|

Denali

A History of the Denali - Mount McKinley, Region, Alaska Historic Resource Study of Denali National Park and Preserve |

|

Chapter 7:

THE PIONEER PARK

Recall that Congress had rested on its laurels after enactment of the park legislation in 1917. For more than 4 years McKinley was a park in name only—unfunded, unmanned, unprotected. Finally—after many petitions from conservationists, the Governor of Alaska, and Interior Department and NPS officials—Congress appropriated $8,000 for the fiscal year beginning July 1, 1921. Increased market hunting and poaching, paired with the threat posed by the approaching railroad, had jolted Congress to take the first step in carrying out its own statutory mandate: to preserve the park as a game refuge.

By then the name of Henry P. Karstens headed the list of those being considered for the job of park superintendent. Karstens had broached the subject in a 1918 letter to NPS Assistant Director Horace Albright. This was the letter, solicited by Albright, that established Charles Sheldon as the originator of the Mount McKinley National Park idea. In describing Sheldon's concept of a park that would protect Denali's game, Karstens stated: "One thing which brings it home to me is, Sheldon promised to assist me to get the Wardenship if it went through." [1]

|

| Henry P. (Harry) Karstens, first park superintendent, 1921-1928. Charles Sheldon Collection, UAF. |

In this same letter Karstens expressed irritation with Alaska Governor Thomas Riggs, who " . . . tried to tell me that he was the man that proposed the park." Not only did Riggs disbelieve Karstens as to Sheldon's role, he also tried to talk the Sourdough out of applying for the superintendent job. Karstens continued:

I was thinking it over for a day or so when I found out that Mr. Raybourn [W.B. Reaburn], one of Riggs' men [on the Alaska-Canadian Boundary Survey] had made a special trip out to Washington to put in his application. Raybourn is a fine man & if I cannot have the position I hope he gets it.

Almost 3 years later Governor Riggs still favored Reaburn for the job. At the request of NPS Director Stephen T. Mather, Riggs evaluated candidates for the superintendency, dismissing all but Reaburn and Karstens from consideration. His profile of Karstens was prophetic:

Harry Karstens is an excellent man and perhaps deserves consideration for the fact that he made possible the ascent of Mt. McKinley for the Stuck party. He is a good woodsman and thoroughly energetic. If it were not for Reaburn I should give serious consideration to Karstens. He is not, however, any where near the equal of Reaburn, as he is very independent and would be apt to tangle up with the authorities the first time there should come a little disagreement. In the appointment of Reaburn I know that you would make no mistake, whereas if Karstens should be appointed there might at times be friction not only with your office but with visitors to the park. I know that Charlie Sheldon will go to the mat for Karstens and if I were in Sheldon's place I would do the same thing. [2]

Mather noted with concern the governor's fears that the feisty Karstens would cause problems for the park and the Service. But Charles Sheldon's previous sponsorship of Karstens had already elicited Mather's all but unbreakable commitment to the Founding Father that "There is no question in my mind about Karstens being the man for the place . . . ." [3]

Governor Riggs certainly suspected that such a commitment was already made, for Mather had earlier told him of Sheldon's high recommendation of Karstens for the pioneer superintendency. [4]

As Karstens' 7-1/2-year administration of the park progressed, Mather would have ample reason for rueful pondering of Riggs' warning. Karstens' superintendency would fall into two arenas: 1) the true pioneering of a wild and undeveloped park—in which he excelled, and 2) the bureaucratic and public-official aspect—in which Karstens' direct-action approach often produced conflict at the park and distress among his Washington Office mentors who were trying to coach him along the path of prudence.

In the early years, with the focus on dog-team patrols and the hewing and laying of logs for park buildings, Karstens' rough-and-ready manner fit the park's needs like a glove. Later, when the finesse skills of interagency cooperation, resolution of disputes with park neighbors, and fiscal and personnel management became the paramount needs, Karstens—despite his own earnest efforts and the sympathetic counseling of Assistant Director Arno B. Cammerer—could only partially make the transition.

Nor were Karstens' troubles entirely of his own making. There were some hard cases out there, people who practiced calculated provocation to bring out the old Sourdough in him. After an explosion, they would write letters to Juneau and Washington officials misconstruing events and exaggerating Karstens' responses to them.

In sum, Karstens would be a pioneering hero part of the time and a man who outlasted his greatest usefulness part of the time. But he did well the two most important tasks of his charge: he all but stopped the poaching that was eroding the park's vulnerable wildlife, and he completed, largely with his own hands, the park's first-stage development that made it an operating unit of the National Park System. On balance, his strengths as pioneer superintendent outweighed his flaws as prudent bureaucrat.

On April 12, 1921, Director Mather sent a 10-page letter of instructions to Harry Karstens, formalizing the multifaceted charge that Karstens took on with Mount McKinley's superintendency. Much of the letter shows the hand of Arno B. Cammerer, Mather's administrative right hand and patient mentor to Karstens. But aside from details about Karstens' interim appointment as ranger-at-large until funds came on July 1, accountability of funds, budget preparation, and the like, the letter's substance was pure Mather. Taking into account the mining and hunting compromises that burdened the park's establishment act, Mather noted that special regulations adjusted to these factors would soon follow. Karstens would apply general and specific NPS policies at Mount McKinley with " . . . tact, good judgment, firmness, fearlessness, and a cool head at all times." He would proceed gradually with enforcement—explaining and warning before charging and arresting. All persons, whether permanent on the land or visitors, would be treated with respect and courtesy. Violators of the law—poachers and trespassers—would be removed with only such "violence as may be necessary, with an admonition not to repeat the offense." Karstens would get to know park neighbors, officials in other agencies, the U.S. District Attorney in Fairbanks, and potential concession operators who could provide services to visitors. He would canvass local people to find a suitable man for assistant ranger. And he would report his work regularly to the Director. [5]

This would be a ticklish business. Karstens would stand alone in this huge and totally undeveloped wilderness park, itself nested in a vast surround of wildness. He would bring with him a public lands philosophy still new in the States and completely alien to Alaskan attitudes and experience. Likewise new and alien were the laws and regulations with which Karstens would apply and enforce that philosophy. Of local precedent and backup he had none. Steve Mather concluded his letter to Karstens with the promise of all possible support from Washington. Then he said with somber understatement, "The rest is up to you." [6]

The core of the Service's philosophy derived from the Yellowstone National Park Act of 1872 and the National Park Service Act of 1916. Horace Albright, with the aid of the Nation's leading conservationists, had translated these graven statutory tables into a letter setting forth the policy objectives and management principles that would govern the Service. On May 13, 1918, Interior Secretary Franklin K. Lane sent this letter to NPS Director Mather, thus formalizing the Service's charter.

The chief principle was that "Every activity of the Service is subordinate to the duties imposed upon it to faithfully preserve the parks for posterity in essentially their natural state." Only those commercial activities specifically authorized by law or permitted for the accommodation and pleasure of visitors would be allowed. In its own planning, development, and operations the Service would avoid the inroads of modern civilization so that unspoiled bits of native America could be experienced by present and future generations. Where improvements were necessary, they would be designed to harmonize with the landscape. Hunting, timbering, grazing, and other consumptive uses would be disallowed or phased out, consistent with law. Private inholdings, especially those seriously hampering the administration of these reservations, likewise would be phased out over time by purchase or donation. [7]

Armed with such notions, Karstens surely had his work cut out for him. Alaskans were used to using at their pleasure the whole spread of the essentially unsupervised public domain, which constituted all but a few parcels of Alaska's huge territory. Now someone, albeit one of their own, would be telling them to "stop and git," and arresting them if they didn't. Karstens' first imperative was to protect the park's wildlife. This was policy. In the Director's Annual Report for 1919, Mather had informed the Secretary and the Congress that:

It will not be the policy of the National Park Service to immediately open this park to tourists; in fact, several years may elapse before any program for developing the scenic and recreational features of the park is adopted. We are interested now only in the preservation of the caribou, mountain sheep, and other animals that make this region their home . . . . [8]

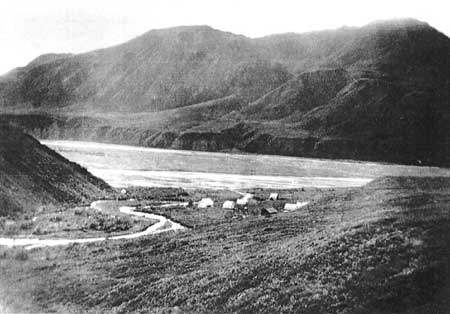

To protect the park Karstens needed a base camp accessible to both the railroad—his line of access and supply—and the park itself. McKinley Station on the railroad near the Riley Creek-Nenana River junction had to be the location, for it was the topographically determined entrance to the park. The original configuration of the park placed its nearest boundary some 16 miles west of McKinley Station. Even after Congress extended the park to within 3 miles of the station on January 30, 1922, Karstens had to secure an administrative corridor to assure his unhampered access to the park and an entrance for "a main artery road through the upper passes," which Karstens cited in his June 1921 report to the Director as "the park's most urgent need."

Eventually, executive orders gave him the corridor and land upon which to build his base camp, but not before the expenditure of much blood and sweat over strategically placed homesteads that temporarily blocked his plans. From this base camp—with its cabins, barns, and kennels—Karstens and his men (when he got them) could range the boundaries and the choice hunting grounds, tracking, warning, and, if necessary, arresting wrongdoers.

After a summer 1921 swing into the park with pack horses—touching bases with his old Kantishna comrades and explaining the park and its regulations—Karstens began to scrounge, beg, and borrow tools and materials for the base camp. He made a deal with Pat Lynch, who agreed to relinquish his homestead on Riley Creek at the south end of the railroad bridge, so Karstens had a place to build. This site had been used by the AEC for its Riley Creek-bridge construction camp. From this and other abandoned camps, Karstens salvaged buildings and equipment for his own camp. This location in the creek bottom was Karstens' second choice. He wanted to be on the high ground on the same level as the railroad and the station. But Maurice Morino's homestead and roadhouse complex occupied all of that ground, and difficulties between the two men produced an impasse. The AEC, trying to secure its own right-of-way and administrative site on the Morino property, distanced itself from Karstens during this time to preserve good relations with Morino. It was a pretty tangle that caused Karstens sleepless nights and provoked long letters to Washington officials and Charles Sheldon.

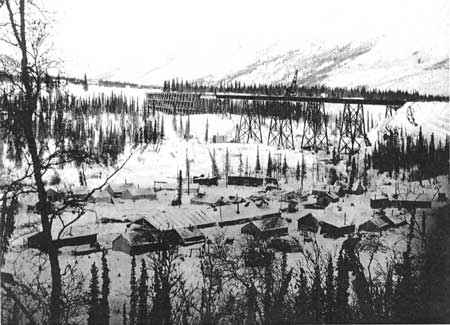

|

| Riley Creek bridge construction camp, during the winter of 1921-22. Alaska Railroad Collection, AMHA. |

Karstens' ad hoc deals, his loan and salvage arrangements with the AEC, his commitments to Nenana storekeepers for essential supplies—all necessary acts to get the park going—threw the auditors in Washington into a tizzy; but Cammerer understood, calmed the auditors, and continued to coach Karstens on the procedures that would let him proceed, yet keep the accounts and administrative proprieties straight. The correspondence between the two men followed a cycle something like this:

Karstens: Wait 'til I tell you about this one.

Cammerer: Harry, I know you had to do it, but next time do it this way.

Karstens: Thanks, Mr. Cammerer, I sure won't do that again, and by the way, what do you think of this deal I just pulled off? [9]

Thus, by hook and by crook Karstens could report these accomplishments after a year on the ground:

A Superintendent and assistant were provided for. Two dog teams of five dogs each with harness, sleds and equipment for winter operations; also three horses, harness, bobsled, wagon, and horseshoeing, blacksmith and harness repair outfits with necessary equipment were acquired.

Base camp was established at McKinley Park Station on the Government railroad, where a portion of land one mile wide extending into the park was set aside for entrance and administrative purposes.

The superintendents dwelling and office were built at this point with barn, storehouse, workshop and necessary out buildings. [10]

Already the plan to protect first and do other things later had gone awry. Karstens had too many things to do all at once. He oversaw the park boundary survey and marked the line with boundary signs. Lands issues had obtruded, as had the building of the base camp, which was prerequisite to any substantial and steady in-park operation.

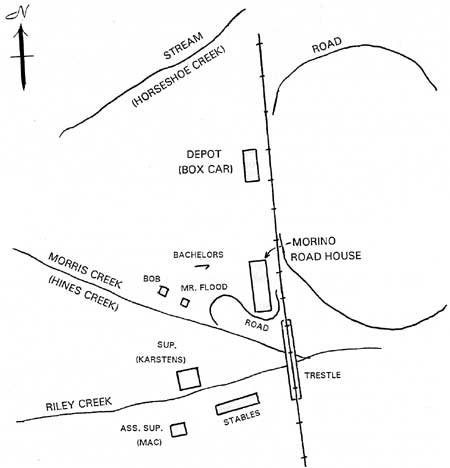

|

| This is the only known map of the early (1922-25) park headquarters area. The map was sketched during the 1970s, showing conditions as they appeared in the summer of 1923. George Flood, a horse packer, and Bob Degan both worked for concessioner Dan Kennedy during his first year of operation; they resided in adjacent cabins along Hines Creek. The NPS took up residence along Riley Creek; the only two employees that summer were Supt. Karstens and Ranger E.R. McFarland. (Flood apparently thought that McFarland served as assistant superintendent.) The map is redrawn, and is not to scale. Drawn from the memory of George Flood, in DENA archives |

Getting supplies into the park and selecting tent or existing cabin sites for patrol shelters also had to be done first. Deploying the supplies, erecting tents, cutting and transporting wood fuel, repairing abandoned cabins (after checking with locals whether they were abandoned, or if the builders had any rights to them)—all these things, too, had to be done first, if ranger patrols were to be anything but easily eluded charades.

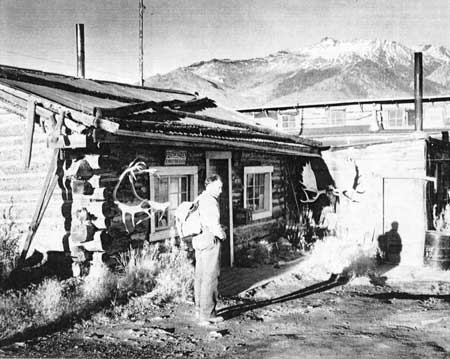

|

| Squatter's cabin near the park headquarters, ca. 1930. "MIscellaneous MOMC" file, AMHA. |

As a first step toward maintaining the NPS presence inside the park, Karstens and his assistant ranger pioneered a wagon road 12 miles along Hines and Jenny creeks to Savage River. On this rough track they conveyed a ton of supplies drawn by a four-horse team, then established a cache and supply point for interior-park patrols. [11]

The intent to deal with visitors later, after first things had been done, went against the old saying: Time and tide wait on no man. Imminent completion of the railroad forced the issue. Tourism promoters, shipping lines, railroad officials, and boomers and boosters in various Alaska towns were already advertising tours by ship, steamboat, auto, and railroad. Mount McKinley National Park ranked as the prime objective of this grand loop through the Interior.

Potential concessioners crowded Karstens' office with schemes for hotels and transportation systems into the park. Much correspondence ensued between the park and Washington to evaluate these proposals. And the concession candidates were less than loath to contact the Governor and the Delegate to Congress in their pursuit of monopoly rights within the park. This, too, required correspondence.

The proposed main road into the park, the one the ARC would build for the NPS, tied directly to the concession proposals. For, lacking the road, all but the hardiest visitors would be left standing and fuming at the station waiting for the next train. [12]

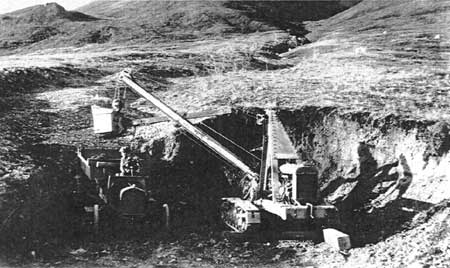

While Karstens labored to create a rudimentary park administration and operation, the ARC moved forward on park-road construction. Col. James Steese of the ARC had outlined the dual park and commercial road project in an April 1922 letter to Director Steve Mather, conditioned upon NPS provision of funds and design control. [13] Mather's acceptance sealed the agreement and spurred the ARC's route survey and erection of shelter tents and trail markers clear to Kantishna that summer. From 1923 to 1938, the ARC gnawed away at the road project: 2 miles in 1923, 5 or 10 miles each succeeding construction season, depending on terrain and funds available in the Service's park-road account. At each construction camp the ARC built a standard-plan 14-foot by 16-foot log cabin that served as cook house in summer and storage cache in winter. Work-crew tents clustered around the cabin, forming the season's home camp, which would move on westward with construction progress. [14] As camps were abandoned, the cabins could be used as ranger-patrol shelters. Several of these ARC cabins survive today as ranger stations along the road. Also still used are similar patrol cabins of the 1920s-30s, built by the rangers at strategic points along the old park boundary.

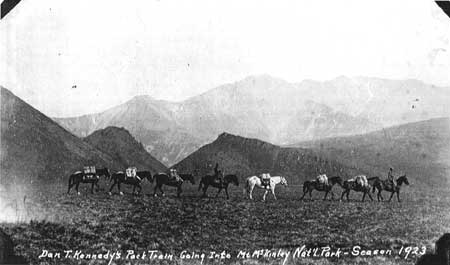

By end-of-season 1924, the road was passable for buses and touring cars out to Savage River, 12 miles from McKinley Station. [15] The primitive concessioner tent-camp there, operated in 1923-24 by horse-packer Dan Kennedy, was taken over and improved by the Mt. McKinley Tourist and Transportation Company under Robert Sheldon's management (no relation to Charles Sheldon). The 1925 tourist season recorded the first significant visitation into the park, 206 persons vs. only 62 in 1924. The company's four touring cars had trouble at times handling visitor traffic between McKinley Station and Savage Camp.

|

| Dan Kennedy was the park's first concessioner. |

|

| The Mt. McKinley Tourist and Transportation Company took over from Dan Kennedy in 1925. It retained park concession rights until the eve of World War II. AMHA. |

The camp itself became a "tent house colony" during the summer. Dining hall, social hall, and tent houses took care of some 60 people at a time. Barns, a corral, and utility buildings completed the camp, which was served by running water.

From this base, visitors could proceed on horseback, and later by Concord stages, on various loop trails into the Savage and Sanctuary rivers country. Spike camps allowed overnight wilderness experiences. More adventurous visitors could take guided pack-train trips into the park's farther hinterlands.

By 1928 the company had progressed westward along the ever extending road and beyond, on the grubbed out trail that marked its future course. Smaller camps at Igloo Creek, Polychrome Pass, Toklat River, and Copper Mountain (renamed Mount Eielson in 1930 for bush pilot Ben Eielson) hosted those who sought the more primeval spaces. By 1929, the company's 22 buses, 9 touring cars, 4 stages, 2 trucks, and a trailer were pressed to the limit to handle visitors and logistics. At that, with only 150 or 200 visitors in the park at a given time, this was the golden age of park touring: the festive train ride and arrival at McKinley Station, the lined up buses and touring cars, the scenic drive into the park, with welcoming arrival at various camps. Here amidst rustic but comfortable settings (and at Savage quite civilized dining and dancing) visitors could choose amongst many treks by horseback, packtrain, and stage that took them into Mount McKinley's wildlife and scenic splendors. [16]

|

| A Yellowstone stage at Savage Camp. The social hall, adorned with a moose rack, is at the right. Herbert Heller Collection, UAF. |

But, as the Superintendent's Monthly Reports reveal, all was not rosy. Karstens spent inordinate time monitoring both road construction and concession operations. Disputes between him and the road engineers over clean-up of construction debris, micro-choices of route and design to meet the "park ideal," and management of NPS funds kept the air and the wires humming. Depending on the tourist-camp crew make-up, Karstens had some good years and some bad years. Once the proximity of game tempted nimrods on the crew to poach. Sometimes rates or food and sanitation standards departed from concession-contract terms. But all in all, the park had become a legitimate and much enjoyed objective for tourists.

Despite the increasing pace and strain of his work, and as a part of his charge to win the hearts and minds of Alaskans, Harry Karstens took every opportunity to express his poet's love of the park. On one of his business trips to Anchorage he addressed the Women's Club on the park's progress, ending with this peroration:

A natural park is being preserved in its naturalness for you and for me and for our children—unspoiled, unmarred. To enjoy this "pleasuring ground for the benefit and enjoyment of the people," its sublimity of beauty and grandeur, one must be in tune with these things. There is little to offer visitors who need attendants to make them comfortable, who think of walking in terms of cement and board paths, riding in terms of cushioned motor cars, who cannot appreciate a forest unless it is manicured or enjoy animals that have never felt the touch of the hand of man and do not wish it, who would be annoyed by noisy squirrels and gophers and whistling marmots and myriads of ptarmigan, hordes of rabbits, who would become hysterical about a few insects or faint and panic stricken if they missed a meal or two. Neither is there much consolation for the one who is prone to indulge in the pompous manner and the arrogant word.

But there is much to offer those who understand the language of the "great silent places," the "mighty mouthed hollows, plumb full of hush to the brim." To the hardy, venturesome ones there are heights to be scaled where bands of sheep and herds of caribou look with wonder and curiosity at the traveler. There are noisy mountain and glacier streams, noble crags and precipices, master pieces of nature's rugged architecture that have never yet been photographed. There are glaciers to cross. There are mountains to climb, from the easily ascended near-by domes to the dizzy peaks amid the everlasting snows. Eagles will be seen soaring about their breeding places among the pinnacles on the jagged sky-line.

Mount McKinley National Park has an abundance for each and everyone. Here will be found an indescribable calm; a place to just loaf; healing to the sick mind and body, beyond reach of the present day mental and nervous and moral strain. [17]

One of Karstens' most important acts as superintendent was relocation of the park headquarters in 1925. The base camp on Riley Creek below the railroad bridge was inconvenient, a second-choice location from the beginning determined by the Morino homestead, which occupied the best ground around McKinley Station. Moreover, in winter the frigid air sank into the creek bottoms making them 10 to 15 degrees Fahrenheit colder than nearby benchlands. The difference between -45 degrees and -60 degrees is profound and potentially lethal. Colonel Steese had helped Karstens out some by giving him office space in an ARC building at the station. But the families of Karstens and his staff, and the park's horses and dogs benefitted not at all from this partial solution.

In February 1924 Karstens wrote to the Director:

Owing to the survey and part construction of a road from the Alaska Railroad at McKinley Park station through the strip of land set aside by Executive Order for Park purposes, to the Eastern boundary of the Park, I believe it is time to take up the question of moving our headquarters from its present location to a point along this road. There is a beautiful spot, with ample room for expansion, one and two-third miles from the railroad, which is not within the boundary of the Park proper but is on the land temporarily set aside by Executive Order dated January 13, 1922.

I wish the Service would advise me if I could build headquarters on this land, and if I could expend Park funds (if available) on such work. My idea is to make this a permanent location, plotting out the site with a view to future development and adequate sanitation. Such buildings as we can construct will be built of logs, having an eye to their permanency and attractiveness, and also for warmth and comfort. Building headquarters at this point will simplify the work of checking persons entering the Park or leaving it. The present location is very unsatisfactory in this respect. [18]

After several exchanges of correspondence on the relocation Karstens' old friend, Acting Director Cammerer, ratified the new headquarters site and coached him to proceed promptly with construction of "temporary" buildings even before appropriated funds became available:

There has been one point that you have mentioned here and there in preceding correspondence and that is the possibility of establishing park headquarters farther on in the park, or near the park boundary. I am fully convinced that such a move is very desirable from an administrative standpoint and for other reasons, particularly now that the new road into the park is being developed. You should, therefore, bring with you to Seattle a map showing the proposed location of such new administrative headquarters, and you should include in your supplemental estimates an amount sufficient to construct a few permanent buildings, adequate in size and design for permanent construction. Of course, if headquarters is established before funds for such buildings will be available, as I expect will be case, it will be necessary for you to establish in temporary living headquarters, such as you are now living in at McKinley Park Station, temporary structures. [19]

Karstens and his rangers moved rapidly. They dismantled several structures at the Riley Creek base camp and built, largely from the salvage, three one-room log cabins, a barn, and other utility shelters at the new headquarters site. This small, park-like plateau, girt by mountains, with a cover of white spruce and willow, lay in the angle between Rock and Hines creeks. At an elevation of 2,000 feet above sea level and 600 feet above McKinley Station, the headquarters benefitted from the warm-air inversion typical in winter. It offered a stunning view down the Hines Greek fault and across the Nenana River to the alpine peaks that rim the Yanert drainage.

In time, with the efforts of Karstens and his crew—and the work of successor superintendents Harry Liek, Frank Been, and Grant Pearson—the headquarters complex of the early Forties gave the park a first-class administrative, residential, and utility base, including stables and kennels for pack and patrol animals. Together with the patrol and boundary cabins (15 in all built by 1939), and the ARC cabins along the road, the park boasted an operational plant that, with a few additions in the 1950s, proved adequate until the advent of highway access in 1972. [20]

Karstens' headquarters locale would be challenged in 1929, when Chief Landscape Architect Thomas G. Vint visited the park to initiate the first professional planning effort. He thought the headquarters should be moved back to McKinley Station. But Director Horace Albright, knowledgeable about cold and wind from his Yellowstone superintendency days, vetoed any shift back to the low, exposed country along the railroad. When Albright visited the park in 1931 he said the clean and well laid-out headquarters area, with its sturdy and handsome log structures, compared favorably with any park headquarters in the States. He described it as ". . . a distinct credit to the Service, and an important asset, as it is seen by all tourists as they go down to visit . . . the dog kennels." [21]

Today the log buildings built by Karstens and his successors comprise a functional registered historic district still used for administrative and residence purposes by the Service. Visitors still enjoy this rustic period-piece as they wander through it on the way to the kennels and dog-sled demonstrations.

Despite plans for staging, things had happened "all at once" from the beginning at Mount McKinley National Park. Aside from setting up physically to manage the park, Karstens had to have a charter of authority, adapted to the statutory provisions that, among other things, protected valid mining claims, allowed new-claim entries under the mining laws, and gave prospectors and miners operating within the park the right to:

take and kill therein so much game or birds as may be needed for their actual necessities when short of food; but in no case shall animals or birds be killed in said park for sale or removal therefrom, or wantonly. [22]

These provisions, the price of getting the park bill through Congress, and particularly the hunting exception, caused immediate foreboding among the Founding Father conservationists, Washington officials of the Park Service, and Harry Karstens himself. John Burnham of the American Game Protective and Propagation Association, in late 1920, coordinated the efforts of his organization, the Boone & Crockett Club, and the Camp Fire Clubs to pay for weatherproof posters to be placed in the park quoting the Congressional proscriptions on hunting. Early in 1921 Burnham and his associates drafted suggested regulations for the park that emphasized the Interior Secretary's legal obligations under Section 5 of the park act to regulate the taking of game to assure its protection. The draft regulations would empower the park superintendent to confiscate game killed, along with the hunting outfits of violators of the Congressional proscriptions. They also provided for fines and imprisonment of those convicted. [23]

In April 1921 Assistant Director Cammerer sent to Karstens the Park Service draft regulations, which included much of the Burnham material, plus pen-and-ink comments solicited from Charles Sheldon, who wanted Karstens to review the regulations. All of Sheldon's suggestions concerned the hunting issue. Paramount was the need for a permit system that would enable the superintendent to distinguish real prospectors miners from the poachers and market hunters who posed as such.

In forwarding the draft and comments to Karstens, Cammerer stated that the

act creating the park was particularly specific in giving miners and prospectors all possible leeway in pursuing their work, and I think they are permitted to go in without a permit; in other words, it would be difficult to enforce a permit clause if a miner decided not to apply for it. [24]

Cammerer sought Karstens' best thought on this issue, which came in a quick reply to the Director just before Karstens embarked from Seattle to start his new job at the park. [25] He strongly endorsed the idea of a permit system to control both hunting and timber cutting in the park. As an added benefit, the permit system would require face-to-face contact with permittees, giving Karstens a chance to explain the park rules to them. He said, "Alaskans as a general rule try to be law abiding in everything except hunting, and in that they think they have a perfect right to game—and wherever they want it." Karstens plugged for a regulation requiring prospectors and miners to keep a record of game killed so he could judge if they were hunting only when truly necessary, as Congress intended. He agreed with Sheldon that there should be no exception to confiscation of violators' game and outfits, for ". . .confiscation would have a tendency to keep wrongdoers out of the park." Differing from Sheldon, Karstens would allow miners to feed game meat to their dogs if the alternative were killing the dogs, for local fish were poor and supplies out of reach in hardship conditions. He believed that Toklat-Nenana Indians, who usually ran out of their dried and smoked fish by spring, had a special claim to survival hunting in the park up the Toklat's forks; and for the same reason, Birch Creek Indians of the upper Kuskokwim sometimes were forced to get a few caribou and moose in the park near Kantishna. (On the last, Cammerer in a letter of May 4, 1921, granted that this was a delicate issue and gave Karstens leeway to use his own judgment.)

As finally issued on June 21, 1921, the special regulations for Mount McKinley National Park avoided the permit issue, but required that prospectors and miners keep records of game killed, open to examination by the superintendent. Killing game principally for dog food could occur only on the condition of an advance permit from the superintendent, but excess meat left over from human food could be fed to dogs without a permit. Confiscation of violators' game and outfits was affirmed. Other provisions relating to miners and prospectors working in the park (e.g., carrying guns without a permit; using dogs for transportation and packing) reflected standard Alaska practice. [26]

The patchwork nature of these regulations, the ambiguities dictated by law, and the near impossibility of nailing down a prosecutable violation, especially in Alaska's social environment, are obvious. As park proponents feared, it was the hunting provision more that any other that would plague the park's administration and preservation. Letters of complaint about wanton killing of park game from conservation luminaries such as Dan Beard, Sr., [27] vied with inquiries from the mining constituency, such as the interrogatory from J.A. Davis of the Bureau of Mines Experimental Station in Fairbanks. [28] Davis wanted clarification of the regulations to guarantee the miners rights to work and hunt in the park in a way that would aid the mining enterprise—including use of timber, water rights, construction of ditches and dams, etc. But always the hunting provision and its abuse by some miners and a hard core group of dissembling poachers and market hunters grabbed the spotlight.

The latters' numbers increased under cover of the Kantishna mining excitement in the early Twenties. This got the attention of the joint National Parks Committee of the Nation's leading conservation organizations. The minutes of the committee's meeting of April 17, 1923, quote a resolution urging the Secretary of the Interior and the National Park Service to take all necessary action to control hunting at McKinley, and calling on Congress to increase appropriations for wardens to enforce the controls. [29]

In his 1923 Annual Report to the President, Interior Secretary Hubert Work decried the miners' wanton killing of game in the park for themselves and their dogs. He asserted the need for amendatory legislation to repeal the hunting provision of the park act. [30]

Even the Pathfinder of Alaska, after isolating the renegade few from the majority of law-abiding prospectors and miners, conceded that if Mount McKinley's game was in fact being destroyed as reported by the Secretary, ". . . he is right in taking steps to put a stop to the practice," for the one place where plentiful wildlife "should be saved is in a National Park." [31]

The Secretary's idea of legislative repeal got locked in after he received his solicitor's opinion that—as Cammerer had earlier stated to Karstens—the park's legislative history did not support the Secretary's explicit regulation of hunting by prospectors and miners. The solicitor cited the settled rule of law, which states that if a right is granted by statute (in this case the park's establishment act) it cannot be abridged by the regulations of an executive department. [32]

The Service's Washington Office and the park tried all manner of expedients to restrict park hunting to actual necessity, as Congress intended. But these efforts fell far short. Reports of renegade trappers in the McKinley River drainage added to the concerns over wildlife destruction. Pleas to Congress for funds for more rangers went unheard. [33] In cooperation with the U.S. Biological Survey, by now in charge of Alaska Game Law enforcement, Alaska Game Wardens were appointed without pay as park rangers, and rangers were deputized as wardens. [34] Still, the park's vast spaces and the law's vast loophole defeated the objective of preserved wildlife.

In early 1924 biologist Olaus Murie of the Biological Survey, then studying caribou in the park, reported to his boss, Dr. E.W. Nelson, that the future of the park's game was really endangered. [35] About the same time Karstens wrote a long letter to the Director citing many hunting depredations—sled loads of meat being transported out of the park by men who maintained that everyone else was killing animals where and when they saw fit. It was impossible for Karstens, often away on public business, and his one assistant ranger to cover even the near hunting and exit sites, much less the far reaches of the park. He concluded:

My recommendation would be to close the park to all hunting. As long as prospectors are allowed to kill game, just as surely will the object of this park be defeated. Any townie can take a pick and pan and go into the park and call himself a prospector. This is often the case. Compromises will not do for compromises only leave loopholes for further abuse. [36]

Karstens' letter, along with the other reports that documented wholesale killing of park wildlife, inspired Washington officials to call together leading conservationists—Dr. Nelson and Olaus Murie of the Biological Survey, John Burnham of the Game Protective Association, and Charles Sheldon—to develop with the Service a strategy leading to repeal of the park-act hunting provision. During the course of this meeting Director Mather made the point that ". . . the United States was planning to put some $275,000 into new road work in Mount McKinley Park, and that any depletion of the wild life would be bound to have an adverse affect on the visitors, who, seeing the Mount McKinley National Park as the chief scenic asset of Alaska, would expect to see some of the wonderful caribou herds and flocks of sheep . . . ." He urged all present to make the point with Alaska Delegate to Congress Dan Sutherland that these visitors, potential settlers and investors, ". . . would do more toward developing Alaska's resources than any other possibilities to which Alaskans could point to build up their territory." [37]

Eventually, as a result of mounting conversation pressure and the perversion of the open-ended hunting provision that could not be regulated, Congress repealed it by an amendatory act approved May 21, 1928. The same act opened the way for more rangers by lifting the $10,000 annual appropriation limit imposed by the establishment act. [38]

In a related effort initiated by Director Albright, Congress in 1931 granted the Secretary explicit authority to regulate surface use of mineral land locations, and to require the registration of all prospectors and miners entering the park. [39] But not until 1976 were new-claim entries under the mining laws prohibited in McKinley Park. [40]

Slowly, structural changes and adjustments of law to make the park administrable were taking place. Meanwhile, Karstens and his rangers carried on their work—patrolling, stopping wrongdoers, making friends or enemies as occasion demanded, and, as a by product, establishing an enduring Park Service tradition in Alaska.

As a Sourdough himself—Klondike stampeder, hunter, dog-driver, mountaineer—Karstens set the tone for that tradition. When Grant Pearson came to work for him as a buck ranger in 1926 he knew he was in the presence of a living legend. [41] Pearson, who would become McKinley's superintendent and a legendary outdoorsman in his own right, never lost his affection and admiration for Karstens. Even after the troubles that drove Karstens from the Service, Pearson held that the government ". . . couldn't have chosen a more competent man to pioneer the initial development" of the park. [42]

Pearson's recall of his testing days as a new ranger paint a picture of early park conditions and Karstens' demanding standards:

Henry P. (Harry) Karstens, first park superintendent, 1921-1928. Charles Sheldon Collection, UAF.Superintendent Karstens certainly did not like government red tape, especially when he was of the opinion that it was necessary to discharge an employee. Quite often when some of the personnel became angry with him, he preferred to settle matters outside the office with their fists, rather than prefer official charges. That situation eventually led to his downfall in government work.

During the three years I worked under the supervision of Karstens, I found him to be very fair and considerate. I made several long trips into the back country of the Park with him and he taught me many original ways of getting along the trail.

On several occasions during the time I was at the park Karstens actually came to blows with some of the park personnel, and I never knew him to come out second best.

Considering that he was in a frontier area, he was a realistic administrator. Those were the days when a Ranger was not required to pass a Civil Service Examination. He had his own system, and considering the type of duties a Ranger was required to perform, his system certainly weeded out those who were unfit for the job. When I talked to Karstens about a Ranger's job, he asked me a number of questions about my experience as a woodsman and wilderness man.

I shall never forget that, when he got through asking questions, he said, "You're lacking in experience, but I think you can learn. I'll send you on a patrol trip alone. You will be gone a week. If you don't get back by then, I'll come looking for you, and you had better have plans made for a new job. Now this is what I want you to do." He then outlined a week's patrol trip cross-country through territory new to me. There were no blazed trails to follow. One could follow only the terrain cross-country. He also gave me a rough map and much valuable advice. No reliable maps of the Park were available in those days.

Karstens said, "This will be a trial trip, and real test for you. We can't use anyone on our Ranger force who can't take care of himself in the wilds.

The Ranger you are replacing was unfit for this service. We sent him out on the same patrol you are going to make and he returned in a most pitiful condition. He just staggered back, almost starved. The poor fellow was gone for three days and couldn't find the patrol cabin. He hadn't eaten a hot meal since he left. His reason was that he couldn't find any water that wasn't frozen to ice. The ground was covered with snow. He had a trail axe and could have cut some dry wood and melted ice or snow for water. Luckily the weather was warm, about zero and he didn't suffer any frostbite.

When this fellow took the job he said he had had plenty of experience out in the wilderness by himself. This trip you are making isn't too tough. However, it is the kind that separates the glamour boys from the type we can use in our work. [43]

Karstens never rested on his laurels. He got into the park whenever his administrative and public-relations duties allowed. And when he left town or office for the trail, he did more than tour. Often he traveled alone on long dog-team patrols, siwash camping in the woods as in the days before cabins. Whenever he went out, he did something that set an example for this men, whether it was long hours tracking a violator or building a patrol cabin with his own hands. He did this, too, because out there, off the beaten path, he was the happiest of men. [44]

The rangers who survived Karstens' weeding process—stalwarts like Fritz Nyberg and Pearson, and the temporaries who helped them—built a rangering record that made Mount McKinley the Yellowstone of the North, the operational academy for Alaska park rangers. That this record required exertion in difficult social and physical environments comes through in early park reports, a few highlights of which follow:

The case against Jack Donnelly for killing and transporting game from the Park was considered a very good one, but the prosecution failed because of the reluctance of the people, as represented by an average jury in this instance, to convict anyone for illegal hunting. This general disinclination to punish illegal game killers is recognized by everybody, and the Park seems destined to suffer along with the rest of the territory as a consequence. It is very discouraging for those appointed to protect game and who feel responsible for results. Our only hope for adequate conservation lies in the obtaining of whole-hearted support by the people. Once we get enthusiastic sympathy for our aims—and no thinking, unselfish person denies that they are right—co-operation will follow. The process of swinging the attitude of these people to the point of recognizing the importance and value of conservation of wild life, as practiced by the national parks, promises to be a slow and tedious one, requiring much missionary work.

Superintendent's Monthly Report, February 1924.

May 1927

Ranger Swisher, Pearson and I left for Toklat River in early morning. Going over Thoroughfare (Pass) and down into Toklat, we got in snowslush up to our necks. Dogs could neither walk or swim—we had to pull them across. Got in early, changed clothes, spent the balance of the day cutting logs for cabin.

Chief Ranger Nyberg

November 1927

There was four inches of snow during the month making about ten inches on the level. About two thirds of the month was bitter cold being about thirty-five to forty below towards the last of the month. The winds in the canyons and passes were very penetrating. Streams were overflowing and glaciering up very rapidly. During the coldest weather the dogs had to travel through water which was very hard on the dog's feet during the cold weather. The relief tent at East Fork is all surrounded by overflow ice. The new cabin at Toklat and the dog-houses made this stretch of freighting much less disagreeable than heretofore. If there were several more of these cabins along the trails and along the boundary, patrol work could be carried out much more effectively. It is not fair to the rangers to ask them to patrol in the cold weather and get wet in the overflows and then have to spend the night out in the open under a spruce tree. Especially as they travel alone it is too dangerous to ask any man to do. This month Ranger Pearson was caught in a blizzard in the Copper Mountain basin with the nearest cabin or shelter of any kind 17 miles away. There was no timber in the basin for wood to make a fire and he had to double back 17 miles to the Toklat cabin, arriving late at night. It is important that there should be a cabin at Copper Mountain.

Chief Ranger Nyberg

December 1927

There are twelve trappers at least along the east boundary and seven white trappers and several natives trapping along the northern boundary between Healy and Toklat. There are five trappers between Toklat and Wonder Lake. There are at least four and probably more between Wonder Lake and the West end. Practically all of these trappers have dogs that are fed from caribou and sheep. With a ranger force of three and hardly any cabins along the boundary it is practically impossible to properly patrol this section. With present conditions the rangers are forced to make a hurried trip through, spending the nights beneath spruce trees. Along the 150 miles of boundary which is about two hundred miles the way we would have to travel, there are only four cabins. In cold or stormy weather it is too risky a proposition to send the rangers over this hard stretch with no cabins to stop in. The trappers are well acquainted with these conditions and make use of the knowledge.

Chief Ranger Nyberg

March 1928

Chief Ranger Nyberg and I left Kantishna station at three oclock the morning of the 29th. As the light snow that was falling made the trail unusually good we made the 35 miles to Toklat by nine oclock in the morning; and continued on to Igloo 20 miles farther.

There was game on the trail between Polychrome Pass and East Fork. The teams broke into a fast run, one of the dogs in my team went down and they dragged him a hundred feet before I could stop them. He was unable to rise and I found one of his front legs was broken close to the shoulder. The break was so bad there was no hope of recovery so I took the collar and harness off and shot him. The dogs were continually breaking through the ice on the creek; he was the slowest dog in the team and getting tired he must have stepped through the ice and was unable to pull his leg out soon enough.

Park Ranger Arthur Gardner

Ranger Gardner's evident distress at having to destroy one of his dogs testifies to the rangers ' affection for and dependence on these often unruly and frustrating animals. Dog-team work can be the hardest imaginable for both man and beast. Breaking trail in deep snow with snowshoes, pulling the dogs as they wallow through it, holding the sled on line while floundering across sidehill slopes or sliding in a gale on glare ice, pushing and yelling encouragement as the dogs drag a loaded freight sled up a cut bank—all these standard problems of dog driving leave little time for leisurely sledding through the scenery. Straightening out tangled dogs and lines, deicing sled runners after traversing overflow, and breaking up dog fights that can maim or kill one's only transport in lethal weather and terrain do little to relieve the normal stresses.

Yet, for those who accept these travails to explore the crystalline landscapes of winter the dogs are a constant amazement. No matter how hard the previous day, they greet the morning with eager anticipation—another great day of bone-tiring labor lies ahead. When a good team responds to a good driver the power and energy they display in overcoming the most difficult conditions wrings the heart. For one alone on distant patrol, the dogs are the only companions. They become as family.

Functionally, particularly in the early days (and yet today in specialized tasks) the dogs alone gave access to the park's winter remoteness. Even after the advent of airplanes and snow-cats the dogs proved their worth. Temporarily banished from the park after World War II, they were brought back as dependable complements to the various machines powered by internal combustion engines, which proved fickle in deep cold and bad storm, and dysfunctional in many terrains.

Anyway, the training, driving, and upkeep of dogs has been too integral a part of McKinley-Denali rangering to be valued solely in practical terms. The sled dogs of Denali are both symbol and substance of that tradition that encourages rangers to actually range in the Alaskan wild. Their continuing use for specialized patrol and freighting of supplies, and their unfailing appeal to visitors through scheduled dog-sledding demonstrations, is recognized as one of the park's historic themes, represented structurally by the historic kennels complex and patrol cabins. [45]

In those pioneer years, getting the park going and giving it protection, along with public missionary work, took most of the park staff's time. But emergencies and new duties kept intervening. In July 1924 a major fire surrounded McKinley Station and the park's Riley Creek base camp. Strong winds fanned it along the first mile of the new park road toward the park proper. Summer camps around the station were abandoned. Park families left their quarters to huddle on a Riley Creek gravel bar. Night-and-day work and vigilance, and a change in the weather, ended the danger after 4 days. But the park entrance was a charred wasteland [46]—a contributing reason for Director Albright's veto of Landscape Architect Vint's 1929 recommendation to move the park headquarters back to McKinley Station.

As a result of the Prohibition Amendment and an earlier law prohibiting the manufacture and sale of alcoholic liquors in the Territory of Alaska, park rangers were drafted into the enforcement apparatus to destroy moonshine stills and close down dispensaries. [47] This thankless task exacerbated the park's relations with private landholders around McKinley Station. Both Morino's Roadhouse and Duke Stubb's store had become drinking hangouts for wintering miners, whose squatter cabins had proliferated on the unwithdrawn lands between the park boundary and the Nenana River. Prohibition actions against these two dispensers, and neighboring moonshiners who supplied them, complicated an already strained situation. Particularly grating was Morino, whose strategically located homestead surrounded McKinley Station and the park-entrance corridor. The bitterness sown by these episodes would contribute to Karstens' downfall and create long-term problems when these people and their allies became inholders after the boundary extension of 1932. [48]

|

| Morino's Roadhouse and McKinley post office, 1938. Alaska Railroad Collection, AMHA. |

|

| Morino's Roadhouse from Riley Creek bridge, showing ruins remaining after World War II. Alaska Railroad Collection, AMHA. |

Nor would tourists and special visitors wait until everything was nicely organized. The NPS itself—at first to justify establishment of the park, then to get money for its protection and development—had constantly touted the park's potential for the territory's economy and development. The connection between park tourism and profitable operation of the Alaska Railroad had been exploited continuously since the first public announcement of the park idea in 1915. Little wonder, then, that the sequence of protection first and visitors later telescoped together.

By 1922 the Rand McNally Guide to Alaska and Yukon featured a detailed map of the park showing an established trail from McKinley Station to Wonder Lake and beyond to the very foot of the mountain. [49] At the time of this guide's printing the trail was not even marked.

About the same time a consortium of steamship lines, railroads, and other tourism interests formed an organization called Alaska Vacation Land. Its advertisements in prominent magazines such as The New Yorker and Sunset highlighted McKinley Park on a tour called The Golden Belt Line, which began at the port of Cordova, proceeded to Chitina on the Copper River and Northwestern Railroad, then up the Richardson Highway to Fairbanks, and back to the coast past the park on the Alaska Railroad. [50]

In a circular of July 1924, the Alaska Railroad reminded its agents "that here in Alaska is situated one of America's most wondrous playgrounds." They were exhorted to "boost Mt. McKinley Park whenever and wherever possible." [51] At the time this circular went out the first full-time ARC construction crew of about 90 men had just established their camps and grubbed out the first 4 miles of the road. [52]

A couple of months earlier Karstens had advised Dr. Frank Oastler of New York City that "All transportation, after leaving the railroad, must be by saddle and pack train." He should be prepared for a 2-week outing if he planned a round trip to the foot of the mountain. [53]

Colonel Steese, temporarily heading both the Alaska Railroad and the ARC, warned Assistant Director Cammerer in July 1924 that "we shall do our best to hold people off this year," but unless the NPS could coax more substantial road funds from Congress, the park faced a deluge of disappointed visitors. For every trekker who enjoyed the "very meager and rough camping facilities" and transportation currently available, there would be a crowd at the station to whom "the National Park Service will have to do a lot of explaining." [54]

Karstens, viewing with alarm the visitors' force-fed expectations versus the park's actual state of staffing and development, had earlier written this plaint to the Director:

The establishing of transportation to the park will add to the many other duties of the superintendent and his one ranger. We will do our best, and are eager to cope with any situation that may develop, but is it fair to the Park? [55]

Opening of the railroad from Seward to Fairbanks in 1923 brought a series of VIP tours past the park. Their ceremonial stops at McKinley Station publicized the park's grandeur and beauty. Their frustration at being unable to enter a National Park effectively blockaded by lack of roads and accommodations spurred public clamor. These events helped move Congress to the first significant appropriations for road construction.

On June 7 a Congressional party numbering 65 persons spent an hour and a half at the station. Superintendent Karstens addressed the group, citing the park's urgent need for a road and increased appropriations. [56] Chairman Steese of the Alaska Railroad and ARC wrote to Karstens a few days later to relay "the many pleasant comments we have received concerning your address . . ., I believe we may safely count upon receiving increased consideration at the hands of Congress next winter." [57]

Next, on July 8-9 came the Brooklyn Eagle Party of 70 persons. For several years the Brooklyn Daily Eagle newspaper had sponsored western park tours with the cooperation of the Interior Department and the NPS. Each year they officially dedicated a National Park. This year it would be Mount McKinley.

As originally planned, the 40 or 50 hardier members of the party would be transported over the rough trail to partake of a caribou barbecue at concessioner Dan Kennedy's Savage River camp. But tight train schedules and Kennedy's inability to set up for such a throng at the opening of his first season cancelled that event. Karstens had worked like a dervish to pull this off and, as usual, he would not be defeated. He dragooned everyone in sight to transport and set up the barbecue at McKinley Station. He called in the Biological Survey's caribou man, Olaus Murie, to hunt sheep for barbecue meat. Except for the usual disappointment at being unable to get into the park, the barbecue and dedication came off splendidly. [58]

|

| The Brooklyn Eagle party at the park's dedication ceremony, June 1923. Fanny Quigley Collection, UAF. |

By now Karstens' plaint about extra duties when the railroad brought visitors to the park had the ring of understatement. And it was not over. But cope he did.

Less than a week later, on July 15, President Warren G. Harding's party of 70 persons showed up. After an overnight layover at Broad Pass (the train simply pulled into a siding because the Curry Hotel, the later overnight stop, was under construction), the Presidential Special steamed into McKinley Station. For about 20 minutes the President mingled and shared refreshments with the crowd that greeted him there. Superintendent Karstens accepted the invitation to join the President's party for the Golden Spike driving at the north end of the newly completed Tanana River bridge—the symbolic signal of the railroad's completion. During the train ride to Fairbanks Karstens worked the President's men with stories of the park and a catalogue of its needs. [59]

Shortly after his visit the President authored an encomium to Mount McKinley that concluded with these words: "Somehow Mount McKinley is distinctly typical of Alaska, so mighty, measureless and magnificent, resourceful and remote, with some great purpose yet unrevealed to challenge human genius." [60]

While in San Francisco on his return from Alaska, President Harding died of an embolism. Interior Secretary Work would state in his 1923 Annual Report to new President Calvin Coolidge that "The official visit of the President and his Cabinet has unquestionably done more to direct attention to Alaska than any previous event."

Not all special visits were so pleasant. Famous outdoors writer and film-maker William N. Beach set up a visit to the park in 1922, writing ahead to Karstens and getting his enthusiastic response and offer of help. Beach said he wanted to shoot McKinley's sheep with a camera, but, unstated to Karstens, he wanted to shoot them with a rifle, too. Using his connections he tried to get a special permit for sheep hunting. The Biological Survey helped the territory to manage Alaska game, so Beach approached its chief, Dr. E.W. Nelson. Beach started with a statement to him by Alaska Governor Riggs that he saw no reason why Beach couldn't get a special permit for hunting in the park. Beach then urged Nelson to intervene with the Park Service in his behalf. Nelson refused.

In a letter to Charles Sheldon, Nelson recounted this episode and said that he had written to Karstens to the effect that such special permits for famous people would wreck the park and enrage Alaskans. He went on to say that Karstens' careful enforcement of the park hunting ban would be for nought if any exceptions were allowed. He urged Sheldon to help him head Beach off from further pleas to the Interior Secretary by alerting Mather and Albright. [61]

In the upshot Beach did secretly shoot a sheep near his camp at Igloo Creek. On his return to New York he sent a new Mauser rifle to Karstens as a token of appreciation for courtesies extended. Shortly thereafter Beach attended a society dinner and told the gentlemen next to him that he had killed a sheep in Mount McKinley National Park. The man happened to the assistant field director for the National Park Service.

The Service then moved against Beach, obtaining a signed statement from him acknowledging the illegal kill. When informed of this by the Service, Karstens returned the rifle, which he never had a chance to fire.

Beach had also sent a Mauser to an Alaska Game Warden who had seen the sheep at the Igloo Camp when passing through. The warden kept quiet about the incident, but later admitted to Karstens that perhaps he had seen a sheep head at the camp. Beach was prosecuted before the U.S. District Attorney in Fairbanks in September 1923. He finally pled guilty, after citing a hungry camp as his excuse. He paid a $10 fine and court costs, assessed by a sympathetic U.S. Commissioner. But as Karstens remarked, any conviction for illegal hunting in Alaska was "quite a feat."

The positive results of this unsavory affair were public statements and articles supporting McKinley as a wildlife sanctuary from the new governor, Scott Bone, and Delegate to Congress Dan Sutherland. [62]

Some "just plain folks" came into the park in those early days. One woman who had seen the mountain many times from a distance wrote an account of her 1927 back-pack trip, a few lines of which follow:

But it is only after one has seen Mt. McKinley from the nearer reaches and in such evident cool superiority to its rugged surroundings that he can realize its true fitness as the nucleus for one of the greatest and most attractively wild of all the national parks.

We had drunk some husky tea at noon in rusty tin cans at the desolate Road Commission tent above timber line on Stony Creek and were resting for a few minutes before the ascent into Thoroughfare Pass. Here, deep within the Park (we had traveled forty-one miles, always in the general direction of McKinley, with packs on our backs since we left the comfortable tent camp of the transportation company at Savage River) we felt that the mountain must be very near and knew that it might reveal itself suddenly over some hill like a sheep or a caribou which would appear from time to time along the trail without warning of its proximity.

Quaffing a last can of ice-cold water from the rill near by and piling enough small twisted brush sticks beside the Yukon stove to answer the trail requirement, even whittling some shavings from a gnarled willow stump, we lifted packs on sore shoulders and began to follow the faintly outlined trail which we could see at intervals for several hundred feet up the steep slope. Stopping for a moment in the steepest part of the ascent, we looked back at the landmarks of the trail behind us . . . .

The sky was clear except for a few fluffy clouds floating in the direction of the range. Perhaps we would not see McKinley at all that day. But after a few more labored steps we reached the summit of the pass, and peeking out from the side of the hill on the left was what at first looked like a white cloud, the rugged top of the mountain. The clear outline of the two peaks, the sharpness of ridges on its surface, the unmarred purity of whiteness on perpendicular walls, the wind swept smoothness of depressions all gave the impression of exultant height and aloofness.

This was my first near view of Mount McKinley, the white wonder of the range, the top of the continent. I was destined to see it much nearer in the days that followed and from several different angles, but never was it more impressive than when framed on the left by Copper Mountain and on the right by the hills flanking Thoroughfare Pass. [63]

Completion of the Alaska Railroad keyed a boom in Interior tourism during the 1920s. Joined at Fairbanks by riverboat and auto-road links to the White Pass railroad out of Skagway and the Yukon, and the Copper River railroad out of Cordova, the new Alaska Railroad attracted significant numbers of tourists away from the previously favored coastal towns and cruise ships. Interior hotels and their rustic roadhouse cousins, restaurants, and gift shops featuring Native arts and crafts all benefitted from this shift.

In tune with Alaska's frontier character many accommodations provided only the basics of shelter, warmth, and meals. Tasty wild-meat stews, baked bread, and garden vegetables, served home style, catered to the healthy and hungry traveler. One guidebook warned the finicky: "No allowance is made for delicate or jaded appetites." [64]

The Depression hit Alaska tourism hard. But in the late Thirties the well heeled headed north for fear of Europe's war threats. Then World War II, with Japanese invasion of the Aleutian Islands and the priorities of war mobilization, halted all tourism to the territory for the next several years.

Over much of Alaska the post-World War II revival of tourism followed new routes constructed and perfected during the war. A major development was the opening of direct commercial air travel from the Outside. The Army-built Alaska-Canada (Alcan) Highway allowed direct auto access to Fairbanks from the States. The Glenn Highway connected Anchorage with Fairbanks via the prewar Richardson Highway. Scores of secondary and emergency military airfields—turned over to the territory after the war—opened up remote areas to casual visitors.

But in the yet essentially roadless Denali region, the railroad's prewar-style travel and touring patterns would persist for another three decades. Given the already existing railroad, the military had skipped the Denali region when it built new elements of Alaska's wartime infrastructure. Thus the park continued to be isolated from the independent auto touring that had become commonplace in road-accessible parts of Alaska. [65]

In the early years scientific interest in McKinley Park centered on the large mammals. The park's special status as a game refuge offered scientists the unique opportunity to study the life histories of unhunted animal populations over a significantly large range of the subarctic. [66] Cooperation between the NPS and the U.S. Biological Survey in Alaska began when the latter's assistant biologist, Olaus J. Murie, conducted reconnaissance surveys in and around the park in the years 1920-22. Though his work occurred in the context of a long-term study of the caribou, his early notes and reports yielded meticulous descriptions of flora and fauna of all kinds, couched in the life-zone ecology of the time. Aside from Charles Sheldon's work in 1906-08, which concentrated on the white sheep, Murie's were the first scientific reports relating to the park's biology.

The Biological Survey's chief, Dr. E.W. Nelson, had commissioned Murie to travel all through Alaska on the caribou study. He was particularly concerned with the relationship between imported domestic reindeer—first brought to Alaska in 1892 to supplement Native food supplies—and the larger, sturdier wild caribou. When migrating caribou passed close to domestic herds of reindeer, some of the latter drifted off with the wild animals. Being of the same species, the animals interbred, to the detriment of the caribou. Nelson conceived the idea of improving the reindeer stock by controlled interbreeding with choice caribou bulls. This would not only improve the meat yield of the domestic animals but would also help protect the caribou by transmitting their sturdiness and disease immunities to the reindeer herds, thus making casual encounters less detrimental to caribou. [67]

As a result of Doctor Nelson's correspondence with Director Mather on this subject, Olaus Murie was given permission to capture some of the large bulls at the park for breeding with the reindeer. During the period July 4 to October 23, 1922, Olaus and, from early September, his younger brother Adolph ("Ade") Murie, worked to this end with Karsten's cooperation and a crew of hired hands from Fairbanks.

They made camp on the upper Savage River near its main forks, and built a caribou corral about a mile and a half up the Savage west fork. Murie had studied Indian drive and corral structures in the upper Yukon region and this one followed their design. It had two long wings about 600 yards long that funneled caribou along a well trod trail that came over the pass from Sanctuary River. The wings converged on a gate that opened into a corral about 60 yards in diameter. A small pen inside was used to hobble and dehorn bulls so they could be worked without lethal danger to the wranglers. Captured bulls were taken to the Biological Survey station at Fairbanks to consummate the breeding experiment. [68]

Olaus Murie continued to have intermittent contact with McKinley Park into the early Sixties, with significant influence on the park's biological and wilderness management. But the younger brother, "Ade" Murie, remained a real fixture in the park into the Seventies. His reports on McKinley mammals, birds, and ecological studies number in the scores, with many of them published in popular form. These, plus his periodic evaluation of the wolf-sheep status during the Thirties and Forties, and his many letters and comments on the park's evolving development exerted a force both spiritual and scientific:

* in establishing an early version of ecosystem-management at the park.

*in averting a big-game management bias, which would have included mandatory wolf-control quotas;

*in moderating post-World War II development concepts that would have subjected wilderness and wildlife to undue intrusion; and

*in justifying recent northern boundary expansions to preserve extended wildlife habitat.

In sum, these contributions probably made Ade Murie the single most influential person in shaping the geography and the wildlife-wilderness policies of the modern park.

Ade Murie's alliance with the fate of this park did not happen in a vacuum. In 1926, George M. Wright and Joseph S. Dixon visited McKinley Park to study its "outstanding assemblage of animal life." George Wright was an independent biologist who, at first with his own money, hired or contracted colleagues to form the Service's first wildlife division. He believed that only science-based management could save the National Parks from the devastations of contextual and in-park exploitation and development. Joe Dixon was one of these colleagues, a professor of mammalogy at the University of California. As a first step, they envisioned a series of faunal surveys for each of the great National Parks. They shared the premise that protection of wildlife and their habitats,

far from being the magic touch which healed all wounds, was unconsciously just the first step on a long road winding through years of endeavor toward a goal too far to reach, yet always shining ahead as a magnificent ideal. This objective is to restore and perpetuate the fauna in its pristine state by combating the harmful effects of human influence. . . .The vital significance of wild life to the whole national-park idea emphasizes the necessity for prompt action. [69]

Their accounting for the dynamics and relations of flora, fauna, and geography gave their methodology the cast of modern ecology. [70]

Recognizing the superlative natural laboratory and unique wildlife gathering offered by McKinley Park, Wright and Dixon launched their investigations there, with advice and assistance from the NPS, the Biological Survey, the University of California Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, and the United States National Museum. Their work constituted the first comprehensive, ecologically based survey of the park. The many specific research tasks they proposed continue to enlarge the park's massive scientific bibliography.

Their evaluation of McKinley Park's unique significance in the early years can be read today as a pronouncement on the values of Alaska's expanded park, refuge, and Biosphere Reserve systems developed over the years since their pioneer work:

[Mount McKinley], because of its remote location, favorable climatic conditions, and large size, is the only park today that contains an adequate and abundant breeding stock both of wild game and of large carnivorous animals. Too, the natural association and interrelation of certain typical and vanishing examples of North American mammals, such as grizzly bear, wolverine, timber wolf, caribou, and Alaska mountain sheep, can probably be maintained by reason of the adequate room and the suitable forage conditions. [71]

As these precedent-setting events paced the park's early history, Harry Karstens' superintendency fell on hard times. Despite his continuing accomplishments in the realm of park protection and pioneer development, his volatile personal relations with other officials, park neighbors, the park concessioner, and park employees created an atmosphere of siege. Many episodes were innocent of all but quick temper, even if beyond condoning. Many others were the result of calculated conspiracy and baiting by persons whose interests lay in discrediting the superintendent. But in aggregate, the result was turmoil and publically registered displeasure with the incumbent.

In an attempt to clear the air Director Mather and Assistant Director Cammerer commissioned investigations of Karstens in 1924 and 1925. Cammerer's informant, A.F. Stowe, was a personal acquaintance of the assistant director and a local man who knew the histories of many of Karstens' accusers. At home in the local environment, he quietly observed the individuals and dynamics of the various disputes. In a letter to Cammerer in early 1925 he cited chapter and verse of the origins and motivations of the disputes and parties thereto. He had found attempts to crowd Karstens' legitimate jurisdiction over the park, along with all manner of personal spite, revenge, and envy. He concluded his letter with these words: "I believe today the same as I have always believed that in the present incumbent you fortunately selected the best qualified man living in Alaska for the Superintendency of the Park." [72]

Mather, through the Secretary of the Interior, requested that U.S. Post Office investigators detail every aspect of the charges against Karstens, and solicit opinions as to his competence and stability from such distinguished persons as James Steese, Governor Scott Bone, and newly appointed Governor George Parks. The investigators' report of June 29, 1925, represented 2-1/2 months' work carried out in Seattle, Juneau, Anchorage, Fairbanks, and the park and vicinity. With attached exhibits, the 13-page report, whose substance was an indictment, provides a saddening glimpse into the subsurface labyrinth of Karstens' personal conflicts as superintendent.

The complainants charged Karstens with an arrogant and violent temperament, lack of executive ability, and petty forms of annoyance directed toward any person who differed from him or showed him up. Governors Bone and Parks felt that though Karstens may have been too direct in some of his methods and personal responses, he had probably been unfairly incited by smaller men, whose aims regarding the park crossed Karstens ' duty to protect it. He should, they believed, be transferred to another park where his genuine attributes could be properly channeled and supervised. Colonel Steese came to essentially the same conclusions, but dwelt at length on Karstens' suspicions that everyone was out to get him. Steese further stated that he should be removed immediately so that his presence would not hinder the road project. Other correspondents, as well as the investigators, said about the same: that despite Karstens' many excellent qualities as a pioneer he lacked the poise and balance for public administration. [73]

In the upshot, Mather, Albright, and even old friend Cammerer were forced regretfully but realistically to share that opinion. [74]

During the remaining 3 years of his superintendency Karstens struggled mightily to complete the park's first stage of development and operations. His energies were eroded by many who, aware of the investigation, sensed his vulnerability and capitalized upon his coming demise. Many letters from job applicants found their way to Washington. Karstens' growing belief that his mentors in Washington had lost faith in him did little to relieve his anxiety.