|

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

Conservation in the Department of the Interior |

|

CHAPTER XIII

TERRITORIAL ADMINISTRATION

THE Department of the Interior administers the affairs of the Territories of Hawaii and Alaska, the one laved in tropical seas and the other thrusting Point Barrow into the Arctic Ocean where American soil extends farthest north; the one rocked peacefully in the lap of plenty and requiring little attention and the other in the vast spread of its arms presenting a multitude of problems. Then, recently the Virgin Islands, Caribbean stepchildren of Uncle Sam, have been placed under that department in the hope that careful nursing may lead toward increasing strength and vigor. In each case problems of conservation and the development of natural and human resources have presented themselves. The geographical locations of these three dependencies of the United States in themselves suggest the probable diversities of these tasks.

The happiest of these assignments has been the Hawaiian Islands—4 big and 19 little ones strung out for 1,600 miles and lying tropically but 20 degrees north of the Equator, 2,100 miles from California. These islands have prospered, developed, and lived happily for more than three decades under the Stars and Stripes. They came to the United States of their own free will in 1898, and territorial government was established in 1900. Temperatures which are considered ideal for living out of doors change little through the year. The moisture that is wrung from trade winds blowing from the northeast and climbing the leeward sides of high mountains produces abundant vegetation and furnishes water which often is carried to more arid plains and used for irrigation. Sugarcane and pineapple grow in abundance and excellence and produce satisfactory reward for industry. A third crop, the itinerant tourist, adds to Hawaiian prosperity.

|

| Hawaii in the Mid-Pacific |

Seven thousand miles across a blue expanse of water would be a long trip indeed if it could not be broken. Hawaii, midway between the Orient and the Occident, is an unusually attractive stopping-over place for ships that cross the great Pacific Ocean. Due to this central location and its contacts with Japan, Siberian Russia, China, the Philippines, Australia, New Zealand, the South Sea Islands, Canada, the United States, Mexico, and South America, Hawaii is now becoming of more than commercial importance. It tends to become a cultural center as well as a neutral ground where the nations bordering the Pacific may meet to discuss their common problems. Here the Orient and the Occident meet on a basis of absolute equality. Freedom from superiority complexes and absence of social color lines furnish a field of happy social endeavor. Hawaii's educational, business, and religious foundations are American but stern, and Puritanical ideas here have been softened and mellowed by the native kindliness of the Hawaiian.

|

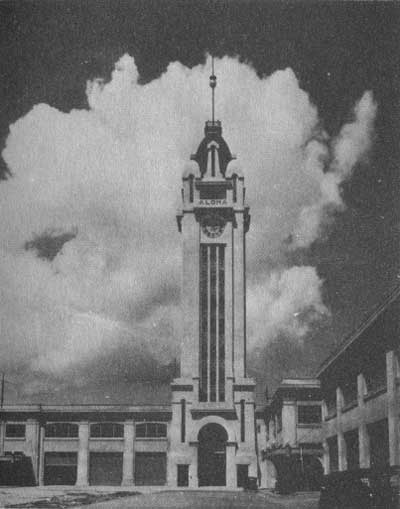

| Aloha Tower in Honolulu Harbor |

Hawaii, at the crossroads of the Pacific, had a charming civilization long before it voluntarily became a part of the United States. Back in the eighteen fifties, before railroads had crossed the Rockies, California families used to send their children to this mid-Pacific kingdom to be educated. Sugar became the chief product of the islands and tariff walls barred it from its logical market, the United States. Annexation leveled those walls, and the result has been decades of prosperity.

|

| The Spirit of Hawaii Speaks Through the Leis Given Departing Visitors |

A governor appointed by the President, a Delegate to Congress elected by the people, sitting in the House of Representatives but without a vote, and a legislature of 15 senators and 30 representatives constitute its government. The governor reports to the Department of the Interior, which is Hawaii's link to the United States Government. He is appointed by the President, but a well-recommended Hawaiian citizen is always chosen. His appointment is the only point at which the Territory of Hawaii falls short of self-government.

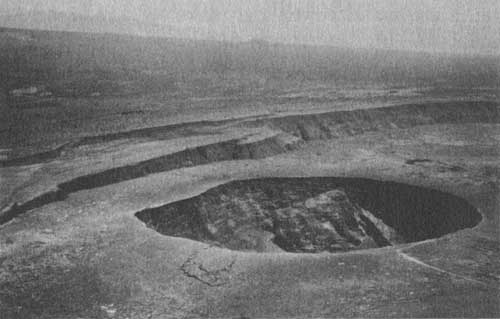

Washington has always held to the theory that it would participate only where necessary or helpful in the administration of affairs in Hawaii. It has maintained an Army base there, a divisional post with some 10,000 troops always in quarters. This is the largest Army post maintained anywhere by this Government. Pearl Harbor has been developed as a naval base. These are merely America's military outriders to the west and have nothing to do with the administration of the islands themselves. Hawaii National Park, with its group of active volcanoes, is a unit in the far-flung scheme administered by the National Park Service of the Department of the Interior. In this same park for decades past, also, has been located another representative of the department, Dr. Thomas Jaggar, world-famous volcanologist, an employee of the Geological Survey. The Department of Agriculture maintains experimental farms in this land of tropical vegetation, which conduct many studies, and staffs which fight insects and rodents that interfere with crop cultivation. The Department of Commerce maintains many stations of the Light House Service. These agencies contribute greatly to the well-being of the Hawaiian Islands, and the benefits accruing from them have come because these islands have seen fit to join up with the United States.

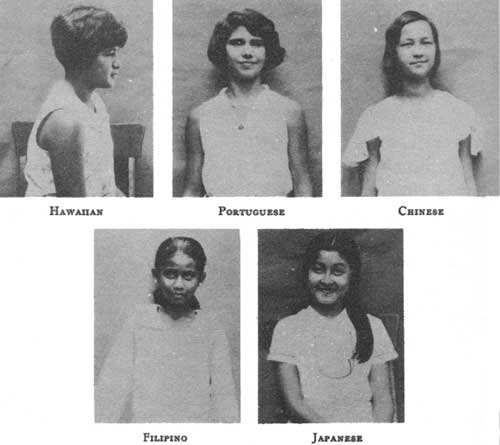

When sugar became the chief product of Hawaii the labor of producing it was done largely by the natives. When that labor supply became inadequate Chinese were introduced, followed by Koreans, Portuguese, and Japanese. So great were the numbers of these orientals that as early as 1907 it was found to be necessary to apply the exclusion laws to them. The planters thereafter fell back on Filipinos, who still were allowed to enter since their home land also was in a way American. Thus it came about that East meets West in Hawaii. A fusion of races making up a population of 370,000 is in progress that challenges all time for its counterpart. There are but some 20,000 full-blood Hawaiians left, with twice as many of part Hawaiian blood. There are 65,000 Caucasians, 25,000 Chinese, 65,000 Filipinos, and 140,000 Japanese. The children of all of these for a generation have mingled in schools such as prevailed in Iowa, back in the States, and emerged English-speaking American citizens, a bit yellow skinned and almond eyed to be sure, but with every right vouchsafed to those born in Virginia and descended from colonial stock.

|

| School-Girl Types in Hawaii |

With the exception of the cities of Honolulu and Hilo, the people of the islands live largely in small towns or villages, and children come to centrally located high schools and grammar schools in auto buses, as the roads of the Territory are well developed.

The schools of Hawaii are well organized from the standpoint of curriculum and teaching methods. Teachers are well trained and are all graduates of a recognized normal school or hold the equivalent of an A. B. degree from the University of Hawaii or some mainland college or university. Teachers come chiefly at the present time from the Territorial Normal School and the University of Hawaii, and they are, of course, representative of the racial groups mentioned. In the main they are progressive, keen, and alert. The many problems of education in the islands are being worked out by practical, scientific methods in keeping with the best ideals of progressive education.

Industrial and vocational education is well taken care of under the Smith-Hughes plan. A department of home economics supplies school luncheons in most of the schools with student help under skillful supervision of teachers.

Despite all this mingling of races, no unpleasant incidents of importance have developed. The children of all these races, growing up side by side, seem to be one in their enthusiasm for and loyalty to the United States. They live happily together, and racial clashes are almost unknown. All participate in government, local and territorial, and the result is comparable with best of successes in Anglo-Saxon communities. Political graft and bad government are almost unknown. Hawaii is a land of good feeling, toleration, happiness, pleasant living. Few communities approach more nearly to the ideal of self government. Washington looks on with approval, lends a hand here and there, almost never exercises even a suggestion of civil authority. A far-away land and a strange and conglomerate people are being conserved in such a way as to produce a prosperous and happy community.

|

| A Hawaiian Crater, Two-Thirds of a Mile Long, from the Air |

The contrast of physical setting and governmental problems could hardly be greater than it is between Hawaii and Alaska. This latter possession is America's last great frontier. Sprawling in such a way that its arms would reach from Norfolk to San Diego, its area is approximately equal to that of all the States east of the Mississippi. It lies halfway on the air route from New York to Tokio. Its three great mountain ranges give it mineral wealth and water power. Its plains are comparable in virgin value and size to the Corn Belt of our Central States.

Great coal veins are exposed on its hillsides, some to a total thickness of 200 feet or more, and there are great hidden stores of gold, copper, and tin. Its forests are perhaps its greatest resource, with spruce, hemlock, birch, and cottonwood in billions of feet. The rainfall varies from 15 to 200 inches, so that there are almost unlimited possibilities in the development of water power. With 26,000 miles of seacoast, the annual harvest of fish alone is now worth $50,000,000. Its glaciers offer unparalleled mountain scenery.

|

| Coal Discovers Itself on the Hillsides of Alaska |

There is the widest variation in its climate from the areas with heavy fog and thick vegetation to dry plateaus like those of North Dakota. The temperature varies from 50 below on the tops of the mountains to 80 above in some of the valleys. The animal life is unique. Fox, seal, and reindeer offer the greatest opportunities.

|

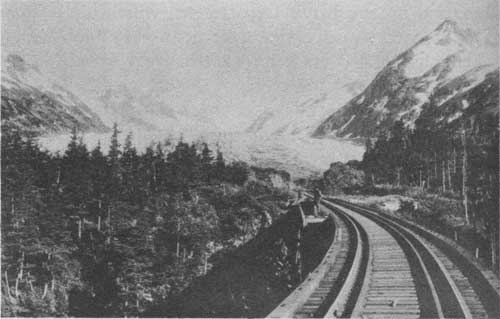

| The Government-Owned Railroad in Alaska |

Most Alaskans are, like all pioneers, full of visions and dreams of the future. As a people we know but little of the Territory. We have yet to appreciate its many values.

Alaska stretches far out into the center of the North Pacific. It brings us near to Russia, China, and Japan. It contributes much to making the United States one of the great nations of the Pacific area. Naturally this vast territory offers many problems to the conservationist.

Alaska, which had up to 1867 belonged to Russia, was purchased in that year by the United States for the sum of $7,200,000 in gold. From 1867 to 1877 Alaska was nominally governed by the War Department.

Thereafter for two years, between 1877 and 1879, the Treasury Department, through a deputy collector of customs, administered the affairs, this service being in turn succeeded by the Navy Department, which had charge of the Territory until civil government was established.

The influx of settlers, after the discovery of gold in the Klondike, marked a new era of development. In 1899 Frank C. Schrader, explorer for the Geological Survey and still in service, came down the Yukon after tramping various areas never previously seen by white man. At the mouth of the river he heard of a gold discovery at Nome, farther up the coast. He went up to make a geological reconnaissance. He found that the gold was being washed out of the sand along the beach. The waves beating there through the centuries had sifted out the light material but the heavy gold had remained. Schrader found, 15 miles inland, a geological beach where the waves had beaten previous to some upheaval of the long ago. It appeared to the geologist that the ocean had beaten longer on the old beach than on that of the present. The sands, therefore, should be more refined, should yield more gold. Schrader made a map of this ancient beach, wrote a report of it, published the report. Nobody paid any attention. A year later a prospector with his pan washed out some of the sand at the inland beach. There was gold in it. It yielded the greater part of the wealth of Nome.

|

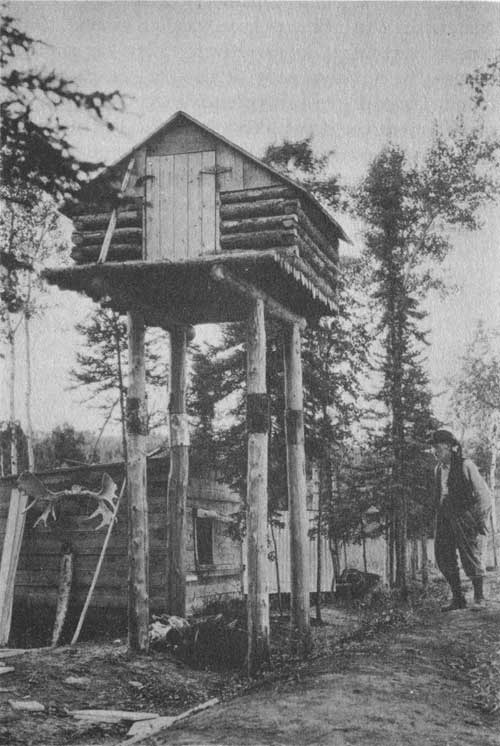

| The Alaskan Pioneer Stores His Food Upstairs and Nails Tin Around Its Supports to Stop the Bears |

Coal has been found at many places in Alaska, and the Matanuska coal field has been yielding around 100,000 tons a year. The Copper River Valley has important deposits of copper already productive. Silver has been found. Huge dredges are procuring increasing quantities of gold from the gravel deposits in the Fairbanks area, while the Alaska-Juneau is one of the great gold mines of the world. Altogether $600,000,000 worth of mineral products have come out of Alaska since the United States bought it for $7,200,000.

|

| McKinley, the Highest Mountain on the Continent |

The Department of the Interior has steadily advanced the development of the Mount McKinley National Park in Alaska, that its unique wealth of animal life and its magnificent scenery may be easily accessible to the American touring public. Mount McKinley is the highest mountain in North America and, in addition, has the distinction of rising higher from its base than any other mountain in the world. Not even the Himalayas rise so far above their base. Of McKinley's total height of 20,300 feet above sea level, the greater portion, or about 17,000 feet, rises above timberline and above the tundra-covered plateau stretching away on its north and west. Two-thirds of the way down from its summit the mountain is blanketed in snow, upon which the summer-long sunshine plays. Great glaciers flow down its southern and eastern slopes.

|

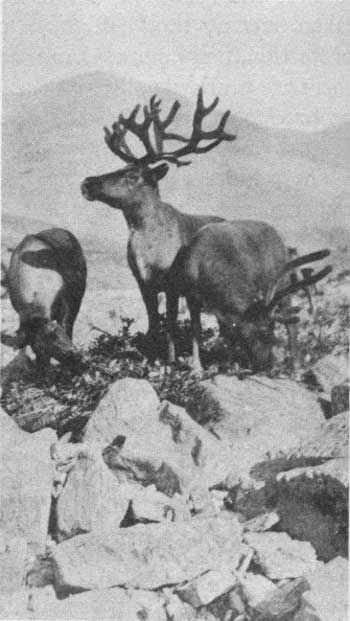

| Alaskan Reindeer |

Especially interesting are the herds of wild animals that roam through the park and that are increasing steadily under the protection afforded them by park authorities. The caribou with its large antlers is picturesque and in great herds roams the vast plateau at the base of Mount McKinley. Mountain sheep also are found here in large numbers, and moose and the great Alaska brown bear often may be encountered. The Alaskan grizzly is also in evidence.

The world has never witnessed two more curious examples of conservation than those of the fur-seal herds of the Pribilof Islands and the reindeer herds of the mainland. Pelagic sealers had reduced the seal herds to a few thou and at the beginning of this century when they were taken over by the Department of Commerce. Through protection their numbers have been increased, until to-day there are nearly a million of them which promise soon to be producing 100,000 sealskins worth $2,000,000 every year.

The reindeer, on the other hand, are handled by the Department of the Interior. There were no reindeer in Alaska until 1,280 of them were brought over from Asia some 40 years ago, intended chiefly as an added food supply for the Eskimo along the Bering Sea and the Arctic Ocean. It was found, however, that an area as big as the State of Texas in the north and west of Alaska could be used for raising reindeer, and the herds have steadily spread. There are now over 600,000 of them, promising the development of a new and important stock-raising industry on a basis new to the world.

Recently a reindeer council was created consisting of the Governor of Alaska, the chief of the Alaska division of the Office of Indian Affairs, the superintendent of reindeer in Alaska, a representative chosen by and from the Eskimo reindeer owners, and a representative of the private interests which own the largest individual herds in Alaska. The reindeer council was instructed to formulate range rules and regulations for the control and further development of the herds and plans for the sale of reindeer meat.

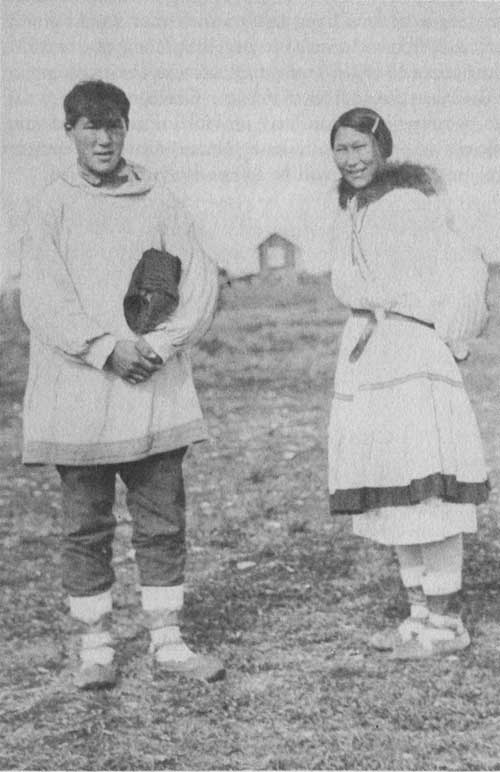

Heaviest of the responsibilities of the Department of the Interior in Alaska has been that for the health and education of the native population. There are 12,000 Eskimo American citizens scattered along Bering Sea and the Arctic. The Aleuts, who are part Eskimo, part Indian, and part Russian, live as great a distance west of San Francisco as San Francisco is west of New York. Far into the interior, where reach the Yukon, the Porcupine, and the Koyuku Rivers, live the Athabascans, most isolated of all human beings on this continent. It is probable that there are groups of Americans at these headwaters who have never been seen by white men and who do not know that a world beyond exists. Down that fringe of Alaska that reaches farthest south, where the climate is warmer, are to be found the Thlingets, the Hydas, and the Metlakatlans, not unlike the Indians of the Northwestern States. In villages that range in population from 30 to 400 these people live, each village largely a unit unto itself.

|

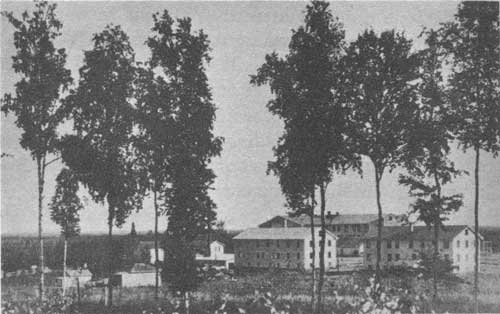

| At Fairbanks, Alaska, Is the Farthest North University in the World |

Already many Eskimos have replaced their igloo homes, which were dirty and insanitary, with houses built largely under the direction of American schoolteachers. They are coming to live as do civilized people. The young Eskimos all speak English and read and write. They have been taught ventilation and personal cleanliness.

Into these communities go American teachers. A man and his wife may be stationed at a point far out on the Aleutians. A zealous young woman may go alone to a native inland village hundreds of miles from the nearest railroad and there remain for years, snowed in for months at a time. A venturesome youth may take a place in the Arctic and find, in the molding of a human community out of a plastic race, a task so fascinating that he lingers long in working out his experiments.

In the Alaskan native community the school is the center of all activity, social, industrial, and civic. The teacher is guide, leader, and much else the community may demand. To be "teacher" in the narrow schoolroom sense is the least of his duties in Alaska. He must often be physician, nurse, postmaster, business manager, wireless operator, and community builder.

|

| A Young Eskimo Couple Dressed for Church on Sunday Morning |

Responsibility for the health and education of these natives, on which $1,200,000 was spent in 1930, rested with the Office of Education until 1931. It was then transferred to the Indian Service as an administrative agency better fitted to carry on this work.

The Government operates and every year loses money on a railroad in Alaska, running from Seward, on the coast, 470 miles to Fairbanks. It was largely in the hope of developing activities along this railroad that would give it sufficient freight to make it pay that Congress, in 1931, appropriated $250,000 for continuation of the investigation of the mineral resources of Alaska. Geological Survey parties, working in Alaska, may provide information as valuable as was that of Schrader at Nome a third of a century ago, and possibly it will be as unwisely disregarded.

|

| School-Teachers in Alaska |

The present policy of the department is to thrust as much of the government of Alaska as possible back to Alaska. Looking to that end, the President has appointed three Alaskan commissioners, resident in the Territory, and has placed much responsibility on them. These commissioners represent departments of the Federal Government in Washington, and each has charge of important elements of administration in Alaska. They are George Parks, Governor of Alaska, representing the Department of the Interior; Dennis Winn, representative of the Department of Commerce, having charge of fishing problems in Alaska; and Charles H. Flory, representing the Department of Agriculture, and having charge of farm, stock, and forestry problems in Alaska. Each of these commissioners has long been a resident of Alaska. Each retains his post as representative of his department and adds to it the duties of commissioner. It will be their business to settle in Alaska many matters that have hitherto come to Washington for determination.

|

| Seward, Gateway City of Alaska |

Strikingly different from the administration of the affairs of Hawaii or Alaska is the task presented by the three principal and two score minor Virgin Islands, on the Atlantic side, outriders to the east of the whole West Indian group, and the most easterly land owned by the United States—1,000 miles toward Gibraltar from Key West, Fla., 40 miles from Porto Rico, 1,400 miles southeast of New York City. These three principal islands are St. Thomas, St. John, and St. Croix. Their dimensions are, respectively, 13 by 2, 9 by 5, and 22 by 6 miles, and they have a combined area of 132 square miles, which is about twice that of the District of Columbia. Only St. Croix is important agriculturally. There are about 22,000 people in the Virgin Islands, a decrease of 5,000 in the last 20 years, of whom but 8 per cent are white. A peculiarity of this population is that the women outnumber the men by 20 per cent. This results from the emigration of laborers to the United States.

The language of the Virgin Islands is English, despite the fact that they were a Danish possession previous to their purchase for $25,000,000 by the United States in 1917. They were bought because they then seemed to have naval strategical value. Their importance as a cable station disappeared with the advent of radio, and the use of oil lessened their importance as a coaling station. Their once important position as a port of call for steamships had disappeared and their population had materially decreased before we took them over. Bay rum is one of the most characteristic products of the islands. Special potable rum made in St. Croix had a limited market which was lost when prohibition became a law. The production of sugar, which for a time was profitable, is now no longer possible on any considerable scale because of the competition of more favored lands elsewhere. Conditions in the islands have grown steadily worse, commencing, however, long before acquisition by the United States. The Danish governors' reports were a continuing account of depression.

From the time of their purchase until 1931, the affairs of the Virgin Islands were administered by the Navy Department. The President, by Executive order, and upon the recommendation of the Bureau of Efficiency, then transferred them to the Department of the Interior. Congress at the same time made quite liberal appropriations for the establishment of civil government. A governor and a technical staff were appointed, proceeded forthwith to the islands, and began to wrestle with the problems.

|

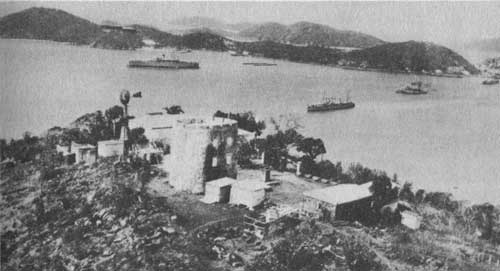

| St. Thomas, Virgin Islands |

Agriculture, obviously, must be the main reliance of this community. Already much has been done toward getting a garden plot into the hands of every family and toward encouraging its members in the cultivation of that plot. In an effort to get the land into individual ownership, plans are under way making it possible to file upon and acquire homesteads. Agricultural instruction is being improved and reforestation is under way. Particular attention is being paid to the development of bay trees, from which bay rum, an important product of the islands, is extracted.

|

| Bluebeard Castle in St. Thomas |

The acquisition of these islands has thrust upon the United States one of those odd tasks that so often fall to its lot. Their possession places upon it the responsibility for doing the best it can under the circumstances. As a task in colonial administration, this one is brand new. Years will be required in showing material results. The task in conservation faced by the department is that of converting this possession into an asset, of leading this group of people into a self-respecting prosperity.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

interior-conservation/chap13.htm

Last Updated: 20-Jul-2009