|

Dayton Aviation

What Dreams We Have The Wright Brothers and Their Hometown of Dayton, Ohio |

|

Chapter 12

Preservation Efforts And Memorialization

Throughout the lives of the Wright brothers, Daytonians were slow to acknowledge their achievements. Beginning with the lack of response from the local newspapers at the news of the first flight in December 1903, the town set a precedent; they needed proof before they would believe Wilbur and Orville Wright had conquered the problem of human flight. Throughout the brothers' experiments at Huffman Prairie Flying Field in 1904 and 1905, comments about the "activities" out near Simms Station were never investigated. It was not until Wilbur and Orville conducted demonstration flights in France and the United States in 1908 that Dayton, along with the rest of the world, embraced the Wright brothers. The Homecoming Celebration for the Wright brothers in 1909 was the first time that the brothers' hometown acknowledged their success. While both Wilbur and Orville were living, the city focused on celebrations and personal appearances in recognizing the achievements of the brothers.

After Wilbur's death in 1912, Daytonians began discussing a memorial to the Wright brothers, the most internationally recognized residents of their city. Other Dayton residents had invented various items that helped bring on the industrial age, but the airplane was the one invention at the turn of the twentieth century that received the greatest world-wide recognition. The citizens of Dayton wished to honor their famous residents, but the concept of a memorial was discussed for several decades before anything was built. While Dayton leaders wanted to honor the Wright brothers, they did little to preserve any buildings related to the invention of the airplane, choosing instead to focus on memorialization. It was not until 1980 that efforts began to preserve Wright-related buildings as well as memorializing the brothers.

One of the first and largest plans to memorialize the brothers was developed in 1912 by a committee of Dayton citizens who planned a memorial science museum honoring the Wrights. The architectural firm of Pretzinger and Musselman drew up conceptual plans for the museum at the site of Simms Station and Huffman Prairie Flying Field. The planners called for a museum to be a monument to the genius of the Wright brothers and an inspiration to visitors. They intended the exhibits to reflect scientific knowledge and to encourage scientific investigations. For some unknown reason, the project was dropped shortly after it was proposed. [1]

Another group simultaneously developing plans for a memorial was J. Sprigg McMahon's committee. Its membership included Frank B. Hale, E.C. Estabrook, and Oscar J. Needham from the Dayton Aeroplane Club and influential members of the community, such as Edward A. Deeds, John H. Patterson, P.D. Schenck, Governor James M. Cox, and Edward Philipps. The group, originally consisting of forty individuals, formed in 1910 to develop a proposal for a Wright brothers memorial. The committee grew from the Dayton Aeroplane Club, established in 1909 to commemorate the Wrights along with several other purposes. No decisions were made regarding a suitable memorial and the idea languished. Upon Wilbur's death in 1912, the committee reformed and began to actively discuss a memorial. [2]

A sub-committee of five individuals, headed by Judge C.W. Dustin, spearheaded the efforts of McMahon's committee. The initial plans called for two large columns from Athens, Greece, to be placed along Huffman Avenue where they would be visible from both the railroad trains and the traction cars. Other ideas included placing a large boulder at Huffman Prairie Flying Field, but some members of the committee felt that the memorial should be more elaborate, and include a tribute to the Wright brothers within the city boundaries. [3]

The committee eventually decided to erect two columns at the Huffman Prairie Flying Field as the first step to memorialize the Wright brothers. In their simplicity, it was felt, the columns would reflect the unassuming natures and modesty of the two brothers. In the second phase, a larger and more elaborate monument would be constructed within the city of Dayton. The committee consulted artists in both Europe and the United States about a larger monument and developed a conceptual idea of an arch of marble or granite reminiscent of Roman architecture. [4]

After developing plans, the committee was officially named the Wright Memorial Commission and incorporated in the state of Ohio on February 26, 1913. The six people who signed the incorporation papers were A.M. Kittredge, Edward A. Deeds, John C. Eberhardt, Frederick H. Rike, Edward E. Burkhardt, and O.B. Brown, who, along with Frank T. Huffman, were also the first trustees. The expressed purpose of the committee was,

commemorating the achievements of Wilbur and Orville Wright in the science of aviation, by the construction and maintenance of a memorial park to contain an appropriate sculptural figure in bronze, placed on the spot where man conquered the air by the first flight in a complete circle in a heavier than air machine, made September 1904, by the Wright Brothers. [5]

On February 27, 1913, the commission signed an agreement with the sculptor Gutzon Borglum to "make and deliver to the owners one heroic statue symbolizing 'The First Flight of Man.'" The agreement specified, "The statue shall be placed upon a granite boulder and secured in the best possible manner. It shall be cast in standard bronze, of one continuous and simple piece without seams. There shall also be an inscription placed upon the granite boulder giving such dates and other information as the owners may desire." The work was to be completed in time for the statue to be unveiled on September 20, 1913. [6]

Borglum was a fitting choice as the sculptor. He helped found the New York Aero Club, was a member of the Aero Club of America, and chaired the committee that created the medal given by the New York Aero Club to Wilbur. Additionally, Borglum attended Orville's demonstration flight at Fort Myer on September 16, 1908. During one flight at the end of the day, Borglum suggested placing a man on the roof of the stable, which Orville flew over with each loop he made of the field, to mark the minutes in the air. Orville was anxious to stay aloft for an hour, but the sky was growing dark. With Borglum's method of timekeeping, Orville would know exactly when an hour flight was achieved and not have to risk making a shorter flight or flying in darkness. [7]

After speaking to Borglum about the project, L.E. Olwell found that the sculptor was "one of the men in the east who is a pioneer as far as interest in aviation is concerned. For this reason, he would be, in my judgement, the best man in the country to undertake the work. He has a great deal of personal feeling in the matter, and at the same time is known as the best man in his work in America today." [8]

The Wright Memorial Committee also contacted the landscape architecture firm Olmsted Brothers in regards to planning "a suitable enclosure and approaches to this marker [that Borglum was designing]." The committee had retained one acre at the Huffman Prairie Flying Field from Torrence Huffman for the location of the memorial. In describing the project, the commission included the fact that a flag pole would be erected near Borglum's sculpture. They requested that Olmsted Brothers submit a plan that would complement the memorial and not cost much money but be in good taste. [9]

The landscape architecture firm, Olmsted Brothers, operated from 1857 to 1950. Founded by Frederick Law Olmsted and later operated by his sons, John C. Olmsted and Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr., the firm conducted over 5,000 landscape architecture projects in forty-five states, the District of Columbia, and Canada. Except for Boston, Massachusetts, and New York, New York, Dayton has the highest number of Olmsted designs in the United States. The Olmsteds were involved in 274 designs in Ohio; 151 of these were in the Dayton area. Forty-seven of these designs were built. [10]

The plans to erect the memorial at the Huffman Prairie Flying Field led to the idea to rename Simms Station, the interurban railway stop at Huffman Prairie Flying Field, after the Wright brothers and to construct a waiting station at the stop. The suggested names included Wright Brothers Field or Wrights. The president of the Ohio Electric Railway, W. Kelsey Schoeph, responded favorably to the suggested name change, favoring naming the station Wrights. The only hindrance was he had already promised that the station would be named after the Huffman family who owned the adjacent property. Ultimately, the Huffmans agreed to naming the station after the Wright brothers, and on April 1, 1913, the station's name was to be changed to Wright Station. [11]

The intentions of the Wright Memorial Commission were indefinitely put on hold because of the devastating flood of 1913. The attention of the trustees and commission members was focused on recovery and future flood control efforts, and the construction of a Wright brothers memorial would have to be postponed. A.M. Kittredge, the president of the commission, telegraphed Borglum on March 30 to inform him that, due to the flood, all work on the memorial must cease until a later date. In 1920, the Wright Memorial Commission was dissolved since their objective of erecting a memorial to the Wright brothers could not be met. The flood control measures, eventually carried out, called for a reservoir behind the Huffman Dam that would inundate the Huffman Prairie Flying Field during a flood. [12]

The idea of a memorial was resurrected in 1922, and the Wilbur and Orville Wright Memorial Commission was re-established. The new commission had the same objective and trustees as the Wright Memorial Commission. Edward A. Deeds served as president. At the same time, The Dayton Air Service Incorporated Committee was formed. It sought to retain the United States Army Air Service Experiment Station in Dayton as well as erect a memorial to the Wright brothers. They also began to solicit funds to purchase a site and build a Wright brothers memorial, and the two commissions worked together to establish a memorial to Wilbur and Orville. [13]

While Daytonians discussed erecting a memorial to Wilbur and Orville, people in North Carolina planned for commemorating the site of the first free, controlled, and sustained flight in a power-driven, heavier-thanair machine. A local effort instigated by W.O. Saunders, the editor of the Elizabeth City Independent, wanted special recognition for the Kill Devil Hills site. Saunders advocated economic development of the Outer Banks of North Carolina and included a memorial to the Wright brothers' experiments and flights in his idea. [14]

Several national figures soon joined the North Carolina effort for a Wright brothers memorial, and on December 17, 1926, U.S. Representative Lindsay Warren of North Carolina introduced a bill in Congress for a Wright memorial. Senator Hiram Bingham of Connecticut, a former World War I aviator, introduced a similar bill in the U.S. Senate the same day. The act passed both houses of Congress, and President Coolidge signed the bill on March 2, 1927. [15]

The first step in the realization of the Wright brothers memorial occurred on December 17, 1928, with the dedication of a granite marker placed at the approximate location of the liftoff twenty-five years earlier. At the same ceremony, the cornerstone of the monument, as yet to be designed, was placed. The architectural firm Rodgers and Poor won a design contest. Construction for the monument began in 1930, and it was dedicated on November 19, 1932. Initially under the oversight of the War Department, the site, now Wright Brothers National Memorial, was transferred to the National Park Service in 1933. [16]

The erection of the memorial in North Carolina caused some discussion in Dayton as to the location. The following commentary appeared in the Dayton magazine Slipstream in November 1927:

We wonder if those who voted for the measure knew that Kill Devil Hills were inaccessible to the motoring public? We wonder if they knew it would require a huge subscription of funds to build roads and a great bridge in order that those few who happen to travel in this out of the way tract could get to the memorial? Furthermore, we wonder if they knew that citizens of Dayton, Ohio, the home town of the Wright brothers had already bought and set aside a tract of ground on the very spot where the Wrights first assembled their flying machine... Certainly it is in Dayton that a Wright Memorial should be located. [17]

The article advocated a museum, instead of a memorial, where the 1903 airplane would be displayed. While this opinion received approval, critique, and further comments, the editor of the magazine noted that the majority of the readers responding to his editorial agreed with his opinion. [18]

The initial efforts to honor the Wright brothers focused on memorials. The first effort to preserve a Wright-related building was instigated by Henry Ford. In the 1920s, Ford began assembling historic buildings in a museum in Dearborn, Michigan, named Greenfield Village. Established when the automobile began to change the landscape of America, Greenfield Village's mission was to preserve buildings from an earlier era. At the same time Ford started Greenfield Village, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., established Williamsburg in Virginia. While on the surface these two museums seemed similar, the contents were different. Rockefeller focused on reconstructing an eighteenth century town, while Ford collected structures associated with notable figures in American history. [19]

Ford purchased, relocated, and restored historic structures at Greenfield Village. Some of his first acquisitions were the Ford homestead and Thomas Edison's laboratory. In 1938 both the 1127 West Third Street building and the Wright home at 7 Hawthorne Street were added to the buildings displayed at Greenfield Village. Ford's acquisition of these two buildings came about from efforts of William E. Scripps, publisher of The Detroit News and president of the Early Birds. The Early Birds was a group of pioneer airplane pilots who flew prior to 1916. The group felt that Ford possessed the necessary resources to preserve the story of the Wright brothers' invention of the airplane. [20]

Initially, the Early Birds focused upon the return of the Wrights' 1903 airplane from England. Ford was interested in making the 1903 airplane the centerpiece of an aircraft exhibit. The Early Birds did not conceive of the idea, for Ford had contacted Orville in 1925 as to the availability of the 1903 plane for exhibit at his new museum. Nothing resulted from Ford's initial interest in obtaining the first airplane, and the Early Birds renewed the efforts to acquire artifacts to illustrate the conception of the first successful airplane. James V. Piersol, a reporter from The Detroit News, represented Henry Ford and his son Edsel at an initial meeting with Orville in December 1935. At that time, Orville explained the feud with the Smithsonian Institution and his determination that the plane would not return to the United States until the situation was resolved to his satisfaction. [21]

In response to the improbability that the airplane would return to the United States in the near future, Piersol shared with Orville that Ford was also interested in preserving the building at 1127 West Third Street, the balances from the wind tunnel tests, and any other artifacts that Orville felt were valuable in telling the story of the discovery of human flight. Orville was interested in Piersol's proposal that at least some of the artifacts, and maybe the last bicycle shop, be acquired by Henry Ford and displayed at Greenfield Village. In fact, Orville spent the evening after meeting with Piersol, gathering items that might be of interest to the museum. [22]

Following the meeting, Edsel Ford contacted Orville about the Fords' interest in purchasing the building at 1127 West Third Street and reconstructing it at Greenfield Village. Keeping the pending deal confidential, Orville worked with the Fords and Piersol to arrange the purchase of 1127 West Third Street from Charles Webbert. During negotiations and discussions with Orville, Piersol was also made aware of the Wright home at 7 Hawthorne Street. Being the birthplace of Orville, where Wilbur died, and where the brothers resided during their experiments, Ford immediately became interested in also acquiring the family home. [23]

Henry Ford purchased the Webbert building at 1127 West Third Street on July 2, 1936, from Charles Webbert for $13,000 with plans to move the building to Greenfield Village. In October 1936, Henry Ford and his son Edsel traveled to Dayton to see the Wright buildings and meet with Orville. The Fords were accompanied by Fred Black, who was in charge of the museum collection, and William Scripps. The group first dined at Hawthorn Hill along with James Cox, Captain Lewis Rock, and Lorin Wright. After lunch, the group inspected the building at 1127 West Third Street and then stopped to see the Wright home at 7 Hawthorne Street. [24]

Negotiations for purchase of the Wright home from Lottie Jones were soon underway. By November, Orville had assisted the Fords in negotiating a deal to purchase 7 Hawthorne Street for $4,100. The two buildings were moved piece by piece to Dearborn where they were reconstructed to the exact specifications of the original construction. In fact, Ford was intent on reassembling the buildings as they were in Dayton, and he moved five dump truck loads of soil from the 7 Hawthorne Street lot, totaling almost twenty tons, so that the home continued to stand on Dayton soil. [25]

In order to reconstruct the buildings as they appeared at the time of the Wrights' occupation, the museum worked with Orville to record his memories as well as assist in gathering articles. In addition, to facilitate with the reconstruction of the bicycle shop, Charlie Taylor was hired. Taylor had been living in California and at the time was working in the toolroom at North American Aviation in Los Angeles. The two relocated buildings were dedicated at Greenfield Village on April 16, 1938, the seventyfirst anniversary of Wilbur's birthday. [26]

THE WRIGHT FAMILY HOME AND THE LAST BICYCLE SHOP AT GREENFIELD VILLAGE AND HENRY FORD MUSEUM, C. 1938. (Courtesy of Wright State University, Special Collections and Archives) |

Daytonians' response to the relocation of the Wright buildings to Greenfield Village ranged from approval to shock, but the purchase of the bicycle shop at 1127 West Third Street also brought renewed attention to the hometown boys who invented the airplane. Many individuals interviewed for newspaper articles expressed disappointment that the buildings were lost to Dayton, but they were proud that they were incorporated into Ford's museum that honored the great people in American history. With the loss of the Wrights' bicycle shop building and home, Daytonians once again felt a need to honor the brothers. The plans that were waylaid by the 1913 flood once again began to surface. [27]

One of the first ideas to resurface was the construction of a Science Museum in the Wrights' honor. First proposed in 1912, the Aviation Committee of the Dayton Chamber of Commerce resurrected the project. Altering the original plans, the committee considered building at the then vacant lot at 1127 West Third Street instead of the Huffman Prairie Flying Field. The contents of the museum would focus on aviation both on a local and national level as well as having rooms available for meetings. [28]

Tasked with preserving the aviation history in Dayton related to the Wright brothers, the Aviation Committee also suggested several other projects that would memorialize the Wright brothers. The various ideas included placing a bronze plaque in the sidewalk at 1127 West Third Street and having the state of Ohio take over the .52-acre tract located on Huffman Prairie Flying Field set aside by The Dayton Air Service Incorporated Committee for a memorial. The latter location was chosen because it was the starting point of Wilbur's September 20, 1904, flight when he flew the first circle in an airplane. While the committee, which had been raising funds since its inception in 1922, had ample funds to construct a memorial, the Aviation Committee felt that if the state took over the property, federal funds might be obtained to assist with the construction of a Wright brothers memorial. [29]

One of the committee's main concerns was placing a permanent marker at the site of the 1910 hangar at Huffman Prairie Flying Field. By 1936, when the Aviation Committee was formed, the hangar had deteriorated. Several years prior, the Dayton Air Service Incorporated Committee spent three hundred dollars to repair the roof and paint the exterior. By 1936, little of this was visible, and no further plans to preserve the building were discussed. In their plans to memorialize the Wright brothers, the Dayton Air Service Incorporated Committee, in agreement with the Aviation Committee, planned to demolish the hangar and erect a marker. While the hangar was demolished sometime between 1939 and 1943, no marker was erected at the site. [30]

While discussions resumed as to how to memorialize the Wright brothers, the work of the Dayton Air Service Incorporated Committee garnered attention. Making plans since their inception in 1922, the committee owned twenty acres of land received from the Miami Conservancy District, overlooking Huffman Prairie Flying Field. [31]

As the plans moved forward, the Dayton Air Service Incorporated Committee determined if they returned the hilltop to the Miami Conservancy District, a public corporation, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) could assist with the grading of the site and construction of roads and parking areas. As a result, the tract was deeded to the Miami Conservancy District on June 1, 1938. [32]

The Wilbur and Orville Wright Memorial Commission, which took over the Wright brothers memorial project from the Dayton Air Service Incorporated Committee, spearheaded the plans to build a memorial. The commission, headed by Deeds, reached an agreement with the Miami Conservancy District that it would build and maintain the memorial using the $25,000 raised by the commission. The balance of the cost, not to exceed $30,000, would be obtained from a benefit assessment. [33]

In 1937, the CCC camp landscape architect submitted a proposal for the Wright Memorial. This plan was rejected, and the Olmsted Brothers, whom Deeds contacted back in 1912, were contacted again about designing a memorial site. Olmsted Brothers presented a preliminary plan for the Wright Memorial on April 26, 1938. Two representatives from Olmsted Brothers presented the plan to the directors of the Wilbur and Orville Wright Memorial Commission on October 7. At this time the directors unanimously approved the plan. In addition, they all accepted a motion by Mr. Rike to name the memorial, Wright Brothers Hill. [34]

The plan included a shaft in the middle of the design, and this feature may be attributed to Gutzon Borglum, who like the Olmsted Brothers, was retained in 1913. Borglum's original concept for a sculpture at the memorial was a winged figure poised for flight from a boulder. On February 14, 1913, Percy R. Jones, a representative from Olmsted Brothers, met with Borglum in New York. At this meeting, the two reached the decision that in consideration of the surrounding landscape, Borglum would design a monolith. The shaft would rest on a concrete foundation. The records from this meeting imply that the winged figure may have been placed on top of the shaft. There is no record of any involvement in the project by Borglum when the project was resumed in 1937. If he designed the shaft that is the focal point of the constructed monument, the design dates from this 1913 meeting. [35]

Construction plans called for the CCC to furnish the unskilled labor and much of the needed construction equipment while the Miami Conservancy District and the Wilbur and Orville Wright Memorial Commission furnished the skilled labor. Since the CCC carried out a portion of the construction of the memorial, the National Park Service, who directed the CCC forces, needed to approve the design. Once the design was approved, the CCC began construction at the site. [36]

The CCC forces that worked on Wright Brothers Hill were from the African American Camp Miami, Ohio Number 20, located in Vandalia that was established on August 14, 1935. The majority of the camp's work was focused on developing the recreational areas above the Taylorsville and Englewood Dams. The CCC workforce conducted grading and paving, and they dug drainage ditches and set the base of the memorial at Wright Brothers Hill. In addition to the CCC work, the Siebenthaler Company provided the landscape plantings and the tablet on the shaft was designed by Gorham. [37]

The design consisted of two prominent north-south and east-west axes. A seventeen-foot shaft constructed of pink North Carolina granite surrounded by three steps dominates the center of the memorial. Along one of the walls that encircle the shaft are four bronze plaques that discuss significant aspects of the memorial and the Wright brothers. The subjects of the four plaques are the Huffman Prairie Flying Field, the names of early aviators, the contribution of Wright Field, and the prehistoric mounds located on the memorial grounds. [38]

During the construction of Wright Brothers Hill, Adena Mounds on the western edge of the site were discovered. Dr. Shetrone, head of the Archaeology Department of Ohio State University, visited the site to survey the mounds. Shetrone scratched the surface of one of the smaller mounds and found bones and teeth just below the surface. Based on this discovery, the prehistoric mounds were left undisturbed, and a tablet was placed at the memorial describing the mounds' significance. [39]

DESIGN FOR WRIGHT MEMORIAL BY OLMSTED BROTHERS' LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTS. (Courtesy of Wright State University, Special Collections and Archives) |

From Wright Brothers Hill there is an excellent view of the Huffman Dam, the Mad River, and Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. At the time of construction, the Huffman Prairie Flying Field was part of Wright Field and the site was inaccessible to visitors. To mark the flying field, a small pylon was constructed on the Huffman Prairie Flying Field at the site set aside earlier by the Dayton Air Service Incorporated Committee. This pylon was to visually mark the location of the flying field from the memorial. [40]

Wright Brothers Hill was dedicated on August 19, 1940, Orville's sixt-yninth birthday. Orville and early aviators such as Major General Hap Arnold, Walter Brookins, and Kenneth Whiting, attended the ceremony. The ceremony began with an invocation by Bishop A.R. Clippenger and then Major General Hap Arnold spoke for the Army and Captain Kenneth Whiting for the Navy. The monument was unveiled by Leontine Jameson, the daughter of Leontine and John Jameson, and Marianne Miller, the daughter of Ivonette and Harold Miller, both grand-daughters of Lorin Wright. The ceremony concluded with an address by former Ohio Governor James M. Cox. [41]

Shortly after the dedication of the Wright Brothers Memorial, discussions arose as to the disposition of the former location of the Wright family home. In 1941, the Fords, who still held title to the vacant lot at 7 Hawthorne Street, began to consider how to dispose of the property. When Orville was in Dearborn in June, Fred Black asked for any suggestions of to whom to deed the property. Orville spoke to the secretary of the African American Y.M.C.A., located on West Fifth Street, to see if they could use the lot. Additionally, on November 25, 1941, the Fords offered to deed the lot to the city. They proposed giving the lot to the city and paying all delinquent taxes, if the city would erect a marker at the site. [42]

The city forwarded the proposal to the City Plan Board for consideration who then referred it to the Dayton Historical Society. [43] The Dayton Historical Society decided not to enter into the decision making process, feeling that Orville could better assist in arriving at a satisfactory solution. With the historical society removing itself from the decision making process, the City Plan Board, with the sole authority to comment on Ford's proposal, concluded that the city of Dayton should not accept the lot and recommended, in agreement with Orville, that the lot be transferred to the Fifth Street Branch of the Y.M.C.A. They believed that the Y.M.C.A. could use the lot for recreational purposes. This offer ultimately fell through, the lot was sold, and it is now privately owned. [44]

From 1934 to 1946, Orville served as a member of the Oakwood Library board. For eleven of those twelve years, he was the vice president with the agreement that he would never have to chair a board meeting in the absence of the president. In 1939 the new library building at 1776 Far Hills Avenue was named in honor of Wilbur, Orville, and Katharine Wright. [45]

After Orville's death in 1948, the citizens of Dayton once again focused on their city's link to the birth of aviation. In the year following his death, many sites throughout the region were dedicated in honor of the Wright brothers. Some of the projects were planned prior to Orville's death but not completed until later. The most notable of these was the restoration of the Wright Flyer III. This was the first instance that a resource related to the Wright brothers was preserved instead of a memorial constructed. Prior to this, Daytonians had made no effort to preserve any of the buildings or airplanes in Dayton related to the Wright brothers and their invention of the airplane. They had honored their famous residents through memorials and ceremonies, but no preservation efforts were initiated.

Orville's friend, Edward Deeds, now the chairman of the board of The National Cash Register Company, was responsible for this first preservation effort in Dayton related to the Wright brothers. Deeds was building a park to commemorate the role the Miami Valley played in the evolution of transportation, and he believed the achievements of Wilbur and Orville Wright would make a good focal point for the museum. Deeds presented his idea to Orville and inquired about the possibility of one of the Wright brothers' earlier planes for exhibit, and Orville suggested that Deeds construct a replica of the 1903 airplane. [46]

Orville gave permission to the Science Museum in London to create a set of drawings and a replica of the flyer before he officially requested they return the plane to the United States. The original 1903 airplane would be displayed at the Smithsonian Institution, but Orville felt that another exact replica could be made in England for exhibit at Deeds' museum, named Carillon Historical Park. [47]

A few days later, Orville approached Deeds with another idea. He believed that there were enough original parts of the 1905 Wright Flyer III that the airplane could be restored and exhibited at the park. Orville was enthusiastic about including the Wright Flyer III at Carillon Park, for the first practical airplane had much more significance to Dayton. It flew at Huffman Prairie Flying Field and played a large role in aviation history. [48]

The parts of the Wright Flyer III were scattered between Orville's laboratory, homes in Kitty Hawk, and the Berkshire Museum in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. The Wright Flyer III was reconfigured in 1908 and flown at Kitty Hawk prior to the demonstration flights in France and Ft. Myer. When the experiments were completed, the airframe was abandoned in Kitty Hawk, and the engine, chain guards, propellers, and other items were shipped back to Dayton. In 1911, Zenas Crane, a wealthy Massachusetts paper manufacturer who established the Berkshire Museum, wrote to Wilbur and Orville requesting an airplane or glider that could be exhibited in the museum. The Wright brothers responded that there were no gliders that had been preserved, but the various parts of the 1905 airplane could probably be obtained by contacting the Kill Devil Hills Life Saving Station in Kitty Hawk. [49]

Along with the various parts of the Wright Flyer III in Kitty Hawk was the 1911 glider that Orville flew in Kitty Hawk earlier in 1911. Crane acquired all of the remaining parts of the Wright Flyer III and the 1911 glider with the intent of reassembling the machines, but he had little knowledge of Wright airplanes and no idea how to begin reconstructing the machines. He began with the 1911 glider, having his workmen configure the parts into something that resembled the 1902 glider. When Orville saw the resulting glider, he refused to allow the museum to exhibit the machine. [50]

Realizing the mistakes, Crane requested Orville's assistance in reconstructing the 1905 Wright Flyer III. Orville was convinced that the workmen at the museum should not attempt to rebuild the plane, so he convinced Crane to delay the work. Orville was also hesitant to participate in the project. For the next thirty years, Crane and others continued to ask for Orville's help as an advisor in rebuilding the 1905 airplane, but Orville continually denied their request. When Deeds was looking for an airplane to exhibit at Carillon Historical Park, nothing had been done with the Wright Flyer III parts that Crane acquired in 1911. [51]

Deeds' request provided Orville an opportunity to guarantee that the Wright Flyer III was correctly reassembled. The first step was to obtain the parts acquired by Zenas Crane for the Berkshire Museum. Carl Beust, the head of The National Cash Register Company Patent Department, met with the director of the museum and found him to be agreeable to sending the parts of the airplane to Dayton. Beust also met with representatives from the museum at Edenton, North Carolina, that also had parts of the 1905 airplane. They too were amenable to sending the parts to Dayton to be used in the restoration of the airplane. Beust succeeded in gathering all of the parts in Dayton by the end of 1947. [52]

All these known parts of the Wright Flyer III represented somewhere between sixty and eighty-five percent of the original plane. Deeds retained Harvey Geyer, who worked for the Wright brothers from 1910 to 1912, to oversee the reconstruction effort, and provided The National Cash Register Company building as a workshop to restore the flyer. Orville took an active effort in the rebuilding of the plane until his first heart attack in 1947. He provided all the necessary technical information and necessary measurement needed to complete the reconstruction. [53]

While the reconstruction of the airplane was underway, a building, named Wright Hall, was constructed, with Orville's input, to exhibit the plane. The brick building was constructed for the sole intention of displaying the airplane, so the plane rests in a three foot depression on the ground level that allows for visitors to view the plane from above. Both Wright Hall and the Wright Flyer III were dedicated in June 1950.

Along with the restoration of the Wright Flyer III, Deeds was instrumental in The National Cash Register Company purchasing Hawthorn Hill after Orville's death. Discussions surfaced in Dayton immediately after Orville's death as to the future of Hawthorn Hill. One of the first actions taken was to submit a proposal in Congress for the United States government to assume ownership of the home and maintain it as a museum. No action was taken by Congress, for the legislators decided not to fund any additional national memorials. An additional proposal called for the city of Oakwood to purchase the home, but the Oakwood City Council immediately dismissed the idea due to the necessity for a bond issue. [54]

The Wright family members who inherited the home from Orville could not afford the costs to maintain it and hoped to sell it to a purchaser who would preserve it as Orville Wright's home. Finally, when no ideas materialized, Harold Miller, the co-executor of Orville's estate, listed the house with a real estate agent. The day the for sale sign was placed in the yard, The National Cash Register Company arranged to purchase the home for $75,000. They planned to use the home as a guest house for international corporate visitors. [55]

Soon after Orville's death, an abundance of proposals were presented that would honor the Wright brothers. Many of these ideas were never carried out, but the quantity of the proposals set forth signified the great desire of Daytonians to do something. One of the first proposals was for a Wright Avenue or other appropriately named street in Dayton. Positive feedback was received to a Dayton Daily News suggestion that the name of Main Street be changed to honor Wilbur and Orville. A follow-up article noted that seventy-five percent of the letters received at the newspaper offices in response to the proposal were in favor of changing the street name, although some respondents suggested changing the name of an alternative street. One of the suggested streets to be named after the Wright brothers was Third Street; stretching from Wright Field to the National Military Home, the road passed the site of several Wright brothers' bicycle and printing shops. [56]

WRIGHT HALL UNDER CONSTRUCTION, AUGUST 1948. (Courtesy of NCR Archives at Montgomery County Historical Society) |

At a Rotary Club program that included intimate sketches of Orville, who was an honorary member of the Dayton club, it was proposed that Springfield Street be widened and become a memorial route. The idea, presented by Paul Ackerman, included the idea of a memorial arch at the intersection of Springfield and East Third Street. Springfield Street was chosen as the possible memorial route for it leads from Dayton to both Wright Field and the Huffman Prairie Flying Field. [57]

An above ground skyway was immediately successful. The Civil Aeronautics Administration approved the "Wright Way," a forty mile wide memorial skyway that stretched from Los Angeles, California, to Washington, D.C. It was the first coast-to-coast air-marked route. At each city and town along the route, airmarkings noted the longitude and latitude and compass heading. In addition, an arrow pointed to the nearest airport. [58]

Reacting almost four decades after the last Wright brothers' bicycle shop was relocated to Greenfield Village, the Dayton Chamber of Commerce began campaigning for the construction of a replica of the building at Carillon Historical Park. The idea of a reconstruction of the bicycle shop was proposed after several failed attempts to return the original building to Dayton. The project was announced in 1965, but ground was not broken for the exact replica until 1970. [59]

One of the first efforts to preserve a Wright-related building occurred in 1972 when Orville's laboratory building was threatened with demolition. The property owners, Standard Oil Company of Ohio, planned to raze the building and erect a gas station at the corner of West Third and Broadway Streets. Benjamin D. Mellinger, chairman of the preservation committee of the Montgomery County Historical Society, led a campaign to save the building and relocate it in downtown Dayton near the Dayton Exhibition Center. By 1973, this idea had fallen by the wayside due to the extreme expense. [60]

Recognizing the significance of the building it planned to tear down, the Standard Oil Company of Ohio offered the building and $1,000 to anyone who would move the historic laboratory to another location. While the oil company worked with the Dayton Chamber of Commerce, they were unable to find anyone interested in relocating the building who also had the needed financial backing to cover the costs. After delaying their plans for the construction of a gas station for several years, Standard Oil Company of Ohio demolished the laboratory in November 1976. The facade was saved and given by the company to Wright State University. [61]

Few efforts to memorialize the Wrights, after the fight to save the Wright Aeronautical Laboratory, were undertaken until 1980. Since that time the preservation of aviation related sites, especially those linked to the Wright brothers, has gained acceptance. While battles were fought to save buildings and sites, the lack of awareness that existed in previous years was gone. After becoming aware of the Miami Valley's unique aviation history, the citizens of Dayton rallied behind the efforts of Aviation Trail Incorporated and others to save and promote this heritage.

The current preservation movement grew out of a regional economic development conference held at the University of Dayton in November 1980. One of the proposals focused on the use of the region's aviation heritage to market the Miami Valley. The proposal called for the establishment of two "trails": a tourist trail that would attract visitors and a business trail to draw companies. A committee, formed to implement the plan, held its first meeting on February 25, 1981. Five months later on July 13, the enthusiastic members of this committee established the non-profit Aviation Trail Incorporated. The purpose of the organization was three fold: 1) to identify and preserve the aviation heritage of Dayton and the Miami Valley, 2) to increase the region's awareness of its place in aviation history through promotional and educational activities, and 3) to stimulate the area's economic development through aviation related capital projects. As established, the organization is governed by a Board of Trustees numbering no less than fifteen members and no more than twenty. In 1982 a Board of Advisors, with no membership limit, was also established. [62]

To date, the main focus of Aviation Trail Incorporated has been the establishment of the tourist trail, called the Aviation Trail, that consists of sites related to the aviation heritage of the region. The first project was the creation of a brochure highlighting ten sites along the Aviation Trail of most interest to the general public. Then the Dayton-Montgomery County Convention and Visitors Bureau placed signs at each site designating it as part of the trail. In addition, Mary Ann Johnson offered to research the region's aviation heritage and develop a comprehensive listing of all significant sites. [63]

Mary Ann Johnson in her research uncovered forty-five sites for the Aviation Trail, and they were explained and highlighted in the 1986 book, A Field Guide to Flight: On the Aviation Trail in Dayton, Ohio. Two of the fortyfive sites, the bicycle shop at 22 South Williams Street and the Hoover Block, were little known sites directly related to the Wright brothers' early years in West Dayton. [64]

Research revealed that these were the only two Wright-related buildings on the West Side that still stood on their same location and had minimal alterations. Both the Wright home at 7 Hawthorne Street and the last bicycle shop at 1127 West Third Street were preserved by Henry Ford at Greenfield Village, but what had happened to the other buildings? The building that contained the brothers' first printing office outside of the Wright home, 1210 West Third Street, was demolished in the 1950s and never redeveloped. Demolition was the same fate for the bicycle shop building at 1034 West Third Street. It was demolished in the early 1900s and replaced with a two-story brick commercial building. The lot remains vacant after the building was destroyed by fire. [65]

The first bicycle shop, 1005 West Third Street, was incorporated into what is now the Gem City Ice Cream Building. The original facade of the building was replaced and the structure enlarged, so that remnants of the Wright brothers' building were enclosed inside the existing structure. [66]

THE WRIGHT CYCLE COMPANY BUILDING AT 22 SOUTH WILLIAMS STREET PRIOR TO RESTORATION. (Courtesy of Aviation Trail, Inc.) |

Understanding the significance of the two remaining Wright-related buildings in their West Dayton neighborhood, Aviation Trail Incorporated decided to broaden their activities and acquire the buildings. After locating the owners and negotiating a contract, Aviation Trail Incorporated agreed to purchase 22 South Williams Street for $11,000. Since the nonprofit group did not have available funds to purchase the building, J.H. Meyer, a trustee, purchased the building in May 1982 through a private corporation he owned and agreed to hold the building until Aviation Trail Incorporated could pay for it. The organization acquired the building in June 1983 with grants from the city of Dayton and Montgomery County. [67]

Within a few weeks of the initial purchase, the trustees were surprised to discover that the city of Dayton building inspector had condemned the building. After trustees explained the historical significance of the building and their restoration plans to city officials, it was agreed that the building would be boarded up until the work began. This agreement saved 22 South Williams Street from imminent demolition as a condemned structure. [68]

With the preservation of the building secured, Aviation Trail Incorporated began to look for restoration funding. The first grant received was for $25,000 from the city of Dayton. This money allowed Aviation Trail Incorporated to contract with the historical architectural firm, Gaede-Serne-Zofcin from Cleveland, for the development of restoration plans. An 1896 photograph of the building as the Wright Cycle Company uncovered by Marlin W. Todd provided guidance for the exterior restoration work. Many volunteer hours were provided to clean out the interior of the building while other grants and donations, including a $66,500 grant from the State of Ohio, provided restoration funds. [69]

The bicycle shop opened to the public on June 25, 1988, after the majority of the exterior and first floor restoration was completed. The second floor was not restored, but was designed as a caretaker's residence. This construction was not completed until September 1993 when the space was used for offices. In May 1987, the first floor of the bicycle shop was opened on weekends and was staffed by a manager supplied by the Urban League. Visitors could view the restoration in progress and see a small interpretive display. After completion of the first floor restoration, a museum was established that emulated a traditional turn of the century bicycle shop and told the story of the Wright brothers through historic photographs and interpretive signage. At this time, Aviation Trail Incorporated hired its own manager who opened the museum on the weekends. [70]

While the restoration work began on 22 South Williams Street, the organization also turned its attention to the acquisition of the Hoover Block. In 1982, it purchased the building, as well as the neighboring Setzer building and the vacant lot between the Hoover Block and 22 South Williams Street with a loan from City-Wide Development Corporation. It planned to restore the Hoover Block and develop a museum. It envisioned displays on the Wright brothers on the first floor, office space and a reconstructed Wright & Wright printing office on the second, and the meeting hall on the third floor would have a parachute museum. Gaede-Serne-Zofcin Architects developed a master plan for the Hoover Block in the fall of 1987. This plan assessed the condition of the building and developed a strategy for its use. [71]

GRAND OPENING OF THE WRIGHT CYCLE COMPANY BUILDING, JUNE 25, 1988. (Courtesy of Aviation Trail, Inc.) |

While Aviation Trail Incorporated focused on the restoration efforts at the Wright bicycle shop and the Hoover Block, it was also aware of the significance of the Wright-Dunbar neighborhood that surrounded the two sites. Officials adopted the redevelopment of the area as a goal. In 1982 the Board of Trustees generated "Development Plan for the Wright Brothers Inner West Enterprise Zone" that identified actions to assist in revitalizing the West Dayton neighborhood. Central to the plan were specific actions for eight identified Wright related sites. The recommendations included restoring the Hoover Block and 22 South Williams Street and operating them as museums; reconstructing 1127 West Third Street, Orville's laboratory at 15 North Broadway Street, and the home at 7 Hawthorne Street; developing the vacant lot at 1034 West Third Street into a Wright memorial garden; and placing signage at 1210 and 1005 West Third Street to identify the sites' significance in the Wright brothers' story. [72]

Aviation Trail Incorporated had a grand vision for the revitalization of the Wright brothers' neighborhood, but other efforts within the neighborhood overshadowed and diverted their plan. In 1989, Gerald Sharkey, then president of Aviation Trail Incorporated, Federal Judge Walter H. Rice, and J. Bradford Tillson, publisher of the Dayton Daily News, met to discuss the future of the neighborhood. At the time, the city of Dayton was actively pursuing an urban renewal plan which demolished neglected and nuisance buildings. This committee focused on ways to preserve the historic character of the West Side neighborhood. The recommendation of this committee and positive publicity contributed to the city of Dayton's decision to alter its plan and focus on preserving the historic neighborhood. [73]

At approximately the same time, thoughts of creating a national park in Dayton based on the Wright brothers and Paul Laurence Dunbar began to surface. The United States Air Force was questioning how to preserve and present the Huffman Prairie Flying Field and Gerald Sharkey, if not all of Aviation Trail Incorporated, was questioning the future of the Wright related buildings on the West Side. Several steps taken in 1989 led toward the efforts to create a national park and the eventual designation of Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park. [74]

Sharkey, Rice, and Tillson requested that the National Park Service conduct a national historic landmark theme study. The Midwest Regional Office evaluated the forty-five sites on the Aviation Trail and prepared National Historic Landmark nominations for seven: The Wright Cycle Company building at 22 South Williams Street, Hoover Block, Wright Flyer III, Huffman Prairie Flying Field, Hawthorn Hill, The Wright Company buildings, and the Wright Seaplane Base. The Washington Office agreed to recommend The Wright Cycle Company building, Wright Flyer III, and Huffman Prairie Flying Field to the Secretary of Interior's Advisory Board for the National Park System. In April 1990, the advisory board determined that these three are sites of national significance and recommended they be designated national historic landmarks. These three sites were designated in June 1990. Additionally, the advisory board recommended that Hawthorn Hill's nomination be revised and resubmitted. Hawthorn Hill was considered eligible and designated in July 1991. [75]

At the time this study was undertaken, Sharkey, Rice, and Tillson met once again to discuss the aviation heritage unique to the Miami Valley. The meeting resulted in the formation of The 2003 Committee in the fall of 1989. [76] The purpose of this nonprofit organization was to prepare the Dayton area as the lead in the celebration of the one hundredth anniversary of flight in the year 2003, to preserve and promote Dayton's aviation heritage, and encourage economic development. While not stated in the incorporation papers, one immediate concern and purpose for The 2003 Committee was the designation of a national park. [77]

In late 1989, under the auspices of The 2003 Committee, Congressman Tony Hall requested the National Park Service initiate a study of alternatives to identify the various possibilities for preserving and interpreting Dayton's unique aviation heritage. In conjunction with the national historic landmark theme study, the alternatives study focused on The Wright Cycle Company building, Wright Flyer III, and Huffman Prairie Flying Field. In addition, it included the Hoover Block, Hawthorn Hill, the West Third Street National Register Historic District, [78] and the Paul Laurence Dunbar State Memorial. This study aided the U.S. Congress in determining if a national park should be established in Dayton. [79]

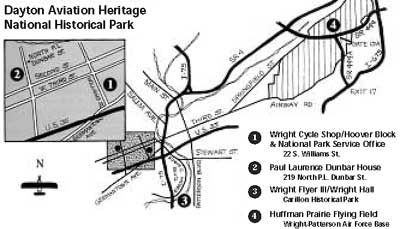

MAP SHOWING THE FOUR SITES OF DAYTON AVIATION HERITAGE NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK, 1995. (Courtesy of National Park Service) |

While the National Park Service conducted the Study of Alternatives, The 2003 Committee continued to lobby Congress for legislation creating a national park. In the eyes of those involved in the efforts, the designation of a national park was the best answer to preserving and promoting the aviation heritage of the Miami Valley. While other options were possible, such as a state or local park, the majority of efforts focused on a national park. The large lobbying efforts by interested citizens promoted the project to the Congressmen.

Eventually, after years of hard work, Congress passed the Dayton Aviation Heritage Preservation Act on October 16, 1992. This act established Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park. The park includes the Wright Cycle Company building at 22 South Williams Street, Hoover Block, Huffman Prairie Flying Field, Wright Hall and the Wright Flyer III, and the Paul Laurence Dunbar House. With the authorization of the national park, Dayton's historic places telling the story of the Wright brothers, Dayton's aviation heritage, and the life and works of Paul Laurence Dunbar received national recognition.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

daav/honious/chap12.htm

Last Updated: 18-Feb-2004