|

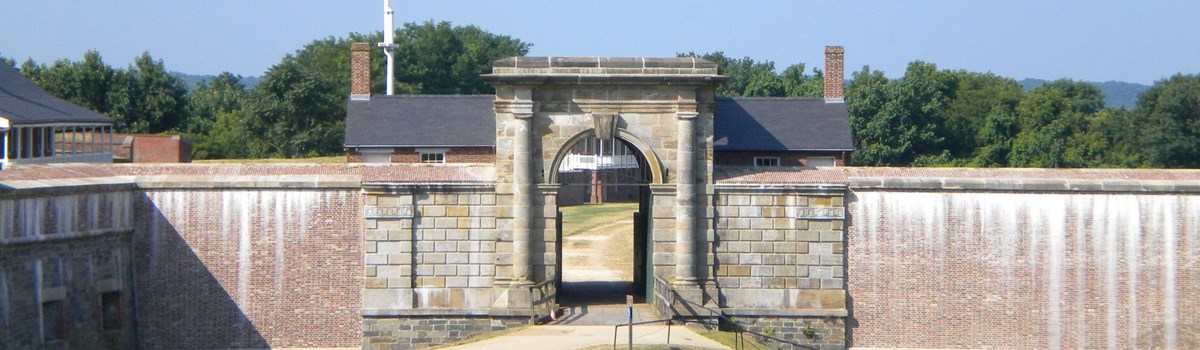

Fort Washington Park Maryland |

|

NPS photo | |

Fortification for a Capital

Fort Washington is the story of changing military strategy, of changing technology, and of a rapidly growing and maturing nation. It is the accumulation of events and ideas and the physical remains of several forts rather than of one climactic act or of one structure. It thereby illustrates a significant portion—from 1808 to 1922—of American history and the continuing debate about how best to defend the United States. The first fort on this location was one element in a system, based on 18th-century French ideas of military architecture and strategy, to protect the eastern seacoast. The British attack on and subsequent burning of Washington powerfully showed that a new defensive plan was needed. In the wake of the War of 1812, the Fort Washington that we know today began to take form. It was designed and constructed under the supervision of Lt. Col. Walker K. Armistead, the brother of Maj. George Armistead who distinguished himself in the defense of Fort McHenry, Md., on September 23, 1814. Like its predecessor, this fort was to be part of a system that would defend the East Coast, not just Washington, from naval attack. During the Civil War the development of armored ships and rifled cannon altered the nature of warfare. Armored ships could approach closer than wooden ships had been able to and could use rifled cannon to demolish brick fortifications. The answer was concrete batteries that housed larger rifled cannon with a greater range. Even though the batteries were located away from the river, they were as effective as the earlier brick structure had been against wooden ships. Fort Washington is not just one structure but several that were built to meet the changing demands of strategy and technology. And it is one of only a handful of U.S. seacoast fortifications still in their original form.

What's Going On

The life of a Civil War-era soldier is portrayed through Fort Washington's many living history programs. Park interpreters and volunteers, dressed in authentic U.S. Army uniforms, recreate the life of a 19th-century military garrison. They load and fire muzzle-loading weapons and cannon, talk about the everyday life of enlisted men and officers in their respective quarters on the parade grounds, and conduct the ceremonies of military life. They also discuss the difference between smoothbore and rifled artillery and explain the significance that rifled artillery had for Fort Washington. These living history programs take place only at specific times.

Picnicking and hiking are popular activities in the park, and you may fish along the Potomac River. Call the park about reserving picnic areas in advance.

From Fort to Park

In 1872 the U.S. Army turned over control of Fort Washington to the Army engineers, who then constructed new gun positions. In 1896 work on eight concrete batteries began near the old fort. They were outfitted with Endicott-era guns: 10-inch rifles on disappearing carriages, 12-inch mortar batteries, and four-inch rifles. Land was purchased and similar installations were built directly across the Potomac.

In 1921, after the post was no longer needed, it became the headquarters of the 12th infantry. During World War II the Adjutant General's Officer Candidate School was based here. In 1946 the fort was deactivated and became part of the National Park System so that the historic fabric of the fort itself could be preserved and recreational facilities could be provided.

Fort Washington History

1808-1814

The Treaty of Paris, which ended the American Revolution and created the United States, did not settle all problems between Great Britain and her former colony. Slowly, tensions mounted again, and as they did, belief in the inevitability of war grew. To protect the national capital, the United States began work on Fort Warburton in 1808, and by December 1, 1809, it was finished. Sited on the Maryland shore of the Potomac River across and upriver from Mount Vernon, as suggested in the 1790s by George Washington, the fort commanded the Potomac. Perpendicular earthen walls stood 14 feet above the bottom of the ditch that surrounded the river side of the fort. A tower facing the river contained six cannon. Fort Warburton stood only five years. On August 19, 1814, British forces landed at Benedict, Mo., on the Patuxent River and marched overland to Washington, D.C. On August 24 they routed an American force at Bladensburg and entered the defenseless city, burning the Capitol, the White House, and most other government buildings. The next day British warships sailed up the Potomac headed for Alexandria. In the face of certain destruction of the fort, Capt. Samuel Dyson chose to evacuate his men and used the powder to blow up the fort so that it could not fall into British hands.

Within less than a month of its demolition, Fort Warburton began to rise from its own ashes. The project was directed by James Monroe, acting secretary of war, who hired Pierre Charles L'Enfant, the French engineer who had drawn up the plans for Washington, D.C. As work continued, however, the threat diminished. Concern about the defenses of Washington had lessened considerably by the time news arrived that a peace treaty had been signed in Ghent, Belgium, on December 24, 1814, and that American troops had handily defeated the British at the Battle of New Orleans, January 8, 1815.

1815-1860

Even before the Treaty of Ghent, Monroe had begun to rein in L'Enfant. In November 1814 he questioned L'Enfant's removal of some of the old fort and asked for greater economy. L'Enfant was told to submit reports on the work in progress and to prepare detailed plans of the new fort for the War Department. Believing he had been insulted, L'Enfant refused to comply. On July 18, 1815, work was halted and two months later, on September 15, L'Enfant was dismissed. He was replaced by Lt. Col. Walker Armistead of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, who, within a few weeks, presented the first detailed plans of the proposed work. Construction of the new brick fort progressed steadily under the direction of Armistead's assistant, Capt. T. W. Maurice. On October 2, 1824, the fort was declared finished, though as yet unarmed. It had cost $426,000.

In the 1840s the fort underwent an extensive remodeling program. Work crews constructed 88 permanent gun platforms, increased the height of the east wall, rebuilt the drawbridge, strengthened the powder magazines, and added a caponniere to protect the approaches from Piscataway Creek.

1861-1865

Growing shortages in the number of personnel after the Mexican War stretched the resources of the U.S. Army. At Fort Washington, as at many other posts, the garrison was withdrawn leaving only a skeleton maintenance staff. As sectional differences increased and the country moved closer to the horror of civil war, Fort Washington found itself in a precarious position; near the Nation's Capital and across the river from the most populous slave state.

By February 1861, after South Carolina and six other states had declared their independence from the United States, the possibility loomed that Virginia would also secede, making the fort's geographic position critical. Other observers saw a threat from the southern sympathizers residing in Prince Georges County, Md., where the fort was located.

On January 1, 1861, Secretary of the Navy Isaac Toucey issued an order for the defense of the capital. The task of putting the defenses in order fell to an Army engineer officer, Lt. George Washington Custis Lee, son of Col. Robert E. Lee. By early May 1861 both Lees would resign their commissions in the U.S. Army and offer their services to their home state, Virginia.

Forty Marines under command of Capt. Algernon S. Taylor were assigned to Fort Washington, at that time the only fortification near the city. Taylor feared that the 40 Marines were not enough and asked for reinforcements. On January 26, 1861, a company of U.S. Army recruits relieved the Marines. On April 15, the day after Fort Sumter surrendered in Charleston harbor, the War Department sent the 1st U.S. Artillery to Fort Washington. It was commanded by Capt. Joseph A. Haskin, who had arrived in Washington from Baton Rouge, La., where he had been forced to surrender the federal arsenal and barracks to local secessionists earlier in the year.

For a time Fort Washington was the only defense for the national capital, and it was vitally important, for it controlled movement on the river. Quickly, however, Maj. Gen. John G. Barnard of the Corps of Engineers directed the building of a string of 68 enclosed earthen forts and batteries to protect all approaches to Washington. By the end of the war, 20 miles of rifle pits and more than 30 miles of military roads encircled the city. Remnants of some of these defenses can still be seen today.

1872-1889

At the end of the Civil War, federal officials took a close look at the coastal defense system. They found that U.S. coastal waters were vulnerable to ships carrying 12-inch guns and of less than 24-foot draft. In short, the U.S. coastline was vulnerable to the world's major naval powers—Great Britain, France, Russia, Germany, Denmark, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Austria-Hungary.

In 1872 the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began to prepare new defenses. Between 1873 and 1875, four 15-inch Rodman guns and a magazine were partially constructed. Work ceased in 1875 when money was no longer available. In the mid-1880s the U.S. Army's Endicott Board designed a new coastal defense system that called for concrete structures and rifled guns that could penetrate the armor plate of enemy ships. Fort Washington was strengthened with mortars that could penetrate the thinner decks of ships. Plans were also prepared for laying minefields in the Potomac.

1890-1898

The year 1890 ended with a surplus in the federal budget, and it was decided to use some of the money for coastal defense.

Between April 1891 and September 1902 fortifications guarding the river approaches were built and existing ones strengthened. Gun batteries were erected at Fort Hunt across the river in Virginia. Fort Washington became the headquarters for these installations. Work continued the next year with the building of the mine casemate and Battery B, later renamed Decatur.

In 1896 the two gun magazines and the gun mounts in the ravelin of the old fort and two magazines were completed. On July 12, 1897, Fort Washington was garrisoned by Company A, 4th U.S. Artillery, the first permanent garrison since 1872.

In April 1898 the U.S.S. Maine exploded in Havana harbor and the United States became engaged in the Spanish-American War. Up to this time work on the entire coastal defense system had been slow and only a few of the gun batteries were completed. Work began immediately so that any possible attack by Spanish warships could be met. Two of the 15-inch Rodman cannon in the ravelin were dismounted and a concrete battery was built for rapid-fire guns. Electricity and telephones were installed in the batteries, and the 10-inch gun planned for firing at the experimental battery was placed on a barbette carriage near Battery Humphreys. A minefield was also laid down in the Potomac, the only time this has ever been done. Finally, four National Guard companies of the 15th Pennsylvania Infantry Regiment were stationed at Fort Washington.

1898-1940

On July 3, 1898, the U.S. Navy destroyed the Spanish fleet at Santiago, Cuba, and for all practical purposes the Spanish-American War was over. The mines were removed from the Potomac River, and later that year the 10-inch gun mounted near Battery Humphreys was moved to a new mount to test a wood and iron parapet that had been built shortly before the outbreak of war. In June 1899, what became known as the Algiers test was conducted by firing one of these guns into a parapet designed by the secretary of war. The results of the test concluded that concrete provided a more effective barrier against rifled artillery than any other design then available to engineers.

In July 1899 Batteries Decatur, Emory, Humphreys, and White were officially turned over to the artillery commander of the fort. Although in the hands of the artillery since their construction, they had been the property of the engineers.

During World War I, the two guns of Battery Decatur were removed and shipped to Fort Monroe, Va., where they were shipped to Europe for use in France. Fort Washington was garrisoned by the District of Columbia Coast Artillery, and a number uf military units were organized at the post. Fort Washington was also used as a staging area for troops going overseas.

From June 1922 to June 1939, the 3rd Battalion 12th Infantry occupied Fort Washington. The fort's primary function was as a city garrison for Washington. Its soldiers participated in a variety of state occasions—parades, ceremonies, and funerals—throughout these years. In 1939 the 3rd Battalion moved to Fort Myer near Arlington Cemetery. That same year the fort was transferred to the Department of the Interior and a Civilian Conservation Corps barracks was built.

1941-Present

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941, the nation quickly turned from peacetime activities to meeting the demands of wartime. Already existing facilities were pressed into service, and Fort Washington was returned to the Department of War for use during World War II. During this period further expansion of the post took place with the construction of additional buildings to house students and to provide support services for training military personnel.

The Adjutant General School moved to Fort Washington in January 1942. It trained Army officers in administration and personnel classification duties. The school turned out 300 trained officers every 60 days. Part of the Adjutant General's School was an Officer Candidate School that graduated 25 men in the first class and thereafter turned out 20 new officers every three months.

Toward the end of the war, the Veterans Administration used part of the area and other buildings as public housing. In 1946 the fort once again reverted to the Department of the Interior. Many of the buildings from the interwar period were removed. Since that time it has been a public park commemorating the long history of coastal fortifications and serving as a recreational area for history buffs, naturalists, and other park visitors.

Getting Here

(click for larger map) |

Fort Washington lies on the Maryland shore of the Potomac River, south of Washington, D.C. From the Capital Beltway (I-95/495) follow the signs for Indian Head Highway (Md. 210 ). Take Exit 3A and go south on Indian Head Highway. Turn right onto Fort Washington Road to the park. There is no public transportation to the park.

The visitor center, located in the yellow house on the hill in front of the fort, contains exhibits describing the history of Fort Washington as the guardian of the Nation's Capital. An audiovisual program also explores the park's history. A sales counter offers materials on Fort Washington and the National Capital area. The parking lot, visitor center, restrooms, picnic areas, and parts of the fort are wheelchair-accessible. The park is open every day; the fort and visitor center are open daily except January 1, Thanksgiving, and December 25. An entrance fee is charged.

Approximately four miles upriver from Fort Washington lies Fort Foote, constructed during the Civil War as one of the circle forts protecting Washington, D.C. This fort, with its large 15-inch Rodman cannons, replaced Fort Washington as the major defense on the Potomac River. It remained an active post until 1878 when the defense of the Potomac River was returned to Fort Washington.

Safety

Fort Washington is a 19th-century fortification with some inherent dangers. In maintaining the authenticity of the fort some of these dangers remain. Please observe the following:

• Stay off the parapet and watch your children.

• Do not climb on any part of the fort, or on the batteries built during the late 19th and early 20th centuries; some may be unstable.

• Make sure that pets are on a leash and under control at all times.

• Leave plants and native wildflowers for others to enjoy as much as you do.

• Be on the watch for poison ivy. Remember the rhyme "Leaflets three, let them be."

• Report any accidents to a park ranger or to the U.S. Park Police as soon as you can.

Source: NPS Brochure (2003)

|

Establishment

Fort Washington Park — 1946 (Department of Interior) |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

An Annotated List of the Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) Found in Fort Washington and Piscataway National Parks, Maryland (Theodore W. Suman, 2004)

An Annotated List of the Spiders (Arachnida:Araneida) Found in Fort Washington and Piscataway National Parks, Maryland (Theodore W. Suman, 2004)

Foundation Document Overview, Fort Washington Park, Maryland (December 2016)

Historic Fort Washington on the Potomac (James Dudley Morgan, January 12, 1903)

Historic Furnishings Report/HFC: Fort Washington Park, National Capital Parks-East (David H. Wallace, 1986)

Historic Structure Report, Administrative and Architectural Data Sections, Main Fort/Ravelin, Fort Washington, Maryland (Robert L. Carper, March 1982)

Interpretive Prospectus, Fort Washington Park (1978)

Junior Ranger Booklet, Fort Washington Park (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

Masonry Forts of the National Park Service: Special History Study (F. Ross Holland, Jr. and Russell Jones, August 1973)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Forms

Fort Washington (Marilyn Nickels and Al Korzan, September 20, 1985)

The History and Construction of Fort Washington From the Time of Its Erection Until 1884, Fort Washington, Maryland (A. Walter Jacobson, January 13, 1933)

fowa/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025