|

Fort Union

Historic Resource Study |

|

CHAPTER EIGHT:

LIFE AT THE THIRD FORT UNION

Life at the third Fort Union from the days of the Civil War until the post was closed in 1891, as at other western posts, was characterized by a rigid stratification of personnel and strict schedule of routine activities, including roll calls, guard mount, company drill, target practice, guard duty, fatigue details (including the daily supply of water and wood, seasonal work in the gardens, and cutting ice during winter months), kitchen police, maintenance work, sanitation chores, teamster duties, cleanup assignments, dress parades, and inspections. [1] Fatigue details continued to provide a labor force for the army, leading to much criticism by enlisted men who felt such work had little to do with soldiering and that they were exploited as laborers without adequate compensation. [2]

The common labor expected from soldiers may have been a critical factor in the high rate of desertions. Private Charles J. Scullin, who spent considerable time in the guardhouse at Fort Union, including punishment for at least three attempts at desertion, wrote to a Las Vegas newspaper in 1885 and reported that nine out of ten who deserted did so because they had enlisted to be soldiers instead of "flunky laborers." After interviewing other deserters who had been captured, Scullin reported that they had joined the army to carry a gun rather than a pick and shovel. [3] Some observers noted, however, that the soldiers seldom worked hard, managed to kill much time without accomplishing much, [4] liked to complain, and were compensated with extra-duty pay under certain conditions. [5] Abuses of extra-duty pay came by working them less than ten consecutive days. Civilian employees were often present to provide part of the labor required.

Fatigue details were assigned to construct buildings and corrals, build and maintain telegraph lines, construct and repair roads, renovate facilities, and almost everything else that needed to be done. Captain George F. Price, Fifth Cavalry, reported in 1884 while serving in New Mexico that many soldiers deserted because they were too "often in logging camps, making adobes, constructing quarters, building telegraph lines, opening wagon roads, etc." instead of performing "their [military] duties." [6] As a leading scholar of the frontier army stated, "drudge labor occupied most of the time and energy of the troops." [7] Some enlisted men were utilized as servants (known as "strikers") by officers, receiving extra pay of five to ten dollars per month for their services. [8] One soldier, William Edward Matthews, Eighth Cavalry, refused an offer to serve as an officer's servant. As Matthews explained to his parents, "I thanked him very kindly and said I did not enlist for a waiter, I enlisted for a Soldier." Matthews's view of the military caste system was expressed in his observation about officers, that "we are too much of a slave for them now, without going [to work] in their houses." [9]

Soldiers also complained about the omnipresent guard duty, which required them to be on watch for a period of 24 hours every few days (the frequency depending on the number of men available for duty at the time). Private Matthews, Company L, Eighth Cavalry, explained how onerous guard duty could become after his arrival at Fort Union in 1870, when only 12 men of his company were available for duty. Six of those troopers were required to stand guard every other day, and the other six were assigned that duty on the alternate days. Matthews declared, "This thing of only one night in bed would Kill the oldest man living." [10]

Matthews explained to his family the duties of a private soldier in his company under those circumstances at Fort Union, a lengthy description worth quoting in his own words:

Here you get one night in bed. For instance tonight you are on Guard, tomorrow morning at 8 o'clock you get relieved. At nine one hour after coming off Guard you have to Saddle up and go on Herd. Come in with the Herd at 4 P.M. spend one hour grooming your horse, then get your supper. At sundown the Bugle calls you to "Retreat" to answer your name, and hear who are detailed for Guard on the morrow. As there is only 12 men in the company for duty and six on Guard each day, you are not surprised to hear your name called to be ready for Guard at 8 O'clock tomorrow, from Retreat till Tattoo "2 hours", you have to shine your belts, clean your gun, and brasses so they shine like a dollar gold piece in the dark. Next morning at break of day you fall in ranks for Reveille, answer your name, and then march to the stables, spend half hour on the . . . horses, come back, swallow your Breakfast, and then put on all your good cloths, comb your hair, pull on white gloves that after one wearing will stretch large enough to pull on your feet instead. Put on all your Belts, Shoulder your carbine, and then you are ready for Guard Mount with all a Cavalry Man's traps on he would make any pack mule, or donkey, blush to see a poor man carrying more than they could. At the first sound of the bugle, you rush in ranks to be inspected first by your first Sergt. In case he should find a speck of dust on your belts, or in your gun, you are hurryed back in quarters and through the aid of numerous brushes assisted by a Spy Glass you are able to see and remove the troublesome speck. You then rush back in ranks, all in a perspiration and then are marched over to the Sergt Major. He stands as a marker, for you to dress by. Soon as all the details arrive on the ground and form a line, he sings out, right dress, you all cast your eyes to the right. If you can see the second button on the second mans jacket, on your right, you are hunky dorey. But if by accident you should get one foot over the alinement, your liable to have it cut off by the Sergt Major's Saber falling on it with considerable force. The S. M. then brings his saber up in front of his face, which is called a present, and sings out to the Adjutant, who stands some thirty paces in front. The detail is correct Sir. The A. then draws his sword and says very well Sergt. take your Post, the Sergt finds a Post on the left of the detail and hangs up there till his honor the A. inspects your Gun, Belts, then opens your shirt collar to see if that bit of apparel has been to the Laundresses in the course of a couple of months. When he is satisfyed that you are not, to use a soldiers expression "Crummy Lousy", he goes to the next man, and so on till the guard is inspected, the cleanest man is chosen Orderly for the commanding officer. The A. then marches to his Post and brings the guard to a present arms, then he salutes the officer of the day, that worthy, says at the same time raising his hat, March the Guard in review to their Post, the Band strikes up those patriotic tunes. . . . You are then marched to the guard house. During the day you escort prisoners around camp, emptying swill Barrels &c. At night you are put on guard over a stable, lot of wagons &c, with these orders, take charge of this post, and all Government property in view. . . . That is soldiering in a nut shell.

I have spent some time and perhaps wasted some paper foolishly, but that is about as fair a description of our duty here as I can give. . . . This thing of standing Guard every other night, is not very pleasant. [11]

|

| Guard mount on Fort Union parade ground, about 1880, showing guard detail and band near the flag staff with some of the officers' quarters in the background. it appears there is a band stand constructed around the base of the flag staff. Photo Collection, Fort Union National Monument. |

It was not unusual for soldiers to feel that their lives were deprived and their work unappreciated. Private Scullin complained that "a soldier's life is a dismal, thankless one to say the least." [12] Many enlisted men and some officers, even officers' wives, characterized existence at the forts as monotonous, dull, boring, and isolated. Private Eddie Matthews, Eighth Cavalry, informed his folks at home in the summer of 1870 the he anticipated being sent into the field on scouting duty in the near future, an assignment he would welcome. "It is so miserable dull here," he wrote, "that a trip for a month would liven us up a little." He also noted that "we never mount our horses except when get a mounted pass, that is very seldom." [13] Matthews was not sent on scouting duty, however, but he did serve periodically as orderly to the post commander. Even though he had not completed the first year of his five-year enlistment, the young private was homesick and ready to quit military life. He wrote the folks back home, "Would like ever so much to be at home, am tired of Soldiering and Soldiers life." He apologized that he could "find nothing of interest to write you . . . but here it is the same old routine, every day." [14] Matthews testified to the boredom and the relative isolation of garrison life. At the end of his enlistment, as he was preparing to leave Fort Union and return to his home in Maryland, Matthews wrote that he was "tired of the Army and everything connected with it." [15]

As Don Rickey noted in his masterful study of enlisted men in the post-Civil War era, Forty Miles a Day on Beans and Hay (1963), "the rank-and-file regular was psychologically as well as physically isolated from most of his fellow Americans." [16] At the third Fort Union, however, this isolation was not as severe as it had been prior to the Civil War. The boredom and monotony, on the other hand, were about the same as earlier, and soldiers welcomed any type of diversion from their routine existence.

At the third fort they had better facilities and quarters than their predecessors had endured, better even than many of their contemporaries at other forts in the Southwest. An inspection officer declared in 1868, "Fort Union is, beyond doubt, out of proportion to all other Posts in the District, in point of the comforts which have been heaped upon it. They are so far the more fortunate who chance to be stationed there." [17] In 1871 Private Matthews, Eighth Cavalry, provided a brief description of the enlisted men's barracks, quoted here because it was the only such description found.

Our Quarters are plastered inside. In each room are seven upright posts, and places around each post for eight Carbines and Sabers, also place to hang belts on. In each room, "two large rooms for each Company" are about thirty single bunks. First thing after coming from stables in the morning, you roll your bed sack up [and] place it at the head of your bed, fold your blankets up nicely and lay them on the bed Sack. All the bunks look the same. Have one large Leviathan Stove in the room, which will heat all parts of it. [18]

Later improvements added to comfort and convenience. In 1875 the wooden single bunks were supplanted by individual iron cots in the barracks. The completion of the railroad in the area in 1879, an event that contributed to the obsolescence of the post by bringing to an end military freighting on the Santa Fe Trail, facilitated the supply and travel of troops. In 1881 oil lamps replaced candles for lighting of quarters, offices, library, and hospital.

In 1873 Matthews was a clerk in the subsistence department and shared a room with a quartermaster sergeant at Fort Union. [19] He again provided an illustrative description of his quarters, a rare glimpse into living conditions at the post. He recounted the furnishings as he entered the door and walked counterclockwise around the room. The items included (1) "a good size and pretty looking glass" hanging on the wall beside the door; (2) a "small table" below the mirror that was covered with a blue blanket and on which were kept combs, hair brushes, clothes brushes, and brushes for cleaning weapons; (3) a window with calico curtains; (4) a washstand in the corner, with soap and water and "a bench for blacking our boots upon"; (5) on the wall between the washstand and fireplace hung a framed picture (two feet by two and a half feet) entitled "Harvest," representing "a farmer bringing in his grain from the fields"; (6) a fireplace with "a cheerful fire burning," with a mantle on which were kept a half dozen smoking pipes and above which hung "a real pretty picture (steel engraving) called 'Horses in a thunderstorm,'" depicting "two beautiful horses terrified by thunder and lightning"; (7) Matthews's bed on which were kept a bed sack filled with straw, a pillow made of wool in a pillow case, his great coat "folded to give the pillow the requisite height," and five army blankets, and under the bed he stored two pairs of boots, a pair of gaiters, a nose bag, one lariat, one set of horse hobbles, a canvas bag to "carry my clothes when scouting," and "a large bottle of genuine 'Bears Oil,' which . . . is elegant for the hair"; (8) at the head of the bed was a box in which he kept his clothes, above which he had displayed on the wall 14 photographs of his family and friends; (9) on the side wall above his bed hung a picture entitled "Evening of Love," which depicted "a young lady in a pensive mood"; (10) another window which looked out onto the parade ground, with calico curtains; (11) beneath the window a box which held his belts and a collection of items he had gathered during his travels; (12) his roommate's bed, "a nice bed, much better than mine," was beyond that window; (13) on the wall above this bed hung a picture entitled "Morning of Love," showing a young girl with a "happy countenance"; (14) near the head of his roommate's bed hung a pictured titled "Open Your Mouth and Shut Your Eyes"; (15) at the head of the sergeant's bed was a box for his clothing, above which was a collection of pictures, including photographs of his family and friends; (16) on the wall where the door was located was a large clothes' rack covered with a curtain, in which were found stable frocks, two caps and a hat, two sabers, two carbines, two bridles, a saddle blanket, a canteen, and, on the floor, a "box for trash"; and (17) in the center of the room was a table "with a collection of papers, books and other trash too numerous to mention," around which were two chairs and a bench. The size of the room was not given, but it must have been cozy. [20]

The men spent much time in their quarters, but they sought other activities too. Except when they were on guard duty, enlisted men had considerable leisure time available in the arrangement of routine duties. At the same time, however, few recreational opportunities were offered at the post except for the library and whatever pastimes the soldiers provided themselves. Some time was spent at the post sutler's store, where a variety of items could be purchased and recreation was sometimes available. When opportunities were presented, the men left the post to visit entertainment enterprises (providing liquor, gambling, and prostitutes, and euphemistically known as "hog ranches") available nearby. The community of Loma Parda, a few miles from Fort Union, was a favorite hangout for soldiers.

The composition of the enlisted ranks was similar to what it had been prior to the Civil War, with many recent immigrants (particularly from Ireland, Germany, and England, and lesser numbers from Canada, Scotland, France, and Switzerland) volunteering for service. [21] The number of Hispanos was reduced markedly from what it had been during the Civil War (when they were found predominantly in volunteer units), but the postwar regular army enlisted more New Mexicans than had been enticed into the prewar ranks. A new element in the regular army, a direct result of the Civil War experience, was the African-American soldier, serving in segregated regiments under white officers. [22] There was evidence of discrimination against Hispanic and black soldiers by Anglo officers and enlisted men. [23] Most enlisted men, regardless of national and ethnic ancestry, were from the bottom of the economic class structure, predominantly unemployed and unskilled laborers. In most companies there were a few skilled laborers and, less often, professional men (including teachers and lawyers). A large number of soldiers in the late 1860s were veterans, having served in regular or volunteer units during the Civil War.

The quality of military personnel was often deplored by officers and even enlisted men. Eddie Matthews had been in the cavalry only two months when he bemoaned the fact that,

I left my dear home and all that is dear to me in the world to associate myself with the scrapings of the world, for I do think that the Army is composed of the scrapings of Penitentiaries, Jails and everything else combined to make an Army suitable for this Government, both Officers and men. The Officers steal from the men and the men steal from each other. Everything is steal, steal, steal. Well I have only 58 months to serve yet. [24]

Throughout the postwar era, there was a large turnover in enlisted personnel. Thus the regiments were comprised of many (from one-fourth to one-half) inexperienced soldiers at any given time. A small number of troops died each year. The term of service expired for approximately 20% of the enlisted men every year, and only about one-fifth of them signed on for another term. The greatest loss was to desertion, with about one-third of the soldiers departing before the completion of their five-year enlistment. During 1871, the year after a pay reduction, nearly one-third of the troops deserted. The following two years were nearly as bad. When all losses were combined, from 25% to 40% of the enlisted men were lost each year. This was a great waste of manpower and money, and it affected, as Utley expressed it, the "morale, discipline, and efficiency" of those who remained. It also made recruitment of new soldiers a vital part of the army's responsibilities. Good recruits were hard to attract to the rigors and low pay of military life. [25]

After the Civil War the army continued to recruit men between the ages of sixteen and thirty-five for a five-year period. Volunteers under age twenty-one were required to have permission of a parent or guardian, but this prerequisite was frequently neglected. Enlistment and reenlistment were possible at recruiting stations, mostly located in larger cities and at military posts. Fort Union periodically had a recruiting officer. New recruits were not permitted by regulations to have a wife or child, although a soldier could marry during his term of service with the consent of his company commander (wives of enlisted men often served as company laundresses). The ability to read and write was not mandatory until after Fort Union was abandoned. A medical examination was required. [26]

Despite the restrictions on married soldiers serving in the army, and official discouragement of enlisted men being married, the records show that a number of soldiers at Fort Union were permitted to marry. The vows were usually taken before the post chaplain, but some couples were married by civil officials in nearby communities. Virtually no information has been found about most of the parties involved in matrimony in the frontier army, but one such couple at Fort Union has been documented from records and photographs. [27] On August 3, 1873, Private Patrick Cloonan, Company B, Eighth Cavalry, married Bridget Molloy at the post. Both had immigrated from Ireland. Like many of his fellow countrymen, Cloonan enlisted in the army until something better was available. Molloy may have been a servant for an officer's family, but it was not determined how she came to New Mexico.

When Cloonan completed his first enlistment in 1873, Colonel J. Irvin Gregg noted on his discharge papers that Cloonan was "an excellent soldier and most reliable man." Private Cloonan reenlisted in April, married Bridget in August, and was promoted to corporal in December 1873. A few months later he was advanced to sergeant. Bridget served as a laundress for Company B, a common practice, holding the only position for women recognized by the army. The Cloonans remained at Fort Union until January 1876, when Company B was transferred to another station. Sergeant Cloonan received his final discharge in April 1878.

|

|

| Bridget Molloy married Patrick Cloonan at Fort Union, August 3, 1873, and she served as a laundress for his company until they were transferred in 1876. Photo Collection, Fort Union National Monument, courtesy William Duggan. | Patrick Cloonan, Company B, Eighth Cavalry, in his corporal dress uniform, late 1873 or early 1874, at Fort Union. He held that rank only two months. Photo Collection, Fort Union National Monument, courtesy William Duggan. |

Many other soldiers were permitted to marry while in the service, and there were a few exceptions to the rule that a married man could not enlist. One such case at Fort Union, in which a recruit had children as well as a wife, was described by Private Matthews, who wrote the following to his family in the summer of 1870:

We have a new Laundress in the Company. Her husband enlisted a few weeks ago. He was raising stock in the country, and was doing very well till last fall when Indians ran away six hundred head of Cattle for him. . . . They have been very kind to me, have taken several meals in the house. While I was sick, made Tea and toast for me, and sent it to me. Am to take some Ice Cream with them soon as finish this. They are both young and have two children. [28]

The unidentified soldier Matthews described had enlisted because of economic hardship. Many young men joined military ranks because other employment was not available. William Edward (Eddie) Matthews left the home of his English-immigrant family at Westminster, Maryland, in 1869 and traveled to Cincinnati, Ohio, with two companions in search of gainful employment. Without success, the two friends returned home, but Matthews informed his family of his decision to join the army:

We have all been unsuccessful in getting anything to do. I have tried most everything but in every instance was unsuccessful, and as a last resort went down to the Recruiting Office for the purpose of enlisting in the regular Cavalry for 3 years, but found out that they were only taking men for 5 years. [29]

Matthews declared he had little desire to serve in the army, and "if I possibly could get anything let it be what it may I would take it, but there is not much chance for anything else here." [30] He later declared that "more men enlist in Cincinnati, than any other in the United States. If you once get strapped in the miserable place you are bound to enlist." [31] He served a large portion of his term of enlistment in Company L, Eighth Cavalry, at Fort Union, where he continually counted and reported to his family, in letters that averaged nearly one per week, the number of years, months, days, and hours remaining until he would be free from the army. He found conditions to be deplorable, causing many of the soldiers to desert. At one point, irritated by the way soldiers were treated, Matthews declared that "every man in the Regular Army would be justifiable in deserting according to my idea." [32] Matthews, however, was determined to honor his commitment for the entire five years, which he did.

Matthews did not enjoy "the common duty of a Soldier" but declared "I will try to make the best of a bad bargain. And do my duty like a man." [33] He had the good fortune to be selected to serve most of his tenure as a clerk, because he was literate and practiced good penmanship, which exempted him from many of the routine duties of most soldiers. His extensive correspondence to his family, copies of which were presented to Fort Union National Monument Archives in 1993, provided the best view of life in the post-Civil War frontier army by an enlisted man that has been found to date. [34]

Matthews periodically informed his family that his enlistment had been a blunder and he was sorry he had done it. In 1873, after serving more than three years of his term, he wrote to his folks as follows:

What a great mistake I made when I left home. And to make bad worse turn around and enlist in the Army for five years. Had only I bound myself down to some good man, who would have been willing to take and learn me some trade, how much better off would I be now. But regrets will do no good in the present case. I will have to sleep in the bed I made for myself, but I tell you it is a hard bed. [35]

Many other soldiers must have had similar feelings and wondered why they had joined the army. Almost everyone who volunteered was accepted. The screening of potential recruits was not stringent, in order to fill the ranks. Physical requirements for service were specified in regulations for medical examination of recruits, but these were laxly enforced:

In passing a recruit the medical officer is to examine him stripped; to see that he has free use of all his limbs; that his chest is ample; that his hearing, vision, and speech are perfect; that he has no tumors, or ulcerated or extensively cicatrized legs; no rupture or chronic cutaneous affection; that he has not received any contusion, or wound of the head, that may impair his faculties; that he is not a drunkard; is not subject to convulsions; and has no infectious disorder, nor any other that may unfit him for military service. [36]

As important as the selection of recruits was their training, which was generally deficient. Until 1881, when four months of basic training was established at recruitment depots, rookies received most of their training after assignment to the unit with which they were to serve. As noted in the previous chapter, recruits for the District of New Mexico were usually brought to Fort Union and distributed to their respective posts from that point. They generally were delivered with only a rudimentary understanding of basic military skills at best. The introduction to the authentic life of a soldier, when he finally reached his assigned company, most likely terminated any delusions about the romance of military life which some enlisted men may have entertained.

Captain Gerald Russell, a native of Ireland who had entered the service in 1851 as an enlisted man, spent several years as a first sergeant before being promoted to a commissioned officer, and who was stationed at a number of posts in New Mexico Territory (including Fort Union) before, during, and after the Civil War, greeted a body of recruits to his company of Third Cavalry at Fort Selden in 1869 as follows:

Young Min! I conghratulate yiz on bein assigned to moi thrupe, becos praviously to dis toime, I vinture to say that moi thrupe had had more villins, loyars, teeves, scoundhrils and, I moight say, dam murdhrers than enny udder thrupe in de United States Ormy. I want yiz to pay sthrict attintion to jooty—and not become dhrunken vagabonds, wandhrin all over the face of Gods Creashun, spindin ivry cint ov yur pay with low bum-mers. Avoide all timptashuns, loikewoise all discipashuns, so that in toime yiz kin become non-commissioned offizurs; yez'll foind yer captin a very laynent man and very much given to laynency, fur oi never duz toi no man up bee der tumbs unless he duz bee late for roll-call. Sarjint, dismiss de detachmint. [37]

Such an introduction, indicative that pitiless discipline would bring retribution for the slightest infractions of rules and regulations, provided little help for the newcomers. It may have inspired them to regulate their behavior but shed little light on what was expected beyond submission. Without special training in basic military decorum and discipline, the new soldiers were expected to discover their status and obligations in the service through observation and emulation of the veterans, attention to routine activities, instruction, and drill. They were, as one scholar noted, "in a system far more rigid and austere than any environment most of them had previously known." They learned much of what they needed to know from the older men in the company [38]

They learned to obey orders and perform assignments or pay the penalties. Teresa Griffin Viele, wife of Lieutenant Egbert L. Viele (First Infantry) who served on the Texas frontier, proclaimed that "prompt obedience is the first lesson a soldier must learn" and quoted a brief rhyme to illustrate the point:

Theirs not to make reply,

Theirs not to reason why,

Theirs but to do and die. [39]

Eddie Matthews quickly discovered after his enlistment in 1869 that "Officers are very strict, but you can get along very well if you only pay attention." He informed his parents, "I am trying to do right in my new duty." Even so, he wrote, "Every little thing you do the Officers curse you for it, and call you all kind of names," Matthews was pleased that "I have not missed one roll call or had a cross word spoken to me yet. I have made up my mind to do what is right." [40] His efforts were successful. During his time at Carlisle Barracks Matthews was twice excused from guard detail "for being the cleanest man." [41]

Although enlisted men did not need to know why they were to conform, they needed to understand what they were to obey. To help in that regard, army rules and regulations were periodically read to all troops, many of whom were illiterate. Commencing in 1884, every man was issued a copy of The Soldier's Handbook, a pocket-sized guide that detailed most things a soldier needed to know. [42] The guide may have been helpful, but it was difficult to discover the elements of soldiering in a book. Most continued to learn the essentials from the members of their company.

A soldier lived in barracks in close association with the men of his company, enjoying little, if any, privacy. The company, usually not filled to legal capacity and comprised of 40 to 50 (sometimes fewer) enlisted men, was the soldier's "family" during his term of service. The small number of soldiers in a company fostered cohesiveness. The men of a company usually developed a loyalty to the unit and counted among its members their closest comrades. Many soldiers were known to their companions by nicknames, often the result of physical appearance or behavioral traits. As Don Rickey observed, "the company tended to be a self-contained social as well as military unit." With the officers and men of his company, each soldier "would live, eat, sleep, march, brawl, and possibly die." [43] As one soldier declared, "the company is everything to a soldier." [44]

Many soldiers complained about their officers, often with justification. While some officers who had served before and after the Civil War complained about the lower quality of enlisted men after the war compared with those before, [45] other officers deplored a similar decline in the character of the officer class. Duane M. Greene, a retired lieutenant, wrote in 1880 that "it is worthy of remark that the chivalrous spirit which had attained its full perfection in the Army before the Great Rebellion of 1861 is nearly extinct." He explained what had happened, in his opinion.

The present organization lacks that ambition—that esprit de corps—which characterized the Army prior to the war. Some of the senior officers still maintain among them a remnant, though feeble and mutilated, of the essence of the "good old time." . . . Degeneracy has been increased by the appointment of men who have not received a military education. Add to these the "graduates" whom a superabundance of black bile has rendered unsusceptible of refinement beyond the limited demands of civility, and the sum comprises so much of the unit that the remainder is a negative power. The homogeneity that should characterize the military establishment has been destroyed by the mingling of incongruous elements. The contact of the truly meritorious professionals with non-professionals has given rise to arrogance, and has almost annihilated the spirit of chivalry. [46]

The result, as Greene saw it, was that many officers exhibited a "haughty assumption of superiority." He continued:

Rank is the shield behind which they stand to heap tyranny upon insult and wrong. They do not regard inferiors has having rights which they should respect, and by the tyrannical exercise of authority, they extort a slavish obedience from those over whom they are placed. They look upon a private soldier as a machine—animate, yet without sense of justice or wrong; exacting of him the offices of a menial—a serf—degrading him even in his own estimation. [47]

While that may have been true of many officers, there were rare expressions of loyalty and respect for some officers who understood and sympathized with the conditions of enlisted men. In what was undoubtedly an uncommon demonstration of affection for a commissioned officer, in 1870 forty men of Company L, Eighth Cavalry, including Private Eddie Matthews, "put in one dollar each, and bought a very handsome Saddle, Bridle, and Saddle Blanket, and presented it to our Second Lieut." This was Second Lieutenant Edmund Monroe Cobb, who graduated from West Point in 1870 and joined his company at Fort Union in September of that year. Matthews declared that Cobb was "the finest Officer I ever saw that came from that place [West Point]." He was pleased to report that Cobb had "received the present and thanked us very highly for it." Matthews did not record his feelings when Cobb was transferred to the Second Artillery the following year. [48] It may be presumed that the change in personnel affected the emotions of the men in the company.

Each company contained a variety of personalities and backgrounds, a cross-section of humanity. Although there were exceptions, many soldiers had a tendency to consume too much alcohol as a form of escape from the realities of army life. Drunkenness was a problem at all military posts, including Fort Union. The failure of the army to provide leisure activities fostered visits by soldiers to gambling dens, saloons, and brothels in nearby communities, such as Loma Parda just off the Fort Union reservation. Soldiers, and sometimes officers, also developed sporting activities. Fort Union soldiers played baseball in the post-Civil War era. Private Matthews, Eighth Cavalry, noted that some of the men in his company organized a baseball team at Fort Union in 1871. He was selected team captain. When they were sent on scouting duty, they took their "bats and balls along with us, and have been amusing ourselves and passing away the time playing ball." [49] One place where officers and men breached the rigid distinction between their respective classes was at the meetings of Masonic and other lodges, where members of both sides met as equals and followed the rituals and rules of the fraternal orders. Such fraternization seldom extended beyond the gatherings of the lodges.

Among enlisted men, as among officers, rank was important and had its privileges. The commissioned officers had little direct contact with enlisted soldiers and relied upon the noncommissioned officers to handle the daily affairs of the men. The company was primarily managed by the first sergeant who, in turn, depended on the duty sergeants and corporals. They kept the soldiers in line, saw that duties were performed, and enforced discipline. According to Rickey, "if a single word were chosen to describe the noncommissioned officers, . . . that word would have to be—tough." [50] Rickey also emphasized that the noncommissioned officers were the "backbone" of the army. [51] Other noncommissioned officers at military posts included an ordnance sergeant, quartermaster sergeant, commissary sergeant, hospital steward, and a sergeant major who assisted the post adjutant and oversaw the daily change of the guard. Most of the noncommissioned soldiers had a long record of military service, often ten years or longer. A few of them had even served previously as commissioned officers.

Information about most noncommissioned officers who served at Fort Union was as elusive as records about other enlisted men. Thomas Keeshan, who served as commissary sergeant at Fort Union, 1884-1889, was an exception, and his story provides an example of those who filled similar positions in the post-Civil War army. [52] Keeshan was born in Queens County, Ireland, in 1846. He enlisted at New York City on June 21, 1865, when he was 19 years old. He was five feet three and one-half inches tall, with red hair and blue eyes. His occupation at the time of enlistment was musician.

|

|

| Thomas Keeshan, about 1885. He lived until 1943. Keeshan Collection, Fort Union National Monument. | Robina Keeshan, about 1875. She died in 1920. Keeshan Collection, Fort Union National Monument. |

|

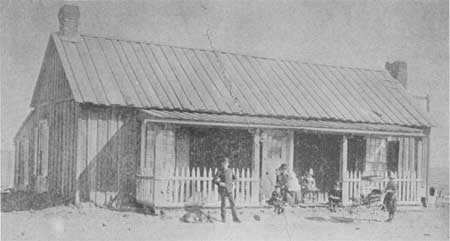

| Thomas and Robina Keeshan with their children (five of their six children survived) at the post commissary sergeant's quarters at Fort Union, about 1887. These board and batten frame quarters were located north of the depot storehouses. Keeshan Collection, Fort Union National Monument. |

|

Keeshan served in several infantry regiments, ending up in Company C, Sixteenth Infantry, with the consolidation of the army in 1869. He was appointed corporal on September 1, 1867, was promoted to company quartermaster sergeant, December 10, 1868, and became first sergeant, October 3, 1873. He married Robina Gibson, born in Scotland in 1859, at Little Rock, Arkansas, on August 6, 1875, when he was 29 and she was 16. They had six children, some of whom were born at Fort Union.

In 1883, while serving at Fort Concho, Texas, Keeshan applied for an appointment as commissary sergeant, and the letters of recommendation submitted to support his application revealed a dedicated, competent, and loyal soldier. His company captain, Thomas E. Rose, wrote on November 23, 1883:

I have known Sergeant Keeshan personally since March 20th 1870. . . . I have found him thoroughly efficient in the performance of every duty that has ever been assigned to him. Intelligent, energetic active & indomitable, he has ever been more than any other soldier I ever saw. In garrison or in the field he has ever been ready for the most important service and was never known to be unequal to any task.

. . . He is a man of thorough business habits, careful active infallible, and his appointment to the position of Commissary Sergeant would make a most valuable acquisition to that branch of the service. [53]

On March 7, 1884, Captain Rose submitted another letter of recommendation, similar to the first but with additional information. Keeshan, he stated, "is a good shot and has been for years back a marksman." More relevant to the duties of a commissary sergeant, Rose continued, "He has for more than ten years done all the clerking of the Company keeping the books records & returns in a good and presentable condition." Keeshan also had improved his knowledge. Rose declared, "From 1870 to 1874 he studied Mathematics under my own tuition during which time he showed remarkable proficiency in Algebra, Geometry, Trigonometry, Surveying, Analytical Geometry, Differential & Integral Calculus & Mechanics." [54]

|

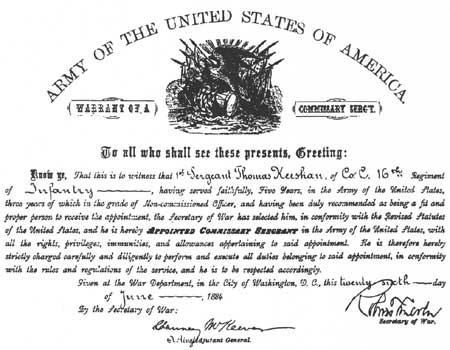

| Thomas Keeshan's appointment as commissary sergeant, June 26, 1884, when Robert Todd Lincoln was secretary of war. Thomas Keeshan File, Fort Union National Monument Collection, New Mexico State Records Center and Archives, Santa Fe. |

Lieutenant William V. Richards, post quartermaster and commissary officer at Fort Concho, stated on November 27, 1883, that he had known Keeshan for 15 years and found him to be "a most excellent 1st Sergeant, a thoroughly reliable, temperate, and responsible man." He noted that Keeshan had "a large and most interesting family, of which he takes most excellent care, and as the time approaches for educating them, the Sergeant naturally wants to improve his condition." Richards concluded by noting that Keeshan was also "an excellent accountant and would make a most excellent Commissary Sergeant." [55]

Keeshan was appointed commissary sergeant on June 26, 1884, and assigned to duty at Fort Union, replacing post commissary sergeant William Bolton. Keeshan and his family lived at the post until he was transferred to Fort Clark, Texas, on October 22, 1889. He later served at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and retired from the service there on September 29, 1894, having served almost 30 years. He settled at Junction City, Kansas, near Fort Riley where he had once served, and operated a greenhouse for many years. He died in 1943, when he was considered to be the oldest army veteran in the United States on the retired list.

|

|

| Lucy Margaret Keeshan, in 1887, youngest daughter of Commissary Sergeant Thomas and Robina Keeshan, was born at Fort Union on May 19, 1886. She died at Manhattan, Kansas, January 1988. Keeshan Collection, Fort Union National Monument. | Walter Keeshan, in 1887, was born at Fort Concho, Texas, October 14, 1883. He lived with his parents at Fort Union, 1884-1889. He died at Junction City, Kansas, September 7, 1984. Keeshan Collection, Fort Union National Monument. |

Lucy Margaret Keeshan, daughter of Thomas and Robina born at Fort Union on May 19, 1886, reported in the late 1960s a story that was part of her family heritage, about how her father kept cash for the commissary department at Fort Union hidden in sacks of beans at his office. Once, when the paymaster came to pay the garrison but the shipment of money had not yet arrived, the paymaster explained his predicament to the post quartermaster and commissary officer. This officer suggested that the paymaster borrow the required funds from Sergeant Keeshan and replace them when the shipment of money came. Keeshan opened some sacks of "beans" and counted out $5,000 to pay the troops. A few days later the payroll funds arrived and the paymaster and Keeshan counted the required $5,000 and concealed it back in the bean bags. Whether folklore or fact, it was a good story. [56]

There may have been some friendship between the commissary officer and Sergeant Keeshan, but most likely they were parts of two different worlds. Just as before and during the Civil War, there remained a vast gulf between the officer class and enlisted men. [57] The Civil War, with its thousands of volunteers and futile carnage, had helped to weaken some of the earlier aristocratic pretensions of many officers and their wives. Countless officers of volunteer units were appointed from civil life and therefore had not been indoctrinated, as some soldiers believed, "by teaching the officer-enlisted man caste system as if it existed by divine right." [58] Nevertheless, as Duane M. Greene, a former officer in the frontier army who wrote a book on military social life in 1880, declared, "the Army is a little domain of its own, independent and isolated by its peculiar customs and discipline; an aristocracy by selection and the halo of tradition." Greene argued that the army was not the paragon "of morality, honor and chivalry that many believe." [59] Although Greene wrote primarily about officers and their wives, he understood the unique station of the ordinary soldier.

|

The enlisted men of the postwar era, whether veterans or newcomers, were somewhat less servile as a class than their prewar counterparts. Even though they were legally subservient to commissioned officers, many enlisted men expected to be treated fairly and with respect. As Rickey asserted, "reciprocal loyalty between officers and men was vital." [60] The rate at which they were subjected to courts-martial for various offenses and the high rate of desertion, however, indicated that military discipline was still harsh (even capricious) and many soldiers failed (by choice or nature) to adjust to the conditions and discipline of the army. [61] At western military posts the conduct of officers strongly influenced the behavior of enlisted men. Drunkenness, for example, was a problem for many men of both classes. Officers and their wives continued to provide more details about military life at Fort Union than did enlisted men, so that much of the information available contains a deliberate or involuntary officer bias. An exception was Eddie Matthews, Company L, Eighth Cavalry, whose prolific correspondence represented the viewpoint of an enlisted man at the post during the early 1870s.

Following the Civil War, a parsimonious Congress reduced the military budget to a point that funds were sometimes insufficient for fundamental activities. The army became a virtual skeleton as the authorized strength of the postwar regiments was reduced from 57,000 (in 1866) to 25,000 officers and men (by 1874). The number of military posts was reduced from a peak of 255 in 1869 to 96 in 1892, the year after Fort Union was abandoned. Sufficient funds were not provided to maintain adequately even the reduced number of military posts and authorized troops. In fact, most companies operated with fewer than the authorized number of enlisted men for many years (in 1881 the cavalry regiments averaged 82% of authorized strength and the infantry averaged 85%, and those figures included the sick, prisoners, and others unfit for duty—many infantry companies did not have 25 men available for duty). [62] The provisions and equipment left over from the Civil War, regardless of condition and serviceability, were utilized by the army for approximately the next decade. At times the availability of ammunition was so limited in the immediate postwar era that the men could not participate in target practice. Marksmanship received much emphasis in the 1880s, a time when there were few military demands on the troops at Fort Union.

The soldiers' pay had increased during the Civil War, part of the inducement to recruit needed volunteers. At the end of the war the base pay for privates was $16 per month, with one dollar deducted and kept until discharge (a forced savings plan to provide a new veteran with a small lump sum to begin life as a civilian and to discourage desertion because soldiers who departed early did not receive it), and a deduction of 12.5 cents for maintenance of the Soldiers' Home in Washington, D.C. Soldiers continued to dispose of their pay in many ways, including payment of debts, sending money to their families, newspaper subscriptions, personal items, additional food, tobacco, alcohol, gambling, prostitutes, and obligations to the company laundress, [63] tailor, cobbler, barber, and others. After the Civil War the army did a better job of fulfilling its promise of paying troops every two months, another practice designed to reduce desertions. Even so, many soldiers borrowed money to make it from one payday to the next, pledging their future pay (a process that took a portion of each payment immediately and necessitated borrowing again, keeping them almost perpetually in debt). In comparison to other jobs (many paying two, three, and four times the amount provided by the army), the soldiers' cash pay looked inferior after the war. When their food, clothing, shelter, and medical care were included, however, the disparity was not as great as it appeared.

Eddie Matthews explained in 1869 that recruits were not paid until they were assigned to a regiment and had served for several weeks. [64] Meantime each new soldier was given $3.00 worth of scrip to be used at the sutler's store "to buy the little necessaries to keep clean and eat." These included "a quart cup, tin plate, knife and fork, and spoon, blacking amp; brush, pr of white gloves, towel and soap, plate powder to clean your plate and buttons, a little thread, for that you pay 2.30." Matthews did not purchase a button brush and used his toothbrush for that purpose. With the 70 cents remaining, he "bought ten sheets of paper and that many envelopes, a little looking glass for ten cents, a comb, some tobacco and mailed one letter." He promised to send his parents "just as much money as I possibly can" after each payday, which he faithfully did during his five-year term. [65]

Matthews sent his family $20 after he was paid in July 1870, stating that it was "not much I know." He explained that, after the deduction for his revolver and payment of the laundress, tailor, and "several others," he had "run pretty short." He commented that he was most ashamed to send so small an amount, but have only kept 5.00 myself to have some pictures taken." [66] Matthews was apparently more concerned than most enlisted men about sending home as much of his pay as possible.

In 1874, near the end of his term of enlistment, Matthews explained in detail how enlisted men spent what money they received. He considered the purchase of supplemental food and the alteration of clothing issued by the army to be primary expenses. Beyond those were many other expenditures:

Then comes your Laundry bill $1.25 each month, and . . . your barber bill is another $1.00 per Mo. . . . One cannot wash his hands and face with Gov't Soap, and this takes a few more dimes. Nearly every soldier wears paper collars in Camp 40 cents a box. . . . Then comes combs, hair and tooth brushes, a little hair oil occasionally (for bacon grease won't answer). . . . The Gov't does not provide you with towels and one cannot always use his shirt tail. Nearly every soldier wears fine boots on stated occasions such as Inspections, Musters, Sundays and many other times. . . . This article of itself in this country costs a months soldiering. . . . These boots will not look well all the time without they are blackened, . . . and then you cannot blacken them without a brush, (a horse brush Gov't issue won't do the work). . . . (1) cloths brush 75 cents then you need several little brushes for cleaning your arms and equipments. . . . Paper, envelopes, stamps, pens, ink and paper are an expense to some. . . . Another little necessary and indespensible article is tobacco, most every soldier uses it. It is one of the greatest comforts we enjoy. . . . Cigars are too expensive and Uncle Sam has failed to supply us with pipes, so you see this is an expense that could not possibly be avoided. . . . There are many other little necessaries to be purchased with our little $13.00 per month, and when it is all added up it leaves a balance of $000,000. [67]

In 1870, in an economy drive in Congress, the base pay was reduced (effective July 1, 1871) to $13 per month with the same deductions noted above. The primary reaction of the troops was a marked increase in desertions. Over 32% of all enlisted men in the army deserted in 1871 and the rate remained high for several years. [68] At Fort Union 84 soldiers deserted in 1871. That was 20% of the average aggregate monthly garrison that year. [69] To help combat desertions, Congress established a schedule of longevity pay increases in 1872. The soldier who completed his required five-year enlistment received an additional one dollar per month for the third year of service, two dollars per month for the fourth year, and three dollars for the fifth year, all of which was retained until the soldier was discharged. The retained funds also collected 4% simple interest. [70] Longevity pay was not sufficient incentive, however, for many soldiers to put up with harsh discipline and other conditions for five years, and desertion remained a serious problem for the army. The tightfisted Congress refused to spend money to reform and improve military life. A retirement plan for enlisted men was not provided until 1885, and it required 30 years of service. [71]

There were idiosyncrasies in the system of pay. Eddie Matthews, who served in the Eighth Cavalry from 1869 to 1874, resigned his noncommissioned office of sergeant in 1873 to become a private and a clerk in the subsistence department. Because he received extra-duty pay for being a clerk, in addition to his private's salary, Matthews was paid $4.20 per month more in that position than he had received as a sergeant. As he explained to his parents, to whom he sent as much of his pay as he could spare, "I am after the dollars and cents, instead of rank." In addition, he noted, "My duties are less bothersome now than they were as Sergt." [72] An anomalous and parsimonious military system affected more than salaries.

Technological improvements in weapons, communication, clothing, accouterments, and other areas were not utilized or were introduced slowly because of the costs involved and the stocks of supplies left over from the Civil War. Army reforms came ponderously slow, too, because changes required revenues and the bureaucracy was inherently reluctant to innovate. Officer promotions were exceedingly retarded because vacancies in the finite positions seldom occurred, and the abundance of brevet ranks continued to cause confusion. [73] Second Lieutenant George B. Duncan, Ninth Infantry, began his duties as a newly commissioned officer at Fort Union in 1886. He described the post commander, Lieutenant Colonel Henry R. Mizner, Tenth Infantry, as "a relic of the Civil War, as were all the captains and many first lieutenants, probably good soldiers in their day but stagnated with inactivity and slow promotion." [74]

The lack of incentives and rewards for outstanding performance of duties was not unique to officers. Because of low pay and low esteem for soldiers, the enlisted men, according to Utley, did not "rise above mediocrity." [75] Some soldiers had little desire to risk their lives for the compensation provided. Perhaps Eddie Matthews, Eighth Cavalry, summed up the sentiment of many of his fellow soldiers when he penned his thoughts during a potential engagement with Indians while on a scouting expedition in 1872:

I knew what had to be done in case we met the Indians. My own life was at stake as well as the Generals or any of the command, and I was willing to risk that life with the rest, but not foolishly. I have too much to live for. Too many bright hopes for the future to recklessly run myself into danger. . . . As regards myself, cant say that I felt very rejoiced at the prospects of a fight with the Indians, $13.00 a month is not an incentive to throw ones life away. And as to my patriotic feelings, I candidly say, I have none. I have never been blessed with the inspiration. [76]

Later, after the Indians his detachment were pursuing had retreated and the officers ordered the troops to withdraw because of a possible ambush, Matthews declared:

And we turned and marched back to Camp. Many were the countenances which brightened up and many were the hearts made glad by this Command. I also experienced a feeling of relief when saw we were marching back to Camp, for have had all the Indian fighting I wish for the remainder of my life. [77]

Throughout the postwar years the capability and efficiency of the nation's military arm stagnated and deteriorated. Fortunately the demands on the army decreased as the Indians of the West were subdued, and places like Fort Union were active but nonessential during the last years of their existence. Significant reform of the nation's army came in 1890 and after, when Fort Union was abandoned. Life at the third Fort Union, without a driving mission, was certainly less exciting than when military action was required, as during the Indian campaigns or Confederate invasion of New Mexico. Even so, the story of people and activities form an important part of the history of the post.

The daily life of the soldier was affected by the quarters in which he lived [78] and the clothing, food, and equipment he was issued. Clothing left from the Civil War, although much of it was of inferior quality, was issued to troops for almost a decade after the war ended. Dress uniforms underwent periodic style changes during the 1870s and 1880s, but the basic dress remained the same: woolen trousers, shirts, blouses, socks, long underwear, forage caps and campaign hats (later helmets), and shoes for the infantry or boots for the cavalry. [79]

In December 1873 Eddie Matthews, Eighth Cavalry, described the changes in clothing just issued to his regiment, the new style being "taken from the Prussian Soldiers." He was pleased with the results.

We have received our New Uniform and are very well pleased with it. It consists of a Helmet with Cords, bands and plume with a large brass Eagle in front, the Cords, bands and plume are yellow. . . . The dress coat is very nice, is trimed with yellow (buff)[,] pants same as before. . . .

We all turned out this morning for Inspection in full rig for the first time and made quite a display. [80]

A few days later he expressed further pride in the attire: "We cut a dashing appearance in our New Uniforms and look quite flashy." [81]

Footwear was poorly constructed and did not fit the shape of many soldier's feet. One soldier recorded that the proper method for breaking in new shoes was to walk in the creek until they were soaked and keep them on until they had molded to the shape of the foot and dried completely. Much of the clothing issued required modifications before it fit the size and shape of the individual. Each company usually had a soldier who performed the duties of tailor in his spare time, altering and repairing uniforms for pay. Many companies also had a cobbler who repaired shoes and boots. [82]

Matthews explained the necessity and expense of utilizing the services of a company tailor:

The great trouble with the clothing is it will not fit you, and for one to dress in Government issue without having it altered is to make yourself a ridiculous looking object, and to feel generally uncomfortable. And to have your clothing altered costs considerable. In fact it costs more to have them made over than the original price of the article. . . . If we did not have them altered for our own comfort, the officers would make you have them so for appearance sake. [83]

If the post did not have a barber, someone in the company who had some skill at the trade was able to earn fifty cents per haircut in his spare time. [84] Shaving and trimming beards and mustaches, also a part of the appearance of the soldier, was usually performed by each individual. Personal hygiene was often ignored by many soldiers because bathing facilities were limited. Private Matthews, Eighth Cavalry, provided a rare description of bathing at Fort Union in December 1870 in a letter to his folks back home:

Have just taken my Saturday evenings bath. And as feel somewhat refreshed, concluded would try and write to you. The manner in which we get a bath now reminds me of home and my little brothers. We borrow a tub from one of the Laundresses, put on a large pot of water. When it is warm enough put it in a tub and jump in. Wash yourself as well as you can in front, then get one of the boy's to wash your back. That done you step out of the tub and walk forth a cleansed man. [85]

Many of the soldiers did not attend to personal cleanliness as carefully as Private Matthews, but their clothing and bedding were regularly scrubbed by laundresses (except when they were in the field). [86] Even so, the smell of the barracks where unwashed men were crowded together in compact conditions with limited ventilation added to the unpleasantness of the lives of enlisted men. Most, however, complained more about the food they received than the scent of quarters and companions.

Most soldiers reportedly grumbled about how their rations were prepared. An example of their grievances was provided by Eddie Matthews while on a scouting expedition in 1872:

Our Cooks (kind hearted fellows) thought they would treat us to some soft bread. So last night they baked. At breakfast this morning I was handed something which from its color and weight I presumed must be part of a brick, but was told by the cook that it was my ration of bread. Now I believe my digestive organs are about as strong as the majority of the white race and I would no more attempt their powers on that piece of bread, than I would on a 12 lb solid shot. I politely thanked our gentlemanly cook, but declined eating any of his fresh bread, prefering "hard tack" which had been baked in some mechanical bakery in the first year of the late Rebellion. [87]

Matthews also testified that the soldiers did not always receive full rations as regulations required. In 1874, when his company quartermaster sergeant was shorting the enlisted men on beef and bread at Fort Union, Matthews complained to his company captain, Louis T. Morris. Captain Morris investigated the complaint and, finding it to be true, ordered the errant sergeant to see to it that full rations were issued "hereafter." Matthews, who had only six months left to serve, explained to his parents:

This is the first time during my service that I made a report of the kind. And would not have made this one, only the living was getting too bad. And as my time was getting short did not want to die of starvation at this stage of the game. The men of the Company have been praising me all day for making such a change in their living. And say had any other man in the Company made the same report very likely he would have been put in the "Guard House" and no change made after all. [88]

The quality of food issued remained much as it had been prior to the Civil War. From the war years through the early 1890s, the basic army menu included hash (comprised of meat and desiccated potatoes, sometimes with other vegetables such as onions), slumgullion stew (meat and vegetables), beans, fresh beef, hardtack, salt bacon, coffee, vinegar, molasses, and bread. Bread was baked for the garrison at the post bakery and by designated cooks when troops were in the field. [89] Fresh vegetables were provided in season by post and company gardens (gardens were cultivated at Fort Union until the post was abandoned). Occasionally dried fruits (especially apples and prunes) were issued and usually cooked for serving. As before the war, fresh milk, eggs, and butter were not issued, and company funds (raised primarily from the sale of surplus rations issued to the company) were sometimes used to purchase these when available. Other purchases with such funds included, when available, fresh fruits and vegetables, poultry, pickles, sauerkraut, raisins, and condiments. [90]

The soldiers usually were treated to special meals on holidays, a pleasant break from the usual fare. Eddie Matthews described the "elegant dinner" served to the 20 men of his company present at Fort Union on Thanksgiving Day in 1873: "Had four roast turkeys, (nice ones) none of your old Gobblers, two hams, . . . biscuits, butter, pickles, (Cucumber and Beet), Coffee, bread and for desert pudding and pies in abundance. . . . We had enough left for our supper and breakfast." [91] Matthews always expressed appreciation for good food, and he was also critical of unsavory fare.

Enlisted men, as well as officers and their families, could spend some of their pay for produce brought to the post by New Mexican farmers and gardeners. In the summer of 1870 Private Matthews reported that raspberries, apples, and peaches were available from local citizens, but he complained that the berries were expensive and the apples and peaches were small, about the "size of a plum." [92] Soldiers were also able, at their own expense, to purchase all types of food from the post sutler's store, where a wide variety of basic foods and delicacies (including sardines, canned oysters, and candy) were available. After 1866 the commissary department was authorized to supply to enlisted men as well as officers, at cost, a number of foods not issued as part of the regular ration (including such items as canned fruits, vegetables, and meats). The post sutlers generally opposed this because they considered the sale of such items to be competitive and an invasion of their monopoly trade rights. Canned tomatoes and other canned vegetables were added to the regular rations issued to the soldiers in the late 1880s. [93]

Matthews testified that many soldiers spent a portion of their pay to supplement the rations they received, and he confessed that he had "spent more money perhaps than I should have since have been in the Army." He justified what he had spent to augment the army rations of "plain and substantial food" of which "one tires," and noted that a soldier "in five years will spend considerable money for little extras which help his health and living wonderfully, and which added to his government rations one can live very well." [94]

Throughout the postwar era, as before, the quality of the food was affected by the skills of the cooks. Soon after his arrival at Fort Union in 1870, Private Eddie Matthews, was "elected for a turn in that disagreeable business" of the "Cook House" for a period of ten days. He informed his family back home that,

I am very much opposed to working in the Cook House, but under the present circumstances am better off than would be, were I in the company for duty. Out of 56 men, we have only 12 for duty. Those twelve have to go on Guard every other day, only get one night in bed [out of two]. And it will be that way for two months, and perhaps more. . . . Another advantage I have in the cook house, is I always get enough to eat. And can always make some fancy little dishes to coat the appetite. At least something better than Hard Tack, and Pork. But I must say we are living very well since we came here. In the morning have Beef Steak, Bread and Coffee. Dinner Beef, Bean Soup and Bread. Supper, Coffee, Syrup Bread and Pickles. Splendid cucumber pickles. The 1st Sergt, Quarter Master Sergt & three Cooks, mess by ourselves. We always have something extra. Such as Eggs, Milk, Butter, Bread Pudding, Doughnuts &c. How is that, don't that make your mouth water. Eggs are worth 25 cts doz., Butter 50. Beef Steak 10 cts. lb., Milk 10 cts Qt. Prices here for everything is very reasonable. Very much the same as prices in the States. So different from miserable Arizona. [95]

When he was not assigned to kitchen police, however, Private Matthews frequently complained about the quality of the meals. For example, he facetiously informed his family on Sunday, June 12, 1870, that he had "just finished devouring a sumptuous repast composed of tough roast Beef and burnt beans." [96] In April 1874 he described his dinner, which included a piece of roast beef "about the size of a small sized mouse." He continued in his typical style:

And that little piece of meat contained about as much toughness as anything of its size I ever saw, not excepting rubber. I hardly think there is a dog in the Garrison (and there are about five hundred) that could make an impression on that bit of meat. Am sure he could not eat it and live. Then I had soup, soup that would make an invalid die to look at, and a well man sick to indulge in. This soup was composed of three nearly equal parts, namely cabbage, rice and sand, if there were any perceptible difference in the equalization of the ingredients it was in favor of sand. Of course I enjoyed the soup, for desert we had dry bread, so you imagine how good I feel at the present moment. It is a singular thing that here in one of the best stock raising countries in the world we get the poorest meat. One would imagine from the toughness of the meat served up to us that we are consuming some of the old pioneer cattle that crossed the plains in 49. And I guess some of it did. [97]

Later, after serving several weeks in the field and subsisting on a diet in which the principal ingredient was beans, Matthews wrote:

When I say we have had bean soup for dinner, and baked beans for supper every day for the past month and that I have eaten heartily of them at every meal, and that I like them, I only tell the truth. Still when one has beans for about a thousand meals in succession the thing becomes monotonous and considerable on the order of sameness. And I have no doubt but that I would fight if any person said beans to me when I leave this bean bellied Army. [98]

Food was always something about which soldiers could grumble. One veteran, Sergeant George Neihaus, recalled that the food at Fort Union was "rough." He remembered that the enlisted men constantly complained about the vittles and discussed how they would redress the privations endured when they returned to civilian life. [99] Eddie Matthews frequently disclosed his plans to eat well when he returned home, often expressing his desire for a chicken dinner. After the meal of tough beef and sandy soup he described above, Matthews concluded: "If I don't make those chickens wish they had never come out of their shells when I come home, it will be because I can't run fast enough to catch them." [100]

One might conclude from the sparse accounts of enlisted men which have survived that grumbling was a major leisure-time activity of frontier soldiers. Undoubtedly, complaints (real and imagined) were common subjects of conversation. How soldiers relaxed when not on duty varied considerably, but Don Rickey derived general conclusions from his interviews with veterans active during the era of the last three decades of Fort Union history, and the records of Fort Union contribute additional details. Rickey concluded that, for the enlisted personnel, "the principal barracks relaxation was visiting and talking among themselves," which would have included the ubiquitous complaining. [101]

A popular pastime for many soldiers was playing cards in the barracks, at the post trader's store, or at saloons and other places off the military reservation. Some card games involved betting and others simply provided entertainment and an atmosphere for affable conversation. Popular games without stakes included euchre, cribbage, casino, and pinochle. Whist was enjoyed by a few enlisted men, but it was a game more common among officers and their wives. The favorite gambling card games were stud and draw poker, three-card monte, and black jack. Although all forms of gambling were prohibited among soldiers, Rickey noted that some soldiers regularly "squandered all their pay in gambling." In addition to cards, dice were sometimes used for betting. Horse racing was popular among soldiers and frequently involved wagers. Despite the ban on all gambling, Rickey found that "the average low-stake barrack room games, however, were usually not rigidly policed." [102]

A rare mention of gambling at Fort Union appeared in the post records for 1886, when Post Commander Henry R. Mizner issued an order declaring that all types of gambling were prohibited "among the enlisted men." [103] It may be assumed that the order was a response to information that there was widespread gambling among the troops. The order was probably ineffectual. Aubrey Lippincott, who spent part of his youth at Fort Union as the son of the post surgeon, 1887-1891, recalled many years later that "there was always gambling." [104]

|

| Horseback riding was a popular pastime at Fort Union, especially for officers and their families. Here an unidentified couple, officer and woman, are on the bluffs west of the post, which is barely visible in the background. Photo Collection, Fort Union National Monument, courtesy B. William Henry. |

The soldiers also engaged in many other types of recreational activities. Rickey noted the growing importance of athletic contests after the Civil War, including "foot racing, jumping, weight-throwing, horseshoe pitching, and field sports." Baseball became one of the most popular sports in the 1870s and 1880s. [105] Other sports included boxing, horse racing (a race track was built at Fort Union in the late 1870s), lawn tennis, [106] billiards (billiard tables for officers and enlisted men were available at the post trader's store at Fort Union soon after the Civil War), bowling (Adolph Griesinger built a bowling alley in connection with his restaurant in 1868), [107] hunting, and fishing. Hunting was popular throughout the history of the post. Second Lieutenant Duncan recalled of his time at Fort Union, "I spent much of my time on horseback, hunting and riding over the country, not a fence impeded progress in any direction." [108] There was at least one sleigh at Fort Union in the winter of 1873-1874, apparently used by officers and their families for pleasure trips. [109]

A soldier-correspondent at Fort Union in the late 1880s wrote in an area newspaper that entertainment at the post included good trout fishing, duck hunting, band concerts, theater, and visits to Loma Parda, Tiptonville, and the hot springs near Las Vegas. [110] In the 1880s bicycling became a popular pastime for a few people at the post. Additional forms of recreation included dominoes, chess, checkers, practical jokes, story telling, and humorous tales. Some of the officers and their families played croquet. [111] Other diversions included singing, musical instruments (banjo, guitar, violin, and harmonica), variety shows, minstrel shows, and dances.

|

|

| Musician Philip Herrier, Third Cavalry band at Fort Union, about 1807. Photo Collection, Fort Union National Monument, courtesy of Grace Winterton. | Private C. E. Borden, Tenth infantry bands man at Fort Union, about 1887. J. R. Riddle photo, courtesy Kansas State Historical Society. |

Almost everyone who wrote about life at Fort Union, including enlisted men and officers' wives, testified to the popularity of dances. In February 1873 Sergeant Eddie Matthews, Eighth Cavalry, noted that there had been four "grand balls" at the post during the winter. Three of those had been hosted by three companies of his regiment, respectively, and the other was sponsored by the Good Templars, in which Matthews was an active leader. [112] In November 1873 the Good Templars sponsored a dance the night before Thanksgiving. Matthews reported the details to his family.

Had our Hall decorated very nicely with Flags and pictures. At 8:30 nearly all the Officers and Ladies of the Post came in and opened the Ball for us, they danced one Quaddrill and one Waltz, thanked us for the pleasure and departed. Soon as they made their exit, dancing commenced in earnest and was kept up until 12. Lunch in abundance consisting of Bread, Biscuits, butter, Ham, tea, Coffee, Cake, Lemonade, Candy and Cigars to wind up with was then served. One hour was very pleasantly spent in that kind of pastime and then dancing resumed and kept up until 6 A.M. . . . Thirteen ladies (nearly all married) and about three times that many men composed the party. And I must say it was the most pleasant little party I have seen since leaving home. [113]

|

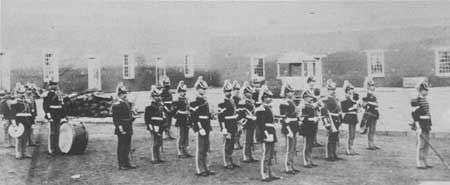

| Twenty-Third infantry band at Fort Union, 1883, courtesy Fort Sam Houston Museum, Department of the Army. |

The Good Templars sponsored another dance on New Year's Eve, December 31, 1873. Matthews attested, "We had a real delightful time." He again provided details:

Danced from 8 to 12 M and then got on the outside of a good substantial supper. At 1 A.M. resumed hostilities and kept it up until 5 A.M. I don't think there was one in the Hall that night but what enjoyed him or herself, and I guess they all felt like me: "tired but satisfied". I was quite an important individual in the affair, was one of the Committee on Invitations, Music, and the only Floor Manager we had, besides served as Head Waiter at Supper, and in fact made myself generally useful. [114]

Music for dances was usually provided by the post band. The presence of an army band at any post was a source of entertainment for enlisted men as well as officers and their families. After the Civil War Fort Union was fortunate to have a regimental band assigned to the garrison much of the time. The bands played regularly at the post, provided music for dances and special occasions (such as weddings, welcome and farewell parties, birthday parties, and holiday festivities), and frequently gave concerts in outlying communities. In 1870 the Eighth Cavalry band from Fort Union performed for the July 4 celebration in Las Vegas. A few weeks later ten additional bandsmen and a new band leader joined the regimental band at Fort Union. Private Matthews exclaimed, "We have much better music now." [115] A few years later the Ninth Cavalry band, at that time stationed at Fort Union, presented a Fourth of July concert in Santa Fe in 1876, the centennial of American independence. A permanent bandstand was erected at the post in 1876 (there may have been temporary bandstands earlier), and weekly concerts (held inside when the weather was intemperate) were popular with enlisted men, officers and their families, and civilians. After the railroad was available for transportation, the bandsmen were invited to play for dances and other diversions in communities as far away as Denver to the north and Albuquerque to the south. The Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway acquired the resort hotel at the hot springs near Las Vegas in the early 1880s, and the band was repeatedly invited to perform there for tourists and health-seekers. The musicians provided a popular form of entertainment on and off the post. [116]

|

The resourcefulness of enlisted men in providing their own entertainment at the post blossomed forth in various types of dramatic presentations, ranging from comedy to serious drama. In 1870 Private Matthews, Eighth Cavalry, noted that some members of his and another company of the regiment had presented "a Variety Theatre performance here a few nights ago." He observed they had "done very well, they took in about one hundred dollars." The participants planned "to have a performance once a week," but Matthews, who did not want to spend his austere pay for entertainment, declared, "Don't think I shall go soon again." He went one more time, however, and concluded not to go again because "the performance is very poor." [117] The officers usually encouraged play acting and occasionally joined in the act. Sometimes the actors organized a dramatic club and sometimes a group of volunteers would present a program without a formal association. Now and then a traveling show would perform at the post. The plays, regardless the sponsors and the talents of the players, were usually enjoyed by residents at the post. Once in awhile, during the latter years of Fort Union, enlisted men gave performances in nearby communities, especially Las Vegas.

In 1883 the Fort Union Dramatic Club, assisted by the Twenty-Third Infantry band stationed at the post, presented a two-night variety show in Las Vegas to raise funds for the post school. Tickets were 75 cents for reserved seats and 50 cents for general admission. After each show the band played for a dance. In 1885 the Club gave a performance of a melodrama titled "Ben Bolt" to a standing-room-only audience. Another group of enlisted men organized the Fort Union Comedy Company (later Fort Union Minstrel Troupe) which also performed in Las Vegas as well as at the post. [118] The Fort Union Minstrel Troupe was active and popular in 1888, giving performances at the post library on Monday evenings. [119]