|

Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site Massachusetts |

|

NPS photo | |

Perhaps more than any other person, Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903) affected the way America looks. He is best known as the creator of major urban parks, but across the nation, from the green spaces that help define our towns and cities, to suburban life, to protected wilderness areas, he left the imprint of his fertile mind and boundless energy. Out of his deep love for the land and his social commitment he fathered the profession of landscape architecture in America.

Olmsted's unique contributions stemmed in part from the conjunction of strongly felt personal values and the needs of a young nation. America was experiencing unprecedented growth in the mid-19th century, making the transition from a rural people to a complex urban society. City life became more stressful as the crowds grew, the pace quickened, and the countryside was pushed into the distance. Olmsted and others saw the need for preserving green and open spaces where people could escape city pressures, places that nourished body and spirit. His intuitive understanding of the historical changes he was living through and his rare combination of idealism, artistry, intelligence, and practical knowledge enabled him to help soften the shocks of industrialization. Unable to separate his love and respect for the land from his belief in democracy, Olmsted saw parks as bastions of the democratic ideals of community and equality. He confronted a period of rapid mechanization and unabashed materialism with a natural sensibility and the old Jeffersonian virtues of restraint and rural simplicity, values still represented in his parks.

Olmsted was a true Renaissance Man whose many interests and ceaseless flow of ideas led him into experimental farming, writing and publishing, public health administration, preservation, and urban and regional planning. With other reformers, he pushed for protection of the Yosemite Valley. His 1864 report on the park was the first systematic justification for public protection of natural areas, emphasizing the duty of a democratic society to ensure that the "body of the people" have access to natural beauty.

In what he created and what he preserved for the future, Olmsted's legacy is incalculable. The informal natural setting he made popular characterizes the American landscape. Beyond the dozens of city and state parks enjoyed by millions of people, Olmsted and his firm set the standard for hospital and institutional grounds, campuses, zoos, railway stations, parkways, private estates, and residential subdivisions across the country. Olmsted's principles of democratic expansion and public access still guide and inspire urban planners. From the broadest concepts to the smallest details of his profession, the sign of Olmsted's hand is everywhere in our lives.

The Olmsted Park

Before Central Park and Brooklyn's Prospect Park, no large public space designed solely for recreation existed in any American city. Olmsted and his partner, the architect Calvert Vaux, had to virtually invent the American park. A pastoral-minded visionary comfortable working with hard urban realities, Olmsted was ideally suited to the task. His mastery of the technological, economic, esthetic, social, and political implications of each park gave it an enduring place in the life of the city.

REFORMER

Like many reformers, Olmsted believed he knew what was best for people.

His principles were embodied in his parks, where he translated

"democracy into trees and dirt." Every park Olmsted designed was part of

a larger social vision; his opposition to the expansion of slavery and

his advocacy of parks sprang from the same commitment to democratic

ideals. While he loved cities, he also knew them as places where people

"look closely upon one another without sympathy" and as quarters of

crime and misery. Taking Birkinhead Park in England as his inspiration,

Olmsted believed parks would replace "debasing pursuits and brutalizing

pleasure" with "rational enjoyment." Beyond its physically restorative

powers, beautiful scenery had for Olmsted a moral influence on human

behavior, promoting "communitiveness" and a healthy participation in

civic life. For him the common good was an article of faith, made

visible in his parks.

ENGINEER

The size and beauty of Olmsted's work make us sometimes forget that his

parks are artifacts. They were massive public works constructed on a

scale calling for the direction of a confident man: Swamps were drained,

thousands of tons of rock blasted and earth excavated, hills and valleys

created, water systems installed, road networks with bridges and

overpasses built, and thousands of shrubs and trees planted. Olmsted was

also a shrewd and respected administrator. He frequently encountered

hostile politicians and at Central Park won the trust of thousands of

sometimes unruly workers. One of Olmsted's most remarkable talents was

his ability to combine the practical and the beautiful. When he reshaped

a piece of land to control flooding, he also transformed it into a

pastoral landscape.

ARTIST

Olmsted saw a well-made park as a "work of art . . . framed upon a

single, noble motive." Like a sculptor freeing the form within a rough

piece of marble, Olmsted worked with earth, water, greenery, light, and

stone to set in motion a transformation that would not be fully realized

for decades. He insisted his parks were not works of self-expression;

they were designed to elicit a specific response in others. Olmsted's

design was rooted in 18th-century English landscape gardening, which had

broken with the highly formal European style. The Pastoral (finished and

"beautiful") and Picturesque (irregular and "wild") schools were subtly

married in Olmsted's own work. He respected the "genius of the place"

rooted in the immense time taken to create its forms, and he strove to

make his compositions as spontaneous and inevitable as the natural

landscape. His most original contribution was the "kinetic" nature of

his designs. The park experience is sequential and cumulative, the

visitor encountering "passages of scenery" enhanced by memory and

anticipation.

"What artist so noble . . . as he who, with far-reaching conception of beauty and designing power, sketches the outlines, writes the colors, and directs the shadows of a picture so great that Nature shall be employed on it for generations, before the work he has arranged for her shall realize his intentions."

—Frederick Law Olmsted

Building a Profession

What Olmsted called his "vagabondish and somewhat poetical" early years prepared him for his life's work. On trips through the New England countryside, he absorbed his father's reverence for "great simple country." After less than a year of college, Olmsted embarked on his "voyages of discovery": apprenticeship to an engineer, time behind a counter as a clerk and before the mast as a seaman, four years as a "scientific farmer." A published account of his 1850 walking tour of Europe, where he studied parks and estate grounds, led to an assignment for the New York Times to report the effects of slavery on the South's economy. Out of that trip came his influential book, Journey in the Seaboard Slave States (1856). In 1857, when a superintendent was needed to oversee construction of Central Park, Olmsted's literary contacts and farm experience won him the job. He and architect Calvert Vaux transformed 840 acres of rock, swamp, scattered vegetable gardens, and hog farms into a multi-faceted pleasure ground. Central Park focused international attention on what Vaux called "landscape architecture." Olmsted was preeminent in the profession for 40 years, gaining commissions for great projects like the Chicago World's Fair, the U.S. Capitol grounds, and George Vanderbilt's huge North Carolina estate. Biltmore.

The Brookline Years

Olmsted and Sons

In 1883, Olmsted moved his home and office from New York to a farmhouse in the Boston suburb of Brookline. Here he established the world's first full-scale professional practice of landscape architecture. Olmsted's personal office became the nucleus of a rambling complex constructed between 1889 and 1925. All the processes of landscape design, from drafting to printing, were carried out here.

Often preoccupied and overworked, Olmsted was nevertheless responsive to the needs of his staff and eager to provide opportunities for training. Following the lead of his friend and collaborator, architect Henry Hobson Richardson, Olmsted instituted an apprentice system that combined instruction, assigned reading, and practical experience. Two of his most important pupils were his sons, John Charles (1852-1920) and Frederick, Jr. (1870-1957). Both were trained from an early age to be landscape architects and given a more thorough grounding than their father's own haphazard education. With his managerial abilities, John Charles gave continuity to the firm after Olmsted retired in 1895 and Frederick, Jr. became a partner.

The Olmsted firm prepared design plans for an estimated 44 states, the District of Columbia, and Canada. In 1980, the National Park Service acquired the site and began to inventory and conserve the historic design records, including thousands of plans and photographs dating from 1860 to 1980. Olmsted National Historic Site transcends the traditional role of a museum by serving as a center for the study and preservation of landscapes. The Olmsted Archives assists researchers from across the nation. The Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation shares technical expertise in historic landscape preservation and maintenance.

"A grand parkway of picturesque type . . . reaching from the heart of the city into the rural scenery of the suburbs."

—Frederick Law Olmsted

The Emerald Necklace

Among the more impressive documents in the Olmsted archives is the plan for the Boston Park System. It illustrates one of the boldest and most complex undertakings of Olmsted's career and is perhaps his most influential design. His increasing involvement in the project from its inception in the mid-1870s was a major factor in Olmsted's decision to move from New York to Boston. Completed near the end of the century, the 5-mile "emerald necklace" of linked parks, ponds, and parkways was a brilliant combination of comprehensive planning, technical engineering, and imaginative design.

Olmsted spent much of his career working out the interdependent relationship he felt should exist between city and country. Many of his finest principles of urban planning were realized in the Boston Park System. A variety of landscapes were woven into the fabric of the city, from the salt water marshes of the Back Bay Fens to the sheep meadows of Franklin Park. Olmsted anticipated many different uses for parkland, including in this greenbelt both large and small spaces, intimate glades along riverbanks, dense wilderness, open water, and a convenient system of trails and drives.

His vision for the landscape is best expressed in an 1881 report to the Boston Park Commission. The Back Bay Fens was a sewage-fouled tidal creek and swamp that periodically flooded. Olmsted's plan simultaneously solved the drainage and health problems and turned the surrounding area into "scenery of a winding, brackish creek, within wooded banks; gaining interest from the meandering course of the water." Muddy River would be "a fresh-water course bordered by passages of rushy meadow . . . trees in groups, diversified by thickets and open glades." The largest body of water in the system, Jamaica Pond, formed a "natural sheet of water... shaded by a fine natural forest growth . . . darkening the water's edge and favoring great beauty in reflections and flickering half-lights." The Arboretum offered "Eminences commanding distant prospects, in one direction seaward over the city, in the other across . . . to blue distant hills." Visitors could seek a "Complete escape from town" in Franklin Park. Olmsted envisioned a "lovely dale gently winding between low wooded slopes, giving a broad expanse of unbroken turf, lost in the distance." It all formed "a grand parkway of picturesque type . . . reaching from the heart of the city into the rural scenery of the suburbs." The practical and popular success of Olmsted's work in Boston has inspired similar city and regional planning efforts across the country.

Visitors to the National Historic Site are only minutes away from the Boston Park System. While the essence of his plans remain intact, some of Olmsted's finest parks have suffered a variety of insults and injuries over the years. Highways and parking lots interrupt scenic compositions and unique green passages. Recreational interests stress fragile landscapes, altering historic features and the personality of Olmsted's parks. High costs often discourage necessary maintenance and restoration. Yet in Boston and elsewhere, the Olmsted landscape survives despite all odds, a fundamental component of the city's character and testament to the strength of Olmsted's enduring vision.

The Suburban Dream

Olmsted was a prophet of suburbia, believing that "no great town can long exist without great suburbs." During the course of his career, he designed more than a dozen suburban communities outside cities like Baltimore and Chicago. They were intended to be places where people could express their individuality and practice the art of gardening while retaining convenient access to the commerce and amenities of the city. As in his public parks, Olmsted's ideals were reflected in his vision of the private landscape, which fosters delicacy of perception and of sentiment, strengthens family ties and feeds the roots of patriotism.

In moving to the garden suburb of Brookline, Olmsted showed confidence in what he believed to be the city form of the future. His own home grounds were carefully landscaped to illustrate how the ideal suburban lifestyle might be achieved. Many of the same design principles for which Olmsted was famous at a larger scale were applied with equal success on the small estate he named Fairsted.

Elements of the picturesque and pastoral styles of landscaping so popular in Olmsted-designed parks are likewise featured on the Fairsted grounds. Barriers of earth and plantings used by Olmsted along park borders to isolate visitors from the city are found at his home in the form of massed trees and shrubs. The viewer's attention is directed to a stately American elm on the center lawn.

Though spectacular, this tree does not interfere with appreciation of the landscape as a whole, in keeping with Olmsted's preference for simple rather than "strange or striking" landscape elements.

Praising Olmsted's landscape for the 1893 Chicago World's Fair, a newspaper of the period recognized the common principles that informed all of his work from the grand public statement to the private dwelling space: "[Olmsted's] home is as beautiful, as thoroughly in accord with all of nature's happiest little dreams . . . as the great park in the center of the Nation's metropolis, to which Mr. Olmsted gave the first great result of his keen susceptibility to the power of nature's best possibilities. Any one who rambles through the leaf-strewn walks and climbs along some rock[y], wooded path of Central Park today can safely imagine just such charming bits of scenery about the home of the man whose guiding genius made Central Park as it is, possible..."

Olmsted proposed that every suburban home should have "attractive open-air apartments" like the conservatory he added to his 1810 farmhouse. This glassed-in space eases access to "nature's best possibilities" by allowing intimate views of the domestic scenery that Olmsted created with such care. Uppermost in his mind was the idea that body and spirit could be healed through close association with nature, a benefit he wanted all to enjoy.

The most celebrated Olmsted suburb was Riverside (1869), near Chicago. Connected by rail to the city, the 1600 acres of rolling hills bordering the Des Plaines River was ideal for Olmsted and Vaux's first experiment in community planning. The result was a harmonious integration of man and landscape. Rejecting the grid, he used sunken roads, accommodating them to natural contours and obstacles. Irregular clusters of trees created a spontaneous rural atmosphere. Olmsted protected the river and made it the focus of the community by devoting 700 acres to common parkland along the banks. Riverside remains today a model suburb and an example of what can be achieved with imagination and careful planning.

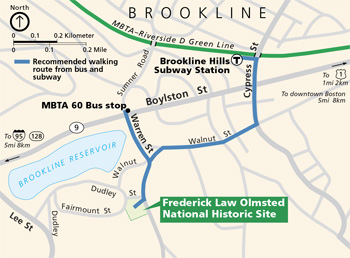

(click for larger map) |

About Your Visit

Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site is open Friday, Saturday, and Sunday from 10 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Groups are welcome at other times by advance reservation. Publications about landscape design history can be purchased at the bookstore. Contact: Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site; www.nps.gov/frla.

For Your Safety

Use caution while touring the multi-level rooms and stairways of the

house and office complex. Comfortable dress is recommended for viewing

the outside grounds. Only a small number of vehicles can be accommodated

in the visitor parking area, and street parking may be necessary. Watch

for traffic on neighborhood roadways. Have a safe and enjoyable

visit.

Accessibility

Limited parking is available to visitors who are disabled. Ramp access

into and within the first floor house museum is available. Multi-level

rooms in the first and second floor historic office may be difficult for

some to maneuver.

Source: NPS Brochure (2000)

|

Establishment Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site — October 12, 1979 |

For More Information Please Visit The  OFFICIAL NPS WEBSITE |

Documents

Cultural Landscape Report for the Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site — Volume II: Existing Conditions, Analysis and Treatment (Lauren G. Meier, 1994, printed 2017)

Cultural Landscape Report for the Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site — Volume III: Record of Treatment (Devon King, James Mealey, Mona McKindley, Aaron Erzinger, Lauren G. Meier and Eliot Foulds 2022)

Cultural Landscape Report for the Green Hill Parcel, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site, Brookline, Massachusetts (Christopher Beagan, 2017)

Fairsted: A Cultural Landscape Report for Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site — Volume I: Site History Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation Publication #12 (Cynthia Zaitzevsky, 1997)

Fairsted: Home and Office of Frederick Law Olmsted, Vol. 1: The House (Marie L. Carden and Andrea M. Gilmore, 1998)

Fairsted: Home and Office of Frederick Law Olmsted, Vol. 2, Part 1: The Offices (Andrea M. Gilmore, 1987)

Fairsted: Home and Office of Frederick Law Olmsted, Vol. 2, Part 2: The Offices (Andrea M. Gilmore, 1987)

Fairsted: Home and Office of Frederick Law Olmsted, Vol. 3: The Barn, Shed and Fences (Marie L. Carden and Andrea M. Gilmore, 1990)

Feasibility/Suitability Study, Frederick Law Olmsted Home and Office as a Unit of the National Park Service (June 1979, rev. May 1979)

Foundation Document, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site, Massachusetts (November 2016)

Foundation Document Overview, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site, Massachusetts (January 2016)

Frederick Law Olmsted, Landscape Architect, 1822-1903 (Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. and Theodora Kimball, eds., 1922)

Grounds Maintenance Manual: Longfellow and Frederick Law Olmsted Historic Sites (Rudy J. Favretti, 1987)

Historic Furnishings Report: The Olmsted House "Fairste" and Office, Volume 4: Implementation Plan for Portion of Olmsted Landscape Architecture Office, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site (Hardy-Heck-Moore, Inc. and Volz & Associates, Inc., March 2011)

Historic Grounds Report and Management Plan, Frederick Law Olmsted (Lucinda Adele Whitehill, 1982)

Historic Resource Study: The Olmsteds and the National Park Service (Rolf Diamont, Ethan Carr and Lauren Meier, 2020)

Junior Ranger Activity Book, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site (Date Unknown; for reference purposes only)

National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form

Frederick Law Olmsted House (Patricia Heintzelman, October 10, 1975)

Newsletter: Fall 2003

The Olmsted National Historic Site and the Growth of Historic Landscape Preservation 1979-2004 (©David Grayson Allen, 2005)

Visual Information System, Frederick Law Olmsted National Historic Site (Date Unknown)

Justin Martin: 'Genius of Place: the Life of Frederick Law Olmsted'

frla/index.htm

Last Updated: 01-Jan-2025