|

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

Conservation in the Department of the Interior |

|

CHAPTER I

IRRIGATION

THE western third of the United States grapples always with one stern fact that does not assail areas farther east. A limiting influence exists in the block of States between Kansas and the Pacific, Canada and Mexico—a region 1,000 miles wide and 2,000 miles long—that clips the wings of its possibilities. Because of it plant life is inclined to languish there, animals appear but fleetingly, and human habitations group themselves only in occasional clusters. Out West there is a shortage of water.

The 1,000 miles immediately to the east, nursed in the arms of the Mississippi, deep spread with alluvial soil, equitably rationed as to rain and sunshine, draw greater wealth from Mother Earth than does any other area in the world. The stretch on the Atlantic, adequately watered but less productive agriculturally, nourishes an industrial multitude.

There are 11,000,000 people in the western belt, 57,000,000 in the middle western belt, and 52,000,000 in the eastern belt. And population and production are low in the westernmost strip only because it is short of water.

Long ago this region settled up to the natural water line; it since has been able to grow only as man, exercising his ingenuity, raised that level. In two-thirds of the Nation water and to spare is always available. Little thought need be taken of it. But in the West it is the one element by which development is measured, and it will remain so through all the years to come. Water is life beyond meridian 100.

|

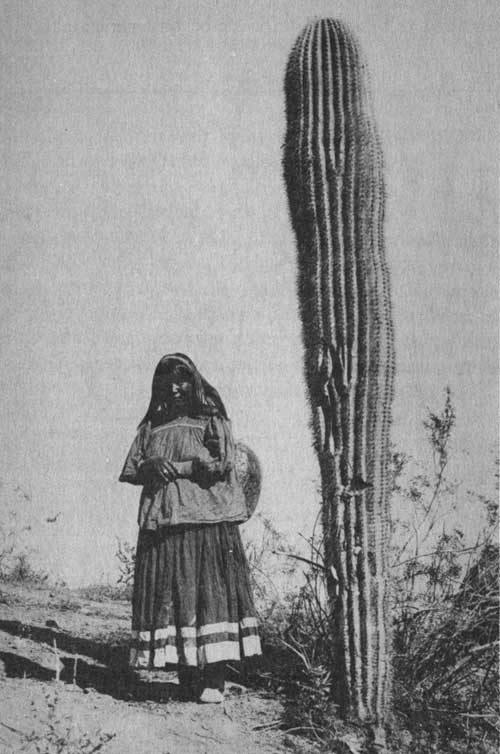

| Before Irrigation Came |

|

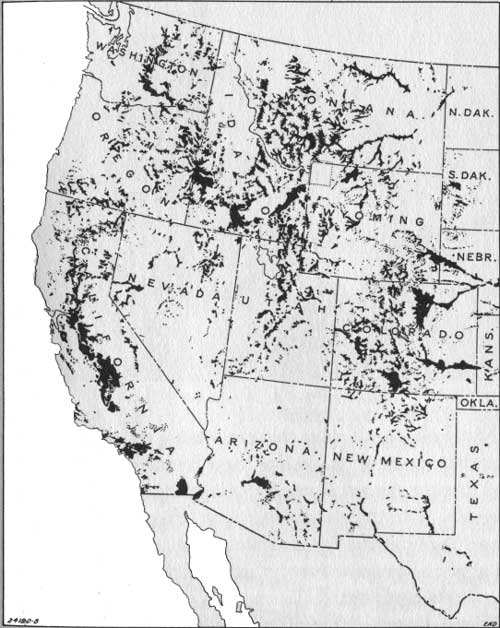

| The Irrigated Lands in the West Are in Black |

Only in occasional spots in this great area is there enough rainfall to produce dependable crops without irrigation. Nature's sprinkling pots bring from 6 to 12 inches of precipitation a year, whereas in Connecticut they deliver 45 inches, in Indiana 40, and in Georgia 48.

|

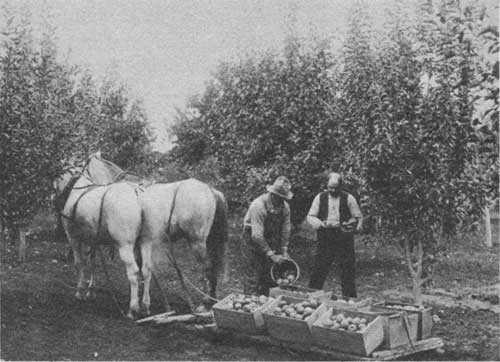

| Choice Apples Replace the Sagebrush of Yesterday |

Ninety-six per cent of the area west of the one hundredth meridian must resign itself to these limited gifts of the lands and forever remain sparsely populated and of low productiveness. But there are exceptions. An area of 30,000,000 acres, as big as the State of New York, is so disposed that by artificial means it can get more of the precious water of the waste lands than falls upon it.

When water makes all the difference between barren desert, where the solitary saguaro stands sentinel, and carloads of strawberries in the early spring, it is obviously a matter of primary importance. Stripped of its lesser essentials, the problem of the West is water. When and where and how much may the water line be raised?

Take the Yakima Valley, in the State of Washington, for instance, as an element in the 4 per cent of western land that may be irrigated. The Yakima River is born of the snows on the east slope of the Cascade Range and flows 175 miles through an open valley where volcanoes of the past have piled ashes 200 feet deep, rich with plant food, to join the mighty Columbia. Little rain fell here, and nothing but sagebrush grew. Man came, diverted the stream flow, developed irrigation. The result was that 100,000 people are living on 600,000 irrigated acres in an area where almost none found homes before.

These homes cluster among the apple orchards where a production yielding $200 per acre per year is not unusual. There is that in the volcanic ash, the sunshine, and dry weather which gives these apples a rosiness of cheek, a firmness of flesh, and a keeping quality that have carried them into the market places of Yokohama, Rio de Janeiro, Cairo, and Danzig on the Baltic. The baled hay and the big baking potatoes of these farms feed nonagricultural activities all about. A city of 22,000 people and a score of thrifty towns exist where but yesterday sagebrush was supreme.

Far to the south, in the burning deserts of Arizona, as a dot in a waste that is unbroken between El Paso and Los Angeles, lies Salt River Valley, Eden of the borderland. Here in the beginning an erratic stream came out of the mountains, sometimes ran a roaring torrent but mostly seeped languidly into thirsty sands. Inspired by the Government's need for hay for Army mules, some rugged frontiersman, back in the seventies, led a ditch from Salt River onto the desert and demonstrated the heavy yields where water is wedded with the desert silt. Ditches became canals, these multiplied themselves. Salt River Valley grew up to the water line which they established and boasted 20,000 people.

But the water supply was irregular, and floods ripped out diversion dams. The Government, 25 years ago, began its first great demonstration of welding mountains together, impounding flood waters, distributing them as needed, stabilizing the behavior of torrents, setting them to spinning turbines, developing communities under this new influence.

|

| Oranges Born of Irrigation |

The enterprise has transformed this cactus-studded desert solitude into an intensively farmed, unbelievably productive, cosmopolitan community that has no counterpart in all the world. Living here are 130,000 people, 50,000 of them in Phoenix, the metropolis of the Colorado River Basin. Farming such lands as these has called forth a skill beyond the appreciation of tillers of eastern acres. Early lettuce goes out in refrigerated trainloads. Single acres have been known to produce 700 boxes of grapefruit. Alfalfa, heritage of the early Spanish fathers, yields six crops a year. Date trees ripen their honeyed fruit in the city parks. Long-staple Egyptian cotton surpasses that picked along the Nile. Production per acre on these irrigated lands of the warm Southwest is likely far to surpass that known in most parts of the world.

The Snake River winds its tenuous way through Idaho and Oregon, carrying much water and inviting man to apply his ingenuity to it. He has responded by raising the water level in the Snake River Valley, and as a result 250,000 people live where before there was nothing of value at all.

Where the Rio Grande runs through New Mexico the early Spaniards developed a ditch here and there and built scattering adobe homes. The Government threw the most massive of its concrete dams across the Rio Grande at Elephant Butte, stored the floods, induced a flow—and brought prosperity to peaceful, semi-Latin communities that fringe the river for 150 miles.

But ahead of all these was Brigham Young, who, traveling with his caravan on the way to Utah, told Jim Bridger, frontier scout, that he intended to plant a farming community beyond the mountains. Bridger pooh-poohed the idea and offered a thousand dollars for the first ear of corn Was grown.

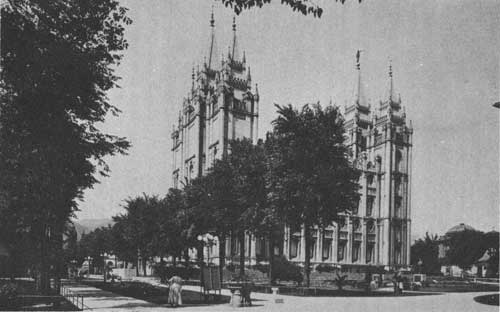

|

| But for Irrigation the Site of the Mormon Tabernacle in Salt Lake City Would Be Barren Desert |

It was July 24, 1847, and the plains were parched when these pioneers, after crossing Immigration Canyon, came out into Salt Lake Valley and unhitched their teams on the brink of a merry little stream afterward known as City Creek. That same afternoon they took their plows off their wagons and broke some of this dry desert land. The very next day the stream was diverted, the plowed land irrigated, and a batch of potatoes planted. This, it seems, was the first bit of irrigation ever undertaken by Anglo-Saxons.

Here in the Great Basin wastes, out of which no stream finds its way, grew the first of the communities born of water under the hands of this race. Various streams coming out of the Wasatch Mountains were diverted and used for irrigation. Later a dam was thrown across the mouth of Utah Lake, 25 miles away. It was converted into a reservoir and tapped by canals which irrigated fertile fields below. Scores of expedients have been used to add to the water supply of the Salt Lake Valley. Each has contributed to the prosperity of this oasis and made additions to the population possible. To-day 200,000 people live in this region, which would have supported but a handful had man not taken thought of water and led it here to serve his purposes.

The classic example of how communities mount step by step as the water line is raised is furnished by the Los Angeles district. Here the Spanish settled 150 years ago and developed a pastoral civilization of a few thousand; the rainfall was not sufficient for stable crop production. Americans who followed increased the water supply by diverting the Los Angeles River into irrigation ditches and by pumping from shallow wells. By 1910 the population had run up to 300,000. It looked as though this community might provide water for drinking, for sprinkling lawns, and for Saturday-night baths for 50,000 or so more people; but the end was in sight.

|

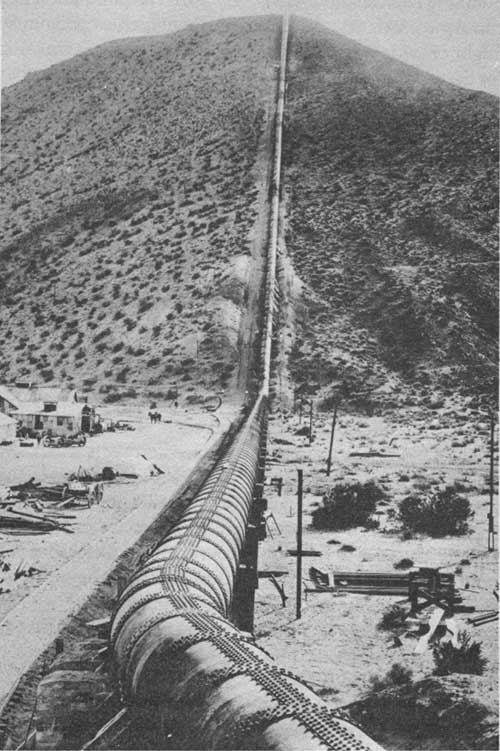

| Los Angeles Adds to Its Water Supply |

It was then that Los Angeles reached out beyond its own watershed, far across the Mohave Desert, 250 miles to the point where the Owens River, fed by the snows of the Sierras, was wasting itself into a brackish lake. Los Angeles diverted this stream and led it through the longest aqueduct in the world into her own front yard, there to multiply the crops of oranges, bungalows, and settlers. Because of this water, brought into the area where it could serve its maximum purpose, 2,000,000 people were added in 20 years to the Los Angeles area. But the population was again approaching the water line. The capacity of the aqueduct could be increased, and probably 500,000 more people could be adequately supplied.

The Los Angeles district thus faced a predicament. In Imperial Valley, not far away, below sea level in a desert as absolute as exists anywhere in the world, nestled another community, born of water, that was likewise in a predicament. It grew of irrigation from the mad Colorado, and now that stream threatened to break from the silt-built ridge upon which it rides and engulf its child. The Government, fortified by its own rich experience and that of private enterprise, accepted the challenge of this great stream to come and shackle it.

Hoover Dam will not end the list of development enterprises in the West. The control of the Columbia River in the Oregon-Washington region is a bigger problem than that presented by the Colorado. The lower Rio Grande offers a dam site in the Big Bend country between Texas and Mexico that is international and might raise the water line all the way to the mouth of the stream. The "Great Valley" of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers, in California, calls loudly for comprehensive control. Sixty or seventy projects, scattered all over the West, have been presented to the Reclamation Service and invite development. Private enterprise is utilizing many more.

|

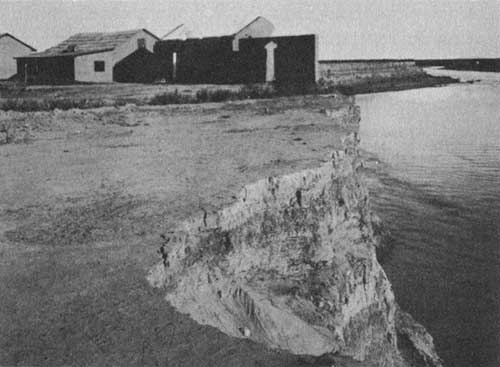

| The Mad Colorado Gnaws at Its Banks |

|

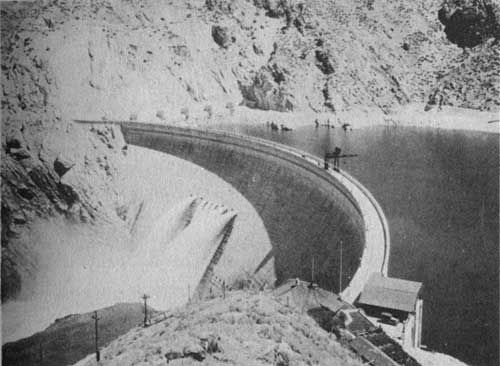

| Arrowrock Dam in Idaho |

There is a strange magic in this conservation of occasional floods that run riot in the land of thirst. It causes concrete giants to grow where nothing else will. Strange substitutes are these giants for the fairies of old who brought about transformations through the waving of wands. Yet the proof of the reality of their miracles is secured first-hand by any doubter who cares to go to see.

There are those who oppose the reclamation of these lands on the ground that, in these United States, there are already too many farms. This may be true of parts of the Nation, but not of the West. One-third of the area of the country is almost without farms. West of Kansas there are but occasional spots, amounting to 4 per cent of the area, that can ever be farmed. To withhold from this vast region the cultivation of those small valleys that lend themselves to irrigation would inflict great deprivation on it and interfere with all manner of western development.

|

| Irrigation Brings Production to the Desert |

Irrigation from the Government standpoint is handled by the Reclamation Service, in the Department of the Interior, which is custodian of a revolving fund amounting on June 30, 1931, to $151,694,000. This fund is used for the development of irrigation projects in the West. The Reclamation Service develops these projects, and they afterwards return the money, which is put into new projects. There are twenty-five of these Federal irrigation projects, irrigating a million and a half acres, divided into 40,000 farms. The crop value on them in 1930 was $65,000,000, and they support a population of nearly half a million people. The fund was created in 1902, when much of the land to be reclaimed was Government land. Lands that have any chance of such reclamation are now largely in private ownership. Their development has become the concern of their owners and of the local community, and new bases of State, private, and Federal cooperation, are being worked out. Taking that development to Washington and turning it over to the Government would furnish an example of paternalism and bureaucracy carried to the extreme.

From the standpoint of the modern-day conservation, the problem of reclamation should be resurveyed and a new set-up established in the light of the changed conditions that have been brought about during the past quarter century. The proper use of this reclamation fund may lie in the building of dams—the establishment of lakes that store water; and the application of that water to the land may be shown to be a local or State matter. If further study confirms this theory, the Federal Government will be able to devote itself and its revolving fund to the task of stopping this precious water, leaving its distribution to local interests.

Those dams which stop the floods of the West and put them in pockets for use when needed are but a part of the scheme which looks to the conservation of water in that part of the Nation that is too dry. The whole western area requires consideration from the standpoint of increasing its orderly yield of water that may be used for irrigation.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

interior-conservation/chap1.htm

Last Updated: 20-Jul-2009