|

Cumberland Gap National Historical Park Kentucky-Tennessee-Virginia |

|

NPS photo | |

Stand at Cumberland Gap and watch the procession of civilization, marching single file—the buffalo following the trail to the salt springs, the Indian, the fur-trader and hunter, cattle-raiser, the pioneer farmer—and the frontier has passed by.

—Frederick Jackson Turner, 1893

Crossing the Great Mountain Barrier

From Alabama to Canada the Appalachian Mountains rise in a series of parallel ridges between the eastern seaboard and the continent's interior. If you were heading west in the days of travel by horse, boat, or your own two feet, crossing points were few and far between.

Mid-18th century explorers following well-worn bison and American Indian trails found their way through at Cumberland Gap. Their discovery opened the Ohio Valley to the first great wave of westward migration. Today at Cumberland Gap National Historical Park you can walk in the footsteps of yesterday's travelers—men, women, and children propelled by dreams and determination.

The route through the gap was first brought to widespread attention by Dr. Thomas Walker, who had been hired to stake out an 800,000-acre grant beyond the Blue Ridge. In 1775 a longhunter named Daniel Boone was commissioned to blaze a road through the gap. Boone's trace evolved into the Wilderness Road, establishing his place in history as a frontiersman and pathfinder.

Settlers immediately flooded into the Ohio Valley. Less than a decade after the end of the Revolutionary War, Kentucky became the 15th state. Though other routes were used, the Wilderness Road through Cumberland Gap was the primary way to the West until 1810.

In the 1790s traffic on the Wilderness Road increased. In the years 1780-1810 between 200,000 and 300,000 people crossed the gap heading west. There was eastbound trade traffic as well: crops, corn whiskey, and herds of livestock.

With a nation that now spanned the continent, long-distance transportation quickly improved in the first half of the 19th century. Canals, railroads, and well-engineered wagon roads crossed the Appalachians. Cumberland Gap declined in importance. Then during the Civil War both sides considered the gap strategic. By the end of the war the gap had charged hands several times, yet it saw no major action.

In the 20th century, Cumberland Gap (and its associated roadways) continued to be a major economic artery for the Appalachian region. When Cumberland Gap National Historical Park was authorized by Congress in 1940, U.S. 25E, a major paved highway, passed through the gap, compromising the historic scene known to Indians and early settlers. To restore the historic landscape the highway was rerouted through the Cumberland Gap Tunnel, which opened in 1996. Over the next years the gap area was restored to the way it looked around 1810. Today you can see and experience the natural beauty of Appalachian mountain country.

What a road have we passed! certainly the worst on the whole continent, even in the best weather; yet, bad as it was, there were four or five hundred crossing the rude hills ... men, women, and children, almost naked, paddling barefoot and bare-legged along, or labouring up the rocky hills, whilst those who are best off have only a horse for two or three children to ride at once.

—From journal of Francis Ashby, 1803

Cumberland Gap Timeline

Long before humans came here, elk and deer in search of food trampled a path through the gap. For American Indians the gap was a vital pass to hunting grounds in what would later be Kentucky. It was also the key pass on the Athawominee ("path of the armed ones"), or the Warrior's Path, the trail of trade and war.

Cumberland Gap is one of the very few natural corridors through the Appalachian Mountains. When Americans started migrating westward in the 1770s, the primary route was southwest via Virginia's Great Valley Road, through Cumberland Gap, north through The Narrows (Pineville, Ken.) and into the Kentucky Bluegrass country and the Ohio River Valley.

1750

Gap explored by Dr. Thomas Walker and five companions. Hunting parties use gap

passage thereafter.

1769

Daniel Boone makes his first passage through the gap.

1775

Boone and others blaze Wilderness Road through gap, opening Kentucky lands to

settlers.

1776-1810

200,000 to 300,000 settlers cross Cumberland Gap into Ohio Valley.

1792

Kentucky becomes 15th state; first west of Appalachian Mountains.

1796

Tennessee becomes 16th state.

1796

Wilderness Road improved and opened to wagon traffic.

1800

The Wilderness Road through the Cumberland Gap became a two-way thoroughfare. As

the stream of settlers moved west, thousands of cattle, sheep, pigs, and

turkeys—along with corn whiskey—from western farms traveled east to

the seaboard markets.

1806

Meriwether Lewis and William Clark pass through gap (separately) on the return

leg of their expedition.

1830s and 40s

Wilderness Road declines in importance as canals and railroads improve east-west

travel elsewhere.

1861-65

Considered strategic by both sides during the Civil War, gap changes hands

several times but sees no major action.

1864

Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, inspecting garrison, titles Cumberland Gap the

"Gibraltar of America."

1889

Railroad tunnel completed under gap.

1908

Federal government completes Object Lesson Road, a project demonstrating modern

road-building methods.

1920s

U.S. 25E constructed through gap

1940

Cumberland Gap National Historical Park authorized by Congress; established

1955.

1996

U.S. 25E road tunnel completed, bypassing gap.

2002

Gap landscape restored to 1810 appearance.

Dr. Thomas Walker

Dr. Thomas Walker, surveyor for the Loyal Land Company, became the first white man to explore, describe, and document the route to the gap. Walker's 1750 account describes things we can see today such as the entrance of the present Gap Cave, the spring emanating from it, and the Indian road Walker followed. "This Gap may be seen at a considerable distance," he wrote, "and there is no other, that I know of, except one about two miles to the North of it, which does not appear to be so low as the other."

Daniel Boone

No name is more associated with Cumberland Gap and the opening of the West than Daniel Boone's. Born near Reading, Pa., in 1734, Boone became renowned as a hunter and rifleman. In 1775 the Treaty of Sycamore Shoals secured a large portion of the Kentucky country from the Cherokees. That year Boone and 30 men marked out the Wilderness Trail from Long Island on the Holston River (Kingsport, Tenn.) through Cumberland Gap into Kentucky. There he founded Boonesborough and eventually held several positions in local government.

The Many Faces of Cumberland Gap

Cumberland Gap National Historical Park introduces you to faces and places from the era of westward migration. You are invited to join in the park's campfire programs, hikes, walks, music and craft demonstrations, tours of Hensley Settlement (a historic Appalachian community), and other activities scheduled throughout the year.

Begin at the visitor center where you will find an information desk, exhibits, orientation and history films, and book and map sales. Cumberland Crafts sells works by Southern Highland Craft Guild members. Guild artists and artisans give demonstrations,

From the visitor center you can drive a winding four-mile-long road up the mountain to the Pinnacle Overlook (elevation 2,440 feet) for a spectacular view into the three states of Kentucky, Virginia, and Tennessee.

The Many Places of Cumberland Gap

Fern Lake occupies one of the many valleys in this region dominated by mountain ridges.

Drive or hike to Pinnacle Overlook for a spectacular view of three states—Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia.

Many of the park's most interesting features, like Skylight Cave, are reached only by trail. The park maintains some 70 miles of trails, ranging from 0.25-mile to 21 miles.

Here you are in the heart of Southern Appalachian Mountains habitat which includes ferns and the spring blooms of the trillium .

Gap Cave (formerly Cudjo's Cave) is open to visitors by ranger-led tour only. Look for cave crickets, bats, salamanders, and a large variety of cave formations.

White Rocks, at the eastern tip of the park atop Cumberland Mountain, is accessible via the Ridge Trail or trail from Civic Park.

Hensley Settlement is the early 20th-century homestead of the Hensley and Gibbons families. A ranger-led tour takes you through original buildings and farmland.

Planning Your Visit

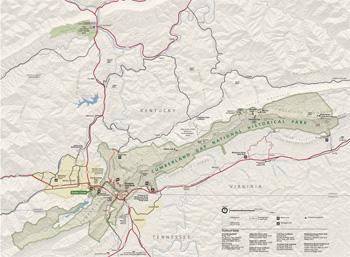

(click for larger map) |

From I-75 in Kentucky, exit onto 25E at Corbin and go south 50 miles to park entrance. From I-81 in Tennessee exit onto 25E at Morristown and go 50 miles north. From U.S. 58 in Virginia go west to the intersection with 25E. The park gates are open 8 a.m. to dusk year-round. The visitor center, on U.S. 25E, 0.25 mile south of Middlesboro, is open daily 8 a.m. to 5 p.m.; visitor center is closed December 25.

Trails Almost 70 miles of hiking trails wind through eastern deciduous forest in this 20,000-acre national park. Distances range from a 0.25-mile loop trail to the 21-mile-long Ridge Trail. Maps of trails open to horse use are available at the visitor center.

Hensley Settlement Go home to the mountains! The 3½-hour tour includes a one-mile walk through the settlement, so wear comfortable shoes and bring a light snack. Reservations recommended; fee.

Gap Cave Tours Join park rangers on an exciting two-hour adventure exploring this majestic underground cathedral. The one-mile tour includes three levels of the cave via 183 steps. For the safety of all, no children under the age of five are permitted. Reservations recommended; fee.

Source: NPS Brochure (2008)

|

Establishment Cumberland Gap National Historical Park — June 11, 1940 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

A Brief History of Hensley Settlement (Robert Ward Munck, undated)

An Evaluation of Biological Inventory Data Collected at Cumberland Gap National Historical Park: Vertebrate and Vascular Plant Inventories NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/CUPN/NRR-2010/182 (Bill Moore, March 2010)

Archeological Overview and Assessment of the Cumberland Gap National Historical Park, Virginia, Tennessee, and Virginia (Todd M. Ahlman, Gail L. Guymon and Nicholas P. Herrmann, July 2005)

Cumberland Gap National Historical Park (HTML edition) (William W. Luckett, ©Tennessee Historical Society, extract from Tennessee Historical Quarterly Vol. XXIII No. 4, December 1964)

Determination of Eligibility for the Pinnacle Overlook Developed Area, Cumberland Gap National Historical Park, Lee County Virginia and Bell County, Kentucky (North Wind Resource Consulting, LLC and Vint and Associates Architects, September 2023)

Feasibility Study: Eradication of Kudzu with Herbicides and Revegetation with Native Tree Species in Two National Parks NPS Research/Resources Management Report SER-59 (Aaron Rosen, April 1982)

Foundation Document, Cumberland Gap National Historical Park, Kentucky, Tennessee and Virginia (March 2016)

Foundation Document Overview, Cumberland Gap National Historical Park, Kentucky, Tennessee and Virginia (January 2016)

Geologic Resources Inventory Report, Cumberland Gap National Historical Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR-2011/458 (T.L. Thornberry-Ehrlich, September 2011)

John Muir's Crossing of the Cumberland (Dan Styer, extract from The John Muir Newsletter, Winter 2010-2011)

Junior Ranger Activity Book, Cumberland Gap National Historical Park (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Lincoln County, KY, Court Road Order: Davis Tavern Location (July Court 1798)

Location of the Wilderness Road, Cumberland Gap National Historical Park, Kentucky, Virginia, Tennessee (Jere L. Krakow, August 1987)

Location Study: Davis Tavern Site, Cumberland Gap National Historical Park, Kentucky-Tennessee-Virginia (Ricardo Torres-Reyes, December 2, 1969)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Forms

Cumberland Gap Historic District (Keithel C. Morgan, undated)

Hensley Settlement (Keithel C. Morgan, undated)

Natural Resource Condition Assessment for Cumberland Gap National Historical Park NPS Natural Resource Report NPS/CUGA/NRR-2013/620 (Gary Sundin, Luke Worsham, Nathan P. Nibbelink, Michael T. Mengak and Gary Grossman, January 2013)

Ozone and Foliar Injury Report for Cumberland Piedmont Network Parks: Annual Report 2008 NPS Natural Resource Data Series NPS/CUPN/NRDS-2009/012 (Johnathan Jernigan, Bobby C. Carson and Teresa Leibfried, November 2009)

Restoration of Historic Features: Wilderness Road, 1780-1810, Cumberland Gap National Historical Park (Harland D. Unrau, September 2002)

Restoration of Cumberland Gap and The Wilderness Road/Development Concept/Interpretive Prospectus/Environmental Assessment Draft (December 1989)

Sustaining the Landscape: A Method for Comparing Current and Desired Future Conditions of Forest Ecosystems in the North Cumberland Plateau and Mountains (Daniel L. Druckenbord and Virginia H. Dale, December 2004)

Task Force Report: Improvements to U. S. Highway 25 East and Restoration of Historic Cumberland Gap (J.T. Anderson, P.B. Coldiron, Patrick Fleming, J.L. Obenschain and Eugene R. DeSilets, October 14, 1966)

The Distribution of Exotic Woody Plants at Cumberland Gap National Historical Park NPS Research/Resources Management Report No. 52 (Teri Butler, Donald Stratton and Susan Bratton, June 1981)

Willie Gibbons House, Historic Furnishing Plan, Cumberland Gap National Historical Park (Keithel C. Morgan, October 1979)

The Cumberland Gap (Transcript) (Duration: 11:39, undated)

Cumberland Gap 1986 (National Park Service narrated by Lorne Greene)

cuga/index.htm

Last Updated: 09-Apr-2025