the Oregon state legislature in February 1895 passed a memorial requesting that the portion of the reserve south of township 32, South Willamette Meridian in Klamath County, be opened for "sale, purchase, settlement, and homestead." [29]

By late 1895 the sheepherding interests of eastern Oregon had developed a scheme to reduce the size of the reserve and thus give them access to greater areas of the Cascades for grazing of their flocks. Their petition was included with a letter sent by Senator John H. Mitchell to S.W. Lamoreaux, Commissioner of the General Land Office, on November 30, 1895:

There is a general belief upon the part of the people of the State of Oregon that a grave mistake was made in the proclamation of the President of September 28, 1893, creating the Cascade Range Forest Reserve in that State in this, that entirely too extensive a region of country was included in that reserve, embracing as it does a strip of land from 30 to 60 odd miles wide, perhaps, the whole length of the State. And it is believed that this proclamation should be so modified as to divide the same into two reservations--one of which shall include Mount Hood and all the land North of it in the State of Oregon and all the land in the present reservation for a distance of 25 or 30 miles south of the base of Mount Hood; the other to include Crater Lake in Southern Oregon and the whole of the present reservation in Oregon South of that Lake, and also for a distance of 25 or 30 miles North of the same; and it is my intention to prepare at an early date an application to the President with a view to such modification. . . .

I would suggest that the Northern line be located at a distance of about 30 miles South of the snow line of Mount Hood and the Southern line about 30 miles North of the North shore of Crater lake, and that the whole of the reservation between these lines be released from the reservation and thrown open to settlement. [30]

Several months later on February 10, 1896, Mitchell followed up this letter with another, recommending that the lands in the reserve be subdivided into five separate tracts. These were to be designated the Mount Hood Public Reservation (322,000 acres), the Crater Lake Public Reservation (936,000 acres), and the Mount Jefferson Public Reservation (30,000 acres), with the two remaining tracts (totaling 3,320,000 acres) to be restored to the public domain. He observed that the forest reserve had been created without protest from the Oregon citizenry, because they did not realize the magnitude of the area it would embrace or that it would exclude from further settlement vast areas of land which he claimed were valuable for agricultural and mining purposes. The sheepherders of eastern Oregon were feeling the economic pinch by having their flocks of more than 400,000 sheep excluded from the eastern slopes of the Cascades for summer grazing.

To counter these proposals Steel and other like-minded conservationists in Oregon put up a stiff lobbying effort with President Cleveland and Secretary of the Interior Smith. On March 6 General Land Office Commissioner Lamoreaux responded to Mitchell with the support of Cleveland by observing:

I have the honor to report that the creation of the "Cascade Range Forest Reserve'' was recommended by the ''Oregon Alpine Club," endorsed by various State, City and Boards of Trade officers, and others, and by a Special Agent of this office after an apparently careful and thorough personal investigation into all of the facts and circumstances involved, who in his report states that the citizens generally are unanimously in favor of the reserve being made.

In view of these facts of record, I do not feel warranted in recommending the sub-dividing of the reserve and the restoration to the public domain of nearly three-fourths of the area embraced therein, without first having a careful and thorough field examination made, by competent and reliable special agents, to ascertain the exact portions of the reserve which are valuable for agricultural or mining purposes, and should be open to entry or location; and as such an examination would involve the services of not less than three special agents for several months, at a heavy expense, I do not feel justified in ordering such an examination to be made unless so directed by the Department. [31]

The lobbying efforts led by Steel against the potential breakup of the Cascade Range Forest Reserve were channeled through the Mazamas, a mountaineering club that he had organized in 1894. A preliminary organization was formed and on July 17, 1894, some 350 persons met at Steel's ranch on the south slope of Mount Hood to hold a campfire. Two days later the club, named after a vanishing species of mountain goat, was formally established on the summit of Mount Hood by some 197 persons who had participated in the ascent. Thereafter, Steel used the club as a vehicle to champion the preservation of the forest reserve against the depredations of timber companies, sheepherders, and land developers. Representing the executive council of the Mazamas, Steel went to Washington to urge Congress and Department of the Interior officials to take more stringent measures to protect the natural resources and scenery of the reserve.

In an attempt to promote preservation of the reserve the Mazamas at Steel's suggestion held a summer outing and mountain-climbing excursion at Crater Lake in August 1896. The trip had the nature of a scientific expedition, since a number of professional men were invited to join the group. These included C. Hart Merriam, chief of the U.S. Biological Survey; J.S. Diller, geologist of the U.S. Geological Survey; Frederick V. Colville, chief botanist of the U.S. Department of Agriculture; and BartonW. Evermann, an icthyologist with the U.S. Fish Commission. Some fifty Mazamas joined these men on the crater rim in mid-August, along with several hundred individuals traveling by wagon and on foot from Ashland, Medford, Klamath Falls, the Fort Klamath Indian Reservation, and the nearby army post at Fort Klamath. Guided nature walks and campfire lectures by the scientists on the flora, fauna, and geology of the region occupied the group's time. A meeting of the executive committee of the Mazamas was held in the crater of Wizard Island. The excursion culminated in the christening of "Mount Mazama," the mountain containing Crater Lake, with appropriate ceremonies on August 21. [32]

The most important result of the excursion was that each of the scientists eventually recommended passage of a bill creating Crater Lake as a national park. Their arguments were made on the basis that the area was a natural wonder favorably situated for a healthful and instructive pleasure resort; potentially valuable for scientific study; a potential contributor to the economic prosperity of the region; and too susceptible to forest fires and worthy of greater care than it was receiving as a forest reserve. [33]

Following the 1896 excursion, the Mazamas began publication of a periodical Mazama that avidly supported national park status for Crater Lake. In 1897 Earl Morse Wilbur published an article in the periodical heralding the lake as one of "the seven greatest scenic wonders of the United States." In the article he described the three main routes to the relatively inaccessible lake. The shortest route led from the Southern Pacific Railroad at Medford and followed up the Rogue River Valley. A second route, known as "the Dead Indian Road," proceeded from the railroad at Ashland, passing by the Lake of the Woods and Pelican Bay on Klamath Lake. The third route left the railroad at Ager, California, and proceeded through Klamath Falls to Fort Klamath where it joined the Dead Indian Road. Wilbur went on to list four things that needed to be done to make Crater Lake a more popular resort:

But to make Crater Lake more popular as a resort for tourists and other visitors, much must yet be done to make it more easy to go there and more comfortable to stay. If it had the improved turnpikes, the easy stages, and the comfortable hotels which have made it easy for visitors to enjoy the grandeur of the Yosemite Valley without great fatigue or discomfort, Crater Lake would gradually and rapidly become recognized as Yosemite's great rival on the Pacific Coast. When the routes of approach have been improved, when a plain but comfortable hotel has been built, when an elevator has been constructed so that one may descend to the water without great exertion, and when a steam launch has been placed on the Lake, the four things will have been done which must be done before Crater Lake can expect to be visited by any considerable number of people from a distance. Perhaps the first step in this direction would be to have the Lake and its vicinity set aside as a National Park. . . . [34]

During the August 1896 expedition to Crater Lake Barton W. Evermann conducted research for the U.S. Fish Commission, the results of which were published the following year. While the lake was found to contain no fish, he reported favorably on the quality of the water and its potential for fish food. He noted that small crustaceans flourished in the water and salamanders occurred in abundance along the shore. Several larval insects and one species of mollusk were also found. He noted that the level of the lake sank at the rate of one inch every five to six days, depending on weather conditions. The temperature of the water at different depths was taken as follows:

Surface - 60°

Depth of 555 feet - 39°

Depth of 1,043 feet - 41°

Depth of 1,623 feet (bottom) - 46°

While the increase of temperature with the depth suggested "that the bottom" might "yet be warm from volcanic heat," it was determined that further observations were needed to "establish such an abnormal relation of temperatures in a body of water." [35]

In July 1897 an article appeared in the Annual Report of the Smithsonian Institution describing the various scientific studies that had been conducted at Crater Lake. J.S. Diller, an employee of the U.S. Geological Survey, discussed the various geographical and geological features of the lake. Among his glowing observations which prompted him to call for national park status for Crater Lake were:

Aside from its attractive scenic features, Crater Lake affords one of the most interesting and instructive fields for the study of volcanic geology to be found anywhere in the world. Considered in all its aspects, it ranks with the Grand Canyon of the Colorado, the Yosemite Valley, and the Falls of Niagara, and it is interesting to note that a bill has been introduced in Congress to make it a national park for the pleasure and instruction of the people. [36]

In January 1898 Frederick V. Colville, chief botanist of the Department of Agriculture, submitted a report on sheep grazing in the Cascade Range Forest Reserve. The investigation was performed in response to a request by the Department of the Interior for a disinterested study in view of the bitter controversy that had been raging over sheep grazing in the reserve. During the summer of 1896 several sheepherders and owners who were grazing sheep on the reserve were arrested under special instructions from the Attorney General of the United States. Later "these cases assumed the form of civil instead of criminal proceedings," and on September 3 suit was brought in the U.S. District Court of Oregon against several owners to enjoin them from grazing within the reserve. In May 1897, the Attorney General, in view of the expected passage of the Forest Management Act, issued instructions that the injunction suits be discontinued. Thus, subsequent to the passage of the act and the formulation of comprehensive rules and regulations the investigation by Colville was initiated.

After studying the sheep grazing problem in the reserve, Colville rejected the two proposals that had been recommended as remedial measures--the total exclusion of sheep and the abolition of the reserve. Instead he proposed ten recommendations that should be taken at once "to save and perpetuate the timber supply and the water supply of middle Oregon:"

1 . Exclude sheep from specified areas about Mount Hood and Crater Lake.

2. Limit the sheep to be grazed in the reserve to a specified number, based on the number customarily grazed there.

3. Issue five-year permits allowing an owner to graze on a specified tract, limiting the number of sheep to be grazed on that tract, and giving the owner the exclusive grazing right.

4. Require as a condition of each permit that the owner use every effort to prevent and to extinguish fires on his tract, and report in full the cause, extent, and other circumstances connected with each fire.

5. Reserve the right to terminate a permit immediately if convinced that an owner is not showing good faith in the protection of the forests.

6. In the allotment of tracts secure the cooperation of the wool-growers association of Crook, Sherman, and Wasco counties through a commission of three stockmen, who shall receive written applications for range, adjudicate them, and make recommendations, these recommendations to be reviewed by the forest officer and finally passed upon by the Secretary of the Interior.

7. Ask the county associations to bear the expenses of the commission.

8. Charge the cost of administration of the system to the owners in the form of fees for the permits.

9. If the woolgrowers decline to accept and to cooperate in the proposed system, exclude sheep absolutely from the reserve.

10. If after five years' trial of the system forest fires continue unchecked, exclude sheep thereafter from the reserve.

Relative to the area around Crater Lake and Mount Hood that he wished to see closed to sheep grazing, Colville stated:

The first step toward a satisfactory system of sheep-grazing regulations in the Cascade Reserve is to provide absolute protection for those places which the people of the State require as public resorts or for reservoir purposes. The grandeur of the natural scenery of the Cascades is coming to be better known. Even before the forest reserve was created a movement was on foot to have the Mount Hood region and the Crater Lake region set aside as national parks, and since the reserve was created the eminent desirability and propriety of the earlier movement has been clearly recognized, both in the continued efforts of the people to keep sheep from grazing in these regions and in the concession in the petition of the sheep owners that if the Cascade Reserve as a whole be abolished the Crater Lake and Mount Hood regions be maintained as smaller and separate reserves on which sheep be not allowed to graze. . . .

In terms of how much land should be included in the closed area at Crater Lake, he recommended:

After going twice carefully over the ground at Crater Lake and consulting with various men well informed on the subject, especially Capt. O.C. Applegate, of Klamath Falls, I question whether a better area can be adopted than that covered by the special Crater Lake contour map, published by the United States Geological Survey, which extends from longitude 122° to 122° 15', and from latitude 42° 50' to 43° 04'. At present no sheep are grazed in the vicinity of Crater Lake, but for a few years up to and including 1896 a small amount of summer grazing was carried on in the watershed of Anna Creek and that of the upper Rogue River. [37]

In 1899 some of the recommendations of the Colville study were implemented. Upon the recommendation of the General Land Office the Secretary of the Interior approved permits to graze a limited number of sheep within restricted areas of the Cascade Range Forest Reserve. [38]

While the sheepherding controversy continued in the reserve Crater Lake received increasing attention in national periodicals. The thrust of these articles was for greater protection of the reserve and national park designation for Crater Lake. One such article appeared in the February 17, 1898, issue of Nature. The author described the scenic beauty and relative inaccessibility of the lake:

Crater Lake is situated nearly in 43° N. and 122° W. It may be reached from several stations on the railway between Portland, Oregon, and San Francisco, by roads, usually bad, and as yet there is no house of any kind near its shore. Leaving the Southern Pacific Railway at Medford, one may reach it by 85 miles of road up the Rogue River valley. From Ashland a road of 95 miles must be traversed; but the best road--one which is practicable for bicycles--is from Ager, Cal., past the deserted Fort Klamath, a distance of 116 miles. The whole country is covered with dense coniferous forest. In approaching the lake, there is a steep climb for about three miles; then the forest-clad mountain slope gives place to a nearly level plateau, carpeted in autumn with flowers, across which one walks a few hundred yards with nothing to see, until suddenly a precipice of 900 feet yawns at one's very feet, and deep below the dazzling blue water of Crater Lake spreads far and wide. The weird grandeur of the scene accounts to the full for the superstitious awe with which the Indians of the district regard the lake. [39]

In the aftermath of the Forest Management Act, which made provision for the survey of the forest reserves, the U.S. Senate passed a resolution on February 28, 1898, "calling on the Secretary of the Interior for a report on the survey of the forest reserves' by the U.S. Geological Survey. The summary section of the report, which was devoted to a description of the resources and activities in the Cascade Range Forest Reserve stated that it consisted of 4,492,800 acres, of which 461,920 were railroad land. Some 95 percent of the reserve was forested with 75 percent "marked by fire" and 90 percent "badly burned." Accordingly, a force of two rangers, five forest guards, and thirty fire watchers was recommended for the reserve. Furthermore the report contained the following data on the reserve:

A rugged mountainous region, densely timbered on the western slope, with much open land cleared by fire, and suitable for grazing.

Fire has done, and is still doing, very serious injury.

Irrigation is but little practiced on either slope.

Mining has little present or prospective importance.

Agriculture can attain little development within the reserve.

The grazing of sheep should be permitted tentatively and under careful restrictions.

The commercial development of this reserve is not demanded for the present. [40]

During 1900-01 various boundary changes were made to the Cascade Range Forest Reserve. On October 9, 1899, citizens of Wasco County submitted the following petition to the General Land Office:

We ask that you extend the reserve, and include within its borders the line of townships adjoining it on the east, or, in other words, we pray you that the east line of the Cascade Forest Reserve be moved 6 miles farther east than at present, between the East Fork of Hood River on the north and White River on the south, and that all of township 1 north of range 11 east of the Willamette meridian also be included in said forest reserve, and that all herded stock be excluded therefrom.

After several studies of the question were conducted by Forest Superintendent S.B. Ormsby a presidential proclamation was issued on July 1, 1901, adding 142,080 acres to the reserve. This addition included most of the land requested by the Wasco County citizens, but excluded "township 1 north, range 11 east, and the north 1/2 of township 1 south" because there were many permanent settlers on those lands. At the recommendation of Ormsby the proclamation included the addition of "township 5 south, ranges 9 and 10 east, and the strip of land lying directly south thereof and extending to the north line of the Warm Springs Indian Reservation."

On June 29, 1900, two townships comprising 46,080 acres were eliminated from the reserve by executive order. Townships 22 and 23 south, range 9 east on the eastern border of the reserve were eliminated on behalf of ranchers and sheep owners who prior to the creation of the reserve had established homes and made improvements on their lands. The townships were deemed nonessential to forest usage and water conservation purposes, their primary value being derived from agricultural utilization. As they were on the border of the reserve, it was determined that they could be eliminated without affecting the integrity or obstructing the control of the reservation. [41]

APPENDIX A:

Proclamation No. 6

(No. 6)

By the President of the United States of America

A PROCLAMATION

|

September 28, 1893 Preamble Vol. 26 P. 1103 |

Whereas, it is provided by section twenty-four of the Act of Congress, approved March third, eighteen hundred and ninety-one, entitled, "An act to repeal timber-culture laws, and for other purposes," "That the President of the United States may, from time to time, set apart and reserve, in any State or Territory having public land bearing forests, in any part of the public lands wholly or in part covered with timber or undergrowth, whether of commercial value or not, as public reservations, and the President shall, by public proclamation, declare the establishment of such reservations and the limits thereof;" And Whereas, the public lands in the State of Oregon, within the limits hereinafter described, are in part covered with timber, and it appears that the public good would be promoted by setting apart and reserving said lands as a public reservation. |

| Forest reservation Oregon |

Now, Therefore, I, Grover Cleveland, President of the United States, by virtue of the power in me vested by section twenty-four of the aforesaid Act of Congress, do hereby make known and proclaim that there is hereby reserved from entry or settlement and set apart as a Public Reservation, all those certain tracts, pieces or parcels of land lying and being situate in the State of Oregon, and particularly described as follows: to wit: |

| Boundaries |

Beginning at the meander corner at the intersection of the range line between Ranges six (6) and seven (7) East, Township two (2) North, Willamette Meridian, Oregon, with the mean high-water-mark on the south bank of the Columbia River in said State; thence north-easterly along said mean high-water-mark to its intersection with the township line between townships two (2) and three (3) North; thence easterly along said township line to the north-east corner of Township Two (2) North, Range eight (8) East; thence southerly along the range line between Ranges eight (8) and nine (9) East, to the south-west corner of Township two (2) North, Range nine (9) East, thence westerly along the township line between Townships one (1) and two (2) North, to the north-west corner of Township one (1) North, Range nine (9) East; thence southerly along the range line between Ranges eight (8) and nine (9) East; to the southwest corner of Township one (1) North, Range nine (9) East; thence easterly along the Base Line to the northeast corner of Township one (1) South, Range ten (10) East; thence southerly along the range line between Ranges ten (10) and eleven (11) East, to the southeast corner of Township four (4) South, Range ten (10) East; thence westerly along the Township line between Townships four (4) and five (5) South, to the south-west corner of Township four (4) South, Range nine (9) East; thence southerly along the west boundary of Township five (5) South; Range nine (9) East, to its intersection with the west boundary of the Warm Springs Indian Reservation; thence south-westerly along said Indian reservation boundary to the south-west corner of said reservation; thence south-easterly along the south boundary of said Indian reservation to a point on the north line of Section three (3) township twelve (12) South, Range nine (9) East, where said boundary crosses the township line between Townships eleven (11) and twelve (12) South, Range nine (9) East; thence easterly to the northeast corner of Township twelve (12) South, Range nine (9) East; thence southerly along the range line between Ranges nine (9) and ten (10) east, to the south-east corner of Township thirteen (13) South, Range nine (9) East; thence westerly along the Third (3rd) Standard Parallel South, to the northeast corner of Township fourteen (14) South, Range nine (9) East; thence southerly along the range line between Ranges nine (9) and ten (10) East, to the south-east corner of Township fifteen (15) South, Range nine (9) East; thence easterly along the Third (3rd) Standard Parallel South, to the north-east corner of Township sixteen (16) South, Range nine (9) East; thence southerly along the range line between Ranges nine (9) and ten (10) East, to the south-east corner of Township twenty (20) South, Range nine (9) East; thence easterly along the Fourth (4th) Standard Parallel South, to the north-east corner of Township twenty one (21) South, Range nine (9) East; thence southerly along the range line between Ranges nine (9) and ten (10) East, to the south-east corner of Township Twenty-three South, Range nine (9) East; thence westerly along the township line between Townships twenty-three (23) and twenty-four (24) South, to the southeast corner of Township twenty-three (23) South, Range six (6) East; thence southerly along the range line between Ranges six (6) and seven (7) East to the southwest corner of Township twenty-five (25) South, Range seven (7) East; thence westerly along the Fifth (5th) Standard Parallel South, to the point for the north-west corner of Township twenty six (26) South, Range seven East; thence southerly along the surveyed and unsurveyed west boundaries of Townships twenty six (26) twenty seven (27), twenty-eight (28) twenty-nine (29) and thirty (30) South, to the southwest corner of Township thirty (30) South, Range seven (7) East; thence westerly along the unsurveyed Sixth (6th) Standard Parallel South, to the point for the north-west corner of Township thirty-one (31) South, Range seven and one half (7-1/2) East; thence southerly along the surveyed and unsurveyed west boundaries of ownerships thirty one (31) thirty-two (32) and thirty three (33) South, Range seven and one half (7-1/2) East, to the south-west corner of Township thirty three (33) South, Range seven and one half (7-1/2) East; thence easterly along the township line between Townships thirty-three (33) and thirty-four (34) South to the north-east corner of Township thirty-four (34) South, Range six (6) East; thence southerly along the east boundaries of Townships thirty four (34) and thirty-five (35) South, Range six (6) East, to the point of intersection of the east boundary of Township thirty-five (35) South, Range six (6) East, with the west shore of Upper Klamath Lake; thence along said shore of said lake to its intersecion with the range line between Ranges (6) and seven (7) East, in Township thirty-six (36) South; thence southerly along the range line between Ranges six (6) and seven (7) East, to the southeast corner of Township thirty-seven (37) and thirty eight (38) South to the south-west corner of Township thirty-seven (37) South, Range four (4) East; thence northerly along the range line between Ranges three (3) and four (4) East, to the north-west corner of Township thirty six (36) South, Range four (4) East; thence easterly along the Eighth (8th) Standard Parallel South, to the south-west corner of Township thirty five (35) South, Range four (4) East; thence northerly along the range line between Range 3 & Range four (4) East; to the southwest corner of Township thirty-one (31) South, Range four (4); thence westerly along the township line between Townships thirty-one (31) and thirty-two (32) South, to the southwest corner of Township thirty one (31) South, Range one (1) East; thence northerly along the surveyed and unsurveyed Willamette Meridian to the northwest corner of Township twenty (20) South, Range one (1) East; thence easterly along the township line between Townships nineteen (19) and twenty (20) South, Range (1) East; thence northerly along the range line between Ranges one (1) and two (2) East, to the northwest corner of Township eighteen (18) South, Range two (2) East; thence easterly along the township line between Townships seventeen (17) and eighteen (18) South, to the south-east corner of Township seventeen (17) South, Range two (2) East; thence northerly along the range line between Ranges two (2) and three (3) East, to the south-west corner of Township seventeen (17) South, Range three (3) East; thence easterly along the surveyed and unsurveyed township line between Townships seventeen (17) and eighteen (18) South, to the point for the southeast corner of Township seventeen (17) South, Range four (4) East; thence northerly along the surveyed and unsurveyed range line between Ranges four (4) and five (5) East, subject to the proper easterly or westerly offsets on the Third (3rd), Second (2nd) and First (1st) Standard Parallels South, to the northwest corner of Township five (5) South, Range Five (5) East; thence easterly along the township line between Townships four (4) and five (5) South, to the southeast corner of Township four (4) South, Range six (6) East; thence northerly along the range line between Ranges six and seven (7) East to the north-west corner of Township four (4) South, Range seven (7) East; thence easterly along the township line between Townships three (3) and (4) South, to the southwest corner of Section thirty-four (34), Township three (3) South, Range seven (7) East; thence northerly along the surveyed and unsurveyed section line between Sections thirty-three (33), twenty-one (21) and twenty two (22), fifteen (15) and sixteen (16), nine (9) and ten (10) and three (3) and four (4), to the northwest corner of Section three (3) of said Township and Range; thence easterly along the surveyed and unsurveyed township line between Townships two (2) and three (3) South, to the point for the southeast corner of Township two (2) South, Range eight (8) East; thence northerly along the unsurveyed range line between Ranges eight (8) and nine (9) East, to the southeast corner of Township one (1) South, Range eight (8) East; thence westerly along the township line between Townships one (1) and two (2) South, to the southeast corner of Section thirty-four, Township one (1) South, Range eight (8) East; thence northerly along the section line between Sections thirty-four (34) and thirty five (35) twenty-six (26) and twenty-seven (27) and twenty two (22) and twenty three (23) to the north-east corner of Section twenty-two (22) thence westerly along the section line between Sections fifteen (15) and twenty-two (22) to the south-east corner of Section sixteen (16); thence northerly on the section line between Sections fifteen (15) and sixteen (16) to the point for the northeast corner of Section sixteen (16); thence westerly along the section line between Sections nine (9) and sixteen (16) to the southeast corner of Section eight (8); thence northerly along the section line between Sections eight (8) and nine (9) and four (4) and five (5) to the northwest corner of Section four (4); Township one (1) South, Range eight (8) East; thence along the unsurveyed section lines northerly to the point for the northeast corner of Section thirty-three (33) westerly to the point for the north-east corner of Section thirty-two (32), northerly to the point for the northeast corner of Section eight (8), westerly to the point for the south-west corner of Section six (6); thence northerly along the unsurveyed range line between Ranges seven (7) and eight (8) East, to the point for the northwest corner of Township one (1) North, Range eight (8) East; thence westerly along the unsurveyed township line between Townships one (1) and two (2) North, to the north-west corner of Township one (1) North Range seven (7) East; thence northerly along the surveyed and unsurveyed range line between Ranges six (6) and seven (7) East, to the meander corner at its intersection with the mean high water mark on the south bank of the Columbia River, the place of beginning. Excepting from the force and effect of this proclamation all lands which may have been, prior to the date hereof, embraced in any legal entry or covered by any lawful filing duly of record in the proper United States Land Office, or upon which any valid settlement has been made pursuant to law, and the statutory period within which to make entry or filing of record has not expired; and all mining claims duly located and held according to the laws of the United States and rules and regulations not in conflict therewith; Provided that this exception shall not continue to apply to any particular tract of land unless the entryman, settler or claimant continues to comply with the law under which the entry, filing, settlement or location was made. Warning is hereby expressly given to all persons not to enter or make settlement upon the tract of land reserved by this proclamation. In witness whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed. Done at the City of Washington, this twenty-eighth day of September, in the year of our Lord, one thousand eight hundred and ninety three, and of the Independence of the United States, the one hundred and eighteenth.

Grover Cleveland |

Steel Scrapbooks, Forest Reserves, No. 24, Vol. I, Museum Collection, Crater Lake National Park.

APPENDIX B:

Steel Scrapbooks, Forest Reserves, No. 24, Vol. I, Museum Collection, Crater Lake National Park.

APPENDIX C:

Rules and Regulations Governing Forest Reserves Established Under Section 24 of the Act of March 3, 1891 (26 Stats., 1095).

[CIRCULAR.]

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR,

GENERAL LAND OFFICE,

Washington, D. C., June 30, 1897.

1. Under the authority vested in the Secretary of the Interior by the act of Congress, approved June 4, 1897, entitled "An act making appropriations for sundry civil expenses of the Government for the fiscal year ending June thirtieth, eighteen hundred and ninety-eight, and for other purposes," to make such rules and regulations and establish such service as will insure the objects for which forest reservations are created under section 24 of the act of March 3, 1891. (26 Stats., 1095), the following rules and regulations are hereby prescribed and promulgated:

OBJECT OF FOREST RESERVATION.

2. Public forest reservations are established to protect and improve the forests for the purpose of securing a permanent supply of timber for the people and insuring conditions favorable to continuous water flow.

3. It is the intention to exclude from these reservations, as far as possible, lands that are more valuable for the mineral therein, or for agriculture, than for forest purposes; and where such lands are embraced within the boundaries of a reservation, they may be restored to settlement, location, and entry.

PENALTIES FOR VIOLATION OF LAW AND REGULATIONS.

4. The law under which these regulations are made provides that any violation of the provisions thereof, or of any rules and regulations thereunder, shall be punished as is provided for in the act of June 4,1888 (25 Stats, 166), amending section 5388 of the Revised Statutes, which reads as follows:

That section fifty-three hundred and eighty-eight of the Revised Statutes of the United States be amended so as to read as follows: "Every person who unlawfully cuts, or aids or is employed in unlawfully cutting, or wantonly destroys or procures to be wantonly destroyed, any timber standing upon the land of the United States which, in pursuance of law, may be reserved or purchased for military or other purposes, or upon any Indian reservation, or lands belonging to or occupied by any tribe of Indians under authority of the United States, shall pay a fine of not more than five hundred dollars or be imprisoned not more than twelve months, or both, in the discretion of the court."

This provision is additional to the penalties now existing in respect to punishment for depredations on the public timber. The Government has also all the common-law civil remedies, whether for the prevention redress of injuries which individuals possess.

5. The act of February 24, 1897 (29 Stats., 594), entitled "An act to prevent forest fires on the public domain," provides:

That any person who shall wilfully or maliciously set on fire, or cause to be set on fire, any timber, underbrush, or grass upon the public domain, or shall carelessly or negligently leave or suffer fire to burn unattended near any timber or other inflammable material, shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, and upon conviction thereof in any district court of the United States having jurisdiction of the same, shall be fined in a sum not more than five thousand dollars or be imprisoned for a term of not more than two years, or both.

SEC. 2. That any person who shall build a camp fire, or other fire, in or near any forest, timber, or other inflammable material upon the public domain, shall, before breaking camp or leaving said fire, totally extinguish the same. Any person failing to do so shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, and upon conviction thereof in any district court of the United States having jurisdiction of the same, shall be fined in a sum not more than one thousand dollars, or be imprisoned for a term of not more than one year, or both.

SEC. 3. That in all cases arising under this act the fines collected shall be paid into the public-school fund of the county in which the lands where the offense was committed are situate.

Large areas of the public forests are annually destroyed by fire, originating in many instances through the carelessness of prospectors, campers, hunters, sheep herders, and others, while in some cases the fires are started with malicious intent. So great is the importance of protecting forests from fire, that this Department will make special effort for the enforcement of the law against all persons guilty of starting or causing the spread of forest fires in the reservations in violation of the above provisions.

6. The law of June 4, 1897, for forest reserve regulations, also provides that—

The jurisdiction, both civil and criminal, over persons within such reservations shall not be affected or changed by reason of the existence of such reservations, except so far as the punishment of offenses against the United States therein is concerned; the intent and meaning of this provision being that the State wherein any such reservation is situated shall not, by reason of the establishment thereof, lose its jurisdiction, nor the inhabitants thereof their rights and privileges as citizens, or be absolved from their duties as citizens of the State.

PUBLIC AND PRIVATE USES.

7. It is further provided, that—

Nothing herein shall be construed as prohibiting the egress or ingress of actual settlers residing within the boundaries of such reservations, or from crossing the same to and from their property or homes; and such wagon roads and other improvements may be constructed thereon as may be necessary to reach their homes and to utilize their property under such rules and regulations as may be prescribed by the Secretary of the Interior. Nor shall anything herein prohibit any person from entering upon such forest reservations for all proper and lawful purposes, including that of prospecting, locating, and developing the mineral resources thereof: Provided, That such persons comply with the rules and regulations covering such forest reservations.

The settlers residing within the exterior boundaries of such forest reservations, or in the vicinity thereof, may maintain schools and churches within such reservation, and for that purpose may occupy any part of the said forest reservation, not exceeding 2 acres for each schoolhouse and 1 acre for a church.

All waters on such reservations may be used for domestic, mining, milling, or irrigation purposes, under the laws of the State wherein such forest reservations are situated, or under the laws of the United States and the rules and regulations established thereunder.

8. The public, in entering, crossing, and occupying the reserves, for the purposes enumerated in the law, are subject to a strict compliance with the rules and regulations governing the reserves.

9. Private wagon roads and county roads may be constructed over the public lands in the reserves wherever they may be found necessary or useful, but no rights shall be acquired in said roads running over the public lands as against the United States. Before public timber, stone, or other material can be taken for the construction of such roads, permission must first be obtained from the Secretary of the Interior. The application for such privilege should describe the location and direction of the road, its length and width, the probable quantity of material required, the location of such material and its estimated value.