|

Fort Union

Historic Resource Study |

|

CHAPTER SEVEN:

THE THIRD FORT UNION: CONSTRUCTION AND MILITARY OPERATIONS, PART TWO (1869-1891)

The third Fort Union, despite efforts to diminish or phase out its missions, remained active over two more decades. The recommendations of General Sheridan and Adjutant General Townsend did not go unchallenged. District Commander Getty held a different view of the situation. In his report on the District of New Mexico in October 1869, Getty (who, unlike Sheridan, had seen the post), provided a brief overview of the facilities at Fort Union. In addition to the supply depots and arsenal, he noted that Fort Union's "commodious buildings, stables &c, and the good quality and cheapness of forage renders it a good cavalry post, and one where cavalry can be schooled and drilled, the horses well cared for and yet be available in cases of emergency." The potential for emergencies in the district was considerable. Getty observed that, "with 30,000 Indians in or near the District and a native population very hostile to them, and continually giving rise to quarrels, it is obvious, that a permanent military force is necessary in the Territory." He also declared that, "in case of a general outbreak among the Indians in northern New Mexico," Fort Union "would be of great importance." [1] Whatever its importance, or lack thereof, Fort Union had not yet reached the half-way point of its years as an active post. Thus, recommendations for improvements, such as those offered by Lieutenant Colonel Davis, were important to its future.

Before a system of water distribution was installed, a fire in the family quarters of the depot commissary (designated as No. 2 Depot), Captain Andrew Kennedy Long, on November 15, 1871, damaged three of the eight rooms, a portion of the hall, and the veranda. The cause of the fire could not be determined but arson was suspected. The damage was estimated at $1,100. [2] This was not a major loss, but it likely spurred responsible officers to proceed with plans for a water system at the post, which was installed a few years later.

By 1870 the practicality of tin roofs was seriously in question. Post Surgeon Peters observed that tin roofs, "in this climate, do not answer for the reason that where artillery is used, the firing springs the nails and solder, and severs the attachments." In addition, "the adobe settles and causes the tin also to loosen. The tin rusts; the high winds detach it, and in every respect it is more expensive and less serviceable than shingles." [3] The post commander, Colonel John Irvin Gregg, Eighth Cavalry, explained the situation to the depot quartermaster, Captain Andrew Jackson McGonnigle, as follows: "Some of the roofs have been painted, but the paint blisters, and owing to the settling of the walls of the buildings, the soldering is broken in places on the roofs." Gregg concluded, "the consequence is that all the roofs leak more or less, and the plastering scales off from the ceilings, and to such an extent, as to render the occupation of Quarters unsafe." [4]

McGonnigle immediately requested permission from the district quartermaster at Santa Fe, Captain Augustus Gilman Robinson, to purchase some Tascott's enamel paint "for trial on the roofs of the public buildings at this Depot and Post." This paint was advertised to form "a perfectly Water-proof Covering," be "unaffected by changes in temperature," be "superior" for "roof paint," and "will not crack, peel, blister or chalk off." The paint could be purchased for $1.80 per gallon. [5] Despite the claims, the paint did not solve the problems of leaking roofs at Fort Union, which became more of a problem each year. A tinsmith was required almost constantly to repair the solder joints of the tin roofs. The penetration of moisture caused the plaster to crack and fall, requiring frequent repairs by a plasterer. [6]

In 1869 and 1870 the garrison at Fort Union was reduced during the spring and summer months when troops were sent to other places where they were needed to deal with Indians. For example, some of the cavalrymen were sent to Fort Bascom, where field duty was frequent during the warm months, and returned to Fort Union, where provisions for men and horses were more abundant, during the cold season. The small command at Fort Union was kept busy with routine duties and occasional escorts. The outpost was continued at Cimarron, where Lieutenant Ennis, Third Cavalry, died on August 12, 1869, "from injuries received by being thrown from his horse." He was buried at the Fort Union cemetery. [7] Accidents and diseases always claimed more lives of the troops than did warfare.

Among the changes at Fort Union was the transfer of Chaplain Woart to Dakota Territory in August 1869. Post Commander Grier requested that Rev. James Armour Moore La Tourrette be appointed as the new chaplain, "provided the Secretary of War should think it proper to appoint any Chaplain to this Post." Although Grier apparently preferred La Tourrette (since he asked for him), he reported that a majority of the officers at the post preferred Rev. William Vaux. Neither was appointed at the time. Chaplain David W. Eakins arrived at Fort Union on September 5, 1870. He served until granted sick leave on January 17, 1876. Chaplain Eakins died on March 5, 1876, at Philadelphia, Penn. He was followed by Chaplain George Washington Simpson, August 15, 1876, to August 4, 1877, when he was granted sick leave. On September 20, 1877, Rev. La Tourrette arrived. He served as post chaplain until he retired on March 23, 1890, being the chaplain with the longest tenure at Fort Union. John S. Seibold was the last chaplain to serve at the post, arriving August 26, 1890, and departing April 20, 1891. [8]

The westward expansion of the railroad after the Civil War affected the way things were done at Fort Union. Before the Union Pacific Railway, Eastern Division, built westward in Kansas, the annual supply of recruits for the companies in the District of New Mexico were marched from Fort Leavenworth over the Santa Fe Trail each fall, under command of officers who were assigned to or were returning to duty in the territory. In 1869 Post Commander Grier was directed to send two officers from his garrison to the railroad at Sheridan, Kansas, to meet 110 recruits for the Third Cavalry and conduct them back to Fort Union. [9] From that time on, recruits arrived in small numbers throughout the year, since it was no longer necessary to wait for a large number to make the overland trip from Fort Leavenworth feasible.

The railroads also facilitated the shipment of horses to the district. Late in September 1870, Captain Augustus W. Starr, Eight Cavalry, led a detachment of 56 enlisted men, a veterinary surgeon, and a hospital steward, with four army wagons and two ambulances, from Fort Union to the railroad at Kit Carson, Colorado Territory, to receive and return with 200 horses. They encountered bad weather and two horses became sick and unable to travel. They returned to Fort Union with 198 horses on October 20. The horses were turned over to the quartermaster depot. [10] Another 200 horses were received at Kit Carson in September 1871. [11] As the railroads built closer and closer to Fort Union, reaching the nearby community of Watrous (formerly La Junta) in 1879, the transportation of personnel and supplies became faster, cheaper, safer, and more reliable. The coming of the railroad and all that went with it (including expansion of settlements, founding of new towns, economic enterprise, tourism, and the final solution to Indian interference) eventually made the military occupation of New Mexico unnecessary and the third Fort Union a non-essential appendage.

Until that happened, Fort Union continued to contribute to the keeping of the peace in New Mexico. In December 1869 the Moache Utes and Jicarilla Apaches at the Cimarron Agency at Maxwell's Ranch became "unsettled and hostile." This was the result of the department of Indian affairs decision to withhold annuities from these people and plans to place them on a reservation in Colorado Territory. Colonel Grier was directed to send at least 100 cavalrymen to reinforce the outpost at the Cimarron Agency. The troops were instructed "to avoid, if possible, a collision with the Indians." They were to be there, "in the event of hostilities, to be prepared to drive them west of the mountains, and to follow them up promptly." The troops were supplied from Fort Union. Surgeon Longwill was sent from Fort Union to serve as medical officer at Cimarron. [12] Trouble was averted when the annuities were delivered to the Utes and Jicarillas, and they were permitted to remain at the Cimarron Agency. The troops sent from Fort Union returned to the post.

The Third Cavalry was transferred from New Mexico in the spring of 1870. Some companies were sent to Arizona Territory and Nevada, and the others went to Wyoming Territory. The regiment was replaced in New Mexico by the Eighth Cavalry. In May Captain Charles Hobart, Eighth Cavalry, succeeded Colonel Grier as post commander, and the garrison was comprised of two companies of the same regiment. In June Colonel Gregg, Eighth Cavalry, again became post commander. Private Eddie Matthews, Company L, Eighth Cavalry, had recently arrived at Fort Union. He noted that Gregg, "from all accounts is a very fine man to soldier under, he is about seven feet tall." [13] By the end of the year, the garrison included four companies of Eighth Cavalry and one of Fifteenth Infantry. Except for changes in the office of post commander and seasonal variations in the number of troops at the fort, the garrison of Eighth Cavalry and Fifteenth Infantry remained fairly stable for more than five years. [14]

It was typical of most new commanding officers to make changes and correct conditions that had apparently been neglected by their predecessors. Problems that older residents had learned to live with stood out to the newcomer, demanding that something be done. Captain Hobart had not been at Fort Union one week when he reported that the officers' quarters and enlisted mens' barracks were "greatly in need of whitewashing and that the plastering also requires repairing." He was determined to improve conditions but had "no soldiers in my command competent to perform the duties." He therefore requested that the depot quartermaster be directed by the district commander to have the work done by depot employees. [15] The response was not located.

Hobart apparently thought that Fort Union had gone to the dogs and issued an order declaring "no dogs will be allowed to run at large at this Post." The method of enforcement was direct and uncomplicated. "All dogs found loose about the garrison will be killed at once." The sergeant of the guard was responsible for seeing that the order was "strictly enforced." [16] Surely someone at the post mused about who was supposed to inform the dogs. A few weeks later, Surgeon Peters discovered a good reason to enforce the order. A rabid dog was killed at the quartermaster depot. Peters, apparently unaware of Hobart's earlier orders, recommended "that all loose dogs found on the Reservation be killed and orders be given to keep any dog of value chained." [17]

Hobart was not the only commanding officer wanting to make changes. General Pope again became commander of the Department of the Missouri in 1870, and he (in a view similar to that of General Sheridan) recommended, among many other suggested changes in New Mexico, that Fort Union be abandoned and supplies be shipped directly to the posts for which they were intended. That did not set well with District Commander Getty, who wrote a splendid defense of the depots and the post at Fort Union, pointing out that closing them would necessitate a much greater expense in supplying the district. [18] Whether Pope was convinced by Getty's economic arguments or some other reason, Fort Union and the depots survived another proposal to shut them down.

During the summer of 1870 there were reports of attacks by Indians, believed to be Cheyennes and Arapahos, near Fort Bascom. Company F, Eight Cavalry, commanded by Captain Dudley Seward, was sent from Fort Union to strengthen the garrison at Bascom for several months. The mission of these soldiers was "to prevent hostile incursions into this District." The commanding officer at Fort Bascom was directed to keep cavalry scouts "constantly in the field" watching for Indian signs. Pickets were also to be located along the Fort Smith Road, giving protection to travelers if required. [19] Later in the summer, when it was feared there might be trouble with the Utes at the Cimarron Agency, Company D, Eighth Cavalry, commanded by Captain Starr, was transferred from Fort Bascom to Fort Union to increase the garrison there in case of an "emergency" with the Utes. [20]

On August 28, 1870, a scouting party comprised of troops of Company L, Eighth Cavalry, were sent from Fort Union to the Cimarron Agency, where they found, according to Private Matthews, a member of the detachment, "everything quiet." A portion of the company was sent from Cimarron to search for livestock thieves northeast of Cimarron into Colorado Territory. They went to the infamous Stone Ranch, where Samuel Coe had been arrested a few years earlier, expecting to find a new gang of thieves led by a man named Arbuckle. Private Matthews reported that the 30 troopers rode hard to reach Stone Ranch and charged the supposed hideout at dawn "as fast as our horses could carry us." He continued, "Saw the Ranch and made a gallant charge with carbines drawn and loaded. Surrounded and took the Ranch without firing a shot or loosing a man, but on entering the building found it full of emptyness. Not a living thing could we see. . . . So we had to return as empty handed as we come." [21] Matthews was pleased that the troops had not had to fight either Indians or horse thieves and returned safely to Fort Union.

A few weeks later, after additional rumors of troubles between the Utes and Jicarilla Apaches near Cimarron, Company L, Eighth Cavalry, commanded by Captain Hobart, was sent to encamp at the Cimarron Agency until the crisis was resolved. [22] Captain Hobart reported the situation "quiet" when he arrived at Cimarron, and attributed most of the trouble to a few drunken Indians. He suggested that, if the whiskey traders were "caught and punished," there would probably not "be the slightest trouble with the Indians." [23] Private Matthews reported that the log quarters at Cimarron were "in a bad condition" and there was little to do except "to drill twice a day." He noted that a party of recruits arrived at Cimarron on their way to Fort Union, and that one of the new soldiers died of starvation and was buried at Cimarron. Matthews lamented, "It don't sound very well for a Regular U. S. Soldier to die of starvation in a country where there are plenty, but it is actually the truth." Because the log quarters were dilapidated, the soldiers moved into tents for the remainder of their month's stay at Cimarron. [24]

On Saturday, October 15, 1870, some of the soldiers at the camp attended a New Mexican fandango in the community of Cimarron. There a fight broke out and one of the soldiers was stabbed in the back with a knife, but the wound was not serious. A New Mexican was shot and killed by another trooper named Ford, who claimed the New Mexican threatened him with a knife. This soldier was arrested by the local sheriff. Additional troops, including Private Matthews, were marched quickly from the camp to the town to restore order and return all the soldiers safely to camp. This was done, except for the soldier confined by the sheriff. That soldier was released to his commanding officer the following day but deserted a short time later, assisted by some of his fellow soldiers. Matthews denounced the violence that frequently occurred in civilian communities and declared, "For my part I stay away from those places. There's plenty of fighting to do with Indians without going to these dances to be shot, or cut up with Knifes." A few days later, on November 1, the company returned to Fort Union. The company stationed at Fort Bascom rejoined the Fort Union garrison a couple of days later. [25]

The service at Fort Bascom and Cimarron Agency provided an opportunity for troops from Fort Union to participate in field duty, almost always a welcome relief from the tedium of garrison life. These troops encountered no Indian troubles, but their presence may have prevented Indian resistance. When the troops returned to Fort Union in the fall, they discovered further improvements in progress.

Colonel Gregg, in the interest of sanitation and appearance of the post, ordered that "all hogs found running loose within and around this Post will be taken up by the Guard." The hogs, unlike loose dogs, were not to be destroyed (they, of course, were not rabid either). The owners who claimed the hogs were to be charged a fee, the amount to be set by the post council of administration. [26] Later, when eight hogs captured by the guard remained unclaimed, Gregg ordered them to be sold at public auction a few days later, unless claimed before that time. [27] When it was discovered that cows were also "running loose," they were also directed to be confined. [28]

Another reform came with directions that "smoking (except on the porches in front of the Officers' Quarters) within the limits of the parade ground, and in the corrals and stables, and around the storehouses of this Post, is strictly forbidden." This was not the result of concern about the health of those who used tobacco but part of a fire prevention program. The commanders of troops were to have the smoking regulations "read at different times to the men" at the post. [29]

Additional improvement at the post was achieved with orders that neither officers nor enlisted men were to walk across the parade ground except on one of the established "walks." This may have been a sort of keep-off-the-grass policy, but there may have been little or no grass growing on most of the parade. Decorum was to be further enhanced with the requirement that all officers and enlisted men were, when crossing the parade and "in the vicinity of the guard," required to "have their blouses or coats buttoned." The officer of the day was charged with enforcing these orders. There was one exception. "Enlisted men on extra duty in the Qr. Mr. Dept. whose duties require them to pass and repass the Guard are exempted from compliance with Par. 4," which required that blouses or coats be buttoned. [30]

Colonel Gregg was a stickler for convention. When it was reported to him that some laundresses had used "violent and abusive language," Gregg "announced that if the parties so offending are again reported they will be sent beyond the limits of this Military Reservation and deprived of the ration now allowed them." [31] Gregg also decided that Sunday was to be a day of rest at Fort Union. Following a Sunday morning dress parade and inspection, the officers and enlisted men were to be free from duties so they could "repair to their quarters, reading room or Chapel as their inclination may prompt them." In addition, "all places of business and amusement in the vicinity of this Garrison will be closed on the Sabbath Day." He did concede that "reasonable amusements within the limits of the Garrison are not prohibited." He never defined what he meant by "reasonable." Gregg also directed that a "reading room" be set aside in each company quarters. The room was to be furnished with tables and benches constructed by the soldiers. [32] Later Gregg directed that those who wished to attend church would be excused from regular Sunday morning inspections. [33] The fact that commissioned and non-commissioned officers devoted time to controlling loose pigs and cows, preventing smoking, enforcing sidewalk rules, seeing that blouses were properly buttoned, punishing laundresses who cursed, and keeping the Sabbath was indicative that they were not much occupied with serious military decisions. Other than routine garrison duty and assistance to the supply depots, there was not much demand on the soldiers at Fort Union after 1870.

The need for other posts declined as the Indians were settled onto reservations. Fort Bascom was abandoned in the fall of 1870, and the garrison and all supplies at Bascom were transferred to Union. A small guard was left to protect the vacant post. The guard was considered to be part of the garrison at Fort Union, "absent on detached service." [34] About the same time, the outpost at the Cimarron Agency was closed and those troops returned to Fort Union. [35] Before the troops left Cimarron, a detachment of 21 men was sent under command of Second Lieutenant Edmund M. Cobb, Third Cavalry, from that outpost to assist civil authorities at Elizabethtown in "quelling a disturbance among the citizens of that place." [36]

In December 1870 a special guard detail was organized at Fort Union, comprised of 20 men (five from each company of Eighth Cavalry at the post) including Private Eddie Matthews, to be held in readiness for service when needed. Each man was issued 50 rounds of carbine ammunition and 18 rounds of pistol ammunition. The assignment for this detail was not revealed, and Matthews noted that "considerable curriossity is manifested by every body to know where we are going." Among the speculations were special assignment in Santa Fe, a search for horse thieves, and escort duty for Brigadier General John Pope, department commander. Everyone was surprised when, on December 23, the detail was assigned to guard a shipment of six million dollars being transported to the U. S. Bank at Santa Fe. [37]

Matthews enjoyed the assignment and wrote to his family about it. "Talk of your Rich men," he declared, "none of them ever slept on a more costly bed than I have. I spread my blankets down on the boxes of money and slept as sound as would were I in my bed at home." Because they were on the road on Christmas day, the men of the detail missed out on turkey dinner served at the post. Matthews reported that the detachment "dined on sow bacon and hard tack." Matthews was not impressed with Santa Fe, a "dull and miserable place," where his party arrived the day after Christmas. They were back at Fort Union on January 4, 1871. Matthews was pleased to rejoin the garrison and return to his quarters. [38]

The quarters at Fort Union were filled beyond capacity when the troops arrived from Fort Bascom in the autumn of 1870. Some of the troops from Fort Bascom were quartered "in the Forage Room, Blacksmith Shop, Coal Room and small rooms used for saddlers Shops by the cavalry companies." Some of these rooms had only dirt floors and "the roofs leak badly." Some windows were broken out of the blacksmith shop. Plans were immediately made to repair the windows and roofs and install wooden flooring where required. There was also need for more laundresses' quarters than were available. A total of 20 rooms were made available to the laundresses of four companies and the regimental band, and troop commanders were responsible for the specific assignments. [39]

By 1870 the buildings at the third fort, although some were only four years old, were in constant need of repairs. Colonel Gregg was concerned about the plaster ceilings which kept cracking and falling down. He directed Lieutenant George F. Foote, post quartermaster, to prepare an estimate for lumber to install board ceilings in all the quarters and offices at the post. Foote calculated the cost to be approximately $2,350 for materials. The expense was denied and the improvements were not made. [40] Until the leaking roofs could be sealed, the ceilings would continue to be exposed to moisture.

The ceilings were not the only problem. In November Colonel Gregg reported to district headquarters that "the walls of the public buildings at this Post, in consequence of not being plastered outside, are liable to fall." The walls of many of the buildings had "a tendency to settle outwards, and the constant action of the mud and rain on the soft and pliable adobe will increase this tendency." Gregg did not know what should be done, but he recommended that "a competent mechanic or architect" examine the buildings recommend what repairs were needed. Gregg reported that the mason who had been making repairs to the buildings believed that many of the buildings at the post might fall down within "a year or two." [41] The plight of the structures was overstated, but it was clear that preventative steps were required soon. Adobe buildings required periodic plastering of the exterior if they were to be protected from erosion.

The chief quartermaster for the district, Major Joseph Adams Potter, traveled to Fort Union from Santa Fe to investigate the conditions of the buildings. He concluded, "after a careful examination," that there was "no evidence of a tendency to fall." He found a few places where the adobes had eroded, causing "a slight bulging out." These he considered to be minor problems and declared "in all other particulars the buildings are perfect." They all were in need of replastering on the exterior and some needed to be replastered on the interior. He recommended that the plastering be done as early as possible the following spring. Colonel Getty approved the recommendation and ordered that enlisted men would do the plastering "as early next spring as the season will permit." [42]

Colonel Gregg replaced Colonel Getty as district commander on February 1, 1871. Gregg served until the arrival of Colonel Gordon Granger, Fifteenth Infantry, who assumed the duties on April 30, 1871. [43] Gregg was relieved as commandant of Fort Union on January 31 by Captain Horace Jewett, Fifteenth Infantry. Jewett and Major David Ramsay Clendenin, Eight Cavalry, rotated irregularly as post commander during much of the following year, and Colonel Gregg returned to head the post for brief periods in 1871 and most of the first quarter of 1872. Throughout that time the garrison was comprised of four companies of Eighth Cavalry and one of Fifteenth Infantry. [44]

There was some thought of reoccupying the outpost at the Cimarron Agency in the spring of 1871, but Colonel Gregg decided against it. The primary need for troops at the agency was to oversee the distribution of provisions on issue day. He decided it would be less expensive to send a detachment of one officer and 15 enlisted men from Fort Union "to arrive at the agency on the evening previous to the issue day and . . . return on the day following." [45] Gregg believed that certain interests wanted the troops at Cimarron so they could profit from the soldiers. He was not going to accommodate them. He noted that troops from Fort Union could be on the scene in 12 hours, if needed, and that most of the troubles at the agency resulted from illegal sales of whiskey. He urged that the whiskey traders be controlled by civil authorities. [46] There was even more concern about controlling the New Mexican Comancheros who traded with the plains Indians.

The abandonment of Fort Bascom encouraged many New Mexicans to attempt to reopen the old trading relationships with the Comanches. By late winter 1871, the small guard left to protect the buildings at Fort Bascom reported that "considerable numbers" of New Mexicans were going to Indian Territory. [47] In response, two companies of Eighth Cavalry (D and F) from Fort Union, under command of Captain James F. Randlett (later under Major Clendenin), were assigned to patrol the area between Fort Union and old Fort Bascom and between that point and old Fort Sumner during the spring and summer of 1871. They used old Fort Bascom as their base of supply (supplies sent there by wagon trains from Fort Union) and operations. Their primary mission was to stop any New Mexicans "engaged in illegal trade with the Indians" and to confiscate the property of such traders. They were also to watch for and attempt to prevent any Indians coming from the east into New Mexico Territory. Farther east, two companies from Camp Supply, Indian Territory, were assigned to similar duty in the region between Camp Supply and Round Mound near the Santa Fe Trail in northeastern New Mexico Territory. [48] These patrols saw few plains Indians but were able to catch more than 30 Comancheros. Their presence probably deterred others from going to Indian Territory. It was a good year for the troops from Fort Union. It was the beginning of the end of the Comanchero trade.

Randlett reported early in May that "no trails of Indians have yet been found and no reports of depredations commited by them have been reported by citizens." [49] That situation remained true through the summer season. A few days later, on May 9, Lieutenant Andrew P. Caraher, Eighth Cavalry, and 28 men captured 22 Comancheros (mostly Pueblo Indians from Isleta) and confiscated approximately 700 head of cattle, 10 ponies, and a pack train of 57 burros loaded with trade goods. Many of the cattle were lost because the small detachment had its hands full looking after the prisoners and other property, but they held onto some 300 head until they reached Fort Bascom. The prisoners and their property were taken to Fort Union, during which time another 100 head of cattle were lost, and then to Santa Fe where they were turned over to the superintendent of Indian affairs. [50] On June 12, 1871, Superintendent of Indian Affairs Nathaniel Pope at Santa Fe received 21 prisoners, 198 head of cattle, 46 burros, and 11 horses. The brands on the livestock were recorded so they could be returned to their owners if possible. [51]

On May 28 Captain Randlett and his detachment, guided by Frank DeLisle, captured 11 Comancheros, a Comanche woman who was guiding them, and a pack train of 23 burros carrying ammunition, cloth, bread, trinkets, whiskey, and other trade items. The trade items were destroyed and the burros were killed. The Comancheros claimed to be residents of Santa Fe, San Miguel, and Mora. The following day Randlett's party captured a herd of some 500 cattle, which may have been stolen in Texas by the Comanches to trade to the New Mexicans. Only one of the New Mexican herders with the cattle was captured, the rest escaped. There were also 26 burros with the cattle herd which were captured; 14 of these burros were killed. The cattle, remaining burros, and prisoners were taken to Fort Bascom, then the prisoners and some of the cattle were sent to Fort Union. The prisoners were held until civil authorities could prosecute them for violation of laws prohibiting trade with the plains Indians. The livestock and other property were held by the army, to be claimed by the legal owners if such ownership could be substantiated. [52]

The commissary officer at Fort Union was authorized to slaughter any of the captured cattle that were "fit for issue to the troops." He was to keep a record of brands and weights so legal claimants could be compensated. [53] The captured cattle that were kept at Fort Bascom were also slaughtered and issued to troops under the same orders. [54] In November 1871 some 400 captured cattle, which had not been claimed or slaughtered, were sold at public auction at Fort Union. [55]

The prisoners were turned over to civil authorities at Santa Fe in July so a grand jury could consider the charges against them. They were indicted for "carrying whiskey into Indian Country." The cases were all dismissed because of the ineptitude of U.S. District Attorney S. M. Ashenfelter. [56] The remaining property held at Fort Union and Fort Bascom was turned over to the U.S. Marshal for the territory, John Pratt. [57]

The capture and punishment of Comancheros were applauded by a Santa Fe newspaper:

We trust that the good work may go on until this nefarious trade is most thoroughly broken up. It has long been a disgrace to our Territory, and the cause of untold loss and suffering to the frontier settlers of Texas. Let the troops be kept in the field, and summary justice be meted out to all traders found in the Indian Country, and in a short time they will find out that the profits attending such unlawful expeditions will not compensate for the risk incurred. [58]

A week later the same newspaper reported more favorable results:

The vigorous campaign opened by the military authorities upon the Comanche Traders is already showing its effect. We learn from Las Vegas that a number of parties who left the settlements to trade with the Comanches have returned without effecting their object, hearing of the recent captures . . . they made all haste back to their homes with a firm resolve to make a living in some other and more lawful manner than trading with Indian thieves, as long as the scouts were kept in the field and their illgotten booty liable to be taken from them every minute, and they themselves made amenable to law. Let the troops be kept moving, and let every trader caught be made to suffer the extremest penalty of the law. [59]

An additional company of Eighth Cavalry was sent from Fort Union to join the two companies operating out of old Fort Bascom in August. [60] The patrols along the eastern portion of the territory were increased because of rumors that many Comancheros had evaded the troops in the field and gone into Indian Territory. There was also fear that the Kiowas and Comanches might attempt to raid some of the eastern settlements in New Mexico. In addition, the troops were to escort a railroad survey party when it arrived in the area in September. With the approach of the winter season, the troops operating out of Fort Bascom were directed to return to Fort Union by November 15. Although they had continued to patrol the region after the capture of Comancheros in May, no more traders were encountered by the troops. They arrived at Fort Union on November 18. A small detachment, one officer and fifteen men, was left to guard Fort Bascom. [61] The Comanchero trade was virtually destroyed the following year by troops and citizens in Texas, the main victims of the Indians who stole their livestock to trade to the New Mexican traders.

During the summer of 1871, while many of the troops from Fort Union were away on field duty, another bathhouse was authorized. The adobes were to be made by prisoners, the lumber and other materials were to be purchased by the quartermaster department, and the depot quartermaster was to be in charge of construction. [62] The size and location of this bathhouse were not determined, and it may not have been built at all. Almost a year later the new post surgeon, Blencowe Eardley Fryer, requested that a suitable building be erected at Fort Union "to be used as a bath house for the enlisted men." Until that bathhouse was completed, he recommended that the men be "marched to the spring creek [Wolf Creek] below the Post at least twice a week & there be made to wash their bodies thoroughly." [63] In 1871 lumber was also purchased to build covers over the cisterns at the post hospital. The protective platforms on the cisterns may have been a safety measure decided upon following the death of a prisoner, Private John Mitchell, who fell into a well in the post quartermaster's corral and died on July 29.[64] Other improvements included the construction of partitions for the stalls in one of the cavalry stables. [65]

For the most part, the troops at Fort Union enjoyed a quiet winter, 1871-1872. On February 2, Captain Hobart and a detachment of Eighth Cavalry were sent to Trinidad, Colorado Territory, at the request of the sheriff, to aid in the enforcement of law and order. The cause of the problem was not explained, but the troops were directed to remain until they were no longer needed. The detachment returned to Fort Union on February 17.[66]

In the spring of 1872 Colonel Gregg and three companies of the Eighth Cavalry were ordered to march from Fort Union to the vicinity of Fort Bascom at "a suitable place on the Canadian River" to perform patrol duties, as were done in 1871, during the warm season. If possible, they were to bring to an end the centuries-old trade between New Mexico and the Comanches. A guide and packer were employed to assist the troops. The troops were supplied from Fort Union. Colonel Gregg planned to take his command into Texas and stop the illicit trade. [67] Eddie Matthews, Company L, Eighth Cavalry, was among the troops encamped near old Fort Bascom during the summer of 1872. There he served as a clerk and, in letters to his family, described the encampment and activities of the troops stationed at that outpost. [68]

During the spring of 1872 there were outbreaks among the Utes in northwestern New Mexico and among Apaches in southwestern New Mexico, but troops from Fort Union were not involved. [69] While Gregg's command was in the field, he received orders to send one of the companies to the area of old Fort Sumner to try to capture "the horse and cattle thieves now supposed to be there." [70] Eddie Matthews was a member of the scouting expedition and kept a detailed journal. He pronounced the campaign a "failure" and concluded: "We accomplished nothing, and the cost of the expedition will greatly add to the 'National Debt'." [71]

In June an officer and 15 men were sent from Fort Union to establish an outpost at Cimarron for two months. They were to watch for horse thieves and outlaws and assist civil officers as requested. Lieutenant Edmund Luff, Eighth Cavalry, was in command. The supplies came from Fort Union. [72] The results of their efforts were not found. A month after they were sent to Cimarron, Luff's detachment was directed to leave that outpost and join Gregg's brigade on the Canadian River. [73] Company M, Sixth Cavalry, under command of Captain William Augustus Rafferty, was transferred to New Mexico and assigned to occupy the outpost at Cimarron to assist civil authorities in catching "desperados." These troops were under the command of the post commander at Fort Union and were supplied from Fort Union depot. In August the troops at Cimarron were sent to help search for cattle thieves south of old Fort Sumner. [74]

In the summer of 1872 a party of approximately 90 Texan citizens, led by rancher John Hittson, headed for New Mexico, determined to recover as many cattle as possible that had been stolen in Texas by Indians, traded to the Comancheros, and disposed of in New Mexico. Colonel Granger encouraged their efforts, provided them a letter of introduction to Colonel Gregg, urged Gregg to loan the Texans weapons if needed (or make arrangements for Captain Shoemaker at the Fort Union Arsenal to loan weapons), and directed that the troops "co-operate with these gentlemen in securing such of their cattle as may be found." [75] For several weeks, Hittson's company traveled in New Mexico and claimed approximately 6,000 head of cattle. They violated the civil and property rights of citizens, with the apparent approval of the army, and took cattle without benefit of legal authority or due process of law. On August 1 District Commander Granger changed his views on the Texans and directed the troops at Fort Bascom "take no part in the matter . . . except to prevent bloodshed if possible." [76]

Many New Mexicans protested the loss of their livestock, and the citizens of Loma Parda near Fort Union resisted the Texans when they attempted to inspect cattle in the area. On September 10, 1872, about 60 Texans attacked the village of Loma Parda, killed two citizens (Edward Seaman, who was chief of police and postmaster at Loma Parda, and Toribio Garcia), wounded several others (including the alcalde), and took any cattle they believed to have come from Texas. The New Mexicans then turned to the courts for relief and stopped the invaders, some of whom were arrested for the murders at Loma Parda. The accused killers escaped from jail and were not brought to justice. [77]

The Hittson raids, focusing on the receivers of cattle acquired by the Comancheros, helped to end the trade. The presence of Gregg's command also contributed. The troops found neither Comancheros nor stolen cattle during 1872, indicating that the trade had either been repressed or the New Mexican traders had been able to avoid detection. Gregg did lead his troops far into Texas, in the area of Palo Duro Canyon, where they were attacked by a party of Kiowas. The troops suffered one man injured, three horses killed, and lost the cattle herd they brought with them for food. The Kiowas reportedly had four killed and eight wounded. Gregg found no evidence of New Mexican traders on the plains during his expedition. [78] The troops at Fort Bascom returned to Fort Union in October, and one non-commissioned officer and three privates were left to guard the vacant post on the Canadian. [79] The Comancheros continued to decline and were of little significance after 1872. The illegal trade ended with the defeat of the Comanches in the Red River War, 1874-1875. The troops from Fort Union were a significant factor in the termination of traditional relations between New Mexicans and the Indians of the southern plains.

Colonel Gregg was to send one company of Eighth Cavalry troops from Fort Union to Fort Bascom early in March 1873 because the Kiowas and Comanches were reportedly raiding ranches in the area. Another company was to be kept "ready to move at a moment's notice." [80] Second Lieutenant Alfred Hibbard Rogers, Eighth Cavalry, was assigned command at Fort Bascom and ordered to keep scouts out in search of Indians. Lieutenant Luff arrived and assumed command a few days later and another company of cavalrymen followed. Captain Samuel Baldwin Marks Young, Eighth Cavalry, took command at Fort Bascom in May. The soldiers, assisted by a guide and civilian packers, were kept in the field to help protect the herds of ranchers in the region. The troops at Bascom were supplied from Fort Union. This required transportation for 250,000 pounds of freight. [81]

There was at least one engagement between troops and Kiowas. A small detachment of Eighth Cavalry and several citizens pursued a party of 17 Kiowas that had raided a ranch near Fort Bascom. They overtook the Indians encamped in a small canyon and attacked, killed five, wounded several more, and captured considerable property. According to Eddie Matthews, this was "the first time for years that any of these marauding parties have been caught and chastized." [82] That engagement and the continued presence of the troops at Fort Bascom, and in the vast area which they examined through a system of constant scouting, apparently caused the Indians to leave the area. It was frustrating work for the soldiers, but the resulting peace was rewarding. The troops from the "summer camp" returned to Fort Union in October. A small guard was left at Fort Bascom. [83]

Major Andrew J. Alexander, Eighth Cavalry, served as commanding officer at Fort Union during the winter of 1873-1874. He was absent from the post between March 23 and April 13, 1874, because of the death of his mother at St. Louis. When Alexander received a telegram on March 23 that his mother was dying and requesting him to come immediately, the eastbound stage had been gone from Fort Union only about 10 minutes. The major set out in an ambulance a short time later and caught the stage about 10 miles from the post. The stage carried him to the railroad in Colorado Territory, and he quickly crossed the plains. It was not determined if he reached his mother before her death. He was back at Fort Union within three weeks. [84]

Major Alexander organized a school of instruction for signaling at Fort Union, selecting three men from each company stationed at the post to learn the skills of communication developed by the Signal Corps. [85] Soldiers from other posts in New Mexico were also sent to Fort Union for signal training. It was not possible to determine from available records how effective signaling was in field operations, but it may have assisted the troops in dealing with Indian adversaries. Indian resistence to the loss of their homelands continued.

In March 1874 there were rumors that the Kiowas were "hostile and would be troublesome." This information came from some Comanches who proclaimed that "they were friendly & were not going to war this summer." [86] Early in May Major Alexander and three companies of the Eighth Cavalry were sent from Fort Union to establish a summer camp at or near old Fort Bascom, as had been done in previous years. They were to watch for any Indians off the reservations and were authorized to attack such Indians and force them back to their assigned reserve. These troops received supplies from Fort Union. [87] In June two of the companies were recalled to Fort Union from Fort Bascom. [88] It was anticipated that Indians might leave their reservations and strike at settlements during the summer of 1874, but it was not known where such attacks might occur. Most of the raids occurred on the plains of Kansas and Texas, but a few extended into New Mexico Territory.

The first report to reach Fort Union in 1874 indicated that Indians had struck settlers along Vermejo Creek several miles east of the village of Cimarron on July 5, killing two men and stealing about 20 horses. It was thought they were Cheyennes, perhaps a party of 60 men. Major Alexander led a detachment from Fort Union to pursue those Indians and capture them if possible. On July 7 it was reported that Indians had killed three "Americans" and run off about 200 horses near the Canadian River. A few days later a civilian traveler arrived at Fort Union and reported that a party of about 60 Cheyennes and Arapahos had escaped down the Cañon of the Dry Cimarron with considerable amount of stock a day or two ahead of Alexander's command." Alexander returned to Fort Union on July 13, having seen no Indians. [89]

Major Alexander had gathered information along the way and reported that there were an estimated 400 Indians, including Cheyennes, Arapahos, Kiowas, and Comanches, who had attacked settlers on the Vermejo, Canadian, and Dry Cimarron about the same time, killing altogether 23 men, capturing one "Mexican woman," and stealing an undetermined amount of livestock. He had pushed his command on their trail toward Rabbit Ear Creek but returned when it became clear that the troops could not overtake the Indians. Colonel Gregg directed Major Alexander to send two companies of the Eighth Cavalry to patrol the region between Fort Union and C. O. Emery's Ranch on the Dry Cimarron River, along the road to Kit Carson, Colorado Territory, that passed through Trinchera Pass (also known as Emery Gap), and to the east of that road toward Rabbit Ear Creek. Alexander sent Second Lieutenant Richard Algernon Williams and 37 men of Company B, Eighth Cavalry, toward Emery's Ranch on July 17. Company M, Eighth Cavalry, was held at Fort Union until some of its members, who had been sent to watch along the Cimarron and Canadian rivers, returned. Alexander was directed to take command of the troops in the field himself and see that "frontier settlements" were protected. [90] These troops contributed to the safety of the region, but raids were reported outside the areas patrolled.

On July 8, at Stone's Ranch southeast of Las Vegas, an estimated 12 Indians drove off the horse herd of the ranch. Captain Louis Thompson Morris, Eighth Cavalry, who was at Fort Bascom, was sent with a detachment of cavalrymen in pursuit of that raiding party. [91] These Indians were not found. To assist the troops, Colonel Gregg authorized the recruitment of 25 to 30 Indian scouts among the Jicarillas and Utes at the Cimarron Agency. The number of scouts, by orders from department headquarters, was reduced to 10. As soon as these Indians were outfitted with arms and ammunition at Fort Union, they were sent, on July 28, to Emery's Ranch to join the troops in that area. [92]

On July 22, the same day Major Alexander left Fort Union to lead his command toward Rabbit Ear Creek, word arrived that some 400 to 500 Comanches had been seen near a ranch on the Dry Cimarron where they were "driving off stock of the settlers." A courier was sent to inform Alexander. [93] A company of Eighth Cavalry stationed at Fort Garland was sent to report to Alexander and to patrol along the road between Emery's Ranch and Granada in Colorado Territory. [94] Alexander and his troops found no evidence of Indians, and Alexander believed the recent reports of Comanches on the Dry Cimarron were false. [95]

In case they were not false, Major William Redwood Price, Eighth Cavalry, commanding at Fort Wingate, New Mexico, was ordered to bring "all available Cavalry at your Post to Fort Union." From Fort Union they could be dispatched quickly to scenes of trouble. [96] Still no Indians were found by the troops in the field. Their presence in northeastern New Mexico Territory may have caused the Indians to seek plunder elsewhere.

The outbreak of Indian warfare developed into what became known as the Red River War, 1874-1875, the final series of conflicts in the wars of the southern plains. The offensive was orchestrated by Generals Sheridan, Pope, and Christopher C. Augur. Similar to the winter expeditions of 1868-1869, the Red River campaign was a multi-pronged attack against tribes in Indian Territory, including columns from Fort Union, New Mexico (commanded by Major Price), Fort Dodge, Kansas (led by Colonel Nelson A. Miles, Fifth Infantry), two units from Texas (commanded by Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie, Fourth Cavalry, and Lieutenant Colonel George P. Buell, Eleventh Infantry), and a column from Fort Sill, Indian Territory (Lieutenant Colonel John W. Davidson, Tenth Cavalry, who had served at Fort Union in the 1850s).[97]

Major Price and the four companies of Eighth Cavalry (a total of 225 officers and men, plus six Indian scouts and two guides) he led from Fort Union on August 20, 1874, to old Fort Bascom and down the Canadian River played only a small role in the Red River War but, as part of the "surround" of the Indians, that part was important. These troops were not involved in any major engagements, yet their presence prevented the Indians from having a route to escape from some of the other, larger columns. Fort Union also contributed to the effort by sending supply trains to the troops in the field. There were not enough army wagons to carry the required commodities, and a private wagon train was contracted to haul the excess freight. [98] Price also drew provisions from Camp Supply, Indian Territory, when in that area. The Fort Union Arsenal contributed arms, ammunition, and a mountain howitzer. [99] Price's column returned to Las Vegas on January 25, 1875, from which point the companies were sent to join post garrisons (one to Fort Union, two to Fort Wingate, and one to Fort Stanton).[100] After the Red River War, there was no further need for soldiers at Fort Union to be called out to face plains warriors. The railroads and overland routes to New Mexico were no longer threatened, the first time since Fort Union was established in 1851.

Because of Colonel Gregg's poor health, he was temporarily replaced as department commander by Lieutenant Colonel Thomas C. Devin, Eighth Cavalry, on October 22, 1874. On October 26 Captain Young returned to Fort Union from his station at Emery's Ranch and assumed command of Fort Union. Lieutenant John Wesley Eckles, Fifteenth Infantry, who had been commanding the post since Major Alexander left on May 5, questioned Young's authority to usurp the position. An appeal to Lieutenant Colonel Devin at Santa Fe elicited an immediate response that Young was officially assigned to duty at Emery's Ranch and could not take command of Fort Union. Young then claimed he had brought the Ute scouts in to be mustered out of the service and would return to Emery's Ranch. Eckles remained as commanding officer until Major Alexander returned on November 22, 1874. [101]

Alexander noted the "wretched condition" of quarters, barracks, and stables at Fort Union, which were deteriorating badly. He appointed a board of officers to examine and report on the situation. The board confirmed the seriousness of the state of the structures and urged "the necessity of immediate action." Alexander emphasized that "a year or more delay in repairing will place most of the quarters past repair." He was convinced that, if repairs were not made soon, the rear wall of the commanding officer's quarters would fall down. Also, "the ceilings in all quarters are continually falling endangering lives and property." He believed it was "a hopeless task to attempt to get any money" for improvements, Alexander felt obligated to "represent the facts" of the problem. [102]

His feeling of hopelessness was borne out when his request for funds was not approved. He renewed a plea for repairs a few months later, pointing out that "there is not a house in the Post that does not leak and I do not think there is one that has not some sickness in it in consequence." [103] A few weeks later, more frustrated that nothing was done, Alexander requested that district headquarters send an inspector to look at the condition of the buildings. He reiterated the urgency of doing something. "If it is the intention to maintain the Post some prompt measures should be taken to repair it. The buildings are washing away. The roofs worthless, fences & gates rotting away, and the whole place out of repair." [104] In less than a decade after most of the buildings of the third post was built, the evaluations of their condition sounded remarkably similar to the analyses of the buildings at the first post during the late 1850s.

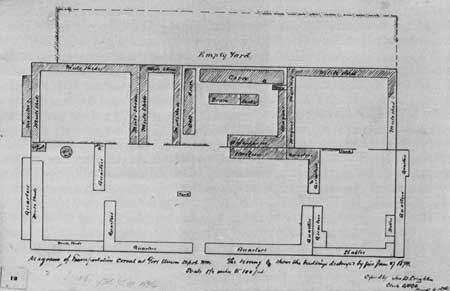

While the post was badly in need of repairs, the quartermaster depot was constructing a "new corral, stables, shops &c." [105] That was necessary because a fire at the depot on June 27, 1874, had destroyed a large portion of the transportation corral along with the corn house, mule sheds, buildings where oats and bran were stored, wagons, ambulances, and teamsters' quarters. No animals had been lost. The loss of forage was extensive, including 604,195 pounds of corn, 57,318 pounds of bran, and 15,244 pounds of oats. Transportation equipment destroyed included five ambulances, three escort wagons, four army wagons, one traveling forge, and "a number of other articles." The fire apparently started in the corn house or a privy beside the corn house about noon and spread quickly, engulfing an area some 600 feet long and 300 feet wide. It took twenty minutes to get the fire engine working, and the fire was finally checked about 2:30 p.m. from spreading into other parts of the depot while the area on fire burned itself out. Captain Gilbert C. Smith, depot quartermaster, planned to rebuild with adobe. [106] The replacement, the "new corral, stables, shops &c.," were what Alexander noted.

|

| Sketch showing (scored area) portion of transportation corral and buildings at Fort Union Depot destroyed by fire on June 27, 1874. Misc. Fortifications File, Cartographic Branch, RG 77, National Archives. |

Soon after his return in the fall of 1874, Major Alexander was assigned to inspect that work and report to district headquarters. [107] Given the condition of the buildings at the post, which received no attention while the quartermaster corral was being built, Alexander must have thought about the criticism of the quartermaster department that had been popular since the Civil War, "the quartermaster department thinks the army exists for its benefit rather than vice versa." He asked Captain Shoemaker, who "has had great experience in this kind of work," to assist with the inspection. Alexander found the work to be "the most economical work I have seen in this country," and stated that the adobe wall of the new corral "will last as long as any adobe wall at this Post." [108]

There were still occasional calls to investigate Indian depredations. Following the theft of some 5,000 sheep along the Pecos River near Anton Chico by unidentified Indians, Captain Young and 35 cavalrymen were dispatched from Fort Union on December 20, 1874, to attempt to capture the Indians and recover the sheep. Young returned to Fort Union on December 29, having lost the trail of the Indians and sheep because of deep snow. [109]

The raiders were believed to be Mescalero Apaches. The troops from Fort Stanton were in the field and more were needed. Captain Young was assigned to command a detachment of 35 cavalrymen, outfitted for field duty and sent from Fort Union to proceed down the Pecos Valley, help search for Mescaleros, and "clean out all Indians you find off reservations." [110] The troops from Fort Union were not involved in any of the engagements with the Mescaleros which resulted in most of them returning to their reservation by early April. [111]

While some soldiers were chasing Indians, others were requested to deal with civil disturbances. Because of the presence of a large lawless element at Cimarron and the inability of local authorities to keep the peace, the attorney general of New Mexico Territory, under directions from Governor Marsh Giddings, requested troops from Fort Union to help Sheriff Isaiah Rinehart restore order at Cimarron. Lieutenant Colonel Devin requested instructions from department headquarters and was informed that troops could be used in civil affairs only by a request from a U.S. Marshall or by orders from the president. [112] No troops were sent at that time, but troubles continued at Cimarron that eventually required military intervention.

There was a brief Indian scare in the spring of 1875 when a group of Cheyennes left the reservation in Indian Territory and headed north. It was feared they might raid in northeastern New Mexico, as they had done the previous year, and 50 mounted troops were sent from Fort Union under command of Captain McCleave to the Dry Cimarron to keep watch. They were to leave a detachment at Emery's Ranch and proceed to Willow Spring Creek some 50 miles farther east. From there, the troops were to scout the area as far north as the Arkansas River. When it was later learned that the Cheyennes had crossed the Arkansas in Kansas on their way northward, the troops were called back to Fort Union. [113] There would be other false alarms.

An incident at the St. James Hotel in Cimarron in early June 1875 resulted in the death of one soldier and the wounding of two others, heightening tensions that were already intense, as will be shown later. The fight occurred during a monte game, in which Francisco "Pancho" Griego was dealing for several soldiers of the Sixth Cavalry. Difficulty arose over the betting, and one of the soldiers grabbed part of the money on the table. Griego quickly gathered the rest of the money, and some soldiers attempted to take it from him. Griego drew a pistol and a Bowie knife and the troopers fled. Griego fired after them, killing Private Shien (first name unknown) and wounding two other privates. The men who were shot had not been involved in the fracas. Some soldiers went to their camp and got their weapons, but Griego escaped. [114] Griego was soon to be a victim in the Colfax County War.

Meanwhile, on June 7, 1875, Colonel Gregg returned from sick leave and resumed command of the District of New Mexico. A few days later Gregg was notified that his regiment, Eighth Cavalry, would soon be sent to Texas and the Ninth Cavalry (a regiment of black soldiers commanded by white officers), then in Texas, would be assigned to New Mexico. The transfer occurred in stages, a few companies at a time, over a period of several months. During the same time, the Fifth Cavalry traveled across New Mexico from Arizona to Kansas and the Sixth Cavalry was sent from Kansas to Arizona. Most of those troops stopped briefly at Fort Union; some of them exchanged horses and transportation at the post. General Pope and his staff visited Fort Union on the way to Santa Fe in July. At the beginning of November Colonel Granger returned to Santa Fe and replaced Colonel Gregg as district commander. The first troops of the Ninth Cavalry arrived at Fort Union on December 20, and Major James Wade of that regiment assumed command of the post. [115]

The next demand for troops at Fort Union resulted from developments at the Maxwell Land Grant, the breakdown of law and order in the community of Cimarron, and the precarious situation of Moache Utes and Jicarilla Apaches who resided on the grant. An overview of the complex circumstances is necessary to understand the participation of the soldiers in events that should have been resolved by civil authorities and the department of Indian affairs. [116] The Jicarilla Apaches and Moache Utes had been permitted to remain on the Maxwell Land Grant and had not been assigned a reservation. They considered the area their homeland and drew rations at the Cimarron Agency. They supplemented those provisions by hunting, but game became scarce in the area as the numbers of ranchers, farmers, and miners increased on the grant.

The Indians' situation on the Maxwell land was changed for the worse with the discovery of gold on the grant at Elizabethtown in the late 1860s and the sale of the grant by Maxwell to the Maxwell Land Grant and Railway Company (a corporation backed by British and Dutch capital) in 1870. The new owners wanted the Indians moved off their property and they wanted all settlers, except those who purchased land from the company, to remove themselves or be forced off the grant. The settlers wanted title to the land they had claimed, and they also wanted the Indians moved someplace else. The turmoil created by the struggle between the managers of the company and the people they considered to be squatters added to the frustrations of the Indians, who wanted nothing more than to remain where they were.

Some of the directors of the Maxwell Land Grant and Railway Company were territorial officials, including Governor William A. Pile (until he left New Mexico in 1871), T. Rush Spencer (surveyor general for the territory), and Stephen B. Elkins (territorial delegate to Congress and the company's attorney). Also connected with the company were John S. Watts (former territorial chief justice) and U.S. District Attorney Thomas B. Catron. These and others came to be known in New Mexico as the Santa Fe Ring, and their power was influential in much of the territory. Governor Samuel B. Axtell (1875-1878) was accused of collaborating with the Ring. The vigorous attempts of some of those officials (who, with their supporters, were known as the Grant party) to eject ranchers, farmers, and miners, as well as Indians, from the Maxwell Grant created a vocal opposition (known as the Anti-Grant party), including two former employees of the company (William R. Morley and Frank W. Springer) who published a newspaper in Cimarron and a circuit-riding Methodist preacher (Rev. Thomas J. Tolby). Tolby was a correspondent for the New York Sun, a reformist newspaper. He referred to the Santa Fe Ring, in an article published in the Sun on July 5, 1875, as "a many-headed monster." Tolby even went so far as to claim that the Maxwell land really belonged to the Utes and Jicarillas. Tolby was warned by New Mexico Chief Justice Joseph G. Palen (considered to be a part of the Santa Fe Ring) to stop writing such objectionable articles. Tolby declared he would continue. The civil authorities in Colfax County, including Sheriff Rinehart, were considered Grant men, and a number of well-armed Anti-Grant supporters converged on Cimarron. The scene was set for violence.

On September 14, 1875, Rev. Tolby was found murdered on the road between Cimarron and Elizabethtown. His Anti-Grant friends assumed the Grant party (the Ring) was responsible although the case was never solved. It was rumored that he was killed by a hired gunman. Governor Axtell offered a $500 reward for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the murderer. Rev. Oscar P. McMains, a Cimarron preacher and friend of Tolby, led efforts to find Tolby's killer and provided leadership for the Anti-Grant forces. He suspected that a Cimarron constable, Cruz Vega, was involved in Tolby's murder. Some of McMains's partisans captured Vega, tortured him, and hanged him from a telegraph pole outside of Cimarron on October 30, 1875. [117]

Pancho Griego, involved in the fight with soldiers at Cimarron in early June and a friend of the slain Vega, declared he would avenge Vega's murder. Griego was in the St. James Hotel bar in Cimarron on November 1, making threats against several people. Griego believed that R. C. (Clay) Allison, who was present, had been involved. Griego provoked a fight with Allison, who shot and killed Griego. [118] Allison was not charged with any crime since he was defending himself. Before Vega had been killed he implicated Manuel Cardenas of Taos, Dr. Longwill (former contract surgeon for the army and Indian agent at Cimarron, was the probate judge at Cimarron and considered by some to be the leader of the Santa Fe Ring in Colfax County), W. M. Mills of Cimarron (member of the territorial legislature), and Florence Donahue (mail contractor for the route between Cimarron and Elizabethtown, described as "an old and respected citizen") in the murder of Tolby. [119] Later, Rev. McMains was tried for the murder of Vega, found guilty of fifth-degree murder by a jury, and fined $300. His conviction was set aside on a technicality. Another trial was scheduled for McMains but the judge dismissed the charges for inadequate evidence.

Following the murder of Vega, troops were called from Fort Union to investigate and help restore order in Cimarron. Second Lieutenant George Anthony Cornish, Fifteenth Infantry, was sent from Fort Union with 20 men. Upon arrival at Cimarron, he reported that feelings were "very bitter" and "a large number of Texans" were there, "all armed." He placed his detachment under the direction of the U.S. Marshal, who wanted to arrest the four men whom Vega had named as participants in the murder of Rev. Tolby before the mob could get them, find those responsible for Vega's death, and stop the conflict before more people were destroyed. [120] He was partly successful.

Longwill escaped to Fort Union and Santa Fe, after informing Cornish that he was afraid to go to Cimarron where "they would hang him." Whether he had any connection to the death of Tolby was not determined. Mills and Donahue either surrendered to authorities or were arrested. Their preliminary hearing before the justice of the peace at Cimarron on November 10 resulted in the clearing and release of Mills and the holding of Donahue until he could raise $20,000 bail. Cardenas, an escaped convict who had been found guilty of murder at Taos in 1864, was arrested and confessed to the murder of Tolby. He was killed by an armed mob of some 15 to 20 gunmen on the evening of November 10 while being taken to the jail in Cimarron. Lieutenant Cornish reported that he had his soldiers at the scene within five minutes "but everybody had disappeared." [121]

After Cardenas was killed, the situation at Cimarron quieted down. Cornish reported that "the Texans have almost all left town apparently satisfied." It appeared that the civil officials were again in control. "I think," Cornish telegraphed to district headquarters, "there is very little use of my staying any longer." Cornish was ordered to leave Cimarron on November 13. [122] The Maxwell Land Grant feud was far from over, but the soldiers returned to Fort Union. Troops were soon called back to Cimarron because the Jicarillas at the Cimarron Agency became belligerent.

The Utes and Jicarillas at the Cimarron Agency had resisted all efforts to place them on a reservation in some other location. As noted above, troops had to be sent to Cimarron in the winter of 1869-1870 when these Indians became "hostile" because the superintendent of Indian affairs had withheld their annuities and tried to force them to go to a reservation in Colorado Territory. Peace was bought by permitting them to remain. During the winter of 1871-1872 New Mexico Superintendent of Indian Affairs Nathaniel Pope tried to persuade the Moache Utes to move to a reservation in northwestern New Mexico where other bands of Utes were settled and the Jicarillas to move to the Mescalero Apache reservation in southeastern New Mexico. The Indians refused to go.

Superintendent Pope understood that almost everyone on or near the Maxwell Grant, except the Indians, wanted the Utes and Jicarillas removed because their "presence was and is a constant source of trouble, and a cause for a general feeling of insecurity among the people of the neighborhood." Because of the growing tensions in the area, Pope was convinced that Cimarron is not a suitable place for these Indians, and that they are surrounded by influences that render their proper control almost an impossibility." They had become "overbearing" and "unruly." Pope hired Dr. R. H. Longwill, former contract surgeon for the troops stationed at the Cimarron outpost in the late 1860s, to serve as a temporary agent for the Jicarillas and Utes, "for the purpose of feeding and otherwise caring for them until they can be moved." [123]

The Indians were poor and the government rations were insufficient. The Jicarillas and Utes had always hunted game for a part of their food supply, but the increasing settlements in the region and the slaughter of the buffalo on the plains made it more and more difficult for them to supplement their government rations with game. A combination of hunger and pressure to abandon their traditional lands resulted in frustrated resistance in the autumn of 1875. Some of the Indians went to hunt buffalo, but there were no buffalo. On November 16, 1875, when Indian Agent Alexander G. Irvine was distributing beef rations, some of the Jicarillas claimed the meat was spoiled and threw it at the agent. It was not clear how the protest was elevated to violence, but pistol shots were exchanged. Agent Irvine was wounded in the hand and at least two Indians were wounded. The Jicarillas threatened to make war and burn the town of Cimarron. Irvine immediately requested troops from Fort Union. [124]

Lieutenant John Lafferty, Eighth Cavalry, was sent with a detachment and arrived at Cimarron on November 18. Because the Eighth Cavalry was preparing to leave the district and the Ninth Cavalry from Texas had not arrived yet, there were not many cavalrymen available for service at Cimarron. Lafferty had only 15 enlisted men in his outfit. He reported that Agent Irvine wanted the troops to arrest three of the Indians that had been involved in the shooting and to disarm one band that had "become insubordinate." The following day Lafferty demanded the surrender of the three Indians, but he speculated there was "a fair prospect that they will resist the demand." He hoped his troops could "check any hostile demonstration" and declared "things are red hot here." The Jicarillas came into the town of Cimarron, carrying their arms, and presented "a defiant and a determined manner." Agent Irvine understood they had sent for some of the Utes to come to Cimarron from their camps. Somehow one of the three Indians wanted had been taken into custody. The leaders told Irvine that, if the soldiers wanted the other two men requested, they could "go and take them." Irvine requested more troops. [125]

Irvine also informed district headquarters that the Jicarillas had taken their women and children into the safety of mountains, indicating to him that they were prepared to fight. He estimated that the Jicarillas had approximately 250 "warriors" at Cimarron and that the Utes could increase that to 450. [126] Colonel Granger ordered Captain McCleave to take all available cavalrymen from Fort Union to Cimarron to try and preserve the peace. McCleave was instructed: "Actual hostilities will be avoided if possible." McCleave and the 14 remaining men of the Eighth Cavalry, plus Second Lieutenant Cornish and 16 men of the Fifteenth Infantry and a hospital steward, Peter Cornell, reached Cimarron on November 21. [126] William R. Morley (a former employee of the Maxwell Land Grant and Railway Company, the army forage agent at Cimarron, and partner in the publication of a newspaper at Cimarron) raised a party of volunteers among the citizens at Las Vegas and requested 10 guns and 1,000 rounds of ammunition from Fort Union. The request was approved by Colonel Granger. General Pope, when he learned of this, directed that no more arms were to be provided to citizens. The citizens could, however, purchase arms from the Fort Union Arsenal. He declared, "if they will quit selling whisky to Indians it is not believed they will need arms". [128]

The Jicarillas moved away from Cimarron into the mountains when McCleave arrived. McCleave knew the Indians would have to do something to obtain food since they were not receiving their government rations. General Pope started two companies of cavalry from Fort Lyon to Trinidad to be available if needed at Cimarron, and he directed Colonel Granger to get himself to Cimarron and "settle this Indian trouble." The new chief medical director of the district, Surgeon McParlin who had been the first post surgeon at Fort Union in 1851, reported that Granger had suffered a stroke on November 19 and was incapacitated by paralysis of his left arm and leg. Granger was not able to go to Cimarron. [129]

Pope did not believe "that violence" was "at all necessary" but recommended that a Gatling Gun be sent from the Fort Union Arsenal to Captain McCleave at Cimarron, in case it should be needed. This apparently was done. More provisions were also sent from Fort Union for the troops at Cimarron. Because Granger was not available, General Pope sent Colonel Miles, who had performed so well during the Red River War, to Cimarron to take command of all troops and resolve the troubles with the Indians. [130] Miles arrived at Cimarron on December 11, 1875, and saw the deplorable condition of the Indians. They were in no condition to fight and needed food. He immediately ordered an issue of rations to them, including the best beef that was available. He informed the Indians they would not be harmed if they settled into their camps near Cimarron for the winter, where they would be fed. He also promised they would not be moved to a reservation before the following spring or summer. Actually, they were not removed for more than two years. By then the Indians realized the hopelessness of their situation and complied. [131] Captain McCleave and his cavalrymen arrived back at Fort Union on December 20. One of his men, Hospital Steward Cornell, had deserted while the troops were at Cimarron.

|

Lieutenant Cornish was left at Cimarron with a detachment of Fifteenth Infantry to keep watch over the Indians and supervise the distribution of rations. Cornish was also designated as the temporary Indian agent for the Jicarillas and Utes at Cimarron Agency. The commanding officer at Fort Union was in structed to watch the situation at Cimarron, make periodic inspections there, "see that peace is preserved with the Indians," and do whatever "the best interest of the Government and of the Indians may require." The Fort Union commander was also directed to begin estimates of the cost and preparations for the removal of those Indians the following year. [132] Meanwhile Lieutenant Cornish and his detachment settled into the building rented by the Indian department at Cimarron to keep their watch over the Indians. On December 30, 1875, the Ninth Cavalry began arriving at Fort Union. [133]

Colonel Granger suffered another stroke and died on January 10, 1876, at Santa Fe. His body was taken to Fort Union, where it was embalmed by Post Surgeon William H. Gardner, and then shipped to his wife at Lexington, Kentucky. Major James Franklin Wade, Ninth Cavalry, commanding at Fort Union, was transferred to Santa Fe to serve as district commander until Colonel Edward Hatch, Ninth Cavalry, arrived to take permanent command of the troops in New Mexico on February 8. Hatch spent the night of February 4 at Fort Union. Captain Francis Moore, Ninth Cavalry, served as the commander of Fort Union until Major Wade returned on February 10. The garrison at Fort Union was small, comprised of one company of Ninth Cavalry and one of Fifteenth Infantry. [134]

Lieutenant Cornish was having problems at Cimarron, not with the Indians but with those who were to provide provisions for them. The contractor of provisions for the Indians had not sent a representative to Cimarron to issue supplies. Cornish notified Major Wade that, if a contractor's agent did not arrive by January 19, 1876, supplies would have to be purchased in the open market to feed the Indians. In addition, the clerk that had been left in charge of the former agent's store was "on the verge of Delirium Tremens." The clerk was leaving for Trinidad, and Cornish had no choice but to close the store and place it under military guard until someone was authorized to take charge of it. [135]

Cornish was undoubtedly gratified when the new Indian agent, J. E. Pyle, arrived at Cimarron on January 21 and relieved Cornish of his extra assignment. Wade directed Cornish to "remove all the troops from there except such as may be absolutely necessary for his [Pyle's] protection." [136] Lieutenant Cornish concluded that seven soldiers, including a non-commissioned officer, were sufficient at the agency and returned to Fort Union with the rest of his detachment on January 25. While those troops were on the road, Governor Axtell requested Major Wade to leave troops at Cimarron to assist Sheriff Rinehart of Colfax County "to protect the lives and property of citizens in that county, and aid and assist the civil authorities in preserving order and enforcing the laws." The governor's request was prompted by the destruction of the newspaper office and press of the Cimarron News and Press (an anti-Grant and anti-vigilante paper published by Morley, Frank Springer, and Will Dawson). [137] Major Wade responded that he could not authorize the use of troops in civil affairs without authorization of higher authorities. [138]