|

CRATERS OF THE MOON

Administrative History |

|

Chapter 7:

RECREATION MANAGEMENT

In his 1918 letter instructing National Park Service Director Stephen T. Mather on how parks should be managed, Interior Secretary Franklin Lane wrote that "Every opportunity should be afforded to the public, wherever possible, to enjoy the national parks in the manner that best satisfies individual tastes." This philosophy enabled Mather to encourage mass use of national parks and in doing so win wide support, yet at the same time it forced the Park Service to address the dilemma inherent in its mission--how to reconcile the "agency's role as the preserver of the great scenic places with its role as a provider of recreation opportunities to much of the American public." In short, preservationists worried that high tourism would diminish the wilderness values of parks, while tourist groups sometimes protested the lack of adequate facilities and, by association, lack of recreational opportunities in national parks. Attempting to please both sides, the Park Service steered a middle course. [1]

At Craters of the Moon, recreation management has attempted to do the same by allowing visitor activities that are compatible with the monument's founding purpose. Overall, management embraces outdoor activities such as camping, hiking, picnicking, skiing, biking, and cave exploration. Most of this takes place within the monument's developed section; however, Craters also offers primitive recreation in its expansive wilderness and backcountry areas. While recreation rarely elicits management conflict, visitor use of any sort within the monument, as detailed in other sections, requires mitigation policies. Likewise, external recreational developments--potentially adjacent to and beyond the control of Craters of the Moon--demand equal attention for their possible interference with the visitor's experience and resource qualities.

Given the monument's volcanic terrain, desert environment, and small area of development, most visitor recreation has been concentrated around the loop drive and the features located along it. The monument's landscape lends itself well to daytime activities, the predominant use, for the most scenic sites and formations are easily seen within several hours by car. Without the popularity of the automobile and the advent of modern highways, it is unlikely that tourists of any time period could have visited or enjoyed Craters of the Moon on a large scale. This is not to say that all were alike. Tourists during the monument's first decades were required to be more adventurous than their later counterparts; to see some of the natural phenomena, they had to hike into the interior, later accessible by extensions to the loop drive. Except for the intrepid Robert Limbert and other explorers and scientists like him, the majority of visitors toured the monument along the primitive loop drive, and picnicked, camped, or, beginning in the 1930s, spent the night in the Craters of the Moon Inn. Sightseeing was the most popular activity, as visitors circulated among the outstanding natural features, engaging in small excursions and drinking in the vistas.

SKIING

In the late 1930s and early 1940s, downhill skiing and other winter sports activities grew in popularity at the monument, as area residents slid down snow-covered cinder cone slopes during winter months when Craters was closed. [2] Skiing compelled the Park Service to establish its first recreation policy regarding the development of winter sports facilities at Craters of the Moon. The Arco Civic Club asked the National Park Service, on August 5, 1941, for permission to build a winter sports facility on the northeastern slope of Sunset Cone. The club felt that the cone's proximity to the highway and the eastern boundary, and its lack of scenic qualities associated with the "main attractions" elsewhere in the monument would not interfere with the area's mission. The cinder hill, from this perspective, was far more valuable for recreation. [3]

The request caught the agency off guard. The monument's master plan carried no provisions for winter sports development, and Acting Regional Director Herbert Maier expressed reservations about granting this type of program at all, citing prohibitive development and maintenance costs. [4] The agency left the situation to Custodian Guy E. McCarty. The following summer McCarty reported that at first the civic club thought the Park Service should construct a ski lift in order to attract more visitors. McCarty informed the group that it was not NPS policy to lure visitors with constructed "attractions." Undeterred, the Arco Civic Club next hoped to install its own ski lift at the site, and owners of a rope tow, operating on private land just north of the monument, voiced an interest in moving the lift to and constructing a small-scale operation on Sunset Cone. McCarty favored development of some kind to accommodate the ski resort's supporters, a group of monument boosters from the Arco and Lost River areas who were just seeking "a place to get out for recreation," during a period when alpine rather than nordic skiing was the preferred sport. [5]

Regional Director O.A. Tomlinson made it all but impossible for the civic club to create a winter sports facility at the monument without overtly denying the proposal. Tomlinson stated, as had McCarty, that NPS policy was not to attract visitors with man-made features, but rather to showcase natural phenomena, and this philosophy applied to Craters of the Moon. More importantly, the regional director noted that a February 1940 winter-use policy decision by the Park Service emphasized that no developments should impair an area's scenic values, and that the entire proposed facility would have to be dismantled each season in order to comply with agency policy. In the case of Craters of the Moon, he agreed to award a permit only if the operators did not clear the slopes in any way and if they removed their buildings and equipment each spring. He also urged the operators to seek another site, which would be less expensive for all concerned. [6] No discussion of development continued after Tomlinson's decision; McCarty issued no permit, and no facility was established. Despite the civic club's impression, the monument's scenic qualities prevailed over the perceived need for recreational developments.

For a time, the sport of choice was snowmobiling around the loop drive, until Superintendent Robert Hentges ended the activity in the 1970s, finding that it was harmful to the delicate cinders if the snow machines wandered off course. The energy crisis of the early 1970s also contributed to this trend, and more traditional winter sports, again, gained in popularity. To conserve fuel, managers no longer plowed the loop drive to Devil's Orchard, yet Superintendent Paul Fritz observed that cross-country skiers and snowshoers would likely take advantage of the snow-covered road. [7] In the mid-1980s, Superintendent Robert Scott began promoting a cross-country ski program at the monument. The intention of the program was to provide groomed trails for skiers. [8] Furthermore, Scott explained that the "purpose of this service is to provide a method for winter visitors to use and enjoy the park. As the roadway is not kept snowfree from mid-November through mid-April, there is little opportunity for park visitors to explore beyond the visitor center except by traveling over snow." [9]

By the 1987-1988 season, the program lay in its incipient stages; a donated snowmobile and grooming equipment allowed monument managers to lay down tracks along the loop drive. Around one hundred visitors skied the trails. The following season use increased, and the monument charged a $2 user fee, and the Interpretation Division provided a free activity and safety handout for skiers. Winter skiing at the monument had a long history, yet this was the first time park staff had engaged in such a program. Still considered in its initial stages of development as of the early 1990s, the winter skiing service has continued to be a popular winter program. [10]

WILDERNESS/BACKCOUNTRY MANAGEMENT

While most recreation takes place within the monument's small developed area, a small amount of recreation takes place within the monument's large undeveloped area. Eighty percent, or 43,243 acres, of the monument's land base is wilderness, while another approximately 18 percent, or 9,287 acres, is considered to be backcountry--an undeveloped natural environment. [11]

Established October 23, 1970, the Craters of the Moon Wilderness Area had encountered some turbulence in its creation, none of which, however, influenced its smooth management. No pressing issues confronted the environment; designation affirmed the "backcountry" management classification affixed earlier to the remote region of the monument. As one of the first two NPS areas with a designated wilderness area, Craters of the Moon was breaking new ground in management. Yet the wilderness classification altered little in past management practices, and the most significant administrative concern revolved around setting down a wilderness management policy--based largely on the pattern of low backcountry visitation.

Wilderness, or backcountry, management predated the formal creation of the monument's designated wilderness area. After proposing the southern portion of the monument for wilderness classification in May 1965, Superintendent Roger Contor established a number of guidelines for managing the area based on a philosophy of primitive recreation. All use required minimum impact practices, a policy still adhered to today. One of the first actions was the closure of the area to vehicle traffic with the erection of a barricade "on the old fire road at Coyote Butte." As Contor noted, the "Tutimbaba," the proposed name, was "as untrammeled and pristine as any wilderness in the United States." Its natural resources were "almost completely unchanged by the influence of man." And evidence of Native American use was "abundant." "Like other wilderness areas," he predicted, "it will offer Americans a chance to escape civilization and enjoy a world where man is only a passing shadow." [12]

One of the most important management considerations was to "retain the solitude, the wildness, and the opportunity for self determination," the superintendent noted. Thus, "we plan to install no trails (other than about 1 1/2 miles of the old fire road), campsites, self guiding interpretive exhibits or identification signs." The visitor's only guides would be a wilderness pamphlet, describing the environment and regulations, and a topographic map. Furthermore, the monument would encourage overnight campers "to use backpacking stoves...rather than campfires, to minimize fireplace and axe scars at the more popular stopping points. All litter and refuse should be carried out just as it was carried in--on the owner's back." [13]

The harsh environment of the lava country, Contor believed, dictated this management direction. Its heat and aridity contributed to a primarily day-use visitation pattern, with few overnight users, and low visitation overall; less than one hundred visitors ventured into the wilderness annually in the mid-1960s. Those who hiked the primitive backcountry tended to be more experienced and practiced low-impact camping techniques, and therefore caused little resource deterioration.

Policy, then, focused on prevention of future impacts. Contor's 1966 resource management plan embodied these principles and the guidelines he had established the previous year. The plan stressed day use over the more disruptive overnight camping with its attendant "camp sites," fires, trash, and resource erosion. Overnight use would be allowed through a free permit system, whereby campers would be directed away from significant and delicate natural features. Along these same lines, the superintendent advocated prohibiting overnight horse use, if necessary, due to the stress horses imposed on the sparse waterholes and vegetation, as well as unique volcanic formations. Because wildlife depended on the scattered waterholes, whose levels seemed to be on the decline, campers and horses were not to use them. In addition, stagnant water posed a human health risk. No special provisions were necessary, though, since the holes were difficult to locate in the lava expanse. As for developments, the plan held to earlier guidelines, stating that the monument would neither build nor maintain trails, adding that numerous wildlife trails and easy topography negated these amenities. Only camping zones rather than formal campsites would be designated, with fires restricted to specified sites. The most important aspect of management, perhaps, centered on visitor education and safety information disseminated through pamphlets; primitive trail signs would show the way, and ranger contacts would ensure, as much as possible, visitor as well as resource protection. [14]

Superintendent Paul Fritz and his staff drafted the first backcountry/wilderness management plan in 1972. This document as well as the subsequent 1976 plan written by Superintendent Robert Hentges reflected much of Contor's guidelines; one stipulation was that stock use was limited to forty horses per party. As in the previous decade, visitation still hovered around one hundred overnight users and governed policy--in that there was no pressing need to institute changes in the program. Hentges offered, though, a few revisions to Contor's standards. To emphasize and increase the day-use pattern and at the same time simplify wilderness access, Hentges built a spur trail from the Tree Molds Trail to the main wilderness trail in 1976; along with entrances at Buffalo Caves and Broken Top, this extended wilderness access to three locations. [15] Overnight campers were still managed through a permit system, yet the Hentges' policy did not call for designating or assigning campsites, or restricting use near specific features. Rather, rangers would take the initiative and suggest sites to camp. Hentges also prohibited wood fires altogether in the wilderness, as part of the monument's fire policy in force by 1976. A main concern involved future visitation trends and wilderness carrying capacity, yet low use and minimum impacts characterized the situation in the mid-1970s. Hikers did not penetrate deep into the wilderness. It was expected that use at some point would increase, but slowly, causing no immediate threat. [16]

As implied by both the 1966 and 1976 policies, wilderness was nearly self-managing. The central factor was the amount and type of use, and until both rose dramatically, policy remained the same. The wilderness area's hostile environment and popularity of adjacent Forest Service recreation and wilderness areas, with their less extreme conditions, operated against a dramatic increase in backcountry visitation. [17]

Subsequent wilderness management plans have retained the major principles outlined in previous documents. [18] Hentges, in the 1982 resource management plan, stressed the continuity in wilderness management. For instance, the permit system formed an important management tool because it enabled monument officials to monitor and ensure visitor safety and activity, to protect water resources, and prevent adverse resource impacts. In more than thirty years since the creation of the monument's wilderness area, backcountry use is still light and this fact still guides present policy in the most recent wilderness management plan approved in November 1989.

This plan, however, advanced the approach of past documents. It recognized, for instance, that the monument has the "opportunity to manage" the wilderness in order to preserve its "wilderness character and prevent impacts, rather than try to restore that character through mitigation of impacts." Surrounded on three sides (the east, south, and west) by the Bureau of Land Management's proposed Great Rift Wilderness Area, 341,000 acres, the monument's wilderness seemed well insulated from external threats. It was important then to institute stricter guidelines for internal use. Although the Limits of Acceptable Change System is the standard program for determining wilderness impacts and management responses, Craters of the Moon's low level of use (still averaging around 120 overnight campers) and near "pristine" wilderness conditions rendered this approach impractical. Instead the plan opted for an active resource monitoring program "to assure resource protection." [19]

Moreover, the document defined three opportunity classes in the monument's backcountry to better protect the resource and "provide a variety of wilderness and backcountry experiences." Of the three classes, backcountry, primitive, and pristine, the latter two applied to the monument's wilderness. The primitive zone, a tongue-shaped corridor about a mile wide and three miles long, enclosed the most commonly-used areas in the wilderness--the Tree Molds Trail south along the Great Rift to the popular camping area of Echo Crater. Although considered minimal, here the most impacts and social contacts occurred, and it is here that the "management strategy was to restrict impacts to previously impacted areas." Therefore, campers were encouraged to use former, yet undeveloped, camp sites. The plan also reduced the number of horses per group from forty to twelve. This change reflected pressure from the regional office's wilderness steering committee, headed by former monument naturalist Edgar Menning, and resulted in a short-lived protest by local stock users. The remaining wilderness area was considered as the pristine class, its use characterized almost as the opposite of the primitive class. It received the minimum of use and impacts, and the management "strategy" was to "disperse any use to avoid impacts." This means campers were encouraged to camp in unimpacted sites, move often, and leave behind no signs of their presence. [20]

Essentially, these classifications recognized existing conditions and stipulated acceptable activities in each. In a sense, the backcountry class did the same thing. This undeveloped and natural environment outside of the wilderness boundaries is made up of those lands buffering the monument's wilderness and the northern unit. In the winter months, mid-November to mid-April, the frontcountry serves as the backcountry, since the loop drive is closed by snow and winter sports activities take over. Although no overnight camping is allowed in the backcountry zone, skiers are allowed by permit to camp in the Caves Area parking lot. Similarly, during the spring, summer, and fall months, overnight camping is permitted in the group campground in the northern unit. Use of the northern unit, considered a sensitive area because it contains the monument's drinking water, was otherwise tightly controlled. In the early 1980s, monument officials began to allow day hikes, and were soon forced to require a permit, not to prevent water contamination but to protect the mule deer herd from hunters. One hunter would take a "hike," flushing deer from the monument, which were then harvested by another hunter on the boundary. By making hiking illegal without a permit, this activity ended, and no permits are issued during hunting season. Although no motorized or mechanized vehicles are permitted in wilderness, beginning in 1990, Superintendent Robert Scott implemented a new backcountry management program, allowing bicycles in the northern unit on established roadways, and subject to the same permit system as hikers. [21]

Although the recent management plan has created some changes, the general rule still applies. Until visitation increases enough to impair wilderness and backcountry resources, there is little change foreseen in the course of management. In a sense, what gives the backcountry its wilderness qualities, a harsh and remote volcanic landscape, assures its continued "pristine" state.

|

| Horse travel in the monument wilderness is a popular form of recreation, ca. 1965. (CRMO Museum Collection) |

WINDSHIELD TOURISTS AND EXTERNAL THREATS

Recreation management shifted somewhat in the mid-1950s with the onset of the Mission 66 program. Although Superintendent Aubrey Houston raised the idea of constructing a winter sports area at the monument as a method to raise revenues for needed development projects, the Park Service instead concentrated on the development program outlined by Mission 66. [22] The 1956 Mission 66 prospectus symbolized the theme of automobile tourism. Driving rather than hiking was now the American public's preferred mode of access. In this plan, Superintendent Everett Bright noted that improved roads and trails, as well as interpretive programs, would assist in boosting recreational opportunities. [23]

Subsequent management plans concentrated on improving recreation where visitor use would most likely be felt--in the traditional and primary visitor activities. An extension of the loop road around Big Cinder Butte represented one way to expand on sightseeing and interpretation; another was to create more entrances and lighting in the developed caves, and to remodel the present campground into a picnic area and construct a campground twice as large in the northern unit. [24]

Although these plans did not unfold as conceived, they demonstrate Craters of the Moon's management philosophy of encouraging recreation in the lava landscape. A further statement of this commitment, for instance, has been the monument's promotion of primitive outdoor activities in the newly created wilderness in 1970. A more recent variation has been to allow backcountry hiking, biking, and possibly skiing in the foothills of the northern unit. [25]

Recreation within Craters of the Moon's boundaries is more easily controlled than those outside them. To date Craters of the Moon has avoided the clashing values of recreational development and the preservation of natural and cultural resources within the monument because no conflicts have arisen. Currently, the threat of external development revolves around the potential of such developments to occur. The Blizzard Mountain Ski Area, a small operation near the northeastern boundary, for instance, never posed a real threat having run intermittently since its inception in 1962. Superintendent Roger Contor even noted that the ski area's existence relieved the monument of the pressure to development such an installation. [26] On the northwestern boundary, development of a tract of 2,700 acres of private land in the Big Cottonwood drainage has simmered for more than a decade. Development concepts include winter and summer resort activity, which, given the right economic climate, could severely impact monument resources. And as recent comprehensive management plans have addressed, regional recreational developments could also affect the monument. [27]

All things considered, Craters of the Moon contains a variety of outdoor pursuits for visitors in a relatively small landscape. The loop drive and attendant trails enable tourists to sightsee as well as to take short hikes to and among the monument's outstanding features. Wilderness and backcountry areas add a more primitive dimension to recreation. As recent development plans indicate, the nature of the visitor is changing. Overnight camping in a day-use area has increased, the appearance of recreational vehicles has surged, and the visitor season has expanded. As a result, the general development plan calls for expanding campground facilities and renovating the monument's road system to accommodate these trends. While it is difficult to predict the future, these trends seem to indicate that the traditional center of recreational activity, the frontcountry, will feel the greatest effects. [28]

|

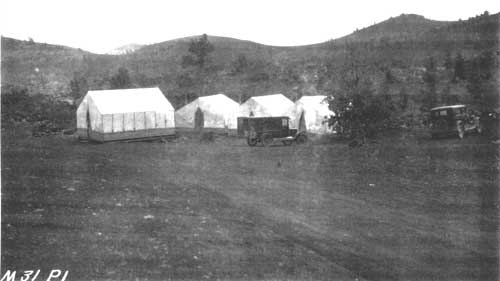

| Auto camping at Craters of the Moon National Monument, ca. 1931. (CRMO Museum Collection) |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

adhi/chap7.htm

Last Updated: 27-Sep-1999