|

Fort Union

Historic Resource Study |

|

CHAPTER THREE:

MILITARY OPERATIONS BEFORE THE CIVIL WAR

The primary mission of the army in the Southwest was to keep the peace and, in the event it became necessary, to make war. Essentially, then, in New Mexico the soldiers provided protection for settlers and travelers from Indian raiders. Troops stationed at Fort Union were engaged in such military operations during much of the history of the post. One consideration in the selection of the location for Fort Union in 1851 was its proximity to the main route of the Santa Fe Trail (which in 1851 and after was sometimes referred to as the "Cimarron Route"), the Bent's Fort Trail (also known as the Raton Route and, much later, called the Mountain Route of the Santa Fe Trail), [1] and the frontier settlements. The line of communication and supply with the eastern states was vital to the army and the developing economy of New Mexico Territory and, of all the military posts established in the Southwest, Fort Union was the one most responsible for protecting the mails, government supply trains, and merchant caravans traversing the plains. Special escorts were provided for government officials traveling to and from New Mexico Territory. Troops from Fort Union were sent with military expeditions throughout the region, and they were called upon especially when Indian troubles threatened in the area close to the post. [2]

The success or failure of these military operations provided the grounds by which the larger public judged the contributions of the army to the safety and development of the Southwest. Only military personnel understood that routine garrison duties, construction and maintenance efforts, procurement and distribution of supplies, dietary provisions and health care, all those details which took most of the soldiers' time and about which the general public understood little, were indispensable prerequisites for military operations to occur. Field service required little time of any particular soldier, in comparison with other responsibilities, but it was the ultimate purpose of his presence in the Southwest and at Fort Union.

|

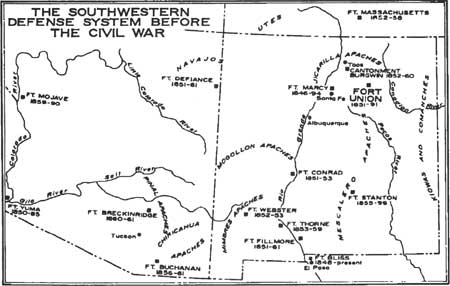

| Southwestern Defense System before the Civil War. Source: Robert M. Utley, Fort Union National Monument, 34. |

Until the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861 the primary objective of military operations focused on Indians—prevention of attacks and raids if possible (scouts, patrols, escorts, and sometimes reconnaissance parties and exploring expeditions) and the pursuit and punishment of parties guilty or presumed guilty of hostile activities (search-and-recovery or search-and-destroy missions, campaigns against specific marauding parties or members of a particular tribe in general, and expeditions into selected areas designed to force Indians to stop raiding, sign peace agreements, and/or relocate to a specified reserve). Occasionally the military was called upon to help enforce civil law and order in the territory. Whatever was required to keep the peace the army was expected to do. The soldiers who served at Fort Union, like soldiers everywhere, were usually evaluated in the short-term by how effectively they made war, but in the long-term it was even more important how effectively they kept the peace. It was relatively easy to determine success or failure in warfare, but it was virtually impossible to determine the potency of the army in preventing conflicts. The military, an agency of the Anglo-American penetration of New Mexico, was only one of several parties in the complex and fragile structure of ethnic intercourse in the region.

Indian-white relations were difficult on every American frontier during the nineteenth century but especially so in the Southwest because of two and a half centuries of Hispanic Indian associations prior to annexation of the region by the United States. Although Hispanics and Indians had frequently destroyed life and property in their conflicts, they had developed a system of mutual survival in a harsh environment. The infusion of Anglos disrupted those patterns, and the Indians eventually found the survival of themselves and their cultures threatened. Diseases to which Indians had little if any resistance decimated their numbers, while Anglo settlers wanted to obtain title to the land. Indians and Hispanics felt the heavy hand of Anglo domination, the "Americanization" of their societies. [3]

Indian-white relations were complicated by a number of factors, the most important being that few if any members of one society understood the culture of the others. It was difficult, perhaps impossible, for most people to transcend their cultural heritage and values, resulting in the tragedy of what ethnohistorian Calvin Martin called "mutual incomprehension." [4] The three cultural groups in the Southwest had different concepts of family life, personal values, social relations, religion, uses and ownership of land and other property, how best to obtain the provisions of life, and warfare.

Anglo-American thinking was dominated by ideas of ethnocentric superiority, private property in land, a market economy, individual opportunity, democracy, Protestant Christianity, and especially the idea of progress (usually conceived as economic development). Indians stood in the way of progress and, by Anglo standards, they were also in need of it. Indian culture was considered by Anglos to be substandard or deficient in civilization, but that could be improved if not cured by adapting Anglo institutions and values, particularly the English language, Christianity, private property in land, and anything else that would cause them to cease being Indians and be more like Anglos. The central issue of conflict between Indians and Anglo-Americans was land—the Indians had it and Anglos wanted it—and there lay the essence of the struggle. The non-Pueblo Indians were considered to be the major obstacle to the Anglo exploitation and development of New Mexico. [5]

Indian cultures especially experienced new pressures and threats to their traditional ways after the Mexican War, and Indian leaders considered how to react. The complexities of the problem were expressed by literary scholar Richard Slotkin: "The Indian perceived and alternately envied and feared the sophistication of the white man's religion, customs, and technology, which seemed at times a threat and at times the logical development of the principles of his own society and religion. Each culture viewed the other with mixed feelings of attraction and repulsion, sympathy and antipathy." [6] Indian resistance in New Mexico became more determined after the Anglo invasion because their ways of life and their land bases were threatened. Some Indian leaders feared resistance would lead only to destruction of their culture and hoped to survive and preserve some of their traditions by accommodating to Anglo desires. Over time acculturation resulted as all three cultures influenced the others, including changes in values, attitudes, institutions, and material culture. The most obvious and far-reaching changes were experienced by Indians who eventually lost much of their traditional culture or preserved it subrosa while appearing to become more like Anglos. Indians became dependent on trade with whites, but some commodities supplied, such as guns and alcohol, contributed to the difficulty of keeping the peace. Fewer changes affected the Hispanics, but many of them also lost their land and absorbed some Indian and Anglo characteristics. The Anglo culture experienced the least change as it became dominant during the last half of the nineteenth century but was also influenced by the other cultures.

The Indian policies of the United States were not constant because of changes from one presidential administration to another, the willingness or unwillingness of Congress to approve treaties and pass appropriations bills, [7] and the division of authority over Indian relations between the War Department and the Department of the Interior. The Bureau of Indian Affairs was established as a part of the War Department in 1824 but was transferred to the newly-organized Department of the Interior in 1849. The Bureau of Indian Affairs was primarily responsible for obtaining land title from Indians and administering the affairs of the Indians after they surrendered their lands. In each territory there was a superintendent of Indian affairs, usually the territorial governor. Indian agents were appointed to deal directly with specific tribes or bands of tribes and to administer Indian reservations when established.

The army was responsible for maintaining the peace, protecting settlements from Indians, safeguarding Indians from illegal encroachments on their lands, punishing Indians who were hostile, bringing recalcitrant Indian leaders and bands to the negotiating table, and rounding up Indians who left the reservation. The lines of authority between the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the army were not clearly drawn. The officials of the war and interior departments often failed to cooperate, leaving Indians confused and victims of conflicting demands and promises. Besides Bureau of Indian Affairs officials and the army, other parties influenced Indian-white relations, including licensed and unlicensed Indian traders (Pueblo, Hispanic, and Anglo), hunters who entered traditional Indian hunting lands, missionaries of varying religious persuasions, merchants who benefited from unsettled conditions, settlers who lost (or claimed to have lost) property to Indian raiders, and politicians who saw Indian problems as issues to be exploited for election purposes. By benefit of hindsight the outcome of Indian-white relations was virtually inevitable because of the tremendous disparities of population, resources, technology, and resistance to diseases, but the outcome of the so-called "Indian problem" in the Southwest was not decided until the 1880s. Troops and supply trains from Fort Union were directly involved in the events which yielded that conclusion.

During the 1850s, despite the signing of many treaties by leaders of tribes in New Mexico (which were, as noted, not approved by the Senate nor funded by Congress), the army was expected to keep the peace and punish offenders. As historian Robert Utley explained,

the history of Indian relations in New Mexico during the 1850s is largely a military history. Even consistent, well-financed civil policies could not have overcome the patterns in which generations of hostility had locked both Indians and colonists—patterns of raid and counterraid, of plunder and pillage, and of enslavement of captives by both sides. From the little forts . . . the troops campaigned against the elusive foe. [8]

As soon as Colonel Edwin Vose Sumner established Fort Union, he directed troops there and throughout New Mexico to participate in military operations against Indians. He arranged for better protection of the Santa Fe Trail and continued preparations for the campaign against the Navajos. On August 2, 1851, in the same order naming Fort Union, Sumner directed that "in order to afford protection to travel and commerce between the Missouri frontier and this territory, Major Carleton's Company K 1st Dragoons, will be kept in motion this summer and fall along the Cimarron route, between this place and the post below the crossing of the Arkansas river [Fort Atkinson], returning finally to this post." [9] The primary mission of these patrols was protection of the stagecoaches and mail they carried, giving some protection directly or indirectly to other travelers and freight caravans on the trail.

Later, when the possibility of Indian attacks on the mail coaches threatened, the patrols were replaced with escorts which accompanied the eastbound mails from Fort Union to the Arkansas River in Kansas Territory and the westbound coaches (if connections were made) from the Arkansas River to Fort Union. Sometimes the escort of approximately 20 soldiers was mounted and rode near the mail wagons or coaches; other times the escort rode in wagons which accompanied the mails. Only rarely were these armed patrols or escorts attacked by Indians. Beginning with Carleton's first patrol in 1851, military commanders considered these efforts successful in protecting the Santa Fe Trail.

Carleton and his command left Fort Union on August 3, 1851, and followed the Cimarron Route to Fort Atkinson on the Arkansas River, where a mail station had been established. He was instructed to move slowly along the Santa Fe Trail, remain at Fort Atkinson for one week, and return at a leisurely pace over the same route. He was to watch for Indians along the way, show "great kindness" to those who were peaceable, and promptly punish any who were considered hostile. After recuperating at Fort Union for approximately 10 days after making the first trip, the same troops were to make a second patrol under the same directions. [10]

Sumner reported several weeks later, "that no depredations, whatever, have been committed on the road to Missouri, since Major Carleton has been upon it." [11] This system of patrols operated until November 4, 1851, when Carleton's command returned to Fort Union for the winter months, and was repeated during part of the following summer. Later, when escorts replaced patrols, the troops from Fort Union operated in conjunction with Fort Atkinson until that post was abandoned for the last time in October 1854. [12] After Fort Larned was established in Kansas Territory in 1859, a system of escorts was coordinated between that post and Fort Union. In this way, one of the missions of the Fort Union garrison, protection for the Santa Fe Trail, was achieved.

The Santa Fe Trail may have been clear of Indian raids in the summer of 1851, but much of the Territory of New Mexico was without adequate protection. Sumner led a large force against the Navajos on August 17 and established Fort Defiance near their homeland on September 18, but members of that tribe slipped around those troops in the field and raided unprotected settlements near the Rio Grande Valley. [13] Before Sumner returned from the Navajo campaign, which failed to engage the enemy, additional attacks were made on New Mexican settlements. [14] In the fall of 1851 Indian Agent John Greiner reported from Taos that some of the Utes and Jicarillas were bragging about their raids and how many settlers they had killed. [15]

After Sumner returned to Fort Union, New Mexico Governor James S. Calhoun, in response to citizen requests, asked Sumner to authorize the issue of military arms for a volunteer militia unit in the territory so the people could better protect themselves from destruction at the hands of Indians. After some delay, Sumner authorized Captain Shoemaker to issue 75 flintlock muskets, with ammunition and necessary accouterments, to the governor for the use of a militia unit to be led by Captain Preston Beck. [16] Sumner placed two restrictions on the "loan" of arms; one, that they would "be immediately returned whenever demanded by the Commanding Officer of the 9th Dept., and secondly that they are never to be used in making hostile incursions into the Indian Country unless this volunteer company is acting in conjunction with the regular troops." [17] These restrictions were unacceptable to Captain Beck, and the arms were refused. [18] A period of strained relations between Sumner and Calhoun followed. [19] When Governor Calhoun became too ill to perform the duties of his office, he appointed Indian Agent Greiner to act as superintendent of Indian affairs in the territory. Greiner and Sumner were unable to cooperate either. [20] Despite those problems, however, the Indians of the territory were reported to be quiet early in 1852.

Colonel Sumner was satisfied that the new posts he had established closer to the Indians' homelands were having a "favourable influence" on relations between citizens and Indians. In late January 1852 he declared that the Jicarilla Apaches and the Utes "have been perfectly quiet" because of the presence of Fort Union. When Fort Massachusetts was established some 80 miles north of Taos in the heart of Ute country the following spring, he believed that the presence of troops would ensure "their permanent submission." [21]

Sumner hoped to have a similar impact on the Mescalero Apaches to the south of Fort Union. On February 3, 1852, Captain Carleton and his Company K, First Dragoons, total of 61 men, departed Fort Union on a reconnaissance to Bosque Redondo on the Pecos River, with a stop at Anton Chico to pick up forage for the horses. The corn purchased there was still on the ear, and the soldiers spent much of their time for a few days shelling the corn by hand to make it easier to transport. As they marched to the Bosque Redondo, they cached some of the corn to provide forage for their horses on the return trip. Carleton reported there was little grass along the way. On the return march, the troops found that one place where they had cached corn had been found by "Mexican" hunters who had taken the entire amount. [22]

Carleton's company was to watch for Indians, particularly Mescalero Apaches, and try to impress upon them the "necessity" for peaceful behavior. [23] They saw no Indians during the entire trip but learned from "Mexicans" that Apaches, Comanches, and Kiowas gathered at Bosque Redondo in the spring to recruit their ponies and carry on a lively trade among themselves and with "Mexican" buffalo hunters. Carleton was impressed with the region, especially the Bosque Redondo. He described at length the lay of the land along the Pecos River, the rich bottom lands at and below the Bosque Redondo with potential for successful agriculture, an abundance of trees, grass, sunflowers, wild grapes, and large flocks of wild turkeys. Carleton saw it as an ideal location for a military post, especially for a cavalry garrison. The presence of troops in that area, he predicted, would be quickly followed by "Mexican" settlers who would develop the potential of the land. [24] Carleton returned to Fort Union on February 24 with a total command of fifty-seven, four less than he started with three weeks earlier. He reported that three men had deserted and one, Private Patrick O'Brien, had died. [25]

In March 1852, following reports of raids by Gila Apaches at San Antonio on the Rio Grande between Valverde and Soccoro, where two New Mexicans were killed and livestock was stolen, Governor Calhoun requested 100 muskets and ammunition from Sumner to issue to a militia unit at San Antonio. Sumner directed Captain Horace Brooks, Second Artillery, commanding Fort Marcy at Santa Fe, to turn over the requested weapons, 5,000 cap and ball cartridges, and 300 flints to the governor to be used by citizens at San Antonio led by Estanislas Montoya. Calhoun asked Brooks to deliver the items to San Antonio. Brooks was unable to fulfill the order because he did not have the muskets at Santa Fe, and he informed Calhoun that he did not have available transportation to deliver the weapons if he had them. Calhoun, so ill that he was unable to fulfill his duties, appealed to Sumner, who ordered Brooks to obtain the necessary arms and ammunition from Captain Shoemaker at the ordnance depot at Fort Union. [26]

With the coming of spring, troops at Fort Union and throughout the department renewed their efforts to control the Indians. On April 3, 1852, Second Lieutenant Joseph Edward Maxwell and his Company D, Third Infantry, were ordered from their station at Fort Union to department headquarters at Albuquerque for "field service against the Apache Indians." The quartermaster at Fort Union was required to "furnish the necessary transportation for the movement" of the company. [27] On April 20, Carleton and his company of dragoons were directed to leave Fort Union to patrol the Santa Fe Trail to Fort Atkinson on the Arkansas River. They were to remain at the destination for a few days to rest and "recruit" the horses, then march back to Fort Union. [28] Because of other Indian troubles in the department and the shortage of troops at Fort Union, it appears that this order was not carried out. Carleton assumed command of Fort Union on April 22, 1852, and his company was present for duty there until August 3. In August Carleton and his company of dragoons patrolled the trail as far as Fort Atkinson and escorted the new territorial governor from that point back to Fort Union. [29] In October 1852 an escort was provided from the garrison at Fort Union to accompany Major Francis A. Cunningham, paymaster, and Major and Mrs. Philip R. Thompson as far as Fort Atkinson. [30]

During April 1852 two companies of First Dragoons and one company of Third Infantry, under command of Major George Alexander Hamilton Blake, First Dragoons, were sent to establish Fort Massachusetts "in the country of the Utah Indians." [31] The new post was located on Ute Creek, a tributary of the Rio Grande, near the San Luis Valley on June 22, 1852. It was occupied until June 24, 1858, when the garrison was moved to a nearby site and Fort Garland was established. [32]

While troops were marching to establish Fort Massachusetts in the spring of 1852, a council was held with some Jicarilla leaders at Pecos, followed by further discussions in July. [33] There were no reported attacks by Jicarillas on the New Mexican settlements during the year, but in August a Jicarilla war party went onto the plains to fight the Kiowas. The Kiowas had, according to two Jicarillas met by soldiers at Ocate, recently killed three or four Jicarillas. [34] Although the Indians were peaceful, military protection continued.

The provision of military escorts by troops at Fort Union for departing Governor Calhoun and the coming of Governor William Carr Lane in 1852, also part of military operations, were covered in the previous chapter. [35] For whatever reasons, including Sumner's redistribution of the troops in the department and efforts by Bureau of Indian Affairs officials to negotiate treaties of peace with tribes in New Mexico, a brief period of unprecedented peace was experienced in the department in 1852. Greiner declared at the end of June 1852, "Not a single depredation has been committed by any of the Indians in New Mexico for three months. The 'oldest inhabitant' cannot recollect the time when this could have been said with truth before." [36] Colonel Sumner reported in September that "all things continue quiet in this department" and attributed this to his reorganization of the department. [37] It appeared to military and civil officials that opportunities existed to negotiate peace treaties and make arrangements to locate the Indians on their own reservations, providing them help with subsistence provisions while they made the transition from hunters and raiders to farmers and ranchers.

Governor Lane, new territorial governor and superintendent of Indian affairs, became a strong advocate of peace. Perhaps persuaded by Greiner, Lane concluded that it was more economical to feed Indians than to fight them. He proceeded, without approval of higher authority, to negotiate treaties with several New Mexican tribes, including the Jicarilla Apaches. He promised to feed the Indians for five years and give additional aid if they would stop raiding, settle in a specified location, and take up agriculture. He spent, without authorization, between $20,000 and $40,000 to implement the agreements, and several hundred Indians were reported to be settled on potential reservations. When the Senate rejected the treaties and Congress refused to fund the expenses incurred, the distribution of rations had to be stopped and the Indians felt betrayed. All crops planted by the Indians in 1853 failed. They began to raid in order to survive and in retaliation for the broken promises. Lane was criticized for his actions and resigned from office. [38]

During the interim when one governor left office and another arrived, Colonel Sumner was replaced by Brigadier General John Garland as department commander. Before he left New Mexico, Sumner directed preparations for a campaign against the Navajos which included most of the troops at Fort Union (all the artillery and dragoon companies stationed there plus most of the company of infantry). The dragoons were directed to lead their horses until they reached the heart of Navajo country, so the animals would be in good condition for battle. As noted in the previous chapter, the campaign was never conducted because the issue with the Navajos was resolved by the troops at Fort Defiance. [39]

If Carleton and his company of dragoons had gone on the planned expedition, they might not have experienced an Indian raid on their horse herd. On July 29 the dragoon horses were grazing in a cañon in the Turkey Mountains about five miles northeast of Fort Union when five Utes attempted to stampede the herd but succeeded in stealing only one horse. Carleton and a detachment of his company followed the trail for four days before losing it in the mountains. The horse was not recovered. The leader of the Ute party was understood to be Chief Tamooche. Carleton was furious that this had happened near the post and under the watch of troops and exclaimed, "Had I caught or killed these Indians, dead or alive I should have hung them upon the trees at the point where they stampeded the horses." [40]

Governor David Meriwether arrived to replace Lane in August 1853, and he, like Lane, wanted to feed the Indians in order to keep the peace. Meriwether, like his predecessor, was unable to secure funds to do so. The Indians continued to raid in order to survive, and Meriwether called for additional military support to protect the settlements. In September 1853 a party of Jicarillas came to Fort Union, ostensibly to trade, and remained most of the month. They were apparently checking on the strength of the command, and they suddenly left and were raiding in the area a few weeks later. Late in the year Jicarillas killed a rancher, Juan Silva, and his son near Las Vegas and stole his herd of cattle. A detachment of dragoons was sent from Fort Union but was unable to find the Indians or the stolen cattle. [41]

Governor Meriwether notified Brigadier General Garland in January that Indian disturbances in the northern part of the territory were increasing and requested additional military vigilance in the area. Garland sent orders to Lieutenant Colonel Cooke and Major Blake, the commanding officers at Fort Union and Cantonment Burgwin, to investigate all reports of Indian depredations and to punish the delinquents. Garland was of the opinion that the primary cause of heightened Indian troubles was attributable to "large armed parties of New Mexicans" who "are in the habit of going into the Indian Country, or perhaps more properly speaking, their hunting grounds, where they kill off the very game upon which the Indians depend for subsistence." This left the Indians in the desperate situation of either "starving to death" or "depredating upon the settlements." [42]

That New Mexican hunters were contributing to the Indian problems in the territory was confirmed by an investigation of the circumstances surrounding the reported loss of property by a party of hunters from San Miguel. The hunters informed Governor Meriwether, who in turn notified Garland, that Indians had attacked their camp on the Canadian River, killed one of the hunters, stolen some of their property, and prevented the survivors from recovering their wagons and other supplies at the camp. Garland directed Lieutenant Colonel Cooke at Fort Union to send troops to investigate and escort the hunters to their wagons and assist in the recovery of their property, punishing any Indians found along the way. In addition Cooke was to examine the reported murder of two Anglo men near Las Vegas, possibly by Indians. The inquiry gathered evidence quite contradictory to the initial reports. [43]

Cooke, who wondered why the hunters had not informed him of their losses, sent Lieutenant Joseph E. Maxwell and a detachment troops from Fort Union to gather information and assist the men from San Miguel in the recovery of their carretas and other property. Cooke observed, before the facts were collected, that the hunters "were probably intruders on indian lands." Maxwell learned that the two men killed near Las Vegas had been the victims of New Mexican thieves rather than Indians, and one of the murderers had been apprehended and then released. He ascertained that the hunting party of Pedro Gonzales of San Miguel had gone far beyond the Canadian River where the Indians had repeatedly warned them to leave, stating that a few hunters were not a problem but many hunters with wagons were not welcome. The hunters claimed that the Indians, believed to be Cheyennes, took some of their horses and later returned them. At a time when Gonzales was not at the camp, several of the hunters killed two Indians and wounded a third who escaped. One of the hunters was killed. The hunting party, fearing revenge by the Indians, had abandoned their camp and were afraid to go back to recover the wagons and supplies. Cooke strongly urged that "these particular hunters be judicially investigated on the charges of murder" and for illegal intrusion on Indian lands. Considering the murder of two men near Las Vegas, the unprovoked killing of two Indians, and the illegal activities of New Mexican hunters, the commander of Fort Union observed, "It would seem that white men and Indians are at present most in need of our protection." [44]

A series of events that led directly to war began in February 1854 when Samuel Watrous, one of the beef contractors for Fort Union, reported the loss of several cattle to Indians. The cattle were herded about 60 miles from Fort Union, apparently along the Canadian River. A party of Jicarillas and Utes were suspected of stealing the animals. Lieutenant David Bell was sent with a detachment of 33 troops of his Company H, Second Dragoons, from Fort Union on February 13, with Watrous's son-in-law William Tipton as guide, to attempt to find and recover the lost stock. They did not find Indians or cattle and returned to Fort Union after one week. [45]

Lieutenant Bell and 35 enlisted men of Company H, Second Dragoons, accompanied by Lieutenant George Sykes, Second Dragoons, and Second Lieutenant Joseph E. Maxwell, Third Infantry, were sent from Fort Union on March 2 to "make a scout" for hostile Indians and stolen livestock on the Canadian River and "to protect the frontier." On March 5 they picked up a trail and followed it to a point near a Jicarilla encampment, about 70 miles from Fort Union beyond the Canadian, where they were met by several mounted Indians. Following an attempt to talk with these Apaches about the stolen cattle, which they denied having anything to do with and suggested the Utes were probably guilty of the theft, Bell accused them of stealing the cattle and demanded that the thieves and cattle be delivered to him. The soldiers were directed to take Chief Lobo as a prisoner until the demands were met. [46]

Lobo resisted and a brief skirmish followed. The Indians fought only a few minutes and then scattered, but Bell did not pursue them because he suspected a possible ambush. The Jicarillas lost five men killed, including Chief Lobo, and several wounded. The soldiers had two killed (Privates William A. Arnold and James Bell) and four wounded (Bugler Adam T. Conalki and Privates Edward Golden, John Steel, and William Walker). An express rider was sent to Fort Union to report, and Post Surgeon John Byrne was dispatched from the post with an ambulance to meet the detachment and attend to the wounded on the way back to the post. They returned to Fort Union on March 7 without further attempts to recover the cattle. The soldiers were especially pleased to have killed Chief Lobo who was considered the leader of the attack on the White party in 1849, the killer of Mrs. White, the leader of the attack on the mail party at Wagon Mound in 1850, and other outrageous acts. [47]

The next day a raiding party of Utes and Jicarillas killed two herders and drove off approximately 200 cattle of the Fort Union depot herd which were being grazed by a contractor within 20 miles of where the fight occurred on March 5. The raiders were prevented from stealing the entire herd by a small band of friendly Utes led by Chief Chico Velasquez, an act which Lieutenant Colonel Cooke called "extraordinary." [48] A platoon of 25 dragoons was sent under Lieutenant Bell on March 9 to recover the stock and punish the guilty Indians but returned a few days later without finding either Indians or cattle. Reinforcements, 60 dragoons under command of Lieutenant Samuel D. Sturgis, were sent to Fort Union from Albuquerque, and Cooke was directed to keep the Santa Fe Trail open, escorting the mails and wagon trains as required. An escort was sent on March 15 to meet the westbound mail and see it safely through the region of recent hostilities. On March 22 Sturgis led a detachment of his company of First Dragoons to the Canadian River to see if any of the missing cattle could be located. The following day Lieutenant Bell left with another detachment to go to the Pecos River on a similar mission. Neither force was successful in locating the Jicarillas, but the dragoons under Lieutenant Sturgis found fourteen of the missing cattle and brought them to Fort Union. [49]

Most of the Jicarillas and Utes were still friendly in early March 1854, and about 45 lodges of peaceful Apaches camped about three miles from Mora. A company of dragoons was sent from Cantonment Burgwin near Taos, at Cooke's request, to keep watch over this camp and prevent them from joining in the hostilities. A New Mexican, who apparently wanted the Indians to leave the area, told these Jicarillas that the troops planned to attack them if they remained there. They left and scattered, some going toward Taos, some toward the Rio Grande, and others to join another peaceful encampment near Picuris Pueblo. Indian Agent Kit Carson, recently appointed to the Taos Agency to deal with the Utes and Jicarillas, was sent to meet with some of the peace leaders. On March 25 he held council with eight Jicarillas, including Chief Chacon, who proclaimed peaceful intentions and asked for protection and provisions if they remained in their camps. Governor Meriwether was on an extended leave of absence, and Carson urged Acting Governor William S. Messervy to send a special agent to live with the peaceful Jicarillas and to provide them with provisions. [50]

Because of the division of authority between the army and the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the peaceful Indians were under control of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the hostiles were under control of the army. It was not always possible, however, to determine who was hostile and who was friendly. The peaceful camp near Picuris was to receive rations so long as they stayed put, but for some reason they fled while Carson was at Santa Fe. They met Major Philip R. Thompson's detachment of dragoons, marching from Fort Union to Cantonment Burgwin, and Thompson asked for four Jicarillas to accompany him as hostages to guarantee that the band remained peaceful. They did as he requested, but the following day the band and the hostages escaped and were no longer counted among the peaceful Indians. [51]

Lieutenant John W. Davidson and a company of dragoons from Cantonment Burgwin were sent to follow the fleeing Jicarillas on March 30. This company was attacked by a force of Jicarillas and Utes (estimated to number from 100 to 250 warriors) near Cieneguilla (present Pilar) about 25 miles south of Taos. The Indians apparently ambushed the soldiers. Messervy declared of the Jicarillas, "the whole plan of their operations was to draw our troops into an ambush, destroy them, and then invite the Utahs to join them in a general massacre of our citizens." [52] In a hard-fought three-hour battle Davidson's troops suffered 22 killed and 36 wounded and lost most of their supplies and 22 horses to the Indians. Lieutenant Davidson and Assistant Surgeon David L. Magruder were among the wounded. [53] All the Jicarillas were now considered at war and the army was given responsibility for punishing them until they sued for peace. [54]

Lt. Davidson's conduct in the tragic engagement, when his troops were attacked by a force of superior numbers, was praised by Brig. Gen. Garland: "The troops displayed a gallantry seldom equalled in this, or any other country and the Officer in Command, Lieut. Davidson, has given evidence of soldiership in the highest degree creditable to him. To have sustained a deadly control of three hours when he was so greatly outnumbered, and to have retired with the fragment of a company, crippled up, is amazing and calls for the admiration of every true soldier." Garland to Thomas, April 1, 1854, Sen. Ex. Doc. No. 1, 33 Cong., 1 sess. (Serial 747), pt. 2, pp. 33-34.

Lt. David Bell later charged that Davidson could have avoided the engagement and had exhibited poor leadership, thereby losing many of his men unnecessarily. Garland was incensed and called a court of inquiry to meet at Taos on March 10, 1856, to consider Bell's charges and to assess Davidson's conduct during the battle. Col. B. L. E. Bonneville and Captains James H. Carleton and William N. Grier were detailed for the court, with Lt. Henry B. Clitz as recorder. Orders No. 1, HQ DNM, Feb. 9, 1856, DNM Orders, v. 36, p. 346, USAC, RG 393, NA.

The court concluded that Davidson could not have avoided the battle (meaning he was attacked and not the instigator of the engagement) and "that in the battle he exhibited skill in his mode of attacking a greatly superior force of hostile Indians; and prudence, and coolness, and courage, throughout a protracted engagement; and finally, when he was obliged to retire from the field, owing to the great odds opposing him, the losses he had sustained, and the scarcity of ammunition; his exertions to bring off the wounded men merit high praise." Garland approved the findings and observed that Bell's "accusations present the appearance of malicious criticism." Orders No. 3, HQ DNM, Mar. 26, 1856, ibid., 348-349.

Kit Carson later testified to Davidson's bravery: "Nearly every person engaged in, and who survived that day's bloody battle, has since told me that his commanding officer never once sought shelter, but stood manfully exposed to the aim of the Indians, encouraging his men, and apparently unmindful of his own life. In the retreat, he was as cool and collected as if under the guns of his fort. The only anxiety he exhibited was for the safety of his remaining men." Quoted in James F. Meline, Two Thousand Miles on Horseback, Santa Fe and Back: A Summer Tour (1866; reprint, Albuquerque: Horn & Wallace, Publishers, 1966), 104.

Lieutenant Colonel Cooke left the command of Fort Union to Captain Nathaniel C. Macrae and took charge of a campaign against the Jicarillas. His force included Company H, First Dragoons, Company H, Second Dragoons, and Company D, Second Artillery, from Fort Union, with additional troops from Cantonment Burgwin. A Spy Company recruited among civilians around Taos (including many Pueblo Indians), led by Captain James H. Quinn, served as guides and scouts to pursue the Jicarillas. Indian Agent Carson also accompanied Cooke. On April 7 Garland sent word to Cooke that the leader of the Jicarillas who had attacked Lieutenant Davidson's command, Flechas Rayada, had offered to return all the horses and arms captured in that fight if peace could be made. Garland was opposed to negotiations. Carson later declared that he thought the Jicarillas around Taos "were driven into the war, by the actions of the officers & troops in that quarter." He believed that, "thinking there will be no quarter or mercy shown them, they will resort to all desperate expedients to escape any sort of pursuit & they have scattered now in every direction." He urged that peace negotiations be attempted. [55]

The Jicarillas fled westward across the Rio Grande, and Cooke started after them from Taos on April 4, 1854. The troops carried rations for 30 days, including beef and mutton on the hoof. Brigadier General Garland enjoined Cooke to "listen to no proposition for peace until these marauding Apaches have been well whipped, give them neither rest nor quarter until they are humbled to the dust." Jicarillas and soldiers struggled through rugged terrain and spring blizzards. On April 8 the troops came upon a Jicarilla camp, believed to include Chief Chacon and more than 150 of his followers, beside the Rio Caliente, tributary of the Chama River, and attacked. The Indians were driven from their camp which the soldiers destroyed. Some Jicarilla women and children (one source said "a large number of their children") and at least two of the Indians' horses drowned while trying to cross the stream. It was later learned that four or five Jicarillas were killed and five or six were wounded in the attack. The soldiers lost one killed and one wounded. Because of the loss of their camp and supplies, the Indians suffered from exposure and seventeen women and children perished in the snow. Although Chief Chacon had professed for peace and claimed he and his followers had participated in no raids or attacks, he and his band were the ones overtaken and punished in retaliation for the earlier raids and the attack on Lieutenant Davidson's command. [56]

A portion of Cooke's command, Captain William T. H. Brooks and a company of Third Infantry, tried to overtake Chacon's band which fled farther into the mountains, while Cooke continued the search for other bands with the remainder of the troops. Both commands ran into deep snow which forced them to abandon the chase and return to Taos. Cooke and the dragoons from Fort Union returned to that post in May. On May 23, following reports of Jicarillas moving into the Sangre de Cristo Mountains north of Taos, Cooke sent Captain James H. Carleton with one hundred men, including the Spy Company and Carson, in pursuit. They followed the trail across the mountains to the plains. On May 31 a grizzly bear "tore one of the Pueblo spies badly." The bear was killed. The Indian trail led them to Raton Pass. They climbed Fischer's Peak near the north end of the pass on June 4 and surprised a camp of 20 Jicarilla lodges on the mesa, under Chief Huero. The Jicarillas, whom Carleton described as "panic-stricken," escaped but lost their entire camp which was destroyed and 38 horses which were captured and given to the Spy Company. A few soldiers and spies remained near the camp when the main body of troops left and killed a few Jicarillas when they came back to see what remained of their camp. No other Indians were found on the march back to Taos. [57]

During May Acting Governor Messervy called into service for three months a battalion of militia to include 200 volunteers. These were stationed in northeastern New Mexico to protect the settlements "from the invasion of the Indians." In addition to the hostilities of the Jicarillas, the Kiowas, Comanches, and Cheyennes were reported to be raiding in San Miguel County where fourteen New Mexicans were killed. Lieutenant Colonel Cooke, back at Fort Union, declared that the attacks by the plains tribes "is reasonably to be expected & in retaliation of serious depredations committed by the Inhabitants of the territory on them: viz, the annual destruction of buffalo within their country." Garland attributed the murders in San Miguel County to the unprovoked killing of plains Indians by buffalo hunters the previous winter. "These Indians," he wrote, "as is their custom took their revenge." [58]

Troops from Fort Union continued to investigate reports of Indian raids. On May 20 Second Lieutenant Robert Ransom, First Dragoons, led 96 dragoons from the post to pursue and punish Indians reported to be killing herders and stealing sheep between the Pecos and Canadian rivers. They went via Las Vegas to Alexander Hatch's Ranch on the Gallinas River, where they were informed that the Indians had attacked the herders and taken the sheep of Juan Perea, located about 40 miles east of Hatch's Ranch. Leaving the pack train in camp with a guard, Ransom took the remainder of his detachment to the scene of the raid. They found about 3,000 sheep without herders and drove them back to the settlements to be claimed by their owners. Because of recent rains, they found no sign of Indians. When they returned to the Gallinas with the sheep, the soldiers met some herders with the remainder of Perea's sheep. They claimed that Indians had stolen 6,500 of their sheep and killed one herder. [59]

It was possible the Indians had driven the sheep toward the Pecos or Canadian River. Ransom picked up the pack train and headed down the Pecos in search of Indians. On May 25 his command overtook a small party of Indians, believed to be Mescalero Apaches, with a herd of stolen cattle and gave chase for about four hours. The Indians killed many of the cattle and fled. Ransom was forced to abandon pursuit when the dragoon horses became exhausted. He reported that the Indians had "scattered, no two taking the same trail; throwing away every article that would at all retard their flight." The next day the detachment went beyond Bosque Redondo and found no Indians. They then headed toward the Canadian River, hoping to find the sheep stolen from Perea. They found a trail of a large flock of sheep and the carcasses of many sheep that had been killed, but they were unable to overtake the Indians. Ransom blamed the poor condition of the horses for the failure to catch Indians. The troops recovered about 2,000 sheep that the Indians had abandoned and drove them to Las Vegas where they could be claimed by the owners. The identity of the Indians who stole the sheep was unknown, but Ransom thought they were from the plains. The detachment returned to Fort Union on June 3. [60]

On June 30 fifty-eight men of Companies D and H, Second Dragoons, from Fort Union, under command of Lieutenant Sykes and Second Lieutenant Maxwell, both Third Infantry, who had been joined in the field by two small parties of New Mexican militia from Las Vegas, pursued a small band of Jicarillas who had been raiding in the vicinity of Las Vegas. They followed the Indians along the Mora River and overtook them at a point about 35 miles from the post near where the Mora joins the Canadian River. Maxwell was in the lead of a few soldiers who chased the Indians up a hill. At the top Maxwell was killed immediately by a volley of arrows. Four Indians, including at least one of those who shot Maxwell, were killed in the engagement. At least two dragoons were wounded. [61]

At this point both sides stopped fighting and Brigadier General Garland reported that "the Jicarilla Apaches are pretty thoroughly subdued" and "making overtures of peace." They had learned, Garland stated, that "they are not safe from pursuit in the most inaccessible parts of the Rocky Mountains." Garland had high praises for all the officers and troops involved in the war against the Jicarillas, and expressed delight that he and Acting Governor Messervy had "acted in perfect harmony." Most of the militia volunteers were released before their term of service expired because it was believed the Jicarillas were ready to end the conflict. Chief Chacon offered to make peace in August and met with Governor Meriwether in September. But Chacon did not represent all the Jicarillas, many of whom were not yet ready to give up without further struggle. No peace agreement was concluded and preparations were begun at Fort Union, where Colonel Thomas T. Fauntleroy replaced Cooke as post commander on September 18, 1854, to resume the campaign against the Jicarillas and the Utes in the spring of 1855. [62]

During the winter of 1854-1855 the Jicarillas and Utes began raiding because they needed food, hoped to destroy some of the frontier settlements, and possibly saw it as a way to alleviate the frustrations of encroachments on their territory and way of life. They committed acts of desperation before surrendering to the inevitable. In November they drove off a herd of cattle and several hundred sheep about 25 miles southeast of Fort Union. Although Fort Union was undermanned and some of the troops were in tents because the quarters were unsafe, Fauntleroy sent a detachment which recovered some of the cattle and sheep. In December troops were sent from Los Lunas and Fort Fillmore to investigate reports of raids by Jicarilla and Mescalero Apaches along the Pecos River. [63] The New Mexico Territorial Legislature reported at the end of 1854 that during the previous year Indians had killed 50 citizens and destroyed property worth $100,000. [64]

Although most of the Ute Indians of northern New Mexico Territory had refused to join with the belligerent Jicarillas during the campaigns of 1854, they permitted many Jicarillas to join their camps around the San Luis Valley during the autumn and winter. Soon Jicarillas and Utes were joining together in raids on the settlements, and the army had to conduct military operations against both tribes during 1855. On December 25, 1854, a combined force of Jicarilla and Ute warriors attacked the settlement of Pueblo on the Arkansas River in present Colorado, killing fourteen men, wounding two men, capturing one woman and two children, and taking 200 head of livestock. [65]

This assured that a major campaign would be organized against them as soon as possible in the spring. Major Blake, commanding at Cantonment Burgwin, was called to Santa Fe by Garland on January 12 to help arrange for a campaign against the offenders. Captain Horace Brooks, commanding Fort Massachusetts, was informed that an expedition would be organized and directed to use troops from his garrison to gain information about the Indians' "whereabouts." On January 13, 1855, Captain Carleton, commanding the Post at Albuquerque, was directed to prepare his company of dragoons for "active field service" and to join later with other troops in the department in a campaign against Indians (Carleton was used in the campaign against the Mescaleros instead of the one against the Utes and Jicarillas). Colonel Fauntleroy would lead the expedition, including troops from Fort Union. [66]

While preparations were being made, the raids continued. On January 11, 1855, Mescalero Apaches attacked at Galisteo (about 25 miles south of Santa Fe), "killed one man, wounded another, stripped a dozen women and drove off seventy mules." Fauntleroy was directed to send troops from Fort Union to cut off the raiders if they headed toward the Canadian River. A detachment was out four days and found no signs before returning to the post. Troops were also sent from Fort Marcy at Santa Fe, and they overtook the raiding party, killed three, and wounded four before the Indians escaped. On January 19 a combined force of Utes and Jicarillas again struck at Pueblo, killing four citizens and stealing approximately 100 head of livestock. The combined force of Captains Richard S. Ewell and Henry W. Stanton, which had been searching for hostile Mescaleros, attacked a Mescalero camp in the Sacramento Mountains of southeast New Mexico on January 20 and killed twelve Indians, including three chiefs. Captain Stanton and two privates were killed in the engagement. [67]

Colonel Fauntleroy led a detachment from Fort Union on January 25, 1855, to see if he could locate the Jicarillas and Utes who had attacked Pueblo. He returned on February 5 without success. Nothing much could be done until winter was over and a large command could take the field, and the raids continued. On February 8 a party of New Mexicans were attacked at Ocate by eight Indians who killed one of their party and stole five or six horses. A small detachment was sent from Fort Union the following day to investigate. They found the dead citizen but saw no Indians. Fauntleroy also received reports of Indian raids near Las Vegas. Kit Carson reported from Taos on February 28, 1855, that the Jicarillas and Utes were raiding without restraint, and the following day he wrote that they "have been committing thefts, robberies and murders upon the stock and inhabitants of this northern portion of the Territory." [68]

In preparation for a spring offensive Governor Meriwether, at the request of Brigadier General Garland, called for a militia battalion of mounted volunteers to join with the regular troops against the Indians. Lieutenant Colonel Ceran St. Vrain commanded the six companies of volunteers who were outfitted at Fort Union. Colonel Fauntleroy was placed in charge of military operations in the area, including troops at Fort Union, Fort Massachusetts, and Cantonment Burgwin. Captain Daniel Rucker, quartermaster at Fort Union, was named quartermaster of the campaign. The Jicarillas and Utes increased their attacks along Ocate Creek, the Canadian River, near Las Vegas, and in the San Luis Valley, stealing several thousand head of livestock. [69]

One of the mounted volunteers was First Sergeant Rafael Chacon, Captain Francisco Gonzales's Company B, whose memoirs covering much of his remarkable life, 1833-1925, have been published. Soon after the volunteers received their arms and equipment at Fort Union, before the campaign began, Chacon was part of a detachment sent from Fort Union in pursuit of Jicarillas who had seized a herd of horses from Juan Vigil of La Cueva, located between Fort Union and the village of Mora. The volunteers followed the trail of the stolen horses past Wagon Mound and through the Raton Mountains to what is presently known as Long's Canyon, a side canyon of the Purgatoire River in present Colorado, where they caught up with the thieves. As Chacon recalled, "the Indians fled from us, abandoning their camp where they had been making a meal on horse meat. Our own provisions at this time had been exhausted, and we ate the meat which the Indians had left." The Indians got away with the stolen horses which were not recovered. [70]

The Indians had split up, dividing the stolen horses, and the volunteers also separated to pursue them. "I got lost," Chacon remembered, "with four soldiers, and on the following day we killed a wildcat, which, for lack of better food, we were obliged to eat." Unable to regain the lost horses, "we returned to the fort to provide ourselves with a fresh supply of food and ammunition in order to continue the campaign." [71]

On February 20, 1855, Fauntleroy left Fort Union under command of Captain Joseph Whittlesey, traveled to Taos where he made additional preparations for the campaign, and proceeded the following month to Fort Massachusetts where he gathered his force of 500 men, including two companies of dragoons, four companies of mounted volunteers, and thirty spies and guides under command of Captain Lucien Stewart from Taos. Indian Agent Carson accompanied the campaign. [72]

Fauntleroy led his troops into the field on March 14, heading into the San Luis Valley. The primary mission of the campaign was to find and punish the bands led by Ute Chief Blanco and Jicarilla Chief Huero, believed to be the ones responsible for the attacks on Pueblo. After traveling approximately 100 miles northwest of Fort Massachusetts the troops had a brief engagement on March 19 near Saguache Pass with a camp of Utes and Jicarillas, during which seven Indians were killed. The Indians had seen the soldiers coming and resisted until their families made good their escape. As the soldiers followed the trail the Jicarillas split from the Utes and soon scattered, making it impossible for the troops to pursue all the Indians. The command followed the largest group (Chief Chacon and his followers) to a camp on the headwaters of the Arkansas River. There the troops captured most of the Indians' horses, but the Jicarillas managed to escape. [73] Fauntleroy did not follow because his men needed supplies, and he returned the expedition to Fort Massachusetts via Mosca Pass. Carson returned to his agency at Taos. [74]

As soon as his command was ready to march again, Fauntleroy took part of them back to the San Luis Valley to try to find the Utes, and St. Vrain led the remainder of the force across the Sangre de Cristo range in an attempt to locate the Jicarillas in present Colorado. Fauntleroy picked up the trail of Chief Blanco's Moache Utes and pursued them. His soldiers attacked the Indians in camp near the Arkansas River about 20 miles from Poncha Pass on April 28. The Indians had been up all night celebrating a scalp dance and were completely surprised. The soldiers, as Fauntleroy reported, "swept the enemy like chaff before the wind," killed an estimated forty Utes, wounded many more, and captured six children, thirty-five horses, twelve sheep and goats, six rifles, five pistols, twenty-five bows with arrows, and all the baggage, including over 200 buffalo robes and 150 pack saddles. Only two soldiers had been wounded, one of whom died later after his leg was amputated. A soldier was killed after the battle while attempting to pursue the fleeing Utes. Chief Blanco escaped with the rest of his band, and the soldiers followed and attacked a portion of the Ute band on May 1 and 2, killing four more Indians and capturing thirteen horses. Blanco and most of his people again escaped with the troops in pursuit. Chief Blanco appeared on a high ledge and asked to make peace, but one of the soldiers shot at him. The Indians then eluded the soldiers and scattered, making further pursuit fruitless. Fauntleroy returned to Fort Massachusetts in May. He rejoined the garrison at Fort Union in July and resumed command of the post on July 20. [75]

Meanwhile St. Vrain's command had followed the trail of the Jicarilla Apaches in present Colorado. They attacked a camp of Jicarillas on Bear Creek, a tributary of the Cucharas River, [76] killing and wounding thirteen, from where the survivors fled to the Purgatoire River. On the Purgatoire they struck the Jicarillas again, killing four and taking six women and children prisoners who were sent to Fort Union to be held until the conflict had ended. [77] In May the volunteers searched for Jicarillas along the Canadian River without success. They marched to Fort Union for supplies and prepared to take the field again. In June they caught up with a party of Jicarillas in the mountains of present southern Colorado and attacked, killing six, capturing seven, and taking thirty-one horses. The remainder of this band reportedly scattered, making pursuit impossible. A party of Jicarillas reportedly killed eight or ten New Mexicans in the mountain settlements between Cantonment Burgwin and Mora, but the offenders were not found. The enlistment period for the volunteers expired at the conclusion of six months and they were discharged at the end of July 1855 with high praises from Brigadier General Garland. [78]

The Jicarillas and Utes were tired of running and ready to make peace. They were practically destitute and were eating their mules. In August 1855 Governor Meriwether met with a delegation of Jicarillas and Moache Utes, and peace treaties were signed with the Moache Utes on September 11 and with most leaders of the Jicarillas on September 12. The Indians agreed to stop raiding and to give up claims to all lands except for reservations to be established for them. In addition to protected reserves, they were to receive rations, blankets, clothing, household utensils, agricultural implements, and seed. The treaties of 1855, like those of a few years earlier, were not approved by the Senate. New Mexicans, who did not want the Indians located close to the settlements, petitioned President Franklin Pierce to reject the treaties. Even though the agreements were not implemented, most of the Indians stayed near their agencies at Abiquiu and Taos, drawing their rations which were continued even though the treaties were rejected. The rations were considered a temporary expedient until permanent reservations were established. A few Jicarillas who refused to make peace continued to raid periodically near Mora and Rayado. One of the Jicarilla chiefs, Apache Negro, refused to participate in the peace arrangements in September 1855 but came to Santa Fe in March 1856 and promised to abide by the treaties. The Jicarillas did not receive a permanent reservation until 1887. [79]

In 1861 the Taos agency was moved to the Cimarron agency, and Indian Agent Carson was replaced by William F. N. Arny. Lucien Maxwell leased a two-square-mile area to the agency and contracted to supply rations to the Jicarillas. Arny hoped to get the Jicarillas to farm, but his successor in 1862, Levi Keithly, was not interested in farming and distributed rations from Maxwell's flour mill at Cimarron. Troops from Fort Union were temporarily stationed at Cimarron from time to time to help keep the peace and oversee the distribution of rations. [80]

By the time the Jicarilla Apaches and Utes were brought under control in 1855, the Comanches were causing alarm in New Mexico. They began visiting ranches along the Pecos River in the late spring months, taking livestock for their food supply. They took 200 sheep from Maxwell's Ranch at Rayado in July. Upon receipt of a report in September that 250 Comanches were destroying crops and livestock near Hatch's Ranch on the Gallinas River (33 miles southeast of Las Vegas and 13 miles east-northeast of Anton Chico), Fauntleroy sent Lieutenant Robert Johnston, First Dragoons, with 30 dragoons from Fort Union to the area with 12 days' rations to provide protection for settlers. Garland considered the Comanche threat serious because he believed they were being pushed out of their traditional lands in Texas. He sent Captain William T. H. Brooks, Third Infantry, with 45 men from Fort Marcy and Captain Carleton with 80 dragoons from Albuquerque to join the other troops at Hatch's Ranch. Garland directed the officers to attempt to meet the Comanche leaders "to warn them of the necessity of departing from New Mexico and returning to their own country." He directed Captain Brooks, senior officer and commander of the troops at Hatch's Ranch, to "open a communication" with the Comanches and "inform them, explicitly, that they will not be permitted to remain in this territory." Brooks was directed to avoid hostilities with the Comanches if at all possible, but punish them if necessary. Other than stealing some green corn and a few beef cattle, the Comanches caused no other destruction and left the territory within a few days. The troops sent to Hatch's Ranch returned to their previously-assigned stations. Garland reported at the end of October that all the Indians in the department had been quiet the preceding month, "not even a theft has been committed." Hatch's Ranch was considered to be a strategic location in the area because it was close to the Pecos River settlements, near the Fort Smith route to Albuquerque, and in an area through which Comanches and Kiowas often entered the settled regions of New Mexico. The ranch become a military outpost in the department the following year. [81]

The Indians remained quiet during the winter of 1855-1856, except for the Gila Apaches in southwestern New Mexico, and in February the mail escorts by troops from Fort Union on the Santa Fe Trail were discontinued because their was no apparent threat to travelers. When the February westbound mail failed to arrive in New Mexico, the cause was severe snow storms, not Indians. A detachment was sent from Fort Union as far as Rabbit Ear Creek to provide relief for the mail party but returned without meeting the mail because of the "immense fall of snow." It was later learned that the mail party had turned back to Missouri because of the weather. [82]

Despite the severe winter, which caused many Indians to suffer for want of provisions and tied them down because of the difficulty of traveling through deep snow, there were still many reports of Indian depredations which had not in fact occurred. Brigadier General Garland declared, "there is, I regret to say, an obvious desire to keep up, on the part of some of the citizens, an Indian excitement, and in consequence, we are annoyed by many false rumors." [83] Nevertheless, reports of Indian hostilities had to be investigated in case they were true. Alexander Hatch, as will be seen, was an example of someone who profited from the presence of troops.

Military operations took many forms and were not always directed at Indian problems. In March troops were sent from Fort Union in an attempt to catch deserters and recover property they had stolen when they took early leave from the army, apparently at Albuquerque. Lieutenant Johnston and 20 dragoons left Fort Union during the night of March 24 to take an indirect route to Point of Rocks (or as far as Rabbit Ear Creek if necessary) in order to get ahead of the wagon trains that had recently left for Missouri. The troops were to march back toward Fort Union, examine each train they met for deserters and stolen military equipment, arrest any deserters, and take possession of any government property they found. They examined eight trains and found nothing. They returned to the post on March 30. [84]

The Navajos began raiding during the summer of 1856, but most of the other tribes that had signed treaties the previous year were quiet. In June seven unarmed New Mexicans were killed by Indians near Mora, and a band of Jicarillas were charged with the outrage. Garland, however, was assured by the agent at Abiquiu that the parties blamed had not been absent from that area. The department commander believed that the deed may have been done by a large war party of Cheyennes and Arapahoes who had crossed the Sangre de Cristos to attack the Utes, killing fourteen of them. He concluded before the facts were known that "it is quite probable that a fragment of this war party visited the Moro settlement on their return and committed the murders attributed to the Jicarillas." Apparently no troops were sent in pursuit. A month later Garland confirmed that the guilty parties were "the Indians of the Arkansas River, not within this Department." [85]

Sometimes the Indians were blamed for what they did not do. In the autumn of 1856 a report reached Fort Union that a number of sheep had been killed near Wagon Mound, presumably by Indians. A detachment was sent out by the new post commander, Lieutenant Colonel W. W. Loring, to investigate and found the report was true. The perpetrators left a trail which was followed to Mora, where it was found that a party of New Mexican hunters and traders were responsible. A short time later, Colonel B. L. E. Bonneville (who was serving as department commander while Garland was on leave of absence) stated that "the Indians, generally, are quiet, except occasionally a few thefts, committed by roving bands or by Mexicans." [86]

Comanches and Kiowas returned to New Mexico in September 1856, taking food from the ranches as they passed through the Pecos Valley area. One party of warriors from the two tribes pushed beyond the Rio Grande to attack the Navajos and lost many of their horses. When they returned to the plains, they took some livestock from the settlers. Mostly they took enough for their food supply but did little other damage. [87]

According to historian Charles Kenner, the Comanches had come into New Mexico for decades to trade and "helped themselves to foodstuffs." They did not consider this raiding, and the New Mexicans had tolerated such behavior. The Anglo ranchers, such as Alexander Hatch, Preston Beck, and James M. Giddings, considered the taking of food to be raiding and called on the army for protection. [88] When the Comanches and Kiowas took corn from Hatch's Ranch in September, Hatch requested that troops come to the area as they had the year before. Garland, just before he left the territory, sent Captain Washington Lafayette Elliott and his Company A, Regiment of Mounted Riflemen, to search for a suitable location to station troops near Hatch's Ranch and to establish quarters there for the winter to protect the area. [89]

Captain Elliott inspected Beck's Ranch and found the road bad, wood scarce, and the water of poor quality. He found Hatch's Ranch to be the best place for troops. There were enough buildings to "afford comfortable shelter for my company, men & horses for the coming winter." There was plenty of wood and water, and Hatch had, despite his claims that the Indians had destroyed his crops, "corn sufficient to supply the company until about Apr. 1st next." There were more settlers around Hatch's Ranch than at Beck's, so troops stationed at Hatch's Ranch would be better positioned to protect the livestock in the vicinity. Lieutenant Colonel Loring, regimental commander of the mounted riflemen and commanding officer at Fort Union, endorsed Elliott's choice and sent Elliott's company from Fort Union on November 4 to take station at Hatch's Ranch. [90]

Captain Elliott, Lieutenant William B. Lane, Second Lieutenant John H. Edson, and 73 enlisted men of Company A, Regiment of Mounted Riflemen, established the post, which Elliott called Fort Biddle, on November 7, 1856. His proposed name was not approved and the post was known as Hatch's Ranch. It was occupied off and on, depending on the threat of Indian troubles, into the Civil War. It was generally considered an outpost of Fort Union, from which troops and supplies were typically sent, and the activities of the garrison at Hatch's Ranch were often coordinated with the actions of troops at Fort Union. For example, on December 26, 1856, department headquarters appended the following note to a letter to the commander at Fort Union regarding plans for a possible campaign against the plains Indians: "It is understood, as a matter of course, that Captain Elliott's Company [at Hatch's Ranch] is under your instructions, as regards any service you may deem proper to require of it." Even so, Hatch's Ranch had its own commanding officer who ordinarily reported directly to the commander of the military department. Just prior to the Civil War the post at Hatch's Ranch was considered as a possible replacement for Fort Union. [91]

Hatch's Ranch was located about 65 miles from Fort Union on a flat area about one-half mile west of the Gallinas River, approximately one-quarter mile south of where Aguilar (Eagle) Creek joins the Gallinas. Hatch had called his place Eagle Ranch for a short time but soon changed it to Hatch's Ranch. Hatch furnished land for the post and apparently some buildings used by the troops without charge or for a nominal payment but made his money supplying corn and hay for the garrison. Lieutenant Edward F. Beale, in charge of improving the Fort Smith road, spent almost two months at Hatch's Ranch in late 1858 and early 1859. He described Hatch as "being a shrewd man" who "makes large profits by taking contracts for the delivery of grain or selling it at his house." Beale noted that Hatch had "some ten thousand bushels of corn which he was selling at over one dollar a bushel to the government and others." Hatch was later appointed post sutler for the troops stationed at his own ranch. He and his neighbors benefited from the protection of the troops. More settlers came into the area, and New Mexicans established the village of Chaparito about three miles north of Hatch's Ranch. The new community served as a base for Comancheros, buffalo hunters, and herders, and it provided entertainment for the troops at Hatch's Ranch. [92]

|

The troops at Hatch's Ranch spent the first several weeks erecting shelter for themselves and their horses. Although Elliott had implied in his initial report that Hatch would provide buildings for the men and horses, he may have only provided the space for them to construct their own quarters and stables. The buildings were completed on December 15. It is not clear what building materials were used at that time, but the quarters at Hatch's Ranch were later described as built of stone. The garrison remained there, sending out an occasional scouting party to keep a watch for hostile Indians, until March of 1857 when they returned to Fort Union. [93]

One of the inhabitants of the post was Lydia Spencer Lane, wife of Lieutenant Lane, and author of I Married a Soldier, a source on the social life of the army in the Southwest. Lydia Lane was a sister to Valeria Elliott, wife of Captain Elliott, commanding officer at Hatch's Ranch. The Lanes had a one-year-old daughter. Mrs. Lane probably expressed the feeling of many of the troops, too, when she later wrote of Hatch's Ranch: "When we saw the ranch we felt somewhat melancholy at the prospect of spending the winter in such an isolated spot, so far from everywhere." The Lanes and Elliotts lived together in the same building occupied by Hatch and his wife, "a long, low, adobe house, with a high wall around it, except in front." [94]

There was no surgeon assigned to Hatch's Ranch, Mrs. Lane noted, "so we tried to keep well." Some nonprofessional medical care was available: "A Mexican man and his wife went about sometimes to officiate in particular cases. . . . I think their performances would have made the scientific physicians of the present day open their eyes." The Lanes felt isolated but survived the winter at Hatch's Ranch without incident. Lydia and Valeria were fortunate to have each other's companionship at the outpost. "We passed a very quiet, though pleasant, winter;" recalled Lydia Lane, "but we were by no means sorry when the company was ordered to Fort Union in the spring." [95]

At the same time plans were being made in the autumn of 1856 to station troops at Hatch's Ranch, Kiowa Indians were threatening Bent's New Fort on the Arkansas River where the army had stored supplies. This also resulted in the involvement of troops from Fort Union. William Bent had abandoned and destroyed Bent's Old Fort in 1849, and he built Bent's New Fort near Big Timbers on the Arkansas River in 1853. Bent continued to trade with the plains tribes. In October 1856 Bent returned from a trip to Missouri and discovered that the man he had left in charge of the trading post while he was gone had been giving whiskey to the Indians. This was illegal under the Indian trade and intercourse act of 1834, and Bent knew he could lose his license to trade. This occurred while James Ross Larkin was at Bent's New Fort, and Larkin left a record of what happened. [96]

On October 14, 1856, Bent dismissed the employee (identified by Larkin only as "a Frenchman"). Some Kiowas, who had received whiskey from and were friends of the discharged man, protested to Bent and made trouble, even threatened to kill Bent. The Cheyennes present defended Bent and his trading post, moving inside the fort to assist in case the Kiowas attacked. Bent's wives were both Cheyennes and he had many friends among the members of the tribe. He had traded with them for over 20 years. An uneasy impasse remained at the trading post when Larkin left on October 26. [97]

A few days later, on November 1, the peace was broken. Bent wrote to his friend and former partner, Ceran St. Vrain, whom he addressed as colonel because of his rank in the New Mexico volunteers, "to inform you and the U.S. Troops that the Tug of war is now at hand, this evening we was attacted by the Kiowa Indians." The Cheyennes had repulsed the attack, killed one Kiowa, and taken several horses from them. Bent praised his defenders, "the Cheyennes are doing all they can to protect the whites and the Fort." Although St. Vrain lived in Mora, the letter was sent to Fort Union where St. Vrain arrived on November 8. Bent especially wanted to "notify you and the U.S. Troops what is going on, as U.S. have a great many stores in my warehouse and no one here to protect them, but myself, a few men, and the Cheyennes." [98]

Bent expressed concern that "I shall have an awful time here this winter, with the Kiowas." Although the Cheyennes promised to fight the Kiowas, Bent stated "I would like to have some of the Troops come over and see what is going on, as war is going to rage in this part of the Country to some extent." Bent warned, "should not the Troops attend to this amediately it will be very trouble some traveling across the plains next season." Clearly he hoped troops from Fort Union would come to his assistance. [99]

St. Vrain sent the letter to Colonel Bonneville at Santa Fe, who directed Lieutenant Colonel Loring to send two officers and twenty enlisted men to Bent's Fort "with instructions, ostensibly, to look into the Commissary stores at that place. . . . The principal object, however, is to ascertain the state of affairs at that point in regard to Indian matters." Bonneville cautioned that the "strictest secrecy should be observed, that in the event of a campaign against the Kiowas, they may be taken by surprise." The officer in charge of the reconnaissance was to gather as much information as possible about the numbers, location, and disposition of the Indians. If it appeared the presence of troops at Bent's New Fort was required for the safety of the post and the government stores, the troops were to remain there and send an express to Fort Union. Otherwise they were to return to Fort Union as soon as practicable. [100]

Mounted riflemen were called from other posts to Fort Union to comprise the detachment sent to Bent's New Fort. A corporal and six privates were picked from Hatch's Ranch, and Second Lieutenant Alexander McRae, with one non-commissioned officer and fifteen privates, was called from Cantonment Burgwin. McRae was in charge of the reconnaissance. These troops returned to Fort Union on January 8, 1857, and reported that the situation was quiet at Bent's New Fort. [101] McRae also provided details about the Kiowas, who had gone to the Cimarron River about 200 miles from Fort Union for the winter, and what would be required to mount a campaign against them. Colonel Loring passed this information on to department headquarters, noting that a force of 400 to 500 well-mounted soldiers, with 100 Ute Indian guides, 50 wagons for supplies, and rations for three months should be sent in February if a successful campaign was to be made against the Kiowas. The commanding officers at all posts in the department were directed to be prepared for "active operations in the field . . . as soon as the grass will permit," if such became necessary. [102] If the Kiowas remained quiet, however, there was no immediate need for a campaign to punish them. But other Indian problems might require the services of troops in the department. [103]