|

FORT VANCOUVER

Master Plan |

|

THE RESOURCE

DESCRIPTION

Vegetation: Most of the park area is in grass which is maintained in meadow or lawn condition. The few clumps of oak and Douglas-fir that are scattered throughout the gently sloping grassy areas are all that remain of the original forest setting now largely taken over by exotic species of ornamental trees, flowering shrubs, and herbaceous plants.

A small fruit orchard, a re-creation of an historic feature, is adjacent to the fort site.

History: Fort Vancouver National Historic Site commemorates the enormous influence of the fur trade in the exploration, settlement, and development of the Pacific Slope and in the expansion of the national boundaries to include the present Pacific Northwest. It is classified principally under The Fur Trade, a sub-theme of the National Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings, Theme XV, Westward Expansion and the Extension of the National Boundaries to the Pacific 1830-1898. The agricultural phase of the fort's history was considered so important that the site is also classified under Theme XVIIA, Agriculture and the Farmer's Frontier.

The park also illustrates, as a minor theme, the part played by the United States Army in the opening of the West and in the development of the Nation into a world power. These lesser historical values are classified under Theme XIII, Political and Military Affairs, 1830-1860, and Theme XXI, Political and Military Affairs after 1865.

Fort Vancouver was the nucleus of the early development of the Pacific Northwest. For two decades, from 1825 to about 1846, this stockaded fur-trading post-headquarters and depot for the Hudson's Bay Company west of the Rocky Mountains was the economic, political, social, and cultural hub of an area now comprising British Columbia (Canada), Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and western Montana. It was the most important settlement from Mexican California on the south to Russian Alaska on the north.

The fur resources of the Pacific Northwest were discovered by British seamen who visited the northwest coast and obtained valuable pelts in trade with the Indians about the time of the American Revolution. Soon traders from the fledgling United States, Canada, and several European countries were competing on land and sea for the riches thus uncovered.

Stimulated by the reports of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, which had crossed the continent and descended the Columbia River to its mouth in 1804-1806, the New York merchant John Jacob Astor established a series of fur-trading posts in the Columbia basin beginning in 1811. Meanwhile, the North West Company of Montreal had opened posts in the present British Columbia and had expanded into the Columbia drainage area, taking over the Astor interests in 1813. The North West Company reigned supreme in the Pacific Northwest until 1821, when it was absorbed by the Hudson's Bay Company, a British firm whose operations then extended across the continent from Hudson's Bay to the Pacific Ocean.

In 1824 the Hudson's Bay Company decided to move its western headquarters from Fort George, at the mouth of the Columbia River, to a site about 100 miles upstream. This shift was made to strengthen British claims to the territory north of the Columbia River and to be on lands better suited for farming, since one objective of the firm's management was to make its posts as independent as possible of imported foodstuffs. The new post, constructed during the winter of 1824-1825, was named Fort Vancouver in honor of Captain George Vancouver, the British explorer. Five years later, in 1829, the fort was moved about one mile southwest to a more convenient location closer to the Columbia River. This second site, within the present City of Vancouver, Washington, is preserved by Fort Vancouver National Historic Site. The new post grew rapidly in size and importance.

|

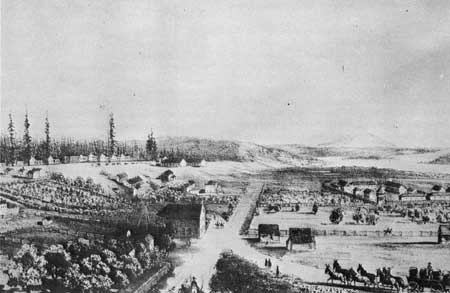

| Drawing of Fort Vancouver from the Railroad report. The village area to be excavated is in the right foreground. |

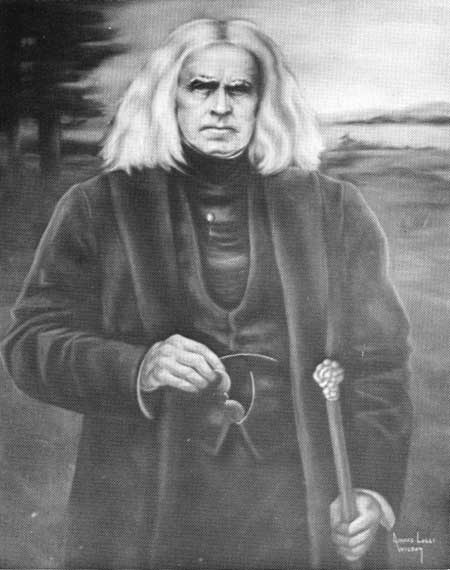

Fort Vancouver was the headquarters of Dr. John McLoughlin, Chief Factor of the Company's Columbia Department from 1824 to 1846. Of towering height and impressive appearance, he maintained a firm control over the Indians of his vast domain as well as over a small army of employees scattered from the Rockies to the Pacific and from Alaska to California. The Columbia Department maintained trading outposts on San Francisco Bay and in Honolulu.

Under McLoughlin's energetic leadership, the Hudson's Bay Company won a virtual monopoly of the fur trade in the Oregon Country. Although by international agreement this large area was open to trade and settlement by citizens of both the United States and Great Britain though under the government of neither, the British firm by vigorous trade methods eliminated most of its foreign rivals on land and along the coast. Thus for at least a decade, and longer in certain areas, the history of the Oregon Country and the Hudson's Bay Company activities centering about Fort Vancouver were almost identical.

Fort Vancouver was the nerve center of this vast commercial empire. Its warehouses received the annual shipments of trade goods and supplies from London and then distributed them to the many interior posts, to the fur brigades which ranged as far as present-day Utah and California, and to the vessels and forts which dominated the coastal trade far up the coast of Alaska. Each year the fur returns of the entire western trade were gathered at Fort Vancouver for shipment to England. The key to Vancouver's importance was its strategic position on the great Columbia River, which was navigable to this point by ocean-going vessels and which provided a route of water access to the interior.

The fort was also the center for an important farming and manufacturing community. The company's cultivated fields and pasturelands extended for miles along the north bank of the river. The crops produced by these fields, as well as by the fort's orchard and garden, demonstrated the agricultural possibilities of the Oregon Country and attracted the attention of potential independent farmers. Lumber, axes, flour, pickled salmon, barrels, boats, and other products of Fort Vancouver's mills, drying sheds, forges, and shops supplied not only the wants of the fur trade but also a brisk commerce with such distant places as the Hawaiian Islands, South America, California, and the Russian settlements in Alaska. These activities marked the beginning of large-scale agricultural and industrial development in the Pacific Northwest.

|

| Fort Vancouver stockade posts unearthed in 1948 excavation. |

In addition, much of the cultural and social life of the Oregon Country revolved about Fort Vancouver. Here were established the first school, the first theater, and several of the earliest churches in the Northwest.

Beginning in the early 1830's, as American missionaries and settlers started to flow into the Oregon Country in ever-increasing numbers, British-owned Fort Vancouver was of necessity their immediate goal. Here was the only reliable source of information about the country, here was the only source of emergency shelter and transportation, and here were the only adequate supplies of food, seed, and farm implements in the Northwest. Company policy, directed toward obtaining a Columbia River boundary between Canada and the United States west of the Rockies, did not favor encouragement and assistance of American immigration, but Dr. McLoughlin through humanity and necessity welcomed most settlers. His kind treatment of these pioneers helped foster the growth of an American population in the region. It was not until well into the 1840's that the independent farmers and settlers were sufficiently established to carry on without the economic assistance of the Hudson's Bay Company. Not without justice was McLoughlin later called the "Father of Oregon."

|

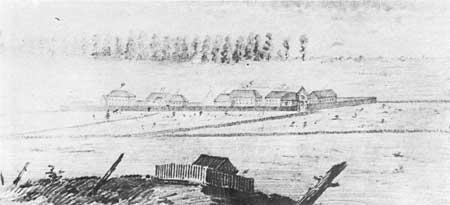

| Early sketch of Fort Vancouver by an unknown artist. (Provincial Archives, British Columbia) |

Due to the growth of this American population and because of the increasingly bitter dispute between Great Britain and the United States over the boundary question, the Hudson's Bay Company began to shift some of its depot activities from Fort Vancouver to Fort Victoria, in present British Columbia, as early 1843-1845. When the Treaty of 1846 established the boundary at the 49th parallel, Fort Vancouver found itself on United States soil, and the administrative shift to Victoria was accelerated. By 1849 the post had been reduced to a subordinate trading and supply center for the region south of the boundary, and in 1860 it was finally abandoned. A few years later a fire destroyed all remaining above-ground evidence of the old fur-trade emporium of the Northwest.

In 1849 the United States Army established its first Pacific Northwest military post on the hill immediately north of Fort Vancouver, and a short time later the old post was encompassed within a military reservation. Vancouver Barracks, as the new installation was known throughout most of its history, developed into the primary military center of the Pacific Northwest. In a day when rivers were the main transportation arteries, the same factors which had made Fort Vancouver such a strategic location for the fur trade attracted the attention of the Army.

As headquarters for the Columbia Department, Fort Vancouver was the command and supply center for the Pacific Northwest. From here troops were sent to engage in nearly all the Indian Wars of the region. During World War I the post was the site of a spruce lumber mill operated by the Third Spruce Production Division. After serving as a training and staging area during the second World War, the post was deactivated, and in 1946 most of the military reservation was declared surplus.

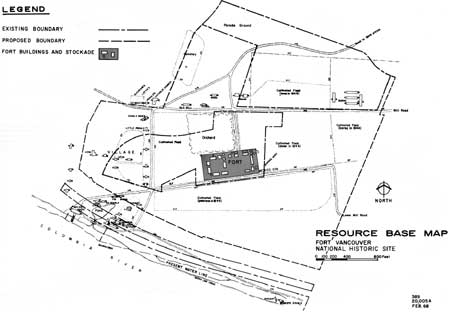

Appearance During Historic Period: At the height of its prosperity and extent—from about 1836 to 1846—the Hudson's Bay Company post at Fort Vancouver was an impressive establishment. The fort proper was situated on an extensive plain about a quarter of a mile north of the Columbia River. Enclosed by a 16-foot-high stockade, it measured about 732 feet by 325 feet, as large as five football fields laid side by side. After the spring of 1845 a bastion stood at the northwest corner of the stockade and mounted six or eight 3-pound cannon.

Within the stockade were 24 major buildings and several lesser structures, nearly all constructed of heavy squared timbers. Among the more important buildings were four large storehouses, an Indian trade shop, a granary, an impressive residence for the chief factor, dwellings for other company officers and clerks, a church, a powder magazine, and a jail. There were also offices, a blacksmith shop, and a bakery, while a cooper shop was located just outside the walls.

|

| The visitor center diorama depicting the arrival of the Whitman Party at Fort Vancouver |

The lesser employees at Fort Vancouver—the tradesmen, artisans, boatmen, and laborers—lived mainly in what was known as "the village," on the plain west and southwest of the stockade. This settlement consisted of from 30 to 50 wooden dwellings, some ranged along lanes and others dotted "all over the plain for a mile." Near the village and extending to the river was a lagoon, around which were a number of other Company buildings, with a wharf on the riverbank. The buildings included a large salmon storehouse, boatsheds, and a hospital. Between the lagoon and the village were barns and shelters for pigs, oxen, and horses.

Surrounding the fort and its outbuildings, the river-bank plain, about half a mile deep and several miles long, was a sea of cultivated fields and pastures. Across the plain and up the slope north of it ran several well-defined roads leading to the sawmills and grist mills up the river, to the wharf, and to several large forest openings or "plains" to the northward where the Company maintained additional farms. The fields were neatly fenced, and scattered about over them were barns, sheds, and other farm structures. Capping the sloping hill north of the fort was a dense coniferous forest.

Historic Physical Remains Today: After fire destroyed all visible vestiges of the fort during the 1860's, the exact location of the stockade gradually became forgotten. However, archeological excavations conducted by the National Park Service uncovered remains of the palisade posts and foundations of most of the buildings within the walls. The exact locations of all four stockade walls, the blockhouse, and the main structures have been marked out on the surface of the ground by asphalt topping. The only fort structure found intact during the excavations was the stone-lined well in the northeast corner. The top of the well has been restored, and the structure has been exposed for visitor observation.

During 1966 the National Park Service reconstructed the north stockade wall, the north gate, and about 32 feet of the east stockade. This work was as accurate a reproduction of the original as was possible on the basis of the historical information available.

The present park boundaries encompass only a small portion of the once-vast agricultural establishment that surrounded the fort. The larger part of the fort orchard site is on park lands, and to the extent that boundaries permit the orchard has been re-established. The varieties of fruit trees are those mentioned in historical accounts or those varieties known to have been available during the historic period.

Also within existing boundaries is the site of about half of "the village." Here, however, the exact locations of individual structures are known only from rather diagramatic historic maps and have not been determined exactly by archeological investigations.

Northeast of the fort site, on the hillside sloping up from the river plain, the existing boundaries include the sites of a row of cultivated Company fields and the locations of the main fort barns. Archeological excavations have confirmed the general location of the barns, but little was revealed as to the exact sites and sizes of the structures.

The present park also includes the Vancouver Barracks parade ground, thus preserving an important feature of the military post.

|

| Dr. John McLoughlin—a pastel in the visitor center. |

|

| This bible is thought to be the original Fort Vancouver bible of 1836. (Provincial Archives, British Columbia) |

Comparison of Scene During Historic Times and at Present: At the present time a visitor standing on the brow of the hill directly north of the Fort Vancouver site can observe a rather significant remnant of the scene familiar to Hudson's Bay Company employees. His eye travels downward across a sodded slope, over paved Fifth Street which occupies the location of an old fort road, past the partly-restored stockade and out over the grass runways and open fields of Pearson Airpark, then across the grassy embankment of the S.P.&S. Railroad, finally resting on a glimpse of the Columbia River and its tree-lined south shore. If the field of view is kept narrow and if a few modern intrusions, such as automobiles on State Highway 14, are overlooked, one can recapture in the mind's eye, if only fleetingly, the fort and its setting as revealed by early paintings and drawings. In particular, the important relationship between the fort and the river is clearly revealed.

On the other hand, if the eye strays only a short distance to the left or right, the scene is irrevocably shattered. To the east are the rows of parked aircraft and three lines of modern hangars of Pearson Airpark. These now extend nearly to the east end of the restored north stockade.

Beyond the airport on the riverbank rise the tall water tank and boxy outline of a new multi-story manufacturing plant. To the west the immediate foreground and the middle distance are occupied by a large number of substantial Vancouver Barracks structures, still being used by various Army reserve units. In the distance, beyond the old military reservation boundaries, rise the ironwork of the highway bridge across the Columbia and the interchange ramps of an elevated freeway, Interstate 5.

In summary, the historic scene at present is narrowly circumscribed and has been severely altered. What remains, beyond the small area within the present park, exists only because a large part of the airport is still open field and because the Army land contains a number of large trees which help to screen out buildings, the freeway, and the bridge. And even this remnant of the original scene is in imminent danger. If the uses of the airport and Army lands should change to industrial, the site of Fort Vancouver would be deprived of the setting which enables the visitor to understand the post's strategic location near the river and its importance as an agricultural establishment.

|

| Resource Base Map. (click on image for an enlargement in a new window) |

Archeology: No sites related to aboriginal culture have as yet been discovered within the park boundaries. Archeological excavations for evidence of the Hudson's Bay period were conducted by the National Park Service in 1947, 1948, 1950, 1952, 1961, and 1966. This work resulted in uncovering remains and determining the exact locations (and in most cases the dimensions) of the stockade and the major structures within it; and the general locations of the Company's barns have been confirmed.

A large number of artifacts from the Hudson's Bay period were recovered during these excavations. Such items as locks, hinges, nails, keys, and window glass throw much light upon the physical structure of the Company buildings. Other items, such as bottles, pieces of dinnerware, clay pipes, inkwells, trap parts, axe heads, and buttons illustrate the cultural, social, and industrial life at the fort.

The historical archeological excavations have been recorded by six reports, copies of which are on file at the park and in the Regional Office. Thousands of the excavated artifacts are stored at the park, where they are now being identified, classified, catalogued, and related to the field notes.

|

| Historic archeological excavation of the northeast corner of the Fort Vancouver stockade, showing the size of the pickets used. |

|

| Excavated bastion at Fort Vancouver. |

Recreation: The primary recreation resource of the park results from its open, natural character. This resource is well-recognized by Vancouver residents and organizations, who use it for the annual Fourth of July observances, in which large numbers of people participate; "rock-and-roll" jazz sessions; the originating point for civic parades; bicycling, horseback riding, and running.

While these uses have no relationship to the park's historical importance, they are either infrequent or are of little consequence, and have not detracted from the preservation and public enjoyment of the fort.

The second, more limited recreation resource is boating and related activities on the river frontage lands within the park. As pointed out in a previous section, the City of Vancouver has developed this resource to a minor extent.

The park also has a potential for forms of outdoor recreation use that would definitely contribute to visitor appreciation and enjoyment of the historic resources. These potential uses include picnicking and outdoor play, both as adjuncts to historical resource use.

|

| Typical activity during Fourth of July celebration at Fort Vancouver. |

EVALUATION

History—The primary resource which the park possesses is, of course, historical. Its national significance in illustrating an important segment of American history is recognized and established by reason of its inclusion in the National Park System.

As the center of all Hudson's Bay Company activities west of the Rocky Mountains, as the "cradle of civilization" in the Pacific Northwest, as the western terminus of the Oregon Trail, and finally as the location of the U.S. Army's Pacific Northwest headquarters, Fort Vancouver is the best site to illustrate and interpret such broad themes in American history as the fur trade, expansion of the national boundaries to the Pacific, the western military frontier, and agricultural developments in the Northwest corner of the country. The site was for more than 20 years the home and headquarters of Chief Factor John McLoughlin, the "Father of Oregon," who was nationally significant in the history of the United States. The site, still surrounded by an appreciable amount of open land as it was in historic times and still reasonably open to the Columbia River, possesses integrity.

The significance of the Fort Vancouver site has twice been considered by the Advisory Board and twice found to be of national importance.

Archeology—The archeological resource of the park is secondary in importance only to history. Actually, it may well be considered to be an integral part of the historical resource, for the knowledge necessary to accurately restore Fort Vancouver and its setting, and for correct interpretation, depends upon continued archeological research.

Recreation—As an area of desirable and useable open space in an urban community, the present park has major local recreational significance.

FACTORS AFFECTING RESOURCES AND USE

Legal Factors

Legal and Legislative History—Fort Vancouver National Historic Site is located on land which was part of the United States military reservation established around Fort Vancouver in October 1850. This reservation, reduced in conformity with a Congressional Act of 1853 to 640 acres, was subject only to the claims of the Hudson's Bay Company as guaranteed by the Treaty of 1846. These claims were extinguished by international negotiation in 1869. The reservation is thus considered as having been created from the public domain. Exclusive Federal jurisdiction over the land was recognized by Section 1, Art. 25 of the Constitution of the State of Washington and an act of the State Legislature approved February 24, 1891.

As early as 1915 the War Department designated the site of the Hudson's Bay Company fort as a "National Monument" under authority of the Antiquities Act, but evidently the recognition was soon withdrawn or allowed to lapse. During the 1920's and 1930's local citizens, historical societies, the City of Vancouver, and other agencies attempted to obtain Congressional authority and appropriations for restoring the fort stockade. Two laws (43 Stat. 1113 in 1925; and 52 Stat. 195 in 1938) authorizing reconstruction were actually passed, but no action resulted, seemingly because no funds were granted.

The opportunity for decisive action did not come until 1946, when a large part of the Vancouver Barracks Military Reservation was declared surplus to the needs of the Army. State and local historical organizations pressed vigorously for legislation to obtain a national monument or historical park to preserve the fort site. In 1946 officials of the National Park Service studied the area and reported that, to properly preserve the historical values, nearly all of the reservation between the Evergreen Highway and the Columbia River would be required for park purposes.

However, the City of Vancouver desired to make a local airport of the former Pearson Field on the reservation, and on March 14, 1947, by a quit-claim deed from the War Assets Administration it acquired a transfer in perpetuity of all of the reservation lands south of the Evergreen Highway not retained by the Army or held by the War Assets Administration for possible transfer to the National Park Service. A reversionary clause in the deed provides that ownership will revert to the Federal Government if the land ceases to be used for airport purposes; but subsequent legislation permits the city to sell all or part of the land if the proceeds are to be used for airport purposes.

The legislative drive to establish a national monument at Fort Vancouver was culminated by the Act of June 19, 1948 (62 Stat. 532), authorizing the establishment of Fort Vancouver National Monument with a total area as established or as enlarged not to exceed 90 acres. Enlargement within the 90 acres was restricted to lands acquired through surplus Federal property procedures or through donation.

Prior to the enactment of this bill the National Park Service agreed that the City of Vancouver could have an avigation easement over the old fort site proper. This agreement was a necessary pre-requisite to the release of the site by the War Assets Administration.

Pursuant to the Act and this agreement, the WAA transferred administration of 53,453 acres of the old military reservation to the Department of the Interior by a letter dated May 19, 1949. This land was in two sections: Parcel 1, 8.156 acres, situated south of Fifth Street and containing most of the site of the Fort Vancouver stockade; and Parcel 3, 45.297 acres, situated between Fifth Street and East Evergreen Boulevard and containing the greater part of the Vancouver Barracks parade ground.

In accepting this transfer on May 24, 1949, the Department of the Interior agreed to the terms of the avigation easement in favor of the City of Vancouver. This easement gave the City the right of free and unobstructed passage of aircraft over the entire 8.156 acres of Parcel 1. In addition, the Service was prohibited from placing any buildings or other structures above ground level, and visitors were specifically forbidden to enter that portion of the monument.

During the Korean War a portion of Parcel 3 containing 2.75 acres of land and several barracks buildings was taken back by the Army, and in 1951 the National Park Service agreed to let the Army use Tract "G" at the western end of the parade ground for organized reserve corps purposes under terms of a revocable use permit. The 2.75 acres have never been returned to the national monument. Thus the combined areas of Parcels 1 and 3 was 50.703 acres.

This arrangement was formalized by a Park Service-Army agreement reached in December 1953, and by a Service letter of April 15, 1954, which permitted the Army continued occupancy and use of Tract "G." However, the Service can terminate the use permit at any time, and hence it constitutes no barrier to park development and use.

As a part of this arrangement, the Department of the Army by a self-executing letter dated December 16, 1953, transferred to the National Park Service a tract of 9.21 acres known as Parcel 2. This land was south of Fifth Street and contained the remainder of the stockade site. The total land under National Park Service administration after this acquisition was 59.917 acres, as then measured.

The principal sites which the park was designed to protect—the fort location and the parade ground—having been acquired, the Secretary of the Interior, by a Departmental Order of June 30, 1954, officially established Fort Vancouver National Monument.

Several years later the General Services Administration desired to dispose of the very narrow riverfront section of the former military reservation lying between the City of Vancouver's Kaiser Access Road (Columbia Way) and the Columbia River. The City of Vancouver wished to obtain this property, but it could not give assurance that structures would not be built on it which would interfere with the historic scene as viewed from the fort site and the monument visitor center. Therefore the Service exercised its prior rights, as a Federal agency, to the surplus property and acquired this river tract of about 6.5 acres by transfer from GSA on December 4, 1957 (accepted by the Department, January 15, 1958). The National Park Service, in turn, issued a permit to the City for use of the property as a public park and boat launching ramp. As extended, this waterfront use permit will continue until 1973.

Along with the river tract, the General Services Administration asked the Service to take over administration of the 100-foot-wide Spokane, Portland and Seattle Railway right-of-way which runs across the old military reservation directly north of the Kaiser Access Road. It was felt that as the Federal agency controlling the nearest land to this government-owned strip, the National Park Service was the logical organization to retain custody. The Service saw the desirability of maintaining control over this strategic parcel in order to protect as much as possible the historic scene and to prevent future disposal to an owner unsympathetic to the scenic requirements of a historical park. Also, taking the very long view, it was realized that it would be desirable to acquire the land should S.P.&S. Railway ever relinquish its rights to use the easement over the parcel. Thus the Service accepted the Railroad Tract of about 8.3 acres on January 15, 1958. These two acquisitions brought the total acreage of the monument to 74.623 acres, as then measured.

From the very first planning at Fort Vancouver, the Service had realized that more land would be necessary to protect the fort setting than the 90 acres to which the monument was limited by the authorizing legislation. In 1954 the Service made definite recommendations for proposed ultimate boundaries, and on January 26, 1955, Secretary McKay approved this proposal "as a general planning objective." Shortly thereafter the Service suggested new legislation to authorize an enlargement to permit eventual accomplishment of these boundary recommendations.

This move was successful, and on June 30, 1961, the President approved an Act of Congress (75 Stat, 196) which permitted the Secretary to revise the boundaries to include not more than 130 "additional acres." Thus a total land area of 220 acres is authorized. The Act also authorized the Secretary to acquire "in such manner as he may consider to be in the public interest" the non-Federal lands within the revised boundaries. This clause removed the earlier prohibition on the purchase of lands. The new law also permitted heads of executive departments involved to transfer surplus lands needed for the park directly to the Secretary of the Interior. It also changed the name of the area to Fort Vancouver National Historic Site.

With the easing of the area limitations, the Service was able to acquire from the Department of the Army by a self-executing letter of May 14, 1963, a parcel of 14.5 acres lying west and southwest of the Hudson's Bay Company fort site. This area includes about half of the site of "the village" which was associated with the old fort. This tract was subject to several easements, largely for water lines. The only one which seriously restricts Service use of the land is an Army Aircraft Taxiway easement giving unobstructed access over a designated one-acre route from Army property on the north across the tract to Pearson Airpark on the southeast. With the acquisition of this parcel, the total area of Fort Vancouver National Historic Site was—and still is—89.123 acres.

|

| Fort Vancouver—built in 1824. (Provincial Archives, British Columbia) |

The existence of the avigation easement over all of the Hudson's Bay fort site (Parcel 1) so hampered interpretation of this important historical resource that the National Park Service has attempted for some years to obtain modification. An opportunity came in about 1961 when it was discovered that the June 1959 edition of the FAA regulations for small airports defined avigation easements at the ends of runways in such a manner as would free at least part of the site from the very restrictive provisions hitherto existing. On February 27, 1962, the City of Vancouver and the Secretary of the Interior signed an agreement reducing the easement to the limits of the 1959 regulations.

As a result of this accord the Service was able to rebuild the north and part of the east walls of the old fort stockade in 1966. Also, by fencing the limits of the avigation easement, visitors can be permitted on the north portion of the fort site.

On October 21, 1966, the Western Regional Office submitted a boundary status report recommending that 122.43 acres, in seven separate tracts, be acquired for addition to Fort Vancouver National Historic Site. All available data on boundary descriptions and tract areas have been obtained and submitted to the Washington Office.

Summary of Legal Factors Relating to Planning Limitations on Land Use—Avigation easement to City of Vancouver prohibits reconstruction of additional stockade sections or of structures within or adjoining the stockade; also prohibits visitor access to most of fort site.

Army aircraft taxiway easement on part of old "village" site restricts erection of structures, fences, signs, and other developments in that part of area.

S.P.&S. Railroad use permit, extended and confirmed by Secretary of the Interior on December 4, 1954, prevents removal of railroad embankment and opening view from fort site to the Columbia River.

The Clark County P.U.D. has an easement to bring utilities to the visitor center, residences, and utility area until 1977.

Limitations on Land Acquisition—The Act of June 30, 1961, limits the total area of the national historic site to 220 acres.

Other Commitments—A use permit to the City of Vancouver gives the City use of the waterfront strip for park and recreation purposes until 1973.

A Service commitment permits the Portland Area Boy Scouts to anchor a barge and boats off the riverfront section if they elect to do so.

|

| Interior of Fort Vancouver, looking northwest, showing the tents of the British Boundary Commission—1860. (Provincial Archives, British Columbia) |

Type of Jurisdiction—The Federal Government has exclusive legislative jurisdiction over all lands within present boundaries.

Climate and Topography

The climate is influenced by Pacific Ocean currents and is quite mild and wet. Temperatures of zero to minus five degrees have occurred, but are exceedingly rare. There are very few days with temperatures over 100 degrees. Typical summer weather is between 70 and 80 degrees, with usual winter temperatures from about 40 to 55. The area receives some snowfall in December and January, but there have been years with little or none whatever.

Prevailing winds during the summer are from the northwest, averaging 8 to 9 miles per hour. Prevailing winter winds are from the southeast, with an average velocity of about eight miles per hour. However, high winds do occur, and at least one heavy fall blow from the southwest can usually be expected, which will vary from 60 to as much as 120 miles per hour.

There are long periods of wet weather. Statistics for the 30-year period 1929 through 1958 show that the mean number of days with precipitation of over one tenth inch was 97, requiring the use of shelters for outdoor facilities. In contrast, the months of July and August are so dry that irrigation is required to maintain lawns and gardens.

The climate, however, does not materially influence total park visitation or its pattern of use. Most visitation is during the spring and fall, while visits by students during the school year are largely independent of weather conditions.

The topography of the park is formed by the flood plain of the Columbia River. The area slopes gently from the north to the river, with elevations from 102 feet m.s.l. at the north to 24 feet m.s.l. at the river.

The site of Fort Vancouver lies on the first narrow flood plain of the Columbia. The terrain quickly begins a short rise to the second, or Mill Plain. From the rising ground above, the visitor can view the entire scene, including the far side of the Columbia River.

The history of seismicity in Oregon shows that the Portland-Vancouver area receives an earthquake of the magnitude of 5 on the Richter scale on the average of once each five years. Any tall masonry structures, such as chimneys, therefore need to be constructed with this in mind.

Soils

The flood plain and the rising ground behind it consist of a fairly uniform gravelly loam 12 inches or more in depth over alluvial gravel. Surface runoff is quickly absorbed, making irrigation necessary for the maintenance of healthy vegetation.

|

| A ranger with a group of school children around the old well on the site of old Fort Vancouver. |

VISITOR USE

Most visitation is on weekends during the spring and fall months. About 80 percent of visitors are family groups. School groups, consisting of students in the fourth grade and up, from within a 50-mile radius of Vancouver, compose about 10 percent of the visitors. These groups range in size from approximately 30 to 150 students who visit the park during the school year as a part of the school curriculum.

The present pattern of visitor use is quite simple. The focal point for the park visit is the interpretive exhibit in the visitor center. Slide shows are available to the public on weekends, but guided tours are offered to the general visitor at any time. Comparatively few people visit the fort site. At present, the interest there is not sufficient to attract the average visitor.

School groups are given a conducted tour through the public portion of the visitor center. The tour includes a slide show. The average length of stay for school groups is 45 minutes unless they visit the fort site, in which case it is about 1-1/2 hours.

The groups arrive between 9:00 A.M. and 2:30 P.M. Those that have scheduled their visit to include the lunch hour need lunch facilities. They are encouraged to use the city parks for this purpose. There is no existing or proposed sheltered outdoor picnic area within the immediate vicinity, however, and during inclement weather the groups are permitted to lunch in the visitor center lobby or at the sheltered entrance. Of the 283 school groups who visited the park in 1967, 25 groups lunched in the area. A considerably greater number, perhaps a majority, also would have done so had sheltered picnic area space been available. This facility should accommodate up to 150 children.

At the present time, the length of stay necessary for the casual visitor to absorb the park story does not require lunching to ensure an uninterrupted visit. If the major fort structures were restored, however, he would almost certainly spend the greater part of the day in the park. In that event, the availability of lunch facilities would greatly enhance his park experience.

The annual Fourth of July observances, staged by local service clubs, attract crowds of up to 20,000. Activities conducted as a part of these annual observances are:

Band concerts, including "rock and roll" bands

Cannon firing

Speakers

Fireworks displays

Water fights by the Vancouver Fire Department

Food concessions (set up on East Fifth Street)

Parades for "Miss Washington" contest, which are made up on the parade grounds

The park also receives incidental recreation use, both passive and active, by neighborhood residents including walking, sunbathing, practice golfing, horseback riding, and cross country running.

Still other incidental uses include National Guard and Reserve Corps parades and artillery problems; Bureau of Public Roads field survey crew training; and art classes.

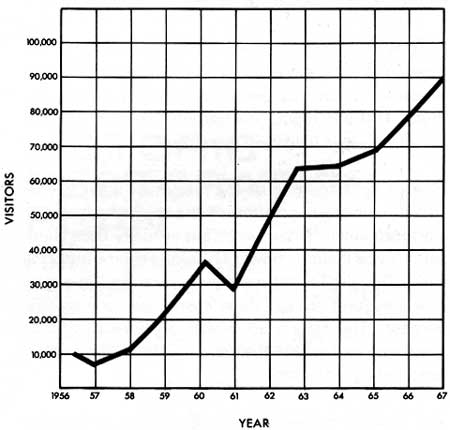

According to present forecasts, park visitation is expected to reach 123,000 by 1970. This forecast is based on present development only; with major restoration, a significant increase in visitation could be expected.

The estimated carrying capacity of the park with full development and restoration would be about 1,000 persons at any one time, exclusive of special events.

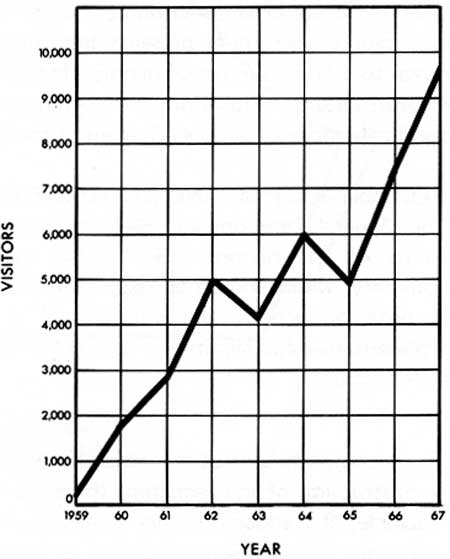

YEARLY SCHOOL GROUP VISITATION

(ROUNDED TO THE NEAREST THOUSAND)

SOURCE: MONTHLY PUBLIC USE REPORTS

YEARLY VISITATION FIGURES 1956-1957

(ROUNDED TO THE NEAREST THOUSAND)

SOURCE: MONTHLY PUBLIC USE REPORTS

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

master_plan/sec2.htm

Last Updated: 07-May-2007