|

FORT VANCOUVER

The Administrative History of Fort Vancouver National Historic Site |

|

Chapter Four:

SITE PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT AT FORT VANCOUVER

INTRODUCTION

Legislation made possible the creation and eventual expansion of Fort Vancouver National Historic Site. But, once established, a site needs guidance to fulfill its potential; site planning and development bring a park concept to fruition and set goals for future management and interpretative programs. The general direction of planning for Fort Vancouver has changed dramatically over the past 45 years. From preserving the archaeological record to commemorating the fur trade and its cultural importance, to reconstructing the physical structures to present the public with a tangible piece of the "past," the Park Service has compromised some of their more restrictive policies towards reconstruction in order to develop the Fort Vancouver site.

LAND ACQUISITION AND ITS EFFECTS ON FORT VANCOUVER

A major component of the planning at Fort Vancouver revolved around land acquisition. After the initial 60-acre acquisition which established Fort Vancouver National Monument, the Park Service and local Vancouver supporters quickly realized that more land was needed to preserve the historic record. In the summer and fall of 1954, the commanding officer at Vancouver Barracks advised Superintendent Frank Hjort that the Army might declare 5.8 acres west of the fort site, which contained part of the historic Kanaka Village, surplus property. This property held one of the more important archaeological sites. John Hussey, Park Service regional historian, urged the Park Service to keep its options open to buy the property, but the Army was not yet ready to part with it. [1]

Two other parcels, however, were transferred to the Park Service within the first decade of Fort Vancouver's existence. The General Services Administration released 6.5 acres of river tract lying between the City of Vancouver's Kaiser access road (Columbia Way) and the Columbia River to the National Park Service. The City of Vancouver had also been interested in this tract of land for development as a park, but did not have the funds to purchase it and could not assure the Park Service that the land would remain undeveloped under its ownership. Also in January 1958, the GSA asked the Park Service to administer a 100-foot-wide railroad right-of-way just north of the Kaiser access road. Together, these two parcels totaled 14.8 acres and were added to Fort Vancouver National Monument by a departmental order "enlarging" Fort Vancouver, which was published in the Federal Register January 23, 1958. [2] These tracts of land assured that the scenic view from the monument to the historic riverfront would be preserved.

Two years later, the Army again prepared to release land at the Kanaka Village site to the National Park Service, but only if the Civil Air Patrol had adequate hangar space for planes at an alternate site. [3] The Fort Vancouver Historical Society (originally the Fort Vancouver Restoration and Historical Society) donated $50 toward the move to make room for monument expansion. The society also offered to donate the proceeds from a salmon bake for the purpose. [4]

MISSION 66 planning also anticipated acquisition of more Army property including several historic roads, the Hudson's Bay Company cemetery, and all of the city-owned Pearson airfield. [5] But Fort Vancouver National Monument was limited to 90 acres as set by Congress, and only after the legislation of 1961 expanded the ultimate boundary and changed the designation from monument to national historic site did the acquisition of the Kanaka Village and other related property become possible.

Indeed, by November 1962, the Army declared part of the Kanaka Village property surplus and the Park Service acquired 14.5 acres the following spring. The property included nearly half of the village site and old orchard "where the Hawaiian, Indian, and Canadian engagees of the Company lived," wrote Superintendent Frank Hjort. "Second to the fort site, this is the most important area associated with the Company's Vancouver establishment." [6] The land, however, was subject to an Army Aircraft Taxiway easement, which gave the Army unobstructed access from Vancouver Barracks to Pearson Airpark. The National Park Service received the property from the secretary of the Army, which brought the total area of Fort Vancouver National Historic Site to 89.123 acres in June 1963. [7]

In the late 1960s, the Park Service entered an era of wheeling and dealing for land at Fort Vancouver. Commercial development, freeway expansion, and the continued encroachment of Pearson Airpark put pressure on the site to actively pursue control over surrounding land uses. The proposed highway interchange was especially ominous. John Rutter, the regional director, feared that it would permanently obscure the western portion of Kanaka Village, leaving "no opportunity to carry out existing plans to interpret the village within the present boundaries by reconstruction of fences, marking house sites, erection of exhibits, etc." [8]

The regional director proposed that the Army give the Park Service a large parcel of land between Kanaka Village and the freeway where the interchange was going to be built. The Park Service would then trade a portion of the tract to the State Highway Commission for a strip of state-owned right-of-way at the southern end of Pearson field. In addition, the Army would give the Park Service a large tract of land southwest of the parade ground which encompassed the Hudson's Bay Company cemetery in exchange for the continued use of the western portion of the parade ground.

Needless to say, these land exchanges never occurred. However, since the Army land nearest the proposed interchange was part of the park's ultimate boundaries, the Highway Department negotiated with the Park Service to provide "improved access to the Historic Site together with adequate directional signs" in exchange for putting the interchange over the westernmost portion of Kanaka Village. [9] The Washington State Highway Commission was even able to mitigate extensive damage to the site. Its study, S.R. 14 Interchange on Interstate Highway No. 5 and Fort Vancouver National Historic Site, required only 0.7 acres of land from the historical site. By May 1969, the Army, the Highway Department, and the Park Service agreed on "Alternate Plan No. 1," which moved the ramp out of the middle of the Kanaka Village area and provided a screen of trees, shrubbery, or fencing to be "placed to preserve and compliment the environment of the Historic Site. The interchange and freeway would become a green park-like transition zone between the historic setting of the year 1845, and the modern urban business district of today." [10] After the National Park Service purchased Pearson Airpark in 1972, the Park Service was able to trade 1.63 acres to the Washington State Department of Highways in exchange for 2.5 acres south of Pearson Airpark. The state was then able to construct the new SR 14 interchange on Interstate 5. [11]

Another important land acquisition considered by the Park Service was a 30-acre tract of Veterans Administration property to the north of Fort Vancouver. In April 1969 the Park Service requested the 30 acres in hopes of negotiating a future trade with the city for Pearson Airpark and the 5th Street right-of-way. But both Clark College and the city had an interest in the site: the city for a golf course and the College for expanding its facilities. [12] With the city uninterested in a swap for the Pearson property, the Park Service eventually withdrew its request for the 30 acres of Veterans Administration land.

Despite the importance of the exchange of highway property or the negotiating value of the Veterans Administration property, the 70 acres of Pearson Airpark property remained the highest priority for acquisition at Fort Vancouver. After years of negotiations with the City of Vancouver (which are detailed in Chapter Six of this report), the National Park Service purchased 72.57 acres of land that the Airpark occupied for $544,500. The city was limited to 30 more years of airport use by provisions in the Statutory Warranty Deed which would allow the Park Service to incorporate the land into its plans for Fort Vancouver development. The new land also expanded the size of Fort Vancouver National Historic Site to about 161 acres.

In February 1973 the Park Service petitioned the City of Vancouver to vacate 40 feet of East Reserve Street between Evergreen Boulevard and East 5th Street in order to expand existing utility and maintenance facilities. [13] On March 21, 1973, Alan Harvey, the city manager, recommended that the City Council approve the street vacation, and City Ordinance No. M-1399 of April 13, 1973, granted the vacation, except an easement for "the construction, repair and maintenance of public utilities and services." [14] On May 6, 1973, the vacation of .46 acres of city right-of-way on East Reserve Street to the National Park Service was official. Owning the vacated portion of the street allowed Fort Vancouver to "construct an addition to our maintenance facility and build a covered picnic shelter adjacent to our present visitor center." [15]

Besides Pearson Airpark, the waterfront property had great significance to the development of Fort Vancouver. The Park Service had acquired a long strip of waterfront property in 1958, but in the spring of 1974 the Park Service requested 2.1 acres of old Coast Guard property which had once contained the historic boat landing and Hudson's Bay Company salmon house. [16] The following spring Edward J. Kurtz, the acting regional director, resubmitted the request for the transfer of the Coast Guard Depot property, with "a proposed five-year program for restoration of the historic scene at the waterfront." [17] In July 1975, the abandoned Coast Guard Station was finally transferred to Fort Vancouver National Historic Site. The station and pier were torn down and the National Park Service prepared a special use agreement with the city, and planning for the property was incorporated into the city's Waterfront Park development. [18]

|

| Land Transaction and Ownership Map (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

In April 1980, Superintendent James M. Thomson helped prepare the "Fort Vancouver National Historic Site Land Acquisition Plan," which in conjunction with the 1978 Master Plan identified priorities for future land acquisitions. The plan targeted the 14-acre parcel of Army land west of the historic Kanaka Village which John Rutter had wanted in 1969 and three to four acres of City right-of-way on 5th Street. The western land would allow the park to explore and excavate Kanaka Village further and the street right-of-way would allow the restoration of historic roadways and historic scene, integrating the fort site with the Visitor Center and parade ground. [19]

Though Fort Vancouver National Historic Site has not acquired any new property since 1975, it continues to plan for the future development within its ultimate boundaries. It is unknown how the proposal for an Historic Reserve in Vancouver will specifically affect the land acquisition program at Fort Vancouver.

MASTER PLANS AND BOUNDARY STUDIES

Early Development of the Monument

After Fort Vancouver National Monument was authorized in June 1948, O.A. Tomlinson, Park Service Region IV director, assigned Regional Historian Aubrey Neasham the task of putting together a preliminary development program. [20] With the encouragement and help of the Oregon Historical Society, Neasham and Louis Caywood worked with locals to raise funds for the monument, while John A. Hussey, who worked under Neasham, prepared a preliminary outline for development at the monument.

Though Representative Russell Mack and local supporters had envisioned complete reconstruction of the old fort, Park Service personnel did not agree on the best direction for development at the site. In particular, the regional director opposed reconstruction of the fort. In November 1948, he wrote a local member of the Knights of Columbus that, "It is not the plan of this Service to `re-establish a replica of the site of Old Fort Vancouver.' No doubt most of the existing buildings will be removed and the area returned to its natural condition." [21]

Other local interests, such as the mayor of Vancouver and City Council, were more interested in combining the development at Fort Vancouver with the needs of the city. In October 1948, Mayor Verne Anderson wrote Regional Director Tomlinson, to ascertain what lands the Park Service considered part of the monument and whether the city could coordinate planning. [22] Park Planner Harold G. Fowler and Louis Caywood met with Mayor Anderson, Donald Stewart, a local architect, and other consultants and city planners only to discover that the city planned "to sound out the possibility of designing [a] civic center, in conjunction with Fort Vancouver National Monument, allowing the civic center to be all or partly within the proposed boundary of the monument." [23] The city's plan set the tone for its continued relationship with Fort Vancouver. The Park Service felt pressure to fully use its property and provide visible signs of site development or risk the criticism and possible encroachment of the city.

Dr. John Hussey finished the first "Preliminary tentative outline" for Fort Vancouver National Monument in December 1948. Though Louis Caywood had located the fort site, the Park Service had not yet determined how to interpret the landscape and cultural artifacts found during excavation. Hussey's tentative plan for development of the National Monument called for a main museum building located at a commanding position, with an "orientation parapet" that overlooked the original fort site. The fort would be "simply marked" on the four corners; the original building sites would be similarly treated. The museum room would house exhibit cases, dioramas, and murals depicting the life and economy of Fort Vancouver during the mid-19th century. The approximate cost would be $43,900 for the exhibits and museum interior. Hussey thought that a planting of Douglas fir around the perimeter could help isolate the monument from "unrelated modern buildings" already crowding the surrounding landscape. [24]

Though the Park Service plans precluded recreating the original fort, Burt Brown Barker of the Oregon Historical Society and the Fort Vancouver Restoration and Historical Society still favored reconstruction and requested that Congressman Russell Mack study the matter. Though Mack had openly supported the idea, by early 1949 he was unable to find any precedent for reconstruction of lost historic structures by the federal government. "Unless I can find such a precedent and thereby be able to say `you did it before why not do the same thing again at Vancouver,'" Mack informed Donald Stewart, "I'm going to have difficulty in selling the restoration of Fort Vancouver idea to Congress." He suggested that the Historical Society instead look to the State Parks Department for funding since the "Park Service is cool to the idea of restoration of the old fort, preferring instead to build a cyclorama building and a museum." [25]

Indeed, lack of funding was one of the major deterrents to development at Fort Vancouver. During 1949, Fort Vancouver only had a $3,635 budget, barely enough to maintain Caywood's administration of the site. [26] In July 1949, Acting Director Hillory A. Tolson solicited Senator Warren Magnuson to support the appropriation of $25,000 for the 1950 fiscal year to operate Fort Vancouver. Yet, Hussey's development plan for Fort Vancouver estimated a cost ten times that amount to construct roads and improve the grounds of the monument. [27] And there was disagreement over how the funding would be spent. Some local supporters of the monument still did not want to limit the site simply to archaeological excavation and a museum. Burt Brown Barker complained to congressional members that the Park Service

frowns on reconstructing the fort and yet ask for $250,000 for buildings. What could that be if not for reconstruction. They talk of a museum. Heavens, the reconstructed fort would be the museum and they should have the museum in the fort. We can see no sense to building a museum at great expense and not reconstructing the fort. Visitors want to see reproductions--not museum buildings. [28]

Barker was not opposed to completing the archaeological work, but his words seem prophetic in predicting public tastes.

Not only did the public clamor for particular plans for the site, but restrictions and political pressures on the use of the site strongly influenced development plans at Fort Vancouver. For instance, an aircraft easement over the fort site limited interpretation possibilities. In 1950, the Park Service planned to simply mark the corners of the stockade with flat cement markers since visitors could not walk onto the site. The City of Vancouver had always asked that the fort be developed as a "Real Tourist Attraction," as one editorial headline demanded. The city was encouraged that the monument would make Vancouver "the archaeological center of the park service's activities in the northwest, and possibly on the Pacific coast." [29]

The new estimate for the construction of a museum at Fort Vancouver was $150,000 in 1950. Another $50,000 was needed for the superintendent and employee residences and utility buildings. Despite local enthusiasm and support from Representative Russell Mack, Congress only appropriated a small amount to clean and grade the monument grounds, paint buildings, and repair and maintain existing buildings. Indeed, an old Army building at the south end of the parade ground had been slated as a temporary museum and administration building. The Army had just rehabilitated offices, class rooms, and a storage area, which Louis Caywood used as a center for his excavation work. [30]

When the first superintendent, Frank Hjort, came on board in early 1951, local supporters increased pressure to restore Fort Vancouver. But the regional office remained reticent. In November, the regional historian, Aubrey Neasham, visited the site and advised Frank Hjort since no funds had been programmed for a reconstruction project and their research was not even complete, that the Park Service would favor

an interpretative type of museum at the Monument rather than a full reconstruction of the stockade area. Before encouraging reconstruction projects, although they may have a real educational value, this Service should be sure as to what we wish to advocate. We are somewhat of a model in the State of Washington and what we do may be closely followed by State and local organizations. [31]

Developing the Landscape

Though the early debate on reconstruction at Fort Vancouver reached an impasse with the Park Service tenuously upholding their preservation policy, the overall site still needed to be developed; the Park Service needed to show a good faith-effort to the community to keep the momentum going.

The first Master Plan Development Outline for Fort Vancouver National Monument, written under Frank Hjort in 1952, conceived a buffer zone around the fort site to protect its historic integrity. [32] Land acquisition and landscaping were important parts of creating the proposed buffer zone. In the summer of 1951, Superintendent Hjort informed the regional director that the Fort Vancouver Restoration and Historical Society had "very generously offered through several garden clubs located in this vicinity to furnish the shrubbery and plants necessary for landscaping some of our area in the event we can go ahead with the planning." [33] The regional office skeptically replied that "It would seem undesirable for you to accept plant materials indiscriminately for landscaping the grounds; however, there is no objection to your accepting plant materials such as may be specified on planting plans prepared by this office." [34]

But, no plan was forthcoming. The regional landscape architect estimated that landscape development would cost Fort Vancouver about $10,000. The estimate included landscaping the planned museum, monument grounds, residences, and utility area, as well as marking the location of buildings and other features at the fort site. [35] Again, lack of funding put landscaping plans of the early 1950s on hold. Instead, Hjort was content to make an inventory of the existing landscape features, showing the size, species, and location of vegetation, which might facilitate future landscaping plans prepared by the regional office. [36]

The First Boundary Study of 1954-55

Some of the individuals who helped secure the initial legislation to establish the park were disappointed by the boundaries of the original monument. Burt Brown Barker, of the Oregon Historical Society, wrote Region IV Director O.A. Tomlinson that he was "keenly interested" in the Kanaka Village site west of the Fort Vancouver stockade. Indeed, he insisted that the "village, historically, and I suspect archaeologically, is as important as the fort. The fort represented one part of the life only, that of the gentlemen. The village represented the servants and other workmen's quarters." [37]

Dr. Barker's persistence paid off. By the fall of 1953 he had lit a fire under Senator Wayne Morse of Oregon, who contacted National Park Service Director Conrad L. Wirth to emphasize the importance of the Kanaka Village area. Barker prompted the director's office to suggest that the regional office prepare "a study of the boundaries of Fort Vancouver to determine the ultimate ideal boundaries and to assemble historical data which could be used by the Service as justification for the acquisition of needed lands as they become available." [38] And so the Park Service authorized the first boundary study of Fort Vancouver National Monument.

The irony was soon apparent. The 90-acre limitation legislated by Congress in 1948 had quickly become obsolete. In February 1954, Lawrence C. Merriam, the new Region IV director, asked the superintendent what his priorities were for Fort Vancouver land acquisition and ultimate boundaries. Frank Hjort ranked the surrounding parcels as follows: Priority "A", 70.92 acres which covered some Pearson Airpark land, but also land to the west of the fort site; "B", a 9.31 acre triangular piece which included part of Kanaka Village and spur railroad track east of the fort site; "C", a 12.68 acre strip east of the fort site, which encompassed two Hudson's Bay Company road paths; "D", 19.09 acres southwest of the parade ground which included most of the cemetery and several other minor structures; "E", 22.17 acres divided between two parcels on the extreme west and extreme east of the ultimate boundary; and lastly "F", 14.14 acres that included Officers' Row. These parcel configurations were very different than later master plan acquisition maps because they were not based on single owner parcels, but on proximity to the stockade site and importance to the cultural landscape. The total acreage within the proposed ultimate boundary encompassed about 209.74 acres, so Regional Director Merriam suggested that legislation to increase the size of the present monument place a 220-acre limitation on the site. [39]

John Hussey drafted a report to support the proposed ultimate boundary. In the May 1954 report, Hussey insisted that the 90-acre limitation for the monument was

entirely inadequate for the proper preservation and interpretation of the area's historical values. This situation is not critical at the present moment, because the present use of the adjacent land as a military reservation and airport tends to preserve the character of the landscape, which, in essence, has changed remarkably little since Hudson's Bay days.

Yet, the Park Service feared that the surrounding property might soon be used for commercial purposes which would destroy the historic scene and obscure the relationship of the fort to the river "even from the elevated situation of the Monument headquarters and interpretive center." [40]

Conrad Wirth, the National Park Service director, generally agreed with Hussey's assessment. Further, he realized that Fort Vancouver, in light of its location on prime real estate, had to be prepared to show the community how it would use the additional land at the monument. [41] However, the Park Service's initial request for secretarial approval of the ultimate boundary report met a brick wall of opposition. The secretary of the Interior quickly returned an October 4, 1954 memo from the National Park Service director marked "not approved, orig. destroyed." Secretary Douglas McKay wondered what circumstances brought about the 90-acre limit in the first place and why the Park Service would want to change its mind at this time. Even after investigation, the Park Service could "find nothing in the legislative history of the act to indicate why Congress reduced the limitation from 125 to 90 acres, but the committee report on the bill states that it was with the consent of this Service." [42]

1961 Legislation - Fort Vancouver National Historic Site

On January 16, 1955, Secretary McKay finally approved the proposed boundary study for Fort Vancouver as a general planning objective. He then asked Senator Guy Cordon to seek legislation which would extend the site boundaries to the ideal limit. An additional 136 acres would be added to provide a clear view of the Columbia River and to include important areas adjacent to the fort such as Kanaka Village and the Hudson's Bay Company cemetery. Yet, it was Representative Russell Mack of Washington's Third District who on July 1, 1958, first introduced a bill requesting that the acreage limitation at Fort Vancouver National Monument be increased by 130 acres. The proposed legislation also meant to redesignate the monument as Fort Vancouver National Historic Site. [43]

The Fort Vancouver bill floundered for several years and Mack's untimely death in 1960 might have been the end of it, but Representative Julia Butler Hansen, elected to fill Mack's seat, made it her priority to get the legislation passed. On June 30, 1961, the bill passed, increasing the maximum size of Fort Vancouver to 220 acres, allowing acquisition of nonfederal lands within the revised boundaries based on the 1955 boundary study, and designating Fort Vancouver a national historic site. The new designation gave Fort Vancouver higher visibility--perhaps even more clout--in local political struggles and opened the way for a change of direction in development and planning.

MISSION 66 Planning

The 1955 boundary study not only served as a basis for new legislation, but it also inspired much of the planning behind the MISSION 66 program for Fort Vancouver. MISSION 66 was a 10-year program to develop the park system to its fullest potential by 1966, in time for the 50th anniversary of the National Park Service. The Park Service estimated some 80 million visitors traveled to the parks annually by that time and wanted to provide adequate and modern facilities at all the units of the system.

At Fort Vancouver, the MISSION 66 Master Plan, prepared by the superintendent and other staff members, contemplated new visitor facilities and resurrected the debate on reconstruction. The debate in the early 1950s focused on whether or not to reconstruct. The National Park Service felt it was not in the business of running theme parks, but, since Fort Vancouver had no visible remains left from the historic period, it felt the site needed to provide some sense of the historic scene. Indeed, by 1959 the public complained that the Park Service had been dragging its feet on the basic construction of a museum and visitor's center for Fort Vancouver. The Vancouver Columbian complained that the city was "very disappointed in the lack of progress being exhibited in developing the Monument. The National Park Service is giving Fort Vancouver the `runaround,' if you ask us." [44]

Between 1952 and 1964 Fort Vancouver staff wrote a Master Plan for the Preservation and Use of Fort Vancouver National Monument, Mission 66 Edition. The plan identified the site itself and the "great wealth of material objects [which] have been recovered through archaeological investigations" as the most significant resource of the monument. The plan envisioned a monument whose focus was on research, an interpretive theme which encompassed the fur trade and settlement of the Northwest, and an interpretive method which would principally be "self-guiding, employing the visitor center for initial orientation and to prepare the visitor for interpretive excursions over the historic grounds." Land acquisition as suggested in the 1955 boundary study, rather than reconstruction, was the most important step in site interpretation. In fact, the Master Plan only cautiously speculated that if reconstruction occurred, the structures "shall be clearly distinguished as only replicas of the original Fort Vancouver structures." [45] The MISSION 66 Plan, however, encouraged historical research which might contribute to authentic restoration and reconstruction. [46]

It was the 1961 legislation supported by Representative Hansen which finally opened the door to change. Not only did it allow for the MISSION 66 building program to continue, including a Visitor Center, housing for employees, and maintenance buildings, but the expanded boundary and more serious designation as national historic site broadened the opportunity for funding at Ft. Vancouver. Yet, despite new plans for visitor facilities, the fort site remained full of asphalt pads. As Frank Hjort, the superintendent, remarked to the regional director, "The existing flat markers are not impressive as they leave quite a bit to the imagination." He hinted that "two hundred feet of stockade wall east of the bastion [would] make an excellent backdrop for the newly planted orchard." [47]

But the Park Service was still hesitant to plan for reconstruction of the fort. Even after the City modified the avigation easement over the fort site in February 1962, freeing some of the restrictions on its use, Regional Director Lawrence C. Merriam told Hjort that he was reluctant to schedule the stockade reconstruction right away. He took a wait-and-see attitude, hoping that the new museum would take care of interpretive and educational needs. [48]

|

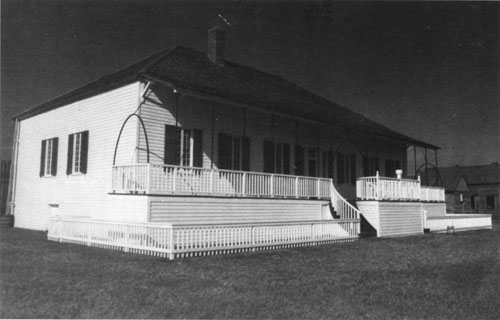

| The legislation which created Fort Vancouver National Historic Site in 1961 also provided funding for the MISSION 66 building program, including the Visitor Center, which was dedicated March 18, 1962. (National Park Service) |

Revising the Boundary Status Report

Due to the growing public demand for the reconstruction of the original stockade, Lawrence Merriam, who had initially rejected the idea, agreed in July 1962 to "a partial reconstruction of the Fort Vancouver stockade, including the northwest bastion." [49] Since the city had already modified the avigation easement over the fort site which had precluded even basic reconstruction, the Park Service was now receptive to reconstruction. But it was still not forthcoming with funding and interested local organizations started looking for private sources of funding.

By September 1963, the Vancouver Chamber of Commerce told Hjort's replacement, Superintendent Harold Edwards, that it wanted "to restore our fort site according to NPS plans and specifications by providing required materials and labor at no cost to the government." [50] Private funds would be solicited from the public and local civic groups. Park Service Architect Charles Pope recommended rebuilding portions of the stockade to which the regional director had agreed. But reconstruction was no cheap proposition. Park Service Director George Hartzog, in a letter to Representative Julia Butler Hansen in February 1965, assured her that "we fully intend to carry out this reconstruction if funds for the purpose are provided in the 1966 appropriations." And costly it was. In 1965 dollars, the estimate for total reconstruction of the stockade and the buildings within was $1 to $2 million. [51]

There were some members of the public who had mixed feelings about the reconstruction of Fort Vancouver. At City Hall, for instance, the mayor and City Council anticipated increased controversy and problems if the Park Service reconstructed the fort, since the avigation easement had not been removed from the site. [52] Indeed, newly appointed Regional Director Edward A. Hummel raised "grave questions of practicability and feasibility" of the reconstruction project in September 1965, in light of the continued existence of an avigation easement (albeit modified) over the fort site. The Western Regional Office finally decided on a compromise: it was "desirable to have the bastion project approved so that reconstruction can go ahead should avigation easement limits permit construction on the original bastion site and should it be considered desirable to reconstruct the blockhouse in lieu of part of the palisade." [53]

During the mid-1960s a new boundary study was conducted for Fort Vancouver. It is unclear exactly why the Park Service ordered the study since the 1955 boundary study had identified those surrounding properties most important to restoring Fort Vancouver's cultural landscape. Perhaps it emerged from the pressure to reconstruct the fort and the city's uneasiness with the various plans being discussed. Indeed, no overall master plan existed for the site and "no Master Plan study of Fort Vancouver is scheduled for the near future," wrote the regional director in June 1966. "Because of the uncertain status of the Army, Veterans Administration, and airport lands adjoining the existing boundaries, we believe it important that we be able to take prompt action should additional lands become available, and for such action an approved future boundary is a prerequisite." [54]

Superintendent Eliot Davis, Harold Edwards' replacement, had submitted his recommended ultimate boundaries to the regional office the previous February and urged quick approval by the national director. Yet, once again, the Vancouver community had mixed reactions to the study. Regional Director Edward Hummel lamented that

a large portion of the land within our proposed ultimate boundaries has already been zoned by the City of Vancouver as `light industrial,' and should this land become surplus (as could happen at any moment) there would be strong local pressure exerted to have this property turned over to the city for commercial use instead of going to the National Park Service. [55]

After many months of study and land surveys, the Western Regional Office approved the Boundary Status Report on October 21, 1966, which recommended the acquisition of 122.43 additional acres in 7 separate tracts for expansion of the site. At that time, Fort Vancouver National Historic Site covered 89.10 acres. Unlike the 1955 boundary study, the new recommendations did not include Officers' Row, but did include additional land along the Columbia River, some of which had been acquired by Fort Vancouver in 1958. The status report justified the addition of 122 acres to the site in order to preserve those areas important to the historic Fort Vancouver complex, but outside the immediate environs of the stockade, especially "the essential relationship between the fort and the Columbia River." [56]

Ironically, the Washington Office never approved the new Boundary Status Report, even though it seemed to simply reiterate the well-established purpose and priorities of Fort Vancouver National Historic Site. The reasons for the delay appeared technical rather than substantive. For instance, in April 1967, the Division of New Area Studies and Master Planning chief, Russell E. Dickenson, told the regional director that several of the tracts had wrong legal descriptions. [57] For Fort Vancouver, the approval of the Boundary Status Report became even more important because of the city's continually changing plans for the use of its own land. The Park Service feared that the city would abandon the airport and use the property for industrial development despite the restrictions placed on the property by its original deed. And the city might further develop the Airpark property. Eliot Davis learned in 1968 that the City Airport Committee had made an official request to the Army for the property southwest of the parade ground, which encompassed the Hudson's Bay Company cemetery, if it ever became surplus. The city wanted to build a motel, gas station, swimming pool, and restaurant for Airpark passengers and pilots. If the freeway interchange was built, the Airport Committee would instead move the concessions "to the south side of the main runway at a point approximately south of [Fort Vancouver's] Visitor Center." [58]

As late as March 25, 1968, Eliot Davis complained that "Our ultimate boundary proposal is still in the Washington Office unapproved." [59] But by this time, a comprehensive master plan was in the works, and the urgency to clarify Fort Vancouver's ultimate boundaries had diminished.

The 1969 Master Plan

The first glimmer of master planning after the MISSION 66 construction came in 1964, under the brief administration of Harold Edwards. In 1964, Superintendent Edwards helped prepare the "Draft Master Plan of Fort Vancouver National Historic Site." Edwards planned to rebuild the stockade and buildings, as well as graze oxen and herds of cattle in restored pastures to help the visitor visualize the conditions of 1845. [60] To accommodate his plan, however, Edwards recommended purchasing the eastern half of Pearson Airpark, owned by the Spokane, Portland, & Seattle Railroad, and giving it to the City of Vancouver in exchange for a release of the avigation restrictions over the fort site. [61]

As new Superintendent Eliot Davis dealt with the ramifications of the "Edwards Plan" in 1965, and the City of Vancouver's increased expectations, he recognized the need for a more permanent planning document. Indeed, without an approved boundary study, it became imperative that a master plan be prepared to clarify the goals for land acquisition within Fort Vancouver National Historic Site. With some assistance from Congresswoman Julia Butler Hansen, Fort Vancouver completed a preliminary draft of the master plan in March 1968. The plan brought together a comprehensive evaluation of park goals, cultural resources, land use and facilities, as well as the feasibility of future development at the national historic site. It created a firm basis for the reconstruction of the stockade buildings and the next phase of archaeological excavations.

The plan reiterated the prime directive of the park: "to preserve as a national monument the site of the original Hudson's Bay stockade [of Fort Vancouver] and sufficient surrounding land to preserve the historical features of the area" for the benefit of the public. For the first time, the Master Plan saw the clear interpretation of fur trade "HISTORY" as Fort Vancouver's primary goal, and archaeology as secondary, though "an integral part of the historical resource." [62]

The plan even called for recreation of "the original surrounding forest environment which has virtually been eliminated since historic times." Not only would Fort Vancouver restore the cultivated fields around the stockade area, but the plan called for restoring native Douglas fir and open meadows to recreate the original natural environment. [63] If the Park Service purchased the Pearson Airpark property, which had become the top priority, an access to the reconstructed fort would be a long loop road from the Visitor Center to the south gate, and East 5th Street and McLoughlin Road would be restored to their original wagon trail dustiness.

For the first time, Fort Vancouver's planning document also outlined the concept of "living history." Not only would the stockade be reconstructed and surrounding farm land be restored, but "certain manufacturing activities such as blacksmithing, baking, and cask making [would] be revived as live demonstrations of the daily activities of the period, with the products made available for purchase." [64]

The immediate needs of the park, however, remained visitor facilities. A sheltered lunch area for school groups was planned near the Visitor Center and "a program of clean-up, grading, and planting is needed along the river front." As well, the local community could use the site for special purposes related to the fort's history, but only if they were "compatible with the primary purpose of preservation and maintenance of the historic scene." [65]

Master Plan of 1978

National Park Service Acting Director Harthon L. Bill approved the final Master Plan for Fort Vancouver National Historic Site on January 7, 1969, but by the early 1970s, the 1969 Master Plan again needed revision. The archaeological excavations, fort reconstruction, and interpretive program which emerged from the 1969 document helped generate interest and increased visitation at Fort Vancouver. City growth and regional planning as well as new environmental concerns presented new problems to the staff at Fort Vancouver. As early as March 1974, Fort Vancouver attempted to outline changes needed to the 1969 Master Plan. A Fort Vancouver Planning Directive ordered the park to systematically:

A. Develop alternatives for future development and interpretation based on increased input by local and regional planning agencies; historical societies, local elected officials, and interested citizens.

B. Consider alternative plans for circulation and automobile parking, public use pattern, and waterfront beautification.

C. Review factors necessary for an environmental assessment.[66]

By November 1975, a master plan preview committee recommended that the Columbia River waterfront be made into a greenbelt with only a few improvements such as parking, a pedestrian walkway, some interpretive markers, and the reconstruction of the historic Salmon House and Wharf. [67] Since the Pearson Airpark property was purchased by the Park Service in 1972, the new planning document had to reflect the phase-out of general aviation and the new interpretive program for the property. Finally, the committee agreed to a phase-out of a children's playground erected in 1970.

Published in February 1978, the new Master Plan included the primary goal of mitigating the impacts of Pearson Airpark. Though the Park Service owned the land and the airport was to be phased out within 30 years, Fort Vancouver still urged the City of Vancouver to remove hangars and other obstructions because in "their current location, these aircraft and hangars represent a major infringement on Fort Vancouver's historic setting. Relocation of these obstructions would make a major contribution to the visitors' appreciation and understanding of the historic setting." [68]

Reconstruction continued to be a priority. By 1978 the stockade, bastion, Chief Factor's House, kitchen, and washhouse had been completed. The master plan anticipated completion of the Indian Trade Shop, blacksmith shop, fur warehouses, and the Bachelors Quarters as the last parts of a 5-phase reconstruction program. The Park Service stressed authenticity of architectural structures based on archaeological and historical research and evidence. [69]

One mystery about the 1978 Master Plan remains unsolved. For some reason the Park Service dropped the parcel of land that lay southwest of the parade ground, which includes the Hudson's Bay Company cemetery from its ultimate boundary. Perhaps the Park Service felt that the Army would be too reluctant to give up the use of its facilities since many newer buildings had been constructed on that portion of Vancouver Barracks.

Planning for the Future and the Vancouver National Historic Reserve

A revised general management plan, as master plans were redesignated in 1979, for Fort Vancouver is overdue. Rapid change seems built into the basic agenda at the site, and since 1978, new circumstances have presented themselves. For instance, it is no longer certain that the entire Pearson Airpark property will revert to Park Service use after the year 2002 when the city's use of the property expires. By the mid-1980s a vocal community group which had city support, had formed for the purpose of forcing the Park Service to reverse the terms of the property sale made in 1972 and extend general aviation at Pearson indefinitely. In the face of the mounting pressures, the Pacific Northwest Regional Office created a task force to study possible use of the Pearson property after 2002. Headed by Deputy Regional Director William Briggle, the task force members, including Richard Winters, Stephanie Toothman, Wendy Brand, and Harlan Hobbs, visited Fort Vancouver in June 1987 to review the Pearson issue. [70] They concluded that "the park strongly supports proceeding with the concept outlined in the Master Plan of restoring a sense of the historic scene by planting the Pearson Airpark property in various field crops after the City's rights expire in 2002." Richard Winters, associate regional director of recreation resources and professional services, suggested that the Park Service develop a strong offense and begin planning for the property to demonstrate "our commitment to using this property in the manner for which it was intended--to enhance the visitor's understanding of this nationally and regionally significant historic site--and to avoid any further compromises that would cause us to deviate from that Congressional mandate." [71] In response to this suggestion, the Regional Office's Cultural Resource Division is conducting a Cultural Landscape Study which, based on archaeological, historical, and cultural landscape analyses, will update the Master Plan and help shape development and interpretation of Fort Vancouver.

Congressional Representative Jolene Unsoeld eventually joined the Pearson Airpark supporters to counter the Park Service's plan for utilization of the airport property and she introduced legislation to create a Vancouver National Historic Reserve. The Reserve Commission's recommendations regarding the suitability and feasibility of a larger, integrated, historical complex encompassing Vancouver Barracks will be forwarded to the secretaries of Interior and Defense in 1993. A series of cultural resource inventories prepared by consultants to the Commission evaluates the significant prehistoric and historic resources within the Reserve Study Area, including Vancouver Barracks, Pearson Airpark, Providence Academy and the Kaiser Shipyards. In addition, revised National Register documentation for the site, which indicates and evaluates the full range of historic resources within the site's boundaries, is being prepared for submission in 1993.

CONSTRUCTION, RECONSTRUCTION, AND DECONSTRUCTION

MISSION 66 Construction

Site Planning and Master Planning only laid the groundwork for the development of Fort Vancouver National Historic Site. The details of actual construction and the sequence of reconstruction can give us a more accurate picture of the changing cultural landscape.

Before 1961, Fort Vancouver National Monument included an open parade ground, an old Army fire station converted to a temporary office and museum, and a fort site which was denoted "by killing vegetation with a commercial plant killer" along the footprint of the stockade walls and old buildings. [72] The first significant construction began in August 1960, when ground-breaking for the MISSION 66 facilities took place on the parade ground for the utility corridors, roads, and parking areas of the proposed Visitor Center. [73] When these basic facilities were completed in November (including sidewalks), blacktop pavement was poured over the old foundations of the buildings within the stockade. The fort's well, the only visible surviving structure from the Hudson's Bay Company period, was then lined with field stones to ground level in order to accommodate visitors, and safety screens were installed. [75] Grass, which was kept watered and mowed, covered the rest of the fort site.

|

| The Fort Vancouver stockade well was the only visible surviving structure at ground level. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, it was lined with stone and managed as an interpretive site. (National Park Service) |

Construction of the Visitor Center, the utility buildings, and the two staff residences began in January 1961. Completed by early August 1961, the two residential buildings were single story with a living room, dining area, three bedrooms, hardwood floors, kitchen, utility room, one and a half baths, and attached garage. Superintendent Frank Hjort hoped that the new Visitor Center would provide enough space for interpretation of the site, an office for the small staff, and "a fire-proof vault for storage of artifacts." [76]

Unfortunately, a few defects remained. In September 1961, the Western Office of Design and Construction informed Superintendent Hjort that if "this contractor does not finish soon or at least make an effort we shall be compelled to hire a contractor to finish the job at his expense." [77] The contractor's work apparently created numerous "cracks in the concrete basement walls in the Visitor Center in the workshop, the restroom and the artifact storage room," which leaked badly. [78] It took several years of repair work to correct these problems.

Replanting the Orchard

Besides the visitor facilities, MISSION 66 provided for other improvements at Fort Vancouver. In 1962, an orchard was planted to represent the historic Hudson's Bay Company orchard. Though much of the orchard plan was created by guessing at its historic content, Fort Vancouver used a variety of historic and non-historic fruit trees, including: "Red Macintosh Dwarf Apple, Yellow Delicious Dwarf Apple, Stayman Winesap Apple, Bing Cherry, Black Tatarian Cherry, Montmorency Cherry, Elberta Peach, J.W. Hale Peach, Satsuma Plum, Peach Plum, Bartlett Pear, Jonathan Apple, and Boston Nectarine." The Park Service also planted various species on the grounds to control soil erosion including Myrtle, Oregon Grape, St. John's Wart, Salal, Rhododendron, Yew, Juniper, Kinnikinnik, Spruce, and Douglas fir. The planting of the orchard as well as general landscaping and decorative shrubs was completed in February 1962. [79]

Other landscaping and site beautification projects combined the efforts of Park Service planners and volunteers groups. Fort Vancouver maintained most of the parade ground and site north of 5th Street as meadow or lawn, with clumps of coniferous and deciduous trees, shrubs and flowering plants. In the spring of 1964, the Fort Vancouver Rose Society donated 52 `Tropicana' rose bushes for the Visitor Center as part of an effort to "beautify the public parks and buildings of Vancouver." [80]

Reconstructing the Stockade

The MISSION 66 building program did not necessarily anticipate reconstruction of the fort site. However, the modern facilities brought more visitors to the site and both members of the local community and Park Service staff at Fort Vancouver believed that the interpretive program could be further enhanced with more tangible reminders of the past. In March 1965, Representative Julia Butler Hansen supplied the means for building those reminders; she secured a budget of $100,000 to begin the reconstruction of the north wall and part of the east wall of the old stockade. Unfortunately, those funds were whittled down to $83,000 for the reconstruction project and the Moll Construction Company of Vancouver won the job with a bid of $73,800. [81]

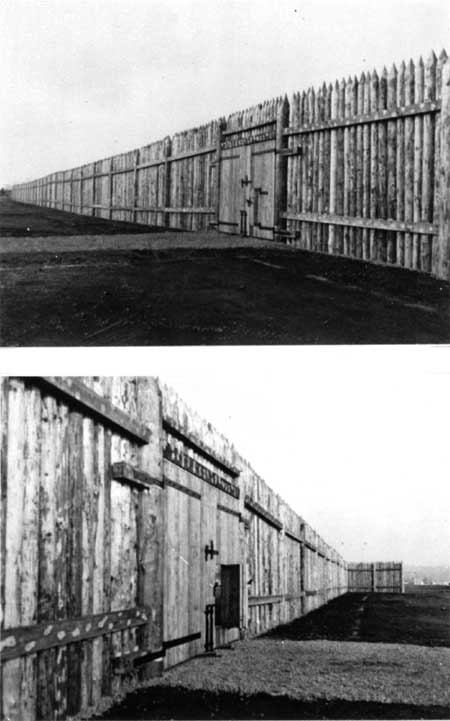

The design for the stockade was another challenge. The consulting architect in charge of the project, Lewis Koue, had to rely on many general or contradictory descriptions of Hudson's Bay Company forts and building construction. He also examined other reconstructed posts such as Fort Nisqually in Tacoma, Washington, and Fort Langley in British Columbia. By piecing together the historic sources and archaeological evidence, Koue was able to design the stockade and gate, but the plans for the 44-foot-high bastion were delayed. [82] Leland P. Hughey of the FAA Seattle Area office informed John W. Stratton, the acting regional director, that the bastion would exceed the height restrictions established by the Pearson avigation easement "by 13 feet and further aeronautical study is necessary to determine whether it would be a hazard to air navigation." [83]

Despite the bastion's delay, construction of the stockade began in July 1966, when "Jackhammers were brought in to break up the old Spruce Mill footings." [84] By November 29, a portion of the north wall log palisade had been completed. The work was done meticulously. To appear as accurate as possible, the palisade was constructed with

peeled, treated logs pointed on the top, set four (4) feet below ground level in concrete retaining walls, backfilled with fine gravel and sixteen (16) feet above ground level. There are King posts every twenty (20) feet into which are notched and pegged two six (6) by eight (8) inch walers on the inside. Each log is pegged through each waler top and bottom. All pegging is wood. [85]

At final cost of $85,608, the reconstructed fort palisade helped visitors to visualize the context of Fort Vancouver and spurred additional local interest in the site.

Though the bastion plan had been put on hold because of the Federal Aviation Administration's intervention, there was hope that the stockade would help convince the city to remove the avigation easement of Pearson Airpark's north runway, which by the mid-1960s was only used sporadically. [86] However, the avigation easement would not be completely lifted until 1972, when the Park Service bought the airport property from the city.

|

| Rebuilt in 1966, the north stockade wall copied the original design of peeled logs set deep into the ground and pegged. Unlike the original, however, these logs were treated to prevent decay. (National Park Service) |

The Children's Playground

National Park Service planning at Fort Vancouver affected the development of the site in a myriad of ways. For instance, in the late 1960s George Hartzog introduced a "Summer in the Parks" program for the National Capital Region, which provided programs to open the national parks up to urban children for recreation. [87] The Fort Vancouver National Historic Site 1969 Master Plan also encouraged "Related Visitor Services" which included "facilities for recreation purposes." The park wanted to provide facilities for groups, especially those with children, who visited "the park at mid-day to enjoy a continuous stay without the necessity of leaving the area for lunch; and to provide for children's play activities as a part of the park visit." [88]

Whether Fort Vancouver would have built a children's playground to fulfill the Master Plan objective on its own is unknown. But apocryphal stories concerning the playground's origins abound. The most plausible comes from Superintendent Eliot Davis. Sometime in 1969, according to Davis, "George Hartzog was on the grounds and agreed to [a permanent lunch shelter just south of Fifth Street.] At the same time he said `And let's have a playground and ball field, too.' The idea was that kids would have a place to play while they were at their lunch time." [89] Historian John Hussey recalls a rumor that George Hartzog "put his finger on the map--right out in the historic village site and orchard area--and said `put it here.'" [90] Of course, that location was out of the question.

Congresswoman Julia Butler Hansen also wanted the playfield; many believed that she had been walking through Fort Vancouver with George Hartzog and asked him where children would be able to play and he, in response, said "here." By November 1969, playground construction began, but on a site south of the Visitor Center adjacent to Fifth Street instead of near the stockade as originally planned. Eliot Davis was put on the spot to explain the playground to the regional office. In a memo to Urban & Environmental Specialist Steve E. Butterworth, he said it was "a long story." Davis had originally been against the idea,

but you don't buck George and Julia so this park went all out to do a good job. What do I think of a playground in a National Historic Site? I think it's great at this site but there are many where it would certainly not be acceptable. First there must be a need for it, second it must not be built to interfere with archaeology or historical interpretation and thirdly there must be room for parking and safe approach for children.

Though he felt pressured into it, Davis concluded that Fort Vancouver had such a great number of children visiting that the playground was necessary. Parents were happy about the additional park in town which was "away from town and freeway where there are no hippies, sailors or bums as in the park near the city center." [91]

Western Service Center designer Jim LaRock helped Davis configure the site and the playground was completed in June 1970. It embodied a "typical" western theme, including a frontier outpost, prairie schooner, and corral stockade. In addition, regular playground equipment such as a merry-go-round, slide, and swingset were installed, though the completion report recommended that the Park Service consider the safety and use of certain equipment if used in the future. For instance, the coil-spring toys were found to be relatively dangerous to children and the "western" equipment--the corral stockade and prairie schooner--were not even popular with the children. Finally, Superintendent Davis estimated that "every cat in Vancouver used the sandbox as a litterbox until it was removed." [92]

The playground issue, however, had not been resolved. Even though nearly 16,000 children used the area the first year it was installed, superintendents have been unhappy with its location, the decay and unsafeness of the equipment, and the inappropriate nature of a city playground at a national historic site. Playground equipment was removed sporadically over the years as it wore out, but in the spring of 1990, Superintendent Dave Herrera removed the remaining equipment south of the Visitor Center. There followed an immediate and intense reaction by the community. Mayor Bruce E. Hagensen "received several calls at City Hall objecting not only to the removal but also to the precipitous manner in which it was accomplished." [93] Regional Director Charles Odegaard's response was curt and to the point:

It is difficult to understand why anyone would consider the action precipitous when at least one piece of equipment per year has been removed for the past several years. Those pieces, like the present ones, were unsafe. At the same time, I am informed that there is playground equipment to the West at Esther Short Park, to the East at Marion Elementary School, and to the North at Waterworks. Should this equipment not be sufficient, might I suggest that the City consider placing equipment at the high school grounds which are within a quarter of a mile or so. [94]

But, apparently, other members of the Washington congressional delegation, Congresswoman Jolene Unsoeld and Senator Slade Gorton, received enough pressure from their constituents to demand that the Park Service bring back the playground. By April 1990, a more appropriate site was selected close to the picnic shelter which minimized impact on "the integrity of the historic site. The City of Vancouver has offered their assistance to acquire the equipment, install it, maintain it, and absolve the National Park Service of all liability." [95] Again, Fort Vancouver was forced to compromise on an issue about which it felt strongly.

|

| Controversial, but well-used, the Children's Playground, built in 1970, was moved to a more appropriate spot in 1990. (National Park Service) |

Reconstruction in the 1970s

The reconstruction of Fort Vancouver's north wall in 1966 had only been Phase I of a multi-phased reconstruction project. Robert Utley, Park Service chief historian, lamented that "without the other walls it looks rather forlorn and not altogether meaningful." There was no doubt that the historic scene of the Hudson's Bay Company post was "all but gone as a result of the intrusion of the municipal airport on the fort site and a highway and railroad that destroy its historic relationship with the Columbia River." [96] Indeed, further reconstruction was impossible as long as the airport existed. But the Park Service acquired the Pearson property in 1972 and the reconstruction plans moved forward. The bastion and the remaining portions of the stockade, completed in January 1974 at a total cost of $247,842, wrapped up Phase I of the reconstruction and Fort Vancouver moved quickly to start further site development. [97]

In 1974, the Park Service hired Lewis Koue (whom Merrill J. Mattes, the manager of the Historic Preservation Team at the Denver Service Center, called "the only qualified architect available") as project architect for Phase II construction. [98] Congresswoman Julia Butler Hansen, chairman of the House Interior Appropriations Subcommittee, found funds to both finish the archaeological excavations and begin construction of the structures within the stockade. Superintendent Donald Gillespie submitted two alternative proposals for funding the furnishing of reconstructed buildings as well as further planning and construction and exhibit production. [99]

The bakehouse was the next major structure to be reconstructed at Fort Vancouver. Russell Jones, the restoration architect, inspected the building in September 1974, and "found the brick piers for the bakery completed and the ovens laid up to a level just above the floor line." But, he thought that the masons may have been doing too good a job; the bakehouse looked too new which was "somewhat disturbing. The bricks are soft and I hope they will weather quickly. If they don't, before the end of the job they can be treated with a manure solution to give them an aged look." [100]

The details of reconstruction, such as the appearance of the brick, were important to both the project architects and the Fort Vancouver staff. Superintendent Donald Gillespie especially had an eye for detail and closely supervised the reconstruction of the fort. At one point he spent months tracking down hand hewn beams for the fort buildings. [101] There was still some doubt that hand hewn beams had been used in the original structures; certain construction questions could not always be answered from the archaeological excavations. In the end, primarily sawn beams were used instead, since the technology had certainly been available to the Hudson's Bay Company in the early 19th century, and for mid-20th century builders, they were easier to supply.

By June 1976, the Chief Factor's House, kitchen, and washhouse were completed in time for the National Park Service' American Revolution Bicentennial celebrations. The Chief Factor's House and kitchen were to be staffed by interpreters in period dress and the washhouse adapted as a comfort station and janitor's storage. [102]

|

| Chief Factor's House was the centerpiece of Phase II reconstruction. Completed in June 1976, the structure is still one of the most important interpretive sites at Fort Vancouver National Historic Site. (Oregon Historical Society, 1976) |

David Hansen, a Park Service furnishings specialist from the Division of Reference Services at Harper's Ferry and Julia Butler Hansen's son, joined the Fort Vancouver staff as curator in October 1974. One of his first tasks was to prepare a furnishings plan for the Phase II building interiors which were completed by the summer of 1976. [103] Despite the expertise available, occasional problems remained. For instance, the bakehouse ovens experienced "expansion and contraction, resulting in cracks," because they were only occasionally heated then allowed to cool. Historical Architect George Thorson concluded that the cracks were not critical, but even today, oven restoration work is once more necessary to prepare them for baking demonstrations. [104]

In 1976, the regional office and Denver Service Center (the successor to the Western Service Center) began planning Phase III of the Fort Vancouver reconstruction program. The most ambitious of the reconstruction projects, Phase III included the Indian Trade Shop, the blacksmith shop, iron store, and other trade shops. Estimated at a cost of $4 million, the regional office looked for ways to economize. In the fall of 1977, it considered cutting the Indian Trade Shop and blacksmith shop from the reconstruction package. "The new estimate should take into consideration new reconstruction techniques that can reduce costs," Acting Regional Director Edward J. Kurtz wrote:

An historic facade, rather than detailed reconstruction in kind, is what we have in mind. In the event that the current estimate of $2,431,000 construction net (including furnishings) for the structure cannot be reduced, I think it unlikely the proposed reconstruction will ever occur. [105]

The Fort Vancouver staff, led by Chief of Interpretation and Resource Management Sam Vaughn, urged that the Park Service keep the blacksmith shop and Indian Trade Shop as part of the project. A canvas tent had been used as a temporary trade store in the early 1970s and the staff did not want to return to this since the public would respond better to a more authentic structure. [106]

Reconstruction of the Phase III buildings did not begin until December 1980, with Lewis Koue and Murray Slama as the consulting architects. [107] Though the regional office had wanted to cut back on the number of reconstructed buildings, the blacksmith shop was completed by September 1981, and living history demonstrations began in 1982 with some 30 volunteer blacksmiths working an average of 5 days a week. A portion of the Indian Trade Shop, completed in 1981, was used in the late 1980s for the curatorial staff and the archaeological collection, the park's library, and offices for interpretive staff; the front contains furnished space that interprets all historic functions of the building. It took another 10 years to complete Phase III reconstruction which includes the recently completed fur store.

The Bandstand - 1980

The children's playground was not the only construction unrelated to the historical theme of Fort Vancouver which ended up on Park Service property. In early 1980, Sunset magazine asked the Vancouver Chamber of Commerce what it might do to commemorate the 175th anniversary of Lewis and Clark's arrival in the northwest. The Chamber of Commerce and the Fort Vancouver Historical Society were interested in holding a music festival "to attract attention and to raise money for the restoration of a bandstand on the old parade ground located south of Evergreen and between Fort Vancouver and East Reserve." [108] The managers of the City's Central Park Plan proposed the idea of reconstructing the historic bandstand that was once on the parade ground of Vancouver Barracks, in conjunction with the Lewis and Clark celebration. [109]

The regional director, Russell E. Dickenson, thought that the bandstand went against fundamental Park Service policy that reconstructions "intended primarily to serve as stages for demonstration or other activities, are not permitted." According to Dickenson, "The reason for the policy, is grounded in the Service's philosophy of maintaining integrity of both historic and natural resources. Single exceptions do little harm of themselves, but the effects, especially in a historic area, are cumulative." [110] This had been the case with the children's playground ten years earlier, now the regional office feared another structure would add to the problem. However, the Vancouver Central Park coordinator, Patricia Stryker, and the local bandstand committee found sufficient evidence of the location and original design of the historic bandstand to comply with Park Service policy. [111]

Local citizens donated money to the project and the bandstand was completed by the end of 1980. [112] In April 1981, the city and National Park Service signed a "Memorandum of Understanding" which clarified "the procedures and responsibilities related to use of the bandstand by the City and the National Park Service." Though donations covered the cost of construction, the Park Service agreed to maintain the grounds while the city was responsible for organizing and policing events that were held there. The original military bandstand had been a focal point for social gatherings of the civilian community and the U.S. Army activity in Vancouver from about 1871 to 1946. The modern replica would do the same and provide a place where local people could enjoy musical events. The historical criteria for its use included a ban on amplified instruments: "Appropriate events will feature music written or performed between 1853 and 1946. A performance may include music written after 1946 so long as it is compatible in style with that of the earlier period." [113]

The Fur Store

In 1981, Fort Vancouver completed the construction documents for the fur store, the second part of Phase III construction. But it was not until the mid-1980s that the plans got underway. In March 1985, Superintendent James M. Thomson notified the regional director that both the City of Vancouver and the Port of Vancouver were interested in entering a cooperative agreement with the Park Service to help build the fur store in order to use is as a repository for their artifacts as well. [114] The regional office was "concerned that we do not obligate the Service to perpetual care of collections that are not ours, without being assured of the annual funds necessary for their care and preservation," and so did not enter an agreement with the city. [115]

The price tag for the reconstruction was quite high, an estimated $1.5 to $2 million. Don Bonker, congressman for the Third District, suggested that the Park Service justify the price tag to the taxpayers. "To my mind," wrote Bonker in April 1987, "this is the most critical remaining construction aspect of the Fort's development. I would appreciate it if you could provide a more detailed break down of how the funds would be used as well as a description of your plans for the building's use." [116] The fur store was designed to function as a curatorial workspace and artifact storage facility, as well as archaeological study center. The interpretive portion of the building would depict the receiving, processing and preparation of furs for shipment from Fort Vancouver during the 1840s. [117]

By the late 1980s, the cost of the reconstruction had sky-rocketed to $2.75 million. "Completion of fur store is not a high regional, Servicewide or Departmental budget priority, but would be beneficial," declared a briefing statement for Manuel Lujan, secretary of the Interior. Representative Jolene Unsoeld supported the project after she was elected to Julia Butler Hansen's old House seat in 1988. But her support seemed contingent on the Park Service's acceptance of the Vancouver National Historic Reserve idea. [118] Unsoeld was able, however, to obtain $1.7 million for the 1991 fiscal year to continue the planning and design for the fur store.

The new fort building came with a different sort of price tag. As the thick file entitled "Fur Store Complaints" attests, not all members of the public shared Fort Vancouver's enthusiasm for commemorating the achievements of a fur trading culture. Several citizens protested the "symbolic tribute... to man's disregard for animal welfare." By glorifying the fur trade, they argued, the Park Service showed the same cruelty that trappers did in mutilating "innocent animals for fashion." They feared that the fur store would "teach our children that killing animals for nothing more than their skin is not only OK, but is an honorable thing to do." Others called the fur trade a "dark spot in our country's history." [119]

Fort Vancouver, however, stressed the need to accurately interpret history. "We believe that it is better that our history be understood than suppressed and will continue to interpret it in an accurate and sensitive manner," wrote Regional Director Charles Odegaard to one concerned woman. [120] Superintendent Dave Herrera assured the public that the reconstructed fur store would help the park "make the public aware of the needless slaughter of fur bearing animals for economic purposes and how this practice brought these animals to the brink of extinction." Herrera hoped that most people would "understand the fur trade within the historical perspective and not as an endorsement of the practice." [121]

Despite the public's concern, the reconstruction of the fur store moved forward. By early 1991, the original archaeological reports completed by Jake J. Hoffman and Lester H. Ross in the early 1970s had been reviewed by James Thomson, the regional archaeologist, and in June 1991, Bryn Thomas, of Eastern Washington University's Archaeological and Historical Services, began new excavations on the site of the building. The contract for reconstruction was awarded to the Lorentz Bruun Company of Portland and work began by the end of 1991. The massive timbers for the building, donated from the Gifford Pinchot National Forest, "will require a year to cure before they can be used for construction," Dave Herrera told the regional director:

Archaeological investigations and the installation of a utility corridor will be completed this summer. Additional funding will be needed next year to complete the interior of the building that will be used for archaeological storage and workspace and the interpretive area of the building. [122]

But, even as late as the summer of 1991, there was concern that the budget would not include the needed $1.7 million to complete the reconstruction project. The Park Service solicited assistance from Senator Slade Gorton to include completion funds for this project in the National Park Service budget. The Park Service and Congress decided that it would be most cost effective to finish the fur store; "To leave the building shell vacant and unused rather than pursuing its completion would result in additional maintenance expenses and deterioration with minimal return." [123]

As the fur store nears completion questions are raised about the future of continued reconstruction at Fort Vancouver. The amount of work completed belies any notion of removing the stockade, which was actually an alternative presented in 1981 by Lewis Koue and Murray Slama in Report Project A-1 Alternate Construction Systems and Alternatives to Total Reconstruction of Structures at Fort Vancouver National Historic Site. But, in economic hard times, funding will not necessarily be forthcoming for future reconstruction projects. Current superintendent Dave Herrera understands this constraint, yet maintains a vision of the full reconstruction of Fort Vancouver. Perhaps not today or even in 5 years, but maybe some day down the road.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

adhi/chap4.htm

Last Updated: 02-Feb-2000