|

EL MORRO

Guidebook 1941 |

|

El Morro National Monument

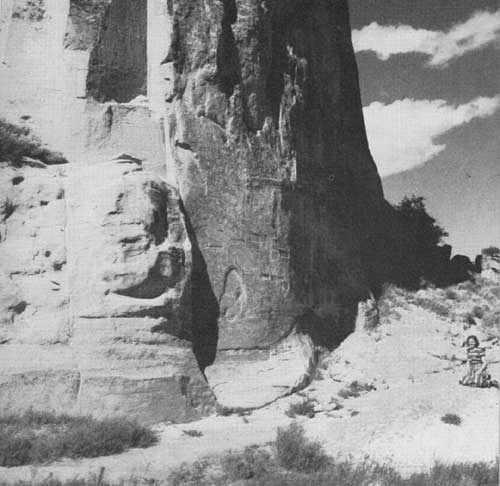

EL MORRO NATIONAL MONUMENT, situated in northwestern New Mexico, was established by proclamation of President Theodore Roosevelt on December 8, 1906, for the protection of the great mesa known as El Morro, or Inscription Rock. Carved into the soft sandstone at its base are hundreds of inscriptions, many of them of great historical importance, dating as far back as the year 1605. The monument area was increased in 1917 by Presidential proclamation to include prehistoric ruins of Zuni Indian origin located on top of the mesa; the present area is 240 acres.

The Inscription Rock is composed of Navajo sandstone, pale buff in color, with a capping of Dakota sandstone. The Navajo sandstone overlies the Chin Lee shales or Painted Desert formation.

The monument derives its name from the Spanish word "morro," meaning "headland" or "bluff." Rising 200 feet above the valley in which it is situated, the rock forms a striking landmark. From its rugged summit rain and melted snow drain into a large natural basin below, creating a constant, dependable supply of water. The road from Acoma to the Zuni pueblos led directly past the mesa. It became a regular camping spot for the Spanish Conquistadores and, later on, for American travelers to the west, all of whom found in its sheltered coves protection from Indian attack, and at the pool plenty of good water in a region where water was scarce.

The northeast point of Inscription Rock |

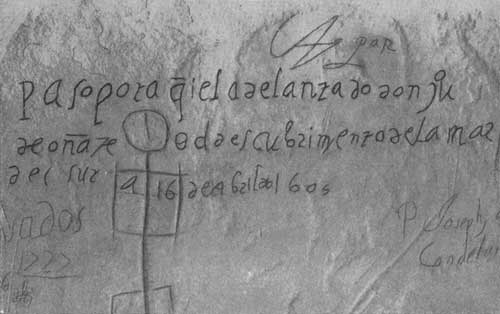

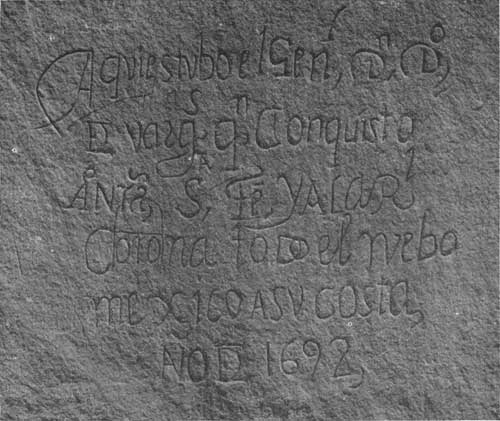

Oñate's inscription, dated 1605, the oldest recording on El Morro |

First Discovery by Americans

IN 1849 an expedition under Brevet Lt. Col. John M. Washington, chief of the 9th military department and Governor of New Mexico, set out from Santa Fe for the Canyon de Chelly, now a part of the national monument by that name in northeastern Arizona, on a military reconnaissance to the Navajo country. A treaty with the Navajos was consummated and the expedition was about to return to Santa Fe, when word was received that the pueblo of Zuni had been attacked by Apaches. Hoping to be of assistance to the friendly Zuni Indians, the expedition headed south, but learned upon reaching the pueblo that the rumor was false. The Governor and inhabitants of the pueblo greeted the soldiers warmly and, after a short visit, the return trip to Santa Fe was resumed.

The expedition passed near El Morro, and several of its members under Lt. J. H. Simpson, of the Topographical Engineers, were guided to the rock by an Indian trader named Lewis. They were amazed to find, scratched into the sandstone mesa at about the height of a man's shoulder, many Spanish inscriptions. Sketches were made by the artist R. H. Kern, one of Lieutenant Simpson's companions, and Simpson's report on the expedition, illustrated with lithographic reproductions of Kern's drawings, was later made a Senate document.

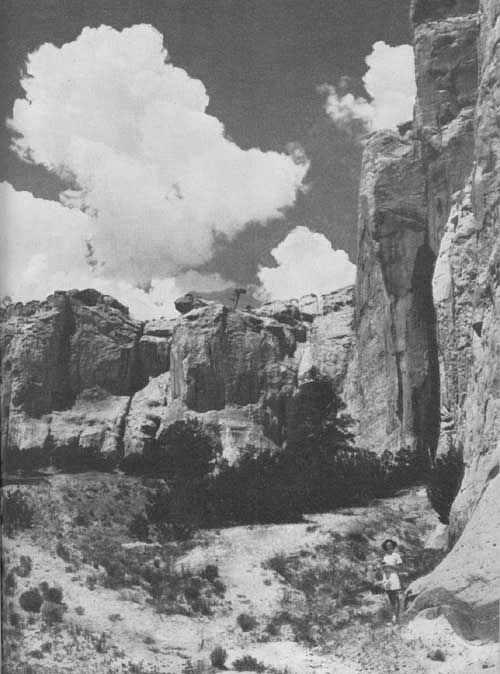

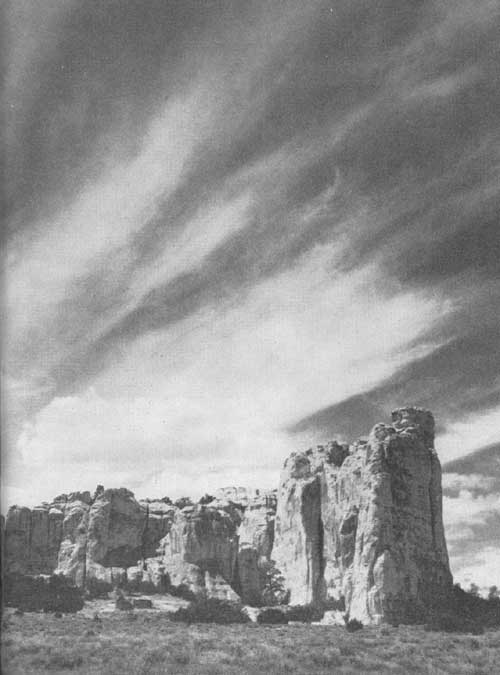

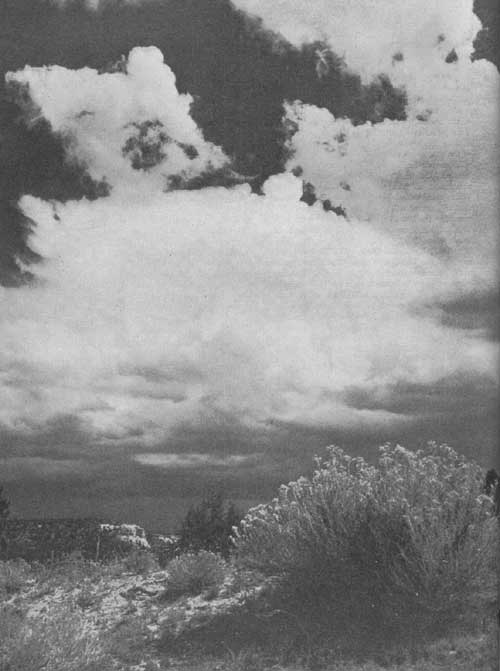

Great snow-white clouds in the deep blue sky hover over El Morro |

The "Seven Cities of Cibola"

IN THE YEAR 1539, the mythical "Seven Cities," long the subject of Spanish legend, crystallized in the minds of the Spaniards in Mexico into "The Seven Cities of Cibola." For some time stories had filtered into Mexico of the existence of six or seven walled cities far to the north. Their greed and imaginations inflamed by past conquests in Peru and Mexico, the Spaniards began to dream of discovering these cities and the hoards of gold and jewels they were believed to contain.

Looking down into the canyon from the top of El Morro |

General de Vargas left this carefully carved inscription on The Rock in 1692 |

First rumors of large towns to the north were brought to Mexico City in 1536 by the four survivors of the Florida expedition of Pámfilo de Narváez which had set sail from Spain in 1527. Their original number had steadily decreased because of desertions and death until in 1528, after numerous disasters, less than a hundred survivors were shipwrecked on a small island off the Texas coast. Further hardships reduced the party to a mere handful of men who succeeded in reaching the mainland, only to be captured by the Indians. Four of them—Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca, Alonso del Castillo Maldonado, Andrés Dorantes de Carranza, and a Negro slave, Estevan, managed to escape.

After a remarkable journey on foot, they reached Mexico City and told Viceroy Mendoza of rumors of large villages to the north.

Several years later, the Viceroy commissioned Fray Marcos de Niza, a Franciscan, to lead an expedition into this northern country in an attempt to find the cities and claim them in the name of the Viceroy.

The party left Culiacan in 1539, guided by the slave, Estevan. Going ahead of the expedition in order to obtain information about the country, Estevan sent back to Fray Marcos, who was following, news that was electrifying: that he had met people who had been to the "seven cities," one of which was called "Cibola."

Continuing on in advance of Fray Marcos and his party, Estevan reached "Cibola," only to be taken prisoner and killed. Word was brought back to Fray Marcos of Estevan's death, but the friar, undaunted, kept on: ". . . I continued my journey till I came within sight of Cibola. It is situated on a level stretch on the brow of a roundish hill. It appears to be a very beautiful city, the best that I have seen in these parts; the houses are of the type that the Indians described to me, all of stone, with their stories and terraces, as it appeared to me from a hill whence I could see it. The town is bigger than the city of Mexico. The Chiefs who were with me . . . told me that it was the least of the seven cities. . . . I made a big heap of stones and on top of it I placed a small slender cross, not having the materials to construct a bigger one. . . . I declared that I placed that cross and landmark in the name of Don Antonio de Mendoza, Viceroy and Governor of New Spain for the Emperor, our lord, in sign of possession, in conformity with my instructions. I declared that I took possession there of all the seven cities and of the kingdoms of Tontonteac and Acus and Marata, and that I did not go to them, in order that I might return to give an account of what I had done and seen. Then I started back, with much more fear than food. . ."

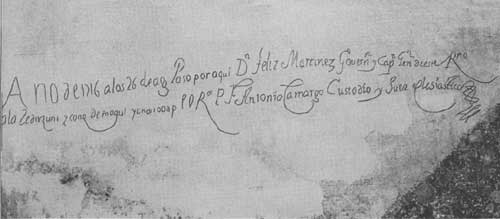

Don Feliz Martinez left a record of his conquests on El Morro in 1716 |

When de Niza returned to Mexico City, and news of his discoveries reached the ears of the people, the city went wild. Soon it was believed that the streets of Cibola were lined with shops of silversmiths and that gold and jewels were to be had in abundance.

In 1540, Francisco Vasquez de Coronado, led by Fray Marcos, set forth with his great army to explore further the northern country. With the friar as guide, Coronado and about a hundred of his men went in advance of the main army and reached "Cibola." Their disillusionment knew no bounds when they found the "beautiful city, bigger than the city of Mexico" to be the Zuni farming village of Hawikuh, with a population of about 500 families.

Coronado and his men were greatly in need of food and sent word to the Zunis that they intended them no harm. The Indians, however, came out in force and attacked the little party, whereupon a battle ensued. Although Coronado and his men emerged the victors and captured the town, they found no gold or jewels there. Casteñda, the chronicler of the expedition, wrote that "such were the curses that some hurled at Fray Marcos that I pray God may protect him from them." Fray Marcos found it expedient to return to Mexico.

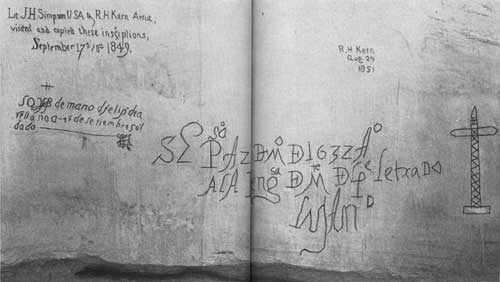

The Lujan inscription of 1632 |

Lured on and on by the fantastic tales of their Indian guide, whom they called "The Turk" ("because he looked like one"), Coronado and his party journeyed northeastward. The Turk told stories of cities where "everyone had their ordinary dishes made of wrought plate, and the jugs and bowls were of gold."

Only when they had trekked far into the plains country of present day Kansas did their guide confess that he had led them on with these fabulous tales "so that the horses would die when their provisions gave out, and they would be so weak if they ever returned that they could be killed without any trouble." The Turk was garroted, and the weary band turned back toward Mexico. Taking a short cut, Coronado was first to travel over the famous Santa Fe Trail.

Their expedition was one of the most remarkable in the history of the continent. While they did not find the riches they sought, they made discoveries of great importance and brought back a wealth of knowledge of the northern country and its peoples.

Inscription made on a military reconnaissance of the region |

Colonization of the New Mexico and First Inscription on El Morro

IN 1598, under Gen. Don Juan de Oñate, there was founded near the junction of the Chama River and the Rio Grande the first little Spanish colony. However, San Juan de los Caballeros as it was named, did not prosper, and many of the colonists returned to Mexico.

Oñate's explorations from his colony led him far afield. In 1604, he conducted a tour of exploration to the west, ultimately coming to the lower part of the Colorado River which he descended to its mouth. On his return, he passed El Morro, where he carved into The Rock the earliest inscription to be found there today. Translated, it reads: "Passed by here the Adelantado Don Juan de Oñate, from the discovery of the Sea of the South, the 16th of April of 1605."

Oñate's "Sea of the South" was the Gulf of California.

There was an intimate bond between the Zuni villages and El Morro. The Rock became a regular stopping place and camping ground for those who passed to and from Zuni. A well-traveled road was developed past The Rock, leading from the Zuni towns to the west to Acoma and Santa Fe to the east.

Approaching El Morro today from the east, the traveler rounds the point of a mesa a mile and a half distant, and the great rock comes into view, its pale bulk thrust sharply up into the blue New Mexico sky.

Toward this desert oasis marched the Spanish Conquistadores, soldiers, and missionaries, to refresh themselves and their mounts at the water pool and make camp beneath the pines before resuming their journeys.

Oñate's inscription probably inspired others to leave a record of their exploits, and as the years passed, more and more legends were inscribed on The Rock.

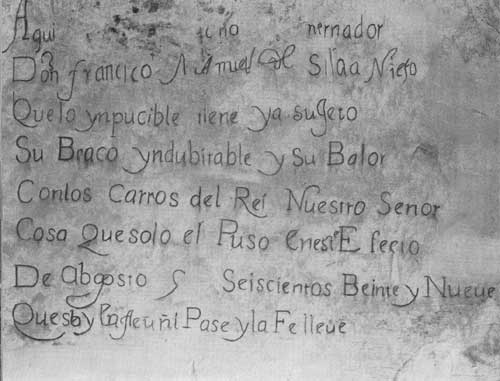

Nieto's record of his expedition in rhyme |

First Mission at Zuni

IN THE YEAR 1629, under Governor de Silva Nieto, the first Franciscan mission was established at Zuni. This was not the present pueblo of Zuni, but Hawikuh, the village said to have been seen by Fray Marcos, and later taken by Coronado. Carved into the stone on the north side of El Morro appears Nieto's inscription referring to his expedition. He left his record in the form of a poem, and while a literal translation into English will not rhyme, it reads as follows:

"Here was the Governor

Don Francisco Manuel de Silva Nieto

Whose indubitable arm and whose valor

Have now overcome the impossible

With the wagons of the King, our lord

A thing he alone put into this effect

August (obliteration) six hundred and twenty nine

That one may well to Zuni pass and the Faith carry."

But the life of the missionaries was not an easy one. Serenity did not prevail in the scattered Indian towns where the friars established outposts of the Church. A short distance from Nieto's inscription is another which deals with the mission at Hawikuh. Signed "Lujan," it reads: "They passed on the 23rd of March of the year 1632 to the avenging of the death of Father Letrado."

Fray Francisco Letrado, missionary martyr to his faith, was killed at Hawikuh on February 22, 1632, a hundred years before the birth of George Washington. Refusing to obey his call to mass, the Indians surrounded and murdered him, saving his scalp for use in their ceremonies. Lujan's inscription marks the passage past El Morro of the punitive expedition sent against the Zunis to avenge Father Letrado's murder.

When the soldiers arrived at Hawikuh the Zunis had already fled, deserting their village to seek refuge atop the great mesa of Towayalane, which was reached by difficult trails.

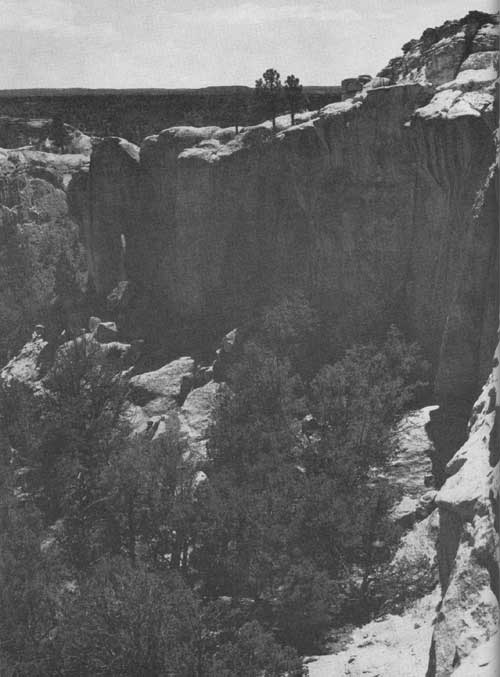

The deep rincon separates the two large surface ruins on the summit of El Moro |

Revolt of the Pueblos

BLOODSHED and violence were the order of the day, with the Indians hopelessly outclassed in battle from the very outset. Until the coming of the Spaniards they had never seen horses. While the intruders wore mail and armor and carried harquebuses and swords, the Indians were armed only with bows and arrows and spears. Their submission to the Spaniards was inevitable, but they always must have dreamed of the time when they would shake off the Spanish yoke.

At last a leader, a San Juan Indian named Pope, arose to liberate his people. For years, secret plans were made for a rebellion, which they plotted to spring suddenly and thus annihilate the Spaniards in the Southwest. But the Spaniards in some way received a short advance warning.

The revolt flared up during the month of August 1680, and the Spaniards were driven from their outposts back into Santa Fe. Under Governor Otermin they ventured out from the city against the ever-increasing army of besiegers, but finally realizing the hopelessness of their position, they abandoned Santa Fe and retreated to Mexico.

For 12 years the Spanish hold on The New Mexico was lost. Several attempts to reestablish their rule over the land failed, and the Indians once more maintained their own country.

Popé's rule, however, proved as disastrous as that of the hated Spaniards. Drunk with power, he set himself up as a deity, and it was not long before the New Mexico territory was torn with internal strife and dissatisfaction. The chaos that resulted from Popé's leadership was probably an important factor in the final easy reconquest by the Spaniards in its initial stages.

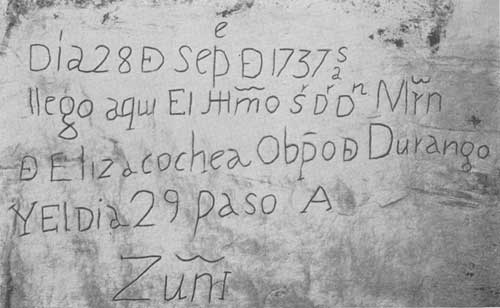

On his way to Zuni, the Bishop of Durango paused to record his journey at El Morro 1737 |

Reconquest of the Pueblos

THE FIRST stage in the Spanish reconquest came in 1692, when Gen. Don Diego de Vargas, with a small body of men, marched into New Mexico, meeting with little resistance at one pueblo after another. Acoma, Zuni, and the Hopi towns submitted with little struggle, and de Vargas returned to El Paso in December, having "conquered all of New Mexico" without bloodshed among the Pueblos.

On the south side of El Morro appears de Vargas inscription: "Here was the General Don Diego de Vargas, who conquered to our Holy Faith and to the Royal Crown all of the New Mexico at his own expense, year of 1692."

The country which de Vargas entered was one of desolation and ruin. Entire villages had been destroyed in the 1680 rebellion, missions had been burned, and attempts had been made to wipe out all traces of Christianity. Hawikuh and other Zuni villages lay abandoned and in ruins. But when the Spaniards reentered the country, following de Vargas' initial expedition, they encountered opposition on the part of many of the Indians who had submitted to the general. The actual reconquest of New Mexico, therefore, took nearly 15 years, during which time bloodshed and violence again spread throughout the country.

In 1716, Gov. Don Feliz Martinez marched against the Moqui (Hopi) villages. With him were missionaries who intended to "convert" the Indians after they were conquered. Passing El Morro, Martinez left the following inscription: "Year of 1716 on the 26 of August passed by here the Governor Don Feliz Martinez, Governor and Captain-General of this Realm to the reduction and conquest of Moqui and (obliteration: possibly the word "conversion") by order of the Reverend Padre Friar Antonio Camargo, Custodian and Ecclesiastical Judge."

But the expedition was not successful. Meeting strong opposition from the Hopis, Martinez merely destroyed their cornfields and returned to Santa Fe. He was later relieved of his office as Governor.

Looking west toward El Morro. The Rock stands out boldly above the surrounding desert |

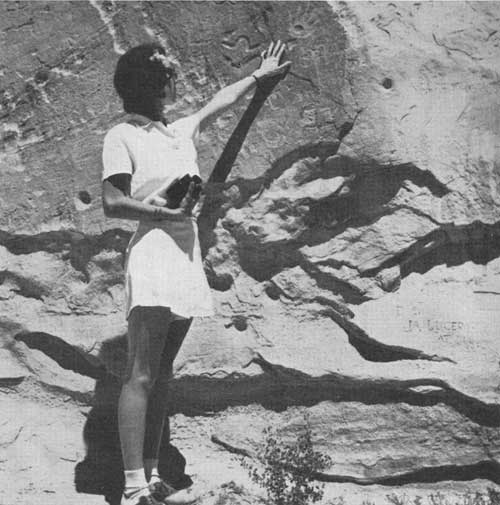

A visitor points to petroglyphs inscribed on the walls of The Rock |

American Inscriptions

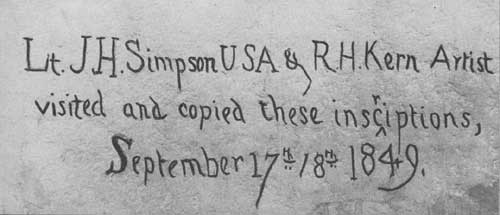

OTHER Spanish inscriptions appear upon The Rock, the last dated 1774. Then occurs a gap in dates until the year 1836. The initials "O. R," dated March 19, 1836, were found by Lieutenant Simpson upon the occasion of his visit to El Morro in 1849, but nothing is known of the author of this, the first inscription to bear an English date. The artist, R. H. Kern, who accompanied Simpson carved a record of their visit: "Lt. J. H. Simpson USA & R. H. Kern Artist, visited and copied these inscriptions, September 17th, 18th, 1849."

Then came names by the hundreds; emigrants, traders, Indian agents, American troops, surveyors, settlers—all paused to leave a record of their journeys on the massive walls of The Rock.

One of the names of special interest is that of Lieutenant Beale who, prior to the outbreak of the War between the States, commanded Uncle Sam's camel corps. In 1856 and 1857, 75 camels and dromedaries were imported from the Far East to furnish transportation across the arid plains of the West. The animals received praise from some and condemnation from others, the latter principally Army "mule-skinners."

With the outbreak of the Civil War, a number of the camels were seized by the Confederates in Texas, and many escaped from captivity. Some of the animals wandered far afield, and at the close of the nineteenth century reports were received of wild camels having been seen in Arizona and Mexico. Others, in captivity, were sold at auction; most of them went to circuses and zoos. While even today reports occasionally are heard that wild camels still roam the West, it is probably true that the last of them died many years ago. The skeleton of one is in the National Museum in Washington, D. C.

In 1857, Lieutenant Beale established a wagon route to the West, and upon The Rock appear many names carved by members of the first emigrant party to attempt to reach California by this route. The party, numbering nearly a hundred persons from midwestern States, reached El Morro on July 7, 1858, and camped overnight. The following day they resumed their slow march to the West.

Reaching the Colorado River, they prepared to snake the crossing, when misfortune struck in the form of a sudden attack by Mojave Indians. During the fight that ensued, seven of the travelers were killed and others badly wounded. When the Indians had been driven off, the emigrants took stock of their situation and found it appalling. Of nearly 400 head of livestock they had saved but 17. They had lost their wagons and all their household effects and personal belongings.

Across the river lay California, but there, too waited the Mojaves. There was no use in attempting to go forward; the only road open to them was the road back. So, on foot, they began the long trek back to Albuquerque. Averaging about 5 miles a day, suffering untold hardships, they finally reached the city in October. They had started for California with high hopes; they had endured many hardships in the attempt to reach their destination. Now, in the words of one of their party, they found themselves "living beggars, or on the bounty of kind people, in a strange land and among strangers."

World's Largest Autograph Book

WHAT stories the old Rock could tell: For in addition to the inscriptions it bears, there are other evidences of long-forgotten civilizations, of ancient lives and adventures.

On the very top of El Morro lie ruins of Zuni Indian pueblos, abandoned long before the coming of the Spaniards. Broken pottery is strewn about. These ruins, as yet unexcavated, are covered with the growth of centuries, but here and there a bit of wall, still standing, speaks of the culture that once flourished here. Carved into the sandstone on The Rock itself are also hundreds of petroglyphs left by these ancient people. Prehistoric hand and foot trails lead down the face of The Rock to the pool at its base. Long after the pueblos were abandoned, the Conquistadores came to this same pool, leaving inscriptions on The Rock. Following the Spainards came the American pioneers, who also paused to refresh themselves at El Morro and leave their names on its walls.

El Morro may well be called a massive book whose pages are engraved with the history of a great nation in the making.

Administration

A RESIDENT custodian is stationed at El Morro the year around. A fee of 25 cents is charged those over 16 years of age, and ranger service is furnished all visitors. During the winter months the monument is usually isolated, owing to snow-covered roads. The visitor season is from mid-April to November. The monument is reached by dirt roads from Gallup, N. Mex., 60 miles northwest of El Morro, or from Grants, N. Mex., 40 miles to the east.

There are no developed campgrounds at the monument, but the visitor may easily make the trip to El Morro from either Gallup or Grants, take a guided trip around The Rock, and return in less than a day. Thirty-six miles to the west, the pueblo of Zuni is of absorbing interest; to the east, about 18 miles, vast lava flows and ice caves await exploration. Across the New Mexico-Arizona line lie the great Painted Desert, Petrified Forest, and other intriguing areas rich in history and scenic beauty, and included in the national park system.

On back cover: Looking south over the desert from El Morro |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> |

1941/elmo/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 20-Jun-2010