|

FORT PULASKI

Guidebook 1940 |

|

|

Fort Pulaski NATIONAL MONUMENT |

FORT PULASKI, on Cockspur Island at the mouth of the Savannah River, was established as a national monument October 15, 1924, by Presidential proclamation. Originally under the jurisdiction of the War Department, the fort and adjacent area were transferred in 1933 to the supervision of the National Park Service, United States Department of the Interior. The monument area now embraces over 427.39 acres on McQueens and Cockspur Islands. On the latter island is located the historic Georgia fortification, one of the best preserved of the large brick fortresses constructed by the United States Government as a coast defense in the first half of the nineteenth century. The fort structure, a splendid example of military architecture, is surrounded by a beautiful natural marsh and a wooded area in which are found many varieties of birds and semitropical plants.

Fort Pulaski is 17 miles east of Savannah, Ga., and may be reached from that city by way of Tybee Highway (U. S. Route 80). In May 1938, a new epoch was begun in the history of Cockspur Island when it was connected with Route 80 by means of a concrete bridge across the South Channel of the Savannah River. There is no regular public transportation service to Fort Pulaski, but visitors may make arrangements with private transportation companies in Savannah for means of conveyance to the national monument.

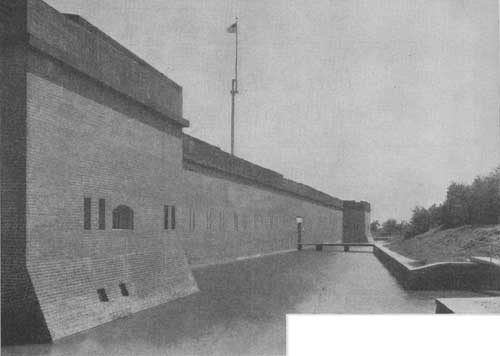

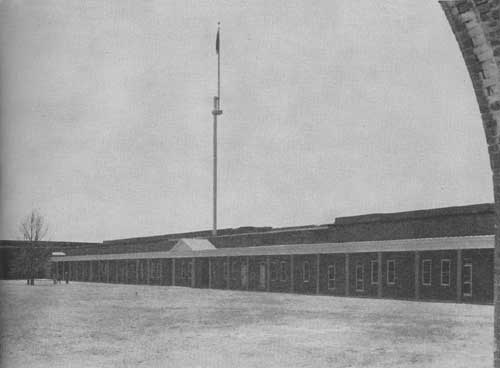

Historic Fort Pulaski is a five-sided brickwork, 1,580 feet in circumference, enclosing a parade ground two and one-half acres in extent and designed to mount two tiers of guns, one in the casemates or bombproof chambers, the other on the barbette or open platform on the top of the fort.

Its solid brick walls, from 7 to 11 feet thick and 32 feet high, are surrounded by a wide moat crossed by a drawbridge. Its long casemated galleries contain examples of some of the finest brick arch masonry in America. The red and gray brick, gray granite, and brown sandstone, of which the structure is built, lend charm and color to the old fort.

An intensive program of preservation, development, and interpretation has been in progress since 1933, utilizing Federal emergency funds and Civilian Conservation Corps labor under the technical supervision of the National Park Service. This project has consisted of the reconstruction of the natural area around the fort; the restoration of the dike and ditch system on the island; the provision of roads and parking facilities; and, in general, to make the area safe and accessible to visitors.

In order that the public may understand fully the historical significance of Fort Pulaski, Cockspur Island, and the immediate vicinity, a force of trained guides under the supervision of a National Park Service research technician is maintained to explain this interesting story. Supplementing this free service and further interpreting the area will be a museum exhibit, which is now being installed in certain of the barrack rooms within the fort.

Fort Pulaski National Monument is open to the public daily and Sundays throughout the year. From November through April the fort is open from 9:30 a. m. to 5:30 p. m.; from May through October the closing hour is 6:30 p. m. A fee of 10 cents for admission to the fort is charged visitors over 16 years of age, with the exception of members of school groups, who are admitted free up to 18 years of age.

Free guide service is available to all visitors, and special service for organizations or groups is given if arrangements are made in advance with the Superintendent. Communications upon any subject in regard to the area should be addressed to the Superintendent, Fort Pulaski National Monument, Savannah, Ga.

A broad moat surrounded the fort in the period of the War between the States in order to protect the garrison from land attack. |

Guns were mounted in the casemates, or tower sections of the fort, and on the terreplein, or upper platform. Doors, exactly like those on the casemates in the background, protected all the casemates during the War. |

The Story of Fort Pulaski

THE COLONIAL BACKGROUND

THE STRATEGIC location of Cockspur Island, serving commercial interests in peacetime and military purposes in time of war, led Georgia's early colonists to call the small marsh island in the mouth of the Savannah River "The Key to Our Province." Throughout the history of colony and state, the island has played a significant role in the economic development and military defense of coastal Georgia.

Past Cockspur Island, then called "Peeper," in February 1733 sailed the pioneer band of English settlers under Gen. James Oglethorpe to establish on Yamacraw Bluff, at the site of present-day Savannah, the feeble settlement which was to be the beginning of the thirteenth American colony. To this island John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, made a momentous visit two years later. Here it was, his journal records, that Wesley ". . . first set . . . foot on American ground." More important in the history of religion is the fact that, during this visit to Cockspur, Wesley engaged in serious theological discussions which seem to have planted the basic idea of Methodism in his mind.

Fearing an attack by their perennial enemies at St. Augustine during the French and Indian War, Colonial leaders advocated the construction of a fort on Cockspur Island to protect the growing port at Savannah. As a result Fort George, a palisaded log blockhouse and earthen fortification, was begun on Cockspur in 1761. This pioneer fortification upon Cockspur served as a protection for Savannah harbor and intermittently enforced quarantine and customs regulations until 1776, when it was abandoned upon the approach of the British fleet.

THE REVOLUTION AND POSTWAR ERA

Upon the arrival of the British fleet at the "Key to Our Province" Savannah was placed in a state of blockade, and Cockspur Island, under the formidable guns of the fleet, became a haven for Loyalists fleeing from Savannah. Among these was the Royal Governor, Sir James Wright, who escaped to the island on the night of February 11, 1776. As he carried with him the great seal of the Province, Cockspur Island became in the minds of the Loyalists the true capital of Georgia. After an unsuccessful attempt upon Savannah the British fleet withdrew from the river, and the story of Cockspur in the American Revolution was virtually at an end.

New defenses were needed for the protection of the young republic, and as a part of President George Washington's national defense policy for the United States a second fort was built, 1794 to 1795, on Cockspur Island, to protect Savannah harbor. Named Fort Greene in honor of the Revolutionary hero General Nathanael Greene, who had made his home after the war at Mulberry Grove Plantation near Savannah, this fortification consisted of a battery designed for six guns, and was constructed of timbers and earth and enclosed behind pickets. There was also a guardhouse for the garrison.

Unfortunately the history of Fort Greene was brief and tragic, for nine years later it was totally destroyed and part of the garrison was drowned in the equinoctial gale that swept Cockspur in September 1804. A quarter of a century was then to elapse before Cockspur Island was again to be selected as the site of a fortification to command the Savannah River.

THE BUILDING OF FORT PULASKI

The year 1815 was a turning point in American military history. The War of 1812 with England had demonstrated how deplorably weak were American defenses. On thousands of miles of coast line on the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico there was scarcely a fort.

In 1816 Congress created a military Board of Engineers for Seacoast Fortifications and set it up as a distinct branch of the Army. Brig. Gen. Simon Bernard, the famed military engineer of Napoleon, was commissioned in the Corps of Engineers and assigned to the Board, which was to devise a scheme for national defense. Though nominally just an assistant engineer on the new Board, he soon assumed its leadership. During the years 1817 to 1822 Bernard surveyed the entire American coast. Then he presented to Congress plans for a chain of forts that would stretch from Maine to Florida and from Florida to the mouth of the Mississippi.

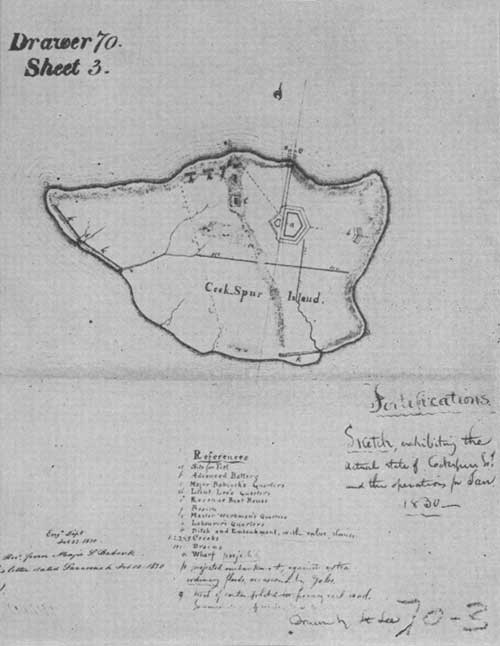

This sketch of Cockspur Island and Fort Pulaski was drawn in 1830 by Lt. Robert E. Lee, who was stationed there on his first tour of duty after graduating from West Point. |

Owing to its strategic location, commanding the South Atlantic coast and the Savannah River valley, Cockspur Island was chosen as the site of Fort Pulaski in the early 1820's; but actual work on the new fort was not begun until 1829. The original plans, dated 1827 and bearing the signature of Bernard, were not followed in detail. A number of important changes were made during actual construction.

Maj. Samuel Babcock, who was placed in charge of construction in 1828, was relieved of his duties because of ill health. To Lieutenant (later Captain) Mansfield, who served from 1831 to 1845, belongs chief credit for building the structure. His engineering ability, together with his energetic prosecution of the work in spite of the great difficulties that he encountered, resulted in a strong and well-constructed fortress. He was aided at times by young engineers serving their apprenticeship; the most promising of these was Robert E. Lee, whose first assignment after graduating from West Point was on Cockspur Island.

The work went on at Fort Pulaski more or less continuously from 1829 to 1847. It was an enormous project. Bricks were bought in lots of from 1 to 7 million at a time, and it is probable that as many as 25,000,000 were put into the structure. Lumber, lime, lead, iron, and other supplies were bought in proportionately large quantities.

In 1833 the new fort was named Pulaski in honor of the Polish hero, Count Casimir Pulaski, who fought in the American Revolution and was mortally wounded at the Battle of Savannah, 1779.

Nearly a million dollars was spent on Fort Pulaski, but in one respect it was never finished. Its armament was to include 146 guns, but at the beginning of the War between the States only 20 guns had been mounted, and even these were not serviceable until remounted. The fort was never garrisoned, and at the beginning of 1861 it was in charge of an ordnance sergeant.

THE BEGINNING OF THE WAR BETWEEN THE STATES

In November 1860 Lincoln was elected President. In the following month South Carolina seceded from the Union, and when Maj. Robert Anderson moved his Federal garrison secretly from Fort Moultrie to Fort Sumter, which blocked the harbor of Charleston, the South Carolinians seized Moultrie and the Federal arsenal. Savannah was thrown into a furor of excitement by this news, for if Fort Pulaski was also occupied by Federal troops entrance to that city would be blocked. Men and women held a mass meeting in the city, and they spoke of taking the fort. A day or two later Robert Toombs, a staunch Georgian, wired from Washington to Alexander H. Stephens: "Fort Pulaski is in danger." The people were so aroused by this information that they begged Gov. Joseph E. Brown to come to Savannah. On the evening of January 2, 1861, he issued the necessary order to take the fort.

Early the next morning, Col. Alexander R. Lawton went down the river aboard the little steamboat Ida at the head of about 125 volunteer troops from the First Georgia Regiment. No resistance was encountered; the keys to the fortress were handed over without protest. After celebrating the occasion, the men went to work to make the fort ready for defense. The old guns were remounted and new guns made in Virginia and Savannah were put in position during the ensuing months.

Georgia seceded from the Union on January 19, and on March 20 Fort Pulaski was transferred to the government of the Confederacy. Volunteer troops continued to serve at the fort until they were relieved by "regulars." Work at the fort went on throughout the year.

It has been estimated that more than 25,000,000 bricks were used in the construction of the fort. This view through the casemates shows the typical arch construction, a superb example of fine masonry. |

SIEGE AND BOMBARDMENT OF FORT PULASKI

By midsummer, 1861, the North had planned the campaign that led to the fall of Fort Pulaski. This plan embraced the reduction of all forts on the South Atlantic and Gulf coasts and the blockading of all southern ports. In September a great fleet set sail from New York. The expedition, after encountering a storm off Cape Hatteras, rendezvoused off Port Royal Sound, South Carolina, captured Hilton Head Island on November 7 and Port Royal a few days later. From these vantage points within 10 miles of Cockspur Island the Federal troops were ready to strike at Fort Pulaski.

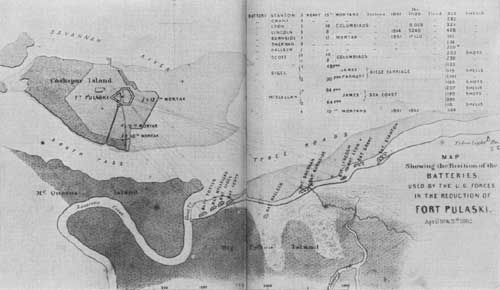

At this time Gen. Robert E. Lee visited Savannah and inspected the defenses of the Georgia coast. No doubt he saw the hopelessness of trying to prevent the blockade and the wisdom of permitting the North to dissipate its forces in garrisons along the coastal islands. Soon after the Port Royal engagement, at any rate, orders were given to withdraw all troops from Tybee Island, which lay across the South Channel from Cockspur, and later from all the other outer islands. The Confederacy would depend entirely upon its strong inner line of defense for the protection of Savannah. Because it was believed that Fort Pulaski would be able to hold out for many months against any attack that could be brought against it, Col. Charles H. Olmstead and 385 officers and men were left in the fort.

In February, Union forces landed on Tybee Island and immediately began the work of constructing batteries for the siege. In command of these preparations was Capt. Quincy A. Gilmore, U. S. Engineer Corps, later brevet major general. Huge cannon and mortars, weighing as much as 17,000 pounds, were landed through the surf on the south side of the island; some were dragged 2 miles through mud and sand by manpower to the positions they were to occupy.

The work was done by night; men were not allowed to talk, and signals were given by whistle. Each morning before daylight the batteries under construction were camouflaged. Colonel Olmstead knew that batteries were being erected on Tybee, but he did not know exactly where. Apparently it made little difference, for he had been told by the military experts that Pulaski was safe from land attack.

But the North had a surprise in store for the South and for the world. At Lazaretto, on Tybee Island, the Union engineers had erected two batteries of rifled cannon—a newly invented weapon. The distance from Lazaretto to Pulaski, a full mile, was almost twice as far as the effective breaching range of the most powerful proved guns. The new cannon, however, firing a conical pointed shell, were destined to do damage at almost unbelievable distances.

April 10, 1862, was a fine spring morning. The marshes around Pulaski were growing green; a few sea gulls were flying about; white herons were feeding on the mud flats. The sun had just come up when the sentry on the parapet of the fort observed a small boat putting out from the shore at Lazaretto under a flag of truce.

In the boat was a young Union officer, Lt. J. H. Wilson. He brought a communication from Maj. Gen. David Hunter to Colonel Olmstead, demanding the surrender of the fort.

To this Colonel Olmstead replied:

"Sir, I have to acknowledge receipt of your communication of this date, demanding the unconditional surrender of Fort Pulaski.

"In reply I can only say, that I am here to defend the Fort, not to surrender it."

Lieutenant Wilson returned to Lazaretto, and at 10 minutes past 8 o'clock the bombardment began. The first shots were wild, but soon the Union gunners found the range and shells began to strike against the walls of the fort as the batteries on Tybee opened up. There were 11 batteries in all, concentrating the fire of 36 columbiads, mortars, and rifles against Pulaski.

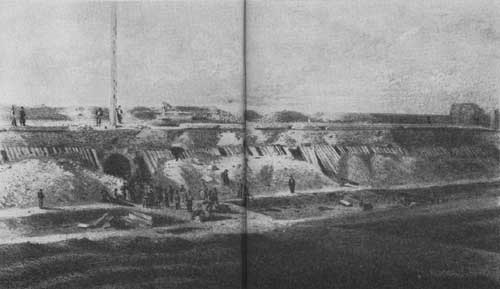

Wartime sketch of Fort Pulaski showing conditions and preparations for the bombardment in April 1862. The trenches across the parade ground were intended to stop the progress of cannonballs landing inside the fort. |

The Federal batteries on Tybee Island directed a converging fire on Fort Pulaski, a mile distant; the rifled cannon in the batteries at the mouth of Lazaretto Creek breached the walls in 24 hours. |

The fort answered with a well-directed fire against the sand dunes of Tybee, the only target visible. Only 20 of the guns in the fort could be brought to bear on the enemy, and about half of these were in casemates on the lower level and could not get sufficient elevation to reach the Union batteries. The defenders of the fort served the guns on the parapet with shells whistling and bursting around them until most of the guns were shot from their platforms. The cannonading could be heard distinctly in Savannah and the shells could be seen bursting in the air.

By nightfall the southeastern angle of the fort was badly shattered. The whole wall from the crest of the parapet to the moat was flaked away to a depth of from 2 to 4 feet. The shells from the rifled cannon were making a honeycomb of the fort, and the heavy, solid-shot columbiad shells were beating down the weakened walls. During the night the Union batteries kept up an occasional fire, while the men in the fort repaired their damaged guns.

At 6 o'clock on the morning of April 11, the fight was renewed. Very soon three holes appeared in the southeastern wall of Pulaski. The impregnable fortress had been breached.

Now a new danger appeared: the huge projectiles were passing through the breach and were striking directly against the brick wall of the powder magazine, in which 40,000 pounds of powder and prepared shells were stored. In an hour or two the magazine would blow up, and even if all the men were not killed the whole northwestern end of the fort. would be destroyed. The breach in the southeastern face was now large enough to permit entrance of a column of eight men abreast. The 8,000 men on Tybee would soon be able to carry out their orders to assault the fort.

It must have been a bad moment for Colonel Olmstead, who was only 25 years old. The situation was absolutely hopeless. Should he continue to defend the fort and thereby gain personal glory that would cost the lives of nearly all of his 385 men? Or should he surrender and save his men? He consulted his officers. At 2 o'clock, 30 hours after the bombardment began, the Confederate flag was slowly hauled down and the white flag run up. All firing ceased immediately. The surrender was unconditional.

From the terreplein, a guide points out to visitors the position of the Federal batteries on Tybee island. The service of free guides is available to all visitors. |

THE SIGNIFICANCE OF THE SIEGE

As one phase of the story of the War between the States, the reduction of Fort Pulaski is important. The blockade directed against the South was materially strengthened by the acquisition of this fortress in the mouth of the Savannah River. After the surrender, Northern troops occupied the fort and commanded the entrance to the principal port of Georgia. It thus served as one of the many pincers that throttled the economic life of the South.

But when viewed in larger perspective an even greater significance may be attached to the battle for the once great fort. There are many incidents in the past that seem to be crucial points in American history. The well-publicized story of the struggle between the Monitor and the Merrimac has long been viewed as a turning point. No less important, however, was the struggle between the two forces at Fort Pulaski, for at that point was demonstrated the total ineffectiveness of a first-line masonry fortress against a new weapon of war—the rifled cannon. The strategy that had guided military experts had to be revised to meet the new threat. Fort Pulaski, because of the consequent change in tactics, has become an interesting relic of another age.

This view, through one of the arches, shows a portion of the 2-1/2-acre parade ground and the gorge, where the officers and men were billeted at Fort Pulaski. |

FORT PULASKI, 1865-1933

WITH the return of peace in 1865 Fort Pulaski was used for a time as a political prison, and among the distinguished leaders of the Confederacy there incarcerated were George Trenholm, Secretary of the Treasury; James A. Seddon, Secretary of War; and Robert M. T. Hunter, Secretary of State.

By 1885, Fort Pulaski had been abandoned as an active post. As a measure for coastal defense during the Spanish-American War a concrete and earthen fort, Battery Hambright, mounting two guns, was built on the island about a quarter of a mile north of deserted Fort Pulaski. Additional defense preparations were made, including the mining of the entrance to the Savannah River and the construction immediately in the rear of Fort Pulaski of a large earth mound as a control chamber. The Spanish fleet never reached American waters, so there was no occasion to use the Cockspur Island defenses against an enemy.

The war scare over, Fort Pulaski and Cockspur Island were totally abandoned. The moat around the fort and demilune completely filled with silt from the river; the tides swept over the neglected dikes and flooded the low-lying marshes; the parade ground of the abandoned fort became a veritable jungle, and hundreds of snakes made their homes there and in the innumerable crevices in the fort's masonry. Infrequent parties of zealous hunters and hardy curiosity seekers, willing to wade through soft marsh, were the only visitors. This desolate condition remained until 1933, when the National Park Service undertook the development of the area.

Rescued from oblivion, Fort Pulaski today tells a story that is a relatively short one in the long American saga, but as a vivid reminder of past events and deeds, it presents an important phase of our great national heritage.

Before

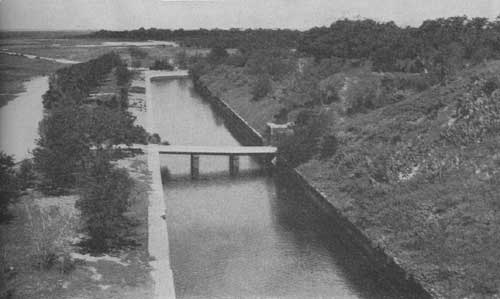

The demilune moat at Fort Pulaski before restoration. |

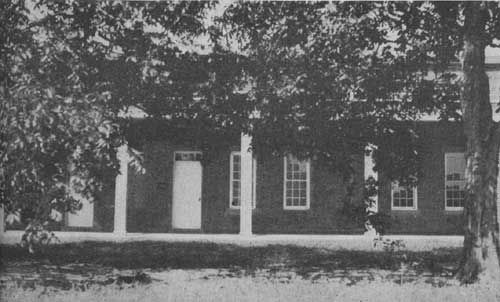

The officers' quarters before restoration. |

After

The demilune moat after restoration. |

The officers' quarters after restoration. |

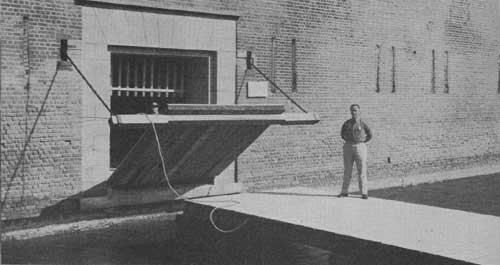

The drawbridge and portcullis, protecting the only entrance to the fort, duplicate the original. |

Fort Pulaski National Monument Today

RESTORATION POLICY AND MUSEUM AT FORT PULASKI

THE PLAN adopted by the National Park Service in the restoration of Fort Pulaski was not to reproduce any one definite period in the history of the fortification, but rather to protect the fort structure from further deterioration by making essential repairs, and to restore only where necessary to illustrate the use and history of certain features of the fort. Original plans and specifications were available in the files of the War Department for practically all items of restoration and repair work undertaken.

Fort Pulaski itself is a large-scale outdoor exhibit. The fort as a whole—the structure together with outlying works, including demilune, drawbridge, ditches, and dikes—should be considered an example of past military architecture, representing a very high development in brick masonry fortification construction. Exhibits in two of the barrack rooms will provide historical continuity and illustrate certain details not readily discernible on a tour of the monument. In a third barrack room will be shown a collection of nineteenth-century bottles and other relics, which were found during the restoration of the fort.

BIRDLIFE AND FOLIAGE

Cockspur and McQueens Islands, which now comprise Fort Pulaski National Monument, are havens for a large variety of land and marine birds. In the spring and summer months the wooded hammocks of Cockspur Island are gay with painted buntings, cardinals, and tanagers. Mockingbirds fill the air with song, the eastern willet cries shrilly, and the marshes resound with the cackle of the clapper rail. Black skimmers cleave the surface of the river with their red beaks in quest of food, while snowy egrets and timid oyster catchers stand guard along the shores.

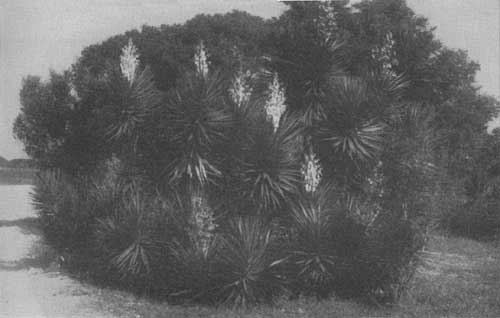

Cockspur Island is dominated by subtropical foliage. Palmetto palms, sweet myrtle, cassena, prickly ash, yucca, and prickly pear cover the hammocks in lush profusion. And from the ramparts of the fort one may look down on tidal marshes extending to the horizon like a vast mosaic in purples, browns, and greens. The prickly pear blooms in May and is covered with purple fruit in autumn and winter. In June the several varieties of yucca unfurl their snowy plumes; while at the Christmas season the ilex cassena and ilex vomitoria are brilliant with bloodred and scarletberries.

The yucca, or Spanish bayonet, blooms during the summer months. |

A snowy egret, two Louisiana herons, and a little blue heron feed at a rainwater pool. |

FORT PULASKI NATIONAL MONUMENT AND VICINITY (click on image for a PDF version) |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> |

1940/fopu/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 20-Jun-2010