|

CRATER LAKE

Administrative History |

|

|

VOLUME I PART II: MANAGEMENT AND ADMINISTRATION OF CRATER LAKE NATIONAL PARK UNDER THE OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF THE INTERIOR: 1902-1916 |

CHAPTER EIGHT:

ADMINISTRATION OF CRATER LAKE NATIONAL PARK UNDER SUPERINTENDENT WILLIAM G. STEEL: 1913-1916

William G. Steel served as superintendent of Crater Lake National Park from July 1913 to November 20, 1916. During his 3-1/2 years as superintendent Steel continued to spearhead efforts for the development of the park that he had done much to bring into existence. His dreams for the park, however, were tempered by the lack of adequate congressional appropriations.

During his tenure as superintendent the park staff grew slowly. A second seasonal park ranger was hired to aid Momyer in 1913. Two years later Momyer became the first permanent park ranger at Crater Lake and a guard was added to the protection force. Thus, the embryonic ranger organization in 1915 consisted of Momyer, First Class Park Ranger; F.J. Murphy, Temporary Park Ranger; and M.L. Edwards, Guard. [1]

One of the first projects carried out by Steel was to establish an enlarged park headquarters at Anna Spring. The name of park headquarters was changed from Camp Arant to Anna Spring Camp. During the summer of 1913 he had a small cottage moved to the main road and had it remodeled for "a convenient office building." He observed:

Heretofore a small room in the superintendent's residence has been used for both living and business purposes, which of itself was unsuited for public use; besides, it was fully 200 feet from the road. Within this office I have installed an excellent vertical filing cabinet and have all park papers and correspondence systematically filed. The front room is used by the chief ranger, who registers visitors and issues licenses to the public, whereas the back room is used by the superintendent. This arrangement permits of the entire upstairs being utilized for storing supplies, as sleeping quarters for employees, or for emergency.

The new office, however, became inadequate for park needs by 1915. In that year Steel commented on the need for a new administration building:

The park office has entirely outgrown its usefulness, in that it is totally inadequate for the purpose. The park office proper and the post office are located in a little room 8 by 12 feet, into which at times 40 to 50 people try to crowd and transact business. When the mail arrives on busy days it is simply a physical impossibility to transact business expeditiously or at all satisfactorily either to the public or the employees.

A new modern building should be provided, as soon as possible, of sufficient capacity to meet all requirements for many years to come. The business is increasing rapidly and facilities for the systematic handling of it should keep pace therewith. Aside from convenient facilities for handling a greatly increased business, provision should be made for the public in the way of toilets, waiting rooms, and other comforts and conveniences.

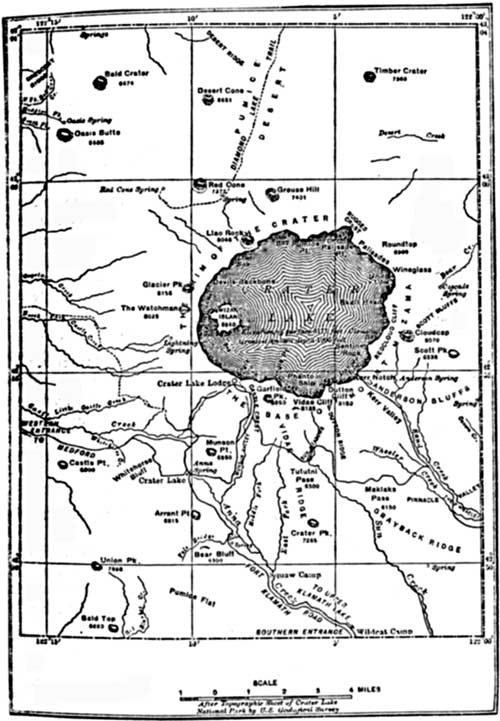

One of the principal continuing activities in the park during Steel's superintendency was that of road construction under the direction of the Corps of Engineers. By the end of his tenure as superintendent Steel was able to report:

About 47 miles of excellent dirt roads have been constructed in the park under the direction of the Secretary of War, which consist of 8 miles from the Klamath, or southern entrance, to park headquarters; 7 miles from the Medford, or western entrance, to the same point; 5 miles from park headquarters to the rim of the lake at Crater Lake Lodge; 6 miles from the Pinnacles, or eastern entrance, to the rim of the lake at Kerr Notch; and 22 miles from Cloud Cap, on the eastern side, to a point about 1-1/2 miles south of Llao Rock, to the west of the lake, thus leaving 12 miles to complete the circle of the lake, which latter it is hoped will be finished during the season of 1917, thus affording one of the most wildly beautiful automobile drives in the world. These roads have had ample time to settle and it is now proposed to pave them, which work should be completed in about three years.

Earlier in 1914 Steel had explained his views on paving the roads under construction:

I understand it is the intention of the War Department to commence surfacing as soon as climatic conditions will permit in the spring of 1915. This plan is questionable, for the reason that if this is done it will be impossible for many years to get anything better, whereas if surfacing is left for the present it will permit of an effort being made to secure from Congress money with which to construct paved roads.

The time has forever passed when macadam roads will satisfy the desires of a progressive community, and they are rapidly being changed for something very much better. Then why construct something that will be unsatisfactory from the very beginning? According to estimates of the War Department it will cost $20,000 per annum merely to sprinkle such roads. It is the part of wisdom to build roads of such a character as that this heavy burden will not have to be borne. I hope to make the Crater Lake National Park self-sustaining in a few years, but if this great burden is to be added that happy condition will be delayed indefinitely.

In addition to the road network Steel was proud of the Mount Scott Trail he had initiated in the park. In 1916 he noted that

a system of trails has been outlined that will appeal irresistibly to visitors who delight in wandering over the bluffs, through the forests, and into uncanny spots where goblins dance by night and shadows linger by day. Chief among these is one to be constructed to the summit of Mount Scott, on a grade that can subsequently be widened for automobile use. When this is done one can ride in comfort to a point nearly 3,000 feet above the waters of the lake and nearly 5,000 above the plains of eastern Oregon, over which the eye can wander, intoxicated with the glory of a view from the Columbia River region to the mountains of California.

Fishing prospects in the lake continued to be enhanced by planting both by the Crater Lake Company and park management. In 1914, for instance, the company placed 2,000 rainbow fry in the lake and Steel planted 20,000 steelheads. The following year Steel planted 15,000 black spotted fry in the lake. Steel recommended that no further planting be done until the matter of fish food had been settled. As there were "no enemies to fish already in the lake," their numbers had grown enormously to the point that the lake was "fairly teeming with them." However, nothing had ever been done to increase the food supply for the fish.

One of the first wildlife management issues that Steel confronted was that of deer being chased by loose dogs in the park. While there were many deer in the park they were rarely seen along park roads because, according to Steel, "dogs have been permitted to run at large and probably chase them, causing them to become shy." Thus, on September 13, 1913, the Department of the Interior, at the recommendation of Steel, issued the following instructions:

Visitors to the Crater Lake National Park are hereby notified that when dogs are taken through the park they must be prevented from chasing the animals and birds or annoying passers-by. To this end they must be carried in the wagons or led behind them while traveling and kept within the limits of the camp when halted. Any dog found at large in disregard of these instructions will be killed.

Game protection continued to be a problem for Steel as it had been for Arant. In 1913 Steel described the problems he was facing in protection of park wildlife:

But two temporary rangers are allowed during the season, one of whom is constantly employed in issuing licenses and registering visitors, so that one man must patrol the entire park. Then is it strange that there is always a report current that deer are slaughtered by poachers, who only need keep track of the ranger to carry on their nefarious practices with perfect impunity? However, hunting in the park is not general by any means, and is only carried on by an irresponsible class of semicriminals. Because of the protection afforded, deer in the park become very tame during the summer and when driven to the lower levels by the first heavy snow fall an easy prey to the despised deer skinners.

Accordingly, he, like Arant, proposed the creation of

game preserve, to embrace not only the park but all that portion of the forest reserve on the north to township 26 and on the west to range 1, Willamette meridian, then giving to it just such protection as is now afforded to other game preserves of a similar character.

In 1914 Steel proposed a second solution to the problem of game protection and overall law enforcement in the park. He observed:

If the department will allow five additional rangers, three of them will be needed for issuing automobile licenses and registering visitors at park entrances, one will be detailed for clerical work at headquarters, and three will be used to patrol the park. Of the latter one should be stationed at the Medford entrance to patrol north of the Medford Road and west of the lake, one at the Pinnacles entrance to patrol the eastern side of the park, and one at headquarters to patrol the southern portion, together with that portion of the rim in the vicinity of Crater Lake Lodge. By this arrangement fairly good patrol of the park can be maintained and deer hunters held in check. Besides this the danger of forest fires would be materially reduced and the work of park administration greatly improved.

Forest fires continued to be a critical problem for Superintendent Steel. In 1913 several small fires were started by careless campers. In one case in which live trees were destroyed, the offenders were apprehended and ejected from the park. The summers of 1914 and 1915 were unusually dry, thus leading to extraordinary precautions against forest fires. More than twenty fires broke out in the park in 1914, although all were extinguished before significant damage resulted. Thunderstorms and lightning ignited many of the fires in the park, the most significant occurring in 1916 when one storm resulted in four fires in the park and ten in the surrounding forests.

Road repair work during the spring continued to be a major component of Steel's duties as he prepared the park for the summer tourists. To repair the washed out roads he began a new practice of cutting out the road sides and dragging them rather than "cutting out the middle."

Steel also gave attention to trail maintenance. The trail to the lake was in need of major repairs virtually every spring. In 1913 rocks were removed from the trait so that burros kept by the Crater Lake Company could pass over it.

Steel began a program of "cleaning" the grounds and roadsides of the park of "dead and down timber." He did so because this debris afforded "dangerously inflammable material for spreading fire and destruction." In 1913 he stated:

All this [debris] should be cleaned up, together with such underbrush as interferes, but the cost would be prohibitive. However, a certain amount of this work can be done every year along the roads, and in the course of time a system of clear places can be established that will reduce the danger of fire to a minimum. I have in this manner cleared the road on both sides from headquarters toward the lake to a distance of about a mile and have carefully trimmed the trees, which not only adds a degree of safety but greatly beautifies the park.

Under an agreement with the War Department the first unit of a proposed sprinkling system for park roads was installed in September 1914. This involved construction of a water tank on a hill near the park headquarters that provided sufficient pressure for a gravity system and fire protection facilities for the headquarters area. At a cost of $1,200 the system was expanded during 1915. That year Steel described the system as containing

a main water line approximately 1,000 feet long, containing 332 feet of 3-inch and 670 feet of 2-inch pipe, with branch lines to the various buildings of approximately 500 feet of three-fourths-inch pipe. Modern plumbing has been installed in the superintendent's residence, consisting of bath, toilet, lavatory, kitchen sink, hot and cold water. A sewer system has been installed that can be extended as may be necessary. It is connected with a cesspool 10 feet deep, and as the soil is of an extremely light, porous nature, it will doubtless serve every purpose for many years. However, it is only a question of time when something better will have to be provided. Temporary sprinkling facilities have been provided, but it will soon be necessary to materially increase the supply of water by providing another tank. A public watering trough and a permanent water supply for the barn have been provided. A new hydraulic ram, fully equal to the present water supply, has been installed, but during the season of 1916 an additional tank should be placed above the present one, which latter should then be used for conserving the overflow for irrigating, and with such facilities there would be adequate protection against fire.

Steel also took steps to provide for garbage and tin can collection and disposal. These services were designed to improve the sanitary condition of the park campground areas.

In 1916 Steel proposed that efforts be made to provide the public with drinking water at the rim of he lake. He stated:

. . . This is of the first necessity and should be done as soon as possible. The Crater Lake Co. has established a water system for its own use and is constantly importuned for water by camping visitors, who do not understand conditions and take it for granted that it is a public supply, so resent any limitation. At times the supply is barely sufficient for hotel purposes, and it is necessary to refuse these requests, in consequence of which friction occurs and the Crater Lake Co. is abused without cause. The management has been extremely obliging in the premises and has suffered many times because of its desire to serve the public in this matter.

Permits for driving loose stock through the park continued to be issued during 1913-16. The peak year was 1915 when eight permits were granted to drive a total of 902 sheep, 393 cattle, and 9 horses through the park.

In addition to the aforementioned concessions granted to the Crater Lake Company and the Klamath Telephone & Telegraph company, two new concessionaires began operations in the park in 1913. The Kiser Photo Company of Portland and the Miller Photo Company of Klamath Falls were granted licenses for photographic privileges and the display and sale of views and post cards. The fees for these licenses were $10 per year. The license for the Kiser Photo Company was not renewed in 1915, thus giving the Miller Photo Company the sole right to photograph Crater Lake scenery and sell post cards.

A touch of scandal was associated with a concession permit granted to H.J. Boyd of Ashland for the period June 1-November 1, 1916. Under the terms of the permit Boyd was allowed "to bring people back through the Crater Lake National Park via the Lake" in his 1915 5-passenger Ford Touring Car "on his return from fishing trips" in Klamath and Lake counties. He was limited to a total of ten trips during the season. Later in December 1916 it was reported that Boyd had taken advantage of his permit since "his passengers were nearly all women, none of whom looked as though they were on a fishing trip. [2]

Increasing numbers of automobiles were driven to the park by vacationers during 1913-16. In 1913 permits were issued to 760 automobiles and 13 motorcycles at $1 each for a single round trip through the park. By 1915 the number of permits issued included: 2,231 round-trip automobile permits at $1 each; 13 season automobile permits at $5 each; and 30 round-trip motorcycle permits at $1 each. In 1916 2,649 automobiles entered the park, an all-time record to date. The growing number of automobiles in the park led the Department of the Interior to issue new automobile regulations for the park in 1916, a copy of which may be seen in Appendix A.

Park visitation continued to grow during 1913-16. In 1913, for instance, park visitation totaled 6,253 (June--43; July--1,144; August--3,002; September--1,637; October--418; November--9). That year the total number of guests entertained at the two permanent camps in the park was 2,240, a gain of more than sixty percent over the total for 1912.

Park visitation increased to 7,096 in 1914, the first year for which there are available published records providing statistical breakdowns both for monthly and state breakdowns. These statistics were:

Visitors to Crater Lake National Park

| February | 8 | August | 2,923 | |

| March | 6 | September | 1,167 | |

| May | 98 | |||

| June | 345 | |||

| July | 2,549 | Total | 7,096 |

Visitors by States

| Alabama | 2 | Montana | 3 | |

| Arizona | 7 | Nebraska | 10 | |

| British Columbia | 11 | Nevada | 15 | |

| California | 932 | New Mexico | 2 | |

| Canada | 1 | New York | 11 | |

| Colorado | 4 | North Carolina | 3 | |

| Connecticut | 6 | Ohio | 6 | |

| District of Columbia | 2 | Oklahoma | 1 | |

| Germany | 1 | Oregon | 5,781 | |

| Hawaii | 8 | Pennsylvania | 3 | |

| Idaho | 29 | Philippines | 2 | |

| Illinois | 15 | Tennesse | 3 | |

| Indiana | 1 | Texas | 6 | |

| Iowa | 8 | Utah | 4 | |

| Kansas | 13 | Washington | 164 | |

| Maryland | 1 | West Virginia | 1 | |

| Massachusetts | 7 | Wisconsin | 3 | |

| Michigan | 1 | |||

| Minnesota | 13 | |||

| Missouri | 16 | Total | 7,096 |

Visitation increased to 11,371 in 1915, stimulated in part by two world's fairs on the Pacific Coast. Of this total, more than 10,000 visitors were from the states of Oregon (8,869), California (1,147), and Washington (305). Three foreign countries were also represented: Canada (12), England (1), and Sweden (1). Every state in the Union was represented except for South Carolina, South Dakota, and Virginia.

In August 1915 William Jennings Bryan, who had resigned recently as Secretary of State, visited Crater Lake while on a western vacation. After spending the night in the recently completed lodge, he and his wife, accompanied by Superintendent Steel and several park rangers, walked down to the lake for a launch trip. The taxing climb back up to the rim led to Bryan's notorious proposal for construction of "a tunnel just above the lake level, through the rim to a connecting road." He proposed the tunnel so that visitors could reach the lake "without the laborious one thousand feet or more steep descent and climb over a slippery and dangerous trail" which could "only be made a few months of the year and is almost impossible for old people." [3]

Steel took up the campaign for a tunnel to the lake. In 1916 he formally requested $1,000 to conduct surveys for a tunnel. His justification for such an expenditure read:

From Crater Lake Lodge to the lake is a drop of nearly 1,000 feet, and to reach the lake a trail of 2,300 feet is provided. Owing to the rugged nature of the rim, this trail is necessarily steep and hard to climb, and many visitors are unable to go over it, so that they are denied the privilege of fishing or boating on the lake. This condition of affairs is a disappointment to many visitors and some sort of provision should be made to overcome it. A lift or other installation within the rim is wholly impracticable, for the reason that every spring enormous slides of snow and rocks would sweep any sort of framework into the lake. Under such conditions I would suggest the construction of a tunnel from a convenient point on the road several hundred feet below the rim, to the surface of the water. . . .

Despite heavy and late snows in 1916, park visitation increased to an all-time high to date of 12,265. This figure was reached despite the fact that at the close of July travel was only fifty percent of the previous year.

One of the improvements to park facilities and services carried out by Steel was the installation of a new telephone system. In 1915 he reported on his efforts:

Telephone facilities of the park have never been satisfactory, so during the past season private lines in the park were purchased and necessary lines constructed. Direct connection with Klamath Falls by way of Fort Klamath has been maintained for a number of years, but never before has there been direct connection with Medford and the Rogue River Valley. I was unable to build beyond the park line, which would leave a distance of 23 miles to connect at Prospect, and as the prospective business would not justify the expense of construction by a commercial organization, I was forced to provide ways and means, which I did by securing sufficient voluntary contributions, with which a good line was built and is now in excellent working order. A switchboard has been provided for the park office, and all lines are controlled therein.

Throughout his superintendency Steel continued to make recommendations for park improvements, many of which were not implemented because of inadequate park appropriations. Among these proposals was an electric light and power plant near the park headquarters to provide light and operate machinery in a woodworking and blacksmith shop that he wished to construct. He recommended that the falls of Anna Creek be used to operate the light and power plant. The expense of carrying electric power to the rim of the lake would be inexpensive, since the park would raise revenue by supplying light and power to the concessionaires.

The question of patented lands in the park continued to bother Steel. In 1913 and 1914 he urged that such titles to park lands be terminated to forestall private development:

There are approximately 1,200 acres of private land within the park, probably all of which is held for speculation. It is covered with excellent timber, and it is only a question of a little time when some speculator or mill man will gather it up, when the next move will be to cut off all the trees and leave it as "logged-off land" is usually left, covered with kindlings but denuded of trees.

Early action should be taken to extinguish these titles, either by the ordinary method of condemnation and purchase or by offering therefor other lands located outside of the park.

Steel recommended that a building be constructed to provide dining, sleeping, and living quarters for seasonal park workers. Since the park was far removed from population centers it was difficult at best to attract summer labor. In view of the fact that the Klamath region was stock country and haying operations reached their peak in July and August, laborers were in demand at good wages during the summer. The lack of adequate housing and sanitary facilities made it even more difficult to attract park labor.

Steel became enamored with the idea of government ownership of all concessions and private development in the park. His goal became that of making Crater Lake a self-sustaining entity. In 1914, for instance, he stated:

The frequent changes of administration in this Government, together with the unsatisfactory condition in which the national park service is left by Congress, are so pronounced that capitalists are unwilling to advance funds on park concessions in amounts adequate to their needs, in consequence of which rapid development is seriously impaired, and the impression is gaining ground among men of large means that such investments are extra hazardous. Under such conditions it seems to me imperative that the General government acquire possession of all hotels and other permanent improvements of a private nature within the parks, and that they then be leased to desirable parties for a reasonable consideration. This would be an important step toward making the parks self-sustaining, which they should be. With the road system completed, this revenue, together with that received from automobiles, would make the Crater Lake Park self-sustaining from the start, providing a comprehensive plan of management were developed to meet new conditions. Construction of private improvements at Crater Lake is yet in is infancy, for which reason I would recommend that the experiment be tried here, where the initial outlay would be comparatively light.

In 1914 and 1915 Steel renewed earlier recommendations to expand the park boundaries northward and westward and enlarge the park to include Diamond Lake, Mount Thielsen, and Mount Bailey. After considerable study of the issue, he observed in 1914:

Boundaries of the Crater Lake National Park were not originally located wisely, for the reason that but little was then known of the necessities of the case, or of physical conditions. Experience has shown that they should be changed to meet new and permanent conditions. . . .

In support of the foregoing, will say there are no settlers within the new boundaries. On the west there is a narrow strip of Klamath County that should be eliminated and the park made to conform with the county line.

On the east there is also a narrow strip between the park and the Klamath Indian Reservation that should be eliminated and the park boundary made to conform with the Indian reservation.

On the north is located an extremely interesting region that is wholly within the Crater National Forest and should be included in the Crater Lake National Park in time to extend to it the road system now under construction. It is neither valuable for agriculture nor mining, and there is no public reason why this extension should not be made. On the other hand, I believe it will meet with approval of a vast majority of the people of the State. Within the proposed extension is located Diamond Lake, one of the most beautiful and attractive in the mountain region, and Mount Thielsen, a sharp peak standing over 9,000 feet above sea level and commonly known as the Lightning Rod of the Cascades, because of the brilliant displays of lightning about its pinnacle in stormy weather.

After consulting with the supervisors of the national forests surrounding Crater Lake National Park, Steel and the forestry officials agreed to support jointly a revision and extension of the park boundaries in 1915. The revised park boundaries, which soon encountered opposition, read:

Commencing at the western extremity of the south boundary of the Crater Lake National Park, thence west approximately three-quarters of a mile to the boundary between Klamath and Jackson Counties, thence north along said county line to a point on the boundary between Douglas and Jackson Counties, thence east to a point due north of the present western line of the park, thence north to a point 2 miles north of the sixth standard parallel, thence east to a point on the east boundary of the Umpqua National Forest, thence southerly along the said eastern boundary of the Umpqua National Forest to the present north line of the Crater Lake National Park. [4]

In view of the foregoing examination of park management issues and development projects in Crater Lake National Park during 1913-16, the question arises as to the type, details, and quality of experience that a park visitor had during those years. [5] During these years the tourist season generally extended from June 15 to September 30.

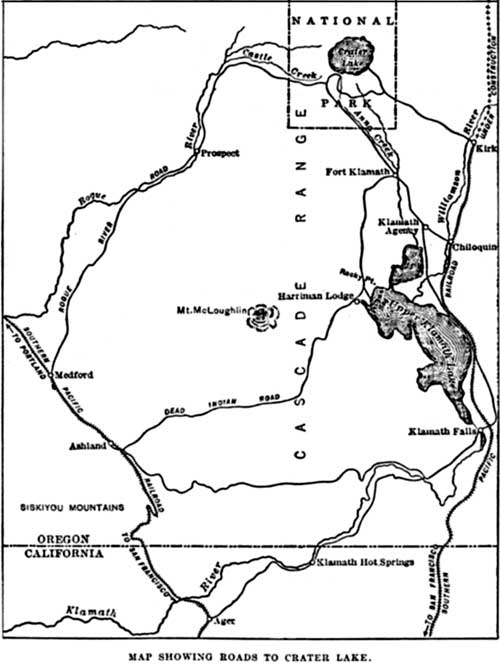

In a general park information circular for 1913 the visitor accommodations and means by which the park could be reached were described. According to the brochure the park was accessible from

Klamath Falls, Chiloquin, Medford, and Ashland on the Southern Pacific Railroad. According to present advices, Klamath Falls is the only point from which regular transportation service will be available. Tourists will proceed by bus from Klamath Falls to Upper Klamath Lake, thence by launch to Harriman Lodge, thence by automobile to Crater Lake. Between Klamath Falls and Harriman Lodge the service will be rendered by the Klamath Development Co. (address, Klamath Falls, Oreg.); between Harriman Lodge and Crater Lake the service will be performed by the Crater Lake Co. (address, Crater Lake, Oreg.).

Visitor accommodations provided by the Crater Lake Company included:

At Crater Lake Lodge on the rim of the lake guests are furnished with comfortable beds in floored tents. Meals are served in a frame building pending the completion of the lodge.

At Camp Arant, 5 miles below the rim of Crater Lake, the Crater Lake Co. maintains a camp for the accommodation of guests, a general store for the sale of provisions and campers' supplies, and a livery barn.

Free camping privileges in designated areas were open to the public subject to park regulations. [6]

Arrangements were made to improve transportation to the park during the 1913-16 period. Prior to these years the Crater Lake Company had maintained a line of automobile stages from Medford on the main line of the Southern Pacific, a distance of 85 miles from the park. In 1914 similar service was begun from Chiloquin on the northerly extension of the Southern Pacific (known as the Crater Lake or Natron cut-off) from Klamath Falls. That same year was the first time in the history of the park that one could purchase a ticket from Portland to California towns, or vice versa, and travel via Crater Lake at an additional expense of only $13 for automobile fare between Medford or Chiloquin.

Authorized Rates, Crater Lake Company, 1913

| Meals at Camp Arant or Crater Lake Lodge. | |

| Single meals | $1.00 |

| 2 or more meals, each | .75 |

| Beds, per day, at Camp Arant or Crater Lake Lodge, per person | 1.00 |

| Board and lodging, per day, at Camp Arant or Crater Lake Lodge, per person | 3.25 |

| Board and lodging, per week, at Camp Arant or Crater Lake Lodge, per person | 17.50 |

| Children under 12 years, half rates | |

| Unfurnished tents for campers, per day | 1.00 |

| Furnished tents for campers (no cooking utensils), per day per person | 1.00 |

| Automobile transportation within the park, per mile | .10 |

| Saddle horses, pack animals, and burros, per hour | .50 |

| Saddle horses, pack animals, and burros, per day | 5.00 |

| Launch trip, Wizard Island and return, per person | 1.00 |

| Launch trip around Wizard Island and Phantom Ship and return (about 15 miles), per person | 2.50 |

| Launch charter, per hour | 5.00 |

| Launch charter, per day | 20.00 |

| Rowboats, per hour | .50 |

| Rowboats, per day | 2.50 |

| Rowboats with detachable motor, per hour | 2.50 |

| Rowboats with detachable motor, per day | 10.00 |

| Provisions, tourist supplies, gasoline, motor, hay, and grain at reasonable rates | |

The details of railroad and concession-operated automobile transportation to the park in 1914 was described in a general information circular. It stated:

This park may be reached from Klamath Falls, Chiloquin, Medford, and Ashland on the Southern Pacific Railroad. There is train service between Klamath Falls and Chiloquin only on Monday, Wednesday, and Saturday. The Southern Pacific Co. will sell excursion tickets to Crater Lake from July 1 to September 25, inclusive. . . .

The Crater Lake Co. operates a triweekly automobile service between Medford and Crater Lake and between Chiloquin and Crater Lake as follows:

Autos leave the Hotels Medford and Nash, Medford, at 9 a.m. Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, stop for lunch at Prospect, and reach Crater Lake in time for 6 o'clock dinner. Returning, leave Crater Lake at 9 a.m. Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday, reaching Medford in time to connect with the outgoing evening trains.

Autos leave Crater Lake for Chiloquin at 9 a.m. Monday, Wednesday, and Saturday, connecting with the local Southern Pacific train from Klamath Falls. Returning, leave Chiloquin at 1 p.m. the same day and reach Crater Lake in time for 6 o'clock dinner.

Rates for the automobile service were:

| Medford to Crater Lake and return. | $18.00 | |

| One way (either direction) | $10.00 | |

| Chiloquin to Crater Lake and return | 9.00 | |

| One way (either direction) | 5.00 | |

| Medford to Crater Lake, thence to Chiloquin, or vice versa | 13.50 | [7] |

The account of a visitor to Crater Lake via private automobile during the summer of 1914 provides insight relative to park visitors' experiences during this period. The account, which was published in the December 1914 issue of the Ladd & Bush Quarterly, read:

In the summer, traveling in an automobile at a comfortable speed, the trip can be made from Salem to the lake in three days. . . .

The start from Medford should be made in time to reach Prospect for luncheon. Prospect Hotel meals will give satisfaction to the hungry traveler, and its kitchen, presided over by Mrs. Grieves, the mistress of the hotel, although in the mountains, is a model for convenience and cleanliness.

The first thirty miles the road is fine and one can "burn 'em up" if he is so inclined, but the remaining fifty miles cause a wish that an earlier start had been made, and if Rim Camp can be reached before dark it will be luck. Theoretically Mr. McMahon and the Supreme Court were probably correct, building a Crater Lake road is not a proper subject to collect taxes for from the whole state, but, after one has spent an afternoon bumping along that road, he will wish we were not such strict constructionists. At Rim camp the room will be in a tent, not half bad for a change. The new hotel is in process of construction, but at the rate it has progressed in the past, and considering that the snow got so deep and heavy last winter that it caved in the roof, the prospects for its being open in another year are not encouraging. . . . Many view the scenery from the rim and tell of its wonders, but they have seen little of what is there. By far the best view is from the lake and a whole day can be spent on it before it can be half appreciated. . . . At present the crest generally is passable for a pedestrian, who can follow it almost continuously around the lake, although it is a tedious and difficult trip, too much so to be undertaken by the usual visitor.

Rim Camp trail is down a depression carved in the rim by the sliding of the avalanches of ages. The trail winds back and forth, extending the distance to travel, but by so doing relieving the grade to some degree. Going down is the most difficult and dangerous, as the descent is steep and there is a risk of slipping. Most people fear the trip up, but by climbing leisurely it can be made with no risk and a limited amount of exertion. On reaching the water edge the blue of the water first absorbs attention; artists have in no way exaggerated it. The whole surface of the lake is of wonderful blues, shading from sky blue to deep indigo. One finds oneself ingeniously dipping up the water to see if it is really blue; it proves to be nothing more than plain water. The most prominent feature is Wizard Island, nearly two miles out in the lake. . . . As the boat ride progresses, the beauties of the lake, the continuous blue of the water, the ever-changing rim, bring before one new wonders. At several points along the edge cliffs 100 feet under the water can be seen, turning the blue water to pale green. The lake rim is composed of stratas of many colors, grays, browns, terra-cottas, creams, at places intense red beside various shades of greens. . . .

When the shades of night come on a fog quickly covers the lake and the lights become so deceptive that it is no longer possible to distinguish one portion of the rim from another. To prevent a boatman from becoming lost and being compelled to stay out all night, all are required to return to the landing by 5:30 P.M. From certain positions in the park the observer can see the base of the engulfed mountain rising about a thousand feet above the general crest of the range on which it stands, convincing more and more that there is probably truth in the supposition that above the lake once towered a lofty volcano.

Every Oregonian who can should visit Crater Lake. Its grandeur will well pay for the difficulties encountered in making the trip. But go while it is in its natural wildness, before railroads and other modern conveniences commercialize it and do not fail to go upon the water. [8]

On June 28, 1915, Crater Lake Lodge opened to the public. The building of cut-stone and frame construction contained 64 sleeping rooms and was described as having ample bathing and fire protection facilities. The lodge quickly became the focal point of visitor accommodations in the park. A branch of the general merchandise store at Camp Arant was located in the lodge building. Tents were also available at the lodge as sleeping quarters, meals being taken at the lodge. Anna Spring Camp continued to provide less expensive accommodations in its "well-floored tents." (See below for hotel and camp charges and maps relating to the park in 1915.) [9]

In addition to the railroad and concessioner-operated transportation arrangements for reaching the park, improvements continued to be made to roads leading to Crater Lake from the Klamath region and the Rogue River Valley during 1913-16. In the latter year the opening of the Pinnacles entrance on the eastern boundary facilitated park visitation from central and eastern Oregon.

Hotel and Camp Charges, Crater Lake Co., 1915

| CRATER LAKE LODGE | |

| Board and Lodging, each person, per day (lodging in tents) |

$3.00 |

| Board and lodging, each person, per week (lodging in tents) |

17.50 |

| Board and lodging, each person, per day (hotel) | 3.50 |

| Board and lodging, each person, per week (hotel) | 20.00 |

| Board and lodging, each person, per day, in rooms with hot and cold water | 4.00 |

| Board and lodging, each person, per week, in rooms with hot and cold water | 22.50 |

| Baths (extra) | .50 |

| Fires in rooms (extra) | .25 |

| Single meals | 1.00 |

| ANNA SPRING TENT CAMP | |

| Board and lodging, each person, per day | 2.50 |

| Board and lodging, each person, per week Meals: Breakfast or lunch, 50 cents; dinner, 75 cents |

15.00 |

| Fires in tents (extra) Children under 12 years, half rates at lodge or camp. |

.25 |

| TRANSPORTATION | |

| Automobile fare between Anna Spring Camp and Crater Lake Lodge: One way Round trip |

.50 1.00 |

| Automobile transportation, 10 cents per mile within the park | |

| Saddle horses, pack animals, and burros (when furnished), per hour | .50 |

| Saddle horses, pack animals, and burros (when furnished), per day | 5.00 |

| Launch trip, Wizard Island and return, per person | 1.00 |

| Launch trip around Wizard Island and Phantom Ship and return (about 15 miles), per person | 2.50 |

| Launch trip around the lake | 3.50 |

| Rowboats, per hour | .50 |

| Rowboats, per day | 2.50 |

| Rowboat, with boat puller, per hour | 1.00 |

| Rowboat, with detachable motor, per hour | 1.00 |

| Rowboat, with detachable motor, per day | 5.00 |

| Provisions, tourists' supplies, gasoline, motor oil, hay and grain at reasonable rates at the general store at Anna Spring Camp and branch store at Crater Lake Lodge. | |

APPENDIX A:

Automobile Regulations of March 1, 1916

Pursuant to authority conferred by the act of May 22, 1902 (32 Stats., 202), setting aside certain lands in the State of Oregon as a public park, the following regulations governing the admission of automobiles into the Crater Lake National Park are hereby established and made public:

1. Entrances--Automobiles may enter and leave the park by either of the three entrances.

2. Automobiles--The park is open to automobiles operated for pleasure, but not to those carrying passengers who are paying, either directly or indirectly, for the use of machines (excepting, however, automobiles used by concessionaires under permits from the department). Careful driving is demanded of all persons using the roads. The Government is in no way responsible for any kind of accident.

3. Fees--Entrance fees are payable in cash only, and will be as follows:

| Single trip permit | $2 |

| Season permit | $3 |

4. Automobile permits--Automobile permits must be secured at the checking station where the automobile enters the park. This permit must be conveniently kept so that it can be exhibited to park rangers on demand. Each trip permit must be exhibited to automobile checker at point of exit, who will stamp across the back of the permit: "Void after _______ (hour and date)" and return to owner or driver. The automobile may then reenter the park by the same or any other road (or entrance) within 12 hours from time of leaving park.

Automobile permits will show (a) name of station issuing permit, (b) name of owner or driver, (c) State and license number of automobile.

5. Muffler cut-outs--Muffler cut-outs must be closed while approaching or passing riding horses, horse-drawn vehicles, hotels, camps, or checking stations.

6. Distance apart--Gears and brakes--Automobiles while in motion must not be less than 50 yards apart, except for purpose of passing, which is permissible only on comparatively level or slight grades. All automobiles, except while shifting gears, must retain their gears constantly enmeshed. Persons desiring to enter the park in an automobile will be required to satisfy the guard issuing the automobile permit that the machine in general (and particularly the brakes and tires) is in first-class working order and capable of making the trip, and that there is sufficient gasoline in the tank to reach the next place where it may be obtained. The automobile must carry two extra tires. All drivers will be required effectually to block and skid the rear wheels with either foot or hand brake, or such other brakes as may be a part of the equipment of the automobile.

7. Speeds--Speed is limited to 10 miles per hour, except on straight stretches, when, if no team is nearer than 200 yards, it may be increased not to exceed 20 miles per hour.

8. Horns--The horn will be sounded on approaching curves, or stretches of road concealed for any considerable distance by slopes, overhanging trees, or other obstacles; and before meeting or passing other machines, riding or driving animals, or pedestrians.

9. Teams--When teams, saddle horses, or pack trains approach, automobiles will take the outer edge of the roadway, regardless of the direction in which they are going, taking care that sufficient room is left on the inside for the passage of vehicles and animals. Teams have the right of way, and automobiles will be backed or otherwise handled as may be necessary so as to enable teams to pass with safety. In no case must automobiles pass animals on the road at a speed greater than 8 miles per hour.

10. Accidents--When, due to breakdown or accidents of any other nature, automobiles are unable to keep going, they must be immediately parked off the road, or, where this is impossible, on the outer edge of the road.

11. Stop-overs--Automobiles stopping over at points other than the hotels or permanent camps, must be parked off the road, or where this is impossible, on the outer edge of the road.

12. Reduced engine power--Gasoline, etc.--Due to the high altitude of the park roads, ranging between 4,000 and 7,000 feet, the power of all automobiles is much reduced, so that about 50 per cent more gasoline will be required than for the same distance at lower altitudes. Likewise one lower gear will generally have to be used on grades than would have to be used in other places. A further effect that must be watched is the heating of the engine on long grades, which may become serious unless care is used. Gasoline can be purchased at regular supply stations as per posted notices .

13. Penalties--Violation of any of the foregoing regulations for government of the park will cause revocation of automobile permit, will subject the owner of the automobile to immediate ejectment from the park, and be cause for refusal to issue new automobile permit to the owner without prior sanction in writing from the Secretary of the Interior.

14. Damages--The owners of automobiles will be responsible for any damages caused by accident or otherwise.

15. All persons passing through the park with automobiles are required to stop at the supervisor's headquarters or the rangers headquarters and register their names.

16. Motorcycles--These regulations are also applicable to motorcycles, which may use the roads on payment of a fee of $1 for each machine per annum; permits issued therefor shall expire on December 31 of the year of issue.

U.S. Department of the Interior, The Crater Lake National Park, Season of 1916 (Washington, 1916), pp. 17-19.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

crla/adhi/chap8.htm

Last Updated: 13-Aug-2010