|

CRATERS OF THE MOON

Administrative History |

|

Chapter 4:

LAND ISSUES AND LEGISLATIVE HISTORY

The monument's land and legislative histories intertwine. Most issues resolved through legislation reflect shortcomings in the area's founding document and revolve around boundary adjustments and land acquisitions. On the one hand, the majority of these were carried out through presidential proclamations rather than congressional acts and experienced little, if any, friction. On the other hand, some of these corrective measures gave rise to a host of new management problems and led to still more actions. And still other activities represented the normal course of Park Service management and the monument's mission. The recent expansion and park redesignation movement represents a special case.

THE NORTHERN UNIT

Added in 1928, the northern unit--the foothills of the Pioneer Mountains--has been one of the most contentious areas of monument management and at the center of numerous land and legislative issues. This northwestern section was acquired primarily for its watershed and springs to provide the monument with a domestic water supply, yet its boundaries also enclosed around five hundred acres of private claims--both grazing and mining--and an abundance of wildlife, giving rise to resource management concerns and legislative revisions.

|

THE 1928 PROCLAMATION: ADDING THE NORTHERN UNIT

Still to be worked out after the monument's creation was the question of boundaries. Establishment recognized the need to preserve and protect the lava formations along the rift zone, yet ignorance of the isolated district remained the primary barrier to designating appropriate lands. Work to rectify the problem began in 1925 when Max Gleissner of the USGS, with the assistance of the Idaho Bureau of Mines and Geology, conducted a topographical survey of the monument. In 1926 Stearns himself returned to complete his earlier geological reconnaissance and to begin a boundary revision study. In March 1927, he submitted his recommendations for boundary adjustments to the Park Service, enlarging the monument by about thirty-five square miles. Compared with the original boundary, this one gave the area "a more regular and geometric shape," hence making it "much more easily defined and administered." Furthermore, the document's main purpose was to exclude any undesirable land, and more importantly, to include "all of the scenic and [scientifically] important features that were left outside of the original boundary." [1]

In doing so, Stearns chose lands that were significant but also economically worthless; the geologist emphasized that except for a quarter mile, all of the proposed addition was covered with lava. The expanded boundaries, for instance, embraced such well-known sites as Amphitheater Cave, the Bridge of Tears, a large section of Vermillion Chasm, and all of the Blue Dragon Lava Flows. But "the most important and critical extension" was a "single square mile on the northwest corner of the monument." Section 34, T. 2 N., R. 24 E. contained Grassy Cone, a small section of the aa highway flow, and more significantly, access to a feasible water supply for camping. Except for scattered waterholes in the lavas, the monument was otherwise arid, and the geologist predicted water shortages and contamination, and hardship for tourists and campers alike. Thus, Stearns proposed that the Park Service create a campground in the more shaded and lush basin below Grassy Cone, file surface rights to Little Cottonwood Creek, build a reservoir at the spring above the Martin Mine, and pipe the water to monument land. Rather than have the Park Service acquire the water source for itself, Stearns believed his method would cause the least amount of conflict. He had chosen a section of the public domain that possessed mostly valueless timber, mineral, and grazing land, which was not the case a few miles north. [2]

Nonetheless, Stearns realized that soon the monument would require more water and a more secure source. Aware of this reality as well, the Park Service dispatched Civil Engineer Bert H. Burrell the following summer. Burrell believed that the monument's development and tourist appeal hinged on having an ample water supply. The one recommended by Stearns was not enough, and Burrell proposed expanding the boundary north to include the Little Cottonwood Creek watershed, namely the "numerous springs" of the stream's headwaters. In addition to water quantity, the engineer was concerned about water quality, asserting that his location would run less risk of contamination from livestock and wildlife than the chosen by Stearns. Several days after the engineer filed his July 21 report, water levels in the monument's waterholes dropped and in some cases disappeared. This crisis, as a result, caused the Park Service to immediately seek expansion, incorporating both Burrell's and Stearns' recommendations. [3]

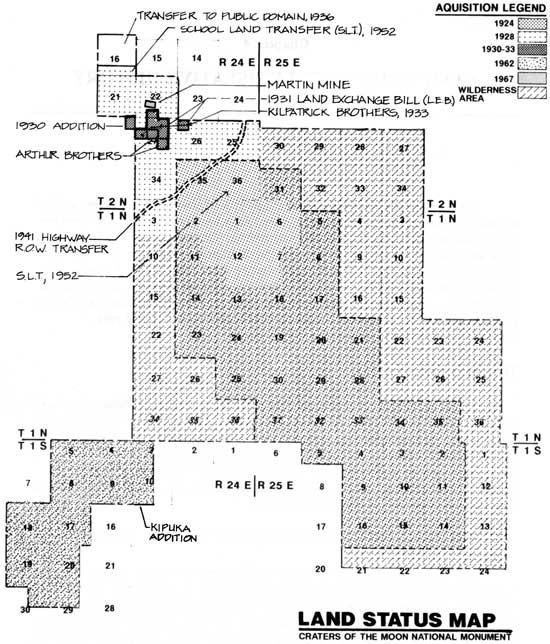

To this end, on July 23, 1928, President Calvin Coolidge enlarged Craters of the Moon National Monument "for the purpose of including...certain springs for water supply" as well as the addition of features of scientific significance. The proclamation increased the monument's size from thirty-nine to eighty-three square miles. The expanded area, unlike Stearns' proposal, included Sections 16, 21, 22, 25, 26, and 27 of T. 2 N., R. 34 E., around four thousand acres of the Pioneer Mountain foothills, of which the Little Cottonwood Creek watershed comprised twenty-three hundred acres. [4] As with the founding proclamation, this boundary adjustment passed quietly, the only point of controversy arising later, when the NPS attempted to construct an administrative water system.

THE 1930 PROCLAMATION: THE MISSING SPRING

Continuing its quest for water, the Park Service succeeded in having a proclamation signed on July 9, 1930 to add thirty-seven acres in Section 28 to the monument "that contains a spring which is needed to furnish the said monument with an adequate water supply." [5] Even though the spring was specifically mentioned in the proclamation, the legal description was incorrect. And the existing spring still lies outside the monument's northern boundary, part of a watershed the Park Service would seek to annex in several decades.

THE 1931 LAND EXCHANGE BILL

Although steps had been taken to secure a supply, transporting the water to the monument posed the biggest obstacle. To build the water system required more than annexing the northern unit, it also required running the water line over private lands. Thus, gaining right-of-way easement across the 320 acres of grazing lands owned by the Kilpatrick Brothers Company and the Arthur Brothers represented a critical element in the program. Without right-of-way permission, the Park Service would not commit to the completion of the water system, yet it was faced with the critical situation of watering the "dry" monument, a situation made all the more acute when funding was received in July 1930, mandating the system's completion within the year. [6] In the midst of this predicament, the agency also looked at the bigger picture. If it could obtain legislation to eliminate the private lands, it could avoid potential conflict with the system and damage to other resources. [7]

Under pressure of a deadline and with its eye on a larger goal, the Park Service negotiated successfully with only one of the land owners, the Kilpatrick Brothers, securing a right-of-way deed on October 10, 1930. [8] Able to cross only the Kilpatrick land, the Park Service thus pursued its ultimate objective of a land exchange. A preliminary stage in these negotiations occurred with the signing of a November 14, 1930 executive order that withdrew "public lands pending legislation," on behalf of the Kilpatrick Brothers. [9] To further assist the Park Service's development plans, Idaho Congressman Addison T. Smith introduced H. R. 15877 "to authorize exchanges of lands with owners of private land holdings within Craters of the Moon National Monument" on January 7, 1931. Essentially, the act enabled the Park Service to trade lands of equal value in the public range near the monument for those private tracts within it. Smith, unsuccessful with past legislation to develop the monument, was successful with this bill. [10]

The act met with strong agency support. Director Horace Albright backed the bill, stating in January 1931 that complete ownership of the 320 acres of private land, over which part of the pipe line would run, "would be very desirable from the administrative standpoint of the monument...." [11] It would allow the monument not only to control lands within its boundaries but also to better control the vital water supply. In seeking support for the bill, Albright expressed the importance that the Service placed upon the water system. We cannot "justify any...development," he said, "until we have the water supply and other conveniences of tourist accommodation." [12]

Albright also defeated a brief spate of protest by grazing interests. In January 1931, Thomas C. Stanford, president of the East Side Blaine County Grazing Association, attempted to block or amend the legislation to ensure continued grazing. In this regard, he complained of government mistreatment to both Representative Addison Smith and Senator John Thomas. Smith, by sponsoring the bill, remained on the agency's side. But Thomas, who had introduced the bill into the Senate on January 14, sided with the livestock industry and agreed to delay the bill. [13]

Stanford criticized the federal government's "exclusionary" policies at Craters of the Moon, pointing to the 1928 expansion and the prohibition of grazing in the monument. His understanding of the monument's creation was that the area would be small and withdrawn from only worthless lands; now, double its original size, it had removed valuable grasslands from the private sector. [14]

The rancher disparaged the Park Service for denying his group and others "the privilege to graze," and for hiding behind the excuse of the water system to steal range land from the livestock industry. Part of his protest stemmed from his confusion about the bill itself. He assumed, for instance, that new lands would be added to the monument, when this had already occurred, the only "addition" being the Service's control of private lands within existing boundaries.

Another point of confusion lay in the bill's provisions for reserving public land outside the monument's boundaries for the exchange, which exceeded the existing private holdings. Hence, Stanford worried as well that this was further encroachment on grazing interests. Sounding the traditional cry of Idaho's ranchers seeking unlimited and unregulated access to the public domain, a cry which reached a particularly high pitch during the depression, Stanford issued this warning. If "something is not done to curtail these inroads [sic] on our grazing lands, it will deal a death blow to our livestock industry." [15] In a February 12 letter to Senator Thomas, Albright tried to clear up the misunderstanding, stating that

not all of the public land described in the bill will be used in effecting this exchange. It was found necessary to include some alternate land in this description because of certain pending entries which may not make it possible to find land of sufficient value within this area to meet the value of the land proposed to be acquired in the monument. [16]

Learning of this allayed some of the senator's concerns, believing the director's assurances to work out a grazing compromise if the bill passed. For Stanford, this news reaffirmed his belief in the federal government's infringement on individual rights. He was somewhat embarrassed, however, to learn that his protests were interfering with the freedom of private land owners. He quickly clarified that he was concerned only with the removal of grazing restrictions on the land in question, or its removal from the Park Service jurisdiction altogether:

it was O.K. with our association for [the] Kilpatrick Bros. to make exchange of their private personal holdings, located in Crater zone, but...our association wanted protection against [the] Government including in said zone, ten sections of good grazing land, that had no scenic wonders, but was a great asset to Idaho, if used for grazing animals. [17]

Stanford's association withdrew opposition to the bill, Thomas allowed it to pass the Senate, and it was enacted on February 21, 1931. [18]

FINALIZING THE LAND EXCHANGE

During and after the water system's completion in June 1931, the Park Service negotiated the land exchanges contemplated prior to H.R. 15877's passage. There was a particular urgency in the agency's activities; first, the Kilpatrick Brothers were eager to complete the exchange, and second, the pipe line, apparently, crossed a small portion of the Arthur property, for which the Service possessed no right of way. [19]

Since the Kilpatrick Brothers were amenable to the Park Service's plans from the outset, negotiations proceeded with relative ease. The agency decided to trade the Kilpatrick's 240 acres within the monument for 400 acres outside it, the nearly two-for-one deal constituting an exchange of equal land values. The company's cooperation throughout the land negotiations also influenced this final settlement. It had granted the right of way, supported the bill, aided the exchange process, and suffered economic hardships since access to its lands was denied for years. [20] The exchange was completed on September 8, 1932, and officially accepted January 25, 1933. [21]

Negotiations for the Arthur lands, however, were not so simple. As it turned out, one of the Arthurs had died, and the estate was unable to grant an easement or sell the land. Between 1931 and 1933, the land issue then became mired in problems of land title over the eighty acres involved. The government, investigating the land's title history, discovered the legal owners, David F. and Ellen Coon, by 1932. The Coons apparently gained ownership of the tracts in January 1931 through a public auction after taxes went unpaid on the Arthur lands. When the government attempted to purchase the land, it was faced with a confusing set of circumstances. The Arthur estate fought the Coon's ownership rights in court, while at the same time trying to triple the estimated land value of $800 because of the land's importance to the monument's water system. To confuse the issue even more, John W. Smeed, a livestock owner who had obtained a mortgage to the Arthur property in December 1930, tried to purchase the land from the Coons for $400 and sell it to the government for double the amount and collect his investment. After delays and litigation, the Coons were awarded title by the courts on August 17, 1933, and on October 28, 1933 sold the Arthur lands directly to the government for $800; the land was officially accepted on November 6 of that year. [22]

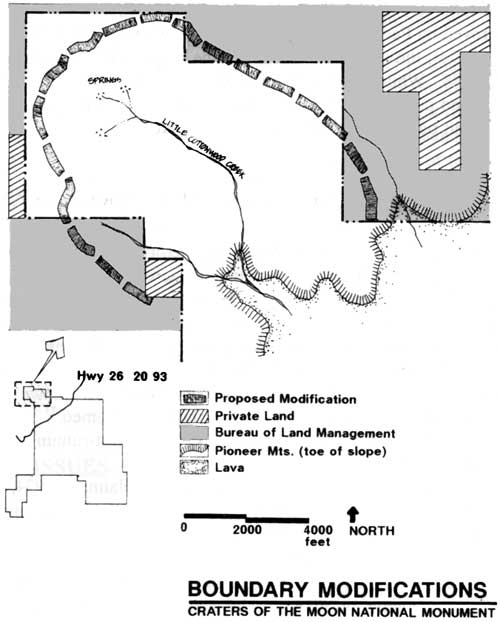

ADJUSTMENTS TO THE NORTHERN BOUNDARY

Attempts to protect the monument's watershed from livestock trespass and contamination, and its mule deer from hunters and poachers have frustrated managers from the time of establishment. The main point of contention is that the northern boundary does not run along the entire ridgeline of the Little Cottonwood drainage. Except for a small portion, the hydrographic divide does lie within the boundary. But the boundary line follows section lines rather than topographical lines, and posted or not, it has not been readily identifiable on hillsides. And for this reason, the boundary has been a source of confusion for sheepherders and hunters. Over the years, monument officials have proposed a number of solutions: enclose the entire divide within the monument, fence either the divide or the boundary, or realign the boundary along the ridge crest itself. [23]

The first step toward a resolution went forward with the 1936 act deleting most of Section 16. H. R. 7930, "to eliminate certain lands from the Craters of the Moon National Monument," attested to the administrative problems associated with the northern unit after the 1928 expansion. As had occurred with the establishment of the monument, boundaries were drawn without accurate knowledge of the region embraced by the park site. Mapping ensued after the fact, and new topographical surveys revealed that the northwest corner of the monument encompassed the slope of Lava Creek, an area north and below the ridgeline of the Little Cottonwood Creek drainage. In addition, this particular section functioned as a seasonal sheep passway. Lying outside the watershed and "zone" of "scenic" significance and inside the heart of range land, this tract was considered expendable.

In a sense, this legislation represented Thomas Standford's last stand. After the land exchange had been completed in 1933, Stanford, on behalf of his grazing association, filed a complaint with the Park Service contesting the validity of Sections 16, 21, and 22, seeking their removal from the monument. They were "of no scenic value and, consequently,...should have been left in the public domain." A General Land Office survey in September 1933 investigated the charges and agreed with Stanford's accusations that these sections were "not of scenic value." Yet the agent noted that they were not added for aesthetic reasons but "to protect the water supply." Therefore, only the northern three quarters of Section 16 should be excluded; "this portion...is not in the watershed." [24]

In 1934, taking all of this into account, the Park Service requested that Congress delete 463 acres from Section 16--approximately two miles of boundary. In doing so, Craters of the Moon would better protect its water supply, gain "a more natural boundary," eliminate the need for difficult boundary patrols, and help to "facilitate the administration thereof in connection with the grazing problem." On April 16 of that year, Congressman Rene L. DeRouen introduced the bill and, while uncontested, it was not passed until June 5, 1936. [25]

While this legislation only solved part of the problem with trespass grazing and hunting, no concerted efforts to rectify the situation occurred until mid-century. Worried about water quality and growing volumes of visitors, the Mission 66 prospectus recommended acquiring the entire Little Cottonwood watershed. The only part of it not protected was the west fork of Little Cottonwood Creek, located in Section 28, of which the monument possessed the upper northeast corner. BLM and private grazing lands extended down from the ridgeline to monument land, causing sheep and hunter trespass to happen easily and often.

In a January 4, 1963 boundary report, Superintendent Daniel E. Davis stated that for "all practical purposes" the northern boundary was on or near the divide and easy to define, except for Section 28. To correct this, he recommended altering the boundary to follow the ridge, thus making it "much easier to protect the Monument's wildlife and water resources from encroachment by hunters and livestock." The revision would involve 120 acres, an exchange of 80 BLM acres and 40 acres of private land. At the time, the present land owner also held a grazing permit to the remaining BLM lands, yet posed no immediate threat to monument resources since he willingly avoided trespass by neither using the grass nor water on this section of land. [26]

Anticipating that this amicable situation would not last forever, Superintendent Roger Contor continued negotiations. Contor, however, reported a snag on February 10, 1965. While the land owner, Ed Bowman, was willing to cooperate, he wanted to exchange rather than sell his land in order to maintain his grazing acreage; the extension would have deleted his own land and robbed him of the adjacent land leased from the BLM. Like Bowman, the BLM was willing to assist, but could not offer any adjoining lands to create the exchange. Since the decision had been made to acquire the private lands through purchase and the public lands through proclamation, Contor and his staff arrived at two solutions.

The first plan was to purchase an equal amount of land in Section 20 (if possible) through the monument's natural history association, trade this for Bowman's holdings, and add his BLM grazing lands to the monument. Under these conditions, the livestock owner would duplicate his present situation, and the Park Service would gain around 170 acres and the watershed but not the hydrographic boundary. The new boundary, though, would provide adequate protection, forming a triangle in the northeast corner of Section 28. The second plan proposed redrawing the entire northern boundary along the hydrographic divide. This revision entailed releasing approximately 460 acres of monument land in Sections 16, 21, and 22 "for exchange and grazing under BLM administration." With these lands available, the Park Service could satisfy Bowman's needs and meet its own. [27]

Of the two, Contor preferred the first recommendation. He was not a firm believer in a hydrographic boundary. The grassy ridges of the Little Cottonwood area offered no deterrence to hunters tempted by deer in the watershed and no defense against sheep "spilling over into forbidden territory where the grass is much superior." Hence, this type of boundary promised more not less trespasses, while a properly marked "hillside" boundary would stop both honest hunters and sheepherders. In either respect, action was necessary, by an act of Congress if nothing else. [28]

Despite these efforts, the boundary revision proposals fell by the wayside but anticipated future management actions. In the absence of boundary adjustments, the situation became mired in management conundrums. In the mid-1960s, monument managers toyed with the idea of fencing the watershed to protect it against livestock contamination and grazing. The puzzling question was where to locate the fence. The BLM suggested fencing the ridgeline as the best practical way to protect the watershed. A fence along the "hillsides" would impede livestock grazing and would be destroyed by winter snow drifts. The BLM proposed, then, that the Park Service build the fence and lease "insignificant" lands outside of the drainage for grazing. [29] While the proposition might solve one problem, it would create others. Grazing was anathema to Park Service management, and ridge-top fencing would unofficially eliminate park lands.

Under increasing grazing pressures in the late 1970s and 1980s, the Park Service, however, undertook two fencing projects on its northeastern boundary along the hydrographic divide. In doing so, it allowed grazing under a special-use permit for around 150 acres of land "fenced out" of the monument. But by the late 1980s, this situation changed; federal regulations revoked the special-use permit, placing the monument in the unrealistic position of prohibiting grazing in this section. Similarly, the monument was faced with grazing threats from livestock operations on its northwestern boundary. Earlier fears of uncooperative graziers had come to haunt the administration.

In 1986 Superintendent Robert E. Scott, deeming that the monument had exhausted its options, submitted a proposal to amend the northern boundary, placing it along the hydrographic divide and fencing it. Similar to Contor's 1965 proposal, Scott's would accomplish the same goals; it called for a land exchange with the Bureau of Land Management, adding 210 acres and deleting 315 around the northern sections. Motivated by livestock trespass, the proposal was presented as the best solution after decades of conflict. Although illegal hunting might increase it was manageable by comparison. For this proposal "will protect the quality of the Monument's water supply and create a more manageable boundary for both the National Park Service and the Bureau of Land Management." [30]

Approved by Pacific Northwest Regional Director Charles Odegaard and the Washington office, the proposal was sent to the Department of the Interior on January 20, 1988. While the document received the approval of the agencies, private land owners, and politicians involved, it joined the larger issues of water rights adjudication and park designation. Until these issues are solved, the proposal remains on hold. [31]

|

THE LAST OF THE PRIVATE LAND: THE MARTIN MINE

Adjacent to the Lava Creek Mining District, the monument's northern unit still contained ten known mining claims, totaling 180 acres, after the 1928 expansion. As part of the land exchange program of the 1930s, the Park Service attempted to eradicate these claims and obtain ownership to all lands within the monument. [32] Nine of the claims formed the Martin Mine, or Creek Lode mining claims, covering approximately 160 acres in Section 22. The last claim, was about twenty acres in Section 22, and, while its validity remained in question for more than a decade, its title was eventually cleared and federal ownership was assumed. [33] The Martin Mine, however, was a different story and proved to be the longest-running mining claim case at the monument.

The Park Service had a chance to purchase the claims in 1934, when the mine owners, Otto Fleischer and Era L. Martin, [34] offered to sell their claims for $4,000 and later $5,000. But the agency considered this price too high, and believed that with time and the deepening depression the asking amount would downturn. That was not the case. The mine, under various owners and names, operated intermittently and apparently just enough to maintain the claims for the next thirty years. [35]

In the meantime, the Park Service eliminated a large number of past mining sites and claims with the 1936 boundary revision. The agency renewed its interest in settling the Martin claims after World War II but was unsuccessful until Mission 66. [36] B.F. Manbey, Regional Chief of Lands, stated on September 29, 1959 that taking a more aggressive position in acquiring the mining property was wise, considering that "the recent extensive developments in the Monument are more likely to draw special attention to these claims and possibly influence others to try to obtain them before we can take action ourselves." [37] Negotiations faltered with the question of worth. Mrs. Francisco, wanted $15,000 for the property in 1959. The Park Service considered the asking price not only because of recent monument developments, but also because the owner was elderly and willing to sell to the Park Service. It was also possible that, if the mine contained valuable ore, a large mining company could buy the property and imperil monument resources. [38]

Although the director of the Park Service favored buying the lands, no immediate funding existed for such an acquisition. Instead Superintendent Floyd Henderson, who was active in the negotiations, pursued a settlement through property appraisal. [39] In his October 11, 1960 report, Bureau of Land Management mining geologist Quin A. Blackburn dismantled the validity of all but one of the nine claims, the Creek Claim. In the fall of 1961, the BLM declared three of the nine claims null and void; and an August 4, 1964 decision declared five more claims invalid. The final Creek Claim of 20.66 acres was contested because the asking price had escalated to the "ridiculous" sum of $50,000 when the property was valued at $1,000, the Park Service's offer. Although the asking price was lowered to $5,000, the amount was still too high, and the BLM scheduled a validity hearing for August 1966. However, the parties involved waived the hearing and settled out of court for the Service's proposal. The Craters of the Moon Natural History Association purchased the property and relinquished the claim on January 17, 1967, and donated the mining interests and land to the National Park Service the following month, thus freeing the monument of all private inholdings. [40]

OTHER LAND ISSUES

THE 1941 PROCLAMATION AND MONUMENT HIGHWAY

In 1938 two organizations, the Eastern Idaho Association of Civic Clubs and Southern Idaho Inc., formed to promote the development of eastern and southern Idaho. Influenced by the depression, these activists saw tourism as an answer to their region's economic problems and campaigned for road improvements on Highway 22, the route connecting Shoshone and Arco. They were drawn to this particular stretch of highway since it traversed Craters of the Moon National Monument. With proper improvements (oiling and grading), the highway would create an east-west flow of traffic through southcentral Idaho; Craters of the Moon, by now receiving nearly twenty thousand visitors a year, would provide the incentive--a roadside attraction for tourists visiting Sun Valley and proceeding to Yellowstone National Park. [41]

Custodian Guy E. McCarty supported the highway improvement campaign and requested that the Park Service upgrade the monument's section of highway. Another reason to assist occurred in 1940 when the state of Idaho began improving Highway 22, realigning and shortening the road from Arco to the monument. To do this the state relied on federal funds, which could not be used in national parks. If the state chose to fund the construction through the monument, it would deplete its budget and have to postpone the improvement of the last stretch of highway to Arco. Interested in helping, the Park Service stated that it could not expend any funds for highway improvement; the road was neither constructed nor maintained by the Service, but rather by the state itself. In fact, the proclamations of 1924 and 1928 had eliminated most of the right-of-way of the state highway from the monument. After consultation with the state of Idaho and the Public Roads Administration, the Park Service decided that a new proclamation should be drafted ceding the entire right-of-way to the state, and making the road eligible for improvement under the Federal Aid Highway program. [42]

Signed on July 18, 1941, a presidential proclamation transferred a strip of approximately ninety-four acres to the state of Idaho. The legislation excluded the land from the monument and removed it from Park Service jurisdiction. It resolved the issue at the time, but meant that the agency would have little control over that section of the monument. [43]

THE 1952 SCHOOL LANDS CONDEMNATION

In 1952 the Park Service brought to a close negotiations for the acquisition of two tracts of state owned school lands containing some eight hundred acres within the monument. The lands were included within the area's boundaries as a result of the 1924 and 1928 proclamations, and constituted the largest acreage of nonfederal lands within the monument--approximately 1,260 located in Sections 16 and 36.

Director Horace Albright expressed interest in acquiring the school lands in the early 1930s during proceedings for the water system development. However, it was discovered that Idaho law prohibited the exchange of school grant land, thus negating congressional legislation or executive orders employed in the water system land negotiations. [44]

Then in 1948 the Idaho State Land Board declared its interest in eliminating the state's land holdings within the monument. The Park Service, though, needed to find a method of purchase other than exchange. Direct purchase was out of the question, since Idaho law stipulated that school lands could be bought for no less than $10 an acre, a price too high for the Service. After several years of legal investigation, the Park Service followed the precedent set by the Atomic Energy Commission during its development in August 1950, and entered into condemnation investigations the following October. The Land Board supported this means of acquisition. In May 1951 an appraisal of the lands was conducted, and a price of $2,880 set; it was acceptable to both the Park Service and the state of Idaho, after some minor conditions were ironed out. [45] A February 13, 1952 preliminary condemnation hearing formalized the acquisition, and shortly thereafter a check was issued and the case closed. [46]

THE 1962 PROCLAMATION AND CAREY KIPUKA ADDITION

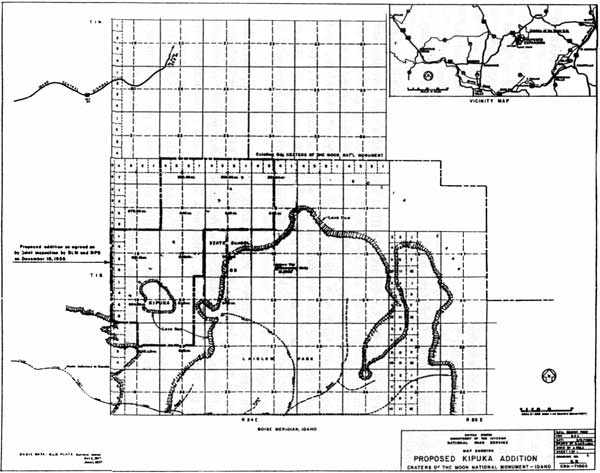

As part of its mission to preserve features unique to a volcanic environment and of scientific importance, the monument added a kipuka, a small island of relatively pristine grassland surrounded by more recent lava flows, in 1962. Range scientists discovered the Carey Kipuka in the mid-1950s; it lay about four miles southwest of the monument's southwestern corner, on Bureau of Land Management land.

The idea for the addition grew out of a 1956 study conducted by Dr. F. R. Fosberg, from the National Academy of Sciences, and Dr. E. W. Tisdale, an ecologist from the University of Idaho. Both men believed that the island of grass deserved protection as part of Craters of the Moon National Monument because it was of great scientific value for "the study of grassland ecology." In southern Idaho, "undisturbed areas showing the climatic vegetation climax of grasslands" were fast becoming rare due to grazing and agriculture. The kipuka's "present pristine condition" was the result of a surrounding expanse of rough lava, which had rendered the area inaccessible to domestic livestock. Furthermore, there was little incentive to graze here since ample vegetation existed outside the lava buffer, and there was a shortage of water within it. [47]

On June 26, 1958, Fosberg, representing the Nature Conservancy, submitted his and Tisdale's report on the kipuka to the director of the National Park Service, requesting that the agency annex the kipuka to the monument. The report stated three reasons for the addition:

1. The kipuka contains mature soils and vegetation such as do not occur in the present monument area and which are not found commonly elsewhere in the region due to grazing pressure.

2. While the area is protected from normal grazing by the raw lava flows, it could be made accessible to livestock and at present there is no legal restriction to prevent the area from being used.

3. The area between the kipuka and the national monument consists mainly of raw lava with little or no grazing value. It should be possible to connect the area without withdrawing any appreciable amount of grazing land. [48]

While range scientists admitted that "possible" disturbance had taken place at the kipuka through wildlife and Native American use, the comparative qualities for range studies were invaluable, the extent to which would only be realized if the area were set aside as park land. [49]

Park Service Director Conrad L. Wirth gave his blessing to the proposal and ordered an agency investigation. On September 3, 1958, Superintendent Floyd Henderson and Grand Teton National Park Biologist Dr. Adolph Murie conducted the initial investigation. [50] In their joint report of October 17, 1959 Murie and Henderson confirmed Fosberg and Tisdale's findings, and recommended the kipuka's addition to the monument. They noted that it was a rare opportunity to preserve unmodified grasslands (and mature soils) in the grazing regions of the Snake River Plain. The investigators suggested adding 7,583 acres, contiguous to the monument, in order to shelter the grass island by a natural barrier of raw lava formations. Of that land only four hundred acres, exclusive of the kipuka proper, contained grasslands--marginal at best--which could possibly cause conflict with grazing interests. The kipuka, moreover, merited addition because of its importance to the monument's purpose; it was "wholly scientific." It possessed "no outstanding scenic, or known prehistoric or historic features, and no direct interpretation or the ordinary kind of recreation possibilities." In fact, its inaccessibility was its best attribute, being the reason for its undisturbed state and ecological value. All of this posed no administrative costs or burdens. But the clock was running and it was only a matter of time until this grassland was engulfed by grazing or other uses under current BLM management. Its protection could not be guaranteed, and Park Service acquisition was imperative. [51]

Based on the team's preliminary reports of September 1958 and February 1959, Region Four Director Lawrence Merriam approved the proposal and transmitted the recommendation to the director on February 19, 1959. Acting Director Eivind T. Scoyen's response was favorable, but with some qualifications. First, he advised that a smaller, detached unit would provide adequate protection and, it seems, avoid protests from livestock owners. Second, and along these same lines, he suggested that the agency consider allowing current grazing--what little there was outside the kipuka--to continue. [52]

Initially, it appeared that none of this would matter. In October 1954, the Air Force had reserved a large tract of land south of the monument to use in an "air-to-air gunnery range" in which the kipuka addition lay. Public Land Order No. 1921, however, revoked the withdrawal in July 1959, and the lands were again open to application. On November 5 Acting Regional Director Herbert Maier renewed the kipuka proposal, and reflecting Scoyen's remarks, recommended a detached unit comprised of approximately forty-three hundred acres, whereby grazing, if necessary, would be granted under special permit outside the kipuka proper. [53]

In order to guarantee withdrawal, however, the Park Service faced the grazing issue again. In December the Service and the BLM conducted a joint investigation "to determine the impact the proposed withdrawal might have upon the grazing use of the land by permittee." In their January 26, 1960 report, both agencies arrived at the final proposal by excluding any lands "suitable or available for grazing." With only lands of "no conceivable economic value whatsoever," and which also happened to be ecologically significant, it was now possible to make the addition contiguous with the monument. And finally, this resolved the addition's size, 5,361.41, an increase of about a thousand acres. [54]

Although Assistant Secretary of Public Lands, Roger C. Earnst approved the kipuka proposal on July 5, 1960, the legislative wheels spun for two years. Public support was not the problem. Throughout the recommendation process, conservation groups such as the Nature Conservancy, Wilderness Society, and Ecological Society of America, as well as local, state, and federal agencies expressed their support of the addition. [55] Bureaucratic delays, instead, were to blame.

The addition traveled a circuitous legislative route, from a proclamation to a bill and back to a proclamation. It was submitted too late for presidential approval by the end of term in January 1961. Afterwards, the Park Service decided to pursue congressional action, since more than five thousand acres of public domain were involved and would require congressional approval. [56]

Idaho Senator Frank Church volunteered to sponsor legislation on May 22, 1961. Yet more delays ensued after Church and his staff questioned the grazing issue, anticipating opposition from the state's powerful lobby. They also questioned the merit of the addition itself. Why should an inaccessible area be protected? What would be advantageous about adding the kipuka to the monument? Moreover, they wondered about the addition's main purpose--enclosing an area of public land for "wholly scientific" reasons. This logic, so it seemed, ran counter to the Park Service mission of preservation and use; scientific research as a primary objective would obviate visitor use and enjoyment. [57]

Having considered these questions already, the Park Service was able to satisfy the senator's concerns. Yet Church's queries revealed some misconceptions about the addition. Phrases like an "impenetrable barrier" of rough lava encircling the grassland, for example, caused the kipuka to appear indestructible and not worthy of park protection, but these descriptions helped explain the site's "pristine" state. Furthermore, the narrow focus of the kipuka as a "natural laboratory" stressed the site's primary importance but ran counter to the Service's traditional focus of visitor development and education. After this interchange, the agency revised its justification somewhat, underscoring the kipuka's scientific importance due to its isolation, but also emphasizing how its addition would "greatly enhance the interpretive and preservation objectives of the monument." [58]

Convinced of the bill's merits, Senator Church introduced the kipuka addition as S. Bill 2573 on September 12, 1961. [59] The bill, "to add certain lands" to Craters of the Moon National Monument, sailed through the Senate, House, and Bureau of the Budget unopposed. By July 1962, though, the Senate Subcommittee on Public Lands "informally" advised the Department of the Interior that the legislative authority of the Antiquities Act was the best means to acquire the kipuka. Justification for the addition reflected the purpose of the 1906 act; it was an area of scientific, ecological, and educational significance and value. Coming full circle, the Park Service took this course, and Proclamation 3506 was signed by President John F. Kennedy on November 19, 1962. [60]

|

| This map shows the 1959 kipuka addition proposal; note the trails leading to the kipuka and the lava barriers thought to shield the area from animal and human contact. |

WILDERNESS ESTABLISHMENT

Sit sometime in the middle of the Black Flow of Craters of the Moon. Though only three miles from a paved road, you will be a half day's journey into the wilderness. And a century into the past. The mood is unmistakably wild and remote. It is like being in a motionless black ocean. [61]

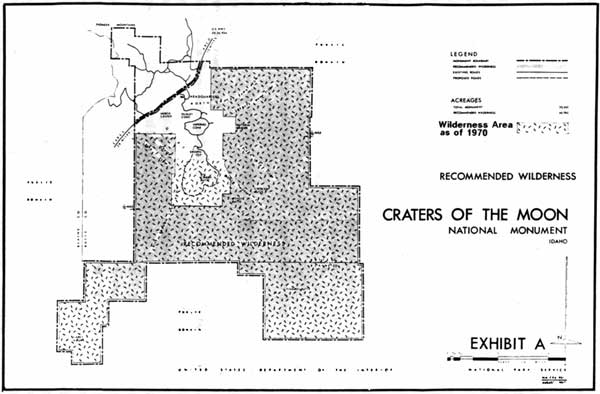

The passage of the Wilderness Act on September 3, 1964 mandated that all National Park Service sites with five thousand or more contiguous roadless acres be studied for possible inclusion in the National Wilderness Preservation System. The act stipulated a ten-year review period; Craters of the Moon's study was begun and completed in 1965, and its wilderness established in 1970. The first Pacific Northwest Region park unit to be designated as wilderness, the monument, along with Petrified Forest National Park, was the also the first NPS unit to be granted the status by Congress. Relatively "issue" free in the public sector, the creation of the area's wilderness caused some internal conflicts within the Park Service itself. Because of this and the honor of being "first," the wilderness area's establishment deserves special attention.

In May 1965, Superintendent Roger Contor, joined by a small master plan team, studied a 42,600-acre roadless area in the monument for wilderness classification. The group completed the study in ten days, and their preliminary proposal determined that 41,475 acres were suitable for wilderness; after the Washington office reviewed the proposal, it decreased the acreage to 40,800, altering boundaries to conform with survey points rather than natural features. The proposed volcanic wilderness comprised approximately 80 percent of the monument's land base, and 96 percent of the area studied. All of it lay south of U.S. Highway 20-26-93A, excluding the semi-developed zone of roads, trails, and administrative facilities in the monument's northwestern corner. To name the area, Contor chose a Shoshoni term, Tu'Timbaba, or "Black Rock Overpass," referring to the thousand feet the lava landscape rises above adjacent valleys. [62]

Justifying the reasons for wilderness classification, the superintendent wrote of the area's unique qualities; it offered

geologic curiosities, archeological structures and sites, a surprisingly rich fauna, and vegetative cover of special importance to science. The setting is fresh and clean. Because access is limited to hikers, and because there are no attractions which lack counterparts in the more accessible parts of the Monument, human use has been scant.

This was, he recognized, not what people pictured as traditional wilderness; there was "nothing here to attract the mountaineer, a thirty day pack trip party, or a fisherman." Yet Contor believed that the area's "appreciation must rest on other things." It "remains the most interesting and least disturbed segment of the entire Snake River Plain. Those who spend time here will soon feel its lonely and unusual charm." [63]

Following the wilderness proposal was a public hearing, as required by the Wilderness Act. Held on September 19, 1966 at Arco, Idaho, the meeting itself was rather sedate; fifteen people attended, among them Park Service and conservation group representatives. Five of these individuals gave oral statements, and a total of forty-eight letters were received from private parties, local, state, and federal agencies. In general, everyone favored the agency's wilderness proposal. No one, for instance, objected to the concept of wilderness; like Contor they expressed an affinity for the area's qualities of beauty, science, and isolation. Nor did anyone urge a reduction in the proposed area's size. Rather, those few who did criticize the proposal wanted more land added to the wilderness area. [64]

Groups such as the Sierra Club, the Federation of Western Outdoor Clubs, the National Parks Association, the Mountaineers, and the Wilderness Society suggested inward expansion, pressing closure to the developed area of the monument. On the high end of the scale, the National Parks Association proposed four separate wilderness areas south of the highway, totaling 49,800 acres, excluding the headquarters facilities and road corridors. And on the low end of the scale, the Wilderness Society recommended a small boundary adjustment to include the Caves and Natural Bridge. While the different proposals varied on size, they shared a common trait in that they did not contest the planned road extension around Big Cinder Butte. [65]

In defending its proposal, the Park Service explained that it designed the wilderness boundaries to retain access to the volcanic features along the loop drive, and to provide a half to a mile wide buffer to avoid the "influences from U.S. Highway 20-26-93A and the existing and proposed visitor use areas southeast of the highway." By way of compromise, the agency's August 1967 proposal offered a series of revisions to the original boundaries. On the one hand, reflecting some but not all suggestions, the adjustments added a total of 1,945 acres. These extended the proposed boundary to embrace the Natural Bridge and more portions of the North Crater Lava and Serrate Lava Flows; the Black Lava Flow, Coyote and Crescent Buttes, and additional sections of the Big Crater and Blue Dragon Lava Flows. On the other hand, two deletions of 1,960 acres comprised more acreage than did the additions. One subtracted a small amount, eighty acres, southwest of Inferno Cone; the other removed a large amount to provide a sixteenth of a mile administrative buffer between wilderness and monument boundary. [66]

The 1967 proposal satisfied most public concerns for including key sites in the monument's internal section, as well as the administrative practicality of drawing boundaries along easily distinguished grid patterns, as opposed to the diagonal shapes of the original recommendation. In total acreage, 40,785, the latest proposal differed little from its earlier version.

As for other additions, the Park Service denied these for pragmatic as well as development reasons. Most features proposed for wilderness addition, for instance, were located along or near the loop drive and trails, and were among the monument's primary attractions. Here the majority of the monument's 200,000 annual visitors experienced the outstanding geologic features. Thus, to those proposals requesting that areas west of the Natural Bridge and Caves be classified as wilderness, the Park Service stated that anticipated visitor volumes would require "highly developed trails...[the] minimum...sanitary facilities, and interpretive devices," for visitor health and safety as well as the "protection of natural features." Similarly, proposals that singled out Inferno Cone and Big Cinder Butte for wilderness protection were characterized by the Service as small islands, 270 and one thousand acres respectively, within the existing road system and its proposed additions. As "major visitor attractions" they should remain outside wilderness; their small size meant that they could not "offer significant or outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation as would be characteristic of a wilderness." [67]

In terms of wilderness designation, Big Cinder Butte assumed an important role. Because the monument's visitation and administrative infrastructure were confined to the northwestern corner, the Park Service believed that future growth would need outlets, and as shown in the 1966 master plan, the Service planned to extend the road system around Big Cinder Butte. [68] As Roger Contor noted, his master plan and wilderness proposal omitted the butte for future possibilities; "putting everything in wilderness would tie the hands of future managers. We felt we should leave the option open for some limited expansion of frontcountry facilities." At some point, windshield tourists might enjoy a new perspective on monument landscapes. Excluding Big Cinder Butte from wilderness, then, "gave a little elbow room," and, as Contor asserted, "a modicum of roadside scenery might reduce their [visitors'] passion for self entertainment through vandalism or other unacceptable behavior." More importantly, perhaps, was that he was dealing with "firsts." Better to add than to subtract from wilderness, and refrain from setting a bad Park Service precedent should expansion be necessary. For that matter, it was never certain that the road would be built. [69] Even so, this belief later provided a point of internal contention.

Legislation for the monument's wilderness commenced the following year. In March 29, 1968, the Department of the Interior submitted draft legislation to the president for the creation of the Craters of the Moon wilderness, and sent the same material to Idaho Senator Frank Church, member of the Senate Interior Committee, seeking his sponsorship. [70] One year later, April 1, 1969, Church introduced the Department of the Interior (NPS) proposal as S. Bill 1732. In his oration to the Senate, Church justified the legislation by describing the monument's astonishing moon-like beauty, a beauty with relevance to the nation. That same year astronauts planned to walk on a similar lunar landscape, and for this reason, wilderness designation was appropriate. And it was all the more imperative since the drawing power of this national event would lure thousands more tourists to the monument and jeopardize its wilderness quality. [71] On June 15, the bill passed the Senate.

The bill followed a different path in the House. On March 3, 1970, it was introduced and referred to the Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, where it died. A month later, Idaho Congressmen Orval Hansen and James McClure introduced two wilderness bills, H.R. 16821, which was the NPS administrative proposal, and H.R. 16822, which called for the addition of more lands including Big Cinder Butte, for a total of 43,243 acres. [72]

The latter legislation represented the influence of Superintendent Paul Fritz. Fritz, who succeeded Contor in the fall of 1966, disagreed with the accepted master plan and wilderness proposal. In particular, Fritz believed after walking the proposed boundary that the planned road addition encircling Big Cinder Butte was a mistake. [73]

The main attraction of the new road was the tree molds of Trench Mortar Flat, the only features not accessible by car. While this extension would complete the motorist tour of the monument, preservation of these fragile lava formations outweighed the importance of visitor access. In a December 10, 1966 memorandum Fritz requested a new master plan study to enlarge the wilderness boundary to include Big Cinder Butte and prevent further development. Assistant Director of Cooperative Activities, Theodor R. Swem, rejected the superintendent's proposition. No reason warranted revision of the recent master plan; it had been agreed to at all levels of the administration. And more importantly, "the plan provides a reasonable balance between wilderness and non-wilderness use and it also provides opportunities for increased and improved interpretation of the area." He urged Regional Director John Rutter to bear this in mind in order to "overcome the difficulties" posed by Fritz's suggestion. After learning that his superiors would not entertain any boundary changes, the superintendent reluctantly agreed to the agency's proposal. [74]

Despite his original agreement, Fritz countered the Service's plans by circumventing administrative channels to win approval of his wilderness proposal. Beginning in 1967, he gained support from local communities and environmental groups, such as the Sierra Club and Wilderness Society, who had originally expressed their desire to add more lands to the Craters of the Moon wilderness. These interest groups then lobbied the Park Service and congressional representatives, and in Congressmen Hansen and McClure found sponsors for the new proposal. [75]

The Park Service in spite of Fritz's influence stood behind its original proposal passed by the Senate. Acting Secretary of the Interior Fred J. Russell expressed the Service's position to Congressman Wayne N. Aspinall, chairman House Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs, in a June 25, 1970 letter. In principle, the Park Service determined that development was necessary to meet the monument's mission and to accommodate rising visitation. The road encircling the butte

would disperse visitors to relieve congestion on the present road system; such congestion is expected to become critical in future years. Exhibits along the road would interpret such features as tree molds, lava tubes, fissures, ecology and plant succession. Visitors unable to make long hiking trips would have access to all of the major types of volcanic features on this self-guiding interpretive road.

Hence, wilderness designation for Big Cinder Butte would preclude both this improvement and the presentation of the monument's full array of volcanic phenomena to the motoring public. [76]

Unfortunate for the Service and fortunate for Fritz and supporters of the Big Cinder Butte addition, the House Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs concluded in their favor. H.R. 19007, an omnibus wilderness bill introduced on August 13, 1970, provided for an enlarged Craters of the Moon wilderness of 43,243 acres. [77] Commenting on the amended bill in a September 9 report, the committee stated that the addition of "this 2,243 acres of land would make a meaningful contribution to the wilderness area and that it would not unduly interfere with public use and enjoyment of the national monument." [78] The full House passed the bill on September 21, 1970. The Senate concurred with the House in S. 3014 on October 12, and President Richard M. Nixon signed the bill into law on October 23, 1970. [79]

In the end, the Park Service lost with its proposal, but won by gaining the first wilderness in the System. Compared to the larger parks, the Craters of the Moon proposal lacked high-profile controversy, and buried in a large bill, the discrepancy over two thousand acres lost some of its importance. The new Craters of the Moon Wilderness, as it was called, [80] bore the stamp of Superintendent Paul Fritz, who spoke out against his own agency for the protection of monument resources. Yet the area also owed its existence to individuals, such as Roger Contor, who recognized the volcanic environment's wilderness caliber.

|

| The 1967 wilderness proposal. The lighter screen-tone represents the Big Cinder Butte addition that was attached to the final bill in 1970. |

PARK VERSUS MONUMENT: A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

The creation of Craters of the Moon as a national monument rather than a national park is a theme that has relevance throughout the area's history. Changing the status from monument to park has arisen several times since Craters of the Moon's designation, raising the question of standards and what defines a national park. Traditionally, parks preserved only the most sublime tracts of the western landscape. Parks were large natural areas, diverse, panoramic, and pristine. They were the best of the best: the "crown jewels" of Yellowstone, Yosemite, and Glacier. [81] Whether Craters fit into this category has been the subject of some debate. Monuments by virtue of the Antiquities Act were to protect specific natural and cultural sites of scientific and historical value within a small area. How the monument rated in beauty, natural diversity, and size has formed important elements of the discussion, not just as a matter of principle, but because many equate park status with increased tourism and national recognition. For these reasons, Idaho residents have periodically lobbied for redesignation of Craters of the Moon as a national park.

That monuments could become parks grew out of the expansion of the National Park System. When adding new parks, the Service inconsistently adhered to its espoused standards and opened the door for exceptions. Interpretation of the Antiquities Act, with its broad language, led to a wide range monument types and sizes in the early 20th century, blurring the distinction between monument and park classification. This occurred because the creation of parks was subject to the will of Congress and often met with congressional delays. The 1906 legislation, on the other hand, bestowed upon the president the power to establish monuments, bypassing lengthy and costly political battles. The Park Service's two energetic and resourceful leaders, Stephen T. Mather and Horace M. Albright, often employed the monument category as a storehouse for threatened lands meeting political opposition as national parks. Grand Canyon, Zion, and Acadia national parks, for example, began as national monuments; once political conditions were favorable, they were upgraded to national parks. Application of the monument designation in this manner clouded classification standards and how the Park Service viewed the role and value of monuments in general. [82]

Most of the parklands created from monuments were "parks-in-waiting." Characterized by spectacular scenery and size, they overshadowed a conglomeration of smaller areas presenting an archaeological, historical, or geological theme. When these elite sites were gone, the remaining monuments were relegated to a "second-class" distinction; administratively, they suffered from inadequate funding and neglect. Focused on collecting more jewels for the park crown, the Park Service overlooked the needs of monuments in the process. The federal reorganization of 1933 consolidated the administration of national monuments under one agency, the Department of the Interior, for the first time, granting them better management and a higher station. Even so, the past was hard to shake. And the popular view throughout Park Service history, it seems, is that park status confers more prestige and importance on an area. [83]

The limited historical documentation surrounding its designation suggests that Craters of the Moon did not experience the monument-park type of tactical maneuvering. There is no evidence that the monument's establishment was embroiled in controversy. The government carved the area's boundaries out of a remote, uncharted section of the public domain deemed economically worthless. Moreover, the area's characteristics fell within the guidelines of the Antiquities Act. The volcanic phenomena were compressed within a small geographic range. Simply put, Craters of the Moon was a monument to geology.

There never seems to have been any question about Craters of the Moon's distinction from the start. Early resolutions, for example, emphasized setting the site aside as a monument. Director Stephen Mather concurred when he discussed the area's merits in terms of how well they matched the Antiquities Act's provisions for scientific values. Congressman Addison T. Smith, who thought highly of the area, favored monument over park status as a political expedient. Furthermore, as the activities of men like Robert Limbert attest, protection was more important than classification.

Yet the monument was not entirely free of discussion over park status. In the four years after the monument's designation, talk surfaced about the possibility of upgrading the area to a national park. The seeds of reclassification had been planted in the creation era when some supporters had pictured an area measuring 250 square miles. Not surprisingly, when news of the 1925 and 1926 surveys and expansion plans surfaced, Arco residents grew excited hoping that the monument's enlargement would lead to its conversion into a park. In October 1926, the Advertiser noted that Stearns had discovered new and extensive features, such as tree molds and caves, adding greatly to the monument's significance. To protect these discoveries, the monument might be enlarged by as much as one hundred square miles. These new developments, the paper concluded, made "the monument of such importance that he [Stearns] will recommend that the Monument be made a National Park." [84] Reclassification would bring increased Park Service attention in the form of appropriations, maintenance, and administration. Primarily, though, it would bring increased importance and recognition to the region.

Harold Stearns' enlargement report of March 1927, however, contained no recommendations for altering the monument's classification. One last attempt occurred in December 1927. Addison Smith proposed "to introduce a measure in congress [sic] at the present session to have this change take place." [85] Despite this announcement, no legislation entered the federal record, and when the monument's size was increased in 1928, its classification remained the same. Presumably, the same reasons which applied in 1924 carried weight four years later.

Although Craters of the Moon received little opposition, addressed either as a monument or as a park, the national park idea was not cast about casually in Idaho. Idaho is the only western state without a national park. Reasons for this can be seen in the near century-long debates over the Sawtooth national park proposals. They evince the strength of the state's powerful mining, timber, and grazing lobbies to oppose any infringement on resources perceived to be exploitable. Hardly the rival of the Sawtooths in scenery or resources, Craters of the Moon has nevertheless been the focus of discussion for Idaho's first national park. Within the last two decades, the debate over national park classification has resurfaced, raising many of the same issues discussed in the 1920s.

RECENT PARK MOVEMENT

In 1969, Craters of the Moon Superintendent Paul Fritz rekindled the proposal for the monument's expansion and national park status. [86] Fritz was spurred by the research of volcanologist Dr. Fred Bullard in the mid-1960s, who asserted that the lava flows surrounding the monument contained "the entire story of vulcanism...with only an active volcano missing." Further influencing his vision was the 1969 NASA astronauts' one-day training mission at the monument. Accompanying the astronauts as they familiarized themselves with a lunar landscape, Fritz realized for the first time the importance of "what was out there beyond the monument." [87]

What lay out there was the rest of the Great Rift, and Fritz proposed that the new national park include the three major lava flows along the Rift's sixty mile length: the rest of the Craters of the Moon Lava Field virtually surrounding the monument, and as separate units to the south, the Wapi and Kings Bowl flows. Within this landscape existed features already common to the monument, yet there were some standouts; the Kings Bowl contained, for example, the 155-foot-deep Crystal Ice Cave and the world's deepest accessible rift of eight hundred feet. The superintendent also envisioned drawing boundaries around Cedar Butte and Big Southern Butte, the 7,500-foot dormant volcano southeast of the monument. Besides expanding to include the flows of the Great Rift and associated features, Fritz's proposal contained practical matters. It would have acquired approximately forty acres of the only private land left adjacent to the monument's northwestern boundary for watershed protection, and relocated the headquarters to Arco. The former provision was to solve the nagging issue of northern unit's boundary adjustment, and the latter provision to relieve staff from working in cramped facilities and to assist in public relations. It also would have engaged the Park Service in a joint management venture with the Atomic Energy Commission of the Experimental Breeder Reactor-1 (EBR-1). In all, the plan called for approximately 300,000 acres to be added to form a park of 354,000 acres. [88]

Fritz's plan reflected his broad agenda for the monument. His park proposal, for example, joined issues of expanding the wilderness area and alleviating growing tourist pressures on the monument's existing facilities. But selling parks to Idaho was one of his main missions. An important element of his message was that park designation and expansion would bolster local economies through increased tourism. As with the pursuit of his other goals, Fritz's park plan was not well received by his superiors. Unlike other instances, though, when a new master plan had been denied, the Park Service deduced that now there were legitimate reasons to undertake a new study. Recreation in southcentral Idaho was building, especially in Idaho's national forests, and it would only rise with the newly designated Sawtooth National Recreation Area. It was thought, then, that tourist travel would increase in the region, and Craters of the Moon would feel the impact. Already the shoulder months in the spring and fall were showing signs of heightened use.

In 1973, the Park Service and Denver Service Center embarked on an expansion study that would recommend whether enlargement was warranted, and once completed, if it merited redesignation of the monument as a national park. The study also was to assess the area's current administrative conditions, its visitor use and experience, and its role in future recreational developments in southern Idaho. Planners devised five alternatives for the monument's expansion, most of which resembled Fritz's proposal. The addition of three contiguous areas was considered: the northern unit, the Craters of the Moon Lava Flow southwest of the monument, and the Great Rift south to Blacktail Butte. To this the other alternatives merely added on flows and features until reaching the entire size Fritz had proposed.

But that was as far as the plan went. In 1974 Fritz transferred and the issue was dropped. Regional Director Rutter had not been keen on the idea. And while there were good reasons for preserving the entire Great Rift for scientific purposes, the Park Service worried that creating such a large park might be administratively cumbersome. It could also appear as a land grab, alienating the agency from private land owners--graziers and hunters--and the Bureau of Land Management--which managed most of the land under study. In the bigger picture, what took place at Craters of the Moon might ruin the Park Service's chances of creating new sites in other areas of the state. Whether the monument would be enlarged and classified as a park remained to be answered by another study team and Congress some fifteen years later. [89]

In the economically stable period of the early 1970s, the proposal did not gain strong public support. Agricultural communities surrounding the lava monument were doing well financially, and added tourist dollars from a national park did not seem to strike any chords. By the mid-1980s, times had changed. Some rural towns were slumping, and tourism and the idea of a park in the lavas resurfaced with fervor. From 1985 to the early 1990s, expansion and national park status gained its most powerful thrust in the monument's history, culminating in another NPS study and legislation introduced into Congress. The 1980s' movement reflected the earlier creation period. It spawned the formation of a committee dedicated to the cause, maintained an economic interest in tourist income, and enlisted state congressional support.

The movement for the current park status and expansion germinated in 1985 with the proposed Minidoka-Arco Highway. The plan, developed by a group of local businessmen from southern Idaho, pushed for paving a sixty-mile dirt road cutting through the lavas between Arco and Rupert. Boosters saw it as a way to expand local markets, particularly for farm products, within the region--especially those communities associated with the Idaho National Engineering Laboratory. Two years later, some of the same individuals involved in the Minidoka-Arco Highway Committee, including former governor John Evans, revived the Craters of the Moon park proposal, and formed the Craters of the Moon Development Inc. Paul Fritz, now a consultant, assisted, and because he included the proposed road as the park's major thoroughfare in his resurrected plan, the two ideas merged. Once more the perceived benefits of an enriched economy influenced supporters of the park idea. The road would not only connect small intraregional towns, but also infuse the depressed region with park tourist dollars. [90]

Endorsed by local chambers of commerce, the park movement reached the state level in March 1987 when the Idaho State Legislature memorialized the "U.S. Congress to redesignate Craters of the Moon National Monument as Craters of the Moon National Park." [91] As the 1987 resolution shows, the state as well recognized the economic benefits a park would generate through increased tourism. The economic downturn of the period and the welling of state pride with the approaching 1990 centennial altered past aversions to creating a park in Idaho. Redesignation would not only give the state its first national park, but also would create "more publicity for Idaho and thereby attract more tourists to the State." As a result, all communities would benefit.

The state also believed that such a change was essential because the area better fit the definition of a park than a monument. Curiously, the state's argument rang with the ambiguities surrounding monument and park status aired in the early 20th century. Other parks such as the Grand Canyon, it stated, started off as monuments and were given park classification. Therefore, since the monument was established during this period when little distinction was afforded between the two categories, "the time is due now for Craters of the Moon to receive National Park status." Administratively nothing would change; the state stressed only a switch in status not size. Thus it seemed clear that the upgrade would help fill the state's coffers and bolster its stature.

The movement, however, involved both additional acreage and reclassification. It received congressional support from Idaho Democratic Representative Richard Stallings. In the fall of 1987, Stallings requested that the Park Service conduct a formal study for park status. The Park Service did not respond to his request immediately, and the state's Republican delegation seemed uninterested. Nevertheless, the movement sustained its momentum. In April 1988, Governor Cecil Andrus, expressing his "enthusiastic support" for park designation and expansion, appealed to NPS Director William Penn Mott for assistance. [92]

Public interest and political pressure paid off. Mott promised Andrus that as part of the monument's general management planning process the Pacific Northwest Regional Office would "explore the suitability/feasibility of designation of the area as a national park." Planning teams would also consider adjacent sites for possible expansion. [93] In March 1989, a Park Service team followed through on the director's pledge, completing a reconnaissance survey of lands to the southwest and southeast of the monument.

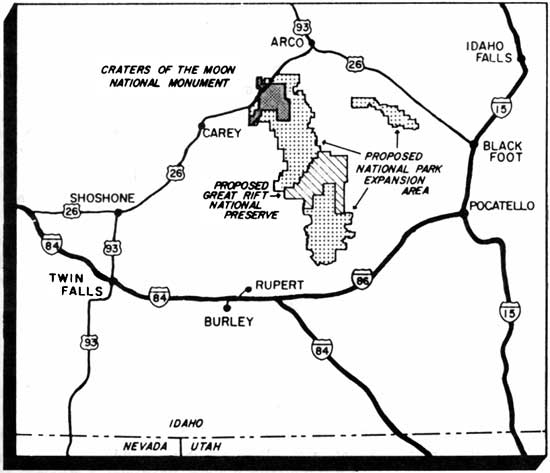

The survey covered essentially the same landscape of the 1970s' investigation. Forming an oval shape, it began with Shoshone as the westernmost point, and arced south through Minidoka, northeast to Blackfoot, northwest to Arco, and southeast through Carey. The land studied fell under various forms of public ownership, administered by the Bureau of Land Management, the National Park Service, and the state of Idaho; other lands were withdrawn for military use, administered by INEL, and a small percentage were privately owned. The major volcanic features evaluated in the study were similar to the earlier study as well. The entire Great Rift system and its four rift sets were considered, adding Open Crack to the previous three that were considered. [94] The study team concluded that the Great Rift was nationally significant, yet sites outside the system, such as Big Southern Butte and Cedar Butte, while interesting in and of themselves, were not nationally significant. Hence the Great Rift system was a viable "addition to the national park system," but it did not possess the "diversity of features generally associated with a national park and would best fit in the monument category." [95]

Congressman Stallings, presumably convinced that park status was in fact feasible, introduced a bill to Congress on November 20, 1989 "To designate certain public lands in the State of Idaho as Craters of the Moon National Park and the Great Rift National Preserve." [96] Under H.R. 3782, the Park Service would manage four units. Craters of the Moon National Park would expand the former monument by 320,240 acres for a total of 373,785 acres. It would be composed of three units: a large section of the Great Rift system (Craters of the Moon Lava Flow and the Crystal Ice Caves and Wapi Flow areas), and lands east of the Rift surrounding Big Southern Butte and Cedar Butte. The fourth unit, the Great Rift National Preserve, 123,040 acres, would contain the Open Crack and a section of the King's Bowl rift sets and connect the northern and southern units of the park. Both the park and preserve would amount to approximately 500,000 acres, most of which was formerly administered by the BLM. [97]

While the National Park Service remained neutral on Stallings' legislation, it expressed reservations over the bill's provisions. The continuation of grazing in certain allotments and allowance of hunting in the proposed Great Rift National Preserve were incompatible with standard NPS policies. It seemed that these conditions would cause management conflicts between the Park Service and Bureau of Land Management with their different management philosophies, especially if they shared similar tracts of land such as existing grazing allotments. The Park Service also voiced concerns over the high costs of developing the south park unit for visitor safety and enjoyment, tending to mining claims and state and private lands, and acquiring lands possibly contaminated with hazardous waste. In addition, there were an array of management and public use problems with hunting and grazing spilling over into the park from the proposed preserve since there were no clearly definable boundaries in the new areas. Unnatural boundaries also posed the need for more wilderness surveys, and begged rethinking to simplify agency management and avoid potential friction of different users. And finally, the Park Service did not share the optimism of park supporters that a park would be a tourist boon. [98]

Overall, the Park Service stood by its 1989 recommendation. The Great Rift system was nationally significant but did not deserve designation as a national park. Furthermore, increased protection did not need NPS management; modifications in BLM management could ensure protection for the majority of the expansion area because most of it fell within the BLM's proposed wilderness area. But due to public interest and resource significance, Idaho's congressional delegation requested that the Park Service draft a study of alternatives.

Recognizing that the main points of contention for both proponents and opponents was a lack of "consensus on the boundaries and management concepts," the study team presented six alternatives to the public at hearings in Arco, Burley, and Pocatello, Idaho in May 1990. Without funding for field investigations, the team's proposals represented conceptual rather than exact alternatives, but it was clear that the agency wanted to eliminate the costs and management complexities associated with Stallings' bill.

Except for taking "no action" and implementing H.R. 3782, all of the proposals eliminated the Big Southern and Big Cedar Buttes additions and did not ensure highway construction. One alternative suggested renaming the monument as a park, while another suggested creating a Great Rift National Science Reserve. The reserve would incorporate those lands along the Rift contemplated for expansion and leave them under BLM management in cooperation with various educational and federal agencies devoted to research and preservation. The final two alternatives proposed cooperative management between the Park Service and the BLM to continue traditional yet compatible uses while at the same time maintaining resource protection and public enjoyment. One plan would create the Great Rift National Park and Preserve, the park under NPS management and the preserve under BLM management. The other plan would establish a Craters of the Moon National Monument and Great Rift National Conservation Area, the monument under NPS jurisdiction and the conservation area under the BLM. In both cases similar sections of the Great Rift system would be included. [99]