|

CRATER LAKE

Administrative History |

|

|

VOLUME I PART III: MANAGEMENT AND ADMINISTRATION OF CRATER LAKE NATIONAL PARK UNDER THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE: 1916-PRESENT |

CHAPTER NINE:

LEGISLATION RELATING TO CRATER LAKE NATIONAL PARK: 1916-PRESENT

The purpose of this chapter is the examination of legislation relating to Crater Lake National Park from 1916 to 1986. Emphasis is placed on the provisions of the various legislative acts and their impact on park management, operations, and expansion. Separate sections of this chapter are devoted to analyses of park wilderness designation proposals, acquisition of major park inholdings, and various unsuccessful efforts to expand the park boundaries.

A. LEGISLATIVE ACTS

1. An Act Providing for Acceptance by Federal Government of Exclusive Jurisdiction over Park Lands and Establishment of Resident U.S. Commissioner Position (39 Stat. 521--August 21, 1916)

On August 21, 1916, four days before enactment of the act establishing the National Park Service, Congress approved legislation providing for acceptance by the federal government of the State of Oregon's cession of exclusive jurisdiction over the lands embraced in Crater Lake National Park. The legislation further provided for appointment of a U.S. Commissioner to reside in the park with authority to handle violations of law [misdemeanors] and rules and regulations promulgated by the Secretary of the Interior.

The Oregon state legislature approved an act on January 25, 1915, ceding to the United States exclusive jurisdiction over all lands within Crater Lake National Park. [1] The act reserved certain rights for the state, among these being service of "civil or criminal process" in "any suits or prosecutions for, or on account of, rights acquired, obligations incurred, or crimes committed in said State, but outside of said park." The state also reserved "the right to tax persons and corporations, their franchises and property on lands included in said park." Exclusive jurisdiction would not be vested in the federal government until after it had notified the state that it was assuming "police and military jurisdiction over said park."

Section 3 of the act states that confusion existed concerning the jurisdiction of the federal and state courts in the park. Hence passage of the act was "declared to be immediately necessary for the immediate protection of the peace, health, and safety of the State." An emergency was "declared to exist, and this Act shall go into immediate force and effect from and after its passage and approval by the Governor."

For more than a year Congress took no formal action to accept the cession of exclusive jurisdiction over Crater Lake National Park. Finally on April 20, 1916, Congressman Nicholas J. Sinnott of Oregon introduced legislation (H.R. 14868) in the House to accept the cession from the State of Oregon. Two days later Senator George E. Chamberlain of Oregon submitted a similar bill (S. 5704) in the Senate. [2]

The Sinnott bill was referred to the House Committee on Public Lands. In response to a request from committee chairman Scott Ferris, Secretary of the Interior Franklin K. Lane submitted a letter on May 3 endorsing the legislation:

The provisions of this bill are identical, except for the necessary changes to make it applicable to Crater Lake National Park, instead of Glacier National Park, with the provisions of the act of Congress approved August 22, 1914 (38 Stat., 699), accepting similar jurisdiction ceded by the State of Montana over the Glacier National Park. It also follows generally the provisions of S. 3928, to accept similar jurisdiction over the Mount Rainier National Park, Wash., which passed the Senate on March 9, 1916, and which is now pending in the House of Representatives.

It is very desirable for administrative reasons that the cession of jurisdiction by the State of Oregon over the lands within Crater Lake National Park should be accepted, and I recommend that the bill be enacted into law at the earliest practicable date. [3]

The Committee on Public Lands reported the bill with several minor amendments on June 22, and on July 1 the House passed the legislation. The bill was sent to the Senate on July 3, and nine days later the Senate Committee on Public Lands reported favorably on the bill. [4] After passing the Senate on August 5, the legislation (39 Stat. 521) was signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson on August 21. [5]

The law, as was customary with such acceptance bills, included detailed regulations for the park's administration. The park was declared part of the United States judicial district for Oregon. The United States District Court for Oregon, which had jurisdiction over all offenses committed in the park, was to appoint a commissioner who would live in the park for the purpose of hearing and acting "upon all complaints made of any violations of law [misdemeanors] or of the rules and regulations made by the Secretary of the Interior for the government of the park." The commissioner would receive a salary of $1,500 per year.

2. An Act Making Appropriations for Sundry Civil Expenses of the Government for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1918, and for Other Purposes (40 Stat. 152--June 12, 1917)

The general appropriations act for fiscal year 1918 contained a section (U.S.C., title 16, sec. 135) pertaining to the acquisition of land inholdings at Crater Lake National Park. By its provisions the Secretary of the Interior was authorized to accept patented lands or rights of way over patented lands in the park that might be donated for park purposes.

While this specific authorization pertaining to Crater Lake was repealed by 46 Stat. 1028 in 1931, its general provisions were covered by 41 Stat. 917, a government appropriations bill approved by Congress on June 5, 1920. In "An Act Making Appropriations for Sundry Civil Expenses of the Government for the Fiscal Year ending June 30, 1921, and for other purposes," Congress granted:

The Secretary of the Interior in his administration of the National Park Service is authorized, in his discretion, to accept patented lands, rights of way over patented lands or other lands, buildings, or other property within the various national parks and national monuments, and moneys which may be for the purposes of the national park and monument system. [6]

3. An Act Accepting Certain Tracts of Land in the City of Medford, Jackson County, Oregon (43 Stat. 606--June 7, 1924)

From the inception of the park its superintendents had established their winter quarters and offices outside the park. This was due to the annual heavy snowfalls which made the park largely inaccessible from mid-autumn to late spring. By 1924 the open season for the park was from July 1 to September 30, during which time the superintendent established summer headquarters in the park. During the remainder of the year the park office was located in one room of the Federal Building in Medford. The superintendent rented living quarters in the town, and all park motor vehicles and road-building machinery was stored in the open on private land, the use of which had been granted by the public-spirited owners. [7]

During 1923 negotiations between Park Service officials and Medford town leaders resulted in the offer of three lots in fee simple as sites for buildings to be used for park administrative purposes. After the National Park Service indicated interest the Medford City Council passed an ordinance tendering to the United States the three lots on a tax and assessment free basis. It was contemplated that a warehouse and a combined residence and office for the park superintendent would be built on the lots. [8]

To enable the federal government to accept these lots Senator Irvine L. Lenroot of Wisconsin, who was chairman of the Senate Committee on Public Lands and Surveys, introduced legislation (S. 1987) on January 15, 1924. The bill read:

That the Secretary of the Interior be, and he is hereby, authorized to accept certain tracts of land in the city of Medford, Jackson County, Oregon, described as lots numbered 15 and 16, block 9, amended plat to Queen Ann Addition to the city of Medford: and lot 3, block 2, central subdivision to the city of Medford, which have been tendered to the United States of America in fee simple by the city of Medford, Oregon, as sites for buildings to be used in connection with the administration of Crater Lake National Park, Oregon. [9]

In response to a request by Lenroot, Secretary of the Interior Hubert Work submitted the department's recommendation for passage on January 31, 1924. The report read in part:

A warehouse at this location will afford an opportunity to put under cover and distribute from a central point supplies and equipment which may be purchased to better advantage during the winter and also to condition motor and other equipment so that the working forces of the park may be able to function immediately upon the opening date without having to carry on repair work at the same time.

In other national parks the superintendents are furnished and are able to spend the entire year within the park area. The superintendent of Crater Lake National Park, however, who receives a salary less than that of any other superintendent of a major park of the West, is obliged to provide a residence for his occupation during the closed season of the park. Experience has shown that it is difficult to find a suitable residence which may be leased at a reasonable cost for part of the year only. [10]

The bill encountered little opposition in Congress. It was reported favorably without amendment by the Senate Committee on Public Lands and Surveys on May 12, 1924, and passed the Senate ten days later. On May 24 the bill was referred to the House Committee on Public Lands, which reported it favorably without amendment on June 5. [11] The bill was approved by the House on June 7 and signed into law (43 Stat. 606) by President Calvin Coolidge that same day. [12]

After the enactment of the law proceedings were initiated for the formal conveyance of the two lots to the federal government. Accordingly, the two lots, comprising 0.13 and 0.28 acres respectively, were acquired and added to the park holdings on September 1, 1924. [13]

4. An Act to Add Certain Land to the Crater Lake National Park in the State of Oregon, and for Other Purposes (47 Stat. 155--May 14, 1932)

The long-sought effort to provide a more attractive southern entrance to the park and secure a more available water supply for park utilization was achieved by legislation in June 1932. On March 1 of that year Representative Robert R. Butler of Oregon introduced a bill (H.R. 9970) providing for the transfer of land from Crater National Forest to the park for such purposes. As introduced the bill provided:

That all of unsurveyed sections 2 and 11, north half and north half south south half section 14, and those parts of unsurveyed sections 1, 12, and 13, lying west of Anna Creek, in township 32 south, range 6 east, Willamette meridian in the State of Oregon be, and the same are hereby, excluded from the Crater National Forest and made a part of the Crater Lake National Park subject to all laws and regulations applicable to and governing said park. [14]

After the bill was referred to the House Committee on Public Lands its chairman, John M. Evans of Montana, requested the views of the Interior and Agriculture departments on the proposed legislation. On March 18 Secretary of the Interior Ray L. Wilbur submitted a memorandum in support of the bill that had been prepared by National Park Service Director Horace M. Albright three days before. In his memorandum Albright stated:

The extension proposed to be authorized by this legislation is the so-called Annie Creek extension of approximately 973 acres, to the south of Crater Lake National Park as recommended by the Coordinating Commission on National Parks and Forests.

The purposes of this extension are to secure for the Crater Lake National Park a more attractive entrance amid fine yellow pine forests and to secure a more available water supply for park purposes. This is of great administrative importance.

Because of unfavorable natural conditions and lack of available water supply at the south entrance to Crater Lake National Park, the idea of extending the park boundary some 3 miles farther south to include Annie Creek and the highway has been under consideration for the past five or six years. Such extension would provide a far more imposing park entrance and at the same time enable the development of a gravity water supply for ranger uses at the entrance.

The area was inspected by the Coordinating Commission on National Parks and Forests in 1926 and full agreement was reached on this proposed extension, which was also concurred in by the Forest Service. . . .

Albright went on to report that "an entirely new description of the area proposed to be added to the park" should be given in the bill. Hence he recommended new boundaries for the addition to the park:

That all of that certain tract described as follows: Beginning on the south boundary line of Crater Lake National Park at Four Mile Post No. 112; thence west along the south boundary line of said park 4.26 chains which is the northwest corner of this tract; thence south 114.42 chains; thence south 40°59' east, 84.39 chains; thence east 15.13 chains to highway stake No. 130; thence north 89°30' east, 18.06 chains; thence north 20.83 chains; thence north 19°40' west 126.04 chains; thence north 27°52' west 43.50 chains to the south boundary of Crater Lake National Park; thence west 24 chains, following the south boundary of said park to the place of beginning, in.

On March 16 Secretary of Agriculture Arthur M. Hyde submitted a report that gave less than enthusiastic endorsement to the bill, provided that Albright's revised boundary description was incorporated into its text. Hyde observed:

. . . It is understood informally from the National Park Service, that the bill incorrectly describes the lands which it is desired shall be affected by it and that a new description will be proposed; that this new description covers an area of approximately 973 acres extending along both sides of the Fort Klamath road for a distance slightly in excess of 2 miles; that the purpose of this addition is to insure a more attractive entrance to the Crater Lake National Park by giving especial protection to the timber along the highway.

This department feels that as a general rule such piecemeal adjustments of coterminus boundaries between national parks and national forests are less desirable and effective than comprehensive and permanent adjustments based upon careful studies of all factors involved which will include within the park all areas predominantly of park value and exclude from the park all areas predominantly of industrial value. It also dissents to the idea that the inclusion within national parks of the roads giving access thereto is essential to the maintenance of the scenic attractiveness of such roads, since this department in the administration of the national forests also adheres to a policy of conserving the scenic values of the lands abutting on the highways. In this particular instance, however, representatives of the Forest Service have agreed that the addition of a certain area to the park would not seriously conflict with the use and management of the surrounding national forest lands, and if the bill is amended to correctly describe that area, this department will offer no objections to its enactment.

After some deliberation the House Committee on Public Lands reported favorably on the bill I on March 24 with the recommendation that Albright's boundary revisions be inserted. [15] As amended the bill encountered little opposition in Congress. It passed the House on April 18, was referred to the Senate Committee on Public Lands and Surveys on April 19, and received a favorable report without amendments on April 26. [16]

After passage by the Senate on May 9 the bill was signed into law (47 Stat. 155) by President Herbert C. Hoover on May 14, 1932. Thus, 973 acres were added to the park, the addition becoming popularly referred to as the park's "southern panhandle."

The boundary change, which added some 973 acres to the park, had ramifications for the Park Service in terms of road maintenance. In response to inquiries from the Oregon State Highway Commission, Superintendent Elbert C. Solinsky stated on July 14, 1932:

It is true that our park boundary has been extended to include approximately 973 acres along the southern boundary. This addition includes a section of the state highway between Fort Klamath and the old park boundary. I believe approximately three miles of this highway have been added to the park and are now a part of the park highway system and subject to maintenance from Park Service funds. Unfortunately this year no allotments have been provided for the maintenance of this section. In fact practically no funds are available for road maintenance of our park roads. For that reason we will not undertake any maintenance work on the new section added by this boundary change this year. [17]

Some years later Superintendent Earnest P. Leavitt observed that considerable friction had developed between the Park Service and the Forest Service during negotiations for this addition to the park. Among other observations, he stated that:

. . . originally it was contemplated that the addition would be along section lines and would be a sizeable area. Before the addition was worked out, however, the Forest Service officials in charge became provoked at the National Park Service and determined that they would agree to only the very smallest area possible that was necessary to preserve this stand of ponderosa pine. The result is that we have a very narrow and irregular tongue of land extending south from the park boundary. [18]

5. An Act to Authorize the Acquisition of Additional Land in the City of Medford, Oregon, for Use in Connection with the Administration of the Crater Lake National Park (47 Stat. 156--May 14, 1932)

The Medford property acquired by the park in 1924 had become inadequate for park needs by 1932. The Park Service had built a warehouse (46 x 80 feet) on lot 3, block 2 of the central subdivision of the town which had been acquired in 1924. Each winter virtually all park equipment was taken to this property to be overhauled and placed in condition for the next season's operation. By 1932 the storage space for this equipment had become inadequate and the warehouse and yard greatly overcrowded, causing considerable delay and inconvenience in maintenance operations.

The lot (lot 4, block 2) adjoining the warehouse property became the property of Medford in the early 1930s. Park Superintendent Solinsky began negotiating with town authorities concerning donation of the lot to the Park Service for use in connection with the existing warehouse site. Assessments and interest against the lot amounted to nearly $1 ,000, and before the town could donate the lot it would be necessary for the matter to be placed on the ballot in the November election. The cost of the ballot measure was estimated to cost $300. However, it would be possible for the town to sell the lot to the government without the approval of the citizenry, and, accordingly, town officials offered the lot for the nominal sum of $300. [19]

On March 8, 1932, Representative Willis C. Hawley of Oregon introduced a bill (H.R. 10284) to authorize acquisition of the additional lot by the federal government. The bill read:

That the Secretary of the Interior be, and he is hereby, authorized to acquire on behalf of the United States for use in connection with the present administrative headquarters of the Crater Lake National Park, that certain tract of land in the city of Medford, Jackson County, Oregon, adjoining the present headquarters site and described as lot 4, block 2, central subdivision to said city of Medford, Oregon, which tract of land has been offered to the United States for the purpose aforesaid by the city of Medford, Oregon, free and clear of all encumbrances for the consideration of $300.

SEC. 2. That not to exceed the sum of $300 from the unexpended balance of appropriations heretofore made for the acquisition of privately owned lands and/or standing timber within the national parks and national monuments be, and the same is hereby, made available for the acquisition of land herein authorized. [20]

The bill encountered little opposition on its legislative course through Congress. After receiving endorsement by Secretary of the Interior Wilbur and Park Service Director Albright in mid-March, the House Committee on Public Lands recommended passage of the bill without amendment on March 28. [21] The House passed the bill on April 4 after which it was sent to the Senate. After being reported favorably without amendment by the Senate Committee on Public Lands and Surveys on April 26, [22] the bill passed the Senate on May 9. On May 14 the bill was signed into law (47 Stat. 156) by President Hoover. On March 7, 1933, the lot, comprising 0.13 acre of ground, was purchased and added to the park's property holdings. [23]

6. An Act to Amend an Act Entitled "An Act to Accept the Cession by the State of Oregon of Exclusive Jurisdiction over the Lands Embraced within the Crater Lake National Park, and for Other Purposes (49 Stat. 422--June 25, 1935)

The purpose of this legislation was two-fold. First, it provided for acceptance by the federal government of exclusive jurisdiction over the 973-acre south extension of the park from the State of Oregon. Second, it was designed to amend the Act of August 21, 1916 (39 Stat. 521) to allow the United States Commissioner for the park to live outside its boundaries. Since the park was closed each winter and the superintendent and other park officials maintained offices in Medford during those months, it was impracticable to require the commissioner to live within the park boundaries on a year-round basis.

The events precipitating this issue surrounded the death of William G. Steel on October 20, 1934. Steel had served as commissioner from 1916 to 1934 and at his death his daughter, Jean G. Steel, was appointed to succeed him effective October 25, 1934. On January 26 of the following year the Comptroller General of the United States ruled that no salary was payable for any period during which the commissioner did not reside within the boundaries of the park, thus disallowing the claim of Jean G. Steel for her salary from October 25 to December 31, 1934. A claim for the salary of William G. Steel from September 1 to October 20 was also disallowed. Thus the new legislation was proposed to allow payment of the accrued salaries. [24]

Senator Charles L. McNary of Oregon introduced the necessary legislation (S. 2185) on March 7, 1935. The bill contained language to amend three sections of the earlier legislation:

SEC. 6. That the United States District Court for Oregon shall appoint a commissioner, who shall reside within the exterior boundaries of the Crater Lake National Park or at a place reasonably adjacent to the park, the place of residence to be designated by the Secretary of the Interior, and who shall have jurisdiction to hear and act upon all complaints made of any violations of law or of the rules and regulations made by the Secretary of the Interior for the government of the park and for the protection of the animals, birds, and fish, and objects of interest therein, and for other purposes authorized by this Act.

SEC. 2. That section 9 of the said Act be amended by striking out the words, "Provided, That the said commissioner shall reside within the exterior boundaries of said Crater Lake National Park, at a place to be designated by the court making such appointment.

SEC. 3. Any commissioner heretofore appointed under authority of the said Act shall be entitled to receive the salary provided by law, which may have accrued at the date this Act becomes effective, without regard to whether such commissioner or commissioners may have resided within the exterior boundaries of the Crater Lake National Park. [25]

The bill received quick endorsement by Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes, and the Senate Committee on Agriculture and Forestry reported favorably on the bill without amendment on April 15. [26] After being approved by the Senate on May 1, the bill was referred to the House where the Committee on Public Lands undertook its consideration on May 3. Earlier on April 17 Representative James W. Mott of Oregon had introduced an identical bill (H.R. 7566), which had been referred to the House Committee on Public Lands. Thus, on May 9 the committee reported favorably on H.R. 7566 without amendment. [27] On June 15 the House passed S. 2185 in lieu of H.R. 7566, and on June 25, 1935, the bill was signed into law (49 Stat. 422) by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

7. An Act to Provide for the Resolution of Mining Activity Within, and to Repeal the Application of Mining Laws to Areas of the National Park System, and for Other Purposes (90 Stat. 1342--September 28, 1976)

On September 18, 1975, Senators Metcalf, et al. (co-sponsors were Senators Dale Bumpers, Alan Cranston, Mark Hatfield, Henry Jackson, J. Bennett Johnston, Robert Packwood, Richard Schweiker, and John Tunney) introduced legislation (S. 2371) that dealt with the only areas of the National Park System in which mineral development was permitted under the Mining Law of 1872--Crater Lake and Mount McKinley national parks, Death Valley, Glacier Bay, and Organ Pipe Cactus national monuments, and Coronado National Memorial. This was done since the level of technology of mineral exploration and development had changed radically in recent years and continued application of the mining laws of the United States to National Park Service areas often conflicted with the purposes for which those parks were established. The sponsors of the bill asserted that all mining activities in the National Park System should be conducted in such a manner as to prevent or minimize damage to the environment and other resource values, and in certain areas surface disturbance from mineral development should be halted temporarily while Congress determined whether or not to acquire any valid mineral rights which might exist in those areas.

Section 3 of the bill stated that "Subject to valid existing rights," various acts of Congress were to be amended or repealed to close the six aforementioned Park Service areas "to entry and location under the Mining Law of 1872." In this section "the first proviso of section 3 of the Act of May 22, 1902 (32 Stat. 203; 16 U.S.C. 123), relating to Crater Lake National Park, was amended by deleting the words 'and to the location of mining claims and the working of same.' "

Section 7 of the bill provided that within four years after the enactment of the legislation the Secretary of the Interior would determine the validity of any unpatented mining claims within Crater Lake National Park, Coronado National Memorial, and Glacier Bay National Monument. The secretary was to submit to Congress recommendations as to whether any valid or patented claims should be acquired by the United States.

Section 8 of the proposed legislation provided that all mining claims under the Mining Law of 1872 which were in National Park Service areas were to be recorded with the Secretary of the Interior within one year after the effective date of the act. Any mining claim not recorded during that period would be presumed to be abandoned and declared void. Such recordation would "not render valid any claim which was not valid on the effective date of this Act." [28]

The bill was referred to the Senate Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, and on December 16, 1975, the committee reported favorably on the proposed legislation with amendments. Relative to Crater Lake the committee found that:

There are no unpatented or patented mining claims or locations within the park and, thus, there is currently no mining activity within the park.

As part of its report the committee printed a letter from Assistant Secretary of the Interior Nathaniel Reed to its chairman Henry M. Jackson on October 6. One paragraph of the letter concerned Crater Lake National Park:

This National Park may be technically open to location, entry, and patent under the mining laws of the United States. There are no unpatented or patented mining claims or locations within the park and, thus, there is currently no mining activity within the park. The Act of May 22, 1902 (32 Stat. 202) that established Crater Lake National Park stated that "Crater Lake National Park shall be open, under such regulations as the Secretary of the Interior may prescribe, to all scientists, excursionists, and pleasure seekers and to the location of mining claims and the working of the same." However, the Act of August 21, 1916 (39 Stat. 522), provided that the Secretary of the Interior shall make rules for the protection of the property therein "especially for the preservation from injury or spoilation of all timber, mineral deposits other than those legally located prior to the date of enactment of this Act, natural curiosities, or wonderful objects within said park. . . . Since the Act of 1916 did not specifically repeal the mining languages in the 1902 Act, there is some confusion in the law as to whether Crater Lake National Park is open to mining activity. [29]

The bill was debated at length in the Senate on February 3 and 4, 1976, and after several amendments (none of which affected Crater Lake) were adopted it was approved by that chamber on the 4th. The bill was sent to the House where the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs submitted a favorable report with amendments on August 23. [30] After being amended (none of which affected Crater Lake), the bill passed the House on September 14. Three days later the Senate concurred in the House amendments, and on September 28 the bill was signed into law (90 Stat. 1342) by President Gerald R. Ford. [31]

8. An Act to Revise the Boundary of Crater Lake National Park in the State of Oregon, and for Other Purposes (94 Stat. 3255--December 19, 1980)

On February 20, 1980, Senator Mark O. Hatfield of Oregon introduced legislation (S. 2318) to revise and expand the boundaries of Crater Lake National Park. Hatfield noted in the Congressional Record that the bill was designed "to further protect a national park which houses the deepest and possibly the most pure body of fresh water in the United States. He went on to present a lengthy speech explaining the rationale behind his bill:

In contrast to most other natural lakes, Crater Lake has no influent or effluent streams to provide continuing supplies of oxygen, nutrients, and large volumes of fresh water. Thus, water entering the lake comes directly from rainfall or snowmelt and leaves by means of evaporation or seepage through fractures in the caldera wall. Its purity is thus highly susceptible to man-caused pollution, which would not be "flushed" by water moving through the lake.

Several other ecological communities of importance exist within the park. It is to these features that I address my concern. This legislation provides, through a moderate expansion of the park, protection for key natural features associated with the geological formations in the park. On the east, the boundary modifications would include the Sand Creek Drainage, a canyon which contains geological pumice formations commonly referred to as "The Pinnacles," as well as Bear Butte, a significant scenic feature viewed from within the park. To the north, the proposed boundary incorporates the lower slopes of Timber Crater, and the Desert Ridge-Boundary Springs ecological units. Sphagnum Bog, an area to the west of the park, which exhibits a flora of mosses and herbs, is fed by Crater Springs. The proposal incorporates that spring, as well as the scenic Spruce Lake into the park. Just outside the southwest corner of the park is a unique area known as Thousand Springs. This feature also would be included in the park, if the Senate enacts this legislation.

Total acreage of the existing park is 160,290. My proposal would add approximately 22,890 acres to that figure, all of which are presently managed by the U.S. Forest Service. There is no private land involved in this proposal.

I might also note . . . that the major portion of this acreage was recommended last year by the administration for additional protection as wilderness through the Forest Service evaluation of roadless areas, known as RARE II . After intensive evaluation by myself and my staff, I agreed that these lands merit protection. However, because of their size and relationship to the geological features of the park, I believe it makes sense that these lands be managed by the National Park Service.

. . . a glance at the map indicates that the straightlined boundaries drawn 80 years ago did not follow the ecological features of the land area, but simply carved a rectangle to assure protection of the lake. If we were to draw boundaries today which reflect natural ecological features related to those in the existing park, I believe they would clearly follow those proposed in this legislation. . . . [32]

The proposed additions by Hatfield comprised 8,000 acres less than a proposal by the administration of Jimmy Carter in 1979 to designate lands (RARE II) adjacent to the park boundaries as wilderness managed by the U.S. Forest Service. Lands deleted by Hatfield included acreage in the Diamond Lake area north of the park to permit its continued use by snowmobiles and land south of the park because much of it was in the wilderness bill and some was part of a proposed exchange with the state. Hatfield's bill was based on the recommendations of Park Service and Forest Service officials that had met at his instigation to come up with manageable boundaries that would contain features that could be placed in the park. [33]

As introduced S. 2318 provided for the repeal of the Act of May 14, 1932 (47 Stat. 155). Provisions in the bill included:

. . . The boundary of the park shall encompass the lands, waters, and interests therein within the area generally depicted on the map entitled, "Crater Lake National Park," numbered 106-80,001, and dated February, 1980, which shall be on file and available for public inspection in the office of the National Park Service, Department of the Interior. Lands, waters, and interests therein within the boundary of the park which were within the boundary of any national forest are excluded from such national forest and the boundary of such national forest is revised accordingly. [34]

The bill was referred to the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources, which had Henry M. Jackson of Washington as its chairman. On September 18, 1980, the committee reported favorably on the bill and recommended passage without amendment. In its report the committee observed that the purpose of the proposal was to expand the park "by some 22,890 acres, in order to protect important natural features and to establish a more identifiable boundary."

The committee report contained a lengthy section on the background and need for the bill. This section read in part:

Since the lake was viewed as the primary feature of the park, straight line boundaries, generally following land survey section lines, were drawn to assure protection of the lake and to delineate the park. These boundaries did not follow the natural ecological features of the land area nor did they include certain significant natural features associated with the geological formations in the park.

In April of 1979, the administration transmitted to Congress its recommendations for management of some 62 million acres of roadless national forest lands. Included in its wilderness recommendations was a 30,000-acre strip of U.S. Forest Service land which surrounds Crater Lake National Park. These lands were recommended by the Forest Service for designation as wilderness.

The committee, however, felt these lands that are geographically related to the features of the park should be managed by the National Park Service, rather than having a narrow strip surrounding the park managed in wilderness by another agency.

In addition, the proposed minor changes would improve the park boundary by more closely following the topographical features of the land area. It would also add to the park key natural features associated with the geological formations in the park. . . .

Since the bill would have the effect of transferring lands from the U.S. Forest Service to the National Park Service no additional administrative costs were expected to be incurred by the federal government as a result of the bill's passage. It was estimated that it would cost $300,000 to post the revised boundary line. The removal of the lands involved from the national forest system would reduce the long-term programmed harvest of the surrounding forest by approximately 800,000 board feet per year, thus causing a long-term reduction in timber receipts of some $200,000 annually. [35]

A companion bill, Title I of H.R. 8350, was introduced by Representative Philip Burton in the House of Representatives on November 17, 1980. The Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, to which the bill was referred, was discharged from consideration, and H. R. 8350 passed the House on November 19.

S. 2318 was brought before the Senate for consideration on December 4, 1980. During debate a section was added to the bill concerning provisions to make possible more effective protection of the Alpine Lakes Wilderness and more comprehensive management of the Alpine Lakes Area in Washington as established by the Alpine Lakes Area Management Act of 1976. The bill, as amended, passed the Senate on December 4 and the House the following day. The bill was signed into law (94 Stat. 3255) by President James E. Carter on December 19, 1980. [36]

9. An Act to Correct the Boundary of Crater Lake National Park in the State of Oregon, and for Other Purposes (96 Stat. 709--September 15, 1982)

On May 6, 1981, Senator Hatfield submitted a bill (S. 1119) to "correct the boundary of Crater Lake National Park." The 22,890-acre addition to the park in 1980 included a 480-acre parcel of timber on the west boundary which was scheduled to be cut under a contract entered into by the U.S. Forest Service in 1976. Thus, Hatfield introduced S. 1119 by stating:

Based on field examinations by Forest Service and Park Service personnel, a boundary line based on the above criteria was developed and reviewed by both agencies. The line finally adopted included a small parcel of timber on the west boundary which was scheduled to be cut under a contract entered into in 1976. Field personnel of the National Park Service were not aware that the added lands were subject to an outstanding timber sale. However, neither the sponsor of the legislation nor the Park Service wished to prohibit the exercise of valid contractual rights to cut timber by the boundary change.

Timber harvesting is not permitted within Crater Lake National Park. Accordingly, this legislation would remove from the park about 480 acres, of which 39 acres are scheduled to be harvested and 58 acres have already been cut during 1960-66. The new boundary line will conform the boundary to that which was intended by all parties when the 1980 legislation was considered. [37]

As introduced the bill read:

That (a) the first section of the Act entitled, "An Act reserving from the public lands in the State of Oregon, as a public park for the benefit of the people of the United States, and for the protection and preservation of the game, fish, timber, and all other natural objects therein, a tract of land herein described, and so forth", approved May 22, 1902 (32 Stat. 202), as amended, is further amended by revising the second sentence thereof to read as follows: "The boundary of the park shall encompass the lands, waters, and interests therein within the area generally depicted on the map entitled, 'Crater Lake National Park, Oregon,' numbered 106-80-001-A, and dated March 1981, which shall be on file and available for public inspection in the office of the National Park Service, Department of the Interior."

(b) Lands, waters, and interests therein excluded from the boundary of Crater Lake National Park by subsection S(a) are hereby made a part of the Rogue River National Forest, and the boundary of such national forest is revised accordingly. [38]

The proposed legislation was referred to the Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources for consideration. Meanwhile, on May 19, Representative Denny Smith of Oregon introduced an identical bill (H.R. 3630) in the House, where it was referred to the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs.

In response to the request of Senate committee chairman James A. McClure of Idaho Under Secretary of the Interior Donald P. Hodel responded with the department's position on the bill on September 23. Recommending enactment of the bill Hodel urged passage "to remove the approximately 480 acres of land from Crater Lake National Park, and to make those lands a part of Rogue River National Forest." On October 7 the committee issued a report recommending passage of the bill without amendment. [39]

The bill passed the Senate on October 21 and was sent to the House where it was referred to the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs the following day. Meanwhile on October 16 the House Subcommittee on Public Lands and National Parks had held hearings on H.R. 3630. On November 19 the subcommittee adopted S. 1119 in lieu of H.R. 3630 and reported its findings to the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs. Among its recommendations, which were accepted by the full committee, were amendments authorizing the Secretary of the Interior to initiate studies and actions to assure the retention of Crater Lake's natural pristine water quality and to designate part of the Cumberland Island National Seashore as wilderness, the text relating to the latter issue becoming Section 2 of the bill.

The committee issued its report on December 10, 1981, recommending passage of the bill as amended. The section of the bill pertaining to Crater Lake included the language originally introduced by Hatfield. Furthermore, a provision was added relative to water quality testing of the lake:

. . . The Secretary of the Interior is authorized and directed to promptly instigate studies and investigations as to the status and trends of change of the water quality of Crater Lake, and to immediately implement such actions as may be necessary to assure the retention of the lake's natural pristine water quality.

Within two years of the effective date of this provision, and biennially thereafter for a period of ten years, the Secretary shall report the results of such studies and investigations, and any implementation actions instigated, to the appropriate committees of the Congress.

The committee felt that Section C was important in that the lake had "long been considered to contain some of the deepest and most pure water in the world." Research conducted in recent years had indicated "that water clarity of the lake" had been "reduced by 25% over the last 13 years." Thus, the committee was concerned that further studies be conducted and steps taken to assure the purity and clarity of the water in Crater Lake. [40]

The Senate concurred with the House amendments on August 19, 1982. Thereafter, it was signed into law (96 Stat. 709) by President Ronald Reagan on September 15. [41]

As congressional debate on this legislation indicated there was increasing concern about the clarity of the water in Crater Lake. Independent studies of Crater Lake during the late 1970s and early 1980s suggested that the lake had decreased in transparency and that the species composition and distribution of the phytoplankton had changed relative to results from short-term studies conducted between 1913 and 1969. Evaluation found that the transparency and phytoplankton data were inadequate for the basis of any definitive conclusions on whether long-term changes had occurred in lake water quality. To build on the existing baseline data, however, the National Park Service initiated a limnological study of Crater Lake during the summer of 1982 while the aforementioned legislation was being debated in Congress. [42]

As a result of this legislation a comprehensive Crater Lake Limnological Studies program was initiated during the summer of 1983. The broad objectives of the program were to (1) develop a reliable limnological data base for the lake for use as a benchmark or basis for future comparison; (2) provide a better understanding of physical, chemical, and biological characteristics and processes of the lake; and (3) establish a long-term monitoring program to examine the characteristics (i.e., temperature, pH, visibility, chlorophyll, and phytoplankton levels) of the lake through time. The purpose of the applied limnological investigations was to examine changing lake conditions and carry out studies to identify the causes of any changes that were found to exist. [43]

Further refinements were made to the Crater Lake limnological program in 1985 and 1986. New studies were initiated to determine the relationship between the fisheries population and the various lake organisms. During the summer of 1985 a research boat plan was approved and a boathouse was constructed on Wizard Island for the purpose of storing the three lake research boats--Boston Whaler, Gregor Pontoon Boat, and Livingston. [44]

By 1986 the limnological program at Crater Lake had become further institutionalized. First, a "Position Statement and Operational Plan for Winter and Spring Research on Crater Lake" was adopted, outlining standardized sampling and logistical procedures for lake research during the winter and spring. [45] Second, the Crater Lake park staff developed a comprehensive, interdivisional limnological program designed to monitor the lake water quality, protect the entire caldera ecosystem, and keep the public informed concerning lake research findings. The interdivisional program provided for clearly defined roles of various personnel and offices, including the Pacific Northwest Regional Office, principal park investigator, and park administrators, resource management specialists, biotechnicians, rangers, and interpreters. [46]

As the limnological program got underway a new threat to the water quality of Crater Lake surfaced. This threat stemmed from approval given in 1985 to the California Energy Company, a Santa Rosa-based geothermal production company, to test drill for geothermal resources in the Winema National Forest adjacent to the park. An environmental assessment prepared for the Bureau of Land Management and the U.S. Forest Service in 1984 foresaw no environmental impacts on the park as a result of incorporating various Park Service proposals: measurement of noise levels; testing of surface water for contamination that might occur during drilling; use of equipment to deter drill-hole blowouts; surveys to ensure no drilling inside the park boundaries; and testing of water from the drill holes to see if its chemistry matched that of Crater Lake. Despite these provisions, however, the Park Service continued to be concerned since no one was sure about the possible substrata connections between the geothermally heated waters and Crater Lake. This concern was based on fears that by tapping these hot waters, which would be only a few miles from Crater Lake, developers might jeopardize the water quality of the lake itself. [47]

B. WILDERNESS DESIGNATION PROPOSALS

A National Wilderness Preservation System, established by Congress on September 3, 1964, has had a significant impact on administration and management of Crater Lake National Park. The establishing act of the system (Public Law 88-577) stated that it was "the policy of Congress to secure for the American people of present and future generations the benefits of an enduring resource of wilderness." Within ten years the Secretary of the Interior was to:

review every roadless area of five thousand contiguous acres or more in the national parks, monuments and other units of the national park system . . ., under his jurisdiction of the effective date of this Act and shall report to the President his recommendation as to the suitability or nonsuitability of each such area . . . for preservation as wilderness.

The National Wilderness Preservation System was "to be composed of federally owned areas designated by Congress as 'wilderness areas'." The law defined a wilderness as

an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain. An area of wilderness is further defined to mean . . . an area of undeveloped Federal land retaining its primeval character and influence, without permanent improvements or human habitation, which is protected and managed so as to preserve its natural conditions and which: (1) generally appears to have been affected primarily by the forces of nature, with the imprint of man's work substantially unnoticeable; (2) has outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation; (3) has at least 5,000 acres of land or is of sufficient size as to make practicable its preservation and use in an unimpaired condition; and (4) may also contain ecological, geological, or other features of scientific, educational, scenic, or historical values.

Areas included in the wilderness system would continue to be managed by the agencies having jurisdiction over them. [48]

Studies were conducted at Crater Lake National Park for several years, culminating in the preparation of a Wilderness Proposal in October 1970. [49] Five roadless areas within the park totaling some 151,100 acres were studied. Four of the areas were located, one in each quadrant of the park, and the fifth encompassed Crater Lake itself. Each of the four areas had, according to the proposal, "a remarkable variety of natural features." The "forested crater slopes and river drainages" had "retained much of their original wilderness character ever since the park was established in 1902." The proposal stated further:

The park is almost entirely surrounded by national forest lands managed by the Forest Service for multiple use, primarily timber production. Logging roads run close to the park boundary in many places. The forest on the east is of poor quality; it was clearcut in the past, but is now selectively cut. Along much of the west boundary, the area outside the park has been logged to within 100 yards of the park. Logging in the national forest to the north of the park has not been very active because of the forest type there. National forest land lying immediately southwest of the park has not been logged, and the Forest Service is administering this area in a primitive condition.

The proposal contained descriptions of the four areas in the park recommended for wilderness designation. The four areas comprised a total of some 104,200 acres. Preliminary Wilderness Proposal No. 1 consisted of some 31,500 acres of an approximate 38,300 acres in the northeast roadless area. This area had the following boundaries and predominant visitor uses:

This roadless area extends from the north entrance eastward to the northeast corner of the park, then southward past the eastern slopes of Mt. Scott to the Pinnacles area. Its western boundary extends from the Pinnacles area along the Pinnacles Road, the Rim Drive, and the North Entrance Road. The northeast roadless area varies in width from 1-1/2 to 8 miles along its 15-1/2-mile length. . . .

Predominant visitor uses in this roadless area are hiking, fishing, and limited wilderness camping. The region is too dry for extensive back-country use. A 2-1/2-mile trail to the summit of Mt. Scott is maintained for hikers.

Preliminary Wilderness Proposal No. 2 consisted of some 18,000 acres of an approximate 21,400-acre roadless area in the southeast portion of the park. The boundaries and features of this area were:

The southeast roadless area extends from the Pinnacles Road at the eastern boundary southward to the southeast corner of the park, and then along the south boundary westward to the "panhandle" of the park. Its western and northern boundaries are the South Entrance, Rim Drive, and the Pinnacles and Grayback Motor Nature Roads. The area is an irregularly shaped 5- by 9-mile section. . . .

Annie Creek and its tributaries drain the western part of the area. Within its canyons are fragile biological communities and unusual geologic formations, including columnar-jointed scoria and pinnacles formed by differential erosion in "fossil fumarole" areas.

Bisecting this area is Sun Creek, a major stream that provides one of the principal fisheries of the park.

Preliminary Wilderness Proposal No. 3 comprised some 12,500 acres of an approximate 19,500-acre roadless area in the southwest section of the park. This area was described:

The roadless area in the southwest section of the park consists of some 19,500 acres and extends from the South Entrance along the south and west boundary, the West and South Entrance Roads, and the Union Peak Motor Nature Road. Within the area is a plateau dominated by Matterhorn-like Union Peak, with deep Red Blanket Canyon as a feature of the southwest corner. Several cones and other volcanic features are also of geologic interest. Plant cover represents three life zones, and varies from the sparcity of a pumice desert to the lushness of a mature forest; and there are lower elevation plants found in the Red Blanket Creek drainage.

Union Peak, the dominant geological feature of this area, at an elevation of 7698 feet, is an outstanding remnant plug of one of the major Pliocene shield volcanoes in the region.

Whitehorse Pond contains salamander populations which have been subjected to intensive scientific study. A small but growing herd of elk regularly occupies the country surrounding Union Peak.

Preliminary Wilderness Proposal No. 4 consisted of some 42,200 acres of an approximate 50,900-acre roadless area in the northwest section of the park. This area was described:

The largest roadless area in Crater Lake is the northwest section of the park. It is an area . . . from 4 to 7 miles wide and 13 miles long, and lies along the west slope of the Crater Lake caldera.

The Rogue River and several tributary streams originate in the series of springs within the western portion of the area.

Sphagnum Bog, near the western boundary, is the nucleus of a bog development unique to the area and rare throughout the entire region. Insectivorous plants of several species flourish here, and the entire community forms a distinct contrast to its surrounding area. Here, as in the park's other roadless areas, there are forests of whitebark pine, mountain hemlock, and western white, lodgepole, and ponderosa pines at the higher to lower elevations.

Boundary Springs on the north boundary forms the headwaters of the Rogue River. These waters spring forth most unexpectedly from the otherwise-arid ground of the area, splash downward over the irregular terrain into a stream which leads north away from the park, producing an aquatic scene of great esthetic appeal.

While the lake was studied for possible wilderness designation, it was not recommended for the system. Boat use and lakeshore development at Cleetwood Cove and Wizard Island were found to be incompatible with the requirements for such designation. [50]

As required by the Wilderness Act, public hearings were held on the Crater Lake Wilderness Proposal in Klamath Falls and Medford in January 1971 . Various proposals were set forth by public agencies and private organizations at the hearings. The Wilderness Society introduced an alternate proposal to enlarge the wilderness designations in the park by opposing the proposed Union Peak Motor Nature Road and the 1/8-mile management zones along the park boundary and recommending that a 20,000-acre Caldera Wilderness, encompassing Crater Lake, the islands, and the undeveloped rimlands, be included in the wilderness designation. Major organizations that generally supported or had similar positions to that of the Wilderness Society included the Izaak Walton League of America, Friends of Three Sisters Wilderness, National Parks and Conservation Association, Oregon Wildlife Federation, and Sierra Club. [51]

A "seasonal" wilderness concept was proposed by the Oregon Environmental Council whereby two wilderness boundaries would be established for the park. One boundary would be designated during the summer visitor-use season, and a different boundary would be established for "winter wilderness," closing the entire northern part of the park to all motorized vehicles during the winter months.

The National Park Service proposal, however, was supported by the Oregon State Game and Fish commissions and seven other public agencies. Among the most important supporters of the Park Service was the U.S. Forest Service whose national forest lands surrounded the park.

For the next several years the National Park Service studied the oral and written statements presented at the hearings and restudied the question of management needs. In February 1974 the final wilderness recommendations for Crater Lake were approved by NPS Director Ronald Walker. Three additions, totaling 18,200 acres, were recommended to supplement the earlier proposal. Some 7,300 acres were added to Preliminary Wilderness Proposal No. 3 as a result of deleting the proposed Union Peak Motor Nature Road and closure to vehicular traffic of the fire roads in the Union Peak area, portions of which would become the route of the Pacific Crest Trail. The 1/8-mile-wide management zone, totaling 4,400 acres, was recommended for addition to the wilderness designation since it was "believed that actions needed for the health and safety of wilderness travelers, or for the protection of the wilderness area, utilizing the minimum tool, equipment or structure necessary, may take place within the wilderness." Wilderness Unit 5, comprising 6,500 acres along the rim area on the southern side of the lake within the Rim Drive and the caldera walls, except for the Cleetwood Cove access and service corridor, was also recommended for designation. With these additions the total acreage of recommended wilderness designation was approximately 122,400. [52]

The wilderness recommendation was sent by President Richard M. Nixon to Congress on June 13, 1974. Pending congressional action to establish formally the areas as designated wilderness, the areas were managed in accordance with the guidelines prescribed in the Wilderness Act and the National Park Service wilderness management policies. [53]

In 1980 Public Law 96-553 (94 Stat. 3255) provided for the qualification of additional acres for designation as wilderness in Crater Lake National Park. This law added nearly 16,000 acres from U.S. Forest Service RARE II lands, resulting in a total proposal of some 138,310 acres in 1981 . The additional acreage was developed using a zone concept based on straight lines drawn on the park map. A serious drawback of that technique, however, was the difficulty of determining where on the ground nonwilderness ended and wilderness commenced.

The current proposal for wilderness designation in Crater Lake National Park, according to its 1986 Statement for Management, incorporates three principal concepts. These are that: (1) nonwilderness extends 200 feet beyond the edge of all development including motor vehicle roads; (2) all park areas not currently falling within this 200-foot corridor around development are recommended for wilderness designation; and (3) the entire lake surface is recommended for willderness designation except for four acres at Cleetwood Cove and four acres at Wizard Island where boat docking and storage occur. The Park Service has taken the position that the existence and continued use of the concessioner-operated tour boats and the lake research boats do not preclude the lake surface from wilderness designation (NPS Management Policies, VI-7, 1978). Thus, the current acreage within the park recommended for wilderness designation is 166,149. [54]

C. ACQUISITION OF MAJOR PARK INHOLDINGS

When Crater Lake National Park came under the administration of the National Park Service there were nearly 2,000 acres of private inholdings in the reservation. The existence of private inholdings in the national parks was viewed by NPS officials as an impediment to effective management. Thus, NPS Director Mather made it a priority of his administration to acquire such inholdings. In terms of Crater Lake National Park the two principal private inholdings to be acquired were the Yawkey and Gladstone tracts.

1. Yawkey Tract

Using Public Works Administration (PWA) funds the federal government acquired a fee simple title to 1,872.36 acres of land owned by the Yawkey Lumber Company in the southeastern corner of the park on August 7, 1940. The acquisition under condemnation proceedings, which amounted to $6,560.26 or $3.50 per acre, was subject to the right of the Algoma Lumber Company to remove the timber on approximately 123 acres of land in the SE 1/4 of Section 8 and the N 1/2 NE 1/4 of Section 17. Final judgment on the transaction was rendered on December 4, 1940. [55]

The purchase of the Yawkey Tract was a culmination of sixteen years of effort by the National Park Service. In May 1924 NPS Director Mather expressed interest in acquisition of the property. Three months later C.C. Yawkey, President of the Yawkey Lumber Company with offices in Wausau, Wisconsin, responded by offering a property exchange:

The land which we own in the Park amounts to nearly 2000 acres, and applying the stumpage price at which land has been sold both on the Indian Reservation and in the National Forests, the value of this timber would be something like $250,000, and you can readily see that we would not feel warranted in deeding this to the Government.

However, we have this suggestion to make: The Government has land adjoining our tract in the Cascade National Forest, which, as I understand it, is on both sides of our tract, and if there is anything that adjoins us so that it would leave our timber in a compact tract, we would be willing to make an exchange thousand for thousand and value for value.

There is also timber along our east line in the Klamath Indian Reserve for which we would be willing to trade. [56]

The proposal was not acceptable to the Park Service, and on September 25, 1924, Mather informed Yawkey:

That while your land is nominally within the Park it is not in a location which receives any tourist travel. Under the circumstances it seems advisable not to attempt anything in the way of a trade as you suggested. [57]

Discussions concerning the future of the Yawkey Tract lay dormant until February 1932. At that time Jackson F. Kimball of Klamath Falls, who was managing the local affairs of the Yawkey Lumber Company, sent a letter to Superintendent Solinsky suggesting that an effort be undertaken to change the boundaries of Crater Lake National Park to exclude the Yawkey Tract. Among his reasons for such a recommendation were:

I understand that there is some possibility that a Bill may be introduced in the present session of the Congress for a change in the boundaries of Crater Lake National Park.

Because of the possibility of such legislation it has occurred to me that it might be well to state to you, as the representative of the Park Service, the attitude of the Yawkey Lumber Company in reference to this matter. This Company holds some 2000 acres of land which lie in the southerly portion of the Crater Lake National Park, together with 14,000 acres outside the Park boundaries. The tract is almost entirely surrounded by lands belonging to the Federal Government, i.e., Klamath Indian Reservation, Crater National Forest and Crater Lake National Park.

The size of the tract and the quality of the timber now in the ownership of the Yawkey Lumber Company represents a most attractive operation for lumbering when and if the market conditions justify the expense of constructing a railroad to open this up. It is important however to bear in mind that it is absolutely essential, from the standpoint of the Yawkey Lumber Company, that there shall be no reduction in the volume of stumpage. The present volume represents the minimum for profitable operation . . . .

As the matter now stands it seems apparent that the Park Service would naturally prefer not to have ownership in any lands within the Park vested in a private owner. Certainly the Yawkey Lumber Company could not afford to sell except at a price which would represent compensation for not only the timber but for all the other losses accruing to the balance of its property. This in my judgment would set up a prohibitive price.

The obvious action, affording the least injury to all parties concerned, would seem to be to change the National Park boundaries to exclude the lands of the Yawkey Lumber Company from the Crater Lake National Park. [58]

After a negative response from the National Park Service negotiations concerning the Yawkey Tract lay moribund for another six years until March 1938 when Superintendent Leavitt again initiated correspondence with Kimball. As the merchantable lumber on the tract was being logged off, Leavitt suggested that when the timber was removed the company might be willing to donate the land to the government. He pointed out that the land would have little value to a lumber company after the merchantable timber was removed Thus, he suggested that, rather than continue to pay taxes on it or to grow a new stand of timber, the company might be willing to donate it to the government. [59]

In October 1938 a meeting and field inspection was arranged with park officials and representatives of the Yawkey Lumber Company. It was found that while the sugar pine and yellow pine on the tract had been harvested, the work had been done with a minimum destruction to the forest cover. The fire and logging roads followed acceptable planning models, and efforts had been made for the care of the remaining forest cover which was principally fir. Following the field inspection Kimball made a proposition to the Park Service. The proposal was described as follows by Superintendent Leavitt:

Within the holdings of the Yawkey Lumber Company within the park is a strip of land 40 acres wide and half a mile long, which belongs to the government. No one seems to know why this particular strip was not included in the original acquisition of lands by the Yawkey Lumber Company or their predecessors but apparently it was due to some error which left it out of the original filings. In any event, it belongs to the federal government, and now is an island within this logged-over area. Within this island are 1301 M feet BM of yellow pine timber and 135 M feet BM of sugar pine timber.

The Algoma Lumber Company of Modoc Point, Oregon, has purchased all of the merchantable timber owned by the Yawkey Lumber Company and have been cutting on the company's land within the park this last season. They have about one more season of cutting to do before all of the merchantable timber is removed. The Yawkey Lumber Company and the Algoma Lumber Company would like to secure the merchantable timber on this strip of government owned land. Mr. Kimball stated that Mr. Yawkey has agreed in return for the merchantable timber on this strip to deed the 1872 acres of their land within the boundaries of Crater Lake National Park. [60]

The proposal was quickly submitted to the NPS regional office in San Francisco for review. On October 24 Regional Forester Burnett Sanford responded to Kimball's proposal:

. . . I do not believe it is a good policy for a Park to exchange timber for cutover lands as it increases the area of devastation within the park. In this case there is some justification for such an exchange since the government land which Mr. Leavitt proposes to exchange is completely surrounded by cutover area and as nearly as I can tell from the map lies adjacent to the Park boundary.

I feel that a value of $3.50 per acre is high for cut-over land as the Forest Service seldom pays more than $2.50. Actually this land will be costing the Park closer to $7.50 per acre due to the contemplated agreement on our part to burn the slash over the whole area. There is a compulsory slash disposal law in Oregon so we would be relieving the lumber Company of an obligation which I estimate would cost them in the neighborhood of $7500.00 if the job is done without excessive damage to the remaining timber. If broadcast burning of slash is practiced the job could be done for $1,500 but the value of the cut-over lands will be greatly depreciated.

I imagine that the government could purchase these cut-over lands for $4,000 cash and that would appear to be the most satisfactory solution of the problem. [61]

On November 5 NPS Chief Counsel G.A. Moskey offered his comments on the proposed exchange. He stated that it violated the NPS establishing act in that moneys received for timber sold under its provisions were to be deposited in the Treasury Department. The funds could not be used for the purchase of privately owned lands within the park. [62]

In October 1939 the Public Works Administration allotted $8,000 for the purchase of the Yawkey Tract. The Park Service immediately asked for and received assurances from the company to postpone slash burning, pending the final consummation of the purchase. In view of the interest of the U.S. Forest Service in acquiring the remaining lands by the Yawkey Lumber Company, the Park Service began exploring the possibility of collaborating with that agency in negotiating for the entire holdings of the company. It was assumed that such a joint effort might result in a more reasonable purchase price. [63] When the Forest Service demurred because of what it considered to be an excessive asking price, the Park Service pushed ahead for final condemnation proceedings which culminated on August 7, 1940. [64]

On August 18, 1941, the U.S. Attorney General stated that the Yawkey case could be considered closed, as he was satisfied from an examination of the abstract of title and a review of the proceedings that a valid fee simple title to the land was vested in the United States of America. To provide access to the tract for fire protection purposes, it was necessary to build a 5-stringer standard log bridge 43 feet in length across Annie Creek. The construction of the bridge shortened the travel distance to the area by approximately 15 miles. Slash burning operations were carried on until winter snows stopped the work. [65]

2. Gladstone Land and Timber Company Tract

The Gladstone Land and Timber Company Tract, adjoining the Yawkey Tract, was acquired by the United States on August 21, 1941, in fee simple following completion of condemnation proceedings. PWA funds remaining from the allotment for the Yawkey Tract were used to make the purchase of 73.76 acres located in the southeastern corner of the park as follows:

Portion NE 1/4 NE 1/4; NW 1/4 NE 1/4; N 1/2 SW 1/4 NE 1/4; and Portion SE 1/4 NE 1/4 of Section 16, Township 32 South, Range 7 1/2 East, Klamath County, Oregon.

Acquisition of the property was finalized after more than three years of negotiations. With completion of the transaction all private inholdings in the park were extinguished. [66]

In March 1938 Superintendent Leavitt wrote to the Gladstone Land and Timber Company with offices in Gladstone, Michigan, expressing Park Service interest in acquiring its timber tract in the park. Park Service officials were interested in the tract since it was understood that the land was about to be logged. Leavitt noted:

. . . If this is true, would your company be willing to donate this land to the federal government after the timber has been logged off, so that the area might become an integral part of Crater Lake National Park. Some organizations have found it practicable to donate lands after the timber has been removed rather than to continue to pay taxes on cut-over lands or attempt to grow a new crop of timber.

It is the policy of the National Park Service to acquire all private holdings within the boundaries of its various national parks and monuments, but there are no funds for purchasing such lands and we have to look to individuals and organizations who are public spirited enough to donate their property or provide the funds with which purchases may be made. [67]

Some months later on October 20 Leavitt again wrote to the company expressing Park Service interest in its property. He observed that he had been mistaken about the timber prospects of the acreage, but that the Park Service was still interested in its acquisition:

The lands embraced in this tract were formerly covered with a good stand of timber, but fires have completely denuded the area, and the land is without commercial value except for some grazing. However, it does have value to Crater Lake National Park. Even the brush cover has park values, if not commercial values . . . .

When I wrote you last March, I was comparatively new to the position of Superintendent of Crater Lake and was of the opinion that this tract of land had merchantable timber on it. I have since learned that it is doubtful if there is a single merchantable tree on this property. As the taxes each year on the property come to a considerable amount, it occurs to me that you still might be willing to consider the suggestion I made that you donate this 73.36 acres to the government to become a part of Crater Lake National Park. [68]

Negotiations for federal acquisition of the property extended over the next eighteen months. In January 1940 the company indicated its desire to sell the property for $1,500. However, in June of that year a Park Service official appraised the property at the rate of $2.50 an acre. Finally on May 14, 1941, the company executed a stipulation in which it agreed to sell the property for the total appraised value of $183.40. Following condemnation proceedings valid title to the land was "vested in the United States of America in fee simple on August 21, 1941, pursuant to the provisions of an Act of Congress of February 26, 1931, with the right of possession on January 30, 1942." [69]

Following Park Service possession of the property Superintendent Leavitt responded to an inquiry by the Department of Justice of the State of Oregon relative to commercial activities or improvements on the tract. He observed that there was no

evidence of mining operations, agricultural improvements, manufacturing operations, or any ditch or reservoir used in connection with water rights; that there is not within my knowledge, or any outward evidence of any mining operation or vein or lode from which ore is being or has been extracted, which might be found to penetrate or intersect the premises . . . . [70]

D. UNSUCCESSFUL EFFORTS TO EXPAND PARK

BOUNDARIES

From the 1910s to the 1940s the National Park Service initiated a series of efforts to expand the boundaries of Crater Lake National Park. The primary purpose of these efforts was to enlarge the park to provide recreational opportunities and park facilities for visitors away from Crater Lake itself, and thus curtail or eliminate development that would mar the scenic and scientific qualities of the lake. A secondary purpose of the proposed expansion was to create an enlarged game preserve to protect the wildlife of the region. The focus of the expansion efforts was the Diamond Lake-Mount Thielson-Mount Bailey region to the north of the park and the Union Creek-Upper Rogue River Valley to the west.

In his first annual report NPS Director Mather recommended that the Crater Lake park boundaries should be extended northward to include the Diamond Lake region. This addition, according to Mather, would offer the tourist a variety of scenic features that "would compare favorably with the diversity of scenery in most of the very large mountain parks." Other advantages of the Diamond Lake extension were:

Diamond Lake lies a few miles north of the park in a region that is valuable for none other than recreational purposes. Fishing in the lake could be improved and the region around about it made attractive for camping. A chalet or hotel, operated in connection with the hotel on the rim of Crater Lake, could be constructed near Diamond Lake when travel to the park warranted these additional accommodations. It would be reasonable to expect that the majority of visitors to Crater Lake would not overlook an opportunity to see the wonderful scenic region to the northward. Besides Diamond Lake the proposed addition to the park would include Mount Thielson, a peak considerably over 9,000 feet in altitude and known as the "lightning rod of the Cascades," because during electric storms brilliant and fantastic flashes of lightning play about its needlelike summit.

Mather stressed that the addition of the Diamond Lake and Mount Thielson areas could "not be too strongly urged." A branch road from the main highway from Medford already made the Diamond Lake country accessible, and at some future time "a circle trip might be provided by the construction of a road from the north rim of Crater Lake to Diamond Lake."

A second park extension recommended by Mather was the Lake of the Woods region just south of the park. While the area had not been investigated by representatives of the National Park Service, it was "known to be an exceptionally beautiful region and valuable for scarcely anything besides park purposes." [71]

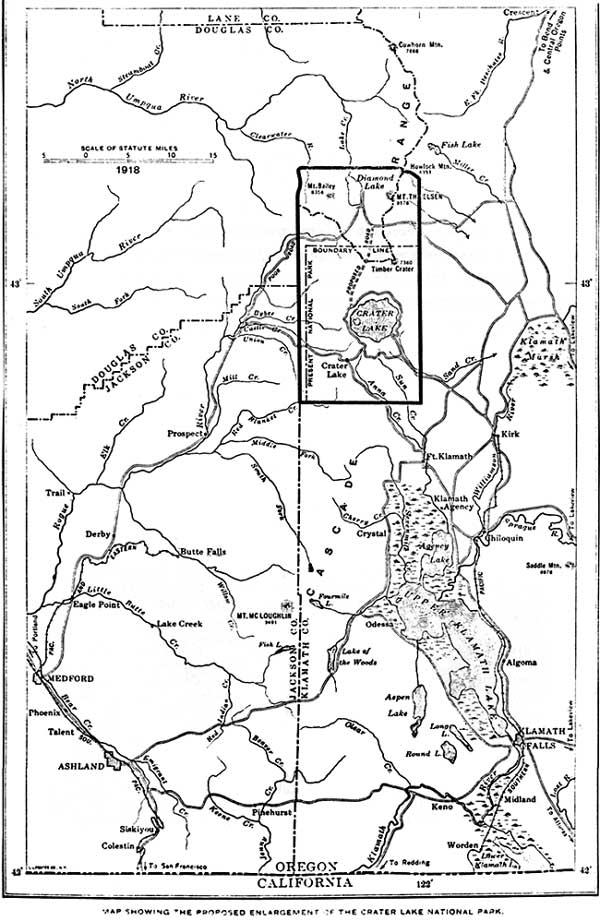

As a result of Mather's continuing lobbying efforts Senator McNary introduced legislation (S. 4283) on April 6, 1918, to provide for the transfer of some 92,800 acres of national forest land to the control of the National Park Service for addition to Crater Lake National Park. The proposed extension included a 3/4-mile strip of land on the western boundary as well as the principal nine-mile northward enlargement to include the Diamond Lake region (see map below). In support of this bill Mather noted: