|

Fort Union

Historic Resource Study |

|

CHAPTER FOUR:

LIFE AT THE FIRST FORT UNION

The structure and nature of society at Fort Union had much in common with every other military post in the country during the same era but little in common with society in any other place. Military organization, with its officer class and rigid rules of behavior for both officers and enlisted men, fostered a closed society that was, at least in theory if not in practice, less free and more highly structured than almost any other institution except, perhaps, some religious orders. By Congressional action the army had its own code of justice and military courts to try offenders of every rank. Everybody in uniform had a place in the hierarchy that was determined by assigned rank (a bureaucratic system in which promotions were difficult to earn and slow to accumulate), and dependents shared the status of the soldier of whose family they were a member.

Class lines between officers' row and the enlisted men of the garrison were almost as sharply drawn as the demarcation between slave owners and slaves. Most officers and their families considered themselves to be part of an aristocracy and made every pretense to emulate the privileged classes. The enlisted men were thought of and often treated as a servile force who made the upper-class status of commissioned officials possible. Some officers apparently thought enlisted men were devoid of the full range of human emotions. Lieutenant Henry B. Judd, Third Artillery, was shocked to discover in 1850 that the members of his company, serving at the Post at Las Vegas in New Mexico, were opposed to being split up and some of the men assigned to another unit. To Department Commander John Munroe, Judd wrote: "With such men the idea of separations from old and tried associations is like hushing up this whole current of life's pleasures. I had no conception until it came to the test that men of their class felt so deeply the ties which have bound them to each other." As a result, Judd requested that his company not be split, declaring that "the remaining detachment will be utterly useless and inefficient as a distinct body." [1]

That rigid structure was modified by the Civil War, after which the military society of the prewar years was looked back upon by some officers as "the good old days." William B. Lane served at Fort Union before and after the Civil War and held fond recollections of the relationship of officers and men during the 1850s. His views confirmed the attitudes of officers noted above. Looking back at the era before the Civil War from the perspective of the 1890s, two decades after his retirement from active duty, Lane (who was not a West Point graduate but had risen up from the ranks of enlisted soldiers of the Regiment of Mounted Riflemen during the Mexican War) wrote that the "faith, or confidence of the enlisted men in their officers, and the almost universal kind feeling of the officers for the men, in the old days, added much to the discipline and efficiency of our little army, and made things comfortable for both sides." [2]

By contrast with what happened to the discipline of enlisted men and a decline in status of the officer class, resulting from the changes brought about by the service of millions of volunteers during the Civil War, Lane declared of the prewar army that those "were the days before the enlisted man had to be 'smoothed down' with wire-bottom cots, the mattress, and the pillow." In addition, an enlisted man then was not "allowed to indulge in the doubtful pleasures and advantages of corresponding direct (and probably did not want to) with higher authority than his immediate commander, and the delight of an anonymous letter was unknown to him." [3] In lamenting what had disappeared, Lane verified the importance of enlisted men knowing their place, obeying their officers, and performing their duties.

On the other hand, the army provided every soldier with food, clothing, shelter, medical care, and periodic cash payments for military service. There was something of a balance involved; economic security was available for the surrender of some freedom, abiding by the rules, and working at whatever tasks were assigned. Those who could not adapt to these conditions frequently escaped from their obligations by deserting the army. Those who served out their terms of enlistment accommodated themselves to the system and followed orders most of the time. The large number of courts-martial would indicate, however, that many soldiers and officers were frequently in violation of one or more of the hundreds of army regulations.

The losses to desertion plagued the army throughout the nineteenth century. Statistics on desertion at Fort Union may be found in Appendix D. Although some were caught and returned to duty, many deserters succeeded in getting away. The escape of four enlisted men from Fort Union in 1852 resulted in tragedy. In September of that year four privates in the Third Infantry (last names were Hassey, Marodi, Paulus, and Phister; no first names were given) deserted from the post and headed for Missouri. They got as far as Wagon Mound the first night and followed the Cimarron and Aubry routes of the Santa Fe Trail. They had few provisions and depended on killing game for subsistence. Their weapons consisted of a musket and a revolver. [4]

At Bear Creek on the Aubry Route the deserters got into an argument about who should carry the weapons and other items. Private Paulus had the revolver and shot and killed Private Marodi. Paulus then attempted to kill Phister, but Phister and Hassey got the revolver away from Paulus and shot him in the head, killing him. Phister and Hassey proceeded to the Arkansas River, where they were apprehended and returned to Fort Union. Private Hassey escaped again but was quickly apprehended, and he and Phister were placed in irons and kept under guard. Hassey attempted to commit suicide by "cutting his throat" but survived. Carleton recommended that the two prisoners be turned over to civil authorities for further investigation of the murders, but the final disposition of their cases was not found. [5] Not all deserters were so unfortunate, and the fact that soldiers continued to escape military duties in large numbers was indicative that army regulations were not acceptable to all enlisted men.

Whatever the assignment, there was a strict chain of command throughout the military system. Orders came from the top down, and reports went the opposite direction. Almost nothing was done without benefit of an order, and almost every duty required the ubiquitous report plus the endorsement of officers up the bureaucratic chain. Among officers rank always had its privileges, constantly evident at a military post. Quarters, for example, were assigned to officers by rank, not by size of family. Any officer who outranked another could claim the housing of a subordinate. An unmarried officer of higher rank than a married officer was entitled to occupy the choice of available facilities without regard to the needs of the married officer's family. The dependents of officers had no legal status in the army. Whenever a new officer arrived at a post, he could take the housing of any officer who was subordinate in rank or seniority. The officer turned out could then expel any of his subordinates from their quarters, sometimes forcing the lowest ranking officer (and his family if he had one) to live in a tent. It was sometimes compared to a game of musical chairs.

One officer's wife, Mrs. Orsemus Boyd, who lived at Fort Union in 1872 and 1873, described the practice as she experienced it at a post in Texas. The process was similar at all posts, but not everyone was as accommodating as Mrs. Boyd.

Fifty times, perhaps, there was a general move of at least ten families, because some officer had arrived who, in selecting a house, caused a dozen other officers to move, for each in turn chose the one then occipied by the next lower in rank. We used to call it "bricks falling," because each toppled that next in order over; but the annoyance was endured with great good nature.

. . . An onlooker would doubtless have found the anxiety experienced by the officers' wives amusing; for though prepared for the worst we were, of course, solicitous. [6]

Mrs. Boyd managed to avoid being ranked out on one occasion, but only temporarily. The Boyds occupied fairly commodious quarters which were wanted by an unmarried captain on his arrival at the post. Mrs. Boyd was expecting her third child, and the post surgeon "declared I could not be moved." She delivered a son the following day. While she recovered, Mrs. Boyd "indulged a delusive hope that the officer who had chosen our home would be content to remain" in his small quarters. "I felt," she asserted, "that a bachelor could live less inconveniently in one room than could a family of five." Nevertheless, she disclosed, "the very day baby was four weeks old we were obliged to move." The Boyds resided in that one room for the next two years. [7] Their situation was not unique.

Although the quarters provided for the few women laundresses who were wives of enlisted men were small and inferior in comparison to officers' quarters at Fort Union, the laundresses usually were not subject to such practices as "ranking out." In addition, laundresses received official military recognition while officers' wives did not. The military acknowledged a need for laundresses, and regulations permitted up to four per company (it was not unusual, however, for there to be more than four). Most laundresses were wives of enlisted men, who were only permitted to marry with the permission of their commanding officer. That permission was seldom given unless the enlisted man's intended wife agreed to serve as a company laundress. Occasionally an enlisted man's wife was permitted to work as an officer's servant. Some laundresses were not married. [8]

Laundresses were provided quarters and rations. When buildings were erected at Fort Union, the laundresses' quarters were north of the hospital. Laundresses were authorized to charge each soldier so much for washing his clothing and bedding (approximately $1.00 per month on average). Some laundresses supplemented their income by engaging in prostitution, a "profession" always in demand at a military post where most of the enlisted men were single and forbidden to marry. Other women camp followers also provided such services to the troops. Army regulations were quite tolerant. The only offense for which they could be banished from contact with troops was venereal disease infection. [9] Some laundresses had children, who were also a part of garrison life. Laundresses were always present at Fort Union, but almost nothing has been found about them. Occasionally there was mention of a laundress in the records.

In 1873 one laundress at Fort Union was moved so her quarters could be assigned to another laundress (this was similar to ranking out, although rank apparently played no part in it). On May 16 the post quartermaster was directed to move Mrs. Ramis, laundress for Troop L, Eighth Cavalry, from room fourteen to room thirteen and assign rooms fourteen and fifteen to Mrs. Montgomery, laundress for Company C, Fifteenth Infantry. Mrs. Montgomery was the wife of Private John J. Montgomery, who was assigned to duty as a nurse in the post hospital. Although no explanation was given for changing quarters for Mrs. Ramis, it should be noted that the post commander, Captain H. A. Ellis, was an officer in the Fifteenth Infantry. Perhaps he was simply making certain that laundresses for his regiment were given preference over laundresses for the Eighth Cavalry. [10]

The daily life at the post was regulated by a strict schedule, which usually began at daylight when a cannon was fired and the flag was raised. The calls to various activities and duties were sounded by drums and bugles. After morning assembly came the call to breakfast, which was followed by sick call and calls to duty assignment, drill, target practice, or other jobs. At noon came the call to dinner, followed by more work during the afternoon. The supper call at evening was followed, at sunset, by the lowering of the flag and firing of the cannon. The soldiers were to be in their quarters when retreat was sounded, and the day ended with taps. This routine was interrupted for special inspections, dress and undress parades, and other periodic ceremonies. [11]

The soldier, officer or enlisted man, spent only a part of his time performing military duty and had considerable leisure time. The nineteenth-century army provided few if any activities for free time, leaving each individual to do as he desired within certain limitations. Absence from the post, for example, was restricted to permission. Soldiers engaged in numerous activities for recreation and relaxation, including drinking of intoxicants (drunkenness was a serious problem for the army throughout the time Fort Union was an active post), gambling, playing cards, patronizing prostitutes, racing, boxing, wrestling, swimming, dancing, fishing, hunting, picnicking, presenting and attending dramatic performances, visiting, storytelling, reading and writing for those who were literate, and watching nature. [12]

The stories of vice, of soldiers in trouble and in violation of military regulations, are abundant because of the numerous courts-martial, topics that will be considered in a later chapter. Unfortunately for students of social history, except for those court proceedings which provide a distorted view of humanity by focusing only on misconduct, official military records reveal little about the daily lives of soldiers and citizens who resided at military posts, particularly what they did with their own time that was not depraved, criminal, immoral, illegal, impure, dishonest, or evil. One must search for the few remaining personal letters, diaries, journals, and reminiscences to gain some understanding of the ordinary and everyday activities of a few individuals and to draw general conclusions about the larger society in which those individuals functioned. At best, the results are often cursory and anecdotal. Because of the paucity of records kept by enlisted men, much more is known about the lives of officers and their families. This imbalance of reliable information contributes to the difficulty of telling the story of the private soldier except in generalities. It is much easier, because of more sources, to provide an understanding of some individuals among the officer class.

The difficulty of explaining the living conditions of enlisted men is exemplified by the lack of solid information about such basic items as the furnishings of their barracks during the 1850s. According to Arthur Woodward's 1958 report on Fort Union, apparently based on data gathered about a number of similar frontier military installations, the men slept in two-tier wooden bunks with wooden slat bottoms, constructed along the walls. While it was typical of the military at the time to have four men sleep in each bunk (two up and two down), one can only speculate that this was the situation at Fort Union. The bed sacks were periodically filled with dried grass or straw. Rolled up clothing might serve as pillows. Each soldier was issued two blankets which he used in quarters and on field duty. [13]

Other furnishings in the barracks, including chairs, tables, and desks, were fashioned from packing crates, boxes, barrels, and other available materials. The quarters were apparently lighted by candles and heated by fireplaces. Exactly how the barracks were arranged, how the kitchens and mess rooms were furnished, how personal hygiene was accomplished (what bathing facilities, if any, were provided), how the latrines were equipped and situated, and all the other details that would shed light on the daily life of the enlisted men at the first Fort Union remain virtually unknown. [14]

It is known that a variety of nationalities were represented in the army and made up the polyglot society at all military posts, including Fort Union. In addition to Anglo- and Hispano-Americans, there were large numbers of Irish, German, and British soldiers. Representatives from a number of other countries and ethnic groups were often present, including French, Scandinavian, Italian, Slavic, and others. Afro-Americans were present at Fort Union as slaves and servants before the Civil War and as soldiers and employees after that conflict. The army, perhaps more than any other American institution of the era, exemplified the ethnic diversity of the nation.

The initial garrison of Fort Union, when established by Major Edmund B. Alexander on July 26, 1851, was comprised of one company of infantry (Company G, Third Infantry) and two of dragoons (Companies F and K, First Dragoons). These soldiers were joined the following day by Company D, Third Infantry, making a total aggregate garrison of 339 officers and men. Because of troops absent on assignments, on the sick list, or under arrest, the number of troops available for duty and extra duty at the post at the end of July 1851 was only 197. [15]

Until buildings were erected at Fort Union, officers and their families, enlisted soldiers, and employees lived in tents, and the quartermaster, commissary, and ordnance stores were protected only by canvas covers and armed guards. Many of those who had been stationed in Las Vegas and Santa Fe were not happy with the move from what, by comparison, had been comfortable quarters. The tent accommodations, however, were intended to be temporary, and the construction of quarters held top priority at the new post.

Inadequate quarters were not the only thing about which some military officers could be unhappy. Some officers held an exalted view of their own position and were determined not to associate on the same level with the common people. Lieutenant J. N. Ward, Third Infantry, had been in the army for ten years and had served enough time in New Mexico that he was granted a furlough late in 1851. He planned to travel to the states, perhaps to visit his family in Georgia, but was disappointed with the travel accommodations available.

Ward complained to Lieutenant John C. McFerran, quartermaster department and adjutant to Colonel Sumner, that the "man in charge" of the wagon train "in which I was to have left for the United States" expected the officer to pay 25 cents per pound for his baggage. Even worse, "I was to perform guard duty on the trip with the teamsters, and was to assist in guarding and hitching up animals at all times." Although he wanted to take his furlough, Ward declared "I can not consent to travel in such manner." [16]

Ward's class-conscious snobbery was confirmed when he wrote, "if I were with a Government train, with men whom I could command, I would not object to perform any duties however arduous, but I can not think of associating myself as an equal, with the class of men who compose the teamsters of the plains, if I never go on furlough." "There is," he remarked, "no gentleman that I know of, going in with the train which leaves today." Therefore Ward requested that Sumner issue orders for him "to remain at Fort Union, or wherever else he may select on temporary duty . . . until such time as an opportunity offers for my leaving for the U.S." [17]

Sumner's response to Ward's plea was not located, but the lieutenant was a passenger on the mail coach conducted by William Allison which left Santa Fe on December 2, 1851. The mail party was stopped by blizzards at McNees Creek and Fort Atkinson. Lieutenant Ward left the coach at Fort Atkinson because he was too ill to travel. He remained there until Francis X. Aubry came by with a train of twelve wagons in January 1852 and traveled with Aubry to Independence, arriving there February 5. [18] Presumably Allison and Aubry were "gentlemen" with whom Ward did not mind associating.

Not everyone complained about the common people or conditions in New Mexico or Fort Union, although some officers' wives were apparently uninformed about both. One historian of frontier military social life claimed that "Army women were not well informed." Informed or not, an officer's wife faced many adjustments and difficulties. The same historian declared, "a woman who married an Army officer led a grueling life that usually shocked her at first and then tested her mettle as surely as ever the pioneer woman was tested." [19]

Some of the officers' wives at Fort Union probably would have agreed. Among the early residents of Fort Union was Catherine (Cary) Bowen (commonly known as Katie), wife of Captain Isaac Bowen, in charge of the department commissary stores. They accompanied the supply train that followed Colonel Sumner's column from Fort Leavenworth to New Mexico, arriving at the new Fort Union on August 21, 1851. In letters to her parents, Mrs. Bowen (23 years old when she arrived at Fort Union) provided some insight into life at early Fort Union, especially the private and social activities of the officer class. Her letters were generally characterized by a spirit of happiness and well-being. Occasionally Isaac Bowen wrote to his parents and added perspective on life at Fort Union. [20]

Following their arrival at the post, Katie wrote her mother, "at last at our destination, safe in every particular, in health, and our goods in as good order as anything could possibly be after the hard journey they have had." She had enjoyed the trip over the Santa Fe Trail from Fort Leavenworth. For her "the time did not seem long, for everything was pleasant, weather and country." [21]

Fort Union, she observed, was "located particularly with a view to extensive farming operations, and certainly it is well adapted, plenty of water, abundance of wood, and, to all appearances, a fertile valley, with mountains on two sides of us." Of the pine trees, she observed they made "good lumber and fire wood and will not fail a supply in thousands of years." The post "is supplied with a delicious spring and we have its water brought twice a day. For the stock and for irrigation there are several ponds and one lake. The river Moro runs six miles below us." The post office was still at Barclay's Fort on the "Moro." Katie considered the area "a pretty country" and obviously enjoyed being there. [22]

Isaac Bowen was a little less enthusiastic, declaring "We anticipated no very great enjoyment or pleasure from our residence in New Mexico and I am not certain that we have found anything worse than we expected." He described Fort Union as "about a hundred miles from Santa Fe . . . with plenty of wild prairie, mountains close in rear and in the distance front & left, good water, a fine bracing, healthy & salubrious climate." They had adjusted well to their new station. "Since we arrived here," he informed his father, "we have had no time to feel unhappy or scarcely grumble or find fault." Still, he had no appreciation for the land. "We will endeavour, however, to submit with a spirit of becoming resignation to whatever hardships may be our lot during the period of our residence here and when we leave the country, it will be with the wish that we may cast its dust from our feet forever." Speaking for himself and Katie, Isaac disclosed that "one great drawback is the want of mails. Could we hear from our friends oftener we would be better satisfied." [23] That view was probably shared by most officers and soldiers who had come from the East to serve in the unfamiliar land of New Mexico.

Katie, on the other hand, was very positive about the area and was happy that other officers' wives were at the new post when she arrived. She wrote to her mother that "the morning I came in, Mrs. Sibley took me to her house, or rather tents, and entertained me in the kindest manner." [24] A few days later she noted that "we were serenaded last night by the young gentlemen and kept awake so long that our nap this morning was longer than usual." "We will be," she predicted, "a very social garrison as soon as we are a little better acquainted." She was especially impressed with the young post surgeon, Thomas McParlin, describing him as "one of the pleasantest Men I have met for a long time and said to be very skillful." [25]

Until quarters were built, the Bowens lived in three "very nice" tents. [26] They were situated close to two other officer families, and Katie Bowen became close friends with Charlotte (Mrs. E. S.) Sibley and Mrs. E. B. Alexander (Mrs. Alexander's first name is unknown). [27] A few weeks after arriving at Fort Union, Katie informed her mother that "Mrs. Alexander, Mrs. Sibley and myself live on three sides of a triangle and the gentlemen make a great deal of sport of the triangular meetings." "In truth," she confessed, "we are nearly all the time together, if one is in the kitchen, the other two bring their sewing into the kitchen." At other times, "when we are dressed in the afternoon, we sit with our sewing sometimes at the house of one and sometimes at another." She explained to her mother, "I tell you these particulars that you may know that we do not give way to despondency or allow the better establishments of our friends in the states to make us unhappy." Any variety they had in their lives was the result of their own efforts, for Katie noted that "one day is very much like another here." [28]

|

|

| Isaac and Katie Bowen, courtesy of their granddaughter, Gwladys Bowen. | Dr. Thomas McParlin, courtesy of Maryland State Archives. |

Mrs. Sibley also adapted well to tent living, as she informed her cousin: "We are living very comfortably in our tents. . . . My husband is an old soldier and understands perfectly the management of all things connected with Army life." She was apparently proud of her situation, stating that "Our tents are put upon frames and are floored and carpeted. I have arranged them so that the word 'Cozy' would more properly apply in description of the interior than any word else." Of her life at the first Fort Union, Charlotte Sibley wrote, "My books, sewing, and visiting with the other ladies employ my leisure moments in the morning." [29]

Sophia W. Carleton, 22 years old and expecting her second child, [30] was staying at Barclay's Fort, where rooms were available, while her husband, Captain James H. Carleton, was on patrol. Besides Sophia Carleton, Katie Bowen and Charlotte Sibley were also pregnant. Mrs. Alexander, wife of the post commander and apparently several years older than the others, was a part of their little circle. Located at an isolated post, these women relied upon each other and shared experiences. Each apparently had a servant. The Bowens owned a young female black slave, Margaret. [31] Katie later wrote that Margaret "is a very good girl and cooks nicely, as well as being an excellent house servant. . . . Her mother is a free woman in Louisville and able to buy her, so if possible [when transferred from New Mexico], we will carry her to her mother or set her free." [32] Captain and Mrs. Carleton brought at least two slaves with them to Fort Union from Missouri (Hannah, age 28, and Benjamin, age 21), both of whom they later sold to Governor Lane. [33]

Katie watched her money carefully and managed her household scrupulously, sewing most of her own clothing and making other needed items. She noted that Charlotte Sibley "went into the extravagance of buying nice furniture." Katie, however, was proud of her own "home made lounges and benches" and explained how she was covering some extra pillows with "turkey red" to make their "two easy chairs," the frames of which they had had made at and brought with them from Fort Leavenworth, "charming." [34]

There were no gardens at Fort Union when they arrived because it had been occupied so late in the season, but vegetables were obtained from Las Vegas and the post garden at Rayado. The Bowens purchased some chickens at Las Vegas so they would have their own eggs, and they brought a milk cow with them from Fort Leavenworth. Katie did complain about the high cost of basic items in New Mexico, noting that butter sold for 75 cents a pound, sugar at 15 cents a pound, corn from $3.00 to $4.00 per bushel, and flour $20.00 to $22.00 per barrel. Everything officers bought from the commissary department included an additional eight cents per pound for freight from Fort Leavenworth. [35]

|

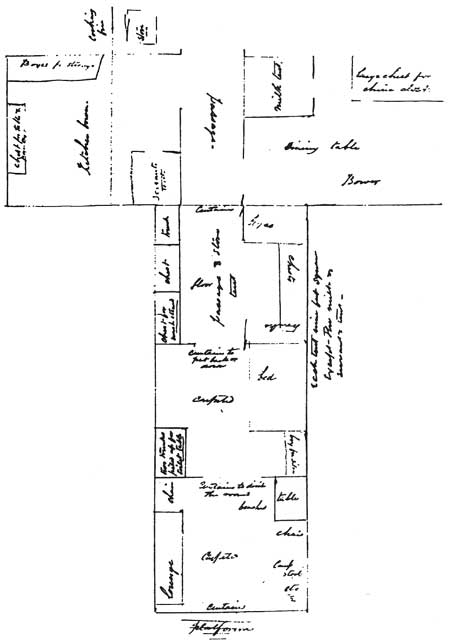

| Katie Bowen sent this drawing of the arrangement of their tents at Fort Union to her parents, and this copy was generously provided by Gwladys Bowen, granddaughter of Katie and Isaac Bowen. The three tents, each nine feet square, were placed on a platform and the floor was carpeted. The servant's tent and the milk tent were smaller. The kitchen and dining bowers were outside, as were the stove, cooking fire, and other items. The three tents were divided by curtains. This served as the home of the Bowens until quarters were built. |

Like everyone else who came to New Mexico in government service, the Bowens found the cost of living to be high. Katie declared, "It is rather tough for with what we pay for the commonest things here would buy us luxuries in the States." Because the only available place to buy rations was the commissary department, where "we are allowed to buy one ration for every member of our family which leaves us nothing for hospitality," Katie joined her peers in condemning Colonel Sumner's orders, in the name of economy, to have the cost of transportation added to the contract price of everything shipped from the East. [36] This was a new practice, an economy measure instituted by Colonel Sumner, but it was later rescinded because of the opposition.

When the sutler's store was opened by Jared W. Folger, however, Katie declared his prices "exceed anything I ever heard of. Happily we are independent of him." The Bowens had brought many commodities with them from Leavenworth, some of which they had purchased in Philadelphia and St. Louis. They were supplied with everything except "fresh meat and flour," and they were preparing an order for supplies from Philadelphia for the needs of the coming year. [37] Regarding local food supplies, she later noted that "the Mexicans bring in venison, wild fowls and onions and we manage to set a very comfortable table." [38] Katie took pride in her household management abilities, declaring "we live plain and well and have plenty of clothes." [39]

Katie was competitive and enjoyed making do. "I had a pint of cream yesterday," she boasted in her first letter from Fort Union, "and stirred up nearly a pound of butter in a tin cup just to say that I had made butter before Mrs. Sibley, who has been fixed a month and lived without butter and the milk of two cows and I have but one at present." Katie had brought 30 pounds of melted butter from Fort Leavenworth but just wanted "to have new butter." A few days later she made plum preserves. [40] Soon Katie and Charlotte Sibley shared a stone butter churn, butter paddle, and earthware pan for working butter, one using these on Tuesdays and Fridays and the other on Wednesdays and Saturdays. [41] In January 1852 she wrote, "I make plenty of butter yet and our hens lay finely we have 17." [42]

Katie was pleased with her accomplishments. "All of us ladies have had a great time making plum jelly to see who would succeed best. I never made jelly before, but never will be beat at anything." She was also proud of her "four mince pies" which "really tasted like home and did not cost a cent hardly." "All the husbands," she confessed, "cry out about making jelly with sugar at 20 cents a pound, but I sweetened the mince meat with molasses to pay for it." [43]

The Bowens liked to entertain, often having guests (including "strangers" just "passing through") for dinner, supper, or tea. [44] When an impromptu dance was held for the garrison, a hospital tent was set up, some of the young soldiers furnished the music, and Katie and her close friends provided food, including ham, biscuits, cakes, and coffee. Although there were seven officers' wives at the post, only Katie, Charlotte Sibley, and Mrs. Alexander prepared the food. Some of the single men had ordered peaches and grapes that arrived the same day from El Paso and provided these for everyone to enjoy. Katie "played matron in the way of presiding at the supper table pouring coffee, etc." The first dance held at Fort Union "went off well and everybody seemed delighted." [45] A dance was one of the few occasions where officers and enlisted men enjoyed some social contact while off duty.

Life was not especially easy in tents at an isolated outpost, but Katie made the best of it. The first time they attempted to wash clothes they found that their stove, standing in the open, would not "draw quite well enough to keep a hot fire." They cooked on an open fire and had erected a bower under which they ate unless it was raining. Katie was sewing drawers and night shirts for her husband and "a winter house dress of the calico" for herself. She spent time socializing with her neighbors and declared, "I am not going to worry myself about work, but live easy and go back to the states as good as new. I am as well off as my neighbors and I have no ambition to shine in New Mexico." [46] She must not have wasted much time, nevertheless, for she wrote not quite two weeks later that "I have been very busy, have got our servants winter clothes all made and nearly all of Isaacs sewing done and this week I am going to alter my cashmere double gown." [47] In one of her few observations about the New Mexican people, Katie observed that "the Mexican women at Vegas 25 miles distant, sew beautifully and cover their own clothes with embroidery, but I am not going into that kind of extravagance." [48]

The officers' wives enjoyed maintaining a degree of fashion, even while living in tents at a remote location. "All the ladies wear woolen double gowns till 11 o'clock and then come out in bareges [49] or some other gossamer thing." [50] Another time Katie observed that "all the ladies here dress very prettily and from outward appearance you would not imagine we were so far from fashion and civilization." [51]

Katie sometimes wrote about what was going on at the post, commenting on the progress of construction of quarters and other buildings as well as other developments. "The head farmer here is cutting hay for winter use but has not more than 30 tons as yet and there are 900 head of cattle, besides several hundred horses and mules to winter." [52] She also relayed the sad story of how Major Philip R. Thompson, while intoxicated, had shot a man at Barclay's Fort. Thompson was arrested and, if the victim died, would be turned over to civil authorities. Katie felt sorry for Mrs. Thompson, who was staying at Barclay's Fort. [53] Major George A. H. Blake, who was camped about three miles from Barclay's Fort, investigated the incident and placed Thompson under arrest. He referred the matter to Colonel Sumner for a decision. [54] The man Thompson shot at Barclay's Fort survived, and Thompson was ordered to pay him $600 damages and join the temperance society in Santa Fe. Katie Bowen reported that the officer "broke the pledge so soon that the society expelled him." [55] Thompson continued to battle with liquor and was frequently unable to perform his assignments. He was eventually cashiered from the service, after appearing intoxicated at a court-martial, on September 4, 1855. He died June 24, 1857. [56]

For the most part, however, existence at Fort Union was fairly routine. Life in the tents at Fort Union was less comfortable on October 11, 1851, when, as Isaac Bowen wrote to his father, "we awoke this morning and found the ground covered with snow and the storm still raging with considerable violence." Both he and Katie had been sick with colds, chills, and fevers. Unlike his optimistic wife who seemed to find good in whatever life brought to her, Isaac expressed his opinion of their situation differently: "I wish we were to accompany the train [soon to leave] to the states, for if ever there was a country which our creator had deserted, forsaken and left to its own means of salvation, that country must be New Mexico." Again, he rationalized their situation: "However, we anticipated but little pleasure, enjoyment or comfort during our residence here, but that little may be less than we anticipated." [57]

Both Isaac and Katie were in better spirits by the end of October, when they were out of the tents and enjoying their new quarters, escaping "the constant dust if nothing more." Katie declared the unfinished rooms "vastly preferable to tents." She proclaimed that "our rooms are very tidy and comfortable having large stone fireplaces that give us genial warmth and cheerfulness." [58] She had a carpet on the floor, "made up by a dragoon tailor," and felt "quite settled." She also gloated that "Mrs. Sibley's and our house fronts the south and we have the bright sunshine nearly all day and we are vain enough to think that our rooms are pleasanter than the other ladies'." To her parents, she wished: "How I would like that you could look in and see how primitive we are in our log houses white washed—logs overhead, chinked and covered with earth to shed snow and rain." [59] By the end of November the Bowens had their third room finished, which served as their bedroom, and Isaac had completed a barn and chicken coop and was working on "other out door conveniences." [60]

The Bowens, and presumably the other residents at the small post, felt quite secure at Fort Union. Katie never thought about Indians and had not heard of any in the area. [61] "Mexicans," she wrote, "only come in with donkey loads of vegetables and fruits for sale and we are so quiet that no sentinels are posted except over the provision and clothing tents." Regarding their own household, Katie stated, "Our big dog takes care that no cattle come about the house, and they are the only nuisance we are likely to dread." [62]

Naturally, in a time when diseases and accidents claimed the lives of people of all ages, Katie Bowen was concerned about medical care. Isaac was injured when his horse fell and rolled over him at the end of October 1851. Katie, in her seventh month of pregnancy, reported in the same letter telling of Isaac's accident that "I have escaped all ills and never felt better in my life." Even though there were military surgeons at the post, she was also prepared to deal with illness. "I have," she wrote, "one chest full of jellies, cordials, roots and materials of every descriptions to make gruels and refreshment for the sick, if we should be so." In addition, Major Francis A. Cunningham, department paymaster, "sent me three bottles of old London brown stout the other day. I would not have a cork drawn but went immediately and locked it up in my chest, not forgetting how much good it did me when I was at home and the time may come when I will need it again. If so, it will be on hand." [63]

Katie fretted about other things besides health. Captain Bowen, in charge of the commissary of subsistence for the entire department and required to purchase large quantities of foodstuffs, was responsible for "considerable sums of public money." Isaac, as did other such officers in Department of New Mexico where there were no places of security before safes were provided, kept the funds under their bed. Katie was not happy about this, especially when Isaac was sent away from the post, and worried in her own amusing way that she might "spend it all for onions." [64] Later she noted that Captain Sibley was away on an inspection tour and that Isaac had the quartermaster funds ($110,000.00) as well as the commissary funds (amount not given). The quartermaster funds, all silver in boxes, occupied a space four feet by four feet by four feet in the corner of the Bowen's bedroom. [65]

Despite such responsibilities, the Bowens made the best of life at Fort Union. They not only had to deal with conditions at the post but with an earlier tragedy as well, the death of their daughter. Katie wrote little about this until early November 1851: "Yesterday was Isaac's birthday and although a sad anniversary in one particular, I tried to make it cheerful for him, but he was gloomy all day. Tomorrow will be a year since we last saw our darling baby." [66] The cause of death and the age of their daughter when she died have not been determined. The Bowens had been married for five years, so the child could have been an infant or several years old. Katie was not a person to dwell on misfortune, however, and continued with her sprightly attitude, looking forward to the birth of their next child and enjoying her friends at the post.

On Christmas Day 1851, according the Katie, "Isaac gave a dinner to everybody [meaning the officers and their wives] at the post." It was a beautiful day, "mild, no snow and plenty of sunshine." Katie reported that the 16 guests at their table as well as all the help in the kitchen "had a nice time and an excellent dinner, a roast of pig, a saddle of venison a month old, . . . a fillet of veal, cold roast fowls with jellies, and all the fixins." They finished the first Christmas dinner celebrated at Fort Union with coffee and fruit cakes baked by Katie. [67]

The good times of the season at the new post were interrupted on December 31 by quite a serious accident" involving two of the children of the commander of the ordnance depot at Fort Union. The boys, Frank (age eight, a mute) and Samuel (age six), sons of Captain and Mrs. Shoemaker, were riding on a load of hay. Somehow, when the teamster was off the wagon, the mules ran away and threw the boys from the load. Frank "was cut badly on the back of the head and had his front teeth broken." Samuel had what appeared to be internal injuries, and both surgeons at the post worked to save his life. [68] Fortunately both boys recovered.

On the last day of 1851 Colonel Sumner returned to Fort Union from his tour of the department, and there was a big celebration on January 1, 1852. Sumner "brought a crate of quinces from the lower country," and gave some to each of the officers' wives. Katie got seven pounds. She described the events of the day as follows: "The companies had a review this morning and after it, the gentlemen were invited to lunch at Col. Alexanders, afterwards they called upon all the ladies." The Bowens received New Year's guests "with a tureen full of egg-nog and some nice cake," plus some apples which had just arrived from the states. On the evening of January 1, 1852, the Bowens were evening guests of the Alexanders, where they "played whist [a card game similar to bridge] and ate ice cream." [69]

Because Katie was nearing the time for delivery of their baby, Isaac wanted to be present. He had been assigned to court-martial duty at Galisteo, where some of the dragoons had established a grazing camp for the horses, but Captain Sibley offered to go in his place because he had to go to Santa Fe anyway. Katie was attended by Surgeon McDougal and a midwife, Dr. McDougal's "housekeeper who has had a large family and . . . [is] considered an excellent nurse." [70]

On January 6, 1852, Katie "made out a few mince pies and boiled custard for company that dined with us at 4 o'clock." At 1:00 a.m. that night she delivered a son they named William Cary, after her father. He was the first child born at Fort Union. The wife of one of the civilian mechanics at the post, a woman who "came across the plains with us," stayed with Katie for almost three weeks, "taking excellent care of baby." When baby Cary was a month old, Isaac had to leave to accompany Colonel Sumner to Albuquerque and then inspect the commissary department at the various posts in the territory. [71]

Although her husband would be gone, Katie assured her parents she was all right. "I am very well fixed. Our servant is a host in herself and will sleep on the floor to keep fires for me. Mr. Martin will sleep in the parlor." In addition, someone was looking after their cows and other livestock "and the prisoners supply us with wood, so I think I am very well cared for." She rejected an offer from Sophia Carleton to live together while both their husbands were away from the post on duties. "I prefer to take my chances alone," Katie declared, "rather than enter into partnership with any one except my husband. She [Mrs. Carleton] has a child and an ugly slave and I will not allow our girl to associate with the black." As a final word of assurance, Katie admonished, "Do not feel anxious for me. I shall get on well and will take good care of myself." [72]

Katie did manage well while Isaac was on his inspection tour of the department, but she was not happy that he had to be away so long. She blamed Colonel Sumner, for whom she already held some enmity. "Nobody but Col. Sumner sees the necessity of inspecting supplies at these outposts, as every pound of provisions goes through the commissary's hands at this post, and forwarded on, so of course all the statements are here, but Col S likes to see everybody on a move and as uncomfortable as possible." In another of her rare comments about the people of the territory, she reported that "Isaac writes that the Mexicans are very hospitable." [73]

Regarding her own situation while Isaac was away, Katie assured her parents, "I have no trouble in his absence. All the out of door work is done by the police party and a man in Isaacs department takes care of the horse, cows, pigs and chickens. The dog oversees the whole and watches at night." The baby was healthy and growing, "hearty and strong as a young antelope." There were soon to be more babies at Fort Union. "Mrs. Carleton, Mrs. Shoemaker and Mrs Sibley are to add to our society in a little while. Surely this is a growing country." [74]

Isaac returned on the evening of April 1, having completed his tour to the satisfaction of Colonel Sumner. He brought Katie several items made of silver from the mines south of New Mexico, including mugs, plates, glasses, and other table pieces weighing a total of six pounds. The price was $1.25 per ounce. He also brought her "some Monterey chocolate," a peck of pinon nuts, and some wine. Although he had only been home one day, Isaac "must be in the office till 11 o'clock tonight in order to finish up his accounts to send them off." He truly took his responsibilities seriously. "He has a most faithful clerk," Katie explained, "but never trusts money accounts to be sent unless he goes over every figure himself." [75]

Major and Mrs. Alexander left Fort Union to return to the states late in April. They had spent three years in New Mexico, and Major Alexander was taking a six-month leave before joining his regiment in Texas. Katie said of Mrs. Alexander, "we ladies will miss her exceedingly for she is ever ready to lend a hand at anything if there is fun going on none is merrier than herself, but if her friends are sick, she is the first one to be on the spot." Although the Alexanders had hoped to join a military patrol on the Santa Fe Trail for protection across the plains, their first opportunity to travel with a group was to join a "Mexican merchant train that is going to Independence for goods." Katie sent her letter with them, noting that "they will go very rapidly as the train is empty." [76]

Captain Carleton became the post commander on April 22, 1852, when the Alexanders departed. As troops from the garrison at Fort Union were assigned to other posts or on detached duties away from the fort during the spring and summer of 1852, [77] Carleton became concerned about fulfilling the many duties of the "depot-post." Early in August 1852 he requested that Colonel Sumner send more troops to Fort Union to assure that the following assignments were done: loading and unloading wagon trains of stores; piling, packing, and overhauling stores at the depot; blacksmith work for needed repairs; carpenters to roof and finish the buildings at the post; burning lime for plaster; herding mules and cattle; employment at the farm on the Ocate; cutting and stacking hay; hospital steward, cook, and attendant; tending the post garden; hauling corn; cutting and hauling sawlogs and firewood; keeping the sawmill running; and standing guard (a larger guard was needed to protect the many commodities stored outside of buildings). [78] It was a long list, and Carleton was leaving the following day with a patrol to the Arkansas, reducing the garrison even further. While he was away, Captain William T. H. Brooks, Third Infantry, served as post commander. The garrison was increased to an aggregate of 238 in September, with the addition of Company D, Third Infantry, on September 5, under command of Second Lieutenant Joseph E. Maxwell. [79]

The size of the garrison was of little concern to Katie Bowen, who was feeling good in the spring of 1852 because her husband was home again and their young son was doing well. She described herself as "very happy" and wrote of baby Cary that "a better child never lived." She was proud of their economic well-being, too, praising Isaac for his skills. "We have forty-seven chickens, three little porkers and a calf, beside the large stock and never were living more comfortably." [80] The Bowens had adapted well to their station at Fort Union.

Late in May 1852 Captain Bowen was assigned the task of transporting $40,000 of silver specie from the family bedroom to the paymaster at Santa Fe. Mrs. Bowen was concerned about his safety, noting that he would camp overnight at "Old Pecos church." Then, "if nothing happens to him," he would reach Santa Fe the next day and return home two days later. She admitted, "I am sorry to have him travel about the country with a small escort." She never indicated who she thought might attempt to rob him but, the underlying implication was that it was not safe to travel in New Mexico without sufficient protection. [81]

There was an element of mistrust and disdain in her attitude toward New Mexicans. She made it clear, when it came time for baby Cary to be vaccinated for smallpox, "I would not let the Doct put in any matter till he told me that it was from the arm of a healthy American child, belonging to a clergyman's wife in Santa Fe." After the first vaccination showed no sign of taking effect after several days, Cary was vaccinated a second time. Then both of the inoculations "took" and he was a sick child for several days. [82] Because she had lost one child, Katie was much concerned about the health of her son. She was convinced that catnip was "a medicine for all baby ailings" and planted some in her herb garden. She also requested some catnip be sent to her, in case "the seed does not grow," to make sure she always had a supply on hand. [83]

The Bowens continued to entertain at their home. Early in July 1852 Katie wrote, "I cannot write much to you by this mail as the military train, ladies, officers and recruits came in on Tuesday and every day we have had a table full and I must of course do most of the cooking." She observed that the officers were restricted to 250 pounds baggage on this trip, while she and Isaac had brought 2,000 pounds when they came the previous year. Her explanation was that "every year some mean law is passed to the discomfort of the army." An important event at the post was the opening of the ice house on July 1, making it possible "to treat our friends to cool water, butter and cream." Katie was planning to make ice cream to serve the next day, when she intended to open a jar of strawberries she had brought from home a year earlier. [84]

While everything seemed to be satisfactory with the Bowens, Katie was concerned about her close friend, Charlotte Sibley. Neither Charlotte nor her baby seemed to be in good health. "Mrs. Sibley is like a rail and her boy is not at all healthy. The Doct wants her to go home for he says she will die if she stays with the Maj." Charlotte was much younger than her husband, and she was his third wife. Katie did not approve. "I should not think a girl would marry any man who had had two wives, one is bad enough. I am sorry for her and do all I can for her." Katie made no effort to hide her contempt for Sibley. "Maj. Sibley is not a man that can assist a woman at all and will poke about his office all day instead of being at home to relief her of the baby for an hour." [85] Katie's friendship with Charlotte Sibley was soon to pay off, and Charlotte was able to reciprocate for the care she had received from her friend and neighbor.

On September 27, 1852, Katie Bowen tripped in a small drainage ditch outside their home while carrying Willie (the Bowens had stopped calling their son Cary and henceforth referred to him as Willie or, occasionally, Willie Cary). She held onto her son but suffered two fractures of her left leg between her ankle and knee. It was a serious injury, as Isaac described it, "the flesh was considerably lacerated by the sharp edges of the broken bone." It was later discovered that "the ankle suffered a violent sprain and has been, as well as the limb, very much swollen." Post Surgeon John Byrne attended her, and Katie was confined to bed for several weeks. During that time Charlotte Sibley "attended faithfully to Willie, washing, dressing and undressing him every day." [86]

By January 1853 Katie was able to "walk a little about my room" and reported that "the swelling in my limb is gradually disappearing." Isaac was away on his annual inspection tour, but Katie was getting along with the help of others. She had employed a "Mexican" woman after breaking her leg, but stated that "Isaac left for Santa Fe and as a matter of course, my Mexican woman had to follow the men." Her prejudices against New Mexicans came out again as she rationalized, "I am better off than if I had kept the woman." She was sure the woman had been stealing from her, declaring "they all consider stealing fair profit, but are so cunning that they are never found out." She also let go another blast at her favorite nemesis, the department commander. "If anyone asks your opinion of Col. Sumner tell them he is an old fool for because I got hurt and Isaac did not go with him three months ago, he now sends him all alone to punish him." [87]

She communicated this same attitude to Governor Lane, "I gave Col Sumner credit for some kindly feeling, but discover that his 'buzzom' is too contracted to contain one drop of sympathy." Katie's sarcasm continued, "It is manly, in a person wielding power, to punish a husband because the wife is unfortunate." Then, after stating "I heartily despise these annoyances," Katie concluded with a precautionary tone: "My pen is too military and afraid to speak its sentiments for fear of being court-martialed." [88]

On the bright side, Katie reported that Mrs. Sibley had been feeding goat milk to her sickly child, Fred, and "he has got as fat as anybody's baby." Another change occurred with the arrival of the new post commander, Major Gouverneur Morris, and his wife Anna Maria in mid-December 1852. "We are prepared," Katie declared, "to like himself and wife very much." [89] Anna Maria Morris and Katie became friends, but not as close as Katie and Charlotte Sibley. Mrs. Morris kept a diary all the time she was in New Mexico, and her comments while at Fort Union add to the observations of Katie Bowen. Mrs. Morris had a black female servant, probably a slave, named Louisa. Mrs. Morris had no children, but Louisa had an infant son, Carlos. [90] The Morrises' arrival at Fort Union was part of a change in the garrison.

In December 1852 Company G, Third Infantry, was transferred from Fort Union and Company D, Second Artillery, joined the garrison for duty. On December 18 Major Gouverneur Morris, Third Infantry, superseded Captain Carleton as commander of the post. Except for changes of commanding officer (Captain Horace Brooks, Second Artillery, on June 30, 1853, and Captain Nathaniel C. Macrae, Third Infantry, on August 3, 1853), the garrison was comprised of the same units until October of 1853 when Company H, Second Dragoons, replaced Company K, First Dragoons. The size of the garrison averaged 242 officers and men during that time. [91] Major and Mrs. Morris seemingly enjoyed their term of service at the post.

Anna Maria Morris already knew some of the officers' wives at Fort Union, but she apparently met Katie Bowen for the first time a few days after her arrival. Because Katie was confined with her broken leg and sprained ankle and because Isaac was away on tour, Katie was not able to participate in the welcoming activities for the new commander and his wife. On December 18, the day after Major and Mrs. Morris arrived at Fort Union and the day the major assumed command of the garrison, Mrs. Morris was a guest in the home of E. S. and Charlotte Sibley. Anna Maria noted that Caroline Shoemaker visited her during the day. The only comment Mrs. Morris had about Fort Union was the "very high wind." She visited Katie Bowen on Christmas Day. [92]

Major Morris was ill on December 30, 1852, but Anna Maria was a supper guest and enjoyed a party at the Shoemakers' home that evening. The major attended muster the following day, although he was still quite sick. Mrs. Morris reported that, on January 1, 1853, "the officers & ladies called during the day." She received some gifts, including a ring from Dr. Byrne and a pair of gloves from Charlotte Sibley. Dr. Byrne "passed the evening with us, the Maj is confined to his bed." [93] Major Morris was soon able to be back to work, but Anna Maria became ill later in the month. There was no clue in her diary as to what either of them may have been suffering.

Anna Maria Morris mentioned Katie Bowen a number of times and provided as much information about the latter's recovery as Katie did herself. On January 5 Anna Maria "called on Mrs. Bowen who is still confined to her bed with her broken limb." The next afternoon she "met Mrs. Bowen at Mrs. Sibleys the first time she has been out since her accident." On January 21 Anna Maria visited Charlotte Sibley in the morning and "passed the afternoon with her & Mrs. Bowen." The next day she recorded that "Capt. Bowen returned." Just two days later "I called at Mrs. Bowens found her preparing for a party the next evening." On January 25, "went to the party at Mrs. B's in the eve and enjoyed it very much." [94]

By January 27 Anna Maria was "not at all well" and two days later was "sick in my room." She called Dr. Byrne to see her again on January 31 and recorded that she "was pretty well the rest of the day" and "all the ladies called." After feeling "pretty sick" again on February 3, Anna Maria recovered. She "passed the afternoon" of February 7 with Katie and Charlotte and they "passed the afternoon" with her on February 9. Clearly Anna Maria Morris had taken her place in the small circle of close friends among the officers' wives, and Katie Bowen was improving in health. [95]

By the end of January Katie reported that she was able to "walk about a good deal although the limb swells always when I bear my weight upon it." She was "living again according to my desire" because Isaac had returned from his tour of inspection. "I go out every warm day with the Capt. in the carriage and the rest of the time sew or read." [96]

Anna Maria Morris kept a summary record of what was happening among the members of her class at Fort Union while she was there. On Monday, February 14, Captain Shoemaker, Lieutenant Sykes, and Surgeon Byrne went to Las Vegas to "shoot ducks." They returned two days later and gave some ducks to the Morrises. That same afternoon Major Morris and his wife went for a ride. On Thursday, February 17, Anna Maria was "busy all day." She hosted a party that evening and "they danced till 1 O'cl." [97]

By this time, after being in New Mexico for over three years, Anna Maria's diary entries were terse. On Monday, February 21, she wrote: "Col. Sumner arrived took tea with us, after tea the mail arrived." February 22: "Col. S. breakfasted with us dined at Maj Carletons. I passed the morning with Mrs Sibley & Bowen in the afternoon I made a pair of under sleeves. Capt Sykes was arrested in the morning." [98] She provided no clue as to why Lieutenant (Brevet Captain) Sykes was arrested, but it was because he had punished improperly two prostitutes who were plying their trade at the post. The complete story of the arrest and court-martial of Sykes is found in chapter ten.

Despite her sparse notations, Anna Maria Morris gave some flesh to what was an otherwise meager skeletal outline of life at the post. February 24: "Col Sumner & the Maj were invited to Maj Carletons to play whist. I passed the evening with Mrs. Sibley." During that afternoon Major Morris had taken his wife, Katie Bowen, and Charlotte Sibley for a "ride." February 25: "Col. Sumner breakfasted with us and then went to the farm at Ocate. Mrs. Shoemaker called in the morning & Lt Maxwell [and] Dr. Byrne after dinner." February 26: "Col. Sumner returned took tea with us and in the evening we played whist. Maj Carleton passed the evening with us." Sunday, February 27: "Inspection & drill, a very windy dusty day. The Col. dined at Maj Carletons [and] took tea with us." February 28: "Muster day. Dr Byrne called. Col Sumner the Maj & I took tea & passed the evening at Capt Shoemakers." [99]

On March 1 Colonel Sumner ate breakfast and dinner with Major and Mrs. Morris "and then took his departure for Albuquerque." Their supper guests included Jared W. Folger (post sutler and postmaster), Ceran St. Vrain (former partner in Bent, St. Vrain & Co. that built and operated Bent's Fort and now a miller, trader, army contractor, and sometime colonel of New Mexico volunteers), "Mr. Hubble" (perhaps Santiago L. Hubbell, a New Mexican trader who operated wagon trains over the Santa Fe Trail), Captain Peter Valentine Hagner (ordnance department, who was on his way to Fort Massachusetts), and "Mr. Cassin" (who was accompanying Captain Hagner to Fort Massachusetts). They were all joined in the evening by Dr. Byrne and Captain and Mrs. Shoemaker. The following day Dr. Byrne came by to invite Captain Hagner and Mr. Cassin "to dine at the Mess the next day." [100]

On March 4 "the Maj started on his journey to Taos at 10 O'cl. Maj Hagner & Mr Cassin left for Fort Massachusetts an hour after. Caroline Shoemaker called. I took a siesta after dinner." Sunday, March 6, was "a fine day. . . . I took a siesta after dinner. When I got up I found the old hog had eaten up five of my little chickens." [101]

While her husband was gone, Anna Maria Morris spent a portion of her time reading James Fenimore Cooper's The Spy, a patriotic novel about the American Revolution. [102]. This was one the few times that someone at Fort Union identified a book being read. When Major Morris returned from Taos on March 14, he came "with the mules well loaded with vegetables." [103] Anna Maria Morris usually said little about food at Fort Union, while Katie Bowen mentioned it often.

According to Katie, a second ice house was constructed at the post before winter commenced, and both were "filled to the top with ice" by early March "which gives us a prospect for cool butter next summer." [104] Katie frequently wrote about food, was proud of the variety and quality of what her family had to eat, and summarized the menu she served for a few friends late in March. "Our dinner consisted of roast pig (the whole hog or none) and baked potatoes, [105] Mexican beans and macaroni with pickles and bread and butter—for dessert the last of my mince pies—boiled custard and preserved cherries and cheese." She and Isaac had concluded that they truly liked being stationed at Fort Union, "where we can live on our pay and have good health." They feared being "stationed in some unhealthy city." [106]

Fort Union still had no chaplain, which seemed not to matter to Katie. She reported that "Sundays here are very like any other day. We have no service to attend but can read our good books in peace here as in any other country." The surgeon, however, was a more important officer in her life and in the lives of the rest of the garrison. [107] Anna Maria Morris confirmed this, for her diary was filled with references to the post surgeon. She noted on March 20 that the surgeon reported the "narrow escape" that Ebenezer, Charlotte, and Fred Sibley had experienced while out riding. The mules became frightened and ran away with the ambulance, which upset. Although no one was seriously injured, Mrs. Sibley was "much frightened" and worried about little Fred. The next day Anna Maria noted that Charlotte Sibley "is a little injured by the upset." [108] Dr. Bryne was in contact almost daily with the officers and their families, and both Anna Maria and Katie noted that Dr. Byrne was absent on court duty early in April, serving at the trial of Lieutenant Sykes. Dr. O. W. Blanchard, a contract physician from Wisconsin, took his place at Fort Union. [109]

Everything was quiet for several weeks; according to Katie Bowen "there is nothing going on." [110] Anna Maria Morris spent some of her time reading another Cooper novel, The Pilot, an adventure story on the high seas. She also made some clothes for Louisa and her son, Carlos, and did some sewing for herself. Major Morris spent some time fishing, but what luck he had was not recorded. [111]

There was some excitement at the post on April 14, when it was discovered that the hospital storeroom had been robbed of eight cases of wine. Major Morris rode out "to see if he could find it in a train that left for Albuquerque" early that morning. Unfortunately, the saddle girth broke and the major was dumped from his horse. Somehow the horse stepped on Morris's leg and "hurt him very much." He soon recovered but the wine was not found. He and Anna Maria went fishing a few days later at "Coyote seven miles" and "caught a good bit of fish." [112]

Social activities picked up in the spring of the year. On May 4, according to Anna Maria Morris, "we had a very pleasant little dancing party at the adjutants offices to which the ladies all contributed we had a nice supper." A number of officers and their families were gathering at Fort Union in preparation for a trip to the States, and this added to the visiting going on there. A winter storm, including snow, interrupted the spring weather on May 7, but spring returned quickly and Mrs. Morris picked her first bouquet of flowers the next day. [113] Regarding the departure of officers from New Mexico, Sophia Carleton informed Governor Lane, "Our garrison is becoming dull as can be. Every body leaving and no one coming." [114]

Anna Maria Morris seldom mentioned military affairs, but on May 9 she recorded that Colonel Sumner had sent an express from Fort Massachusetts, directing Major Morris to hold all troops at Fort Union in readiness to march at an hour's notice. Sumner expected some difficulty at El Paso with troops from Mexico. The anticipated trouble did not occur. Except for "a very high wind and dust blowing in every direction," things remained quiet at Fort Union. Major Morris spent much of his spare time fishing, often with good results. He also made a trip to the post farm at Ocate. He returned to find that two of his mules were gone and spent several days looking for them, without success. A few days later the mules were caught by a civilian near Las Vegas, who notified Major Morris, and two men were sent to retrieve them. [115]

On June 6, 1853, Charlotte Sibley delivered another baby boy, named Henry Saxton. The new child seemed to be healthy, but Fred Sibley still had problems and was often sick. [116] Although Charlotte and E. B. Sibley thought little Fred was "splendid," Katie Bowen observed that "he has a big head that looks to me very much like rickets and hangs to one side as though it was too heavy to carry." Never one to hide her opinions, Katie declared that Charlotte, "if she keeps on . . . will lead a slaves life instead of being an old man's darling, as the saying goes." Captain Sibley was 47 years old the day the new baby was born, an old man in Katie's view. Of the new Sibley child, on whom she "served first apprenticeship to dressing a new born baby," Katie asserted "it is mortal ugly." Charlotte "says she is not going to have another baby till next year." [117]

Major Morris was awaiting orders to relieve him of command at Fort Union and grant him a leave of absence. As soon as possible, he and Anna Maria planned to travel to the states. Mrs. Morris was disappointed on June 7 that they were not yet able to leave. "A Mexican train," she wrote, "started from Barclays Ft this morning. A number of discharged soldiers went with it and we have lost a first rate opportunity of going in as they had plenty of transportation." She was enlivened a few days later with the arrival of several officers from the East, coming to serve in New Mexico, and was pleased "to hear all the news they brought." On June 22, Anna Maria recorded: "The flag at half mast today and salutes being fired for the death of Mr. W. Rufus King late Vice President of the U.S." [118] Vice-President King had died on April 18, 1853, and it had taken over nine weeks for the news to reach Fort Union.

Major Morris received his awaited orders to leave New Mexico on June 24, and the about 25 discharged soldiers. They traveled quickly and without difficulty, arriving at Fort Leavenworth on July 22, 1853. [119]

With the departure of Anna Maria Morris, Katie Bowen again was the primary source of information about life at Fort Union. Katie's broken leg was still mending in early July, and she noted that her ankle "gains strength every day." She was able to wear a boot on the disabled limb and was becoming more mobile. She and Willie had accompanied Isaac on a trip to Tecolote in June 1853. "The mountain scenery was fine and we enjoyed the drive very much." Because of the drought, which was destroying the gardens and drying up the irrigation ponds at Fort Union, Katie witnessed some additional aspects of New Mexican culture (which she neither understood nor approved). [120]

At Tecolote "the Mexicans were parading their saint through the streets (erected upon a kind of bier) to the music of fiddles, drums, singing and pop guns, imploring the divine giver of all things to send them rain before they famished." To Katie, who believed in her own cultural superiority, "it was a ridiculous sight but no one could have the heart to laugh at what they deem religion." After seeing Las Vegas and Tecolote, Katie commented that "Mexican towns very much resemble large brick yards tho not as good looking as the one near our Arsenal." On the return trip she was appalled to see "the Mexican population, men, women and children . . . celebrating St. John's day by riding yelling and pulling live chickens to pieces like so many devils." In addition, "there were many fine horses run to death that day and the women were as bad as the men." Katie enjoyed the land of New Mexico but was disparaging about the people. [121]

The drought was broken during July, with the advent of the rainy season. According to Katie, "some heavy rains that have fallen lately injured the garden very much but improved the grass." The arrival of the new department commander, Brigadier General John Garland, was considered an improvement by the Bowens, and they were assured by Garland that they would remain stationed at Fort Union for the time being. Katie wrote that "it affords us great pleasure to remain." [122] They also were pleased with the new post commander, Captain Nathaniel C. Macrae, who brought his wife, two daughters, and a piano across the plains. Katie was glad to see another woman at the post, for E. B. and Charlotte Sibley, and their two sons, soon left Fort Union to return to the states. Katie would miss Charlotte Sibley, but she expressed sorrow for that poor woman even as they departed. "Mrs. Sibley got started at last . . . and such another mess as they went in, you never saw. Nothing packed - nothing in order - and everything thrown together in a hurry." She wondered if they would make it. "To be a quartermaster and go as the Sibleys did - I would not expect to live till we reached half way." [123]

When General Garland arrived at Fort Union from Fort Leavenworth on July 31, 1851, he was accompanied by Colonel Mansfield, inspector general for the department, who was under orders to conduct a thorough examination of all the posts in New Mexico Territory. The day after he arrived at Fort Union, Mansfield began his investigation of the department, spending six days probing into Fort Union, including the quartermaster and commissary depot, medical depot, ordnance depot, and the farm at Ocate. It was the primary inspection of the post since it was constructed, and his report and accompanying map provided an informative but uncritical overview of the first Fort Union. Perhaps, because this was his first inspection duty in New Mexico, Mansfield was positive about almost everything he observed. As he proceeded through the rest of the department, he became more critical in his judgment of conditions and of Sumner. During the course of the inspection at Fort Union the command of the post changed when Captain Macrae, Third Infantry, replaced Captain Brooks, Second Artillery, on August 3. [124]

Mansfield had nothing but praise for the troops at Fort Union, declaring that the garrison was "in a high state of discipline and every department of it in good order." All companies, artillery, infantry, and dragoons, were "in excellent efficient order." Their clothing and equipment were worn but "serviceable." All the soldiers were "well instructed in drill." Mansfield recognized that this was not an easy task at a frontier post. "Much credit," he wrote, "is due to these officers, . . . when it is taken into consideration that the labour of building quarters, getting timber, wood, hay, farming, escorting trains, and pursuing Indians is all performed" by the same troops. The officers, too, faced a difficult task when only one officer per company was present. [125]

The inspector said little about the buildings at Fort Union, but remarked that the company quarters "were in a good state of police, and the comfort of the troops studied in all the details." The men were "well fed" and "there is a good post bakery here." There was an adequate supply of clothing except for shoes. The hospital was "comfortable." The dragoon horses were "well provided with safe and good accomodation." In all Mansfield presented a positive image of the post and its occupants. He noted however that the troops had not been paid for five months and saw "no good reason for so much delay." He also observed that "this is a Chaplain Post, but the Council of Administration have not succeeded in getting a Chaplain to conform to their peculiar views." [126]

The quartermaster depot, under Captain Sibley since the post was founded, was declared to be in the competent hands of "an officer of distinguished merit." The storehouses are as good as circumstances would admit." The property for which Sibley was responsible "is in a good state of preservation, and the corrals and stables for public animals, suitable and secure." The supplies for the whole department were delivered to Fort Union from Fort Leavenworth by contract freighters, "a very good arrangement and the cheapest for the Government." Mansfield did not explain how supplies were distributed to the other posts in the department. There was "an excellent mule power circular saw mill which supplies all the boards, planks, and scantling required." Considering all the complaints recorded about the sawmill, Mansfield must have appeared at a fortuitous time. [127] Within a few days after Mansfield inspection, Sibley was replaced as departmental quartermaster by Captain Langdon C. Easton, whom Sibley had relieved of that same office two years earlier, and Sibley departed for the states. [128]

Although Sumner had fired most civilian employees when he arrived in the department two years earlier, Mansfield found 28 citizens working at the depot, including a clerk, carpenter, wagon master, forage master, principal teamster, saddler, and 23 teamsters and herders. In addition 39 soldiers were employed on extra-duty for 18 cents per day. They were performing such tasks as artificer, carpenter, blacksmith, wheelwright, sawyer, hay cutter, and other unspecified jobs. Mansfield encouraged the use of soldiers in this manner, although he suggested that they be rotated often "to give all the men an opportunity and to keep them well instructed in their military duties proper." [129]

The commissary department, under Captain Bowen, "is well conducted by him." An adequate supply of everything was in the storehouse except for rice and coffee. Coffee was being borrowed from the post sutler until a new shipment arrived. Bowen had ordered enough, but his order had been "cut down." Flour was obtained by contract from Ceran St. Vrain's mills at Mora and Taos Valley. Beans and salt were purchased locally. Beef cattle were driven from Missouri and some were obtained in New Mexico. There was at the post "an excellent slaughter house." The system of distribution to the other posts was not explained. Colonel Sumner's farming experiment, carried out under orders from the war department, had affected the commissary accounts. "The farming interest in this Territory is represented to be 14,460.08 dollars in debt." [130]

The medical depot was supplied with everything required. Because Assistant Surgeon John Byrne was on detached service, a civilian physician, Dr. O. W. Blanchard, was temporarily in charge of the depot and the post hospital. There were seventeen men on the sick list when Mansfield visited the post, and he reported they were "well cared for in hospital." The system of distribution of medical supplies to other posts was not mentioned. [131] Mansfield made no mention of the need for an ambulance, but someone had the idea. On August 23 Garland directed Easton to "purchase a suitable ambulance for the accommodation of the sick, and for the transportation of Officers under orders, from one post to another within the limits of this Department." [132]

Military Storekeeper William R. Shoemaker was in charge of the ordnance depot "for the whole Territory." The supply of ordnance and ordnance stores was found "ample under the present aspect of affairs, and all in good order and state of preservation." The quarters and storehouses were considered "sufficient," and a new gun shed was under construction. The depot employed one civilian armorer and twelve extra-duty enlisted men, some of whom were cutting hay and others were building the gun shed. Mansfield recommended that the employees of the ordnance depot should be repairing arms and making cartridges. [133]