|

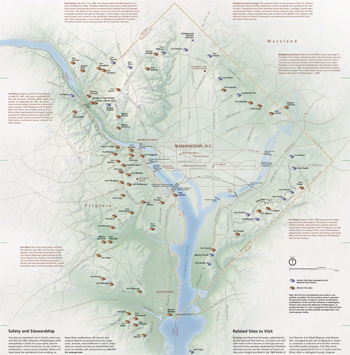

Civil War Defenses of Washington District of Columbia-Maryland-Virginia |

|

NPS photo | |

Civil War Forts, Present-Day Parks

Forested heights and inviting parklands—a rare backdrop to most urban settings—wrap a mantle of contrast around Washington, D.C. Even more uncommon are the exceptional natural elements and remnants of history located among the hills encircling the city.

High ground around Washington played a vital role in protecting the nation's capital during the Civil War. In i860 slave states sympathetic to the Confederacy surrounded the District of Columbia, which was protected only by the brittle brick bastions of Fort Washington, 16 miles south on the Potomac. As the prospect for war grew, tensions escalated, and Washington, D.C, lay vulnerable to attack. The Lincoln Administration realized the city urgently needed a stronger shield of defense, prompting the Federal government to seize strategic lands with views of essential roads, bridges, and waterways. As war broke out in 1861, Union forces quickly built a ring of earthen fortifications around the nation's capital and moved massive cannons into place. Hospitals and settlements sprang up nearby, providing shelter and work for many, including African American "contrabands" of war.

Most of the fortifications were dismantled or abandoned by 1866. Decades later, a plan to connect the historic sites with a scenic automobile route paved the way for their preservation. Although some elements of the Civil War Defenses of Washington eventually surrendered to time and urbanization, many fortifications and associated lands remain protected within the National Park System. Today parks and woodlands occupy the heights where heavy guns once scanned the horizon—and people stroll, hike, and bike where courageous soldiers once stood guard over the nation's capital.

By latest accounts the enemy is moving on Washington . . . Let us be vigilant, but keep cool.

—President Abraham Lincoln, Washington, D.C, July 10, 1864

The Defenses of Washington

Fortifying the nation's capital became the Union's greatest concern after the defeat at Manassas in the summer of 1861. Major General John G. Barnard, a West Point graduate and respected expert on coastal fort construction, accepted the massive task. Armed with engineers, soldiers, former slaves, and other laborers, Barnard developed a connected system of fortifications occupying every prominent point around Washington. Rifle trenches linked each strategic site and doubled as communication lines. By the end of the Civil War, the "Father of the Defenses of Washington" had directed the construction of 68 forts, 93 gun batteries, 20 miles of rifle pits, and 32 miles of military roads around the capital. As a result, Washington, D.C, became one of the most fortified cities in the world.

Earthen Fortifications

Military earthworks are fortifications constructed from dirt. Inexpensive and readily available, dirt produced very strong structures that could absorb the impact of projectiles better than brick or stone masonry. Soldiers and laborers worked with shovels and picks to build ramparts (walls), parapets (slopes), and bombproofs (shelters) following a standard procedure for construction. A dry moat (trench) and barricade of dead trees called an "abatis" surrounded each fort.

The Battle of Fort Stevens

By the end of 1863 heavily armed fortifications provided a perimeter of protection around the nation's capital. With 23,000 troops positioned in this ring of defenses, Washington officials felt the city was well prepared for Confederate attack.

The following summer, thousands of troops stationed around Washington, D.C, were sent to reinforce General Ulysses S. Grant at Richmond and Petersburg, Virginia. Only 9,000 poorly trained reserves remained to protect the city. Confederate leaders, including General Robert E. Lee, knew the time was right to strike Washington, D.C. By the afternoon of July 11, 1864, Confederate Lieutenant General Jubal A. Early and a force of 14,000 men had crossed the Potomac, fought at the Monocacy River near Frederick, Maryland, and encountered fire from Fort Reno, Fort DeRussy, and Fort Slocum. Early's Confederate force then assaulted Fort Stevens—only six miles from the U.S. Capitol.

Panic spread through the city. President Lincoln urged citizens to stay calm as additional Union troops arrived. On July 12, 1864, Lincoln visited Fort Stevens to encourage the men during the conflict and barely escaped a sharpshooter's bullet. Federal troops closed in, and the fighting ended by dusk. Early retreated when he recognized the unexpected strength of the reinforced defenses of Washington.

From Early Concept to Lasting Connections

The Civil War Defenses of Washington parks connect crossroads from the nation's divergent past to our present pastimes. Nearly 40 years after most of the Civil War fortifications were dismantled. Congress reviewed a proposal for a "Fort Drive" around Washington, D.C. The 1902 McMillan Commission Report concept included a modern roadway winding through a landscaped corridor that linked the forts. Between 1930 and 1965 the fortification sites and land acquired for the Fort Drive were transferred to the National Park Service, but a continuous roadway eventually proved impractical.

During the 1930s the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) provided jobs while enhancing park facilities. Reconstruction of a parapet at Fort Stevens and construction of Fort Davis Drive are only two of the CCC's most visible contributions throughout the circle of parks. More than a century later, historic locations within the Civil War Defenses of Washington remain linked by a ribbon of recreational opportunities and significant natural and cultural resources. One of the nation's earliest urban planning efforts now provides open space for public enjoyment and important habitat for native plants and animals.

. . . the points that are singled out by natural conditions as especially worthy of preservation are mainly hilltops from which extensive views may be obtained.

—McMillan Commission Report, 1902

Circle of Forts, City of Trees

From Forts to Forests

Strategic heights selected by Civil War engineers for the defenses of Washington overlooked major turnpikes, railroads, bridges, and shipping routes. At fort locations with dense woodlands, the Union Army cut down trees to create vantage points for observing approaches to the city. After the war, nature reclaimed many fort sites. Today, second-growth hardwood forests protect remnants of earthen fortifications and provide shelter for a variety of plants and animals. Trails meander alongside springs that slowly release rainwater purified by forest soils. Migratory bird songs mask the sounds of civilization. Such natural diversity is unusual so close to a city. It is this ribbon of green around Washington, D.C, that helps make the nation's capital so unique.

Visiting the Civil War Defenses of Washington

(click for larger map) |

The circle of fort sites around the city contains a captivating collection of historic Civil War fortifications, natural environments, trails, and parks. Many remain in the heights surrounding Washington, D.C., but some no longer exist. Detailed street maps may be required to find specific locations open to the public managed by either the National Park Service or other agencies. National Park Service sites are open every day from dawn to dusk except January 1, Thanksgiving, and December 25. Visit www.nps.gov/cwdw for details.

Fort Stevens—On July 11-12, 1864, Fort Stevens defended Washington, D.C, from Confederate attack. President Abraham Lincoln came under direct fire from enemy sharpshooters while he observed the fighting from the parapet of the fort. The Battle of Fort Stevens marks the only time Confederate forces attempted to break through the defenses of Washington. Forty Union dead were buried in an orchard on the battlefield. Dedicated by President Lincoln, their final resting place is now known as Battleground National Cemetery. The National Park Service manages both the fort and the cemetery.

Fort Marcy—Virginia joined the Confederacy on May 23, 1861, after years of political battles over economic interests, states' rights, and slavery. On September 24, 1861, the Union Army seized strategic locations in enemy territory to protect Chain Bridge on the Potomac River. Fort Marcy and its sister defense, Fort Ethan Allen (maintained by Arlington County), provided an effective deterrent against Confederate attack. Preserved within the National Park System, earthworks remain visible at Fort Marcy today.

President Lincoln's Cottage—This peaceful haven on the grounds of the U.S. Soldiers' and Airmen's Home served as President Lincoln's residence for a quarter of his time in office. Traveling to and from the White House by horse or carriage, Lincoln often encountered citizens, soldiers, and former slaves along the way. From here the President and Mrs. Lincoln traveled two miles to observe the Battle of Fort Stevens. The National Trust for Historic Preservation now administers the site and offers tours and other visitor services.

Neighboring Tensions—Before the Civil War, slavery was legal in 15 states of the Union. Maryland, which allowed slavery and was a southern sympathizing state, did not secede from the Union. This position increased tensions with Washington, D.C, when President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. Delivered on January 1, 1863, the proclamation freed slaves in states that rebelled against the United States. Slavery was not declared illegal in Maryland until November 1, 1864.

Fort Ward—The Union Army began building Fort Ward in July 1861, shortly after being defeated in the first major land battle of the Civil War at Manassas. Administered by the city of Alexandria, Virginia, Fort Ward Museum and Historic Site features preserved, restored, and reconstructed earthworks, as well as exhibits, tours, and living history activities.

Fort Dupont—Built in 1861-1862 to guard the eastern approaches to Washington, Fort Dupont remained ready for battle, although enemy attacks never occurred east of the Anacostia River. Earthworks are still visible within Fort Dupont Park, one of Washington's largest parks. Summer concerts, picnicking, and nearly 400 acres of forest now draw visitors to this National Park Service location.

Fort Foote—Built between 1863-1865, Fort Foote guarded the Potomac River approach to Washington from invasion by Confederate forces. Earthen walls 20-feet thick made this fortification more resistant to naval bombardment than aging Fort Washington, another National Park Service location seven miles to the south. Two 15-inch Rodman cannons remain poised over the Potomac at Fort Foote for visitors to enjoy today.

Note: Not all forts and batteries exist today or are publicly accessible. The fort symbols shown represent the general location of historic earthen fortifications and batteries of the Civil War Defenses of Washington. To learn more about the defenses of Washington, including directions to sites managed by the National Park Service and links to other publicly managed sites, visit www.nps.gov/cwdw.

Safety and Stewardship

You play an important role in history when you visit the Civil War Defenses of Washington with stewardship in mind. For your safety and the preservation of fort structures, do not climb on earthworks—some may be unstable. Plants and trees keep the earthworks from eroding, so leave them undisturbed. All natural and cultural objects are protected by law. Leave rocks, animals, and wildflowers in place. Keep dogs on a leash and stay on established trails. Learn to identify and avoid poison ivy. Dial 911 for emergencies.

Related Sites to Visit

Battleground National Cemetery, administered by the National Park Service, is located one-half mile north of Fort Stevens on Georgia Avenue. Interred at the cemetery dedicated by President Abraham Lincoln are the remains of Union soldiers who fought and died in the 1864 Battle of Fort Stevens. Fort Ward Museum and Historic Site, managed by the city of Alexandria, Virginia, maintains a collection of Civil War artifacts and offers public programs. Civil War earthworks are preserved at Fort C. F. Smith and Fort Ethan Allen in Arlington County, Virginia.

Source: NPS Brochure (2010)

| For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

Battleground National Cemetery (May 1982)

Civil War Defenses of Washington, D.C.: A Cultural Landscape Inventory (Jacqui Handly, September 1996)

Cultural Landscape Report: Battleground National Cemetery (Michael Commisso, May 2014)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory: Battleground National Cemetery, Rock Creek Park (2010)

Cultural Landscapes Inventory: Battleground National Cemetery, Rock Creek Park (2018)

Cultural Landcapes Inventory: Fort Chaplin (2017)

Deeply Rooted: Trees at the Foundation of America's Environmental History UERLA History Report (Abby Murphy, 2023)

Draft Management Plan: Fort Circle Parks, Washington, D.C. (October 2001)

Final Management Plan: Fort Circle Parks, Washington, D.C. (September 2004)

Foundation Document Overview, Civil War Defenses of Washington, District of Columbia-Maryland (December 2016)

Long-Range Interpretive Plan, Civil War Defenses of Washington (February 2012)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Battleground National Cemetery (Barry Mackintosh, February 15, 1980)

Civil War Fort Sites (Helen Dillon, November 1972)

Fort Circle (James Dillon, July 30, 1976)

"On the Fort": The Fort Reno Community of Washington, DC, 1861-1951 (Brian Taylor, November 2021)

The Civil War Defenses of Washington, Parts I and II: A Historic Resources Study (CEHP, Inc., 2005)

The Defenses of Washington, 1861-1865 (Stanley W. McClure, reprint 1961)

cwdw/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025