|

FORT McHENRY

Guidebook 1940 |

|

|

FORT McHENRY NATIONAL MONUMENT AND HISTORIC SHRINE |

FORT MCHENRY National Monument and Historic Shrine, 47 acres in area, is located about 3 miles from the center of the city of Baltimore and is within its corporate limits. The central feature of the area is the Star Fort, or Fort McHenry proper, with its five bastions forming a five-pointed star. Within the fort are museum exhibits pertaining to its history, events of the War of 1812, and The Star Spangled Banner. Also on exhibit are pieces from the Bowie collection of weapons, showing the development of firearms from the seventeenth century to the World War of 1914-18.

The composition of The Star Spangled Banner and the successful defense of Fort McHenry against the British bombardment of September 13-14, 1814, which inspired Francis Scott Key to write the poem, are the historic events commemorated by this shrine, events which take high place in American tradition.

By Act of Congress, approved March 3, 1925, Fort McHenry was set aside as a "national park and perpetual national memorial shrine as the birthplace of the immortal Star Spangled Banner," to be administered under the custody of the Secretary of War. This Act provided for the restoration of Fort McHenry as nearly as practicable to its appearance during the War of 1812. The restoration was undertaken by the War Department; many new buildings and structures erected during the World War were removed, and others were altered to conform approximately to their appearance in 1814. Fort McHenry was under the administration of the War Department until 1933 when, with many other historic sites in Federal ownership, it was transferred by Presidential proclamation to the Department of the Interior for administration by the National Park Service.

By Act of Congress, approved August 11, 1939, the designation of the Fort McHenry area was changed to "Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine."

The Armistead statue looks out over Baltimore Harbor from Fort McHenry. |

WHETSTONE POINT AND FORT MCHENRY 1775-1814

FORT MCHENRY is on the tip of a peninsula formed by the Northwest and Ferry branches of the Patapsco River, which constitutes Baltimore's harbors. Whetstone Point, the first name known to have been given to the site, was early recognized for its military importance. From the first years of the American Revolution, the point, commanding the two narrow channels (500 and 1,500 yards wide) through which it was necessary for ships to pass to reach Baltimore, was looked upon as a natural position for defense. Early in the Revolutionary War, the provincial convention of Maryland ordered the construction of fortifications, and they were begun in 1775. The following year, when British vessels threatened the city, a small 18-gun fort was constructed there by the little town for the protection of its 5,000 inhabitants. Fort Whetstone, as it was named, was never called into action.

Baltimore grew rapidly to be a city of importance during the early years of the Republic. In 1794 it was listed among 17 other ports for harbor fortifications to be constructed by the Federal Government, already preparing to defend its long coast line. In that year the initial appropriation was made for the erection of a fort. Meanwhile, the citizens of Baltimore, at their own expense, began the erection of a new star fort of masonry in the rear of old Fort Whetstone and about 400 or 500 feet back from the water's edge, on ground which belonged to private citizens and to the State of Maryland. The design of the fort was drawn and its construction supervised by Maj. J. J. Ulrich Rivardi, a French army officer.

By authority of an Act of Congress of March 20, 1794, the Legislature of Maryland having given its consent, the incompleted fort passed under the control of the Federal Government. The works were completed in 1805, but the Government continued to make various improvements at Fort McHenry up to and through the War of 1812. The formal cession of the fort and adjacent land to the United States by the Maryland Legislature did not take place, however, until 1816.

Before 1800 the fort had already been named McHenry, in honor of James McHenry, of Maryland, a native of County Antrim in Northern Ireland.

He was born about 1753, and as a youth emigrated to America, where he studied medicine under Dr. Benjamin Rush of Philadelphia. An ardent patriot, he enlisted in the American forces in 1775, serving first as army surgeon and later as secretary to General Washington. After the Revolution he was prominent in the Federalist party of Maryland. In January 1796 Washington made him Secretary of War, a position he held until 1800.

Two visitors about to go through the sally port, the only entrance to the Star Fort, Fort McHenry. The cannon at left is of the type used in the War of 1812 |

THE BOMBARDMENT OF FORT MCHENRY

SOON after the beginning of the War of 1812, the British blockaded Chesapeake Bay, a strategy adopted largely because of the activity of privateers sailing from Baltimore Harbor and the inconvenience to the United States of having a leading exporting and importing center closed. It was not until 2 years later, however, after the blockading fleet had been greatly reinforced, that the British attempted, in what has become known as the Chesapeake Bay Campaign, to capture Washington and Baltimore.

The movement against Washington in August 1814 was successful, and the Capitol and White House were burned. The city's untrained militia proved no match for the veteran British troops when they met at Bladensburg, Md., just east of Washington, on August 24, 1814.

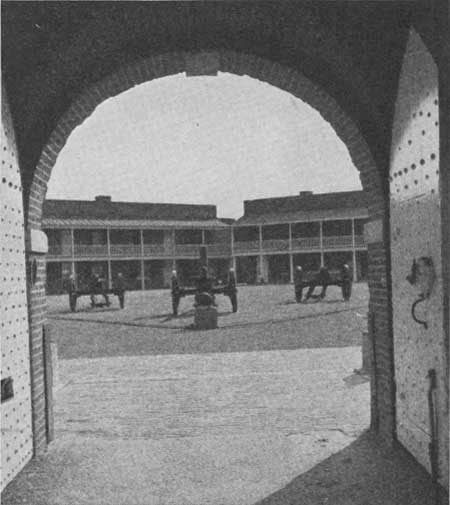

Looking through sally port toward interior of Star Fort. Mounted cannon of the War of 1812 type. Barracks buildings in the background. |

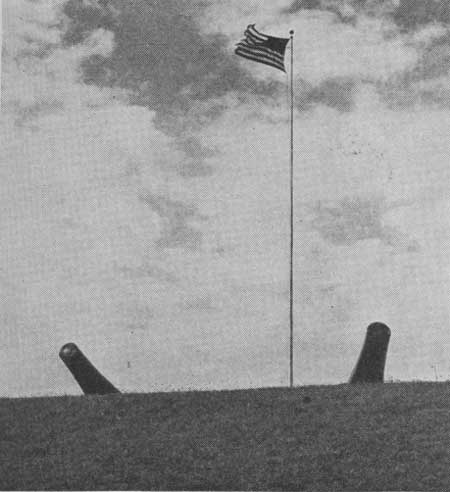

The muzzles of two guns flank the Stars and Stripes as seen from the outer walls of Fort McHenry. |

The attack against Baltimore 3 weeks later was the conflict in which Fort McHenry took a prominent part, and for which it is remembered today.

The British fleet and the infantry troops which executed the movements against the two cities were commanded, respectively, by Adm. Alexander Cochrane and Gen. Robert Ross. At the time of the attack against Baltimore the defense forces in and around the city numbered approximately 12,000 men, assembled from various parts of Maryland, Virginia, and Pennsylvania, and commanded by Gen. Samuel Smith.

The British threat to the Chesapeake region in 1814 caused considerable excitement in Baltimore. As there was no money available from the Federal Government for local defense, the City Council mobilized every able-bodied citizen with his slaves and any equipment he might own to help in the construction of earthworks and gun emplacements. The works at Fort McHenry were strengthened, ship hulks were sunk in the river channels leading to the city, as an obstruction to enemy vessels, and fortifications were thrown up on the outskirts of the town to protect it against land attacks. West of the fort, two redoubts named Forts Covington and Babcock were erected 500 yards apart to guard the middle of the Patapsco River against the landing of troops operating to assault Fort McHenry from the rear. On the high ground behind these redoubts was the "Circular Battery." A long line of platforms for guns was erected in front of the fort; it constituted the water battery. In addition, a number of 42-pounders were borrowed from a French frigate in the harbor and mounted in the water battery. These were the heaviest guns in the fort.

A report, dated December 1, 1813, on the state of the fortifications in the harbor of Baltimore, contains the statement that "Fort McHenry has now mounted 21 guns: 24s, 18s, and 12-pounders. The water batteries contiguous contain 36 guns, 15 of which are of the largest calibre, the rest 24- and 18s." These, with such guns as were temporarily placed just before the bombardment, undoubtedly constituted the battery at the fort on September 13-14, 1814.

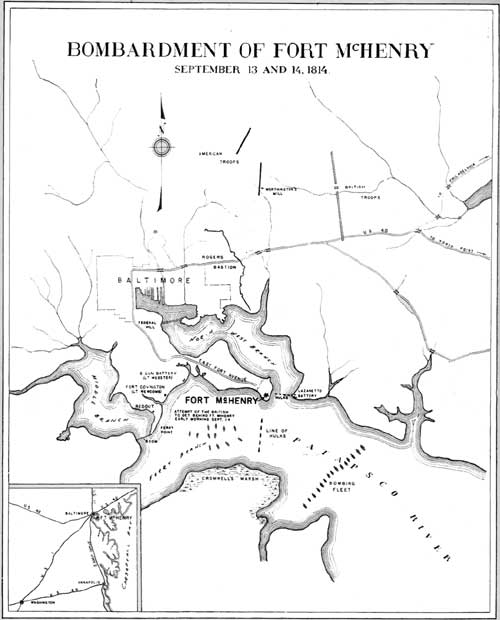

On September 11 the enemy fleet arrived at the mouth of the Patapsco River, a few miles by water from Fort McHenry. Here, at North Point, the British landed between 4,000 and 5,000 men the next day. They were ordered to advance northwest against Baltimore's land fortifications in co-ordination with a movement to be made by the fleet up the Patapsco against the harbor defense position. The cooperating units, moving parallel by land and water, planned to enter the city at the same time.

Soon after the land forces began their march toward Baltimore, General Ross, their commander, was fired upon from ambush and mortally wounded. Under the command of Col. Arthur Brooks the advance was continued, and at a point about 5 miles from the city the British were met by the Maryland brigade commanded by Gen. John Stricker.

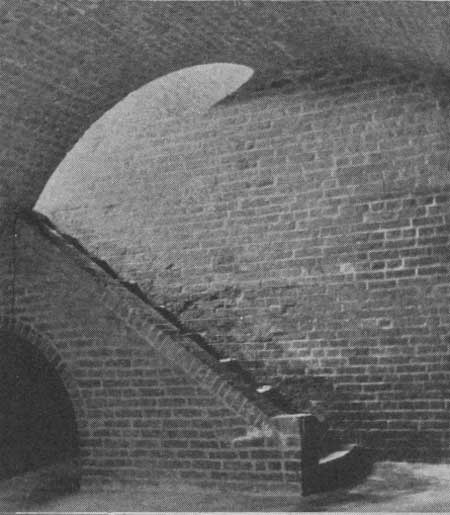

Stairway, arch, and walls of one of the magazines at Fort McHenry. |

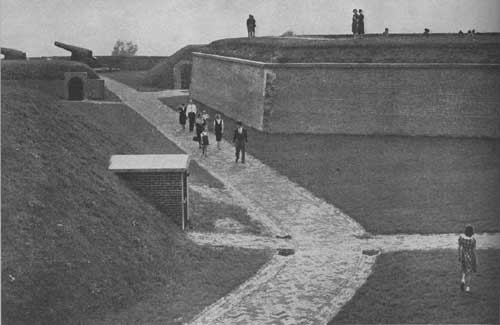

A general view of Fort McHenry showing one of the five bastions of the fort and a section of the outer works. |

The short engagement which ensued during the early afternoon is called the Battle of North Point. It was little more than an attempt to retard the British advance, for Stricker's forces were hardly sufficient to defeat the more experienced soldiers whom they opposed. About an hour and a quarter after the opening shots were fired the American troops retreated to their main defense line around the city, followed by the British infantry. Facing the Baltimore defenders, not more than 2 miles from the city limits, the British army awaited the outcome of the naval attack.

During the evening and night of September 12, 16 British vessels moved up the Patapsco, and by morning of the 13th were in position about 2 miles from Fort McHenry at a point sufficiently close for the English guns to reach their objective, and yet beyond the range of the smaller guns of the fort. The Patapsco had not yet been dredged, and shallow water would have been a menace to the larger ships if a closer approach had been attempted.

Maj. George Armistead, in command of the garrison of 1,000 regulars, militiamen, and sailors at the fort, placed his own artillery, with one company of volunteers, in position inside the fort. The remainder of the artillery and infantry was stationed in the outer works along the waterfront.

The bombardment of Fort McHenry began about daylight on September 13 and lasted until about 7 a. m. of the following day. According to British accounts, well over a thousand shells and bombs were fired. The shorter range artillery in the fort did little more than fire sufficiently to indicate that the position had not fallen. According to eyewitnesses, only four bombs actually burst within the fort. One of these fell in the southwest bastion during the afternoon, killing a lieutenant and wounding several men. In all, only four men were killed and about 24 wounded at Fort McHenry during the bombardment; the buildings apparently were but slightly damaged.

On the night of the 13th, when it became obvious that the position could not be taken by bombardment, Admiral Cochrane sent forward by way of the main branch of the Patapsco River a force of approximately 1,200 men, hoping to take the fort by land. After midnight, under cover of darkness, the landing party was able to reach the channel behind the fort, but was soon afterward observed and identified by pickets. A galling fire was at once opened from the fort and the smaller Fort Covington and other battery positions in the rear, causing the British to abandon the projected maneuver before the party had reached land.

At about 7 o'clock on the morning of September 14, the bombardment ceased. By 9 the fleet had begun to withdraw down the river. Colonel Brooke, in command of the land force, was notified of the failure to reach Baltimore by water, and his troops were ordered back to North Point. There, joined by the fleet, the infantry reembarked and Admiral Cochrane directed his fleet out of the Chesapeake Bay, part proceeding to the base at Halifax, Nova Scotia, and the rest going to the West Indies, where the expedition against New Orleans was being assembled.

The successful repulse of so strongly organized an attack had a tremendous effect upon the spirit of the American people, discouraged by the disaster at Bladensburg and the capture of Washington only 3 weeks before.

THE STAR SPANGLED BANNER

THE CIRCUMSTANCES that led to the writing of The Star Spangled Banner by Francis Scott Key have their origin in the events which followed the British attack on the Capital. The enemy fleet had anchored in the Patuxent River, and the attacking force had proceeded overland to Washington. Following the burning of the Federal buildings in Washington, the British returned to their base on the Patuxent, while raiding parties and stragglers roamed the nearby countryside.

The appearance of returning British troops at Upper Marlboro, a Maryland town about 15 miles east of Washington, led to speculation by some of the inhabitants on the result of the expedition.

Dr. William Beanes and a group of his friends were enjoying a social hour when three British stragglers appeared. After an argument between the soldiers and Dr. Beanes and his companions, the stragglers were arrested on charges of disturbing the peace and placed in the local jail. One of them escaped and reached a scouting party of British cavalry which immediately marched to Upper Marlboro, captured Dr. Beanes and took him to the British base on the Patuxent, where he was turned over to Admiral Cochrane.

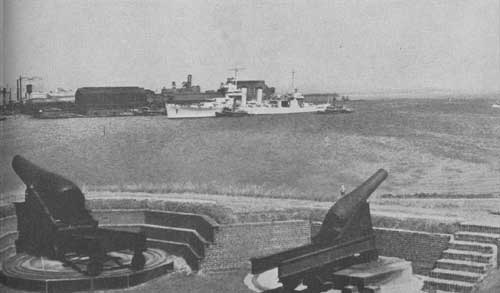

View from Star Fort looking over the outer ramparts and guns to Patapsco River and part of Baltimore Harbor. British ships bombarding the fort in 1814 were stationed in the harbor at extreme right of picture, about 2 miles distant. |

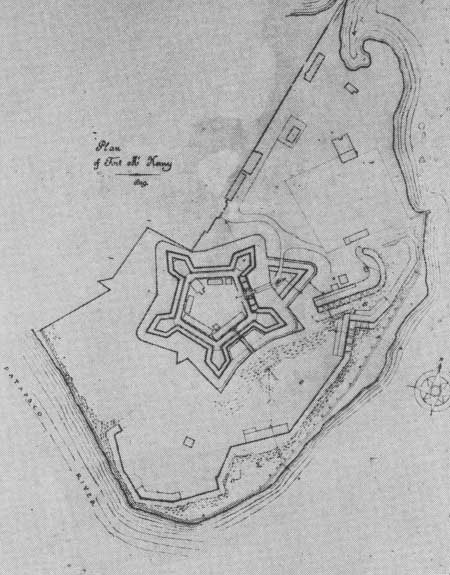

Plan of Fort McHenry made in 1819, showing the fort substantially as it must have been in 1814. |

Francis Scott Key, a prominent attorney of Georgetown (now part of the Capital) and a close friend of Dr. Beanes, undertook to effect his release. Obtaining President Madison's permission, Key and Col. J. S. Skinner, of Baltimore, agent for the exchange of prisoners, proceeded on a packet boat from Baltimore under a flag of truce and met the British fleet which was preparing to attack the city. Admiral Cochrane agreed to release Dr. Beanes, but refused to permit any of the Americans to return to the mainland until the movement against Baltimore had been carried out, since he did not want them to convey information of his plans to attack the city.

Taken aboard the Admiral's flagship, the Surprise, Key and his companions were compelled to accompany the British up the Patapsco River toward Baltimore.

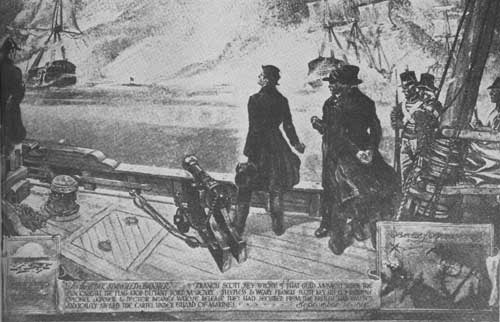

Under a guard of marines, the Americans were transferred to their own boat in the rear of the fleet as the British ships took their positions to bombard Fort McHenry. It was from this vantage point that Key witnessed the bombardment of the fort throughout the day of September 13 and the following night.

At dawn he saw that the American flag, the Stars and Stripes, was still flying over Fort McHenry and that the fortress and the city had not fallen to the British. That morning the attack was abandoned, and the British moved downstream toward the bay. Key and his friends were then released and allowed to make their way to Baltimore.

There are many versions of the story concerning the writing of The Star Spangled Banner, but perhaps the most reliable is that given in a preface to the 1857 edition of Key's poems by Roger B. Taney, Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court, who had married Key's only sister.

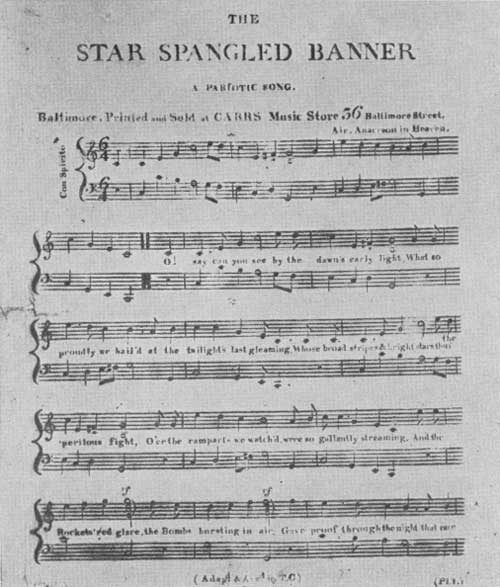

Taney states that the verses were written on an envelope as Key and his companions came ashore on the morning of September 14 and were rewritten in a hotel that night. The next morning Key showed the verses to Judge Joseph H. Nicholson, of Baltimore, his wife's brother-in-law. The judge was greatly impressed by the stirring quality of the poem, and his wife took the manuscript to the printing shop of Capt. Benjamin Edes on the corner of Baltimore and Gay Streets and had the poem run off in handbill form. Edes, it seems, was away at the time on duty with his regiment, and The Star Spangled Banner was set up and printed by a 12-year-old apprentice, Samuel Sands. On September 20 the poem was published in the Baltimore Patriot, and in a short time it was being sung in taverns throughout the land as an expression of American patriotism.

The Star Spangled Banner was first sung publicly by Ferdinand Durang, an actor, in Baltimore, to the old English tune of "To Anacreon in Heaven." This melody had previously been used in America for a song called "Adams and Liberty," of the Revolutionary War period. Key probably had the tune in mind when he composed The Star Spangled Banner.

Although the song was widely accepted at an early date as our national anthem, it was not until March 3, 1931, that Congress passed the necessary legislation formally recognizing this.

Francis Scott Key, a native of Frederick County, Maryland, was born on August 1, 1779, and was 35 years old when he composed the words that have made his name immortal. He died on January 11, 1843, and was buried in Mount Olivet Cemetery, Frederick. Monuments to him have been erected at Fort McHenry, at Eutaw Place in Baltimore, and at Golden Gate Park in San Francisco.

FORT MCHENRY, 1815-1925

AFTER THE WAR of 1812 the Government made a reconnaissance of the entire Atlantic coast. Included in the material submitted with the report on the Baltimore area was a detailed drawing of Fort McHenry which shows it approximately as it was in 1814. This map, drawn in 1819, is the best available for a study of the fort at the time of the British attack.

Although Fort McHenry continued to be used by the army from the close of the War of 1812 until 1912, the conflict of September 13-14, 1814, was the only occasion on which it came under enemy fire. During the succeeding American conflicts of the nineteenth century, however, it was used for military purposes; although no enemy moved against it. By midcentury Fort Carroll was being erected as the principal defense of Baltimore Harbor.

In the war with Mexico, Maryland troops were trained at Fort McHenry, and throughout the War between the States it was used as a prison camp and as headquarters of the military district. At times there were several hundred Confederate prisoners in the confines of the reservation.

The abandonment of Fort McHenry as a coast defense was suggested in 1820, and although it was used for nearly another century, it is improbable that it was seriously regarded as a military factor after 1877, when partially completed work was abandoned. Improvements in warships and cannon, and the expansion of Baltimore, made Fort McHenry useless as a military post.

The ownership and administration of the reservation changed several times between 1912 and 1933. In 1912 the site was leased by the Federal Government to the city to be used as a municipal park. In 1918 it was reclaimed by the Federal Government and used until 1925 as a general hospital. During the World War the fort and buildings about it constituted one of the largest hospitals in the country.

Field piece of War of 1812 period. The carriage is a reconstruction. |

|

|

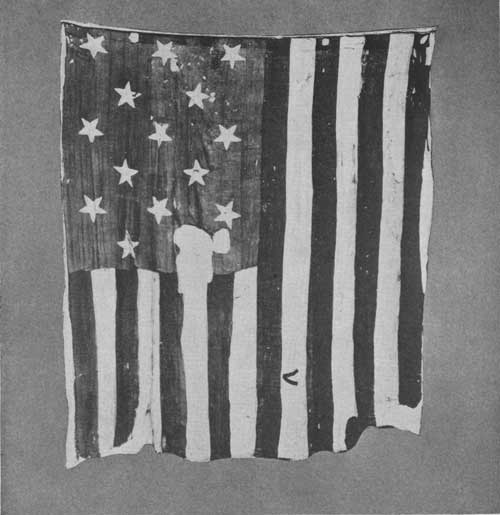

This flag, flown over Fort McHenry during the bombardment by the British fleet, September 13-14, 1814, is known as the "Star Spangled Banner." It is the flag which Francis Scott Key saw from his position about 3 miles out in the harbor on the morning of September 14, 1814, and which inspired him to write the verses that have since become the national anthem of the United States. The flag eventually was presented to Maj. George Armistead, who commanded Fort McHenry during the bombardment. Later, it became the property of his daughter, Georgianna Armistead, and in 1912 it was presented to the National Museum by her son, Eben Appleton. In addition to its great patriotic value as the source of inspiration for our national anthem, its historical importance is increased because of the fact that it is one of the very few United States flags still in existence having 15 stars and 15 stripes, the standard design from 1794 to 1818. It is said that several shots tore through the flag during the bombardment of Fort McHenry. Although many holes and tears are visible in the flag today, it is not possible to determine their origin. Several feet have been lost off the fly end of the flag. The remaining part of the "Star Spangled Banner," about 28 feet on hoist and 32 feet on fly, was quilted to a backing of Irish linen in 1914 for permanent preservation. This task was performed by a group of expert needlewomen under the direction of Mrs. Amelia Fowler of Boston, Mass. The flag is now on display in the North Hall of the Arts and Industries Building, National Museum, Washington, D. C., together with other military and naval relics of the War of 1812. Courtesy United States National Museum. |

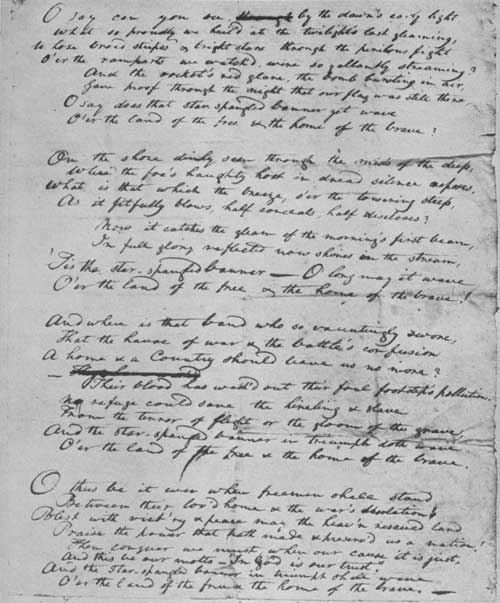

Facsimile of the manuscript draft of The Star Spangled Banner. Courtesy Walters Art Gallery. |

Facsimile of page one of the first printing of The Star Spangled Banner with music. |

FORT MCHENRY TODAY

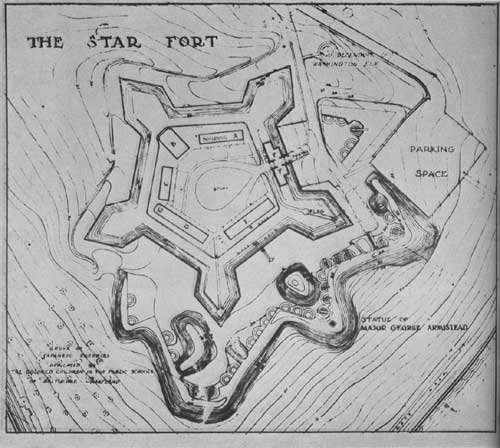

PHYSICALLY, the old fort is a fine example of the military architecture of the eighteenth century. It is laid out on the plan of a regular pentagon with a bastion at each angle, forming in effect a five-pointed star. A barbette work with brick masonry, it is scarp capped with a heavy projecting granite coping, the corners of the bastions being of sandstone.

Each front measures about 290 feet between the points of the bastions. The parade is a regular pentagon of about 150 feet on each side, surrounded by a well-laid granite wall about 5 feet high supporting the ravelin in front of which a brick masonry foundation about 3 feet high, with sandstone coping over sheet zinc, acts as a retaining wall for the curtain of sodded earth extending to the top of the scarped exterior parapet. The level of the parade is about 33 feet and the top of the bank above the scarped walls is about 45 feet above the mean low watermark. A wide ditch, 13 feet below the coping of the masonry wall, surrounds the fort. The ditch was never used as a water moat and, in fact, parts of it were never completed.

The fort is entered through an arched sally port which is flanked on both sides by bombproofs. Within the fort the buildings now used as museums may be identified as follows (see Plan, page 14): A—quarters for commanding officer and his adjutant or aide, B—the powder magazine with masonry walls and roof 13 feet thick, C—quarters for officers, D and E—barracks for troops.

From the ramparts near the flagstaff one can look down upon the Patapsco River where, in 1814, the British fleet was stationed during the historic bombardment.

Immediately opposite the sally port on the outside of the Star Fort is a detached triangular bastion of the same general appearance and construction as the main fort. This outer work served as additional protection to the fort entrance. Originally, the fort was entered by a wooden bridge reaching from this bastion to the sally port. Another bridge connected the bastion with the approach roadway. Under the bastion is a bombproof powder magazine.

Commencing near the detached bastion and extending most of the way around the fort is a dry moat. About 1850 a section of the moat on the side of the fort toward the river was converted into outer fortifications. Earthworks were constructed on the shoulder of the moat and coast defense guns were mounted. Underground ammunition magazines were constructed in the outer fortifications at that time.

Among the differences between the fort of 1814 and that of today, which approximates a restoration as far as practicable, the following may be noted: The brick retaining wall on the firing step was not present in 1814, the bastions were planked, the moat on the south or outer side was shallow, buildings A and E were not of the same dimensions as today, and buildings in the fort in 1814 were of one and a half stories. About 1830 the full second stories were added.

Portrait of Francis Scott Key by Charles Wilson Peale. Courtesy Philadelphia Academy of Fine Arts. |

In 1914, the 100th anniversary of the defense of Fort McHenry and of the composition of The Star Spangled Banner, Congress appropriated $75,000 for the erection of a monument "in memory of Francis Scott Key" and the soldiers and sailors who participated in the battle of North Point and in the defense of Fort McHenry during the War of 1812. In this year also the National Star Spangled Banner Association was given authority to erect a monument in memory of Maj. George Armistead. A monument of Key, an heroic bronze figure of Orpheus, was not completed until 1922 because of the World War. The Armistead monument is a bronze portrait figure standing on the southeast salient of the outer work.

MUSEUMS

THE BUILDINGS in the fort proper are now used principally for museum purposes. They are designated by letters A to E, beginning at the right of the entrance inside the fort. In 1936, the National Society of the Daughters of 1812 gave a collection of replicas of old furniture such as were probably used in the commanding officer's headquarters. This furniture is on display in Building A, which served as headquarters building during the bombardment of 1814. In 1935, the E. Berkley Bowie collection of weapons, consisting of about 400 pieces, was donated to the fort by the Maryland Society of 1812. The collection is now housed in Building D. In 1939, Mrs. Reuben Ross Holloway and Mr. John W. Farrell, of Baltimore, led a campaign to purchase for the fort the painting "'Tis the Star Spangled Banner." Their efforts were successful, and the painting now hangs in Building E, upstairs, where it is the central feature of the Star Spangled Banner Room. Downstairs in the same building is located a large relief map showing the position of the British fleet in relation to Fort McHenry and Baltimore during the bombardment. Other exhibits and relics are located in Buildings D and E.

Painting by George Grey showing Francis Scott Key as he looks toward Fort McHenry on the morning of September 14, 1814, and sees the flag still waving above the ramparts of the fort. This painting was purchased by public-spirited citizens of Baltimore and presented to the United States Government in 1939. It is now on display in the Star Spangled Room in Fort McHenry. |

General plan of the Star Fort and immediate environs, 1939. |

GENERAL INFORMATION

THE MONUMENT area is easily accessible from Baltimore, East Fort Avenue leading directly to the fort. Fort McHenry is open to the public from 7:30 a. m. to 5:30 p. m., while the museums close at 5 p. m. A fee of 10 cents for admission to the Star Fort is charged visitors more than 16 years of age, with the exception of members of school groups who are admitted free up to 18 years of age. Free guide service is available to all visitors. Organizations or groups will be given special service if arrangements are made in advance with the superintendent. All communications should be addressed to The Superintendent, Fort McHenry National Monument and Historic Shrine, Baltimore, Md.

Civil War period guns at Fort McHenry command Patapsco River at Baltimore Harbor. |

BOMBARDMENT OF FORT McHENRY — SEPTEMBER 13 AND 14, 1814

(click on image for a PDF version)

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> |

1940/fomc/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 20-Jun-2010