|

Dayton Aviation

What Dreams We Have The Wright Brothers and Their Hometown of Dayton, Ohio |

|

Chapter 7

Improving The Airplane

The four successful flights of December 17, 1903, while a gigantic achievement, were in some respects just a step in moving the Wright brothers forward on the path of progress toward mastering the airplane and perfecting human flight. While the first free, controlled, and sustained flights in a power-driven, heavier-than-air machine occurred on that day, Wilbur and Orville's invention was not practical. The 1903 airplane's performance could not be predicted and relied upon. For the next two years, the Wright brothers focused on improving their invention and making it a practical machine.

Orville's telegram announcing the successful first flight reached the Wright home at 5:25 in the evening of December 17, 1903. It read,

Success four flights Thursday morning all against twentyone mile wind started from level with engine power alone average speed through air thirty-one miles longest 57 seconds inform press home Christmas. Orevelle Wright

When Katharine arrived home from Steele High School, her father excitedly shared the news of her brothers' success. In the transmission, two errors appeared in the message: Orville was spelled Orevelle, and the longest flight was reported as 57 seconds instead of 59. Despite the small errors, the message was clear. Wilbur and Orville were successful, and, the best news of all, they would be home by Christmas. [1]

Carrie agreed to hold dinner while Katharine walked to Lorin's house at 1243 West Second Street to share the news. On her way, Katharine stopped to send a telegram to Octave Chanute informing him of her brothers' success. After hearing the great news, Lorin agreed to provide the information to a Dayton newspaper as Orville requested in the telegram. After dinner, Lorin went to the Dayton Journal office and spoke with Frank Tunison, the Associated Press representative. Tunison, after Lorin relayed the news of the first successful power-driven, human-controlled flight, was not interested in the story. He responded that if they had flown fifty-seven minutes instead of seconds then it might be newsworthy. [2]

While news of the first flight did not capture Tunison's attention, a young reporter, Harry P. Moore, from the Norfolk Virginian Pilot, found the story of interest. The telegraph operator in Kitty Hawk asked if he could share the story with his friend Moore, but the Wrights, wanting the story to originate from Dayton, requested that he not share the news of their flight with any reporters. Their request went unheeded, and the Virginian Pilot was the first newspaper to run a story regarding the first flight. However, with only the telegram contents as a source, Moore was forced to fill many of the story's gaps with his own imagination, and the resulting story was far from the truth. [3]

Moore's article described a three-mile flight at an altitude of sixty feet that traveled over the sand hills and ocean waves of the North Carolina coast. In order to propel the machine up into the air, a six bladed propeller was attached to the bottom of the machine, and a second propeller was used to push the flying machine through the air. The engine was located beneath the "navigator's car" which featured a fan-shaped canvas rudder. The rudder moved up and down and side to side for control. The author felt that Wilbur's exclamation of "Eureka!" at the conclusion of the flight summed up the magnitude of the brothers' success. [4]

After the Associated Press declined to put Moore's account about the first flight on the wire, the Virginian Pilot sent inquiries to twenty-one newspapers asking if they would be interested in running the article. Five newspapers ordered the story. The New York American and the Cincinnati Enquirer ran the entire story the next day. The Chicago Record-Herald and the Washington Post delayed running the story, but both eventually did use it. The Philadelphia Record was the only purchaser who never printed the story. [5]

It was not until December 18 that the Dayton papers recognized the success of their citizens. The Dayton Herald ran a summary of Moore's article on the front page on that day and an additional article on December 19. The Dayton Daily News ran an article on December 18 that accurately detailed the flights, and on December 19, the paper ran a brief article announcing that Wilbur and Orville, after several successful flights, were on their way home from Kitty Hawk to spend Christmas with their family. The Dayton Journal also carried an accurate account of the flight. As did the Dayton Daily News article, the story quoted the telegram received by Bishop Wright and described the plane in some detail. [6]

While the newspapers ran stories of the first flights, the brothers quietly prepared to return home. Wilbur and Orville disassembled the flying machine to be crated and sent back to Dayton and then departed Kitty Hawk on December 21. They arrived in Dayton at 8:00 p.m. two days later. For their first home cooked meal in many weeks, Carrie prepared porterhouse steaks and a fancy dessert. Prepared for large appetites, Carrie assured them that there was more of everything. The one thing she did not expect was Orville's unquenchable thirst for milk. As Orville consumed glass after glass, Carrie began watering down what little milk was left, certain that he would not notice. She was wrong; he noticed and complained that she was cheating him by "dairying" the milk. For the rest of their lives, the story of the "dairied" milk was a joke between Carrie and Orville. [7]

When the Wright brothers saw their mechanic, Charlie Taylor, they did not celebrate the success of the airplane they had all constructed. Always focused on their project, the brothers and Charlie discussed needed improvements and the necessity of building a new engine since the first one was damaged after the last flight on December 17. In fact, the brothers' first words to Charlie were not about the successful flights but a new engine. Next, Wilbur and Orville discussed making improvements in the control. Charlie found that the brothers, "were always thinking of the next thing to do; they didn't waste much time worrying about the past" or in this case celebrating. [8]

Concerned and surprised over the incorrect stories that were flourishing about their success, one of the first things Wilbur and Orville completed upon returning to Dayton was a press release for the Associated Press. The release consisted of a statement on their flights that the brothers requested be published. Many of the Associated Press newspapers printed the information on January 6, 1904. In sending a copy of the press release to Chanute, Wilbur informed him, "Nothing more will be given out, as we prefer to keep the story to ourselves till we are ready to make a full statement later in the year." [9]

Nine days after the December 17 flight, Augustus Herring, who visited Kitty Hawk in 1902 with Octave Chanute, wrote to Wilbur and Orville suggesting that the three of them form a partnership. Herring claimed that he had also reached a solution to the problem of powered flight, and he further asserted he was the originator of the Chanute-Herring two surface glider of 1896. As the inventor, he had already been offered a "substantial sum" for his rights in any future patent interference suit with the Wrights. Feeling that Herring's claims were false, Wilbur wrote Chanute, "But that he would have the effrontery to write us such a letter, after his other schemes of rascality had failed, was really a little more than we expected. We shall make no response at all." [10]

The Wright brothers were correct in ignoring Herring's offer of a partnership, for his threat was empty. Chanute and Herring had attempted and failed to obtain a patent on their 1896 glider, and study showed the only similarity between the Chanute-Herring glider and the Wrights' plane was that they both used a modified Pratt truss to turn the multiple wings into a beam structure. While he had no valid claim to any of the technology used by the Wrights, Herring's letter did reinforce the need for Wilbur and Orville to continue to pursue their patent application. [11]

Following the U.S. Patent Office examiner's advice for the brothers to work with a patent attorney, Wilbur began searching for a qualified lawyer. Two friends, John Kirby and Will Ohmer, recommended that Wilbur contact Henry A. Toulmin, an attorney in nearby Springfield. Wilbur and Orville immediately liked Toulmin and his services. Toulmin was confident that he could use the original application as a starting point for a broad, airtight patent that would protect the brothers' invention. But he warned Wilbur and Orville that the process would be lengthy, and he recommended that they keep quiet about the details of their aircraft. He also encouraged that they apply for a patent based on the 1902 glider instead of a powered airplane in order to avoid having to demonstrate the success of their machine. [12]

By January 1, 1904, Wilbur and Orville were back at work on a new flying machine and engine. While the flights of December 17 were successful, in no way was their invention practical, and the brothers still saw ways to improve their flying machine and immediately set to work to accomplish them. Since most of their time was spent on aeronautics, Charlie Taylor oversaw the day-to-day operation of the bicycle business as well as assisting the brothers when needed on the airplane and engine. At this time, a number of Wright bicycles in the shop were in various stages of assembly. These were completed and sold, but the construction of no new bicycles was undertaken after Wilbur and Orville returned from Kitty Hawk. [13]

One of the brothers' first priorities was the immediate need for a new engine since the 1903 engine was destroyed in the December 17 accident. While Wilbur worked with Toulmin on the patent, Orville and Charlie started constructing three new engines: one was for experiments [14]; one for the 1904 plane, the Wright Flyer II; and the other was a V-8 that was never completed. The brothers had given Charlie Taylor a micrometer for Christmas, and he put it to immediate use constructing the new engines. For his part, Orville visited Harry Maltby, the Vice President and Superintendent of The Concord Manufacturing Company, to see about patterns and getting castings for cylinders and pistons for the new engines. Following this meeting, Maltby decided he could not complete the work. [15]

Chanute visited Wilbur and Orville in Dayton on the afternoon of January 22 to discuss the brothers' airplane. While he was in town, Chanute discussed the merits of entering the St. Louis Exposition, a celebration honoring the centennial of the Louisiana Purchase that included an aeronautical exhibition. Based on their success in Kitty Hawk, Chanute felt that the Wrights should exhibit their invention immediately, for there was a fortune to be made in prize money from competitions and demonstrations. Wilbur and Orville considered entering the St. Louis competition; they even went so far as to travel to St. Louis to inspect the flying field. Yet, the brothers never seriously considered entering the competition. The requirements to win the grand prize money were far and above the best results of their 1903 flights, and there was no prize money available for consolation showings. The most compelling argument of all was that their airplane would not be protected by a patent. It would be foolish to stage a demonstration that would make their experiment available for inspection by competitors without the patent to protect their invention. [16]

Wilbur and Orville began to focus their attention on the construction of a new plane and the upcoming experimenting season. In a change from the last four years, instead of traveling to Kitty Hawk, they elected to remain in Dayton. For the site of their experiments, the brothers chose Huffman Prairie. The prairie was located eight miles northeast of Dayton along the Dayton, Springfield & Urbana (DS&U) Interurban Railway at the intersection of Dayton-Springfield Pike and Byron and Yellow Springs Road. The nearest DS&U station, Simms, was adjacent to the prairie. Torrence Huffman, President of the Fourth National Bank, owned the onehundred acre prairie used as a cow pasture and the surrounding area that was farmed by tenants. He agreed to let Wilbur and Orville use the site free of charge for their experiments as long as they drove any horses and cows in the pasture outside the fence prior to any flying. [17]

Covered with waist-high weeds and large hummocks the field did not immediately appear suitable for flying. Wilbur described the site to Chanute several months after the Wrights began their experiments:

We are in a large meadow of about 100 acres. It is skirted on the west and north by trees. This not only shuts off the wind somewhat but also probably gives a slight downtrend. However, this matter we do not consider anything serious. The great troubles are the facts that in addition to cattle there have been a dozen or more horses in the pasture and as it is surrounded by barbwire fencing we have been at much trouble to get them safely away before making trials. Also the ground is an old swamp and is filled with grassy hummocks some six inches high so that it resembles a prairie-dog town. [18]

WILLIAM WERTHNER (Courtesy of Dayton and Montgomery County Public Library) |

The flying field described by Wilbur was historically farmland. The Mercer family, the first Euro-Americans to settle in what is now Bath Township, established a farm near the future location of Fairfield. The number of farms in the township steadily increased, although the land surrounding the prairie was less populated due to potential flooding from the Mad River. [19]

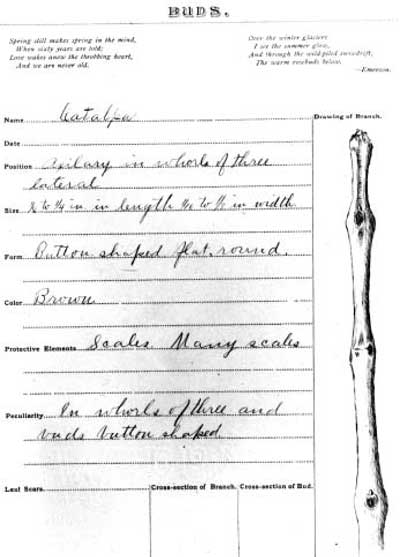

The Wright brothers were familiar with the acreage, for William Werthner, a science teacher at Central High School, led two generations of students to the prairie for field work. Orville and Katharine had both experienced Werthner's introduction to prairie flora and fauna. As a student, Orville filled a notebook full of observations and sketches of wildflowers from the prairie. While this experience did not cause the brothers to pick Huffman Prairie as their testing ground, it did create a familiarity with the site. The site possessed four advantages for the Wrights: it was located next to the interurban line; it was fairly isolated; there was no fee; and the field was available for immediate use. [20]

In April Wilbur and Orville began construction of a wooden hangar at Huffman Prairie. It was located on the southeastern edge of the field as far from Simms Station as possible. Similar to the 1903 hangar at Kitty Hawk, the new hangar had braced walls and a large door at each end that could be opened like an awning. The entire structure measured approximately twenty-five by forty feet. The construction was slow due to bad weather, but the hangar was completed on April 15. [21]

CATALPA BUD INFORMATION FROM ORVILLE WRIGHT'S HIGH SCHOOL BOTANY BOOK. (Courtesy Wright State University, Special Collections and Archives) |

By the middle of April, Wilbur and Orville spent much of their time in the hangar assembling the Wright Flyer II. The first mention of the brothers' use of Huffman Prairie Flying Field was by their father in his diary. On April 20 he recorded, "Wilbur went out to Simms to work on his flyer." The new airplane was similar to the 1903 plane except for the wing camber and spars. The camber was altered from 1/20 to 1/25. The spars, instead of being constructed of spruce, were of white pine. These two changes were in error, and by 1905 Wilbur and Orville had returned to the 1903 specifications. [22]

In January 1904, the brothers had informed Chanute that they were planning to build three machines which they would exhibit several places. After they decided not to exhibit and publicly demonstrate their invention but to focus on making the airplane more practical, the brothers altered their construction plans. By April they concentrated on building one plane, the Wright Flyer II. [23]

On May 15, Wilbur informed Chanute that this plane was nearing completion. He and Orville planned to finish in a day or two. Prior to flying the plane, the brothers planned to conduct some machinery tests. The tests produced excellent results showing that the engine was producing an increased rate of power over the 1903 engine. As soon as the brothers were ready to conduct their first experiment with the 1904 flying machine, rain began to fall. By May 20, rain had been falling for six or seven days, and the flying field was covered with standing water. [24]

Optimistic that the weather would improve, Wilbur and Orville invited representatives from the Dayton and Cincinnati papers as well as the Associated Press to observe a flight on May 23. Just when the brothers were ready for a flight, the wind died. With too little track on which to build speed, the trial was a failure. In 1926 Orville remembered during the flight attempt on May 23, "the machine ran down the track and slid off into the grass without getting into the air. The motor had begun skipping immediately the machine was set in motion." A number of the observers returned two days later, but no test was made due to heavy rains. The following day the rain did not decrease, and an even smaller number traveled to the Huffman Prairie Flying Field in hopes of seeing a flight. The rain finally let up in the afternoon, and by the time the second trial was made on May 26 only two or three witnesses were at the flying field. [25]

Among the few onlookers were members of the Wright family. Milton, along with Lorin and his family, took the interurban line out to Simms Station together on May 23 in the hopes of seeing Wilbur and Orville fly. The group returned two days later "to see an aeronautical flight, but a rain came up & hindered." Milton was back at the Huffman Prairie Flying Field on May 26 to see the first flight of the year. His diary entry recorded his first observations of his sons' invention, "Went at 9:00 car to Huffman farm at 2:00 Orville flew about 25 ft. I came home on 3:30 car. It rained soon after." [26]

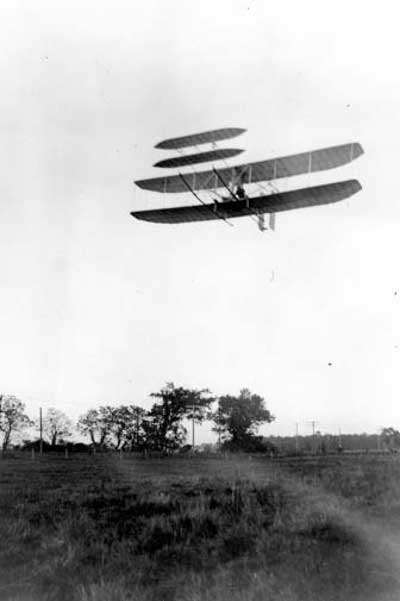

1904 WRIGHT FLYER II IN FLIGHT AT HUFFMAN PRAIRIE FLYING FIELD, AUGUST 5, 1904. (Courtesy of Wright State University, Special Collections and Archives) |

In the following six months, Wilbur and Orville made 105 flights with a total flying time of forty-nine minutes. Charlie Taylor spent the majority of his time with the brothers at the flying field. He assisted in the construction of the hangar and catapult as well as, in his words, served, "as sort of airport manager." Another one of his tasks was to serve as one of the timekeepers of each flight. According to Charlie, all flights were timed with at least three stop watches. One watch was held by either Wilbur or Orville, one by Charlie, and one was carried on the airplane. With all the time that Charlie and the Wright brothers spent at Huffman Prairie Flying Field that year, the bicycle business suffered. There was little time to keep the business operating, and by the next year, the brothers closed the shop. [27]

After the fiasco of the exhibition flights for the newspaper reporters, the Wrights preferred not to publicize their experiments. In fact, they timed each flight to coordinate with the interurban schedule to avoid unwanted observers. As Wilbur shared, "by selecting times when no cars were in sight we had been able to make flights of ten to fifteen minutes in almost perfect secrecy, except for the neighbors, who were witnesses to all our flights." [28]

Dave C. Beard and his family lived nearest to the Huffman Prairie Flying Field and were some of the neighbors to which Wilbur referred. Beard leased the property from Torrence Huffman, and one day Huffman mentioned to Beard that the Wrights would be using the property for flying experiments. Remembering that Huffman shared his belief that he thought the brothers were foolish, Beard emphasized that he always had faith in Wilbur and Orville. Mrs. Beard kept a close watch on the Huffman Prairie Flying Field when the brothers flew. If she saw the airplane rise in the air and then immediately drop from sight, she sent one of her children to the flying field with a bottle of liniment. [29]

Other neighbors at the Huffman Prairie Flying Field included the Harshmans, the Millers, and Amos Stauffer. All of them occasionally visited the flying field to watch the Wrights' spectacular invention and talk with the brothers. Beard found both Wilbur and Orville to be no different from common folks, and he perceived them to be very friendly with gentlemen's manners. As the flights increased in length, their experiments also attracted the attention of two supervisors on the DS&U line, Mr. Brown and Mr. Reed. [30]

With the low and unpredictable winds that occurred at the Huffman Prairie Flying Field, the brothers developed a starting apparatus in August 1904. They found that using a track system as they had at Kitty Hawk required them to lay up to 240 feet of track to get up flying speed needed for the low winds at the flying field. Only a few areas of the field were free of enough hummocks to allow for a track that long, and on more than one occasion, after Wilbur and Orville spent time laying the track, the wind direction changed and the track had to be relocated. With the addition of a starting device, the brothers felt they would be able to fly in calm winds and practice circling. The starting apparatus they devised consisted of a derrick with a 1,600-pound falling weight. By dropping the weight which was attached to ropes and pulleys, a 350-pound pull was produced that put the machine into the air after a run of fifty feet. The catapult system, or derrick as Wilbur referred to it in his diary, was tried for the first time on September 7. By September 18, Wilbur and Orville had made eleven starts with the new system, and they found, "it seems to operate perfectly and exactly according to calculations so far as we can measure." [31]

With the catapult system successfully functioning, the Wrights began attempting to fly in a circle. Their first trials were on September 15, and though they were not successful, during each of the two trials the plane covered a distance of one-half a mile; Wilbur also successfully flew a half circle. The brothers renewed their efforts on September 20. Wilbur completed the first circle in an airplane during this second trial. In describing the flight to Chanute, Wilbur concluded, "Since we have been making longer flights and getting more practice, the machine is becoming much more controllable and now seems very much like our gliders at Kitty Hawk." [32]

The flights of September 20 were observed by Amos I. Root, the editor and publisher of Gleanings in Bee Culture. Driving over 175 miles from Medina, Ohio, to verify rumors he had heard of airplane flights occurring in a cow pasture outside of Dayton, Amos boarded with the Beard family whose farm house was the closest to the Huffman Prairie Flying Field. Not greatly impressed with the airplane flights they viewed from the house, the Beard family was more awed by Root's long and successful auto journey from Medina. On the morning of September 20, Root walked over to the flying field and introduced himself to the Wright brothers. The Wrights immediately liked Root and allowed him to watch the trials. Root's observations of the first complete circle flown by an airplane were contained in an article in his magazine that accurately described the Wright brothers flying machine and experiments for the first time. Interested in the experiments, Root continued to update his readers on the Wright brothers' experiments throughout the next two years. He even offered the editor of Scientific American the opportunity to reprint his original article, but the editor declined. Root's articles in Gleanings in Bee Culture were the only accurate coverage of the brothers' work. [33]

Despite their welcome to Root, Wilbur and Orville were becoming wary of publicity. In a letter to Chanute, Wilbur described the situation,

Up to the present we have been very fortunate in our relations with newspaper reporters, but intelligence of what we are doing is gradually spreading through the neighborhood and we are fearful that we will soon have to discontinue experiment. If your business will permit you to visit us this year it would be well to come within the next three weeks. As we have decided to keep our experiments strictly secret for the present, we are becoming uneasy about continuing them much longer at our present location. [34]

Chanute responded to Wilbur's suggestion by traveling to Dayton to view their flying machine as soon as he was able. He witnessed his first flight of the Wright brothers' airplane on October 15. Unfortunately, after the third trial a minor accident occurred which prohibited any further flights, and the remainder of the day and the following week were spent repairing the machine. [35]

The Wrights discontinued the 1904 experiments on December 9. The flights were highlighted by the success in turning a complete circle in the air. After the first complete circle on September 20, the brothers continued their experiments, and on November 9, they flew four circles of the field in a flight lasting just over five minutes. Despite their advancements, Wilbur and Orville were still having problems with the pitch and the elevator, but the resolution of these problems would have to wait until the 1905 season. [36]

Their United States patent application, as well as various foreign patent applications, were never far from the brothers' thoughts as they conducted the 1904 experiments. In November, the U.S. Patent Office once again rejected their application. Despite the negative results, Wilbur remained optimistic when he wrote Chanute that "The American office has again rejected our claims but in doing so has suggested that the objections might be removed by slight changes in the wording of the claims which in nowise affect them for our purposes; so it seems probable that we will get all that we have claimed." [37]

While they struggled through the patent application process, Wilbur and Orville also wondered what to do with their invention. In October, Wilbur ended a letter to Chanute with the statement, "In fact, it is a question whether we are not ready to begin considering what we will do with our baby now that we have it." From the beginning of their pursuit for a solution for human flight, the brothers were attracted to the research for the challenge it represented, not the potential profit. Not expecting to receive back any of the money they spent on their research, Wilbur and Orville did not allow the experiments to interfere with their business. After their initial success, the brothers chose to devote their full attention to perfecting the problem of controlled and powered human flight. After this decision, the brothers shared with Albert Zahm, "as our financial future was at stake we were compelled to regard it as a strict business proposition until such time as we had recouped ourselves." [38]

The Wrights' first potential customer was Brevet Lieutenant Colonel John Edward Capper, Royal Engineers of the British military. Capper arrived in Dayton on October 24, 1904, to meet with Wilbur and Orville, and the events of the day set the precedent for future meetings with potential clients. The brothers did not show Capper their airplane, but they shared photographs of their invention in flight, something they would not do for subsequent clients. To support their claims, they explained the basics of their technology. Capper found the presentation convincing, but since he was not authorized to negotiate for the British government, he encouraged the Wrights to send a proposal. The brothers informed him they weren't ready to conduct business. [39]

It wasn't until January 1905, with the successful flights of 1904 behind them, that the Wrights felt they were ready to sell their invention. Predicting the first use of the airplane would be in warfare, they believed their invention would deter wars through their scouting ability, not for their destructive potential. After military use, the brothers believed the airplane would be accepted in the following order: for use in exploration, then transportation of passengers and freight, and finally for sport. Based on their assumption that the first use of the airplane would be by the military, Wilbur and Orville decided to focus their sales efforts in that direction, but they would not have excluded offers from other purchasers. While England had expressed an interest through Capper, Wilbur and Orville felt they should offer the United States government the first opportunity to purchase the airplane. Uncertain how to approach representatives of the United States government, Wilbur met with Congressman Robert M. Nevin at his Dayton home on January 3. Nevin suggested that Wilbur and Orville describe the airplane's performance and their terms for the sale in a letter he would forward to Secretary of War William Howard Taft. [40]

The Wrights drafted a letter to Nevin on January 18. Stressing the successful flights of their flyer, the brothers offered their invention for sale to the United States. Unfortunately when the letter arrived at his office, Nevin was out sick. Unaware of the agreement between Nevin and the Wrights, an aide forwarded the letter to the U.S. Army Board of Ordnance and Fortification. Major General G.L. Gillispie, president of the Board, replied through Nevin's office. Gillispie's response revealed the fact that he did not give much credit to the Wrights' claims, and he informed them that the government did not provide financial assistance for the development of a flying machine. [41]

Having contacted the United States government regarding their airplane, the Wrights also re-established negotiations with Britain. Writing to Capper, Wilbur summarized the results of the 1904 experiments and offered the sale of their airplane. Based on Capper's enthusiastic recommendation, his immediate superior, Richard Ruck, wrote to the Wrights and invited them to submit a description of their machine and terms of sale. The Wrights offered to provide an airplane capable of carrying two men through the air at a speed of not less than thirty miles per hour. The price would be at a rate of £500 for each mile covered during the best of several trial flights. In addition, they could negotiate the sale of their impending patents so the English could construct their own machines. [42]

Ruck was only interested in purchasing a flying machine capable of flying at least fifty miles. Using the Wrights' formula, the cost of the machine would be no less than £25,000. This sum was far greater than Ruck was allocated to expend, and the Wrights' proposal moved to the Royal Engineer Committee, the War Office organization charged with making scientific and technical decisions. Since no one from Britain had actually seen the aircraft fly, the committee recommended that the military attaché travel to Dayton to view the machine. Following this decision, the Wrights were instructed to expect communication from Colonel Hubert Foster, military attaché to the British Embassy, while Foster was advised to arrange a visit to Dayton. Foster did not contact the Wrights until November 18 when he returned from eight months in Mexico. By this time, Wilbur and Orville were immersed in their experiments of 1905 and negotiations with Britain were not a priority. [43]

The brothers began constructing the third airplane, Wright Flyer III, on May 23, 1905, at Simms Station. During the winter they prepared for the next experiments by conducting engine and brake tests for the new machine as well as readying the parts for the new airplane. They were now ready to begin assembly of the flyer. Several changes were made between the Wright Flyer II and the Wright Flyer III. The wing camber was returned to 1/20, instead of the 1/25 to 1/30 of the 1904 plane. In addition, the plane was slightly longer and taller than any of the brothers' previous planes. A pair of semicircular banes, called "blinkers" were placed between the twin elevator surfaces to prevent the slideslips experienced in 1904. And "little jokers" were placed on the trailing edge of the propellers to halt the deformation observed in 1904.

The most important change was in the control system. Since 1902 the rudder was controlled in conjunction with the wing warping system, but in the Wright Flyer III a separate control was created for the rudder. The brothers hoped this would correct the control problems they had experienced the previous year. With the high hopes that the 1905 testing season would include longer flights, the engine was altered to include oiling and feeding devices to make it safer to run for extended periods of time. [44]

THE WRIGHT FLYER III AT HUFFMAN PRAIRIE FLYING FIELD, JUNE 24, 1905. (Courtesy of Wright State University, Special Collections and Archives) |

During the spring, the brothers had searched for a different flying field that would provide more room as well as greater seclusion. According to Wilbur, "We need a place where we can start at the building and fly in any direction." In response to Wilbur's request for potential locations in Illinois, Chanute replied that he believed the most suitable place would be the flat top of the sand hills at Dune Park in Illinois. Believing Dune Park to be similar to their camp at Kitty Hawk, the Wrights disregarded Chanute's suggestion and committed themselves to once again using Huffman Prairie Flying Field. [45]

For the 1905 season, Wilbur and Orville constructed a new hangar approximately one half mile from Simms Station on the south side of Dayton and Yellow Springs Road. The hangar, like that in 1904, was of frame construction with awning like doors at both the north and south ends. The size of the hangar required that the airplane be taken in and out sideways, for the wingspan was wider than the building. [46]

The new series of tests began on June 23. Over the next twelve weeks, the brothers only flew eight short flights that all ended with a small accident or damage to the flyer. Disappointingly, there was no improvement in the performance achieved with the Wright Flyer II the previous year. With constant repairs and alterations needed on the airplane to improve its performance, Charlie Taylor was often at the Huffman Prairie Flying Field. That summer the Wrights spent their time and energy on the experiments and paid little attention to their bicycle shop. Charlie no longer operated the store but spent his time at the flying field or in the shop constructing replacement parts. [47]

Wilbur, Orville, and Charlie Taylor often rode the DS & U out to Simms Station together. Recalling these rides, Charlie described Wilbur's interaction with women. Charlie found that Wilbur was very friendly with older women when he sat next to them, even offering to carry their packages when they got off the traction car. But, if a young lady sat next to Wilbur, he would get nervous. According to Charlie, "If a young woman sat next to him he would begin to fidget and pretty soon he would get up and go stand on the platform until it was time to leave the car." Summing up one of the reasons why the brothers were not married, Orville once mentioned that he and Wilbur did not have the means to support both a wife and a flying machine. [48]

Milton's fears about injury to one of his sons became a near reality on July 14, 1905. After about twelve seconds in the air, with Orville as pilot, the flying machine began to "undulate somewhat and suddenly turned downward and struck at a considerable angle breaking front skids, front rudder, upper front spar and about a dozen ribs, and lower front spar and one upright." When the plane struck the ground, Orville was thrown violently from the machine. Luckily, he was not injured. [49]

The accident and extensive damage to the Wright Flyer III caused the brothers to make further modifications in the design, and their solution to controlling the machine was in the elevator. When rebuilding the front section of the flyer, they enlarged the elevator and also moved it further in front of the leading edge. According to Tom Crouch, "The aircraft that emerged differed significantly from that of a few weeks before. It embodied all they knew about flying—and some educated guesses." [50]

Returning to their experiments on August 24, the success of the improvements was immediately visible. Yet, rain prohibited many flights. The water did not drain from the Huffman Prairie Flying Field, and many days, even though the sky was clear, the soggy ground hindered any attempts at flying. Wilbur found "The labor of moving the machine on wheels has been greatly increased, and the overexertion produces quick exhaustion, so that only a few flights can be made at a time." Conditions at the flying field did not start to improve until the last week of September. [51]

In the 1905 experiments, Wilbur and Orville attempted to overcome the problem noticed in 1904 of restoring lateral balance after turning or banking. On September 28, Orville, after being in the air for just over eight minutes, passed over the hangar and headed westward across the flying field. As he neared the tree that served as the western turning point in the oval flying field, the plane was at an altitude of fifty feet, ten feet higher than the tree. As he neared the tree, Orville banked to the left to turn and noticed he was headed straight towards the tree. The branches and trunk of locust trees are covered with clusters of sharp thorns, and quite probably caused him to fear the possible results.

In an attempt to try to get the machine to alter its course, Orville shifted his hips in the wing warping control cradle, but the flyer failed to respond. Assuming that the only way to avoid a collision was to land, Orville then lowered the front rudder, or elevator. Surprisingly, the left wing rose and the machine turned to the right, away from the tree, but not before the left wing brushed against a limb. In avoiding an accident, Orville solved the problem faced by the brothers since the 1904 experiments. The remedy was to turn the front rudder down to let gravity supply the extra power needed to maintain control. [52]

By September longer flights without accidents were common, and the Wrights set endurance records with almost every flight. On September 26, Milton witnessed Wilbur fly over eleven miles in just over eighteen minutes. And the minutes in the air continued to increase. Nineteen minutes on September 29; twenty-six minutes on October 3; and over thirty-three minutes on October 4. Orville's flight on October 4 was witnessed by his father, sister, their landlords at 1127 West Third Street the Webberts, and C.S. Billmans, the Secretary of the West Side Building and Loan Company. The brothers' success culminated on October 5 with the longest flight of the year. Wilbur piloted the plane for 24 1/5 miles in thirty-nine minutes. He completed more than twenty-nine circuits of Huffman Prairie Flying Field at an average speed of thirty-eight miles per hour. He terminated the flight only when the fuel supply was exhausted. [53]

The successful October 5 flight was observed by many people. Their accounts of the flight were shared with prospective purchasers of the airplane in the following years and passed down as family stories. Amos Stauffer, a tenant farmer on Huffman's property, was cutting corn the day of the flight. When he noticed the plane rise into the air, Amos commented to his helper that "the boys are at it again." Amazed that the flight continued, Amos quit cutting the corn and walked down to the fence to get a better look at the flying field. Believing the flight lasted for an hour, Amos thought it would never end. [54]

On that same day, William Huffman took the interurban out to Simms Station with his father Torrence. As they left Simms Station, David Beard's son, Torrence, pulled out of the corn field in a wagon. William went and sat on the wagon with Torrence. As the plane completed each of the twenty-nine circles, the boys made a mark on the wagon floor. [55]

With the extended flights, the news began to spread throughout Dayton of the miracle occurring at the Huffman Prairie Flying Field. On October 6, the Dayton Daily News published an article informing the public that the Wrights were making spectacular flights every day. Interest was so great in the Wright brothers that John Tomlinson of the Dayton Journal offered Henry Webbert $50 to inform him when the Wrights planned to make their next flight. The coverage increased public knowledge of the Wrights' experiments and led to an increasing number of spectators. Wilbur and Orville often invited friends to the flying field, such as the Webberts and Billmans who witnessed the October 4, 1905, flight, but many uninvited observers began showing up at Simms Station each day to observe the marvelous invention about which they had heard stories. [56]

1905 WRIGHT FLYER III IN FLIGHT AT HUFFMAN PRAIRIE FLYING FIELD, OCTOBER 4, 1905. |

One of the frequent invited visitors at Simms Station was the brothers' father. In the spring of 1905, the long standing argument of the Keiter issue was finally resolved. In 1903, Milton, ordered to respond to the ruling of the hearing or face possible suspension, had ignored the ruling in Keiter's complaint against him. The General Conference of 1905 was the first meeting of the church where action could be taken since the conferences were only convened every other year. The delegates to the General Conference upheld the bishop by a two-thirds majority. Milton was finally cleared in the matter, but he was also retired from all duties in the church. Milton's long association with the church had come to an end, and this left him with more free time in which he could observe his sons' experiments. [57]

The Wrights discontinued their flights until the number of spectators decreased. While Wilbur and Orville felt that their experiments were nearly completed, they hoped to make a flight of an hour duration before the end of the season. Notifying Chanute of their intent, they also mentioned, "If you wish we will try and give you notice in time for you to be present." Chanute had not witnessed any of the Wrights' flights except for the short flight of October 14, 1904, and the brothers believed Chanute would be a valuable witness of their flights to potential clients. [58]

Wilbur and Orville resumed flights on October 16, when Wilbur made a flight that was cut short due to engine trouble. Hoping that Chanute could witness what they anticipated would be their longest flight, Wilbur cabled him on October 30, "Trial Tuesday. Can you come?" Chanute departed Chicago that night to arrive in Dayton in time for the flight. Unfortunately, the flight never occurred because of a storm. The 1905 season ended with the October 5 flight as the longest of the year and Chanute missing the opportunity to witness a significant flight. [59]

With the record-breaking flights of September and October, the success of the Wright airplane was proven. Their comprehension of the solution to the problem of flight had reached a point, with the Wright Flyer III, far beyond any previous contemporary experimenters of their day. The Wright Flyer III was their most sophisticated machine to date and was the world's first truly practical airplane. A significant design difference in the 1905 Wright Flyer III was the use of independent rudder and wing warping control. The Wright brothers had full three axis-control of pitch, roll, and yaw, each independent of the other. The sustained flights and technological advancements of the Wright Flyer III were as important achievements as the famous first flight on December 17, 1903.

Six years after beginning their aeronautical experiments, Wilbur and Orville Wright succeeded in conquering the age-old question of human flight. Now that they had a marketable product, the brothers chose to quit flying. With the time, energy, and money invested in their invention, they did not want to just hand the technology to the world. Without a patent to protect the flying machine and no impending sales, the brothers chose to discontinue flights and market their product. [60]

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

daav/honious/chap7.htm

Last Updated: 18-Feb-2004