|

Effigy Mounds

The Perpetual March An Administrative History of Effigy Mounds National Monument |

|

Chapter Five:

LAND ACQUISITION

On August 31, 1949, Acting Director Arthur Demaray of the National Park Service accepted, on behalf of the United States, a gift of 1,000 acres of land from the state of Iowa for the establishment of Effigy Mounds National Monument. [1] The state retained title to another 204.39 acres which it had purchased for national monument purposes pending the receipt of legislative authority to transfer the additional land to the federal government.

The basis for the discrepancy in acreage began in 1937, when Neal Butterfield of the National Park Service's Washing ton office and Howard W. Baker and Edward A. Hummel of the Region II office in Omaha investigated some of the mound groups in northeastern Iowa. Their report recommended the establishment of a national monument of about 1,000 acres in three separate units, with a headquarters area in or near the town of McGregor, Iowa, as a fourth unit. The state already owned some land in the area and the Governor's Executive Council empowered the Iowa Conservation Commission to acquire the rest of the acreage necessary for the Yellow River and Jennings-Liebhardt units of the monument. The United States, in the agencies of the War Department's Corps of Engineers and the Department of Agriculture's U.S. Biological Survey, already owned the Sny Magill property on which the third unit was to be established. By 1944 the state had acquired through purchase, gift, or condemnation, the Yellow River mound area which became the basis for the north unit of the present monument, and the Jennings—Liebhardt mound group which became the basis for the south unit. [2]

Between 1944 and 1946, when the state of Iowa formally offered the property to the Department of the Interior, several changes took place in the plans for the monument. The state acquired several properties for incorporation in monument lands in addition to those initially envisioned; the planners adjusted their concept accordingly. By 1946 the idea of a separate headquarters unit had been all but abandoned, and visions of the monument included a well—developed south unit with the north and Sny Magill unit being held in trust as reserve research areas. [3]

Further, the Park Service decided to put the head quarters unit close to the area of greatest development. Sometime between 1946 and 1948, Service officials began seriously considering the possibility of locating monument headquarters on a terrace near the mouth of the Yellow River on its north side. Even if this piece of land did not become the location of the headquarters complex, its inclusion in the national monument precluded its use for any purpose incompatible with the development of the unit. Further, Service officials reconsidered the wisdom of operating the north (Yellow River) and south (Jennings-Liebhardt) units as discrete entities. As the units were so close together perhaps it would be better to acquire the few acres separating them and have one larger parcel as the core of the monument. In light of these considerations, the Iowa Conservation Commission condemned the sixty—eight acres between the previous southern boundary of the Yellow River unit and the river itself in 1947. [4]

In October 1949, the National Park Service assumed control over these two contiguous areas [5] (including the 204.39 acres the state had yet to transfer officially to the federal government). It was too late to introduce legislation during the session of the General Assembly then meeting, and with Iowa's biennial legislative sessions the request for authority to transfer the additional lands could not be made until the winter of 1950.

The bill passed the Senate on March 15, 1951.

In the interim, V.W. Flickinger, the man with whom the Park Service had worked for three tedious years to ensure the smooth transfer of the land from Iowa to the United States, left his position with the Conservation Commission. [6] Wilbur Rush succeeded Flickinger as chief of the Lands and Waters division of the Iowa Conservation Commission. In mid—August 1950, Rush promised that legislation enabling transfer of the land would be introduced in the next session of the assembly. He also promised to send a copy of the draft legislation to the-Park Service for comments prior to its introduction. In late October, however, Rush's staff was still in the process of drafting the bill. Apparently, the Conservation Commission generally or Rush specifically was not sure what land Iowa still owned. By early December, Rush still had not sent a copy of the bill for National Park Service review. Apparently, the Commission's secretary went on vacation without signing the minutes of the meeting during which the draft bill had been approved; without the secretary's signature approving the minutes of the meeting, Rush explained, they were not official. Finally, Region II Director Howard W. Baker received a draft copy of the bill on December 13, 1950. [7]

The bill was not presented to the General Assembly until late February 1951, possibly because the Conservation Commission was moving its offices during the early part of the month. The two senators who were to steer the matter through the General Assembly anticipated no difficulty in its passage, but Effigy Mounds National Monument Superintendent William J. ("Joe") Kennedy worked with both to ensure steady progress of the bill. As the two legislators had forecast, the bill readily passed both houses of the assembly and was signed by the governor on April 14, 1951, to become effective on the fifth of July. [8]

On July 14, Louis A. Strohman of the Land Acquisition Section of the Iowa Conservation Commission visited Superintendent Kennedy at Effigy Mounds National Monument, informing him of problems concerning a small triangular piece of land that was to have been added to the southwest corner of the south unit. This 0.09—acre parcel was deemed vital for the protection of the Marching Bear group of mounds and the Iowa Conservation Commission had committed considerable resources and effort toward its acquisition. The commission originally sought a much larger piece of land there and, that being refused, tried to buy as little as one acre. Failing that, the commission tried unsuccessfully to persuade the landowner, Leo C. McGill, to agree to a scenic easement on the acre of land. Finally, the Conservation Commission reached an agreement with McGill for the acquisition of a fifty- by 150-foot triangle of land. Unfortunately, the Commission failed to obtain a deed for the plot at that time, and in 1950 McGill sold the farm to Casper and Mary Schaefers without reserving the small parcel promised to the Conservation Commission. The Schaefers knew nothing about the promise and were not bound by it in any case. By the time the Park Service became aware of the problem in 1951, McGill had passed away. Thus the state of Iowa had obtained the authority to transfer to the National Park Service a parcel of land it did not own. [9]

Discussions concerning this land parcel continued for six months. The Schaefers refused to donate the land, but were willing to sell it for twenty-five dollars. The state of Iowa had no funds that could legally be used to buy the tract, and federally appropriated funds could not be used. Still, Acting Director Ronald F. Lee of the National Park Service felt that, if necessary, the Service could probably obtain twenty-five dollars from donated (nonappropriated) funds. The necessity was obviated when the Iowa Conservation Commission found the money and purchased the tract.

However, the Gordian knot of land donation was not yet untied. Sometime between October 1949 and November 1951, someone miscopied the dimensions of this same fraction of an acre, and what the state had purchased was a triangular plot fifty feet long north to south and one hundred feet (not 150) in its east—west dimension. The presidential proclamation and all Park Service expectations were for a parcel with an east-west dimension of 150 feet. According to Wilbur Rush, the fifty- by one-hundred-foot-plot was the largest piece of land the state could obtain without initiating costly and time—consuming condemnation proceedings which, in the end, might not be successful. As matters stood, the state had paid a rate of more than $400 per acre for the plot. Late in November 1951, the Park Service agreed to accept the smaller parcel. [10]

Unfortunately, the delays were still not over. Soon after the United States agreed to accept 0.06 instead of 0.09 acres in the triangle-shaped plot, Rush notified the Region II office that E.C. Sayre, head of the commission's land department, was in the hospital and seriously ill. Sayre did not return to work for four months and in the interim, the commission took no action to transfer the land. Even after Sayre's return to his office on the first of April 1952, imprecise work by the abstractor meant the Park Service did not obtain the abstracts and the state patent until three months later. [11]

In mid-July 1952, Region II Chief of Land and Recreation Planning George F. Ingalls asked Superintendent Kennedy to submit possessory rights reports which were required in order for the government to assume title to the land. Upon receipt, Ingalls returned the forms to Superintendent Kennedy because they listed the date of the inspection as January 10, and the reports needed to show a date after March 6, 1952 (the date the patent was recorded). Kennedy resubmitted the forms on the first of August and they were returned to him again for an inspection date later than April 1, 1952, due to some other technicality. The documents for acquisition of 204.36 acres of and, promised in 1949, were forwarded to Director Conrad Wirth of the National Park Service on August 13, and accepted by Acting Director Hillory Tolson on November 10, 1952. [12]

Early Suggestions for Boundary Changes

While the National Park Service struggled to acquire the property which was to form Effigy Mounds National Monument as envisioned in the Baker, Butterfield, and Hummel report and modified by subsequent Service officials, other changes to the boundary were suggested. Within one month of his arrival, Superintendent Kennedy queried the regional office concerning acquisition of an eight—acre piece of property just northwest of the finger of the north unit which abutted Iowa Highway 13. The owner of the property had died and there was a chance the Park Service could acquire the land. A few months later, H.H. Douglass asked if the federal government was interested in purchasing his eighty—acre tract west of the westernmost boundary of the south unit. The Service chose to reject both offers because the parcels under consideration were outside the monument's authorized boundaries. Changes to the boundaries required congressional action, and the Service was not comfortable asking Congress to change the boundaries so soon after the national monument's establishment. [13]

Toward the end of December 1950, Superintendent Kennedy learned that the Liebhardt estate, abutting the monument on the west and from which large blocks of land for the unit had already been obtained, was to be sold. Correspondence on this matter indicates that Kennedy, working through an attorney friend, had a tentative understanding whereby the estate owners would donate to the Park Service a parcel of land bounded on two sides by the national monument and on the third by Iowa Highway 13. Concerned that the purchaser might develop the land in a manner inconsistent with the monument's goals, and hoping to close the gap in the National Park Service frontage on Highway 13, thus reducing poaching activity and illegal trash dumping, Kennedy suggested that the Park Service acquire the property. The Regional position in matters pertaining to boundary changes of Service areas had not changed, however. Such action would require the support of the Washington office and legislative action; and Regional Director Lawrence Merriam had no plans to seek either at that time. The Regional office advised Kennedy to take no action to acquire the property.

|

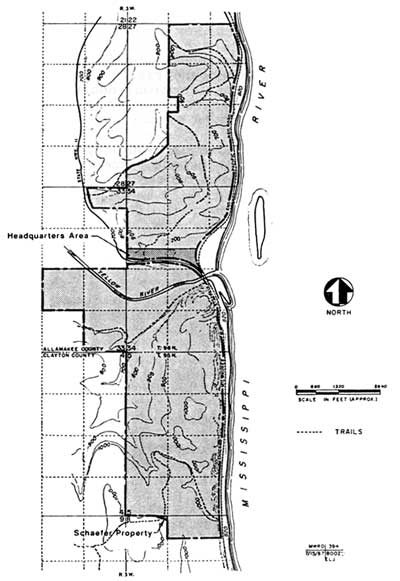

| Figure 10: The original boundary as proclaimed by President Truman included the Yellow River and Jennings-Liebhardt mound groups, the 68-acre headquarters area, and 0.06-acre Schaefer property. |

In 1952 Superintendent Kennedy again recommended the inclusion of the additional Liebhardt land in the monument, having discussed the matter with National Park Service Director Conrad Wirth and Assistant Director Hillory Tolson in the interim. Region II's reaction is summarized in a note initialed by G.F.I. (probably George F. Ingalls) attached to the copy of Kennedy's "Boundary Status Report" recommending this addition:

I told Joe [Kennedy] I thought [Regional Director Howard] Baker might take a dim view of any boundary revision recommendation now to take in the triangular parcel along state highway. This was deliberately not included when monument boundaries were selected. [14]

Founders Pond

Mrs. Addison Parker, Sr., was deeply involved in promoting the authorization of an National Park Service unit in northeastern Iowa, and after 1932 she devoted enormous effort and time toward achieving the national monument's establishment. Louise Parker was a member of the Iowa Conservation Commission during the 1940s while that organization was acquiring the land to be used for the monument, and had remained interested in the unit's development after it was proclaimed. She visited the area in July 1951, at which time, according to park archeologist Wilfred Logan, "We really rolled out what red carpet we had, which wasn't much in those days. . . . We drove her up . . . to see the mounds, see the area, and look over what we were doing, and she was just delighted." [15]

In 1954 Mrs. Parker wrote to Logan to inform him the Des Moines Founders' Garden Club, of which she was a member, would like to do something for Effigy Mounds. Logan and Walter T. ("Pete") Berrett, who succeeded Kennedy as superintendent on June 22, 1953, suggested the club buy a forty-acre plot of land and donate it to the monument. The tract in question was just south of the Yellow River in the south unit and could be purchased from Allamakee County for payment of back taxes and interest, about $200 altogether. One corner of the plot jutted into a backwater lake that was otherwise part of the monument, and that corner was a favorite place for poachers; from the pond they could, with some immunity, shoot the waterfowl on the monument. It was a constant law enforcement problem and source of annoyance. [16]

|

| Figure 11: Louise Parker, longtime friend of Effigy Mounds National Monument, flanked by Associates Director E.T. Scoyen (left) and Regional Director Howard W. Baker, circa 1961. Photographer unknown. Negative #836, Effigy Mounds National Monument. |

Having received a written offer from Mrs. Parker, Superintendent Berrett asked Region II about acquiring this tract of land as a gift from the Des Moines Founders' Garden Club. Berrett informed Regional Director Baker there were two mounds on the property, and that a local farmer also seemed to want it, probably for destructive purposes. Acting Regional Director John S. McLaughlin relayed the request to Washington, commenting:

The suggestion to revise boundaries . . . is not new. Proposals to add these 40 acres to the monument originated in the monument and . . . this office has not looked with enthusiasm on the suggestion. . . . However, Mr. Berrett's advice of August 19 . . . has caused us to revise our thinking. . . .

In view of the existence of two linear mounds on the forty acres in question and the proposal to donate the lands and also with due acknowledgement of Mr. Berrett's administrative problem and the greater ease of fencing since a portion of the boundary would not lie within the pond, we contemplate that our boundary adjustment report for Effigy Mounds will include the recommendation to add this parcel. [17]

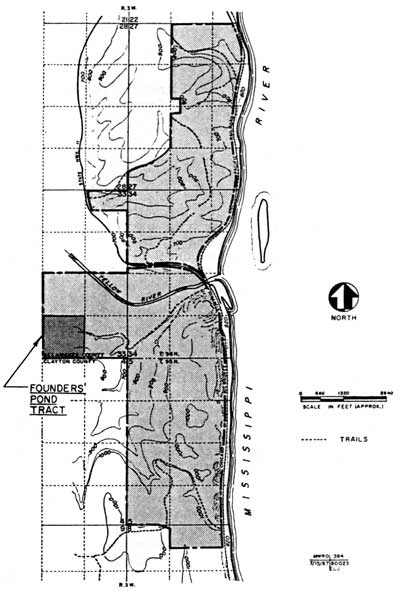

By the following January, the Garden Club had purchased the tract and transferred title directly to the National Park Service. Superintendent Berrett notified both Region II and the Washington office. Baker's November 4 memorandum to Director Conrad Wirth recommended revising the monument boundaries to include both the forty—acre Founders' Garden Club tract and an additional 100.83 acres situated one-third mile north of it. This last block of land included a bird and two linear mounds and encompassed the twenty—two—acre tract north of Highway 13. [18] On September 14, 1955, Acting National Park Service Director Hillory Tolson notified Berrett, Mrs. Parker, and the Region II office the U.S. attorney general had approved the purchase. The National Park Service accepted the property subject to congressional approval of a boundary change. The pond into which the corner of the property rejected was renamed "Founders Pond" in honor of the donors, the members of the Des Moines Founders' Garden Club. [19] Mrs. Parker offered to assist the Park Service in later endeavors, if needed.

The 100-Acre Ferguson Tract

In 1953, a Mr. [?] Pierce of northeastern Iowa offered to donate to the National Park Service the roughly 100 acres north of the tract donated by the garden club, but the Park Service refused the offer, probably because it would have been an isolated tract. Pierce then informed Superintendent Berrett that he would either give nor sell his property to the United States for at least two years; whether because of pique or an agreement Pierce made with a logging company is unclear. In 1954, Berrett learned Pierce had sold the property to the Northeast Tie and Lumber Company, owned by A.B. Ferguson of northeastern Iowa. Berrett contacted Ferguson shortly there after. Northeast Tie and Lumber's office manager told Berrett that Ferguson was willing to sell the acreage in question to the Park Service, and even agreed not to log it for a year pending an agreement, but was not available to discuss a price for it then. Unidentified sources suggested to Berrett that Ferguson probably would accept an offer of fifteen dollars per acre. [20]

With the acquisition of Founder's Pond in 1955, the so—called Ferguson Tract would no longer be an isolated segment as it had been when offered by Pierce in 1953. Indeed, it was now a much—coveted area. In November 1955, Regional Director Howard Baker suggested to National Park Service Director Conrad Wirth (who had known Louise Parker for a number of years) that the Garden Club might buy and donate to the monument the additional 100 acres straddling the Yellow River, or perhaps contribute to the purchase on a matching funds basis. Director Wirth had no objection to approaching Mrs. Parker on the matter, but reminded Baker of the narrow restrictions on the use of appropriated and matching funds for land acquisition. [21] Baker left the decision concerning the advisability of approaching Louise Parker up to Superintendent Berrett.

Berrett decided against it. He was afraid Congress might not approve the boundary change authorizing inclusion of the Ferguson tract as part of the national monument, and felt it would be a great embarrassment to himself, personally, and to the National Park Service if the Founders' Club purchased the land and the Service was not able to accept it. The club had already purchased the pond, which the Service had accepted subject to congressional approval of the needed boundary change. Berrett was not anxious to have the Founders' Club assist in acquiring the Ferguson tract until he was certain the Service was authorized to accept it. [22]

Director Wirth visited Effigy Mounds National Monument in September 1957. Shortly thereafter he solicited the introduction of legislation to adjust the boundaries of the monument to include the Ferguson property. Wirth directed Baker to acquire the tract as soon as possible and not to wait until the boundary adjustment was authorized. Again, Wirth suggested the Des Moines Founders' Garden Club might be willing to secure the tract for the Park Service. Based on Berrett's sources, the National Park Service estimated that $2000 was needed to acquire the land. [23]

|

| Figure 12: Tract donated by the Des Moines Founders' Garden Club, 1955. |

Superintendent Berrett thereupon approached Louise Parker to ask the Garden Club to purchase the land, then donate or sell it to the National Park Service. The club did not meet again until January 1958, but Mrs. Parker was so much interested in the addition that she proposed approaching the Iowa Conservation Commission immediately about buying the property for donation to the Park Service. If the commission could not or would not make the purchase, the Des Moines Founders' Garden Club would take up the proposal at their January meeting. Mrs. Parker apparently arranged for Pete Berrett to meet with A.B. Ferguson to discuss the acquisition of the tract, and later she offered to provide the money necessary to bind an option, if the Park Service could obtain one. However, during the December 1957 meeting with Ferguson, Berrett found that he wanted $48 per acre for his land, considerably more than anticipated. Ferguson acknowledged that his tract was not viable for logging activity, but told Berrett there were two sportsmen's clubs interested in opening the property for duck hunting. From the tone of his subsequent communications, Berrett was skeptical of Ferguson's purported prospects, and efforts to acquire the tract were deferred until Congress had approved the changes in the monument boundaries. [24]

|

| Figure 13: Left to right: Regional Director Howard W. Baker, Archeologist Robert T. Bray, Superintendent Walter T. ("Pete") Barrett, Ranger David Thompson, and Director Conrad L. Wirth at Effigy Mounds National Monument, 1957. Negative #11, Effigy Mounds National Monument. |

The legislative proposal to adjust the boundaries of Effigy Mounds National Monument, which called for the inclusion of the Sny Magill mounds in addition to the forty-acre gift from the Des Moines Founders' Garden Club and the nearly one—hundred—acre Ferguson tract, was submitted to the 86th Congress in the fall of 1958, resubmitted the following year, and again in 1960. By mid-1961 the boundary changes had been approved and Congress had appropriated two thousand dollars to purchase the as—yet unacquired one hundred acres. [25]

Upon learning that funds were available, Superintendent Daniel J. ("Jim") Tobin, Jr., [26] who replaced Berrett as superintendent in November 1958, reopened negotiations with Ferguson for the purchase of the one—hundred—acre tract. Ferguson's reply, mailed from California, stated he was thinking "very seriously of developing [the acres in question] for cottages and also for hunting and fishing resort possibilities." [27]

The status of the property remained unchanged for the next decade. The whole eleven hundred acres in the Yellow River valley came to be known as the Ferguson tract, after its owner, and later his widow and heirs. Ferguson moved to near Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, and each year the incumbent superintendent or another National Park Service representative made a pilgrimage to his home to repeat the Service's offer to buy part of his land. Sometimes the National Park Service sought all of the nearly one hundred acres authorized; some times the Service requested only the smaller five- to fifteen-acre tract around the two mounds which could be purchased with the two thousand dollars available. Ferguson said he would allow an independent appraisal, but only at his convenience, and the time was never convenient. He said he would sell a small portion of the acreage authorized after he had looked the land over again, but unfortunately his health failed before he was able to follow through with the offer. Eventually, Ferguson offered to sell the one—hundred—acre tract for ten thousand dollars, or his entire eleven-hundred-acre holding for fifty thousand dollars. [28] At one time he offered to donate the one—hundred—acre parcel to the Park Service, provided the Service would certify the value of the gift at fifty thousand dollars for the purpose of a tax credit. Each year Ferguson told his Park Service visitors that a sportsmen's club was negotiating for the property, or that he was on the verge of developing it himself with motels and concession facilities along the highway across from the monument. Frequently, Ferguson threatened to build a hunting lodge atop the bird effigy, after leveling the mound for the artifacts it contained.

Apparently Ferguson knew the National Park Service wanted the property as part of the monument, but also that the Service did not want commercial development so close to the park, particularly at the cost of an effigy mound. [29] The Service representatives were skeptical of Ferguson's purported alternatives, but each nevertheless kept the Regional Director informed of Ferguson's repeated claims, and hoped the Service would obtain enough money to purchase the one hundred acres authorized in 1961. [30]

Nothing came of the repeated meetings with Ferguson just as nothing came of the repeated pleas to Midwest Region [31] for more money to acquire the whole eleven hundred—acre tract. The Washington office, "in view of the recent enactment of Public Law 87-44 [the Act of May 27, 1961, authorizing the enlarged boundaries and appropriating two thousand dollars] was reluctant to seek "amendatory legislation" to request more money. The Assistant Director for Resource Planning Ben H. Thompson suggested that the superintendent obtain assistance from the Founders' Garden Club to purchase the land. [32]

Finally, in January 1965, the Washington office agreed "sufficient time had elapsed since the Act of May 27, 1961, . . . to make it politically expedient to request amending legislation," but there is no indication that such legislation was introduced at that time. [33]

Without adequate funds to pay for the one-hundred—acre tract, the Park Service could not start condemnatory proceedings, and it was reluctant to condemn the smaller and more affordable ten or fifteen acres unless it became essential to do so to save one or more of the mounds from destruction. [34] Not until 1971 did a bill to provide the additional funds come to the floor of the Congress for a vote. In early 1972 an additional $12,000 was approved for the purchase of the land that had been authorized in 1961. [35]

In the interim, A.B. Ferguson had died, so negotiations to acquire the one hundred acres were conducted with the lawyers assigned to administer his estate. Mrs. Ferguson insisted upon selling the whole eleven—hundred—acre tract as a unit, but the Park Service was prohibited by law from purchasing lands outside the monument boundary, and the 1961 boundary change authorized the addition of only one hundred acres of the Ferguson land. Midwest Regional Chief of Lands John W. Wright, Jr., told the Fergusons' attorney to advise the Service if Mrs. Ferguson changed her position on selling the desired one hundred acres. [36] A change of lawyers representing the estate caused a brief delay, but within a fort night the new attorneys counter—offered to sell the one-hundred-acre parcel for one hundred dollars per acre, a price twenty dollars per acre higher that what the Park Service was offering. [37]

Then another fly dropped into the ointment. On July 15, 1974, Ranger William Reinhardt, a seasonal employee of Effigy Mounds National Monument, guided a party to two large bear effigies on the Ferguson property, [38] well outside the acreage the Park Service was in the process of acquiring. Negotiations stopped while Acting Regional Director Robert Giles advised Superintendent Thomas Munson, who assumed the superintendency of Effigy Mounds National Monument in January 1971, that the entire area adjacent to the national monument should be studied to determine what changes in the boundaries were needed. There were no funds to accomplish the historic resource study Giles recommended, however, so negotiations to purchase the one hundred acres resumed shortly thereafter. The one—hundred—acre tract was finally included in the nation al monument in late August 1975. [39]

The Teaser Exchange

The last adjustment to the boundaries of the main body of the monument took place between mid-1981 and July 16, 1984, by an exchange of property. Because the original and most subsequent cessions of land had pretty much followed section lines or subdivisions thereof, the national monument owned a small piece of land northwest of County Road 561, and the purchasers of the portion of the Ferguson tract outside the national monument had a piece of a similar size southeast of the road. In 1981 Roberta Teaser, who owned the parcel southeast of Road 561, approached Superintendent Thomas Munson to discuss trading one piece for the other. The Teasers wanted their land to be a contiguous unit on one side of the road for ease in fencing, logging operations, and the like. Those same reasons appealed to Munson, who also recognized that the elimination of the small inholding would close off one remaining base from which poachers could invade monument lands.

|

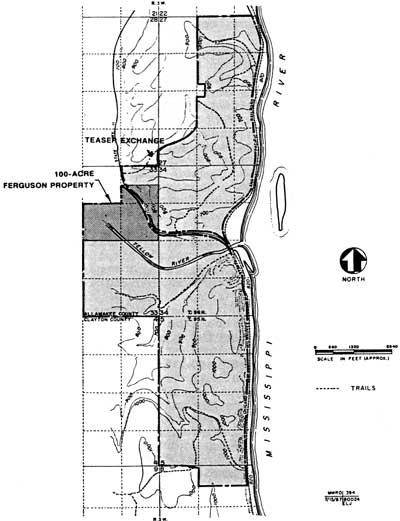

| Figure 14: The 100-acre Ferguson property, which became part of Effigy Mounds National Monument in 1975, and the Teaser exchange, 1984. This is the current boundary of the north and south units of the national monument. |

With the blessings of the Regional Director, Munson sought and received approval from the state of Iowa [40] to accomplish the trade. Meanwhile, Mrs. Teaser induced U.S. Senator Charles Grassley to introduce the needed legislation. Although there was no opposition to the measure, it did not get out of committee in 1982. However, in 1983 Congress passed the legislation, and on July 16, 1984, the National Park Service traded 2.06 acres of land in exchange for an 8.82-acre tract south of County Road 561. [41]

Sny Magill [42]

There seems never to have been any question about the desirability of including the Sny Magill mound group in the national monument. The Baker, Butterfield, and Hummel report of October 7, 1937, the basic document relating to the reconnaissance of northeastern Iowa to advocate areas for inclusion in a Park Service unit there, contains the following recommendation:

The Sny-Magill group and the surrounding area is at present under the protection of the Biological Survey and consequently is not recommended by then Iowa Conservation Commission for inclusion in the Effigy Mounds National Monument. Because this is one of the largest effigy mound groups in this region, and probably one of the largest extant in the United States, we believe every effort should be made to have this group included within the proposed monument. This area lies about six miles south of McGregor, on a terrace along a secondary channel of the Mississippi.

. . . To make a complete unit for administration it is recommended that we include all the Biological Survey area plus the area south to Magill Creek which we are recommending for our south boundary. [43]

In spite of agreement that the Sny Magill group belonged in the national monument, the decision to postpone the acquisition of Sny Magill came early. The addition of the area was postponed for a variety of reasons, as discussed in the previous chapter. Most important, the Service believed the mounds were being adequately protected by other federal agencies. Further, the War Department's Corps of Engineers had taken jurisdiction over some parts of the mound group in connection with its Mississippi River flood control and canalization projects. Upon inquiry, Region II Director Lawrence Merriam was informed that the lands in question were in the process of being transferred to the Department of the Interior for fish and wildlife refuge purposes, but that the Corps would retain certain rights after the transfer. These included the right to flood the area, as needed, to ensure safe navigation, and the right to remove and dispose of "all wood, timber, and other natural or artificial projections or obstructions" in or near the pool behind Lock and Dam No. 10. [44]

Still, the mound group was so outstanding that Regional Director Merriam recommended that the inclusion of Sny Magill in the national monument be discussed in the proclamation designating Effigy Mounds. Unfortunately, National Park Service Director Arno Cammerer feared the rights reserved by the War Department would be detrimental to the monument as a whole. Cammerer suggested a cooperative agreement with the U.S. Biological Survey "whereby that service would assure protection of archeological remains and grant this Service the privilege of excavating sites and approving the requests of archeologists" who wanted to study the mounds or their contents. Cammerer cited his intent to include the Sny Magill group in the monument if, at any time, the Corps released their reservations on the area. In the meantime, the Regional Director of the Biological Survey did not feel there would be any difficulty in working out a cooperative agreement to protect the archeological remains. [45]

In March 1947, the Corps of Engineers notified Region II that further investigation by the Corps' representatives had revealed that the Sny Magill mounds were all at elevations greater than 614 feet, and were not affected by the pool behind Lock and Dam No. 10. Regional Director Merriam's response to this news was immediate and clear:

Our studies for this proposed monument convinced us that the mounds in the Sny-Magill area were of sufficient interest to make it desirable to have them thus set apart. This office never abandoned hope that this unit could ultimately be included in the proposed monument. Our recommendation is that the Sny-Magill Mounds area be included in the proclamation as a part of the national monument. [46]

At a meeting of National Park Service, Fish and Wildlife Service, and Army Corps of Engineers representatives on April 22-23, 1947, Corps of Engineers District Engineer Col. W.K. Wilson reiterated the Corps' belief that dam operations would not affect the Sny Magill mounds. Although everything appeared to favor National Park Service acquisition of the mounds, Fish and Wildlife Service Regional Director [?] Janzen asked that the Park Service delay requesting a transfer of land from the Corps of Engineers and/or the Fish and Wildlife Service for the time being, because "negotiations for transfer of a considerable amount of War Department lands to the Fish and Wildlife Service in this general area have been in process for some time." Janzen was concerned lest a request from the National Park Service to the Corps of Engineers delay the consummation of the transfer from the War Department to the Fish and Wildlife Service. [47]

|

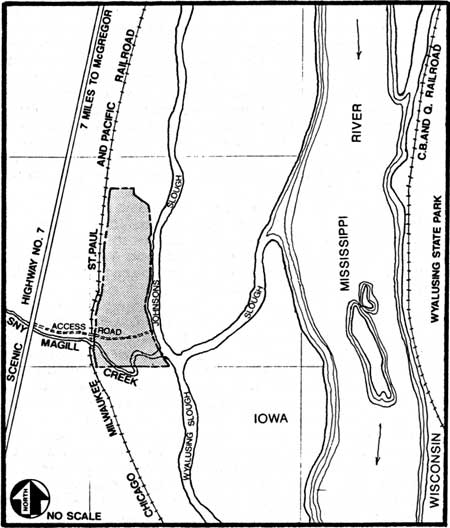

| Figure 15: The Sny Magill Unit, added to Effigy Mounds National Monument in 1962. |

Again, the transfer was postponed, but there was considerable discussion between the National Park Service's Washington and Region II offices, and between both of them and the appropriate Fish and Wildlife Service offices throughout the rest of 1947 to determine what the boundaries should be when the shift in ownership occurred, and to unravel who owned what land. Then, on February 16, 1948, Director Newton B. Drury notified Region II of a major problem:

The Upper Mississippi River Wildlife and Fish Refuge, which includes the southern half of the Sny-Magill unit, was established by Act of Congress and there appears no way by which a direct transfer of the lands could be made to this Service. The northern half of the unit, under the jurisdiction of the Department of the Army [the War Department, as renamed under the reorganization of 1947], as acquired from the state of Iowa through condemnation proceedings. Accordingly, an act of Congress would be necessary to obtain either or both of these tracts. Conceivably, the Sny-Magill area might be included in the monument by proclamation . . . [but] this plan would likely lead to complications. . . . Unless you have compelling reasons to the contrary, we will initiate a proclamation [establishing the north and south units as Effigy Mounds National Monument] as soon as title to the main unit has been accepted. [48]

As indicated in the closing paragraph above, the director's desire to lose no more time in obtaining President Truman's proclamation of Effigy Mounds National Monument was a major reason for his reluctance to pursue the addition of Sny Magill in 1948. Congress had already voted an appropriation to run the unit, and there was some apprehension that if it were not used, Congress might be reluctant to approve funds for the following year. Still, as Regional Director Merriam noted in a memorandum to the Director:

The scientific reasons for including the Sny-Magill group in the original proposal are still valid. It is our thought, and we believe you concur, that this group should be included in the monument eventually. We assume that your office will continue conversations with the Department of the Army and the Fish and Wildlife Service so that the necessary legislation can be prepared at the appropriate time. [49]

After President Truman proclaimed Effigy Mounds National Monument in October 1949, the National Park Service was not willing to ask Congress for a revision of the unit's boundaries for some years, lest it appear it did not know what it was doing when the original boundaries were set. Therefore, the National Park Service did not address the subject for some time. Several months later The next documentary reference to Sny Magill is in a memorandum from Superintendent Joe Kennedy at the monument, reporting to the Region II Director that some Fish and Wildlife Service [50] personnel believed the Sny Magill mound area was already part of the national monument. [51] Perhaps because of this mistaken belief, or perhaps because Fish and Wildlife Service was sure the Park Service would soon take possession of the mound group, National Park Service never had any difficulty in getting permission from other agencies for archeological work at Sny Magill. Regional Archeologist Paul Beaubien did both an archeological survey and some excavating of a few of the mounds there during the summer of 1952. In his April 1953, memorandum transmitting Beaubien's technical report, Acting Regional Director John S. McLaughlin recommended changing the monument boundaries to include the Sny Magill mounds. [52] All the early superintendents advocated including the Sny Magill mounds in the monument, but from 1954 through 1957 Effigy Mounds was operated on a maintenance-only basis. In 1958, however, legislation was submitted to Congress to add the Sny Magill group, as well as some other lands, to the monument. This authorization for changing the boundaries was not approved until mid-1961. In July 1962, the Bureau of Sports Fisheries and Wildlife transferred 69.33 acres to the National Park Service and the Department of the Army transferred 69.11 acres. With this important addition the national monument protected 1467.50 acres. [53]

Significant Areas Not Included in Effigy Mounds National Monument

The FTD Site

There are several areas close to, but not on, monument land that have long been of interest to Effigy Mounds personnel as well as Park Service and other archeologists, historians, and preservationists. Probably the most important of these is site 13 AM 210 (the so—called "FTD site") which lies between the present monument headquarters complex and the Mississippi River to the east. It is situated on land owned by the state of Iowa, and the Corps of Engineers has jurisdiction over an ill—defined "normal high water mark."

The FTD site may be one of the most important archeological sites in northeastern Iowa, as it seems to have been the location of camps or villages from the French fur—traders of the historical era back through the Oneota and Woodland and perhaps to the Archaic period, with a possibility that even earlier levels might exist. Only two village sites relating to the Effigy Mound Builders' culture are known to exist in the entire four—state area where effigy-shaped tumuli are located. Because of the scarcity of information concerning the Effigy Mound Builders, and because the FTD site contains several stratified components, its preservation is essential. [54]

The Nazekaw terrace on which the site is located seems to have extended considerably further into the river before ponding and canalization for navigation purposes artificially raised the water level. In 1980, unusually low river levels exposed portions of the site not seen before. [55] The state historic preservation office authorized Dr. Clark Mallam of Luther College to collect surface artifacts exposed by the low—water conditions. [56] The following year, aware that the wash from passing barges was causing serious erosion damage, the Corps of Engineers constructed a rock dike to keep the wash from barge traffic from further damaging the site. [57]

The FTD site extends for more than fifteen hundred feet along the Mississippi River, and for about two thousand along the foot of the bluff adjacent to the national monument. [58] It is possible that, at one time, the whole triangle bordered by the river, Highway 76, and the foot of the bluffs was archeologically rich, but farming and railroad and road construction have destroyed large sections of this terrace. Because the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad, in building their elevated roadbed cross the terrace, used material taken from borrow pits on each side of the railroad embankment, the pits are now ponds. Artifacts ranging from brick to primitive stone tools, found when the elevated roadbed was built, have been lost, scattered, or destroyed. In 1892 Theodore H. Lewis of the Lewis-Hill survey recorded two bear effigies, "one ruined tailless animal, twelve embankments, one club—shaped embankment and thirty—seven round mounds" on the terrace west of the present railroad line, near where monument headquarters is today. In 1926 Ellison Orr recorded only two bears and seven conicals in the same area. At the present time three conicals and possibly two linear mounds exist there. [59]

The National Park Service considered requesting a change in the monument's boundaries to include the FTD site as early as 1964, but Regional Director Lemuel ("Lon") Garrison felt it was too soon to ask Congress for another boundary adjustment. In March 1967, Superintendent Stuart H. ("Mike") Maule asked the Regional Director to pursue a boundary change to include the FTD site, the Ferguson tract outside the monument, and some mounds on the neighboring Bruckner property. [60] There is no record of the Region's response; no action was taken. Superintendent Milton Thompson requested the Regional Director seek authorization to add the Ferguson parcel only in 1970, [61] indicating that hope for adding the FTD site had dwindled.

The Ferguson Tract

The two bear effigies of the Reinhardt mound group were mentioned above. Named for long—time Effigy Mounds seasonal employee William H. ("Bill") Reinhardt, this group comprises two known bear effigies and a possibility of five to six more bear—shaped tumuli. [62] The mounds are located on top of a steep—sided and narrow ridge in the portion of the Ferguson tract outside the national monument, just over two air miles west—northwest of monument headquarters, with the unexplored five or six effigies along the crest of the same ridge about a half—mile east of the first two. The two explored mounds are unusual in that they are lying on their left sides, whereas almost all the other animal effigies are portrayed as lying on their right sides. Exploration and excavation might reveal other and perhaps even more significant features to distinguish these mounds from others. Clearly, the mounds should be preserved, and since their discovery in 1974 there have been repeated, but so far unsuccessful, attempts to bring the area under the protection of the National Park Service or the Iowa Conservation Commission.

The portion of the Ferguson tract outside the national monument is of general interest to Effigy Mounds personnel because of several rock shelters and other habitation sites; whether these sites are historic or prehistoric is unknown at this time. The area is also of interest because of the flora and fauna it contains. Most cultural and natural resources managers agree that destruction of the forest on the Ferguson tract would significantly affect the biota of the national monument. The monument is a potential nesting site for the bald eagle, a federally listed endangered species, and for the red—shouldered hawk, listed as endangered in the state of Iowa. These birds require large expanses of natural wood lands; elimination of the Ferguson tract forest would almost certainly reduce the attractiveness of the area as a nesting site. Similarly, logging the tract would impair the habitat of the river otter, a threatened species in the state of Iowa. The impact on smaller species of fauna and flora is harder to assess, but an effect on such species as the state—threatened jeweled shooting star (known to exist in the Ferguson tract) is very likely. [63]

Historical Archeological Sites

Other areas of concern for Effigy Mounds personnel are the Red House Landing site and, to a lesser extent, the Johnson Landing site, both on the Mississippi River at or near the northern end of the north unit. Red House Landing, was the site of one of the very early white settlements in Iowa, a steamboat landing and refueling stop, and one of the major locations for clamming for the pearl-button industry around the turn of the century. In addition to shell mounds of historic and, apparently, prehistoric vintage, there are historic Indian, fur trader, and settler habitation sites as well as indications of prehistoric Native American rock shelter and other camp sites. [64]

One source claims the town of Nazekaw was platted but never developed. Others claim there was settlement in the town; at one time during the late nineteenth century a large steam gristmill is alleged to have been located there, and the 1900 census showed nearly 300 people in Nazekaw, although all 300 might not have been living within the platted boundaries of the town. In addition to whatever remains of the town and its buildings, there are scattered indications of Native American habitation sites in the same general area, including some reported to contain copper artifacts. Parts of this townsite are included in monument lands in the vicinity of the visitor center, while other parts are on the railroad or highway rights—of—way, and part is on Iowa common lands along the Mississippi River. Parts of the Nazekaw townsite have been destroyed by railroad and highway construction. [65]

The "Highway 13 rock shelter" probably should have been renamed the Highway 76 rock shelter when the state road was renumbered. It is situated on the highway right-of-way just off monument land, at the approximate midpoint of the south unit's eastern boundary. It was partly excavated once, then severely damaged when the highway was widened, and later "lost" for several years. The rock shelter has been partially excavated and still contains artifacts of considerable interest. [66]

The Jefferson Davis sawmill site is on the Yellow River, some three miles upstream from the river's mouth. The re mains, which are few, were discovered by Ellison Orr in the 1940s, and at present the ruins of both the mill foundation and the log dam are covered by the artificially high water from the pool behind Lock and Dam No. 10. There is very little left of the buildings that once were on the site. [67]

Most of these sites are outside the boundaries of Effigy Mounds National Monument, and at the present time there seems little likelihood of further boundary adjustments. Some of the areas, such as the FTD and the Red House Landing sites, have a direct relationship to the monument's mission and are badly in need of some form of protection. Some parts of these two areas, as well as portions of others, are located on Iowa's common lands, which can be purchased by anyone at any time. The other sites discussed above relate less directly to the primary significance of Effigy Mounds National Monument, but they, too, are valuable and should be considered for protection.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents >>> | Next >>> |

efmo/adhi/chap5.htm

Last Updated: 08-Oct-2003