|

Dayton Aviation

What Dreams We Have The Wright Brothers and Their Hometown of Dayton, Ohio |

|

Chapter 5

Bicycles

The partnership that Wilbur and Orville developed in their printing business was the beginning of a successful merging of the two brothers' personalities. They continued to foster this relationship when they opened a bicycle repair and sales shop in 1892, and as the new business became more successful, the brothers worked together to develop their own brand of bicycle. Through the repair and manufacture of bicycles, Wilbur and Orville honed their mechanical skills and acquired a greater understanding of the mechanics of a bicycle. While they had been feeling unchallenged in the printing business, the bicycle business provided the brothers with new problems to tackle and skills to hone.

While Wilbur and Orville put much of their time into the bicycle business, their father continued to focus on the battle within the United Brethren Church between the Radicals and Liberals. The entire Wright family rallied to their father's support, and when necessary they pitched in to help with his effort on behalf of the conservative Radicals. In fact, after their bicycle business, Milton's church business took up much of the brothers' time, especially Wilbur's. Milton's central role in the church's rift emphasized the importance of family to his children. While both Milton and his wife, Susan, had instilled the importance of family in their children, nothing illustrated this to the extent of the division in the church. Church historians portray Milton as a man dedicated to his beliefs and willing to enter into a battle to defend those values. Within the church, Milton stood in the minority with his conservative beliefs, and at all times his family was his greatest support. This was a lesson that Wilbur, Orville, and Katharine took to heart. In later years, when the Wrights faced controversy over their invention of the airplane, they turned to their family for support and assistance. [1]

For most of September and October 1892, Wilbur and Orville, age 25 and 21 respectively, had the house at 7 Hawthorne Street to themselves. Milton was traveling on church business and Katharine, who graduated from Central High School in June, was visiting her brother, Reuchlin, and his family in Kansas City. The brothers were "living fine," according to Wilbur, who reported to Katharine that he and Orville were alternating cooking responsibilities:

Orville cooks one week and I cook the next. Orville's week we have bread and butter and meat and gravy and coffee three times a day. My week I give him more variety. You see that by the end of his week there is a big lot of cold meat stored up, so the first half of my week we have bread and butter and 'hash' and coffee, and the last half we have bread and butter and eggs and sweet potatoes and coffee.

Wilbur further elaborated that the housekeeper, Mrs. Miller, was astonished at times to find them keeping the house in good condition. In addition, there had not been any accidents, so Wilbur could not "embellish this letter with any thrilling descriptions of falling dishes or exploded gasoline stoves." [2]

The Wright children were often the only ones in the family home, for Milton was frequently away from Dayton on church business. After the restructuring of the Radicals into the Church of the United Brethren in Christ (Old Constitution) in 1889, Milton focused much of his energy on rebuilding the church. During the split, the Old Constitution attracted approximately 15,000 to 20,000 members, or about ten percent, of the total church population. The church needed to be reorganized from the ground up to provide an effective ministry for these members.

While new congregations and districts formed, the issue of property rights remained in the forefront of the minds of the Old Constitution leaders. Prior to the division of the church, many of those on the Liberal side of the argument attained high positions within the church. These positions assisted the Liberals, or New Constitution branch, in maintaining control of the various departments and funds of the church. Yet, the question remained, with the split of the church, did the Old Constitution or the New Constitution have ownership of the United Church of Brethren in Christ property? The Old Constitution argued that they supported the original Constitution and Confession of Faith therefore making them the true church. The New Constitution, on the other hand, contended that since they amended the Constitution by operating within the established procedures and the majority of the members favored the changes, they had a right to control all the property. [3]

The most valuable church asset was the United Brethren Publishing House in Dayton. Both sides wanted to retain control of the facility, and the lawsuit filed to resolve the dispute was the first of many throughout the country over the next five years. Milton, who served as the publishing agent for the Old Constitution from 1889 to 1893, led the fight to gain control of the publishing house. He set the dispute in motion on July 26, 1889, when he and two colleagues presented William J. Shuey, the New Constitution publishing agent, with a written demand to turn the facility over to them. Shuey refused. In response, Milton rented a building in the city of Dayton to serve as temporary quarters for his United Brethren Printing establishment. Within a few years, the facility moved from the first location to a building on South Broadway Street. Operations remained at this site until November 1897. [4]

While the Old Constitution established a publishing house, they did not immediately purchase any printing equipment. For the first four years of their operation, commercial printers completed all of the printing. This was the same time that the Wright brothers operated Wright & Wright, Job Printers, so Milton directed many of the printing jobs to his sons' business. [5]

The New Constitution board of trustees petitioned the Montgomery County Court of Common Pleas for a hearing to resolve the dispute over the ownership of the publishing house. After abundant legal maneuvering by both sides, the case came to trial on June 17, 1891. Since this was the first case heard in regards to the disposition of property, besides settling the dispute over ownership of the publishing house, the case would set a precedent for all the other cases involved in the disposition of the former Church of the United Brethren in Christ property. Both sides hired lawyers as well as prominent theologians to support their arguments.

After nine days of testimony, the panel of judges at the hearing unanimously ruled in favor of the New Constitution. The Old Constitution filed an appeal in the appellate court system, and the case was heard by the Supreme Court of Ohio on June 13, 1895. Once again, the court handed down a unanimous decision in favor of the plaintiffs, the New Constitution branch. [6]

Although the Old Constitution lost all lawsuits involving the disposition of the church property except for a case in Michigan, Milton achieved his goal within the church. By 1900, the Church of the United Brethren in Christ (Old Constitution) was the image of the same organization in which Milton was baptized many years before. None of the reforms advocated by the church's new constitution were incorporated into the Old Constitution branch of the Church of the United Brethren in Christ. [7]

As the Old Constitution restructured their church, Milton served many roles. At the 1893 General Conference, he was elected a bishop, and he was reelected at every subsequent conference until 1905. In 1893 he also assumed the additional duty of Supervisor of Litigations. In this role, with the assistance of Bishop H.T. Barnaby, Milton oversaw all the lawsuits over the disposal of the church property. In these roles, Milton spent much of his time traveling. He visited congregations, organized new conferences, and continued to carry forward the law suits.

While Milton was busy with church business in 1892, Wilbur and Orville modified the family home at 7 Hawthorne Street. On the exterior they built a wrap-around front and side porch, completing all the carpentry work themselves. When they reached the railing and balusters, the brothers divided the work. Wilbur turned the posts on a neighbor's lathe, and Orville installed them. Because they did not favor the ginger bread decoration on other West Side porches, the brothers constructed a simplified version. After they completed the porch, they continued the improvements by installing a fireplace in the parlor. [8]

7 HAWTHORNE STREET SHOWING THE PORCH BUILT BY WILBUR AND ORVILLE. (Courtesy of NCR Archives at Montgomery County Historical Society) |

The experience of living alone at 7 Hawthorne became a frequent occurrence over the next few years as Katharine enrolled in Oberlin College in 1894, and Milton continued to travel on church business. Both brothers adapted to the bachelor lifestyle. In fact, while both were of marrying age, neither showed any interest in the opposite sex or changing their single status. Wilbur, Orville, and Katharine seemed bound by an unspoken understanding to remain together and not marry. In later years, residents of Richmond, Indiana, recalled Wilbur courting a young lady in high school. There is no other example of Wilbur again paying attention to a young woman in a romantic way. In fact, friends suggested that eligible young women scared him. Of the two brothers, Orville was the closest to marriage. In the months following Katharine's high school graduation, Orville courted her childhood friend Agnes Osborn, but nothing ever resulted from the romance. [9]

Living as bachelors, Wilbur and Orville continued to follow the morals advocated by their parents. Neither drank alcohol or smoked although Orville tried tobacco once in his childhood. Following the Christian teachings of their parents, the Wright children also never worked on Sunday. Meant to be a day of rest, Sundays were spent together reading books or discussing ideas. [10]

While housekeeping and operating the print shop kept both brothers busy in the fall of 1892, they began to grow restless and began searching for a new challenge. Wilbur, never fully interested in the printing operations, had a lesser role in the business with the demise of The Evening Item and his editorial responsibilities. With Ed Sines overseeing the daily operations, Orville also had time to wonder about new business ventures for the two brothers.

During the spring of 1892, Orville purchased a new Columbia "safety" bicycle for $160. This was the second bicycle he had purchased, for in Richmond he borrowed three dollars from Wilbur to buy a used high wheel, or ordinary, bicycle. A few weeks after Orville purchased the safety bicycle, Wilbur, the more financially cautious of the two, bought a used Eagle for $80. [11]

Bicycles were first commercially introduced in the United States in 1878 when Colonel Albert Pope, a Boston merchant, began producing a high-wheel "ordinary." With their large front wheels and small back wheels, ordinaries were restricted in use to athletic young men with their limited control and high risk. Pope's bicycle, called Columbia, was modeled after a version constructed by the English company Bayliss, Thomas & Company. Pope's company concentrated on mass producing bicycles instead of the design details, and within two years, they were producing fifty a day. Within the next decade his company produced a quarter of a million bicycles. This increased production created a greater supply within the United States and contributed to the growing popularity of bicycles. [12]

In 1887, the safety bicycle, such as those purchased by the Wrights, appeared on the American market. Developed in England, the safety bicycle consisted of two wheels of the same size, a sturdy triangular frame, and a chain-driven system. The basic form of the safety was the same as today's modern two-wheeler, and its invention signified the beginning of the bicycle age. Easier to control than the ordinary, the safety bicycle opened the world of bicycles to a wide range of people. Its broad appeal also created greater opportunities for bicycle manufacturers and stores. [13]

The improvement and mass appeal of the bicycle coincided with the later stages of the Industrial Revolution in the United States. In the three decades following the Civil War, the transatlantic telegraph line, telephone, electric light, phonograph, and internal combustion engine were introduced. During the Industrial Revolution, some of the largest changes were in transportation. The railroad and steamship were dominant forms of transportation, and the safety bicycle was soon just as popular.

When it was first introduced, the safety bicycle sold for around $100. This was still a large amount for the average American in the 1890s but less than the higher priced ordinaries. The increased number of bicycles for sale and the lower price were two of the factors that helped cause the bicycle boom. As Jay Pridmore and Jim Hurd recount in their book on the history of the American bicycle, no technology had ever overtaken society with as much force or generated as great enthusiasm as the bicycle. Teenagers had a means to leave their neighborhoods unescorted, and women could remove their confining corsets and enjoy pedaling a bicycle. By the middle of the 1890s, at least 1.5 million bicycles were sold annually. [14]

Wilbur and Orville were just two of the many Americans who acquired bicycles in the midst of the new craze. With their new bicycles, Wilbur and Orville would take leisurely rides along the back roads around Dayton, both becoming enthusiastic over this new activity. In the same letter to Katharine where he reported on the shared cooking schedule, Wilbur related a recent bicycle ride. Leaving at 4:15 in the afternoon, the brothers decided to ride to Miamisburg via the Cincinnati Pike. Passing the Montgomery County Fair Grounds, they stopped to ride around the track a couple of times, and then continued on their way south. Encountering a large hill, Wilbur reported:

[They] climbed, and then we 'clumb' and then climbed again. To rest ourselves we called it one name awhile and then the other...Finally we got to the top and thought that our troubles were over but they were only begun for after riding about half a mile the road began to 'wobble' up and down....

Upon reaching Centerville, the brothers saw for the first time the home of Asahel Wright, where their grandfather, Dan Wright, had lived for a short time upon arriving in Centerville. Continuing onto Miamisburg, this time downhill instead of up, they then turned south to visit the prehistoric Adena Miamisburg Mound.

DRAWING INCLUDED BY WILBUR IN HIS LETTER DESCRIBING HIS AND ORVILLE'S BICYCLE RIDE TO CENTERVILLE. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress) |

The return trip, as narrated by Wilbur, was just as eventful. Departing at twentythree minutes to seven meant that they rode home in the dark. "By the time we reached Carrollton and Alexanderville all we could see was two light streaks where the wheels of wagons had rolled, the ground smooth and dry." At one point they almost ran into a cart loaded eight to ten feet high with boxes. "This experience set Orville's imagination (always active you know) to work," commented Wilbur. At one point, Orville quickly stopped his bicycle to avert running into a wagon crossing a small bridge. "When he came to the place he found no hill, no bridge, and no wagon, only a little damp place in the road which showed up black in the night." Wilbur and Orville's bicycling adventure ended safely when they arrived home at 7:35, thirty to thirty-one miles later. [15]

The following evening they rode out Covington Pike for a distance of just over seventeen miles. Wilbur favored long rides in the country, such as the one described above. Orville, on the other hand, enjoyed racing. He participated in at least three Y.M.C.A. sponsored races on unknown dates and won medals. Two of the medals are gold, signifying first place, and one is silver, for second place. The length of these races ranged from one half mile to two miles. [16]

With their mechanical aptitude, Wilbur and Orville were naturals at repairing both their own bicycles and those owned by neighborhood residents. Soon, with the popularity of bicycles increasing, the brothers found their repair services were in demand and the idea for a new business was defined. Soon after their father's return to Dayton, Wilbur approached him about the idea of a bicycle shop. Wilbur believed they could operate a show room and repair shop in a rented storefront, and Ed Sines could continue to operate the printing business. Believing that his sons would earn a profit from such a venture, Milton approved. [17]

Business plans were almost halted when Wilbur developed appendicitis shortly after the brothers' decision to open a bicycle shop. On November 2, Milton left late in the afternoon to meet Katharine's train from Kansas City, and when the two of them returned home, they found Wilbur in great pain. Milton quickly called Dr. Spitler, the family physician who had cared for Susan. Ascertaining appendicitis, Dr. Spitler recommended rest, diet, and care to avoid cold. In 1892, appendicitis was still a new diagnosis, and while an appendectomy was the recommended treatment in acute cases, it was a very risky and dangerous operation. Dr. Spitler chose not to subject Wilbur to this risk. The treatment recommended by the doctor worked and Wilbur did not need surgery, although he was still recovering in January 1893. [18]

With Wilbur's health improving, the brothers began establishing their bicycle business. In December 1892, they rented a storefront at 1005 West Third Street and began stocking parts for an opening in the spring at the start of the bicycle season. For a while, Orville divided his time between setting up the bicycle shop and working at the printing office with Ed Sines. While the repair business would be the major focus of the operation, the brothers also planned to sell new bicycles. Throughout the years of their business, they sold eight different brands: Coventry, Cross, Duchess, Envoy, Fleetwing, Halladay-Temple, Smalley, and Warwick. [19] These were the best bicycles on the market and the Wright brothers always advertised the quality of their stock since other Dayton bicycle stores carried lesser priced and lower quality brands. [20]

When Wilbur and Orville opened their shop, there were nine other bicycle shops in Dayton. Of those nine, only one, Frederick T. Ward's at 1402 West Third Street, was located on the West Side and near the brother's store. Also listed as bicycle repairers, the Wright's were only one of four businesses who repaired bicycles, and the only one on the West Side. The large increase in the number of bicycle shops in Dayton from 1890 to 1893 reflected the growing nationwide bicycle craze. In 1890 there was one bicycle dealer in Dayton, the next year there were four dealers and one bicycle repairer, and in 1892 the number changed to three dealers and two bicycle repairers. [21]

The Wright's bicycle shop opened in the beginning of April 1893. At the October meeting of the Ten Dayton Boys, Wilbur reported that while "times have been very hard and prices very unsteady, I have escaped bankruptcy." In order to sell new high quality bicycles, the Wrights offered payment plans and accepted trade-ins. The Wright Cycle Company maintained three rules in regard to payment by installment:

1. Purchasers will be expected to pay the agreed amounts at the agreed times unless there are very good reasons for not doing so.

2. Purchasers must call to see us at the agreed times whether able to pay or not. For persistent violation of this rule we will call in the wheel at once.

3. Persons out of employment must report regularly every week; otherwise the bicycle must be left with us until payments begin again. [22]

As long as buyers met these conditions, they were able to purchase a bicycle on installment. This financial plan allowed more people to purchase bicycles and expanded the shop's business. [23]

Most of the trade-ins accepted by The Wright Cycle Company were a total loss; they were older, cheaper safety bicycles that could not be guaranteed. But the brothers were able to find uses for some of the trade-ins. One bicycle, a Viking, Orville gave to his friend Paul Laurence Dunbar. Wilbur and Orville also built a tandem bicycle using the large wheels from two old high-wheel models traded for newer safety bicycles. Once they learned how to operate the tandem, they were a sight riding along the streets of West Dayton. Only one other person, Tom Thorne, ever successfully rode the unit, and he finished his ride face down in a mud puddle. [24]

With this successful joint business, the Wright brothers expanded their partnership to include a joint bank account. They established their account at the neighborhood branch of Winters National Bank located on the southeast corner of West Third and Broadway Streets. Trusting each other, Wilbur and Orville were free to draw from the account as needed. [25]

ORVILLE AND A GROUP AROUND A TABLE LOOKING AT PHOTOGRAPHS DURING A PARTY AT 7 HAWTHORNE STREET. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress) |

Though occupied with their bicycle business, Wilbur and Orville also found time to socialize with their family and friends. While the Ten Dayton Boys did not meet as often as when the club was formed, the ten members still found time to meet twice a year. Every Fourth of July they gathered for a picnic and in the winter they met for a banquet. At the Fourth of July picnics, entire families and guests attended. Thomas Coles remembered attending one of these picnics as a guest and watching Wilbur set up swings for the children. After completing the project, Wilbur stood to one side of the crowd for most of the day. In describing the event, Coles felt that "the strongest impression one gets of Wilbur Wright is of a man who lives largely in a world of his own, not because of any feeling of self-sufficiency or superiority, but as a man who naturally lives far above the ordinary plane." [26]

Besides participating in the Ten Dayton Boys events, Wilbur enjoyed camping and long bicycle rides. His childhood friend and fellow Ten Dayton Boys member, Ed Ellis, remembered camping with Wilbur when Wilbur's home-made canoe, gun, and fishing tackle were as important to him as his fellow campers. [27]

Like Wilbur, Orville did not always actively participate at parties, but it was for different reasons. Orville was painfully shy and not always socially adept. Jess Gilbert, a high school friend, described Orville at a party one time as sitting just inside the parlor door away from the other guests and party games. Gilbert found Orville not disdainful, haughty, or offensive, but preferring to be a passive observer by himself. [28]

As the brothers' new business venture became a success, Wilbur and Orville began to spend more of their time at the bicycle shop. Ed Sines continued to operate the printing business, located in the Hoover Block, for the brothers, and when Ed needed assistance they hired their brother Lorin. By 1893, Lorin worked full-time for his brothers as a bookkeeper at the printing office. In September of 1894, Wilbur, in a letter to his father, mentioned that Lorin was doing a good job at the printing office. "He made about $30 on the Y.M.C.A. labor day programmes and has the Eric minutes and several other good jobs on hand." Lorin continued working for his brothers until he was hired as a bookkeeper at The John Rouzer Company sometime between 1895 and 1896. While he was no longer employed full time by Wilbur and Orville, Lorin continued to assist them when needed. [29]

During 1893, the Wrights moved the location of their cycle shop to 1034 West Third Street. [30] With this move came a new name for the business, the Wright Cycle Exchange. The new location provided more room for the successful business, and the brothers were able to set up operations during the fall and winter, the slow periods in the bicycle business. [31]

In the profitable spring and summer months of 1894, business continued much as it had the previous year. By September, the sale of new bicycles had slowed, yet Wilbur reported to his father:

[T]he repairing business is good and we are getting about $20 a month from the rent of three wheels. We get $8.00 a month for one, $6.50 for another and the third we rent by the hour or day. We have done so well renting them that we have held on to them instead of disposing of them at once, although we really need the money invested in them.

With the slower business months ahead, Wilbur also asked his father for a loan of $150. He believed that the brothers would be able to repay the debt by the time Milton returned to Dayton. In his answering letter, Milton agreed to loan his sons the money. [32]

In the same letter, Wilbur asked his father's opinion about enrolling in a college course. Earlier in life, Wilbur desired to attend Yale University and become a minister, but his injuries from the sports accident had deterred him. Now, Wilbur, in good health for more than a year, began to reconsider enrolling in college. He told his father,

I do not think I am specially fitted for success in any commercial pursuit even if I had the proper personal and business influences to assist me. I might make a living but I doubt whether I would ever do much more than this. Intellectual effort is a pleasure to me and I think I would [be] better fitted for reasonable success in some of the professions than in business.

In order to attend college, Wilbur needed financial assistance from Milton. He could not meet all the expenses, an estimated $600 to $800, with his income from the bicycle business. Milton agreed with his son that he was not suited for life as a businessman and offered to assist with a college course. [33]

THE WRIGHT CYCLE COMPANY BUILDING AT 22 SOUTH WILLIAMS STREET. (Courtesy of Wright State University, Special Collections and Archives) |

Wilbur never enrolled in college, though, and this was the last time the matter was discussed. Instead, he focused on making the bicycle business a success. One of the first steps he took was to decrease the overhead costs in the bicycle shop. In October, in a letter to his father, Wilbur discussed moving the bicycle repair shop from 1034 West Third Street to the printing office at the Hoover Block. Business was slow and did not justify paying the rent for the storefront shop. [34]

While Orville spent most of his time at the bicycle shop, he did not completely separate himself from the printing business. In October, he assisted with typesetting for the Christian Conservator, the newspaper of the Radical faction of the United Brethren Church, while two employees were on strike. The Christian Conservator office was also located in the Hoover Block, and the Wrights were friends with many of the employees. [35]

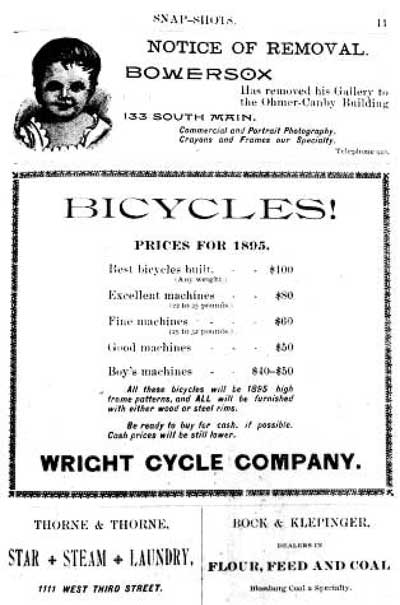

In the fall of 1894, the Wrights linked their printing and bicycle businesses with the introduction of a weekly magazine, Snap-Shots at Current Events. The first issue was released on October 20 and consisted of sixteen pages with a subscription rate of five cents to January 1, 1895, and twenty-five cents through July 1. While the magazine contained a variety of articles, the Wrights' interest in bicycles is reflected in the many references to the popular machine. Throughout the issues, advertisements appeared for the Wrights' bicycle shop as well as other West Side businesses. [36]

In the spring of 1895, the Wrights moved their shop once again. The new location at 22 South Williams Street provided more space and two floors. With the additional space upstairs, the brothers moved the printing business from the Hoover Block into the second level. The bicycle business, now named The Wright Cycle Company, occupied the first floor. The building at 22 South Williams Street was built in 1886 by Abraham and Joseph Nicholas. Prior to the Wrights' occupation, the building served as a grocery store, feed store, saloon, and boarding house. In 1895, J.H. Hohler owned the property, and as landlord he charged Wilbur and Orville $16 a month for rent. [37]

At approximately the same time the cycle shop moved to 22 South Williams, the Wrights opened a showroom in downtown Dayton. Located at 23 West Second Street, the new store was within two blocks of three other bicycle stores. It appears as though Wilbur operated the downtown store, for on May 24, 1895, Milton noted that he visited Wilbur's bicycle store on West Second Street. Faced with stiff competition and few additional customers, Wilbur and Orville closed the downtown store in the fall and focused all of their efforts on the main shop in the West Side. [38]

Not just businessmen, the Wright brothers were known locally as bicyclists. In fact, one of Orville's accidents received coverage in the West Side section of the Dayton Daily Times. As reported on November 15, 1895, "Orville Wright of Hawthorn street, while riding his bicycle on Third street, ran into Dr. Francis' big dog. His wheel was badly damaged, but Orve came down on top of the dog and neither were hurt." [39]

The brothers, avid bicyclists themselves, took part in local bicycle events both as participants and to promote their business. On January 1, 1896, the Y.M.C.A. sponsored a bicycle show at its annual New Year's reception. Between two and three thousand people visited the Y.M.C.A. on New Year's Day to view exhibits and enjoy lemonade and cake. The bicycle exhibit was the "greatest point of interest and the most novel feature of the reception." Overflowing the designated lecture hall, the bicycle exhibits were also set up in another room. Nine cycle firms exhibited their products, including The Wright Cycle Company. While there is no detail on the Wrights' display, the Dayton Journal reported:

The display was a most beautiful one and the first of the kind ever attempted in the city. The Crescent people had a gold and black crescent set with incandescent light. The Davis Sewing Machine Company...had their exhibit under the shelter of a great Japanese parasol, from which hung pendant a large number of incandescent lights, beautifully shaded with colored silks.

While The Wright Cycle Company exhibit might not have been elaborate, the brothers worked hard to set up a display for the show. Milton, in his diary, noted that Wilbur and Orville were busy preparing for the show on both December 31 and New Year's Day. [40]

In the February 1896 issue, Snap-Shots at Current Events underwent a change. Instead of merely mentioning bicycles throughout the magazine as in the past, the new issues were devoted to them. Published by The Wright Cycle Company under the shortened name Snap-Shots, the magazine was "sent free by mail to any one who will pay postage on it, or may be had for the asking at a number of places, list of which will be given later." Publication of the magazine continued until April 17, 1896. [41]

Each year the profits from the bicycle business were more than double the previous year, and Wilbur and Orville began developing new plans to expand their business in the fall of 1895 by designing their own brand of bicycles. Orville reported the brothers' rationale to their father in October 1895:

Our bicycle business is beginning to be a little slack, though we sell a wheel now and then. Repairing is pretty good. We expect to build our wheels for next year. I think it will pay us, and give us employment during the winter.

Each of the bicycles constructed by the Wrights would be a high quality machine constructed to order. [42]

ADVERTISEMENT FOR BICYCLES FROM THE WRIGHT CYCLE COMPANY IN FEBRUARY 29, 1896, SNAP-SHOTS. (Courtesy of Dayton and Montgomery County Public Library) |

In order to produce bicycles, the Wrights needed to update the bicycle shop equipment for manufacturing instead of repairs. In a catalog issued in 1896, the Wrights noted that they were refitting their salesroom as well as adding new machinery. The new equipment included a turret lathe, drill press, and tube-cutting equipment which was installed in the back room and on the second floor of 22 South Williams. To operate the machinery, the brothers installed a line shaft on the ceiling. In need of an engine to power the line shaft, the brothers designed and built their own single-cylinder internal combustion engine powered by the city natural gas line that ran into the shop. [43]

Initially the Wrights used pre-made bicycle frames and other materials for their bicycles. When the Wright bicycles were completed and ready for sale by May 16, 1896, they joined what would become in 1897 approximately 3,000 American businesses who were manufacturing bicycles, parts, or sundries. The Wrights' line of bicycles included a "Wright Special" and a ladies model. At the beginning of the 1896 cycling season, in addition to the Wright Special, the Wrights issued a Van Cleve model that was named after their Wright ancestors and in honor of the Dayton centennial. The Wright Special was cheaper than the higher priced Van Cleve. The Van Cleve, the Wrights announced in a bicycle catalog, "will be a wheel of the highest grade, and will embrace several novel features of our own invention. We are confident it will be a credit to our city and ourselves." The first Van Cleve bicycles sold for sixty to sixty-five dollars. By 1900, with the decreasing demand in bicycles, the price dropped to between thirty-two and forty-seven dollars depending upon the features incorporated into each specific bicycle. [44]

One of the "novel features" of the Van Cleve was its wheel hub. Designed by the brothers, the wheel hubs were dust proof and retained oil to the extent that they only needed to be oiled once every two years. This was achieved by containing the oil inside the hub instead of outside where dust would stick to it and dirty the mechanism. In addition, the Wright brothers designed their own coaster brake. [45]

Later in the 1896 season, the Wrights unveiled the St. Clair bicycle named after Arthur St. Clair, the first governor of the Northwest Territory and one of Dayton's founders. The St. Clair was a lower priced line that sold for $42.50 when it premiered. By 1899, when production ceased, the priced had fallen to $30. In 1900, with some St. Clair bicycles still in stock, The Wright Cycle Company promised to sell the few remaining models "very cheap." [46]

Sometime during production of the Wright bicycles, Wilbur and Orville began to manufacture the entire bicycle. A 1900 catalog for the Van Cleve detailed the assembly process used at the 22 South Williams Street shop. The wooden or metal-rimmed wheels, as well as the cranks and hubs, were built in the cycle shop. In addition, the frames were made in the shop using raw tubing of seamless quality. Each frame was then brush coated with five coats of enamel to produce a durable finish. The enamel was most likely applied in a shed located at the rear of 22 South Williams. [47] When the bicycle business relocated to another building, Wilbur and Orville applied the enameling using a sheet iron furnace. [48]

With the addition of bicycle manufacturing, The Wright Cycle Company provided Wilbur and Orville with a good income and in many people's eyes, satisfying careers. Yet once again, the brothers began looking for other ventures. Through the years, Orville continued to tinker with various inventions. At one point, he invented an adding machine that would also multiply, and he also experimented with simplifying the typewriter. In 1896, Orville became fascinated with an automobile that the Wrights' friend and part-time employee, Cordy Ruse, had built. The Wrights would sit and talk for hours with Cordy about his new horseless buggy; yet Wilbur was not impressed. One day he suggested to Cordy that he fasten a bed sheet under the automobile to catch all the parts that dropped off. While Orville tried to persuade Wilbur to pursue the automobile business, Wilbur refused. Feeling that the horseless carriage would never be practical, Wilbur was for once wrong. [49]

ORVILLE WRIGHT (RIGHT) AT WORK IN THE WRIGHT CYCLE COMPANY, 1897. (Courtesy of Wright State University, Special Collections and Archives) |

In the fall of 1897, the Wright brothers moved The Wright Cycle Company and their printing shop to new quarters at 1127 West Third Street. Charles Webbert, a local plumber whose shop was at 1121 West Third Street, owned the double building at 1125 and 1127 West Third Street that was formerly a dwelling and recently remodeled. The Wrights rented the western half of the building and Fetters & Shank, undertakers, leased the eastern portion. The Wrights' paid $16.66 a month for rent, a slight increase from the $16.00 per month for 22 South Williams Street. As at 22 South Williams Street, The Wright Cycle Company occupied the first floor store front and the printing business was located on the second floor. [50]

Shortly after moving to their new shop, in March 1898, the rivers around Dayton flooded once again, and West Third Street was submerged under water. Frank Hamburger, who operated a hardware store on Third Street near the Wrights' bicycle shop, faced losing his stock of nails. Stored in the cellar of his store, once wet, the nails would rust and be useless. Hearing of the hardware store owner's quandary, Wilbur and Orville went to the store to offer assistance. They removed their suit coats and assisted Frank in removing all the nail kegs from the cellar. The brothers would not accept any compensation for their assistance, but, for many years, as they needed various hardware items, Frank gave the items to them at no cost. [51]

For the last several years, Ed Sines oversaw the Wrights' printing business while the brothers were busy with the bicycle shop. Ed injured his knee in 1898, and he was forced to quit working in the shop. Instead of searching for an individual to continue operating the business, Wilbur and Orville sold all the equipment. Stevens & Stevens, run by Tom and Bob Stevens who had worked as boys for the Wrights on the West Side News, purchased the entire printing office equipment. [52]

With the upstairs of 1127 West Third Street now vacated of printing machinery, the Wrights used the space to manufacture their bicycles in the off season. While business was slow through the winter, customers occasionally stopped by the shop seeking repairs or to use the hand operated air pump kept inside the front door. Finding it tiresome to interrupt their work to let people in to use the pump, Wilbur and Orville rigged up a bell system that let them know if the caller was a customer or was only using the pump. They used a two-tone bicycle bell for the system. One tone would ring when the front door opened, and the second would sound when the door closed. The air pump was also rigged to the bell, so the brothers would know if the person downstairs opened the door, took the air pump off the wall, and then left. Wilbur and Orville would then know it was not necessary to leave their work upstairs to assist a customer. Only when the ringing bell signaled the opening of the front door and was not followed by the bell signaling the removal of the pump would one of the brothers go downstairs to greet the customer. [53]

Both Wilbur and Orville were content with their bicycle business. Unlike the print shop which was of more interest to Orville, both brothers enjoyed the operations and repair work that were part of the bicycle shop. The business provided a sufficient income as well as an outlet for their interest in machinery and hands-on work. Through the construction of their own brand of bicycles and the repair work, Wilbur and Orville further developed their mechanical skills that their parents had encouraged since childhood.

During the years that the Wright brothers established their bicycle business, their father was in the midst of the split between the Liberals and Radicals within the United Brethren Church. His experiences in this controversy further illustrated to Wilbur and Orville, as well as their sister Katharine, that family was of the utmost importance. In later years it would become apparent that the Wright brothers took these experiences to heart. The greatest supporters of them throughout their lives were their siblings and their father.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

daav/honious/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 18-Feb-2004